Intersecting with Eternity

歷史的垃圾時間

This chapter in Intersection with Eternity is paired with MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election, part of our series Spectres & Souls, our account of the Danse Macabre between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China (for more on this on-going gyration, see the Epilogue to China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season). Published on the eve of the final day of voting in the 60th quadrennial presidential election of the United States, the double theme of this chapter is ‘waiting for the barbarians’ and ‘the garbage time of history’.

***

The expression ‘intersecting with eternity’ is inspired by a passage in Mary Norris’s excursions into the world of Ancient Greece:

… the real world of crabby landladies and deceptive road signs would crack open and mythology would spill out. You have to pay the rent in the real world, but it’s crazy not to embrace those moments when it intersects with eternity.

— Mary Norris, Greek to Me: adventures of a comma queen, 2019

Intersecting with Eternity is a mini-anthology of literary and artistic works, both past and present, that are part of the unbroken stream of human awareness and poetic self-reflection, Intersecting with Eternity is a companion to The Tower of Reading and an extension of The Other China section of China Heritage.

***

For the United States of America, the year 2024 is significant both for the United States and for China. Two years shy of the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, the 2024 presidential race recalled the promise of that rebellion against the British throne and the threat of a new tyranny. In China, 2024 marked the 380th anniversary of the collapse of the Ming dynasty in 1644, an event of immense consequence for modern China and one from which Communist leaders like Mao, Jiang Zemin and Xi Jinping drew lessons for their own rule.

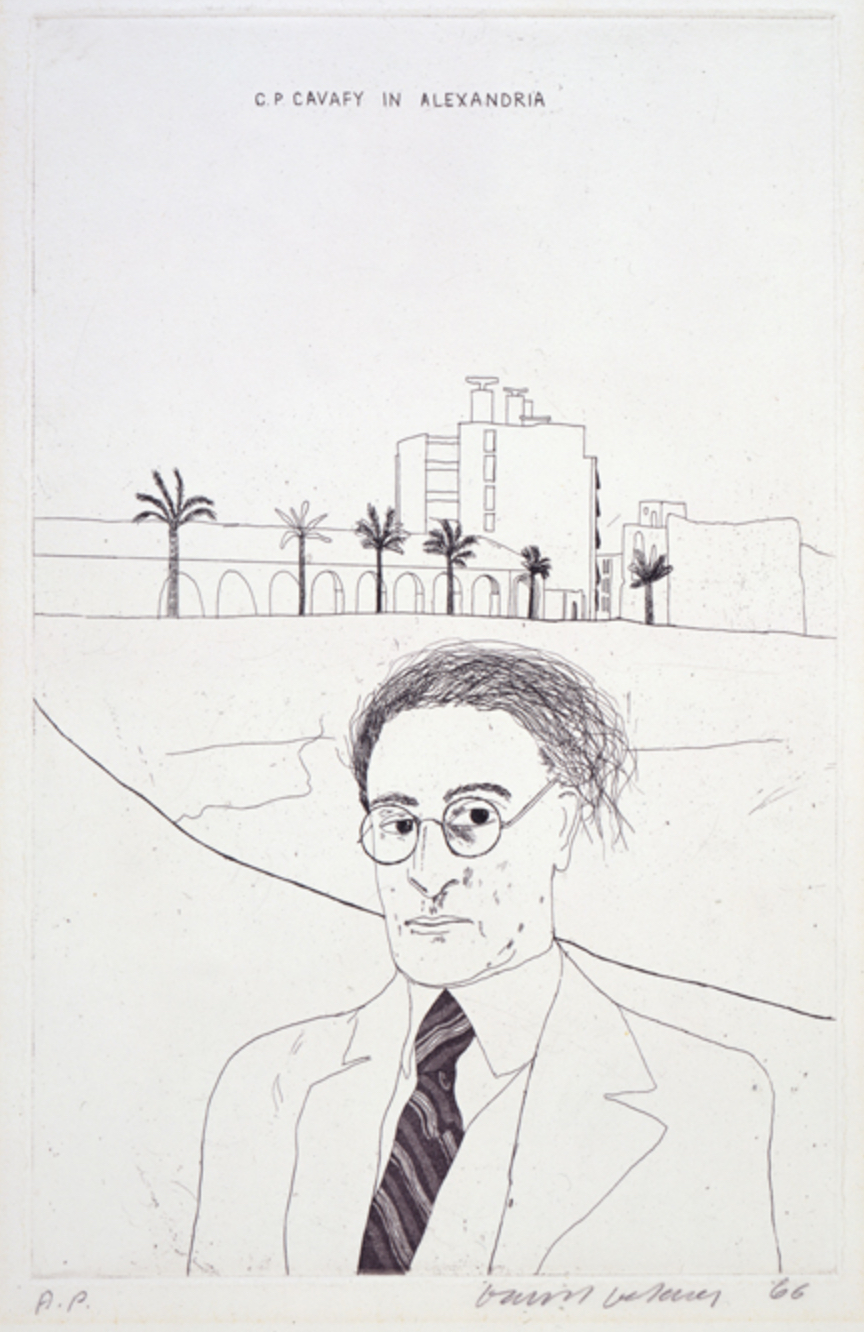

‘Waiting for the Barbarians’, a well-known poem by Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933), and interpretations of that text — by Laurie Anderson and Daniel Mendelsohn — allow us to explore the existential anxieties of the present age. We extend our discussion with a note on ‘the garbage time of history’, a topic of recent significance in Chinese debates about the present and the future.

It is unclear, however, who will end up in the metaphorical ‘ash heap / garbage pile of history’ 歷史的垃圾堆 (or, ‘the dust heap of history’, as Trotsky put it when dismissing his enemies in 1917). Twenty-five years ago I observed that in the Sino-American clash both sides presumed that the other would be relegated to the trash heap (see Conflicting Caricatures), just as for decades America’s corporatised political duopoly has struggled to marginalise the other side. So, in conclusion, we offer an image of some of today’s ‘barbarians at the gate’ and end with the tag-line ‘No Dumping Garbage’ 禁止倒垃圾. This is both to note that the word ‘garbage’ was bandied about with absurd flourish during the last week of the US presidential race and to acknowledge that we are all living on the edge, in a garbage time of history.

***

‘Cultural exhaustion, political inertia, the perverse yearning for some violent crisis that might break the deadlock and reinvigorate the state: these themes, so familiar to us right now, were favorites of Cavafy,’ notes Daniel Mendelsohn below. These same themes also run through contemporary Chinese discourse (see The Threnody of Tedium). Cavafy’s poem ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ addresses history on the edge today just as it will continue to resonate with readers in long distant unsettled times.

As Laurie Anderson says in her incantation-like reading of Cavafy’s poem:

there are no barbarians anymore

those people were a kind of solution

unless we

ourselves

unless we ourselves

are The

Barbarians

unless we

ourselves

are The

Barbarians …

Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

4 November 2024

***

See also:

America’s Empire of Tedium — Contra Trump 2024

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

***

Further Reading:

- 迴 The Tyranny of Chinese History

- 旋 The Lugubrious Merry-go-round of Chinese Politics

- Chinese Time, Part I: 新鬼舊夢— More New Ghosts, Same Old Dreams; and, Part II: 忘卻的紀念 — the struggle of memory against forgetfulness

- The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949

- Mark Liberman, The what of history?, Language Log, 23 December 2011

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

Waiting for the Barbarians

Constantine Cavafy

—What is it that we are waiting for, gathered in the square?

The barbarians are supposed to arrive today.

—Why is there such great idleness inside Senate house?

Why are the Senators sitting there, not passing any laws?

Because the barbarians will arrive today.

Why should the Senators still be making laws?

The barbarians, when they come, will legislate.

—Why is it that our Emperor awoke so early today,

and has taken his position at the greatest of the city’s gates

sitting on his throne, in solemn state, and wearing the crown?

Because the barbarians will arrive today.

And the emperor is waiting to receive

their leader. Indeed he is prepared

to present him with a parchment scroll. In it

he’s conferred on him many titles and honorifics.

—Why is it that our consuls and our praetors have come out today

wearing their scarlet togas with their rich embroidery,

why have they donned their armlets with all their amethysts,

and rings with their magnificent, glistening emeralds;

why is it that they’re carrying such precious staves today,

maces chased exquisitely with silver and with gold?

Because the barbarians will arrive today;

and things like that bedazzle the barbarians.

—Why do our worthy orators not come today as usual

to deliver their addresses, each to say his piece?

Because the barbarians will arrive today;

and they’re bored by eloquence and public speaking.

—Why is it that such uneasiness has seized us all at once,

and such confusion? (How serious the faces have become.)

Why is it that the streets and squares are emptying so quickly,

and everyone’s returning home in such deep contemplation?

Because night has fallen and the barbarians haven’t come.

And some people have arrived from the borderlands,

and said there are no barbarians any more.

And now what’s to become of us without barbarians.

Those people were a solution of a sort.

— translated by Daniel Mendelsohn

Daniel Mendelsohn is a prolific author and translator. “The Elusive Embrace” a translation of the complete works of C. P. Cavafy; and a study of Greek tragedy. He teaches at Bard College.

Mendelsohn’s books include a two-volume translation of the poetry of C. P. Cavafy (2009), An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic (2017), three collections of essays and Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate (2020). His new translation of the Odyssey will be published by the University of Chicago Press in April 2025.

Laurie Anderson’s Interpretation of Cavafy

(‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ and ‘Ithaka’)

Mendelsohn on Cavafy — one

“Waiting for the Barbarians” begins with a CinemaScope spectacle of imminent national decline. In an enormous square in an unnamed city (Rome? Constantinople? It doesn’t matter, because it keeps happening everywhere, after all), a throng has gathered in anxious expectation of the arrival of some (also unnamed) “barbarians.” The government, as those opening lines make clear, has ground to a halt—not least because the most powerful men in the land, starting with the head of state himself, the emperor (who has “taken his position at the greatest of the city’s gates / seated on his throne”) and including his toga-wearing, jewel-encrusted officials, are also milling around waiting for the barbarians. (Cavafy cannily opens the poem with the image of the stilled Senate house and idle legislators in order to pique our curiosity; only after does he pan to the bustling plaza whither the action—or rather, anticipation—has shifted.)

There is a vaguely sinister suggestion that some kind of appeasement is on the menu: we’re told that the emperor is prepared to present a “parchment scroll” that will confer “many titles and honorifics” on the barbarian leader—not, you strongly suspect, that the brutish foreigner will care; clearly the barbarians are in a position to take what they want. This may be why the only group not represented in the welcoming delegation are wordsmiths: the “worthy orators” who would normally “deliver their addresses, each to say his piece” at such a major occasion. We sense that things have moved past the stage of discussion or debate—even staged discussion and debate. Anyway, as Cavafy observes, barbarians “are bored by eloquence and public speaking.” In the ensuing silence, we notice only the disturbing images that precede the poem’s famously surprising ending: the faces of the crowd, suddenly serious, the streets emptying, the citizens shambling home “deep in contemplation.”

Why is the square suddenly emptying out, the crowd dispersing? “Because night has fallen and the barbarians haven’t come.” It’s only in the last two lines that the poet springs his unexpected finale: that the crowd was, in fact, waiting eagerly for the barbarians (“what’s to become of us without barbarians?”)—and, in fact, “those people were a solution of a sort.”

Cultural exhaustion, political inertia, the perverse yearning for some violent crisis that might break the deadlock and reinvigorate the state: these themes, so familiar to us right now, were favorites of Cavafy. He was, after all, a citizen of Alexandria, a city that had been an emblem of cultural supremacy—founded by Alexander the Great, seat of the Ptolemies, the literary and intellectual center of the Mediterranean for centuries—and which had devolved to irrelevancy by the time he was born, in 1863. When you’ve seen that much history spool by, that much glory and that much decline, you have very few expectations of history—which is to say, of human nature and political will. In poem after poem, in verses that take both ancient myth and ancient history as their subjects, the poet charted the inevitable failure of our best efforts. These lines from “Trojans” (the reference is to the “Iliad”) written in 1900, are typical: We imagine that with resolve and daring

we will reverse the animosity of fortune,

and so we take our stand outside, to fight.But whenever the crucial moment comes,

our boldness and our daring disappear;

our spirit is shattered, comes unstrung;

and we scramble all around the walls,

seeking in our flight to save ourselves.

The grandiose promise, the sordid reality: this, for Cavafy, was the inevitable cycle of human affairs. What’s interesting and distinctive about this poet is that he doesn’t necessarily sit in judgment. This is simply the way people are. …

Inaction, of course, can be as destructive as ill-advised action. This is why the aimless standing around and waiting that Cavafy so brilliantly evokes in “Waiting for the Barbarians” is so contemptible. The vigor of the leaders, the effectiveness of their oratory, the political will of the citizens have been so atrophied by indolence and luxury and complacency that they can only hope for disaster as a means of renewing the state. Depending on your politics, you may be tempted to map the current political crisis onto “Waiting for the Barbarians” in any number of ways: Are the barbarians the Democrats or the Republicans? Is the “emperor” Obama or Boehner—or Reid? To Cavafy, those details would have been of little interest. The point was that these things happen again and again, and that whatever else they may mean, they are always, always tests of character—for individual politicians and for whole nations. It is even—or rather, especially—when the barbarians (whoever they are) are at the gates, when crisis is inevitable or even imminent, that right action is the only option, whether or not it’s likely to succeed. Even in politics, it’s the journey that counts, not just the destination.

— “Waiting for the Barbarians” and the Government Shutdown, The New Yorker, 1 October 2013

***

Mendelsohn on Cavafy — two

In Constantine Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians,” the representatives of a very grand and sophisticated culture, unnamed but apparently Rome, assemble at the city gate in great state, from the emperor to his various officials, awaiting the arrival of envoys from the (also unnamed) “barbarians.” The city has fallen into an anticipatory stupor: the senators sit around making no laws, and the orators fall silent, having tactfully absented themselves. (The barbarians are “bored by eloquence and public speaking.”) They all wait from early morning until evening, fidgeting with their embroidered scarlet togas, their amethysts and emeralds, until it becomes clear that the barbarians aren’t going to come. Only in the final line of the poem does Cavafy give the proceedings an unexpected twist: the emperor and the rest, you learn, are actually looking forward to the barbarians’ arrival. “Perhaps these people,” the narrator sighs in the last line, “were a solution of a sort.”

So the poem is about confounded expectations in more ways than one. There’s the disappointed anticipation of the waiting emperor and his people, of course, but even more, perhaps, there are the oddly thwarted expectations of the reader of the poem, which have been set up by that sonorous, portentous, and now-famous title. Detached from its context, the phrase “waiting for the barbarians,” which has been used as everything from the title of a novel by J. M. Coetzee to the name of a chic men’s clothing store in Paris, seems to be about the plight of a precious civilization perilously under siege by the crude forces of barbarity. And yet Cavafy himself clearly saw it differently. A note he wrote in 1904, the year he published the poem, indicates that for him it was “not at all opposed to my optimistic notion”—that it represented, indeed, “an episode in the progress toward the good.”

Why, you wonder, should the imminent advent of the barbarians suggest positive progress? Here it’s important to remember a bit of biography. Cavafy had come of age in the late nineteenth century, the era of the flowery and highly perfumed Decadents, and only when he was around forty—the time he wrote “Waiting for the Barbarians”—did he set about stripping his work of all derivative artifice, transforming himself into an idiosyncratic modernist. So the poem may well be a parable about artistic growth—the unexpectedly complex and even, potentially, fruitful interaction between old cultures and new, between (we might say) high and low; about the way that what’s established and classic is always being refreshed by new energies that, at the time they make themselves felt, probably seem barbaric to some. As Cavafy knew well—he was, after all, a specialist in the marginal moments of ancient history, the era in which Greece yielded to Rome, when paganism met Christianity, when antiquity made its long and gentle slide into the early Middle Ages—there rarely are any real “barbarians.” What others might see as declines and falls look, when seen from the bird’s-eye vantage point of history, more like shifts, adaptations, reorganizations.

— from the Foreword to Daniel Mendelsohn, Waiting for the Barbarians, New York: New York Review of Books, 2012

Daniel Mendelsohn Discusses C.P. Cavafy

— Onassis Foundation, 21 January 2014

[See also The Critic’s Voice: Daniel Mendelsohn on Cavafy, 92Y Readings, 6 June 2012]

Archive of Desire

— a festival inspired by the poet C.P. Cavafy

— Onassis Foundation, 5 February 2023

China’s Garbage Time of History

歷史的垃圾時間

Alexander Boyd

When the result of a sporting match becomes a foregone conclusion and lesser players are subbed in to run out the clock, announcers often term it “garbage time.” The latest term to sweep the Chinese internet holds that nations, too, experience a similar phenomenon: the “garbage time of history” (历史的垃圾时间, lìshǐ de lājī shíjiān). Coined by the essayist Hu Wenhui in a 2023 WeChat post, “the garbage time of history” refers to the period when a nation or system is no longer viable—when it has ceased to progress, but has not yet collapsed. Hu defined it as the point at which “the die is cast and defeat is inevitable. Any attempt to struggle against it is futile.” Hu’s sweeping essay led with Soviet stagnation under Brezhnev and then jumped nimbly between the historiography of the collapse of the Ming Dynasty and Lu Xun’s opinions on Tang Dynasty poetry. Unasserted but implied in the essay is that China today finds itself in similar straits. CDT has translated a small portion of the essay to illustrate its main points:

During Brezhnev’s nearly 20 years in power (1964-1982), the New Russian Empire lashed out in all directions, and even seemed capable of taking down mighty Uncle Sam. Today, with the advantage of hindsight, it is easy to recognize that [the Soviet] colossus had feet of clay, and was a hollow shell riven with internal difficulties. The 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, in particular, plunged the empire into a quagmire. It would be fair to say that the 1989 fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union both began in 1979.

I am willing to state unequivocally that the “garbage time” of the Soviet Union began in 1979. Gorbachev only hastened the end of that garbage era.

[…] In [Chinese-American historian] Ray Huang’s opinion, the history of the Ming Dynasty came to an end in 1587, during the fifteenth year of the Wanli Emperor’s reign. The subtext of Huang’s “macro-historical” viewpoint is that that was the year in which all of Chinese history came to an end, as well. The rest, including the remaining three hundred years of the Qing Dynasty, had lost any historical “significance” and were nothing more than a “garbage time” in history.

[…] In history, as in all competitive sports, there will always be some garbage time. When that time comes, the die is cast and defeat is inevitable. Any attempt to struggle against it is futile, and the best you can hope for is to reach the end with as much dignity as possible. [Chinese]

The Chinese state has struck back against use of the term “garbage time.” The East is Read, a Substack blog run by the Chinese think tank the Center for China and Globalization, translated three essays rebutting the term. The first, by a former Xinhua journalist, attacked the phrase as a product of “literary youth” who “idolize bourgeois ‘universal values’ and fantasize about transplanting these values and even political systems to China.” The second, published by a prominent academic in Beijing, argued that the world is undergoing “structural subversions and epochal surpassings between the East and the West in commodities, currency, brands, information, knowledge, systems, and even race and ideology” that should not be “tarnished and distorted” by the phrase. The last, published by the official newspaper of Beijing’s municipal Party committee, held that the term is a “logical fallacy” and attacked those who would “lie flat” before the “dawn of victory.”

Some analysts, both Western and Chinese, hold that the phrase refers primarily to economic anxiety, thus placing it in the same tradition as “Kong Yiji literature” and the viral portmanteau “humineral.” Bloomberg framed it as an expression of “rising public discontent over President Xi Jinping’s economic agenda.” State media has made a similar categorization. An essay originally published to The Intersect (交汇点, jiāohuìdiǎn), a mobile news outlet controlled by Jiangsu’s provincial Party committee, argued that efforts to characterize China as being in “garbage time” are disingenuous and false, and specifically cited a sudden influx of foreign travel bloggers who have sung the nation’s praises:

Over the years, Western countries have waged continuous “cognitive warfare” against China. Western media narratives about China have swung between “peak China,” “overcapacity,” “threat to the global order,” and “on the brink of collapse.” These views are inherently contradictory, and not one of them has yet come to pass. Why is that? Because the real China does not exist in some “separate universe.” This year, “China travel” has become a viral global trend. Foreign tourists are flocking to China to experience its beautiful scenery, bustling streets, and modern conveniences. These foreign tourists, who rave about China with cries of “So city!,” would never think of it as a place mired in the garbage time of history. In today’s China, there are so many stories [that encapsulate China’s economic development] like “moon mining,” and “raising fish in space.” Anyone who drones on about “garbage theory” while fixating solely on the growing pains of a developing economy in transition has made their ill intentions abundantly clear. [Chinese]

Online, the phrase has become a meme to express economic anxiety. (Of course, overt expressions of political dissent are often heavily censored.) At The Guardian, Amy Hawkins reported on how Chinese Internet users have adopted of the term as a way to express bleak sentiments about the Chinese economy:

The sentiment can be summed up by a graphic, widely shared on social media – and since censored on Weibo.

Entitled the “2024 misery ranking grand slam”, it tallies up the number of misery points that a person might have earned in China this year. The first star is unemployment. For two stars, add a mortgage. For a full suite of eight stars, you’ll need the first two, plus debt, childrearing, stock trading, illness, unfinished housing a-nd, finally, hoarding Moutai, a famous brand of baijiu, a sorghum liquor.

“Some people say that history has garbage time,” wrote one Xiaohongshu user who shared the graphic, along with advice about self-care. “Individuals don’t have garbage time.”

[…] But some social media users are sanguine about being online in such an era. One Weibo blogger, who feared his account might soon be deleted because of a post he made about a recent food safety scandal, wrote a farewell to his followers. “No matter what happens, I am very happy to spend the garbage time of history with you”. [Source]

***

Source:

- Alexander Boyd, WORD OF THE WEEK: GARBAGE TIME OF HISTORY (历史的垃圾时间, LÌSHǏ DE LĀJĪ SHÍJIĀN), China Digital Times, 1 August 2024

The Barbarians

***

No Dumping Garbage