The Other China

天下本來無事,糾結只在人心。

以為有分有別,其實無古無今。

The world itself is without strife, it’s just people’s hearts that make it so. As for all of those differences and distinctions, in reality there is neither the past nor the present.

— Lao Shu

A Record of Journeys to the West 西行記 is the title of an exhibition of fifty-four paintings, six painted porcelain objects and a hand scroll by the Beijing artist Lao Shu held at the Gansu Bamboo Slips Museum in Lanzhou. The work was created during numerous trips to and travels around China’s Hexi Western Corridor over a decade.

In a speech delivered at the opening of the show on 28 September 2024 titled ‘Neither Past Nor Present — another way of seeing’ 無古無今——視覺表達的一種可能性, Lao Shu spoke about his long-term endeavour to travel unimpeded through Chinese space-time as an artist. It is a topic that we previously featured in The Other China. See, for example:

- Lao Shu — roaming through Tang-Song landscapes with my Wei-Jin brothers, 13 July 2024;

- On a bed of blossoms, dreams take me to the Tang, 26 August 2024; and,

- An Express Delivery from the Tang Dynasty, 18 September 2024.

As Lao Shu said of the exhibition:

In the summer of 2015, I travelled the Hexi Corridor, from east to west. It was a moving journey of discovery: wall paintings in the Mogao Caves, the Buddhist sculptures, the painted bricks from Wei-Jin-era tombs, painted potters, the bamboo slips, as well as the crops growing in the fields, the wild blossoms at the roadside, the people in the towns and the variegated scenery … It’s what led me to think about painting what I had seen, felt and thought during my travels in the west.

What I mean by ‘there is neither past nor present’ is that I believe that painting opens a passageway into the past. For example, I can invite people from the Wei-Jin era, over a millennium in the past, to travel with me into the Tang dynasty.

2015年夏天,從東到西在河西走廊跑了一趟。洞窟壁畫、佛造像、魏晉墓葬畫像磚、彩陶、簡牘,地裡長的莊稼,路邊開的野花,城區人事,風物山水……一路看過去,大受震撼。於是,起意要來畫一畫這趟西行的所見所感所思。

無古無今,實際上是指通過繪畫的方式打通古今,比如邀請1000年前魏晉時期的人,和我一起到唐朝去旅遊。

— “老樹”西行記:畫里甘肅“無古無今”,鳳凰網,2024年9月28日

***

***

與魏晉兄弟

游唐宋河山

Travelling through Tang-Song landscapes

in the company of my Wei-Jin brothers

My eyes feast on boundless green delights

moving amidst the vicissitudes of the ages

— Lao Shu, inscribed on a four-sided porcelain

vase in heavy rain, mid-summer, in the

Jiachen Year of the Dragon (2024)

Lao Shu 老樹 is the nom de plume of Liu Shuyong (劉樹勇, 1962-), a Beijing-based artist, writer, critic and professor in communications. His artistic voice is unique and personal, its tenor, whimsy and profundity evoke what for decades we have called The Other China — a cultural noosphere that is as undeniably local as it is universal.

As Lao Shu notes in a few sparse lines inscribed on a porcelain vase on a rain-drenched summer’s day in the 2024 Year of the Dragon, his art evokes a world that draws inspiration from his mind-travels in the landscapes of the Tang and Song eras (early seventh to the early twelfth centuries CE). During his ventures he enjoys a fellowship with the eccentrics and prickly individuals of the Wei-Jin period (third century to the mid sixth century CE), one known for moments of splendour amidst waves of murderous political disorder. …

For details of the Wei-Jin era in the series The Tower of Reading, see the chapters from New Tales of the World 世說新語:

As well as the work of Tao Yuanming (陶淵明, 365-427 CE), the famed recluse-poet who rejected service to the state to pursue a life of leisure, writing, drinking, and occasional agricultural pursuits. As we noted in Substance, Shadow, Spirit 形影神, Tao’s quest for quietude, one tinged with worldly concerns, indulgences and fears, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists and writers alike.

Lao Shu’s work continues in that ancient lineage and it offers what Feng Zikai 豐子愷 called ‘a temporary escape from the dusty world’ 暫時脫離塵世.

— from Lao Shu — roaming through Tang-Song landscapes with my Wei-Jin brothers

***

A Record of Journeys to the West is part of Lao Shu’s deft cultural exploration, one that in certain respects resonates with what the historian Leo Ou-fan Lee called ‘the romantic generation’ of the May Fourth era. Then, and again in the 1980s — when Lao Shu came to his maturity — there was ‘a new emphasis on sincerity, spontaneity, passion, imagination—in short, the primacy of subjective human sentiment.’ (Lee, ‘The Romantic Temper of May Fourth Writers’ (1973).) Generation after generation of ‘China’s romantics’ has either been subsumed by politics or silenced by the clamour of the collective, until recent times, that is. One of the many ironies of the Xi Jinping New Era is that the promotion of ‘cultural confidence’ has given license to a range of romantic aspirations that are beyond the ken, and often beneath the interest, of the bureaucratic state.

Lao Shu enjoys a utopian commerce with the past, one that also happens both to be commercially successful and happily in sync with the cultural archaeology of the day. The artist says that he invites the past into present in a process that discombobulates space and time. This intermingling of Yin and Yang 陰差陽錯, the reverse engineering of Qian/ Heaven and Kun/ Earth 乾坤倒轉 is the kind of trans-temporal artifice — variously called 時空旅行、時光旅行 and 穿越時空 in Chinese — that is generally forbidden in audio-visual culture for the threat it poses to the stodgy order and historical determinism of the party-state.

Our artist’s romantic self-obsession takes concrete form in his narrative work. Lao Shu’s alter ego is a man of a certain age dressed in a white scholar’s gown wearing traditional black-cloth shoes and with a fedora on his head. His face is featureless although hardly blank, since the artist is omnipresent in both image and word.

Lao Shu issues a modest invitation to the viewer; it is a comforting welcome that takes sly advantage of the modish cultural assertiveness of the era. His timescapes are free of the agita that is all too common in a cultural industry propped up by vainglorious and evanescent whims, be they political, commercial or digital. The artist’s two-way trade with the past extends his quest to share an individual vision and sensibility while gently nudging others to pursue their own search for self.

The temper of Lao Shu’s work is light-hearted, quizzical and irreverent. It confronts without challenging, questions without declaiming. Rarely in today’s China have the weighty themes of time-space and cultural dissonance been juggled by such an assured hand.

***

The paintings on fan faces featured below include texts and colophons in black ink style with red artist seals. The framed paintings, many of which take motifs from the votary Buddhist grottoes of the Mogao Caves 莫高窟 near Dunhuang, Gansu province, include two or three kinds of text box, differentiated by the colour of the background, although the only rhyme or reason behind this is visual. The artist’s poetic observations are usually in turquoise; explanations of the inspiration for a particular work and reference to the origin of a particular motif in colophons are frequently in brown; and, signature panels which include a date and sometimes even a note on the weather conditions at the time the work was made tend to be in orange or yellow. All of the works in this selection can be found in Lao Shu’s Weibo account: 老樹畫畫.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

16 October 2024

The 50th anniversary of arriving in

Beijing to study in October 1974

***

The photographer Lois Conner, a long-term collaborator with China Heritage, arrived in China in October 1984 with a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue her interest in the visual culture of that country and to explore through her own lens Chinese ways of seeing and ways of seeing China. She studied for a time at Peking University, where she acquired the rudiments of the spoken language, before going to spend months at Dunhuang recording the Mogao grotto caves for a major international project.

This essay in The Other China is also a celebration of the four decades during which Lois has pursued her artistic vision in China.

— GRB

Only ever one step away

Lao Shu’s Hexi Paintings

selected, translated and annotated by

Geremie R. Barmé

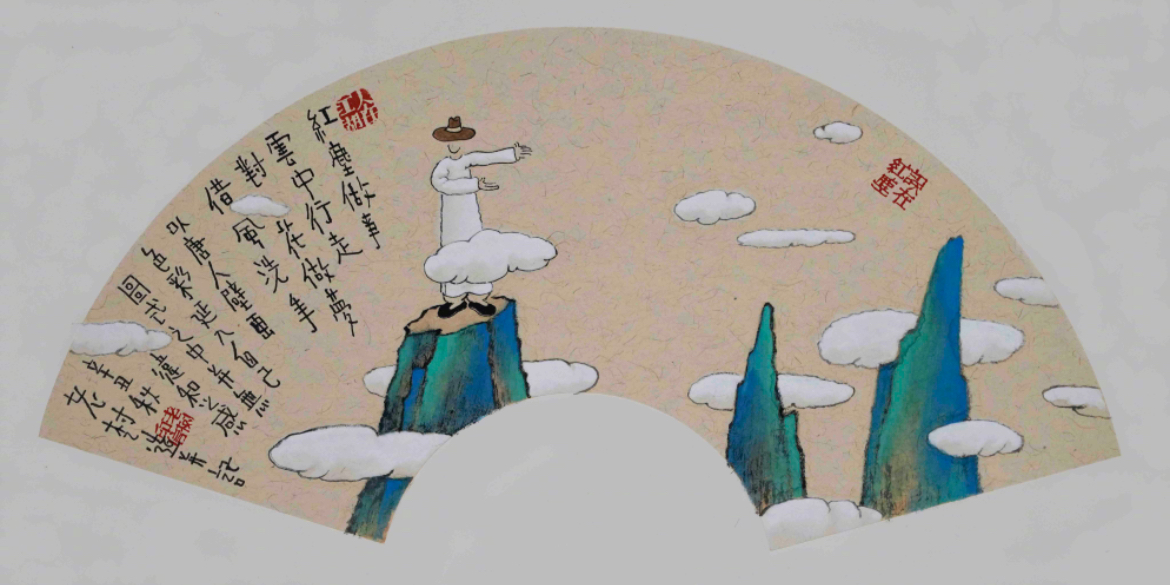

Work may be in the Dusty World,

Travel though is through the clouds.

Dreaming I do with the flowers,

Just as the winds cleanse my hands.

I don’t think that it is all that inappropriate to introduce some of the brilliant hues found in Tang-dynasty wall painting.*

— painting and commentary by Lao Shu, autumn, Xinyou Year of the Ox

* The blue-green landscape style 青綠山水 of the Tang and Song eras features prominently in Lao Shu’s Western Corridor series.

***

I was chatting with a friend from the Jin dynasty,*

telling him about everything that’s been going on:

There’s news about the Russo-Ukraine War

and developments in the Hamas-Israel conflict.

Add to that the U.S. presidential election,

not to mention China — which I didn’t mention.

After hearing me recount all of these goings on,

he said he felt as though his head would explode.

‘Let’s stick to drinking; see how brilliant the fire.’

— painted by Lao Shu in the Jiachen Year [2024]

* The Jin dynasty was part of the Age of Disunity, one of the most tumultuous periods in Chinese history. It was also an age of exuberance.

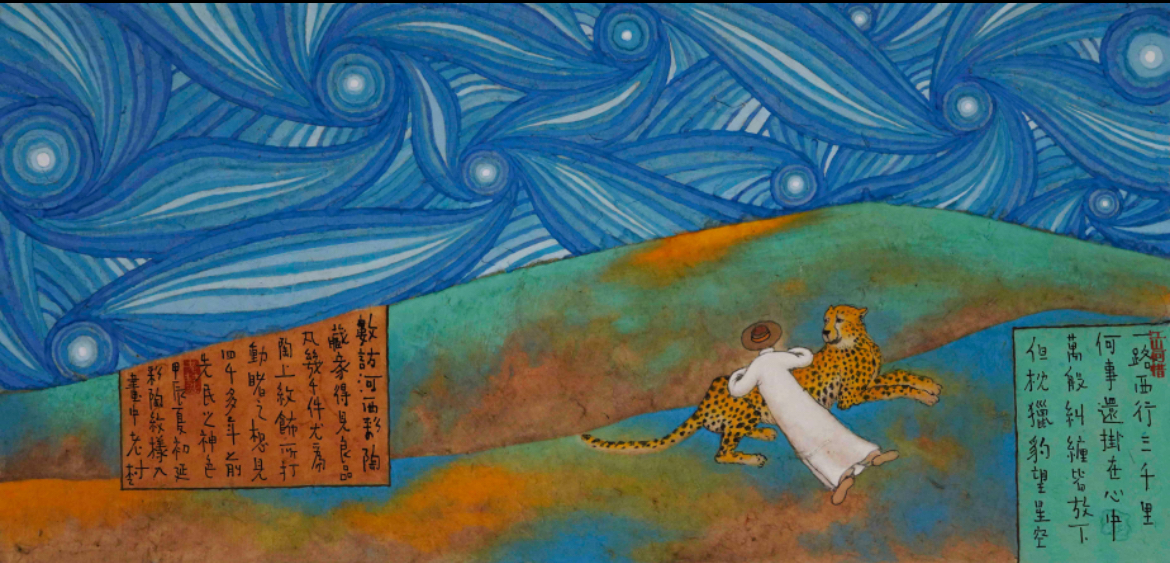

Having travelled three thousand li to the Far West,

what things could possibly still weigh me down?

All of those concerns have long been put aside as

I snuggle on a leopard and gaze heavenward to the stars.

Colophon: I’ve been to Hexi [in Gansu province] a number of times and met a collector of ancient painted pottery. The patterns on pottery created by people over four thousand years ago communicates something of their unique spirit and I’ve added some of those old designs to my own work.

— Lao Shu, early summer, Jiachen Year of the Dragon

***

I came across a traveller in the mountains

who claimed they were from the Jin dynasty.

They inquired about the way

that would take them to the Tang.

I replied that it is a distant landscape

obscured by white clouds along the way.

It’s sure to take you a few centuries;

hope we’ll be able to stay in touch.

Colophon: Inspired by the wall paintings at Mogao Cave 196 [the rest of the inscription is unclear].

— Lao Shu, Jiachen Year of the Dragon

***

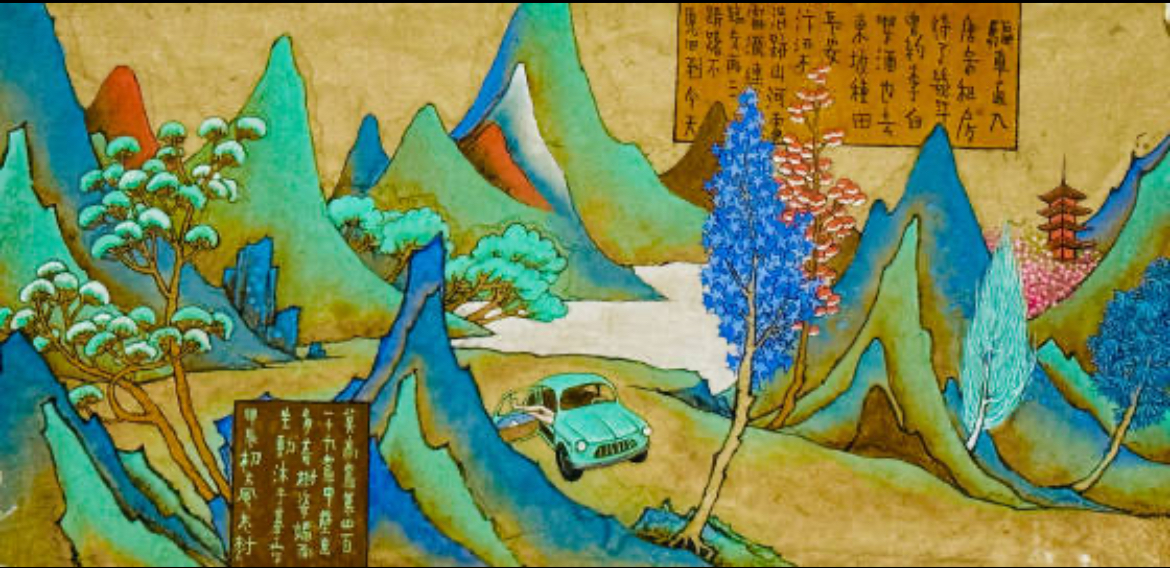

I headed straight into Tang-Song times by car,

rented a place and hung around there for a while.

I once invited Li Bo to get drunk with me

and hung out planting fields with Su Dongpo.

I wandered all over Chang’an and Bianliang,

and lingered enjoying the landscape.

I hesitated for ages before taking my leave,

reluctant to come back to the here and now.

Colophon: Many of the bizarre trees depicted in the wall paintings at Mogao Cave 419 appealed to me and I’ve tried to incorporate a sense of them in my work.

— Lao Shu, early in the Jiachen Year of the Dragon during a windstorm

***

I invited a friend from the Eastern Jin

to join me on a trip to the Tang dynasty.

It’d been a millennium since we’d caught up

so we fell into deep conversation, he and I.

Both landscape and misty wonders were unsullied,

petals falling from the trees in the small garden.

The passage of months and years is no real barrier,

for those who are of a mind are only ever one step away.

Colophon: I see no reason why someone from the Jin dynasty could not encounter an auspicious creature from Tang times, nor indeed what is incongruous about taking a drink from a David Hockney swimming pool.*

— a painting inspired by reflections on what I saw during my travels along the Hexi Corridor at the height of summer, Jiachen Year of the Dragon. Lao Shu

* In the 1960s and 1970s, the artist David Hockney used Los Angeles swimming pools as the setting for many of his works.

***

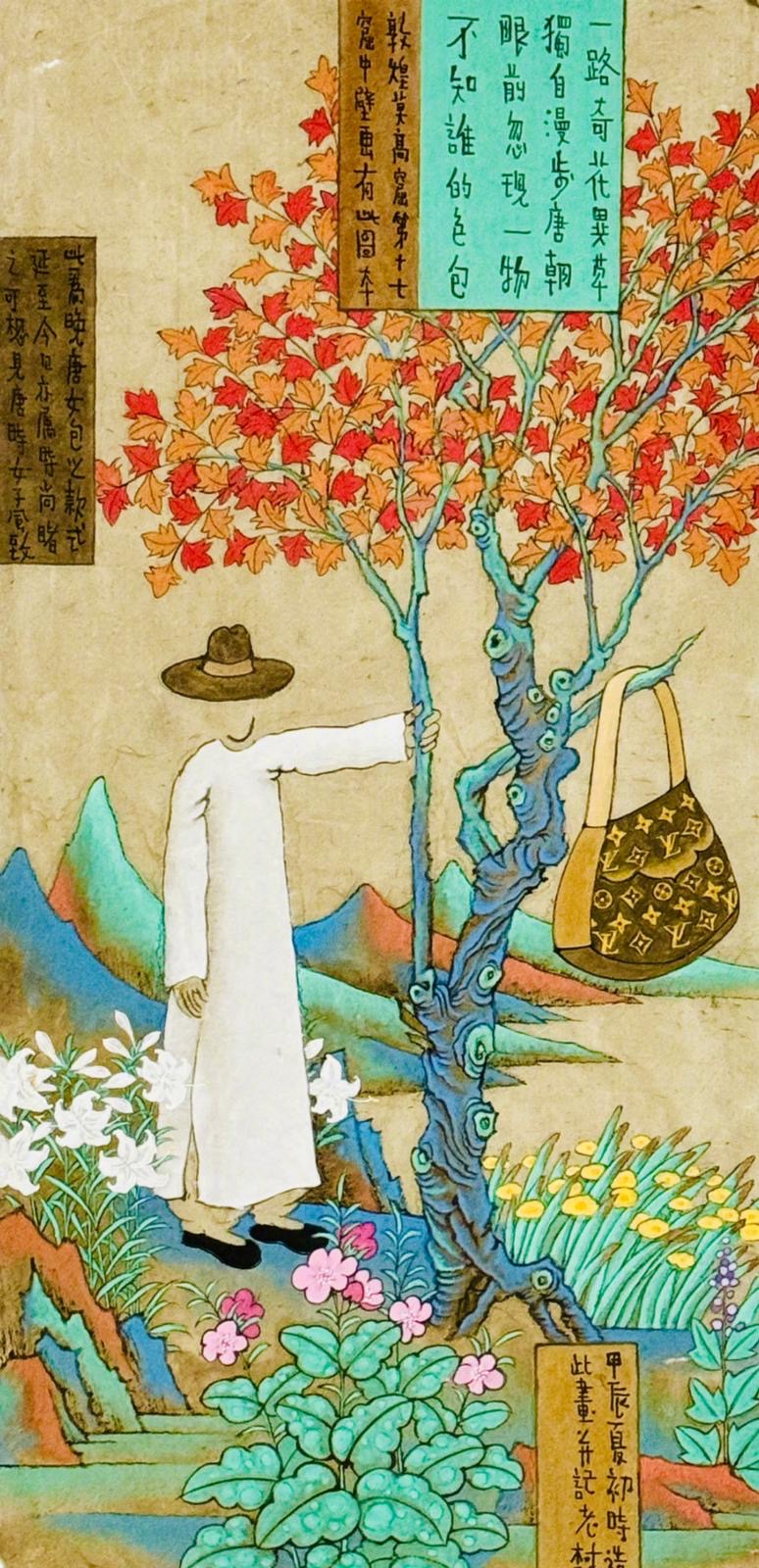

Phantasmagorical vegetation grows along the path,

as I wend a solitary way into the Tang era.

But, what is that sudden apparition:

No idea who’s left their shoulder bag here.

Colophon One: You see this kind of flora depicted in the wall paintings of Mogao Cave 17.

Colophon Two: The handbag was fashionable in the Tang though, if you see it in terms of the present day, they’re really just like a [Louis Vuitton] designer bag.

— I made this painting and recorded these words in the early summer of the Jiachen Year of the Dragon. Lao Shu

***

In the company of an old friend from Hexi

and a young buddy from Guoyuan-Xincheng

hanging out beyond Jiayuguan at dusk

was a rare moment for us all.

Though each was weighed down with concerns,

we enjoyed braised lamb and drank mightily

parting only in the deep of night when

Heavenward the sky was full of stars.

Colophon: An evening excursion beyond the Pass. The crenellated walls of the Jiayuguan fortress stood stern and solemn.

— Lao Shu, Jiachen Year of the Dragon

* Guoyuan-Xincheng [tombs] 果園—新城[墓群] is an archaeological site between the towns of Guoyuan and Xincheng, near Jiayuguan in western Gansu province. There are over 1400 ancient tombs in an area of approximately sixty square kilometres that date from the third to tenth centuries. The area was declared a culturally significant zone in 2001.

***