Ruling The Rivers & Mountains

穩坐江山

This Lesson in New Sinology is published on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the opening ceremony of the XXIXth Olympiad in Beijing (for an analysis of that event, see China’s Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008). Official China acknowledged the three decades dated from late 1978 since Communist Party policies had actually helped the country achieve the kinds of prosperity promised thirty years earlier (from 1949), hopes long betrayed by Party infighting and misdirection, with disastrous consequences. Freed of Party dogma, by 2008 China had been economically remade; with the diminution of policies to protect the socialist ideals, and egalitarianism in areas such as education, health and employment, of the Party’s original mission, however, the country had also become a haven for egregious behaviour and state-sanctioned capitalism.

For Non-Official China, 2008 was a very different place. In preparation for what the international media blithely celebrated as ‘China’s Coming Out Party’, the party-state had invested massively in new technologies and training related to the dark arts of social control. The repression of dissent, the bloody crushing of protests in Tibetan China, increased policing of the media and the expansion of social surveillance were all much in evidence.

The 2008 Olympics were, however, also an occasion when Chinese people more generally could rightly celebrate hard-won achievements and global recognition. Finally, after nearly sixty years, New China seemed more ready than ever before to embrace a broader humanity. The hope was summed up in the theme of the Beijing Olympics: ‘One World, One Dream’ 同一世界 同一夢想. This appeared to be an undertaking that would vouchsafe harmony, peace and prosperity for all; its reality actually reflected the party-state’s demands for compliance, which even then was being called The China Story 中國的故事. In fact, the darkness of Xi Jinping’s New Epoch (2012-) was in many respects adumbrated in 2008.

***

We start this five-part Lesson in New Sinology by considering an indoctrination campaign launched by the Communist Party on the eve of the tenth anniversary of the Beijing Olympics. The ‘Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise in the New Epoch [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動 was fortuitously announced on 29 July 2018, only days after Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing, had published Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待 (trans. with notes, China Heritage, 1 August 2018), although that is not to suggest that the two were connected.

In his powerful petition Xu had warned against the dangers of, and the potential disruption caused by, new political campaigns. He expressed concern about a party, insecure in its rule, targeting the country’s disgruntled intellectuals, in particular academics who had studied overseas, and treating them as scapegoats for its own political deficiencies. The announcement outlining the aims of the new patriotic offensive was couched in the vague, obfuscating language generally favoured by today’s Party ideologues in public. In private most knew that, in essence, this latest ‘cultural pogrom’ was really about Thought Reform 思想改造 and Political Thought Work 思想政治工作, that is quashing dissent and re-moulding the ideas, attitudes and speech of individuals so that they would accord with the prioritities and needs of Party policy.

From the late 1930s, ‘Thought Work’ had played a crucial role in regimenting and unifying the thinking of the Communist Party men and women from disparate regions and backgrounds who found their way to the wartime revolutionary guerrilla base at Yan’an in Shaanxi province 陕西延安. Military might would bring the Communists to power in 1949, but it was ideology, long-term and focussed political study, as well as the body of ideas known as Mao Zedong Thought that laid the basis for what the Communists, using an ancient expression, would call ‘Conquering All Under Heaven and Claiming Rule over The Rivers and Mountains [of China]’ 打天下,坐江山.

In ‘The Rivers & Mountains 穩坐江山’ (an expression that means ‘confidently ruling China’), the first of a five-part series, we offer an account of some aspects of Thought Work in the People’s Republic, as well as accounting for its pre-1949 practice in Yan’an. In the process, we also tell the story of one of the Communist Party’s most important thought-policemen, Hu Qiaomu (胡喬木, 1912-1992). Through introductory essays, translations, works of fiction, media reports and art work, this Lesson in New Sinology aims to help familiarise readers with a range of Party practices, and resistance to those practices, relevant to appreciating Xi Jinping’s New Epoch.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

8 August 2018

Preface: Mind Melding in Times of Conflict

The People’s Republic of China was founded in conflict, primarily because it was the result of the victory in a civil war with the Nationalist-led government of the Republic of China. But with that triumph the Communists were also victorious over the United States, a country they regarded as being the supporter not only of the Nationalists, but more generally of imperialist designs on and the exploitation of China itself.

In White Paper, Red Menace — Watching China Watching (VII) (China Heritage, 17 January 2018), we discussed the impact of the American government’s ‘China White Paper’ (the full title of which was United States Relations With China, With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949), released on 5 August 1949. The White Paper’s avowed support for a democratic China against a communist-dominated government beholden to the Soviet Union would bolster the anti-American arguments that Mao Zedong, the leader of the Communists, had been making for many years. In a series of Five Critiques of the White Paper (excerpted in White Paper, Red Menace), which he wrote with the help of his secretary Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, Mao laid out what essentially remains the ideological basis for China’s opposition to the US, in particular during periods of conflict, today.

The Korean War (25 June 1950-27 July 1953) — known in official Chinese as 抗美援朝 (the War to Resist American Aggression and Aid Korea) — locked the two powers in direct conflict. While that conflict ravaged the Korean Peninsula, another battlefront was claiming its own victims in Beijing. Mao and his colleagues knew that their control over China’s intelligentsia was based both on the latter’s patriotic yearnings, as well as the Party’s promises made over the years since the end of the Sino-Japanese conflict in 1945. The Communists had made extravagant undertakings in relation to their support for human rights, democracy and intellectual freedom, all of which most members of the intelligentsia felt had been denied to them by the Nationalist government during the Civil War. But, from late 1949, now that they were in power — having ‘Conquered All Under Heaven and Claiming Rule over The Rivers and Mountains [of China]’ 打天下,坐江山 — the Party quickly unveiled their real agenda, and they needed the continued support, and compliance, of the intelligentsia to achieve it. To that end, Party organisations at the key centres of higher education, Peking and Tsinghua universities in Beijing, set about creating a model to be followed nationwide to achieve the mental transformation of university teachers, scientists, researchers, publishers, and the cultural world more generally. This ‘intellectual rectification’ would be called the Movement to Remould Thinking 思想改造運動.

As we noted in Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily (China Heritage, 10 July 2018), the Communists had carried out a lengthy, and at times violent, Rectification Movement 整風運動 in Yan’an in 1942-1943. From late 1949 up to the autumn of 1952, they would apply the lessons of Yan’an to the universities and publishing houses of the whole country. Although the Thought Reform that was launched at Peking and Tsinghua universities was informally known as a movement to ‘Drop Your Pants, Cut Off Your Tail, Get in Line to Wash in Public’ 脫褲子,割尾巴, 排隊洗澡, out of a reluctant consideration for the sensitivities of the intelligentsia, and women in particular, it was simply called ‘Washing in Public’ 洗澡.

The process of ‘cleaning up’ the intelligentsia was, nonetheless, rigorous, tireless and in some cases merciless. Just as in Yan’an, there were casualties and deaths. China has never entirely recovered from that transformation. Observers, and even many people in the People’s Republic of China, may think that since the Communist Party negated the ‘leftist’ extremism of the Cultural Revolution in a formal Party Resolution in 1981 — one that also criticised the supposed origins of Mao’s wilful authoritarianism from the late 1950s — the policies of violent class struggle, the physical elimination of class enemies and brutal political campaigns that proceeded it would be of little relevance to understanding China in the twenty-first century. In fact, the purges, murders and liquidations of the early to mid 1950s have never been repudiated. They are regarded by the authorities as foundational to the history of the People’s Republic and the creation of a strong, industrialising and cohesive nation that, since the launch of economic reforms in 1978, has achieved greatness.

***

In 2018, as the United States and the People’s Republic became embroiled in a Trade War, the long-forgotten history of ‘Washing in Public’ from 1949 to 1952 comes to mind. When, on 31 July 2018, a joint news release by the Communist Party’s Organisation and Propaganda (Publicity) departments announced a new patriotic education campaign — ‘An Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise in the New Epoch [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動 — it was doing so at a time when international concern about Chinese scientific and industrial espionage as well IP theft by agents or those sympathetic to the People’s Republic was at a new height, in particular in relation to the Made in China 2025 中国制造2025 strategy which was aimed at the country achieving major industrial and scientific advances. The 2025 plan was, like previous Party programs, a mixture of the technical and strategic, the overt and the covert. As the Sino-US trade clash continued the new patriotic campaign was launched in atmosphere of mounting paranoia and urgency. Regardless of its avowed aims, the campaign would focus in particular on the loyalty of returnee intellectuals, teachers, scientists and technicians educated overseas, in particular in the United States.

In the new millennium, as the Chinese economy boomed and society seem to be undergoing major transformations, many graduates had sought opportunities in the familiarity of ‘the old country’. It was reported that many hoped to benefit from the country’s ongoing economic rise, as well as being able to contribute their talents to the place of their birth. Behind the anodyne official talk of encouraging greater participation of talented individuals in achieving national goals, the 31 July announcement hinted that men and women who had returned from overseas were potentially tainted; perhaps the old Mao-era slurs about ‘dubious foreign liaisons’ 裏通外國, or ‘collaborating with the outside’ 裡應外合, and even ‘selling out the country for personal glory’ 賣國求榮 would come back into vogue? During the first term of Xi Jinping’s rule (2012-2017), Thought Moulding had already become a significant feature of religious and ethnic policy. With his reassertion of 360-degree-control by the Party, his administration pursued policies first introduced in the early 1950s, among them was an organised effort to eliminate independent religious practices and create pliant, pro-Party ‘patriotic’ faith communities. Following a lengthy analysis of the causes and consequences of the 2008 rebellion in Tibetan China, the authorities had concluded that the religious spirit of the region was a long-term threat to the Party. By effectively turning monasteries into study prisons and via sequestration, constant surveillance, the mandated collective study of political tracts, the use of individual confessions, intimidation of family members, and so on, patriotic thought re-moulding had been underway for years. Problematic individuals and groups were not so easily isolated in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, so over time Lager (concentration camps) were constructed for mass re-education. In 2018, the sheer scale of the plight of Uyghurs in Xinjiang seemed finally to alert the international community, and even many slow-witted China Experts, to what, in fact, were the range of repressive policies and coercive techniques that had long lurked at the core of the China Dream.

Proving loyalty to New China during the blood-washed conflict between the People’s Republic and the United States in Korea took many forms. Keeping a passport might be regarded as a sign of potential betrayal, or mistrust in the new government; foreign contacts would have to be monitored or severed; relatives or loved ones overseas could be a cause for suspicions, and so on. The individual’s guilt was also judged by just how much in thrall they were to the US, and a specific mini-campaign was even launched to ascertain people’s sentiments. It was aimed at assessing if the individual was pro-, worshipful or fearful of America 親美、崇美、恐美? From mid 1950, as the Korean conflict escalated, university-based intellectuals, along with their fellow citizens were also subjected to what was called a ‘Three Perspectives Education Campaign’ 三視教育運動. Through mass propaganda activities, films, art exhibitions, books, pamphlets and constant media reports, as well as collective study sessions that focused on reading, discussing and memorising key political texts, everyone would come to understand the true nature of the Paper Tiger 紙老虎 of Reactionary Imperialism; as a result they would finally be able to ‘Hate 仇視, Despise 鄙視 and Belittle 蔑視’ the United States. Because of the deep, long-term connections between many of China’s four million Christians and churches in the United States, believers were also a major target during the campaign.

Patriotising people in China in 2018 would take a myriad of forms: rote study sessions during which the deathless words and ideas of Xi Jinping would be read, mulled over and internalised, focus groups that concentrated on particular issues, individual guidance and ‘ideological wellness’ sessions were paired with the usual full range of inducements and punishments available to the Party apparat. The Chinese intelligentsia were living in the twenty-first century, but the jagged mechanisms of oversight and control exercised by the Communist Party had been at work for nearly eighty years. Intellectuals in Xi Jinping’s New Epoch who had already learned to self-censor and be vigilant about what they said in class, or in public, were gradually being re-educated, they were learning some of the same painful lessons as their predecessors.

For patriot-intellectuals seen as models of a loyalty that was married to professional acumen, there was the promise of reward. On 8 August 2018, for example, New China News Agency reported that sixty-two ‘representative’ outstanding scientists and experts were vacationing at the Party’s luxury seaside resort at Beidaihe 北戴河, Hebei province. They were guests of the State Council and Party Central. (See 林暉, 愛國奮鬥譜華章 建功立業新時代——黨中央、國務院邀請優秀專家人才代表北戴河休假側記, Xinhua, 8 August 2018).

Lessons in New Sinology

We launched China Heritage on 1 January 2017 with the publication of a mediation on Sino-US relations that focussed on the newly elected president Donald Trump and the China question (see A Monkey King’s Journey to the East). At that time, we also offered the Rationale behind our work in the form of an essay titled On Heritage 遺. That declaration of intent was prefaced by a quotation from China’s most famous, and ancient, oracular text I Ching 易經, or the Book of Changes:

For every plain there is a slope, 無平不陂,

For every going there is a return. 無往不復。

— Hexagram XI, I Ching 周易 泰掛繫辭

The main focus of China Heritage is the ways in which the past works in the present, in particular how aspects of China’s intersecting traditions of literature, art, thought and history commingle, emerge and reemerge in ways that celebrate both continuity and renewal, a phenomenon that was long ago framed by the word tōngbiàn 通變, invention within tradition. Tōngbiàn is made up of two elements: tōng 通, meaning a thoroughgoing familiarity with past practice, and biàn 變, the creative transformation of convention. Since much of the past pulsates with life in the present, we feel it is also relevant to introduce, or re-introduce readers, to historical moments, concepts and even words from China’s past. Apart from the excited neo-philia of much writing about, reporting on and research into contemporary China, the dimension of the past may also be of use to understanding the present and even in preparing for the future.

In championing New Sinology, we also keep a gimlet eye fixed on China’s politics of becoming. Previously, we have said that Xi Jinping’s New Epoch is a boon for New Sinology, for in today’s China party-state rule works to preserve the core of the cloak-and-dagger Leninist-Stalinist state while its leaders tirelessly repeat Maoist dicta which are amplified by socialist-style neo-liberal policies wedded to cosmetic institutional Confucian conservatism.

As we have noted in the above, this Lesson in New Sinology — ‘Drop Your Pants, the Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’ — is written both to mark 8 August 2018, a decade since the Opening Ceremony of the XXIX Olympiad in Beijing, and in the context of the new round of patriotic indoctrination ordered by the Party on 31 July 2018. To appreciate the ‘Offensive to Promote the Spirit of Patriotic Struggle [that requires intellectuals to] Contribute Positively to Building the Enterprise [of the Party-State and China]’ 弘揚愛國奮鬥精神、建功立業新時代活動, this Lesson consists of five inter-connected essays:

- Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, China Heritage, 8 August 2018

- The Party Empire, China Heritage, 17 August 2018

- Homo Xinensis, China Heritage, 31 August 2018

- Homo Xinensis Ascendant, China Heritage, 16 September 2018

- Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018

***

In the following, we first revisit ‘The Rivers & Mountains’ of the August 2008 Beijing Olympics before going on to consider the ideas and activities of Hu Qiaomu, a writer who worked for Mao Zedong from 1942 to 1969 — he was later an important ideological adviser to Deng Xiaoping. We then use the work of Yang Jiang, a translator and playwright who was teaching at Tsinghua University in the late 1940s — and who happened to know Hu Qiaomu through her husband Qian Zhongshu — to offer an insight into the Thought Reform Campaign that transformed China’s educational system and intellectual life.

Hu Qiaomu reappears in the second part of ‘Drop Your Pants’, with devastating significance, as he played a major role in Chinese politics from the late 1970s up until biological attrition finally removed him from the scene in 1992. In part two we also touch on the playwright and essayist Wu Zuguang (who coincidentally was the editor who first published Mao’s famous poem ‘Snow’, see below), to whose memory we dedicated the translation of Xu Zhangrun’s Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad. In the process we also discuss the tragic figure of Chu Anping and his concept of The Party Empire 黨天下. In the final three instalments in ‘Drop Your Pants’, we introduce Homo Xinensis, the New Socialist Person of Xi Jinping’s New Epoch and offer a preliminary assessment of the phenomenon.

***

Other Lessons in New Sinology:

- Geremie R. Barmé, Living with Xi Dada’s China Making Choices and Cutting Deals (16 December 2016), published in China Heritage, 20 July 2017

- The Editor, Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018

- The Editor and Lee Yee 李怡, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018

- The Editor and Others, It’s Time to Talk About Evening Talks at Yanshan 燕山夜話, China Heritage, 20 July 2018

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待, trans. with notes by Geremie R. Barmé, China Heritage, 1 August 2018

Ruling The Rivers & Mountains

穩坐江山

The Cultural Revolution was launched to ‘ensure that The Rivers and Mountains [of China] resolutely conquered by the proletariat would never change colour’ 保證無產階級鐵打的江山永不變色. China would not abandon the red of revolution for the black of revisionism. It would not fall prey to the kind of weak ideological leadership of the Soviet Union following the death of Stalin. Since 1989, successive Chinese leaders have by their actions supported the Marxist-Leninist legacy of the Mao year; just as significantly, albeit silently, their world view evinces a nostalgia for Stalin. In some respects, Xi Jinping is a twenty-first-century Stalinist.

***

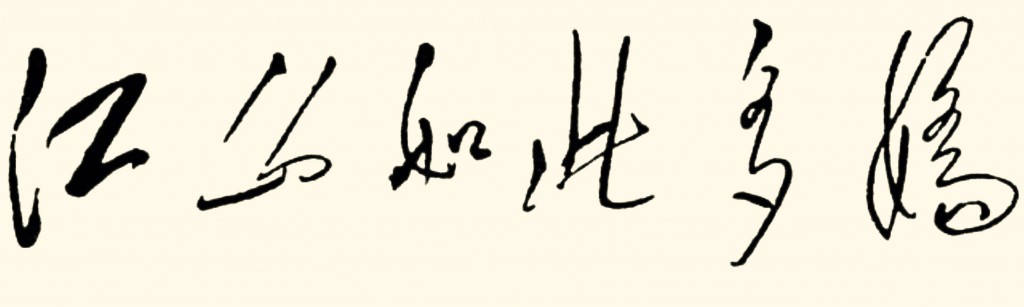

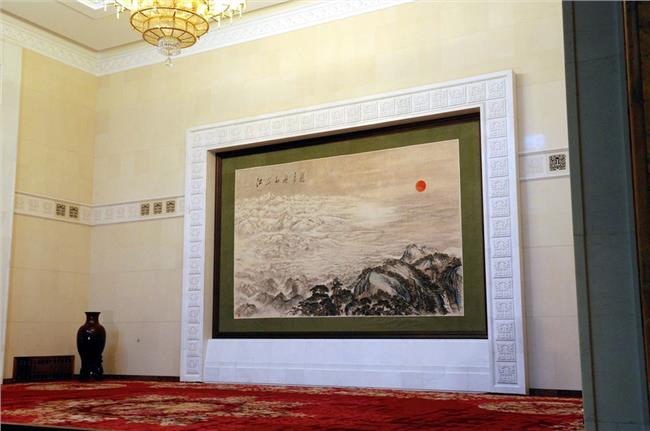

In 2003, the old expression jiāngshān 江山 (also héshān 河山), literally ‘Rivers and Mountains’ was invested with new metaphorical power. In traditional terms it means the political territory of an empire or kingdom, incorporating its landscape — its ‘rivers’ and ‘mountains’. This is different from the culturally inflected expression ‘mountains and waters’ shānshuǐ 山水, the landscape of poetry and painting. Previously, jiāngshān was recast as an enduring political expression by Mao Zedong when he used it in his most famous poem, ‘Snow’ in the 1930s in which he exclaims ‘This land [literally, ‘mountains and rivers’] so rich in beauty’ 江山如此多嬌 (see below).

At around the same time as a controversial pro-democracy TV series Towards a Republic 走向共和 screened in 2003, another multi-part production preached the virtues of one-party rule. Rivers and Mountains 江山 produced by China Central Television was set in the crucial period years 1949-1950, when the Communists first came to power following victory in the civil war. The theme song of the show was sung by an well-known army artiste by the name of Peng Liyuan 彭麗媛, the wife of an upcoming Party leader by the name of Xi Jinping. The song, the singer, and its context, were controversial enough within the Chinese critical world since, given Xi Jinping’s background, and political trajectory, Peng’s performances had an air of the presumptive about them (see, for example, Peng’s 1 August 2007 rendition of the song). In fact, as the factional struggle over Party leadership intensified, it was rumoured that Peng Liyuan was discouraged from singing the song, one which contained such lines as:

Conquering All-Under-Heaven

Ruling The Rivers and Mountains

Wholeheartedly for

The Weal of the Common People

打天下

坐江山

一心為了

老百姓的苦樂酸甜

***

In ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待, published on 24 July 2018, the legal expert Xu Zhangrun pointedly wrote:

You [Communists] ‘Rule the Rivers and Mountains’ [坐江山, a traditional expression that indicates control over the geo-political and civilisational realm of China]; you ‘Gorge Yourselves on the Rivers and Mountains’ [literally, ‘Eat/ consume the Rivers and Mountains’ 吃江山] but, when Your Rivers and Mountains are in trouble [江山有事了], suddenly we’re all expected to pull together and [help you] ‘Protect the Rivers and Mountains’ [保江山] as well as ‘Join as One to Overcome Present Difficulties’ [that have resulted from the trade war]. What utter nonsense! 你們「坐江山」「吃江山」,江山有事了,就讓大家「共克時艱」來「保江山」,這不扯淡嗎!

***

***

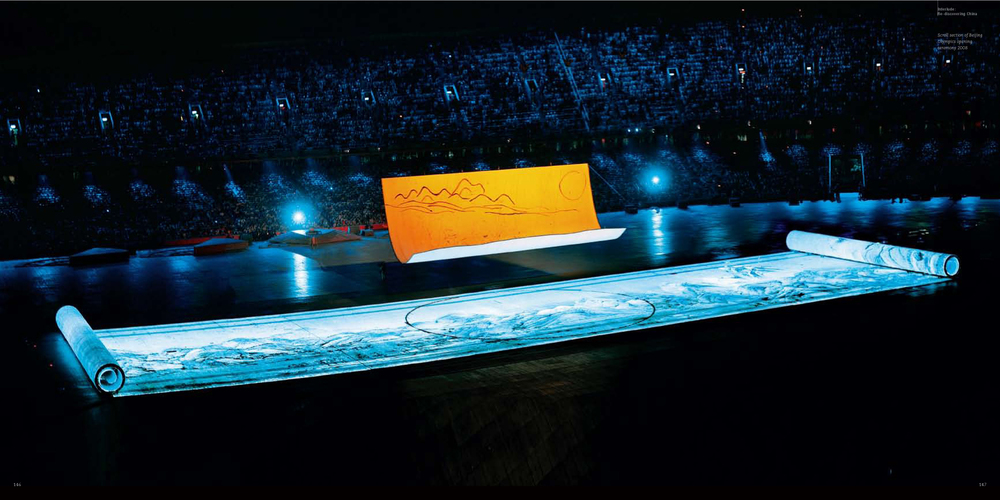

It is worth recalling that The Rivers & Mountains 江山 also notably featured in the 8 August 2008 Beijing Olympic’s opening ceremony. As I observed at the time:

Most observers noted that Mao, the party chairman who founded the People’s Republic in 1949 and led the country until his death in 1976, was absent from Zhang Yimou’s Olympic opening ceremony paean to China’s past civilisation. Of course, they might have missed the pregnant absence of the dead leader in the heavily rewritten ‘Song to the Motherland’ 歌唱祖國. The original of the song featured the dead leader, but he was gone from the version mimed by nine-year-old Lin Miaoke 林妙可 (the real singer was Yang Peiyi 楊沛宜 who rumour held was excluded on the grounds that she was not suitably photogenic by Xi Jinping and his songstress wife Peng Liyuan 彭麗媛). However, in reality, the Great Helmsman did get a look-in, if only obliquely.

On the unfurled paper scroll that features center stage early in the performance, dancers trace out a painting in the ‘xieyi‘ 寫意, or impressionistic, style of traditional Chinese art. Their lithe movements create a vision of mountains and a river to which is added a sun. To my mind, it is an image that evokes the painting-mural that forms a backdrop to the statue of the Chairman in the Mao Memorial Hall in the center of Beijing. That picture, designed by Huang Yongyu 黄永玉, a noted artist persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, is, in turn, inspired by a line from Mao’s most famous poem ‘Snow — to the tune of Qinyuan Chun’ 沁园春・雪 (February 1936) that reads, ‘How splendid the rivers and mountains [of China]’ 江山如此多嬌 (the official translation reads ‘This land so rich in beauty’). The poem lists the prominent rulers of dynastic China and ends by commenting on how all these great men fade in comparison to the true heroes of the modern world: the people. In fact, the poem is generally interpreted as being about Mao himself, the hero of the age 風流人物.

In their opening ceremony design, what Zhang Yimou and his colleagues achieved, be it intentional or not, is a rethinking of this reference. Eventually, the painting is colored in by children with brushes and the sun becomes a jaunty ‘smiley face’. In the remaining blank space of the landscape the athletes of the world track the rainbow of Olympic colors as they take up their positions following their entry to the stadium. Thus, a Chinese landscape, with its coded political references (after all, what does a sun usually mean in modern-style guohua 国画?), is transformed into something that is suffused with a new and embracing meaning by the global community. It offers a positive message for the future of China’s engagement with the world, not only to international audiences, but perhaps also to China’s own leaders, who, apart from Premier Wen Jiabao, for the most part sat stony-faced through the extravaganza. It is also significant that many of the high-points of the opening ceremony were the result of a collective collaboration of designers working closely with Chinese artists who have returned from long years overseas, as well as with British and Japanese creators.

— G.R. Barmé, Painting Over Mao, Notes on the

Inauguration of the Beijing Olympic Games

China Beat, 12 August 2008 (with emendations)

— And, Barmé, China’s Flat Earth, History & 8 August 2008,

The China Quarterly, 197 (March 2009): 64-86

Communist Party Politburo Standing Committee member Xi Jinping had oversight of security and coordinated policy during China’s Olympic moment. Peng Liyuan had previously sung ‘The Rivers & Mountains’ until she was advised that given the delicacy of the politics surrounding the succession she should avoid the song, especially as there was widespread opposition to a member of the Party Gentry like Xi (or for that matter Bo Xilai) being promoted to head the party-state. From 2008 until 2012, the main question for Chinese politics was who would end up in an unassailable position to rule over The Rivers and Mountains of China 穩坐江山?

***

***

Snow

— to the tune of Qinyuan Chun

沁園春 · 雪

North country scene:

A hundred leagues locked in ice,

A thousand leagues of whirling snow.

Both sides of the Great Wall

One single white immensity.

The Yellow River’s swift current

Is stilled from end to end.

The mountains dance like silver snakes

And the highlands charge like wax-hued elephants,

Vying with heaven in stature.

On a fine day, the land,

Clad in white, adorned in red,

Grows more enchanting.

The Rivers and Mountains so rich in beauty

Has made countless heroes bow in homage.

But alas! Qin Shihuang and Han Wudi

Were lacking in literary grace,

And Tang Taizong and Song Taizu

Had little poetry in their souls;

And Genghis Khan,

Proud Son of Heaven for a day,

Knew only shooting eagles, bow outstretched

All are past and gone!

For truly great men

Look to this age alone.

北國風光,

千里冰封,

萬里雪飄。

望長城內外,

惟余莽莽;

大河上下,

頓失滔滔。

山舞銀蛇,

原馳蠟象,

欲與天公試比高。

須晴日,

看紅裝素裹,

分外妖嬈。

江山如此多嬌,

引無數英雄競折腰。

惜秦皇漢武,

略輸文採;

唐宗宋祖,

稍遜風騷。

一代天驕,

成吉思汗,

只識彎弓射大雕。

俱往矣,

數風流人物,

還看今朝。

***

Drop Your Pants, Cut Off that Tail

脫褲子,割尾巴

The Yan’an Rectification was launched following years of factional infighting both over the ideas behind and the strategic practices of revolutionary warfare. Having won an internal Party power struggle to take over the leadership of the Communist Party during the Long March and now settled in the wartime base of Yan’an in Shaanxi province, Mao moved to consolidate his factional victory. He followed the institution rout of this opponents with an ideological purge that would his faction would use to denounce their ideas and enforce a new ideological approach and style of Party management, first on the elite of the Party and then on all of its members.

The campaign, among other things, was an extended attack on ‘dogmatism’ 教條主義, a shorthand used to describe the erroneous thinking of Mao’s foes, men who were, for the most part, Soviet-educated apparatchiki influenced by the Comintern. Under their failed leadership they had disastrously applied the undigested Stalin-inflected Marxist-Leninist theories that they had acquired in the Soviet Union. Their attempts to replicate a worker-based, intellectual-led Russian revolution proved to be woefully unsuited to China’s vast rural realities.

A quick-witted young writer who had studied history and physics at Tsinghua University in Beiping (as Beijing was known from 1928 to 1949) by the name of Hu Qiaomu had recently come to Mao’s attention. Impressed by his writing ability and intellectual agility, Mao would say that the thirty-year-old Hu was a model intellectual, one ‘with the most thoroughly reformed thinking and the most beautiful of souls’ 思想改造得最好、靈魂最美. The non-Party writer and editor Zhu Zheng (朱正, 1931-) later observed that Hu was so enamoured of Mao (and dazzled by his proximity to power) that he devoted his life to being ‘a propagandist for the Communist Party: explaining it and defending it tirelessly.’

As the Rectification Campaign began in earnest in early 1942, Hu Qiaomu drafted an essay titled ‘Dogmas & Pants’ which, after being revised by Mao, was published as a keynote editorial in Liberation Daily, the leading Party paper in Yan’an. Hu employed the metaphors of ‘pants, tails and washing’ to describe the process of revelation, self-criticism and mass denunciation, and exoneration. It was a schema that would be applied throughout the movement, or rectification 整風, one used to force cadres to examine their ideas (and their previous loyalties), confess their ideological shortcomings and subject themselves to the merciless critiques of their comrades.

First, they had to be willing to admit the error of their ways. Then they had to reveal themselves to others in study groups, or to use Hu Qiaomu’s earthy locution, ‘drop their pants’ 脫褲子. Then, as the collective examined their previous statements, political actions, affiliations and ideas, if they were found wanting, or revealed a previously invisible or unacknowledged ‘tail’ 尾巴 of ‘dogmatism’, they would have to lop it off mercilessly 割尾巴 . Only when they were rid of such foreign-inspired ideological excrescences could they join in solidarity with everyone else under investigation 排隊, and frankly confess their limitations to the collective via a process of scarifying ‘washing in public’ 洗澡. Following interrogation, further investigation, the concentrated study of key ideological texts selected by Mao and his cohort, the writing of reports on the status of their thinking and the level of their ideological self-awareness, as well as by accepting with due humility comradely criticism, no matter how harsh, would the cadre in question finally be permitted to rejoin the revolutionary cause.

The process of rectification, which continued well into 1943, resulted in the Mao-ification of the Communist Party and the unassailable status of Mao’s ideas, strategy and language in the Party as a whole, something that would continue, despite numerous attempts to ‘revise’ things, until after the Chairman’s demise in September 1976. Not everyone survived being ‘rectified’, but the resulting discipline contributed not only to the Communist victory in the Civil War of 1946-1949, it would remain an important blueprint for the Party’s internal mechanisms of rule and compliance long into the future.

***

Dogmas & Pants 教條與褲子

Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木

(Excerpts)

Trousers tell us a lot about dogmatism — there’s an organic relationship. If you’re absolutely sincere about opposing dogmatism, then the first thing you have to do is have the determination and courage to drop your pants. That’s the key today.

Let me give you an example. In his speech on the 1 February [1942], Comrade Mao Zedong said that the Party line at the moment is correct. However, there are those Party members who have not corrected the Three Winds. So everyone raises a big hue and cry about cutting off the tail of Subjectivism, Factionalism and Cliched Writing. With one act won’t all the tails be eliminated and the Party complete and perfect? But a tail is not going to fall of just because you say it does. Everyone is scared of dropping their pants because that’s what is concealing those hidden tails. You can only see them when you drop your pants, and you have to cut those tails off with a blade, and you must bleed when you do it. No matter the size of the tail, the size of the blade, or the amount of blood spilled, it’s not going to be a comfortable process, that’s for sure. …#

Some well meaning comrades want to drop their pants alright, but they want to do it in private because they feel if they do it in front of the Masses not only will it be ungainly, the Enemy and Anti-Communists will be standing to one side applauding. But aren’t the Masses the natural and legally empowered judges and examiners of the Party? … Of course, the propaganda outfits of the Enemy will make up many rumours, but that’s what they do: what they declare is black, the Masses know is white, and you don’t need to be afraid that they’ll take things out of context. …

It’s because we are confident that we encourage voluntary Pants Dropping and as we are basically hale and hearty we encourage Pants Dropping. Whatever minor blemishes are found will soon be eliminated. But there are those who lack similar confidence; they always act coy when faced with the Masses who are anxious for them to bare it all. Moreover, once we’ve got rid of the few flaws hidden by our pants, and unabashedly cast them into the place that all waste should go, some people want to gather them up and treat them with great reverence and even absorb them into themselves. Each to his own, but what can we do about that apart from feeling apologetic?

— Editorial, Liberation Daily, 9 March 1942

一九四二年三月九日《解放日報》社論

Note:

- Hu Qiaomu’s use of the metaphor of the concealed tail would have reminded his audience of the beguiling female Fox Spirits 狐狸精 of Chinese folklore. It was believed that these enticing creatures were able to assume human form by means of which they caused mischief and ensnared the lovelorn. Their true identity was often only accidentally revealed by a tail, which they could not disguise. Fox-Spirits feature in Pu Songling’s popular Qing-dynasty collection of Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 蒲松齡著《聊齋誌異》, translations from which appear in Nouvelle Chinoiserie. Hu/Mao employed the reference to hidden tails and exposure intentionally to confront the delicate sensibilities both of their male and female comrades.

Source:

- Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, ‘Dogmas & Pants’ 教條與褲子, 《胡喬木文集 第一卷》, Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1992, pp.48-50

***

Li Rui (李锐, 1917-2019), a Yan’an veteran who was later also one of Mao’s secretaries and a famous critic of the Communist Party in his later years, said that many people in Yan’an were shocked by the crudeness of Hu Qiaomu’s choice of words. Others celebrated this break with the affected prose and generally polite form of expression that, even after the Literary Revolution started in 1917 that had replaced a fusty literary language with the richness of vernacular Chinese, had insinuated itself into the intellectual life of the country. After all, as early as 1927, Mao Zedong had declared that:

A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another. 革命不是請客吃飯,不是做文章,不是繪畫繡花,不能那樣雅致,那樣從容不迫,文質彬彬,那樣溫良恭讓。革命是暴動,是一個階級推翻一個階級的暴烈的行動。

Mao himself often used expletives and vulgarities to convey his message. In his call to expunge ‘Party Stereotyped Writing’ 黨八股 as part of the Rectification of the Three Winds in Yan’an in 1942, he advocated using language that was unadorned and that communicated easily with ordinary people, ‘less singing of empty, abstract tunes’. Despite the immediate, demotic appeal of trash-talk, over the long run the Communist lurch towards the gutter had a profound effect on the country’s political life. It would contribute to the process of dehumanisation that became a central feature of the Communist Party’s class-based politics; it encouraged the popular use of obscenities, abuse and terms related to bestiality that shaped the way people, in particular young people, spoke about their political enemies. Apart from Hu Qiaomu, other important Party thinker-writers would also flourish in Yan’an. They included Deng Liqun (鄧力群, 1915-2015), whose political influence lasted up until his recent death, as well as Chen Boda (陳伯達, 1904-1989), one of the greatest talents behind Mao-era hyperbole. Chen also became one of Mao’s Yan’an-era secretaries; he was a colleague of Hu Qiaomu and a canny writer. His colourful prose and unique style of invective was crystallised in the vituperative cadences of mainstream propaganda. As editor of People’s Daily in the early Cultural Revolution his talents achieved an apogee of sorts and the paper’s editorials, replete with blood-curdling expressions and histrionics, incited Red Guards to ever greater heights of violence.

The spittle-laded abuse and shrill tones used by today’s ‘Patriot-Scoundrels’ 愛國賊, the high dudgeon employed by China’s official spokespeople, as well as the supercilious formulations of The Global Times 環球時報 are part of the abiding linguistic legacy of Mao, Hu, Deng and Chen. Their collective line in abusive and vulgar prose had played a key role in the legitimisation both of intellectual and physical violence from the early 1940s, and both remain central to the way the Communist Party thinks, speaks and acts today. Despite their façade of spiritual civilisation and the keen promotion of conformity and civility, Communist leaders remain, at heart, brawlers and village toughs.

Roll Over! 狗打滾

Old Wu wanted his puppy to roll over on his command, but the dog didn’t respond. Wu demonstrated by rolling on the ground himself. Even when he was covered in dirt the dog remained motionless. A passerby thought the dog was training his master.

老吳畜一小犬,教其打滾不慧,乃現身於地反覆滾之,埃塵滿身而小犬木然於側。客見,以為犬教習。

***

Abandon All Shame

Get in Line and Wash in Public

排隊洗手洗澡

誅心: to get someone to reveal the motivations hidden in the heart, and to achieve one’s aims by manipulating that knowledge. Killing interiority.

***

The pressure of an all-powerful totalitarian state creates an emotional tension in its citizens that determines their acts. When people are divided into ‘loyalists’ and ‘criminals’ a premium is placed on every type of conformist, coward, and hireling; whereas among the ‘criminals’ one finds a singularly high percentage of people who are direct, sincere, and true to themselves. From the social point of view these persons would constitute the best guarantee that the future development of the social organism would be toward good. From the Christian point of view they have no other sin on their conscience save their contempt for Caesar, or their in correct evaluation of his might.

― Czesław Miłosz, The Captive Mind

Czesław Miłosz’s The Captive Mind (1953) was translated into Chinese by Stephen Soong (宋淇, 1919-1996), a good friend of Qian Zhongshu and his wife Yang Jiang (who are introduced below), as 攻心計 (see 斯沃夫· 米沃什的《攻心计》 (1956). Soong was inspired by the ancient line:

攻其身不如攻其心。

It is more effective to conquer

a person’s heart-mind than

to assault them physically.

His translation was eventually also published on the Mainland in 2011, but under the tone-deaf title 《被禁錮的心靈》.

***

In 1950, the playwright and novelist Yang Jiang (楊絳, 1911-2015) was at Tsinghua University. Her husband, the renowned scholar Qian Zhongshu (錢鐘書, 1910-1998) had been instructed by his old university friend Hu Qiaomu (they had both attended Tsinghua) to move into Beijing itself where he was to work on the committee that would produce the English-language version of the first three volumes of Mao Zedong’s Selected Works (he later also participated in the group set up to translate Mao’s poems, including ‘Snow’, which is reproduced above). Qian could visit his wife, but because of his important work he was soon deemed to have been suitably remoulded; his wife, however, had to submit to the ordeal of ‘washing in public’. She would later recall:

We [Yang Jiang and her husband Qian Zhongshu] really were hopeless and simply had no idea. We believed in the old saying ‘It’s Easier to Refashion the Rivers and Mountains than to Get a Person to Change their Ways’. We were astonished to discover that once the ‘Masses were Motivated’ it was as though a switch had been flicked on a robot. Everyone did exactly what was required. People lost all humanity. 我們閉塞頑固,以為‘江山好改,本性難移’,人不能改造。可是我們驚愕地發現,‘發動起來的群眾’,就像通了電的機器人,都隨著按鈕統一行動,都不是個人了。

— 楊絳《我們仨》,三聯書店,2003年

The Thought Reform Movement was the first occasion after the founding of the People’s Republic when the educated and professional population as a whole was required actively to ‘remould’ their thinking. Once suitably reformed, they would be better attuned to the needs of the party-state and its ideological directives; a politically correct attitude would presumably also liberate the society’s productive forces. The process started, naturally enough, in universities, publishing houses, and cultural institutions. A new and, for many, disturbing political vocabulary was introduced along with the movement. Everyone with an education was automatically under suspicion, and they were required to renounce publicly the errors of the past; they had to be ‘washed’ clean before they could he accepted into the new society.

University academics would be required to line up and, depending on the severity of their issues they would be divided into groups to wash 排隊洗澡:

- In a large bath tub 大盆 — if they had to make their self-criticism in front of the students and staff of the whole university;

- In a medium-sided tub 中盆 — if their critique only had to be made inside their own department; or,

- In a small hand basin 小盆 — if their remarks could be made in a small study session.

Preparations were made by motivational meetings 控訴醖釀會 where students and general staff with grievances were encouraged to speak out against teachers and professors formerly in positions of authority and power. Materials about the activities of the individuals concerned were then collected so that the Party committee could ascertain what reactionary ideas the teachers had spread in their classes and interactions and what kind of decadent or depraved lifestyle they had. The individual under investigation was then informed of the case against them and required to write a detailed examination or draft speech which was then used as a model for others to listen to and appraise. After making one’s case at a mass meeting, the audience would be invited to critique the penitent’s performance, style, presentation and attitude. Depending on all of these and public sentiment, the individual might be allowed to ‘Go Through the Pass’ 過關 and start a new life of service to the Party and the state. If their self-scarification failed to convince, seemed insincere or lacked depth, they would be required to rewrite their script and repeat the performance until the Masses and the Party Committee were satisfied. At any stage size of the ‘bath’ might be increased. For those who put up a show of resistance, there were repeated mass struggle sessions and denunciations which would continue until they surrendered and recognised to the wisdom of the People.

Discussing how best to deal with the most obstinate cases, the head of the Ministry of Education said:

Make sure the water is hot enough to scald some people, just try not to burn them to death.

— 董渭川:「談高等學校中的黨群關係」,

原載《九三學社師大區支社整風資料〈七〉》

***

In her 1988 novel, Washing in Public 洗澡 (also translated as Baptism), the translator and playwright Yang Jiang created a witty love story that is played out against the back-drop of this period of social upheaval. It contains a fictional reconstruction of the kind of denunciation and reform of intellectuals that was carried out throughout China in the early 1950s.

To illustrate the process by which intellectuals, university professors, writers and editors were inducted into their accommodation with the rule of socialism in China, it is instructive to follow Yang Jiang’s recreation of the process of ‘Washing in Public’. A mobilisation speech by the Party boss of a fictional literary research institute [at the time, both Yang and Qian were teachers at Tsinghua University] is followed by the self-criticism of an old scholar. The catechism of public self-flagellation has not yet been entirely formalised, so the old scholar, Ding Baogui, finds it difficult to strike the right note. The appeal of the Party Secretary, Fan Fan, to the intellectuals in his institute seems to come straight from the heart, but the carefully balanced mixture of accusation with cajolery and sincerity in such statements was closely scripted and repeated in countless meetings by cadres and activists throughout the country as the process of thought reform unfolded. Fan Fan tells the assembled intellectuals that

New China has embraced intellectuals from the old society in the hope that you will work hard at reforming yourselves and make a real contribution to the people. However, I have little doubt that everyone is ashamed of their achievements over the past two years [that is, from 1949]. Nothing much has been produced in terms either of quality or quantity, yet plenty of mistakes have been made. This is because we’re still burdened by the feudal and bourgeois thinking of the past. It constricts our productive capacity and limits our ability to work effectively to achieve the tasks in hand. Everyone is so undisciplined that they are making no progress whatsoever. We must cast off our burdens and move forward.

First of all, we should examine the ideological baggage that is weighing us down and see whether there are great treasures inside or just rubbish. Old thinking and dated ideology are still deeply embedded in the minds of some comrades. Now it’s not like some bundle that you carry around on your back and can discard at Will. It’s more like ingrained filth in the skin; it won’t come off without lots of water and hard scrubbing. You could also compare it to a festering sore, or a concealed tail. Neither can be eliminated without an operation. First and foremost, we mustn’t be shy about exposing our ugliness; we must show everyone just what filthy, shameful things we have inside us. Secondly, we mustn’t worry about the pain involved in scouring off the filth, gouging out the sore, or cutting off that tail.

This is absolutely necessary. But we insist that you do it consciously and voluntarily. Self-remolding is an act that demonstrates a responsible attitude toward the society; no one can force you into it. Only when an individual has the correct attitude, only when they really want to remould themselves, can the masses offer them help. If you don’t think you need it, if you insist on hiding your festering sores from view then even though others might smell the fetid stench, there’s little they can do to help you. That’s why it’s important for everyone to have the correct attitude.

The next mass rally is held in the university conference hall. The amassed young people of the institute are solemn, their faces expressionless. Clearly, they have already corrected their attitudes and taken a firm stand. Ding Baogui feels a marked change in the atmosphere when he enters the hall; it’s as though he no longer knows any of his younger colleagues — even the pleasant ones act like strangers. Ding feels as though Fan Fan’s comments at the previous meeting had been directed specifically at him; it is as though he can already feel the knife at his back.

Thereafter, all the men and women who have been identified as bourgeois intellectuals obediently attend the daily model report sessions, listening carefully not only to the self-criticisms but also to evaluations the masses make of the critiques. The comments are all very pointed, much ‘help’ is given, and approval is hard won. On a number of occasions the masses scream angry denunciations at people they deem to be ‘stubbornly resisting reform’. Such scenes make the bourgeois intellectuals feel threatened and scared.

At home Ding Baogui sighed constantly, and remarked to his wife, ‘Now I know that the uglier you are the more beautiful, the smellier the more fragrant. What has someone like me got to confess? The more evil a person has done the less they care about face, they have a lot of material for their self-criticisms, they’re convincing and detailed. They appear to have a high degree of political awareness, and their confessions are penetrating. But it’s not all smooth sailing; if you leave anything out the masses jump on you for being insincere, sly, and superficial. On the other hand, if you give them everything they want in one go, you have nothing more to cough up when they put on the squeeze. Then what?’

Gradually it dawns on Ding that the key to succeeding in the process is self-abasement, you have to treat yourself as your own worst enemy, admit all conceivable errors, and vilify yourself, the more viciously the better. The Party leaders and the masses measure your sincerity by how critical you are of your own faults; you prove the profundity of your self-criticism through the severity of your self-obloquy. The trick is to excoriate yourself mercilessly, while being careful not to insult the intelligence of the masses. Ding realises that to make a successful self-criticism he has to abandon all sense of shame. First he admits to his audience that he originally had numerous reservations about the process — in fact, he’d been terrified:

I was like a girl of good family who would rather hang herself than drop her pants in front of a crowd. But gradually I’ve come around. If you have a tail and you have to have it operated on, you have no choice but to drop your pants, do you? You can’t hide it forever. Anyway, you’d still have to face your groom on your wedding night. Just as such a young woman would want to get married, I want to join the ranks of the people. Until you’re married you’ll never be able to settle down.

It sounds like he is being facetious, but he wears such a pained expression and has such a terrified look in his eyes that it is obvious that he is serious. Everyone waits for what would come next.

It’s impossible to express the full extent of my gratitude to the party. Let me just say a few words about my situation before and after liberation [that is, 1949]. In the past … you needed a foreign degree even to teach Chinese. Despite my age and all the years I’d spent as an impoverished scholar, I couldn’t hope to be made a full professor because I didn’t have a foreign degree and I certainly wasn’t famous. After liberation, however, I was made a full-time research fellow, the equivalent of a professor. What possible reason could I have to complain? I’ve also heard that in the future they’ll do away with yearly contracts; I’ll join the ranks of the people, and like a girl joining her husband’s family, I’ll have job security for life. How could I be anything but thrilled? People who live on a fixed wage like me have two main worries: unemployment and illness. But I don’t have to be afraid any more. I have security, and if I fall ill the public health system will cover my treatment. Of course I support socialism wholeheartedly! …

But I’ve never felt that I’m one of the masters of new China. The old saying goes, ‘Everyone is responsible for the welfare of the state.’ I’m more realistic, however. No, no, I don’t mean realistic. What I mean is, well, it’s just that I don’t feel in control. I don’t feel any sense of social responsibility at all. Who has ever discussed matters of state with me? Who the hell am I anyway? All I can say is that ‘everything’s decided by the meat-eaters” [that is, the ruling class]. Take the War to Resist American Aggression and Support Korea, for example. I got upset just thinking about it: after all these years of war, people were thoroughly sick of any more fighting. Surely We should give it a rest. We’d just had a chance to settle down and here we were, rushing out to fight again. Could we possibly beat the Americans? The facts have proved that my concerns were unfounded. Victory is ours. I have nothing but admiration for the Communist Party. But I have to admit I still don’t feel like one of the masters of the country. I can only hope to be a good citizen, respond to the calls of the Party and obey its orders.

Ding sits down and looks around, rather stunned. He feels as though he is sinking, and that only his head still remains above water. He nervously tells the chairman of the meeting that is all he has to say, but ‘of course, there’s lots of other crimes which I haven’t accounted for yet. Anyway, I’ll admit everything and promise to reform. I only wake up to things slowly, but I’ll come around eventually.’ Thereupon the chairman makes his concluding remarks:

Mr. Ding’s self-criticism is characterised by a single emotion: fear. It reveals the distance that remains between him and the Party and the People. He’s scared of the party, scared that we’re going to criticise him. It wasn’t a crime to attack the Party before liberation! The Party can’t be overthrown by criticism. Since liberation your feelings about the party have changed, and you’ve shown that you’re not such a diehard. Your concern for the nation and the people shows that you do have some sense of responsibility. But you act as though the party thinks of you as an old enemy. You should really do something about your attitude. You must learn to rely on the party and the people. … You too, after all, are one of the People, but you are still determined to see yourself as being in opposition to the masses — that’s why you’re hesitant and scared. You think the people are a fearful enemy: you believe the Party and the People are bent on making things difficult for you. Don’t be afraid, Mr Ding. Political movements are a way for you to transform yourself. Through them you can join the ranks of the People. We welcome everyone who is willing to join us. We want to unite with all forces that can be united with, work hard together, and make our collective contribution.

A final round of applause signals that Ding Baogui’s self-criticism has been accepted. He is tremendously relieved. and he is so overcome with emotion that he nearly bursts into tears with relief and joy. Ding feels like he came first in the imperial exams. It is as though he had woken from a nightmare and after the meeting he walks home as if floating on air.

— adapted from G.R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile (2004)

***

Aesthetic Ketman

In this latest era of untruth, Miłosz’s description of ‘Ketman’ (or kitmān in Persian), describes a form of double-think that allows the individual to retain their own ideas while expressing the opposite in public.

— The Editor

In these conditions, aesthetic Ketman has every possibility of spreading. It is expressed in that unconscious longing for strangeness which is channeled toward controlled amusements like theater, film, and folk festivals, but also into various forms of escapism. Writers burrow into ancient texts, comment on and re-edit ancient authors. They write children’s books so that their fancy may have slightly freer play. Many choose university careers because research into literary history offers a safe pretext for plunging into the past and for converse with works of great aesthetic value. The number of translators of former prose and poetry multiplies. Painters seek an outlet for their interests in illustrations for children’s books, where the choice of gaudy colors can be justified by an appeal to the naive imaginations of children. Stage managers, doing their duty by presenting bad contemporary works, endeavor to introduce into their repertoires the plays of Lope de Vega or Shakespeare — that is, those of their plays that are approved by the Center.

— Czesław Miłosz, The Captive Mind (1953), p.64ff

References:

- 盛禹九, 複雜多面的胡喬木——同李銳談話錄, 《炎黄春秋》, 2014年第2期

- 李楊, 建國後第一次思想改造運動的前前後後, 《中國社會導刊》, 2004年第11期, posted online on 5 August 2012

- Geremie R. Barmé, China’s Flat Earth, History & 8 August 2008, The China Quarterly, 197 (March 2009): 64-86

- Geremie R. Barmé, For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone — Watching China Watching (XII), China Heritage, 27 January 2018

- Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, ‘Dogmas & Pants’ 教條與褲子, 《胡喬木文集 第一卷》, Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1992, pp.48-50