Celebrating New Sinology

辭龍迎蛇

A certain wariness surrounds the Snake, one of the twelve zoological signs of the traditional Chinese calendar, and not only because the reptile inspires fear and repulsion. The Chinese word 蛇 shé, snake, is homophonous with 折 shé, ‘to break’ or ‘lose’. Business people in particular regard the snake with some trepidation since 折本 shé běn , ‘diminished capital’, hardly chimes with the usual New Year’s benedictions to make money 發財 and enjoy good fortune 吉利.

Even greater is the anxiety that things may start out with a ‘tiger’s head only to end in a snake’s tail’ 虎頭蛇尾. People attempt to ward off maledictions by employing sayings about ‘not losing out in the Year of the Snake’ 絕不蛇本 or ‘hoping for the Golden Snake [of wealth] to come out of its hole’ 金蛇出洞.

In recent years, bureaucrats too have become increasingly alert to any ominous snakes that may shé, break or foreshorten, their ‘progress along the path to official success’ 官運 resulting in a side-tracked career or even abject failure. For this reason, the Year of the Snake, one also known as the Year of the Little Dragon 小龍年, calls for a measure of alertness and even of alarm.

***

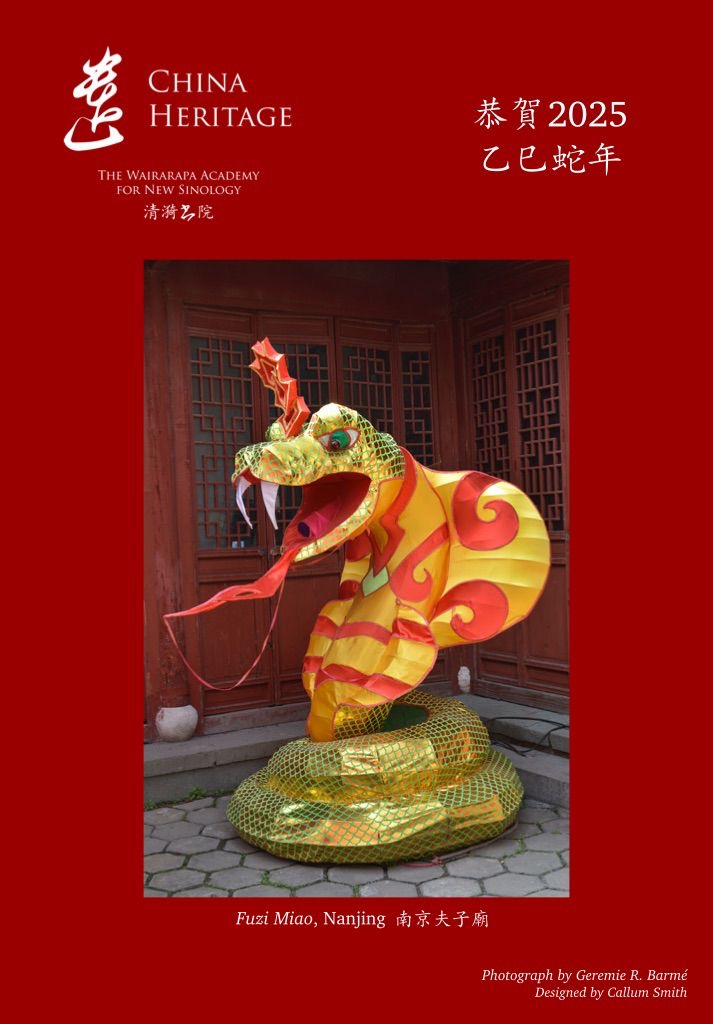

The photograph featured in this year’s China Heritage greeting card below was taken at the Confucian Temple 夫子廟 in Nanjing during a research trip that I made to that city with Lois Conner in March 2013. When we were visiting Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum the following day, I learned that Quan’r 圈兒, my girl cat, was at a veterinary hospital in Canberra recovering from an encounter with an eastern brown snake, one of the most venomous reptiles among Australia’s famously poisonous fauna. Quan’r eventually recovered and we, along with her brother, Hupiqiang 虎皮牆, were able to enjoy another happy decade together.

In late January 2024, I dedicated the advent of the Year of the Dragon to the memory of Hupiqiang 虎皮牆, who had died only a few days earlier. Now, on the eve of the Year of the Snake, I recall Quan’r’s harrowing encounter with that eastern brown in 2013. I mourn both her and Hupi still.

***

The research trip that Lois and I had made formed the basis for the first China Heritage Annual, the theme of which was Nanking. The theme of China Heritage Annual 2025 is Celebrating New Sinology.

My thanks to Callum Smith, the webmaster of China Heritage, for designing our Lunar New Year’s card and to Lois Conner for permission to use her photograph of a ‘snake shop’ in Yangshuo, Guangxi province.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 January 2025

Lunar New Year’s Eve

甲辰臘月廿九除夕

***

Spring Festival in China Heritage

- 2016: The Golden Monkey 金猴, a Year to Remember

- 2017: The Year of the Rooster, On Reading; The Year of the Rooster, On Seeing, The Year of the Rooster, On Eating, Injecting, Imbibing & Speaking

- 2018: Mondo Cane, The 2018 Year of the Dog 戊戌狗年

- 2019: The Year of the Pig Foretold; In the Year of the Pig — Chairman Mao’s Bitch and Xi Jinping’s Swine; Outside the Pigsty Looking In, Two Views

- 2020: 2019-nCoV — A Teaching Moment, Spring Term 2020

- 2021: Ox Herding & the Xinchou Year of the Ox 辛丑牛年

- 2022: Greeting the Year of the Tiger 壬寅虎年; The Tail-end of Tiger Tyranny

- 2023: Now What? — Greeting the Guimao Year of the Rabbit 癸卯兔年; A Protection Mantra for the Year of the Rabbit; Rabbiting on with Lao Shu; Lao Shu’s Farewell to the Year of the Rabbit

- 2024: An Ambitious Dragon’s Nightmare; So Starts the Spring; Embarking upon the Jiachen Year of the Dragon 甲辰龍年

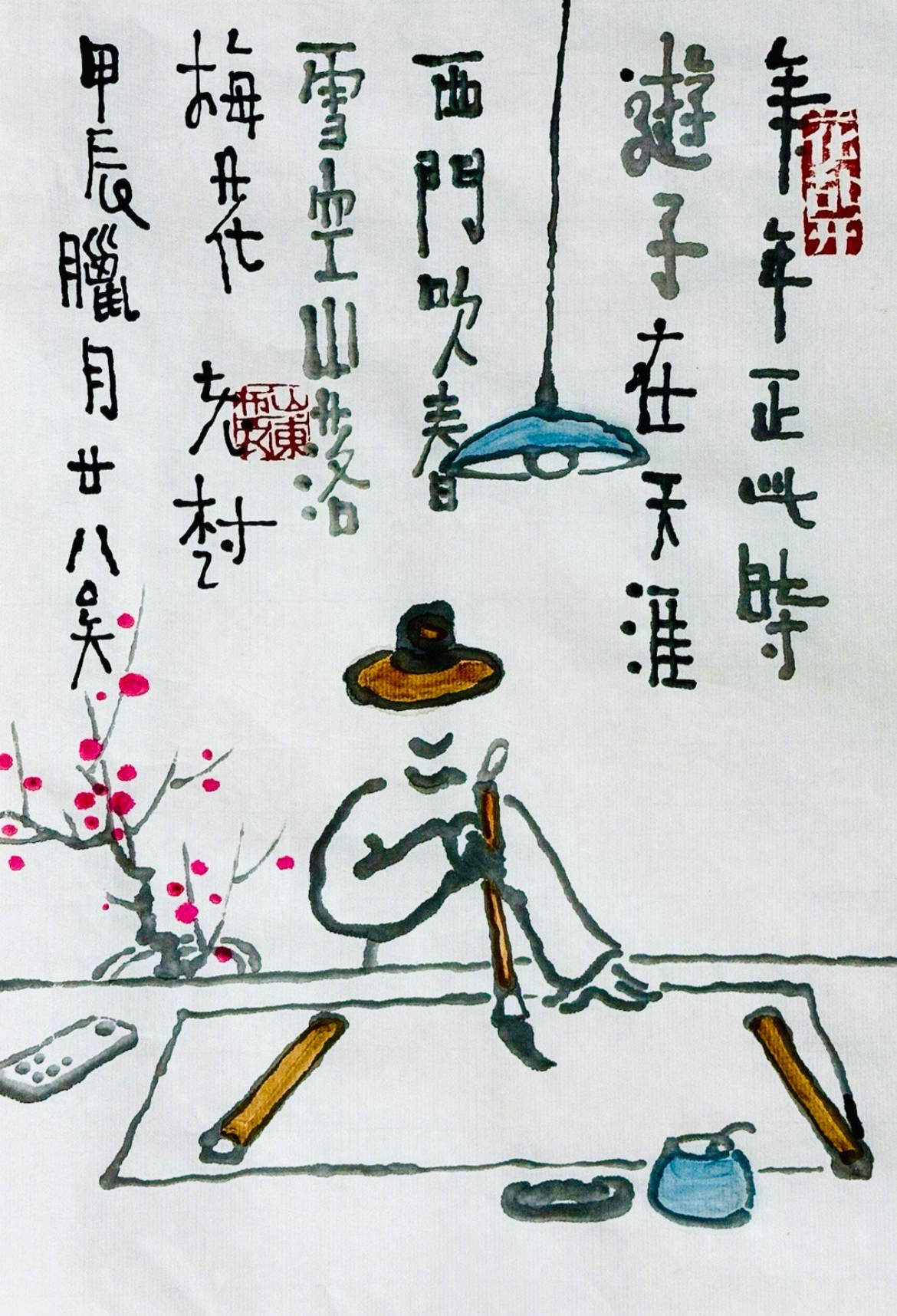

This time each year, as the traveller wanders in distant parts,

there’s a hint of spring in the fluttering snowflakes nearby

and in the rain of plum blossoms in distant hills.

— Lao Shu, Twenty-eighth Day of the

Last Month of the Year of the Dragon

(See also From Lao Shu’s Studio of Drunken Dreams, 28 January 2025.)

***

Two New Years

元旦懟春節

The Chinese calendar is cluttered with festivals, anniversaries and celebrations of various kinds. Local regions have long marked the changing seasons and customs with holidays or feast days. In the dynastic era, different festivals would flourish in importance or fade into relative, or local, obscurity. In certain epochs country-wide festivities were proclaimed.

Following the collapse of dynastic rule in 1911 and the rise of the Republic of China, traditional holidays jostled with new state-promulgated national days. Under the People’s Republic (1949-), holidays and celebrations have waxed and waned in tandem with the shifting fashions of revolutionary fervour.

For instance, those of a certain generation may well recall the decade when families were forced to enjoy (in moderation) a Revolutionised Spring Festival 革命化春節 or Chairman Mao’s Birthday (conveniently falling on the day after Christmas). Then there was the plethora of commemorations of Party meetings, announcements, rhetorical victories, heroes and martyrs. These were often marked with fireworks, clamorous processions with drums and slogans, as well as song-and-dance performances. For later generations, the mix of old (and many revived) festivities (and extended holidays) with the days on which the Party congratulates itself and its favoured causes (May First; May Fourth; Children’s Day (1 June); August First; October First, etc) is welcome for it means less work and more shopping.

— from An Ambitious Dragon’s Nightmare, 26 January 2024

***

Yuan Tengfei Discusses Spring Festival

***

In the early 20th century, successive governments sought to suppress the traditional Lunar New Year celebrations in order that the country might break from ancient customs and ”modernize” by following the example of the West. Luckily for workers today, though, the attempts failed.

In ancient China, Yuandan was already celebrated as the beginning of the first month of the year, though the actual date of this moved around according to which ruler or dynasty was in charge. The Xia dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BCE) is said to have established the first calendar based on the moon’s cycles, which is the basis of the Chinese lunisolar calendar (often just called lunar calendar) still used today. In their calendar, the Xia designated Yuandan as the first day of the first month, or Zhengyue (正月).

Later dynasties designated different months in the Xia calendar as Zhengyue: for the Shang (1600=1046 BCE) it was the 12th month, and for the Qin (221-206 BCE) it was the 10th month. However, at the start of the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), Yuandan was moved back to the first day of the first lunar month, and continued to be celebrated on that date until the fall of the Qing dynasty (1616-1911).

[Note: Here, in accord with contemporary party-state practice, the author folds the years of the Latter Jin 後金 — 1616-1636 — into the chronology of the Qing dynasty proper.]

When the Qing dynasty fell and the Republic of China emerged from the wreckage, Sun Yat-sen (孙中山), the provisional president of the new regime, declared that the country would henceforth follow the Gregorian calendar instead of the traditional lunar one. Yuandan, therefore, changed from the first day of the lunar calendar to January 1 in the Gregorian system, as in the West. In 1912, Sun declared China would “use the lunar calendar for farming and use the Gregorian calendar for counting and classification.” This is reflected in the names China still uses for the lunar and Gregorian systems, nongli (农历 “agricultural calendar”) and gongli (公历, “public calendar”), today.

Just months into 1912, Sun stepped down and gave way to the military general Yuan Shikai (袁世凯), who became the first president of the new Chinese republic. Yuan retained Sun’s calendrical reform and ruled that on January 1, all shops and restaurants had to close and people had to return to their hometowns for New Year celebrations. Violators could even receive a fine. Government officials were asked to take the lead to celebrate the Gregorian New Year. With the lunar calendar considered a part of China’s best-forgotten imperial past, Yuan decreed that there would be no holiday during the Lunar New Year, with all citizens required to work as normal.

Unsurprisingly, the new rules triggered strong resistance nationwide. On the first day of the Lunar New Year in 1913, citizens across the country continued to celebrate as in previous years despite the official regulations. As a compromise, the Interior Minister Zhu Qiqian (朱启钤) suggested to Yuan that the traditional Lunar New Year, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, and Winter Solstice be reinstated in the public calendar under the names Spring Festival, Summer Festival, Autumn Festival, and Winter Festival, so as to respect folk customs and traditions while still promoting the Gregorian calendar.

Yuan partially agreed, and designated the Spring Festival a new holiday in the place of the Lunar New Year in 1914. It is because of Yuan and Zhu’s compromise that the term Spring Festival (春节) is still used for the Chinese Lunar New Year today. Yuan ruled that the Gregorian New Year on January 1 would still be the larger celebration, with a four-day public holiday, while the Spring Festival would only consist of a single day off (instead of seven days as it had typically been in the past). Government officials were forbidden from observing the Spring Festival altogether. On the Gregorian New Year, officials, military leaders, and even ”living Buddhas (revered figures in Tibetan Buddhism)” would send gifts and blessings to the president.

The revamped Lunar New Year coexisted with the Gregorian New Year until 1919 when the May Fourth Movement reignited the desire to do away with old customs and traditions in the hope of achieving modernity and development. Many students and reformers who took part in the May Fourth Movement saw the Gregorian calendar and New Year as a symbol of scientific progress while the traditional lunar calendar and Lunar New Year celebrations were considered superstitious, backward, and wasteful. Traditional offerings made to gods were widely criticized as unscientific, while the popular Shanghai newspaper Shen Bao criticized setting off firecrackers as a waste of money that generated pollution. The “lucky money” traditionally gifted to children was attacked for teaching the young to be greedy and selfish.

Criticism of traditional culture only grew in the 1920s. Shen Bao once compared the Lunar New Year to the feudal warlords who controlled parts of the country as their own fiefdoms, suggesting the abolition of Lunar New Year would be analogous to defeating the warlords. Influential literary magazine New Youth founded by Chen Duxiu (陈独秀), who later co-founded the Communist Party of China, concluded that persisting with old customs like the Lunar New Year would prevent the country from developing.

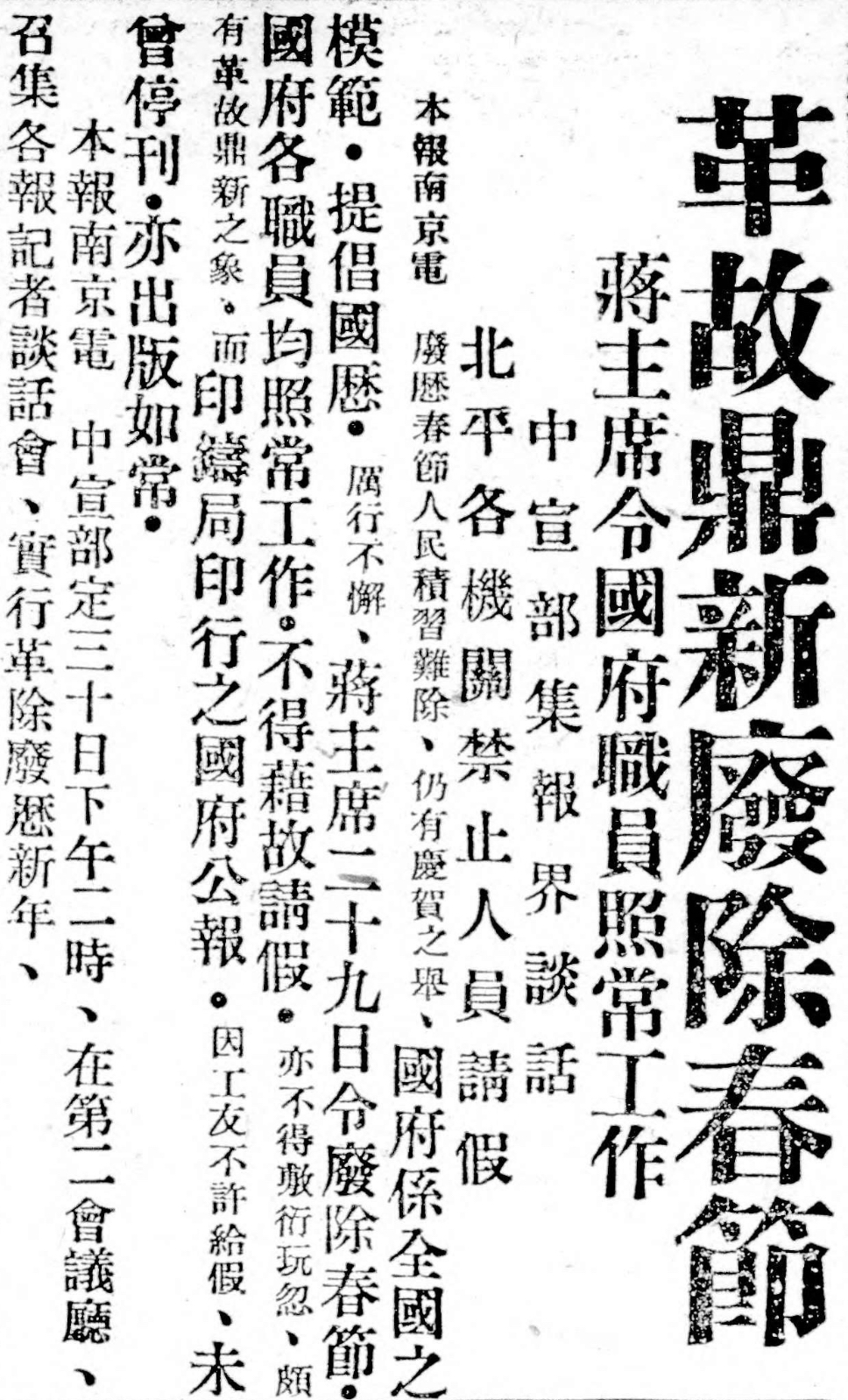

Efforts to remove the traditional calendar from public consciousness continued after Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石) united the country and established a new Nationalist government in Nanjing in 1928. To reinforce the Calendric Law first implemented by Sun Yat-sen, the Interior Ministry proposed eight regulations, including a ban on sales of lunar calendars and explicitly forbidding all government and public institutions across the country, including schools, from having holidays related to the lunar calendar. Chiang approved, and in December 1928 his government formally abolished the traditional lunar calendar along with Yuan’s Spring Festival.

***

***

Under the law, holidays, fireworks, Spring Festival couplets, and new year visits were all forbidden, and shops had to stay open during the Spring Festival. Violators would be punished with detention or fines; even calligraphers who made a living writing rhyming couplets used as decorations could face being detained by police. Civil servants also faced strict requirements. There were even rumors that one official of the Kuomintang (the ruling Nationalist Party) was made to stand for hours in front of a statue of Sun Yat-sen as punishment for saying “I wish you prosperity” to someone during the Lunar New Year.

But many people still celebrated covertly at home, and in rural areas, where law enforcement was lax, many celebrated with the normal family dinners and fireworks during the Lunar New Year of 1929.

Facing a Japanese invasion and a Communist guerrilla insurgency from 1931, the Nanjing government placed less priority on implementing enforcing calendar laws. In January 1934, Chiang finally repealed the ban, stating: “As to the lunar calendar (with the exception of government departments), there shouldn’t be too much intervention in folk customs.” Though there was no official holiday during the Spring Festival, the public could celebrate it openly again. Even the writer and satirist Lu Xun (鲁迅), once a staunch critic of Chinese tradition and old customs, changed his tune in his 1934 essay “Celebrating Spring Festival (过年)” stating, “Such celebrations cannot be so lightly discarded just by saying they are ‘feudal remnants.’”

When Chiang’s government collapsed and the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, the new government reverted to Yuan Shikai’s 1914 compromise of using the Gregorian calendar for Yuandan but still celebrating the Lunar New Year as the Spring Festival. For today’s workers, that means a short break around January 1, but not long to wait for a longer holiday at the beginning of the lunar calendar.

— Yang Tingting 楊婷婷, When China Banned the Spring Festival and Ended Up with Two New Years, The World of Chinese, 1 January 2023

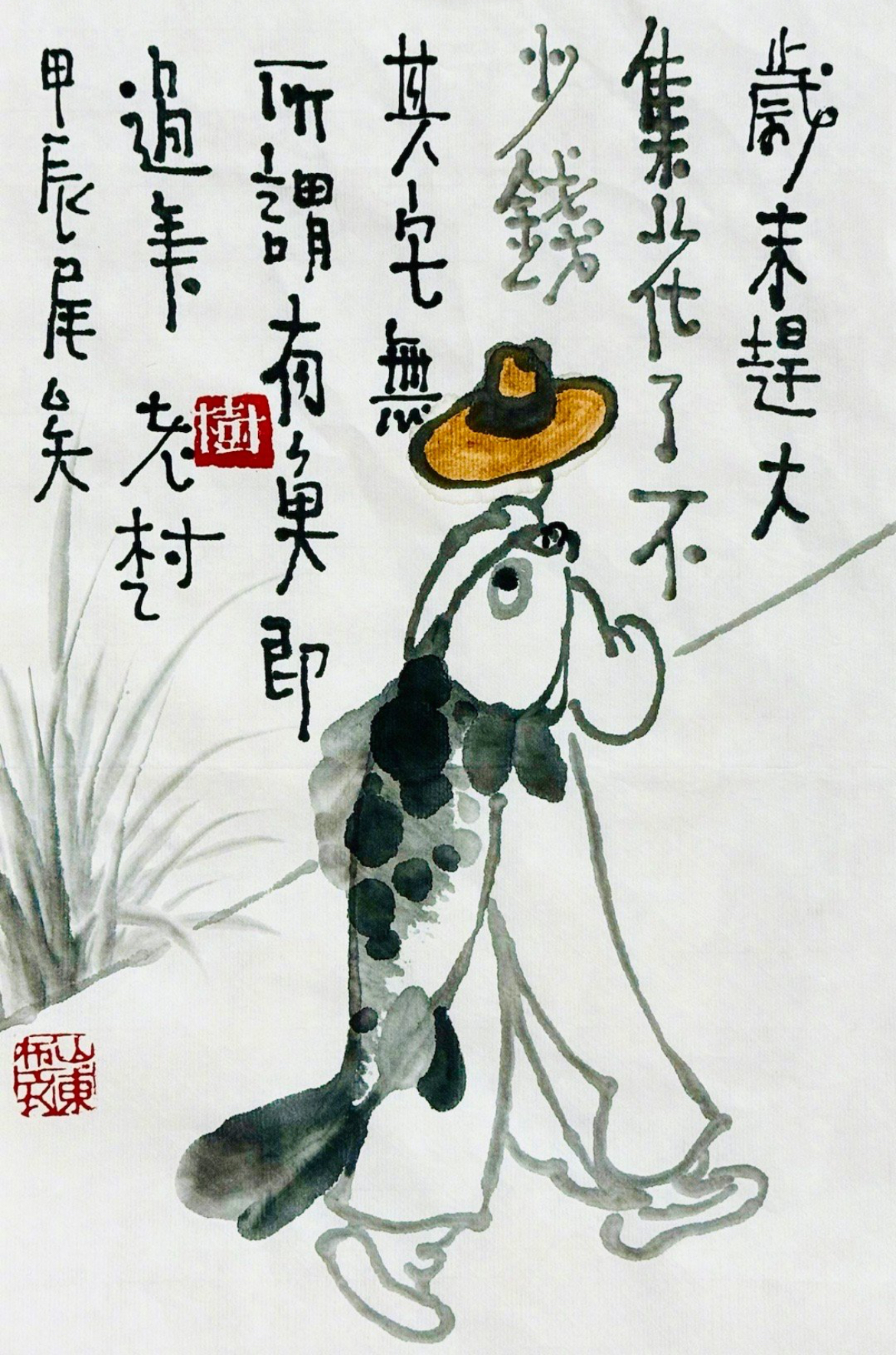

Made it to the end-of-year market,

where I really did let myself go.

None of that really mattered, though,

since I’d scored myself a New Year’s Fish.

— Lao Shu, at the tail-end of the Year of the Dragon.

Published on 27 January 2025

***

A Fish Every Year

年年有餘

The New Year’s Eve reunion dinner (tuan nian fan) is at the heart of Lunar New Year celebrations all over the world. Traditionally, family members return to their ancestral homes for a sumptuous banquet of home-cooked dishes, followed by a week or two of idling and visiting relatives and friends. In rural areas of China, home-reared pork is often served, along with chicken and a whole fish, the latter because the phrase “a fish every year” (nian nian you yu) sounds the same as “a surplus every year”. But as the Chinese world is on a scale to rival Christendom, local festive food customs vary as much as global Christmas dinners. In the wheat-eating north of China, people traditionally prepare jiaozi dumplings, while the Sichuanese steam fat slices of pork belly in clay bowls packed with salted vegetables. In many parts of the country, families gather around bubbling hotpots packed with meatballs, quail eggs, chunks of pork belly and other delicacies.

While the symbolic whole fish is almost ubiquitous on the Chinese festive table, the Cantonese are particularly playful with the auspicious meanings of their New Year dishes (the Chinese language is replete with homonyms and therefore ripe for punning). Slabs of New Year Cake, a sweet pudding made from glutinous rice, are eaten over the holidays because their name, nian gao, plays on another word with the same sound (gao): “higher” — in wealth, school grades, status or stature. In advance of the festivities, people gift each other coupons that can be redeemed at specific restaurants or shops for this and other seasonal cakes, also known as gao, made from radish and taro (“radish cake futures,” my Cantonese friend Roberta quips). Kumquats and mandarins are served because their golden colour invites prosperity, along with ruddy deep-fried chickens — red being the traditional colour of Chinese celebrations.

In Hong Kong and other centres of Cantonese society, restaurants create menus of lucky-number eight dishes, each one with a name that signifies luck, wealth or one of the other bonuses of life. …

Cantonese food customs have spilled over into diaspora communities. Chinese restaurants all over the world offer New Year cakes and symbolic menus. In recent years, an auspicious Singaporean dish has become wildly popular in Chinese circles all over the world: yu sheng [魚生], or “prosperity toss”. A colourful assembly of shredded ingredients, including raw fish, are bathed in a sweet dressing, then everyone around the table tosses the food together with their chopsticks while voicing good wishes for the year ahead — and the higher the ingredients fly above the table, the “higher” the luck. This year, far from China … I’ll be celebrating over a home-cooked Shanghainese feast in London — and I’m looking forward to tossing the prosperity salad while welcoming the Year of the Snake.

— Fuchsia Dunlop’s culinary guide to Lunar New Year, 25 January 2025

***

Vipers and Beasts in the Year of the Little Dragon

In the early 1960s, the artist Huang Yongyu 黄永玉 produced his own ‘devil’s dictionary’ (The Devil’s Dictionary is the title of Ambrose Bierce’s famous 1906 collection of satirical, and cynical, re-definitions of commonplace terms). Huang compiled his pithy sayings and made pictures to accompany them. Most took their inspiration from animals and insects. Below we reprint the snake from Huang’s bestiary which is known in English both as A Can of Worms and Animal Crackers.

***

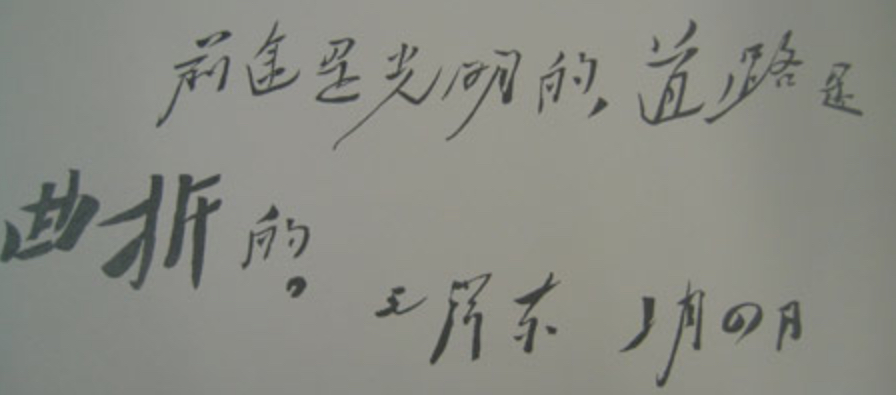

(They say the path forward is tortuous; that’s why I have such a supple body.)

***

In the People’s Republic of the 1960s, anyone who saw (or heard about) Huang’s snake and the accompanying epithet would have appreciated the pointed reference to Chairman Mao and his famous statement about the troubled path of the Chinese revolution:

The future is bright, but the path forward is tortuous

前途是光明的,道路是曲折的。

***

***

Mao is said to have made this remark during his September 1945 visit to the wartime capital of China, Chongqing, where, following the end of the war with Japan, the Communists and Nationalists attempted to negotiate another truce in their decades-long hostilities. While there Mao met with the noted left-wing writer and Communist agent of influence Guo Moruo 郭沫若. Guo presented the Chairman with an Omega watch that he used for the rest of his life; for his part Mao uttered his lapidary words about the winding road to victory. Mao included the line ‘The future is bright, but the path forward is tortuous’ in the conclusion to his ‘On the Chongqing Negotiations’ 關於重慶談判, his report on the talks offered to Party cadres back in the Communist base of Yan’an on 17 October 1945.

Huang Yongyu started making his ‘animal crackers’ at the end of a lapse in the rising tide of Maoist extremism. As the artist recalls:

I started creating these ‘animal tidbits’ during moments of boredom and frustration while in in Xingtai in 1964. It was just before the earthquake and I’d been sent to a commune production brigade there as part of the ‘Four Cleans’ Campaign. Eventually, I found I had a collection of over eighty of them. Some comrades who saw them thought they were great fun, laughing so hard they couldn’t stand up straight. I too was pleased with the result and thought I’d try and publish a small volume of them, with illustrations, when I got back to Beijing.

The Four Cleans 四清運動 was the rural prelude to the Cultural Revolution, but many writers and artists had thought that following the depredations of the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s and early 1960s more moderate policies, and economic growth, would continue. Among the most famous writers to take advantage of the relatively relaxed post-Leap policies was Deng Tuo 鄧拓, a Party loyalist and noted essayist. His Evening Chats at Yan Mountain 燕山夜話 remain a delight; another is Huang Yongyu and his far less-well-known ‘animal crackers’. While Deng’s musings appeared in the Beijing Evening News, Huang’s ‘tidbits’ circulated only among his intimates, a group that included members of The Layabouts Lodge 二流堂, one of the only pre-1949 literary salons that survived into the People’s Republic. However, as is so often the case with pithy humour and private social commentary, ‘animal crackers’ soon found a wider audience.

During his ‘re-education’ in the following years, the artist was repeatedly interrogated about the comic lines and their heinous politics. The originals were lost in the maelstrom of the Cultural Revolution, and the image above is part of a set of images that Huang published under the title Jottings from the Bottle Studio 罐齋雜記 in 1983, just as the Party’s Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign was taking shape.

— adapted from Geremie R. Barmé, Vipers and Beasts in the Year of the Little Dragon, The China Story Journal, 8 February 2013

[Note: For the full set of animal crackers, images and text in English and Chinese, see Huang Yongyu: A Can of Worms in the multimedia section of the Morning Sun archival website.]