Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance (VIII)

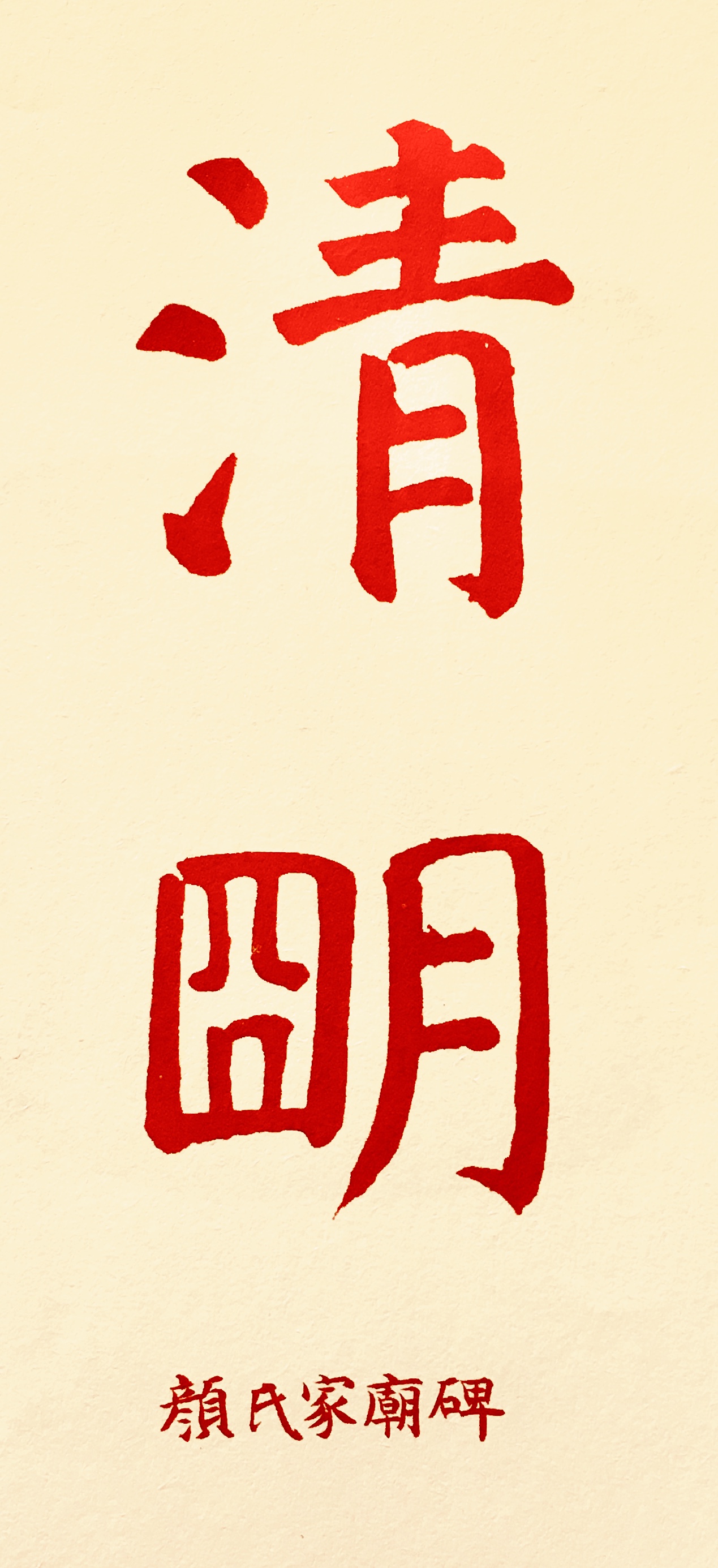

The 5th of April 2019 marks the annual Qingming Festival 清明節, when departed loved ones are remembered and forebears are respectfully celebrated.

The Qingming Festival of 2019 offers a moment to recall some of the great figures of the Chinese past who protested against misguided politics, injustice and popular folly. A few days before this Qingming, the writer Tao Haisu 陶海粟 circulated online three poems in the classical style to express his support for Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 of Tsinghua University. Below, following a short introductory essay on protest and poetry in the People’s Republic, we reproduce Tao’s poetic trinity and offer draft translations with some rudimentary notes that may help readers better understand both their humour and their significance.

These poems evoke a Muse with split loyalties: both to traditional verse as well as to the more humorous tradition of doggerel rhyme 打油詩 dǎyóu shī, itself a venerable and more light-hearted poetic strain the origins of which can be traced back to the Tang dynasty.

From my late twenties, I frequently acted as a ‘poetry mule’ when Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, Huang Miaozi 黃苗子, Wu Zuguang 吳祖光, and sometimes other aficionados from the old Layabouts’ Lodge 二流堂, exchanged doggerel verse that made light of the portentous events of the day. No one had ready access to a telephone and, although the Beijing postal service was efficient, my elders enjoyed having an eager, bike-riding ‘foreign friend’ hand deliver their slightly subversive four-liners in person, collect updates and deliver good-humoured ripostes. It was part of an ancient tradition among men and women of letters; it was also, in more ways than one, an education.

***

Here we would note that the Letter of Support composed by graduates of Tsinghua University and translated in our series ‘Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University’ (see ‘Speaking Up for a Man Who Dared to Speak Out’, China Heritage, 1 April, 2019) quotes the most famous line in an encomium that Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 wrote for Wang Guowei 王國維 in 1930 where Chen praised Wang for being possessed of ‘A Spirit Unfettered and a Mind Independent’ 獨立之精神, 自由之思想. This is also used by Guo Yuhua in the conclusion to the essay she wrote in support of Xu (see Guo Yuhua 郭於華, ‘J’accuse, Tsinghua University!’, China Heritage, 27 March 2019).

Wang was one of the last great scholars of classical Chinese poetry, in particular the ci-lyric 詞 and, decades later, it would turn out that Chen Yinque employed his mastery of classical verse to comment on the Mao era. In a breathtaking work of scholarship Yu Yingshi 余英時 analysed the poems Chen wrote before his death in October 1969, revealing the blind historian’s undaunted spirit. As a result of Yu’s forensic analysis, it was revealed that Chen had chosen the most powerful Chinese literary form to reject Mao, his comrades and their deadly enterprise. Hu Qiaomu, the Party ideologue whose machinations have often featured in China Heritage was aghast at this development. Thinking of himself as a ‘friend of prominent intellectuals’, and believing that a few hours of conversation with Chen Yinque decades earlier gave him some privileged insight into the psychology of the great scholar, Hu organised a Hong Kong-based denunciation of Yu Yingshi’s findings. The results were clumsy, but in keeping with in the trademark style of Party propaganda, and Yu made a point of joking about the episode in his introduction to the second edition of the book he devoted to his study of Chen’s late poetry.

This is the latest in our series of Lessons in New Sinology. These are works both that offer the general reader some insight into a certain aspect of contemporary China, while also providing students and scholars who are interested in the complex interconnection between that country’s politics, culture, history and thought annotated material that highlights vital aspects of how traditions persist, are re-invented and flourish in new ways.

My thanks to Warren Sun 孫萬國, a dear friend who has a profound understanding of Chinese politics, letters and history, for his suggestions.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

First Day of the Third Month of the

Jihai Year of the Pig, 2019

己亥豬年三月初一清明節

5 April 2019

***

Further Reading:

- The Editor, ‘In the Shade 庇蔭’, China Heritage, 4 April 2017

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018

- 余英時, 《陳寅恪晚年詩文釋證》, based on a series of essays that were initially published in the early 1980s by Ming Pao Monthly 明報月刊 in Hong Kong including: 《陳寅恪的學術精神和晚年心境》、《陳寅恪晚年詩文釋證》、《陳寅恪晚年心境新證》

- Stephen Owen, An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, New York: W.W. Norton, 1996, for the translations of Gong Zizhen’s poems

- John Minford and Joseph M. Lau, eds, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000, for Herbert Giles on Bo Juyi and Donald Holzman on Ruan Ji

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘A Case of Mistaken Identity: Gong Xiaogong and the Sacking of the Garden of Perfect Brightness’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 8 (December 2006)

- The Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

***

Guarding Over Original Intentions

On Qingming each year, it is all too often the case in the People’s Republic of China, that families not only remember their ancestors and forbears, they also grieve anew over loved ones who died in one of the numerous deadly political campaigns launched by the Communist Party since 1949.

On Qingming 2019, as the media reverentially reported that Xi Jinping, the ‘People’s Leader’, was lavishly extolled for remembering Party martyrs, families whose loved ones were killed by the People’s Liberation Army and the authorities on the 4th of June 1989 or during the subsequent crackdown in Beijing and other Chinese cities had no choice but to mourn in secret. Members of Falungong also remembered the coreligionists who have died since the 1999 purge of their sect.

Loyal Party members and soldiers are commemorated by the state on Qingming and the new official Martyr’s Festival 烈士節 for, long after their service and sacrifice in life, in death they have no choice but to maintain their contribution to the Party’s cause forever.

Unquiet Graves

Qingming also marks a significant day when mourners gathered en masse to protest against Party autocracy.

Premier Zhou Enlai had died in January [1976]. On April 5, China’s traditional festival for cleaning graves, two hundred thousand people demonstrated in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Ostensibly mourning Zhou Enlai, the demonstrators were in fact protesting the power of Jiang Qing and her associates. When the crowd refused to disperse at the end of the day, the scene grew ugly — a mob smashed several vehicles and burned a police command post. At night, militia and public security forces, under the control of Hua Guofeng, cleared the square [according to Warren Sun, later testimony and research indicates that, in fact, Hua ‘did not have blood on his hands’ and others were culpable for the murders. — Ed.]. Many demonstrators were beaten — others were arrested. The following morning, the Party Political Bureau declared the incident to be ‘counterrevolutionary’ and removed Deng Xiaoping from all offices as its ultimate instigator. At the same time Hua Guofeng was appointed premier and vice-chairman of the Party.

But after Mao died in September and the ‘Gang of Four’ was arrested in October, China’s politics moved slowly but steadily to the right. As figures disgraced during the Cultural Revolution regained respectability and influence, support for Deng Xiaoping mounted… .

Deng Xiaoping’s victory in this struggle was tied to the Party’s judgment of the 1976 Tiananmen incident. Deng pressed relentlessly for a reversal of the Party’s verdict, arguing that the demonstration in fact had been ‘revolutionary’. By implication, anyone involved in its suppression had committed a grave error. A reversal would be a fatal blow to the authority of Hua Guofeng, former minister of public security.

Many of the 1976 demonstrators had written poems that they posted in Tiananmen Square. Students from Beijing’s Number Two Foreign Language Institute, a school with close ties to Deng Xiaoping, edited over one thousand of these poems and published them in four unofficial mimeographed editions. These began to circulate shortly after the fall of the ‘Gang of Four’, constituting an open provocation to Hua Guofeng. Police from the public security forces searched for some of the pseudonymous or anonymous authors, but not very effectively. In some cases the police revealed the poets’ identities not to Hua Guofeng but to the student editors.

— Richard Kraus, Brushes with Power, 1991

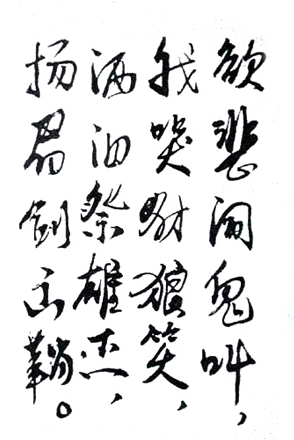

In the days following the Tiananmen Incident on Qingming in 1976, the Party media felt so emboldened by the successful, if bloody, repression of protesters and the ouster of Deng Xiaoping, that it quoted verbatim some of the anti-Mao slogans chanted by the demonstrators, such as ‘The age of the Qin Emperor is over!’ 秦始皇的時代已經過去了. They even published the most famous protest poem, the calligraphic version of which is featured in the above:

In my grief I hear demons shriek;

I weep while wolves and jackals laugh.

Though tears I shed to mourn a hero,

With head raised high, I draw my sword.

欲悲聞鬼叫,

我哭豺狼笑。

灑淚祭雄傑,

揚眉劍出鞘。

Where Silence Reigns

As we noted in the introduction to Xu Zhangrun’s further challenge to the Chinese authorities (see ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018):

In November 1978, Beijing audiences flocked to ‘Where Silence Reigns’ 於無聲處, a play first staged in Shanghai that addressed the question of the repression of the ‘Tiananmen Incident’ two years earlier. Over a number days in early April 1976, crowds had gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn the recently dead Premier Zhou Enlai, and to protest against Mao and his radical supporters. By 1978, the protests were seen in a new light and China itself was undergoing a profound political and economic realignment.

The title of the play — ‘Where Silence Reigns’ — was inspired by a line in a classical Chinese poem by the country’s most famous modern writer, Lu Xun (魯迅, 1881-1936). The last line of the untitled poem 無題, dated 30 May 1934, read 於無聲處聽驚雷, literally, ‘A startling clap of thunder is heard where silence reigns’. In other words: ‘a sudden sound breaks through the oppressive atmosphere’. Lu Xun’s poem was a terse reflection of the seemingly hopeless state of China at the time but the famous last line extolled the promise of unexpected protest. Decades later, both Mao and his enemies — in particular disillusioned Red Guards — would quote the poem to affirm their claims about rebellion against repression and their hopes for a better future.

‘Where Silence Reigns’ was staged at a momentous time in China’s modern history, a period that was remembered and commemorated in many ways forty years later in November-December 2018.

Mao was dead, his radical revolutionary supporters had been arrested or sidelined, essential reforms of education and science were unfolding, men and women who had for decades been jailed, exiled or who were still living in the shadows were being exonerated, and the long-stagnant intellectual and cultural life of the country were going through something of a ‘Beijing Spring’. The Party, the leaders of which were mired in the blood and violence of their misrule, was desperate to regain a measure of legitimacy and to do so quickly. It rejected two decades of a destructive policy that favoured pitiless class struggle and universal ideological repression, and turned its focus to rebuilding a crippled economy and improving the livelihoods of a people that it had cruelly betrayed.

Silence or voicelessness, 無聲 wúshēng, was a theme of Lu Xun’s work, just as speaking out and being heard have been paramount concerns for Chinese men and women of conscience for the last forty years (as well as, when possible, the thirty years before that). In late July 2018, Xu Zhangrun (許章潤, 1962-), a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing and a research fellow with the Unirule Institute of Economics, broke the silence that has spread under the draconian rule of Xi Jinping, the supreme party-state-army leader of the People’s Republic. In an eloquent and withering essay Professor Xu expressed his concerns about the state of Chinese politics and anxiety about the country’s future. (See Xu Zhangrun, ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待, China Heritage, 1 August 2018). Among other things, Xu’s essay warned against the revived spirit of Qin Shihuang, the despotic First Emperor of the Qin dynasty who was so admired by Mao.

Another Repentance

又懺心一首

Gong Zizhen

龔自珍

佛言劫火遇皆銷,

何物千年怒若潮。

經濟文章磨白晝,

幽光狂慧復中宵。

來何洶湧須揮劍,

去尚纏綿可付簫。

心藥心靈總心病,

寓言決欲就燈燒。

Buddhists tell of kalpa fires

dissolving all when they come—

what is it endures a thousand years,

raging like tidal bore?

I have ground away the light of day

in writings to save the state,

dark insights and mad ingenuities

recur in midnight hours.

They surge in me like a boiling flood,

needing a sword’s blow to sever;

once gone, they are tangled in thought,

consigned to the flute of poetry.

Heart’s medicine, heart’s native wit

are both the heart’s disease:

I am resolved to burn in the lamp

these words of parable.

— trans. Stephen Owen

***

‘Another Repentance’ was written by Gong Zizhen (龔自珍, 1892-1841) in 1839. Frustrated with bureaucratic life and as a result of his failure to find support for his ideas, Gong quit officialdom and returned to his native home. The poems he wrote at the time reflect his frustrations and are one of the last expressions of cultural exasperation by a significant man of letters prior to a military conflagration that contributed significantly to the profound changes the Chinese Qing Empire was experiencing. It was the eve of the First Opium War, a conflict between the Qing and the expansive Western trading powers of Great Britain and France. In the aftermath of defeat, China would enter what some would call its ‘long nineteenth century’, one that the Communist Party claims only ended with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

For others, like Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 of Tsinghua University, the long nineteenth century was one during which the Qing Empire not only suffered repeated military and domestic humiliations but also launched a vast enterprise of change. After more than one-hundred and fifty years that modernising transformation of the nation is far from over.

In a series of polemical essays, starting with an appeal in 2016 to preserve the policies of economic transformation and relative openness that underpinned the nation’s life from 1978, Xu Zhangrun became increasingly vocal, and more pointed, in his protests against the political and economic changes that were taking place under the rule of Xi Jinping, Wang Qishan and their Politburo colleagues. When Xi was granted the equivalent of ‘terminal tenure’ as China’s leader in March 2018, a widespread concern in the nation found voluble expression in Xu’s now-famous Jeremiad, ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待 (translated in China Heritage, 1 August 2018).

— GRB

Three Poems for Xu Zhangrun

Tao Haisu 陶海粟

The Chinese Poems:

詩三首

之一

立論不憂和者寡,

著文豈為稻梁謀。

千人諾諾爭弘道,

一士錚錚排逆流。

之二

杜甫小詩譏酷吏,

樂天長卷諷明皇。

當年若是封刪去,

千載唏噓失玉章。

之三

九州遍地多英俊,

萬馬齊喑甚可哀。

屈賈阮白皆杜口,

枉勞天帝降人才。

— 陶海粟 2019-04-02

A Bilingual Text:

詩三首

之一

立論不憂和者寡,

著文豈為稻梁謀。

千人諾諾爭弘道,

一士錚錚排逆流。

Advance lonely argument without concern for concord,

In such writing what paltry profit would one seek?

Well may the slavish mob vie, cleaving to orthodoxy,

One decent man’s steely resolve does go against that tide.

之二

杜甫小詩譏酷吏,

樂天長卷諷明皇。

當年若是封刪去,

千載唏噓失玉章。

In short verse did Du Fu decry cruel officials,

While Letian’s ballad would chide an emperor.

If these, too, had been thus obliterated,

All down the ages would mourn the loss.

之三

九州遍地多英俊,

萬馬齊喑甚可哀。

屈賈阮白皆杜口,

枉勞天帝降人才。

The Nine Regions may seem replete with Heroes,

Heart-breaking, then, that countless steeds fall quiet.

Qu Yuan, Jia Yi, Ruan Ji and Bo Juyi — if they too were silenced,

In vain was the Lord of Heaven’s gift of talents.

— Tao Haisu, 2 April 2019

trans. G.R. Barmé

The Bilingual Text with Notes:

詩三首

之一

立論不憂和者寡,

著文豈為稻梁謀。

千人諾諾爭弘道,

一士錚錚排逆流。

Advance lonely argument without concern for concord,

In such writing what paltry profit would one seek?

Well may the slavish mob vie, cleaving to orthodoxy,

One decent man’s steely resolve does go against that tide.

和者寡 hè zhě guǎ: literally, ‘few can appreciate/ join in/ respond [to Xu Zhangrun’s challenging ideas and literary style]’. This is a reference to the common expression 曲高和寡 qǔ gāo hè guǎ, ‘a tune so refined that others find it hard to sing’

為稻梁謀 wèi dàoliáng móu: literally, ‘to pursue something for the sake of grain’. Although this image comes from ancient poetry, where it refers to how birds are constantly searching for food, here it is a reference to a famous line by Gong Zizhen:

避席畏聞文字獄,著書都為稻粱謀。

I flee the scene, fearing talk of literary persecutions,

My works I write merely to eke out a meagre living.

[That is, I write just to get by, not as a form of protest,

for I fear offending the authorities.]

— 龚自珍,《詠史 · 金粉東南十五州》

千人 … 一士 qiān rén … yī shì: ‘the multitude’ contrasted with ‘one brave man’ or a ‘decent man’. See the following note for more

諾諾 nuònuò: to be obsequious, compliant or fawning. The expression has two famous uses in relation to pre-Qin historical figures:

1. In Sima Qian’s ‘Biography of Lord Shang’ 《史記 · 商君列傳第八》 it says:

The refusal of one decent man outweighs

the acquiescence of the multitude

千人之諾諾,不如一士之諤諤。

This line is also used by Simon Leys as the untranslated epigraph of The Chairman’s New Clothes, his 1971 exposé of the Cultural Revolution. See One Decent Man, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018. The context of the line in Sima Qian is: 趙良曰: 千羊之皮, 不如一狐之腋; 千人之諾諾, 不如一士之諤諤。武王諤諤以昌,殷紂墨墨以亡; and,

2. Han Fei 韩非, one of the thinkers whose ideas lurked behind the Qin autocracy, warned against sycophants:

A person who is already offering obedience before an order is given;

Some one who utters their compliance before a task is assigned.

Constantly examining their master’s countenance to gauge their wishes.

此人主未命而唯唯,未使而諾諾,先意承旨,觀貌察色以先主心者也。

— from ‘Eight Kinds of Treachery’ in Hanfeizi 韓非子 · 八奸

This is the origin of the common modern expression 唯唯諾諾 wěiwěi nuònuò, ‘servile compliance’

弘道 hóng dào: originally meaning to ‘enlarge the Way’ or ‘promote the correct path’, from The Analects 論語:

The Master said: “Man can enlarge the Way.

It is not the Way that enlarges man.”

子曰:人能弘道,非道弘人。

— The Analects of Confucius

trans. and notes by Simon Leys

New York: W.W. Norton, 1997, p.77

《論語 · 衛靈公》

Here 弘道 hóng dào reflects no such grand purpose; the poet employs the expression hyperbolically to refer to the Communist Party line

錚錚 zhēng zhēng: an onomatopoeic expression indicating the sound of clanging metal. It means a person of unyielding strength or moral probity. It is commonly used in the expression 錚錚鐵骨 zhēng zhēng tiě gǔ, ‘adamantine will’ or ‘unbending resolve’, regarded as being a ‘key traditional virtue’, even by the Communists

之二

杜甫小詩譏酷吏,

樂天長卷諷明皇。

當年若是封刪去,

千載唏噓失玉章。

In short verse did Du Fu decry cruel officials,

While Letian’s ballad would chide an emperor.

If these, too, had been thus eradicated,

All down the ages would mourn the loss.

杜甫小詩譏酷吏 Dù Fǔ xiǎo shī jī kù lì: Du Fu (杜甫, 712-770 CE) is one of the greatest poets of the Tang dynasty. As the translator Burton Watson says:

‘His greatest works are at once a lament upon the appalling sorrow that he saw around him, and a reproach to those who, through folly or ignorance, were to some degree responsible for the creation of such misery.’

樂天長卷 Lètiān cháng juàn: Letian is the ‘style’ or courtesy name 字 zì of Bo Juyi (白居易, 772-846 CE), a Tang-dynasty poet also known as ‘Bai Juyi’. 長卷 cháng juàn, or ‘long scroll’, refers to Bo’s most famous narrative work, 《長恨歌》 Cháng hèn gē, composed in 806 CE and translated by Herbert Giles as ‘The Everlasting Wrong’

諷明皇 fěng Míng huáng: ‘admonish the Brilliant Emperor’, that is Emperor Xuanzong 玄宗 of the Tang, Li Longji (李隆基, 685-762 CE). Giles summarises Bo Juyi’s ballad in the following way:

‘It refers to the ignominious downfall of the Emperor Xuanzong, who had surrounded himself by a Brilliant Court, welcoming such men as Li Bo [李白], at first for their talents alone, but afterwards for their readiness to participate in scenes of revelry and dissipation, provided for the amusement of the Imperial Concubine, the ever-famous Yang Guifei [楊貴妃]. Gradually, the Emperor left off concerning himself with affairs of state; a serious rebellion broke out, and his Majesty sought safety in Sichuan, returning only after having abdicated in favour of his son. The poem describes the rise of Yang Guifei, her tragic fate at the hands of the soldiery, and her subsequent communication with her heartbroken lover from the world of shadows beyond the grave.’

封刪 fēng shān: 封殺 fēngshā and 刪除 shānchú banned, deleted, expurgated, etc, essential vocabulary in modern-day China

唏噓 xī xū: to regret, wail or sob in despair. This appears in the modern expression 不勝唏噓 bù shēng xī xū, ‘endless sorrow’ or ‘boundless regret’

玉章 yù zhāng: a general reference to poetic works, or celebrated verse. It can also refer to the classic Book of Odes 詩經 Shī jīng

之三

九州遍地多英俊,

萬馬齊喑甚可哀。

屈賈阮白皆杜口,

枉勞天帝降人才。

The Nine Regions may seem replete with Heroes,

Heart-breaking, then, that countless steeds fall quiet.

Qu Yuan, Jia Yi, Ruan Ji and Bo Juyi — if they too were silenced,

In vain was the Lord of Heaven’s gift of talents.

The third poem is a reworking of Gong Zizhen’s most famous verse, in ‘Miscellaneous Poems of the Year Jihai’ [1839]:

九州生氣恃風雷,

萬馬齊喑究可哀。

我勸天公重抖擻,

不拘一格降人才。

All life in China’s nine regions

depends on the thundering storm,

thousands of horses all struck dumb

is deplorable indeed.

I urge the Lord of Heaven

to shake us up again

and grant us human talent

not bound to a single kind

— 龔自珍, 《己亥雜詩》

trans. Stephen Owen

***

九州 Jiǔ Zhōu: the Nine Regions or Provinces described in ancient texts that came to be another word for ‘dynastic China’. They became part of the actual administrative system of the Han dynasty

多英俊 duō yīngjùn: ‘numerous talents’ or outstanding people

萬馬齊喑甚可哀 wàn mǎ qí yīn shèn kě āi: a slight reworking of Gong Zizhen’s original line ‘thousands of horses all struck dumb/ is deplorable indeed 萬馬齊喑究可哀’. After 1976, the late-Cultural Revolution period was frequently referred to as one of cowed silence when ‘thousands of horses were all struck dumb’

屈賈阮白 Qū Jiǎ Ruǎn Bó: Qu Yuan, Jia Yi, Ruan Ji and Bo Juyi, talented but disaffected writers who were famously critical of the their times:

- Qu Yuan (屈原, c. 343-278 BCE): regarded as the ‘archpoet’ in the Chinese language. He is also believed to be the first identifiable ‘protest poet’ in the tradition. For more on Qu Yuan and the annual festival that commemorates his suicide, see The Double Fifth and the Archpoet, China Heritage, 30 May 2017)

- Jia Yi (賈誼, BCE): author of ‘The Faults of Qin’ 《過秦論》, a celebrated early analysis of the rise and fall of the tyrannical rule of Qin. Qu Yuan and Jia Yi’s names have been linked — as 屈賈 Qū Jiǎ — since the time of Sima Qian, the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty, who included a joint biography of the two disaffected and tragic writers in his Historical Records. See 司馬遷,《史記卷八十四 · 屈原賈生列傳第二十四》

- Ruan Ji (阮籍, 210-263 CE): a writer famed for his uncompromising attitude and one of the ‘Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove’ 竹林七賢 zhú lín qī xián. As Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444 CE) wrote in New Sayings of the World 世說新語: ‘The seven used to gather beneath a bamboo grove, letting their fancy free in merry revelry. For this reason the world called them the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove’ 七人常集於竹林之下,肆意酣暢,故世謂竹林七賢 (trans. Richard B. Mather). Ruan is known for the eighty-two ‘Poems of My Heart’ 《詠懷詩》Yǒng huái shī which, as Donald Holzman says: ‘describe his anguish and fear and his desire to find constancy and purity in an inconstant and impure world.’

- Bo Juyi (白居易, 772-846 CE): whose ballad ‘The Everlasting Wrong’ is discussed in the notes to the second poem

杜口 dù kǒu: ‘to block mouths’, ‘to stuff a mouth so it remains silent.’ Feeling constrained to keep quiet 噤聲 jìn shēng or to have one’s mouth shut 鉗口 qián kǒu, are like a threnody that reverberates through Xu Zhangrun’s works translated in China Heritage (see The Xu Archive).

The early Qing writer Tang Zhen (唐甄, 1630-1704) used the expression 杜口dù kǒu when commenting on the oppressive atmosphere of his day:

The grandiloquent debaters with piercing views

are silent now, their mouths shut tight.

昔之雄辨如鋒者,今之杜口無言者也。

— 唐甄, 《潛書 · 除黨》

In 1977, not long after I met the playwright Wu Zuguang (吳祖光, 1917-2003) in Beijing, he told me that, apart from the crime of hosting his own literary salon, he had been condemned as an ‘Anti-Party Rightist’ for comments he had made during the Hundred Flowers movement two decades earlier. After lambasting the Communists for their increasingly stifling control over culture and the arts in an article published in a 1957 issue of the professional journal Theatre 《戲劇》 titled ‘On the Theatre and Party Leadership’ 談戲劇工作的領導問題, he asked:

‘Why do people in the arts need your “leadership” anyway? Who among you can tell me the Party Secretary who provided leadership to Qu Yuan? Or, for that matter, Li Bo, Du Fu, Guan Hanqing, Cao Xueqin or Lu Xun? And what about Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Beethoven and Molière?… 對於文藝工作者的‘領導’又有什麼必要呢?誰能告訴我,過去是誰領導屈原的?誰領導李白、杜甫、關漢卿、曹雪芹、魯迅?誰領導莎士比亞、托爾斯泰、貝多芬和莫里哀的?……’

(Among those who denounced these comments the cruelest barbs were launched by Zuguang’s old friend Lao She, a man now regarded as some kind of martyred cultural saint. Lao She had only just denounced the need for ‘so-called creative freedom’ so now, in an article titled ‘Why is Wu Zuguang’s Fury so Dramatic?’ published in People’s Daily — 老舍,《吴祖光为什么怨气冲天》, 1957年8月20日 — he declared that ‘I feel even to have known someone like Wu Zuguang is like a stain on my character’.)

In August 2018, I dedicated my translation of Xu Zhangrun’s essay ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待 to the memory of Wu Zuguang. He was an outspoken man of principle who, even in the darkling years after 4 June 1989, never abandoned his independent critical stance.

Despite China’s relative openness over the past four decades, many other writers, thinkers, public activists and common citizens have been silenced. We will never know what China could have been, or might still become, if this countless multitude was able to speak out, debate and fearlessly participant in that country’s hamstrung public life

枉勞天帝降人才 wǎng láo Tiān Dì jiàng réncái: ‘In vain was the Lord of Heaven’s gift of talents’, a reworking of the last lines of Gong Zizhen’s 1839 poem quoted in full above:

我勸天公重抖擻,

不拘一格降人才。

I urge the Lord of Heaven

to shake us up again

and grant us human talent

not bound to a single kindHere, the modern poet is suggesting that Gong Zizhen’s wish, expressed 180 years ago, seems finally to have been granted by the ‘Lord of Heaven’ and China may be populated by talents of various kinds as a result of a decades-long ‘shake up’ 抖擻 dǒusǒu. He says that to have silenced great writers like Qu Yuan, Jia Yi, Ruan Ji and Bo Juyi because of their disagreeable views would have left China far poorer. Similarly, today, as is demonstrated by the persecution of the outspoken Xu Zhangrun, the country could lose real talents — and not just Xu, but many others possessed of great potential. So the author laments that due to their behaviour the Communists are squandering the long-awaited bounty of ‘human talent not bound to a single kind’

Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance

(March 2019-)

- Chris Buckley, ‘A Chinese Law Professor Criticized Xi. Now He’s Been Suspended’, New York Times, 26 March 2019

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華, ‘J’accuse, Tsinghua University!’, China Heritage, 27 March 2019

- Zha Jianguo 查建國 et al, ‘Heads or Tails — Criticism and Xu Zhangrun’, China Heritage, 29 March 2019

- Anon, ‘Silence + Conformity = Complicity — reflections on university life in China today’, China Heritage, 30 March 2019 (revised 2 April 2019)

- Wang Changjiang 王長江, ‘Tsinghua University Gets a Lecture on Leadership from the Central Party School’, China Heritage, 31 March 2019

- Various hands, ‘Speaking Up for a Man Who Dared to Speak Out’, China Heritage, 1 April, 2019

- Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, ‘My Tsinghua Lament’, China Heritage, 3 April 2019

- ‘An Open Letter to the President of Tsinghua University’, China Heritage, 5 April 2019

- The Editor and Tao Haisu 陶海粟, ‘Poetic Justice — a protest in verse’, China Heritage, 5 April 2019

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-