The Tower of Reading

興趣

This is a companion piece to On the Spur of the Moment, a chapter in The Tower of Reading focussed on an anecdote in New Tales of the World 世說新語. The anecdote is about a visit that the calligrapher Wang Huizhi nearly made to see the recluse Dai Kui on one snowy night in the fourth century. That occasion is immortalised in the expression 雪夜訪戴 xuě yè fǎng Dài, literally, ‘visiting Dai [Kui] on a snowy night’.

What follows can also be read as a stand-along mediation on cultural personality types, literature, language and aesthetics. It is also an investigation into aspects of the individual, the idiosyncratic and the immortal impulse to resist.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a series inspired by the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our interpretive translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年). The short title for this endeavour in China Heritage is simply The Tower of Reading.

Each chapter in Zhong Shuhe’s original series featured a Classical Chinese text of under 100 characters accompanied by a translation into Modern Chinese. To these Zhong appended ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, both modern terms for such works that are akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or incident. Often, Zhong’s comments offer a whimsical reflection on his life.

The Tower of Reading features translations of the classical texts and of Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive essays along with the original Chinese versions of both. To these we add relevant scholarly and interpretive material, as well as art work, that reflects our approach to New Sinology.

For more on the background to this project, see Introducing The Tower of Reading.

***

This two-part chapter is the eighth of eleven selections from New Tales of the World 世說新語, ascribed to Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444 CE). This famous and popular fifth-century selection of anecdotes, stories and witticisms, is known in English translation as A New Account of the Tales of the World.

Previously, we introduced New Tales of the World with a short essay by Richard Mather, the scholar who translated the full text of that work (see ‘If this is what becomes of trees …’). In On the Spur of the Moment, Part One of this chapter, we focussed on a famous anecdote from Liu Yiqing’s New Tales and touched on the Chinese art of the recluse. In his comment on the story of Wang Huizhi deciding on a whim to visit the recluse Dai Kui one snowy night, Zhong Shuhe observed that:

In a time of chaos and disunity, where the Confucian rites and laws have collapsed, scholars finally felt as though they were free to think and behave according to their natural propensities. It was an era in which people felt that they could act according to impulse and speak in a manner that was not circumscribed by the reactions of others, especially the power-holders.

He goes on to say that:

There were a scant few moments in Chinese culture like this — the Wei-Jin period; the Northern-Southern dynasties (220-589); the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-965); and also the Late Ming (1573-1644).

I find some of the individuals from those periods quite fascinating and their words and deeds quite thought-provoking even today.

Zhong Shuhe could well have added two later periods to his list: the New Culture era (1917-1927) and the post-Mao decade (1978-1989). These eras are frequently referred to as the ‘Chinese Enlightenment’ and the ‘New Enlightenment’ respectively. Both were curtailed by civil strife, war and political repression.

The New Culture era flourished during the chaotic early years of the Republic of China which was founded following the collapse of the Qing empire and the end of over two millennia of dynastic politics. Activists in all fields of intellectual and cultural endeavour challenged the past and experimented with the new. Here our focus is on those who, while embracing the possibilities of a modern China, identified traditions and ideas that could contribute to the cultural experimentation.

In the twenty-first century, even though an age-old cycle of authoritarian repression and dogmatic thought would appear to dominate the scene once more, things have changed. Both in- and outside the People’s Republic, The Other China flourishes.

***

Below, following a short note on 興 xīng and 趣 qù, what we call the ‘word constellations’, we revisit a series of lectures that Zhou Zuoren, a prominent translator and essayist (and younger brother of the outspoken literary paragon Lu Xun) at Furen University in Beiping in 1932 in which he outlined what he regarded as being the true origins of China’s new literature. Zhou noted that over the millennia, whenever political disunity unseated Confucian orthodoxy, the arts had flourished. He went on to argue that the culture of 性靈 xìng líng — a deep-seated and unique sense of self — championed by a number of writers during the Ming dynasty foreshadowed the literary revolution in the early twentieth-century and the humanistic aspirations of some segments of Chinese society.

Fifty years after Zhou Zuoren made his case at Furen University, writers, editors and artists revived his argument just as the Chinese arts witnessed a renewed interest in the lost tradition of the 1920s. As an editor in a leading publishing house in south China, Zhong Shuhe played an important role in that journey of self-discovery. I happened to be one of the readers who was caught up in the spirit of the time.

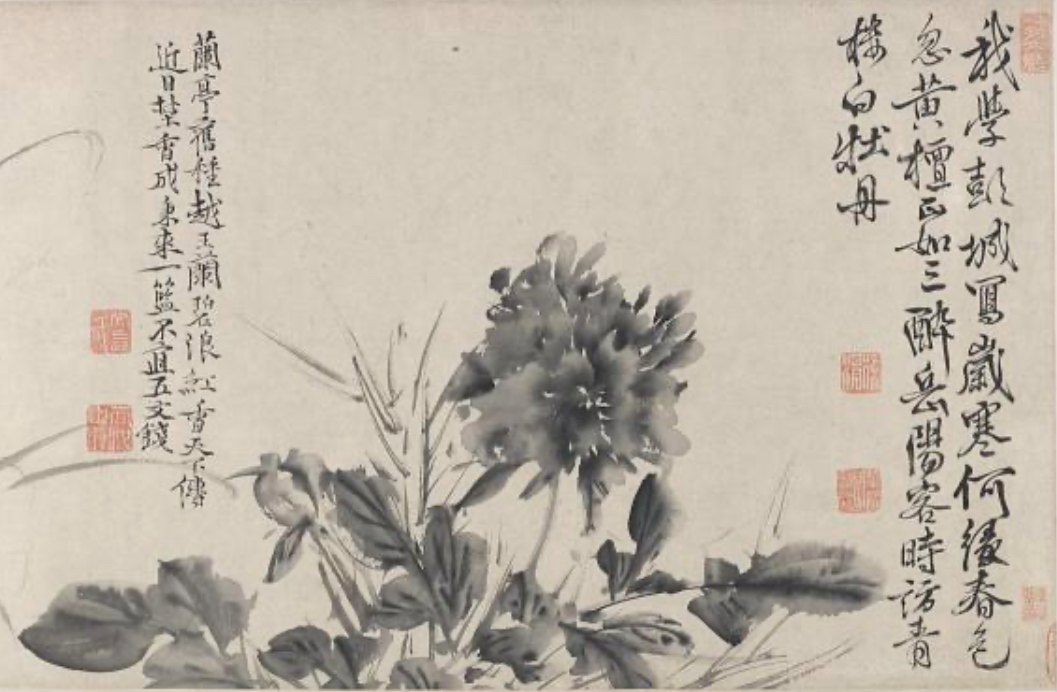

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Huang Yongyu (黃永玉, 1924-2023) the artist, essayist and raconteur who I was introduced to by Xianyi and Gladys Yang. In turn, in 1981, Yongyu recommended that I read Yuan Hongdao, the Late Ming writer mentioned below, and introduced me to Zhong Shuhe.

Yongyu, a celebrated aphorist and humourist, was given to quoting New Tales of the World and making paintings on themes suggested by that work. A favourite anecdote was:

When Huan Wen was young, he and Yin Hao were of equal reputation, and they constantly felt a spirit of mutual rivalry. Huan once asked Yin, ‘How do you compare with me?’ Yin replied, ‘I’ve been keeping company with myself a long time; I’d rather just be me.’

桓公少與殷侯齊名,常有競心。桓問殷:卿何如我。殷云:我與我周旋久,寧作我。

— from ‘Grading Excellence’ 世說新語·品藻, in Richard Mather’s translation, p.277

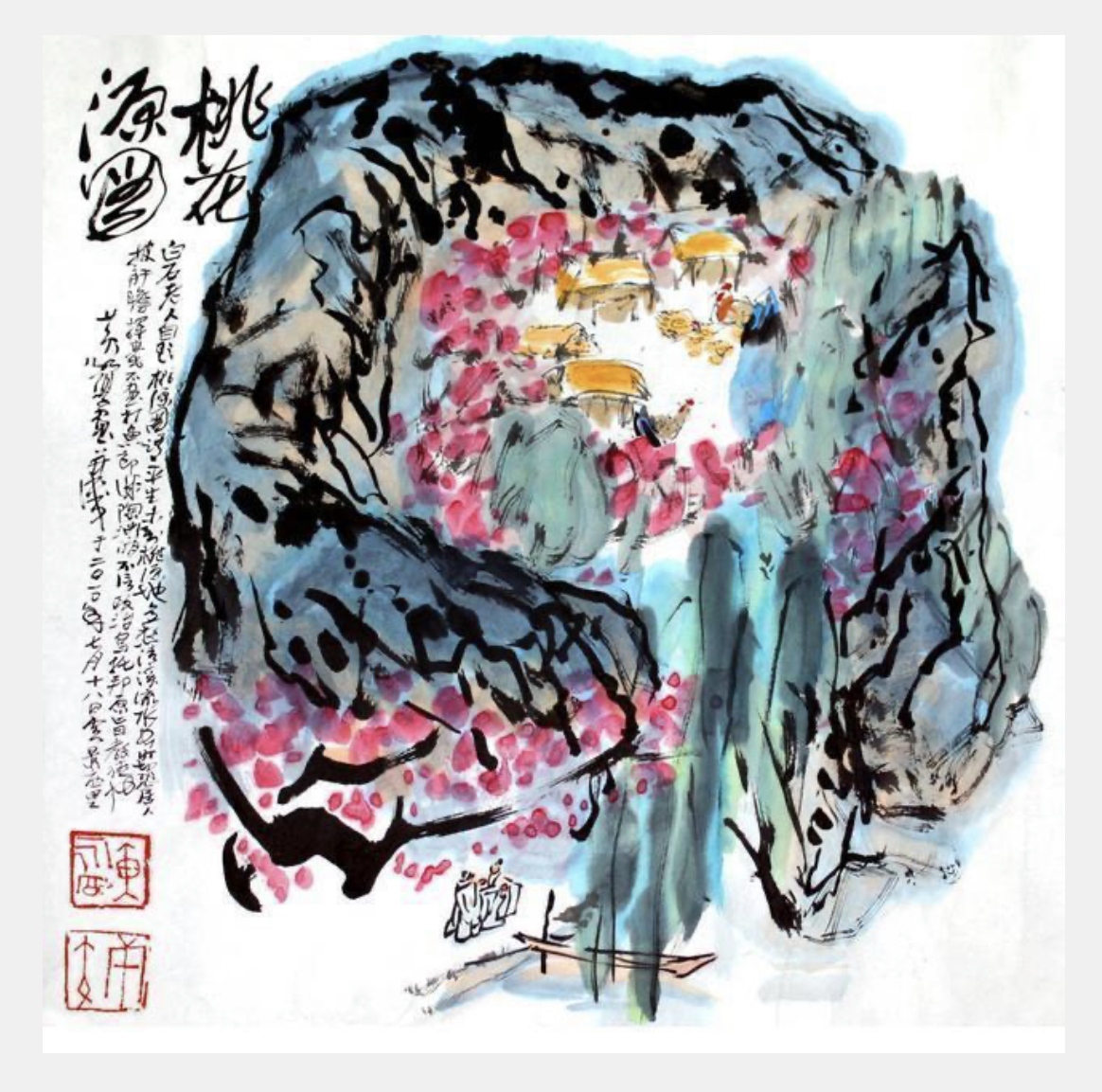

We conclude our discussion with a painting by Huang Yonghou (黃永厚, 1928-2018), Yongyu’s independent-minded younger brother, on the theme of the Peach Blossom Spring, the idyllic vision created by Tao Yuanming (陶淵明, 365-427 CE) during the ebb of the chaotic and creative era that produced Wang Huizhi, the protagonist of ‘Visiting Dai Kui on a Snowy Night’.

(Yonghou’s art often drew inspiration from Liu Yiqing’s New Tales of the World and the idiosyncratic characters, 名士 míngshì, that populate its pages. Friends and critics even remarked that Huang’s personal style and private life were both characterised by what is celebrated as the uncompromising air of a ‘Wei-Jin eccentric’, 魏晉風度 Wēi-Jìn fēngdù.)

***

My thanks again to Reader #1 for looking over the draft of this essay and pointing out typos and various infelicities. As ever, all remaining errors are mine.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 April 2024

***

The Word Constellations 興 xìng and 趣 qù

興 xing: inspiration, happy mood, enthusiasm to do something. One can have shi xing [詩興], or “mood for poetry,” or jiu xing [酒興] or “mood for drinking.” This mood is either deep or shallow. It is an important element of poetry.

趣 qu: interesting, having flavor, the quality of being interesting to look at. A scene or a man possesses or lacks this qu. In particular, qu denotes an artistic pleasure, like drinking tea, or watching clouds. A vulgar person is not supposed to “understand qu.”

— from Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, New York, 1937, p.435, romanisation converted to Hanyu Pinyin

These two entries appear together in ‘A Chinese Critical Vocabulary’, an appendix to The Importance of Living, the best-selling book that Lin Yutang published in 1937. I encountered these terms as a teenager when I read my mother’s copy of Lin’s book. Studying Modern Chinese under Pierre Ryckmans nearly a decade later, I learned that the vernacular expression 興趣 xìngqù, a combination of 興 xìng and 趣 qù which were familiar to me from Lin Yutang, meant ‘interest, fascination with, desire for’ and that it frequently occurred in the phrase 興趣愛好 xìngqù àihào, interests and hobbies.

On the Spur of the Moment, Part One of this chapter in The Tower of Reading, revolves around what, for want of a better term, I think of as the two ‘word constellations’ — 興 xìng and 趣 qù.

A constellation is ‘a group of stars that forms a shape in the sky and has a name’. A word constellation in our sense is a term or word around which a number of expressions connected by meaning form a discernible lexical, poetic and imaginative whole. A morpheme like 興 xìng (read xīng when acting as a verb) will have a range of meanings that have accrued over millennia and which can be modified or extended, often in unexpected ways, by the addition of other equally meaning-laded morphemes. By consulting dictionaries the student can appreciate the spectrum of meanings and uses of a word/ character, but it is by using it — in speech, by listening, reading and through discovery over time — that its capacity is revealed. Some pinpoints of light given off by these word-constellations are readily evident in Modern Chinese, although texts in the classical language — poetry, prose, inscriptions on paintings and works of drama — can reveal their true coruscating scale and significance.

As we noted in Part One, 興 xīng/ xìng means variously to rise, inspire, evoke, stir up, generate delight , interest or excitement. Its ancient use relates to poetic stirrings and the welling up of feeling. In the Analects the Master says: ‘Draw inspiration from the Poems; steady your course with ritual; find your fulfillment in music.’ 子曰:興於詩,立於禮。成於樂。(Simon Leys, The Analects, p.36; 《論語·泰伯》.)

In his explanation of the Six Principles 六義 of poetry enumerated in the ‘Great Preface’ of the classical Book of Songs 詩經·大序, Stephen Owen tells us that:

The category xing 興, “affective image,” has drawn the most attention from both traditional theorists and modern scholars. Xing is an image whose primary function is not signification but, rather, the stirring of a particular affection or mood: xing does not “refer to” that mood; it generates it. Xing is therefore not a rhetorical figure in the proper sense of the term. Furthermore, the privilege of xing over fu 賦 [“exposition”] and bi 比 [“comparison”] in part explains why traditional China did not develop a complex classification system of rhetorical figures, such as we find in the West. Instead there develop classifications of moods, with categories of scene and circumstance appropriate to each. This vocabulary of moods follows from the conception of language as the manifestation of some integral state of mind, just as the Western rhetoric of schemes and tropes follows from a conception of language as sign and referent.

— from Readings in Chinese literary thought, Stephen Owen, ed., Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1992, p.46

As we will see below, the term 興 xìng frequently means impromptu or the inspiration resulting from an encounter with an object, a person or an idea, as in the expression 即物起興 jí wù qǐ xìng. Although the delight of such strong emotion often leaves a sense of loss or sorrow in its wake, famously so in the opening of Wang Bo’s ‘Account of the Pavilion of Prince Teng’ 王勃《滕王閣序》(675 CE), a work about transience and mortality, which includes the famous lines:天高地迥,覺宇宙之無窮;興盡悲來,識盈虛之有數 — ‘The endless expanse of the universe is revealed when contemplating the vault of heaven and the expanse of earth. That in the extremity of happiness lies sorrow is evident when appreciating the workings of fate.’ The expression 興盡悲來 xīng jìn bēi lái, like dozens of other phrases in Wang Bo’s essay, is commonly used in Modern Chinese. Its message is in stark contrast to the impulsive mood of Wang Huizhi summed up in the line 乘興而行,興盡而返: ‘setting off on the strength of an impulse, and turning back when the impulse was spent.’

[Note: The expression 興盡悲來 xīng jìn bēi lái comes from a passage in Wang Bo’s essay which also refers to the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove and to Tao Yuanming. That passage reads in full: 遙襟甫暢,逸興遄飛。爽籟發而清風生,纖歌凝而白雲遏。睢園綠竹,氣凌彭澤之樽;鄴水朱華,光照臨川之筆。四美具,二難並。窮睇眄於中天,極娛游於暇日。天高地迥,覺宇宙之無窮;興盡悲來,識盈虛之有數。望長安於日下,目吳會於雲間。地勢極而南溟深,天柱高而北辰遠。關山難越,誰悲失路之人;萍水相逢,盡是他鄉之客。懷帝閽而不見,奉宣室以何年。]

In Modern Chinese, 敗興 bài xìng refers to something that leeches pleasure from life or an activity. It often appears in the expression 乘興而來,敗興而歸, ‘having set out with high hopes, one returns deflated.’ Although 興 xīng/ xìng also occurs in terms such as 興味 xīngwèi, something that a person takes delight in, and 助興 zhù xīng, to liven things, add to the delight or pleasure of something. Then again, these are but a few examples of what is a veritable constellation of meaning.

As for 趣 qù, the partner of 興 xìng in our discussion, David Pollard notes that in the modern compound 趣味 qùwèi although it embraces ‘the personal idiom, idiosyncratic element, singular character, and particular flavour’ it ‘refers more to qualities in a work that the reader can appreciate, qualities which are often less serious and sententious.’ Indeed, it ‘was also a factor in Zhou’s being associated with the school of Lin Yutang, which might be described as the cult of quirky personality.’ In terms of ‘evocativeness’ in literature and art, as Ye Shi (葉適 1150-1223) of the Southern Song remarks, it denotes ‘something on the other side of words’ 趣味在言語之外. Like 興 xìng, 趣 qù gestures towards things that words only hint at.

***

In contemporary China, 趣 qù is often reduced to a cutesy affect (things can 有趣兒: be amusing) and 興 xīng regularly features in the grand national narratives (as in the ‘renaissance’ 復興 fùxīng of the China Race). The Party-State media is obsessed with rising and declining empires and world powers and when Xi Jinping is much given to using traditional expressions as 興衰存亡 xīng shuāi cún wáng and 興亡更替 xīng shuāi gēng tì as calls on the nation to be ever-vigilant against enemies and ever-ready to protect the Party’s Rivers and Mountains. There are tireless admonitions about the duty to support the regime which often quote the Ming-Qing thinker Gu Yanwu (顧炎武 1613-1682) to the effect that 天下興亡,匹夫有責 tiānxià xīng wáng, pǐfū yǒu zé, even the most lowly has a responsible role to play in the fate of the state. Beijing’s effective abandonment of the unruly ‘One Country, Two Systems’ governance model of Hong Kong after years of popular unrest has, it is now claimed, allowed the former British territory to ‘build on orderly governance so as to achieve revived prosperity’ 由治及興 yóu zhì jí xīng.

***

My initial encounter with the world of the Wei-Jin period as a teenage reader of Lin Yutang was followed some years later by a depressing reality. Studying Classical and Modern Chinese Literature at Maoist universities in the mid 1970s, I learned that apart from a few dismissive footnotes in the works of Lu Xun little else remained. Furthermore, the term 趣味 qùwèi was associated with some of the most negative and retrograde elements of social behavior and popular taste. I learned that decades earlier, Chinese writers and artists had been reprimanded for ‘pandering to the degraded tastes quwei of certain backward elements among the masses’; furthermore, when party critics wanted to condemn a cultural work or notion as being unsuited to the positive and uplifting values of revolutionary culture they often singled it out for vulgarity 低級趣味 dījí qùwèi.

After leaving China in 1977 to work with a Hong Kong publishing house that also boasted one of the colony’s best bookstores, I was able to read widely, including the essays of Lin Yutang and Zhou Zuoren, among others. It was also then that I came across Artistic Taste 藝術的趣味, a collection of essays by Feng Zikai published in 1934. A few years later, I had the good fortune to meet Zhong Shuhe, whose work is the inspiration of The Tower of Reading series, just as Chinese readers were being re-introduced to the anecdotes of the Wei-Jin era, the essayists of the Late-Ming and the independent-minded writers of the Republican era. They all belonged to a world that had been denied and denounced for well over three decades, if not longer. (It was also not too long before, just as their predecessors had done in the 1930s, pro-Party writers were warning of the dangers of what one called ‘a Hippy sensibility’ — the cumulative mentality of a lineage of unique thinkers and creators that could be traced back to Zhuangzi in the fourth century BCE, continuing through the Wei-Jin to resurface in the last century of the Ming dynasty, again in the chaotic early years of the Republic of China and which now threatened to corrupt modern minds once more.)

In my own quest to make sense of that gossamer of cultural connections, I returned to Australia to study under Pierre Ryckmans after having spent a decade in China and Japan. He, and later W.J.F. Jenner, guided my doctoral research into the world of Feng Zikai, Lin Yutang and Zhou Zuoren. Our present discussion of Wang Huizhi, 興 xìng and 趣 qù is an opportunity to return to a topic that has interested me for over half a century and which proved to be both the inspiration for and basis of my academic career.

***

The Tower of Reading is an exercise in New Sinology, a method of engaging with the Chinese world that pays attention to the traditional interplay between literature, history and though 文史哲 wén-shǐ-zhé — the literary, historical and philosophical tradition — and that encourages readers to appreciate, and perhaps even themselves aspire to, the kind of ‘comprehensive knowledge’ that is deeply admired in China. I believe that such an approach allows readers and students to better make sense not only of the then and there, but also of the here and now. Such a quest is not a form of repackaged post-colonial orientalism; the methods and insights of New Sinology are grounded in Chinese ways of seeing, being and imagining.

As I have said elsewhere, New Sinology engages equally with Official China via its bureaucracy, ideology, propaganda and culture, as well as with Other Chinas — those vibrant and often disheveled worlds of alterity, be they in the People’s Republic, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or around the globe. And, as I have repeatedly argued, when things with China ‘went south’ — that is as the systemic inertia of party-state autocracy continued to cast a pall over contemporary Chinese life, as I had no doubt that it would following the events of 1989 — students and scholars would always have recourse to the vast world of literature, history and thought that make a study of China also a study of human greatness, genius and potential. New Sinology is nothing less than a laissez-passer into the Invisible Republic of the Spirit.

We have repeatedly made the case that apart from the broad vistas it opens up on contemporary China, New Sinology also offers balm in the drawn-out days of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. It both offers deeper insights into the Party-Empire of the People’s Republic and The Other Chinas that flourish in tandem with and often in spite of it. In returning to the case made by writers like Zhou Zuoren, Lin Yutang and Feng Zikai nearly a century ago, we pursue an act of sympathetic imagination. In doing so I recall the words of Clive James that I quoted in Cutting a Deal with China, the speech I made when launching China Heritage in December 2016:

In the connection between all the outlets of the creative impulse in mankind, humanism made itself manifest, and to be concerned with understanding and maintaining that intricate linkage necessarily entailed an opposition to any political order that worked to weaken it. …

If the humanism that makes civilization civilized is to be preserved into this new century, it will need advocates. Those advocates will need a memory, and part of that memory will need to be of an age in which they were not yet alive.

***

情 qing: sentiment, passion, love, sympathy, friendly feeling. To be able to understand people or the human heart is “to know renqing or human sentiments [懂人情].” Any man who is inhuman, who is over-austere, or who is an ascetic is said to be bu jin renqing [不近人情] or “to have departed from human nature or human sentiments.” Any philosophy which has departed from human sentiments is a false philosophy, and any political régime which goes against one’s natural human instincts, religious, sexual, or social, is doomed to fall. A piece of writing must have both beauty of language and beauty of sentiment (wen qing bing mao [文情並茂]). A man who is cold or hard-hearted or disloyal is said to be wu qing [無情] or “to have no heart.” He is a worm, or “he has a heart and intestines made of iron and stone” [鐵石心腸].

— Lin Yutang, ‘A Chinese Critical Vocabulary’, The Importance of Living, p.434

***

The Inspired & the Prescribed

In New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices, we used the metaphor of bound feet 纏足 chán zú/裹腳 guǒ jiǎo to discuss the stifling of independent thought and free expression in modern China. The bound foot was a symbol of the bound self, the bones of individuality broken by intellectual convention, social conformism, ideological dogma, and patriarchal power. We referred to true individuals as people who have never allowed their feet to be crushed by convention and who had natural or unbound feet 天足 tiān zú; they were people generally deemed by the rest of society to have grown ‘too big for their boots’.

Reformers, who would loosen the bindings not only for themselves but also for their fellows, were more like women whose bindings have been taken off after they initially had their feet, or spirit, broken by the dogma and convention. While the crushed bones and toes of their ‘liberated feet’ — 放足 fàngzú or 解放腳 jiě fàng jiǎo — might gradually assume a more natural appearance, nonetheless, they were forever condemned to hobble.

We noted that:

… [T]he unfettered, eccentric, and temperamental figures of China’s past and present, [were] people infected with a dangerous spirit of individuality. … For these individualists the bindings of Confucian propriety, the cast-iron mentality of Communism, the swaddling clothes of social acceptability, even the threats of the dictatorial state have no power. Their number may be small, but they have existed throughout Chinese history, often reviled, occasionally revered. In the 193os, a number of writers, including Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang, saw in the individualist tradition within Chinese letters an alternative to the straitjacketed orthodoxy of imperial Confucianism. The individualists are most often appreciated after they are safely dead and gone. They may even attract followers who adorn themselves with the affectations of quirky individuality but wouldn’t dream of tempting the fates by actually rebelling in thought or deed.

— from the section ‘Bindings’ in New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices, Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New York: Times Books, 1992, p.191

The individualists are a chaotic element in a world ordered by orthodoxy; they are the “unbound feet” of society. Their very existence is a threat, their free and unrestrained gait a mote in the eye of both those whose minds have been crippled by convention and those who themselves wish to run but who either cannot or dare not. They are dreaded by all, for they hold up a mirror to their fellows that displays an insipid, weak, and shallow image. As far as many people are concerned, they are better forgotten, dismissed as unrepresentative, or shunted aside.

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the old, rather simplistic, dichotomy between heartfelt writing and prescribed creation described by Zhou Zuoren below finds an echo once more.

— The Editor

***

The Extempore & the Predetermined

David Pollard

即興、賦得

言志派的文學可以換一名稱,叫做即興的文學;

載道派的文學也可以換一名稱,叫做賦得的文學。

— 周作人

Zhou Zuoren’s lectures on the origins of the new literature Xin wenxuede yuanliu 新文學的源流, delivered at Furen University [輔仁大學 in Beiping] in 1932 and prepared for publication the same year, provide the only example of sustained literary analysis by him and so must form the basis for any appraisal of his ideas about literature. The theory central to this analysis is that Chinese literature can be divided into two classes according to the old antithesis between ‘poetry expressing the heart’s wishes’ shi yan zhi [詩言志] and ‘literature as a vehicle for the Way’ wen yi zai dao [文以載道]. Both theses, despite their originally limited field of application, the first to lyrical poetry and the second, less obviously, principally to formal prose, are taken by Zhou in the usual manner to refer to literature in general, so the distinction is between literature simply as an uttering of feeling, free from any direction or control and oblivious of its putative effect, and literature written in the service of a philosophy of life. The one belongs to expressive theory, the other largely to pragmatic theory, but their lines do cross and there is obviously ground for conflict between them. Zhou Zuoren thought them absolute alternatives, and that only one of them, the expressive theory, was valid; literature which sought to be a ‘vehicle for the Way’ (hereafter designated as zai dao) was not literature. …

[Editor’s Note:

‘poetry expressing the heart’s wishes’ 詩言志 shī yán zhì is based on a line in the ‘Great Preface’ of the ancient Book of Songs : 詩者 。 志之所之也 。 在心為志 。 發言為詩 。That is, ‘The poem is that to which what is intcntly on the mind (志) goes. In the mind (心) it is “being intent” (志); coming out in language (言).’ See Owen, Readings in Chinese literary thought, p.40.

‘literature as a vehicle for the Way’文以載道 wén yǐ zài dào is another venerable expression, one forcefully expressed by Han Yu 韓愈, an anti-Buddhist scholar-official of the Tang-dynasty who championed the thoughts of the sages and written style of the past, and Zhou Dunyi 周敦颐, a Neo-Confucian thinker in the Song who saw written expression as a vehicle for the promotion of The Way 道 that had been expounded by the ancients (文所以載道也。輪轅飾而人弗庸,徒飾也,況虛車乎。《通書·文辭》).]

[Zhou] classes different periods as yan zhi or zai dao, according to which outlook prevailed at the time. The ascendancy of zai dao is linked with effective government control of the empire; conversely, the yan zhi thesis comes to the fore when the central government cannot enforce conformity. So in the periodization of Chinese history, from the Spring and Autumn to the Warring States periods, literature was guided by the yan zhi principle, and was therefore good, in Han by the zai dao principle, and therefore poor. In the Wei-Jin-Six Dynasties period it was ‘interesting’, in Tang there was a downturn (the huge volume of poetry produced, encouraged by the state examinations, inevitably threw up many good works, but the situation was different from the creative Six Dynasties period). From the Five Dynasties to early Song, when the ci [詞 lyric-poetry] came into its own, literature was good again, but after Song was firmly established only things tossed off carelessly were written well. In Yuan the shackles were thrown off again, and the qu [曲] resulted. In Ming imitation of the ancients was the accepted dogma (bad), whereas at the turn of the sixteenth—seventeenth centuries the Gong’an 公安 and Jingling 竟陵 schools supported the right line with the slogan ‘if you trust to the wrist and trust to the mouth, all will form melodic numbers’ (xin wan xin kou, jie cheng lü du [信腕信口,皆成律度]). From 1700 to 1900 literature again took the opposite direction, the representative school being the Tongcheng pai [桐城派], advocates of the ‘ancient prose’ style.

It will be seen from the above outline that the yan zhi/ zai dao antithesis is not a very delicate analytical instrument. The Tang dynasty presents an obstacle that cannot so easily be wished away, but an even more important deficiency is the fact, noted by Zhou with regard to the Song dynasty, that many writers had a dual attitude to literature, certain forms being written in the approved fashion and others allowing a free rein, which indicates that the problem lies in personal attitudes, not periods. Furthermore, taking as it does external circumstances as the determining factor, it leaves out of account autonomous developments in literature, such as the exhaustion of genres. The latter is probably the most common explanation for the changes of tack that have occurred over the centuries; it ascribes the high-points in literary history to the creative phases following the ‘discovery’ of genres when authors drew freely and fully on their powers to fill out the form, and the troughs to their awareness in the later stages that wherever they went someone had been there before. It also ignores the more sophisticated theory put forward by Yuan Hongdao [袁宏道 of the late-Ming] of swing and counter-swing, according to which the style dominant in any particular period is explainable by the attempt to correct the excesses of the previous period by taking an opposite line. Zhou did quote, and commend, Yuan’s exposition of this idea in his lectures, but the mechanism of change it postulates is quite different from what Zhou proposes.

[Editor’s Note:

In this context, see Yuan Hongdao’s “A History of the Vase” by Duncan Campbell, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 5, 2 (December, 2003): 77-93.]

The most that can be said for Zhou’s key to literary history is that the average writer might have been deterred from allowing his talents full scope by restrictive conventions, which exerted more influence at some times than at others. Zhou appears to have been aware that he was pressing these concepts into service, for in Lecture Three he puts forward the alternatives of ‘extempore’ (jixing [即興, or spontaneous]) and ‘prescribed’ (fude [賦得, that is, something written to a given theme]). Using these terms he is confident enough to state that all outstanding works of literature have been extempore. The main weakness of ‘prescribed’ literature, he says, quoting Liu Xizai ([劉熙載,] 1813-81), is: ‘Before the opening theme is done, the composition is subservient to me; once the opening theme is there, I am subservient to the composition’ [未做破題,文章由我,既生破題,我由文章]. …

In Lecture Three, after criticizing bagu wen [八股文, rote examination essays produced by aspirants for the traditional civil service] and its counterpart in poetry, shi tie [試帖], he says that though skilful examples of this kind of writing may give the impression of powerful feelings, they are in fact very far from being true literature, as they are brought into being by the prescribed theme. He then proposes that ‘extemporaneous’ could well serve as an alternative to yan zhi 言志, and ‘prescribed’ to zai dao 載道:

The famous works of literature down the ages have all been extemporaneous literature. There were for instance no titles in the Odes [the Confucian Classic of Poetry], and originally there were no chapter headings in Zhuangzi. In both cases there was first the idea, the writing followed immediately on the thought, and only when it was finished was the title abstracted from what had been written. ‘Prescribed literature’ starts with the topic, and the writing proceeds from it.

Zhou had said almost exactly the same thing two years before, in a somewhat lighter vein, for in writing his essay ‘Goldfish’ [金魚] he himself had had recourse to a dictionary for a topic, and so had to chide himself:

I feel all compositions can be divided into two kinds: one has a title, the other does not. Normally the act of writing is preceded by an idea, but there is no definite title … In this kind of composition it would seem easy to produce fine work because you can express yourself comparatively freely, though making up a title afterwards is a nuisance, and is sometimes actually more difficult than writing the piece itself. But there are times too when you cannot gather your stray thoughts together and do not know what to write for the best, in which case it is not without benefit to first decide on a title and then write the piece — only this is getting close to ‘prescribed literature’ and courts the peril of producing an ‘examination-style poem’.

These sentiments are very close to those in a passage he quotes from a book he had read over a period of thirty years, namely Jottings at Jiangzhou, by Wang Kan [王侃,《江州筆談》]:

The ancients only explained the whys and wherefores of a poem after the poem was written: they did not fix on a topic first and then take up the pen to write the poem. …

Though Zhou may have used the term ‘extemporaneous’, and also ‘impromptu’ ou cheng [偶成], which, also being an antonym of fu de [賦得], was synonymous with it, in other places in a casual way, it was only in this kind of context that their use was considered and specific. That is to say, their relevance was to Chinese literary practices, or, more exactly, it was intended to contrast with literary malpractices. As on the question of yan zhi and zai dao, his unqualified approval of ‘extemporaneous’ literature and sweeping condemnation of ‘prescribed’ literature are largely dictated by emotion. Once more we shall call on Zhu Guangqian [朱光潛] for a more balanced view:

In general, literary creation has no more than two starting points. The first is where at the outset there is no intention to write anything; then it happens that the feelings are engaged, an emotional state or train of thought [emerges] which one feels is worth putting in writing, so one takes up the pen and writes it down. The other kind is where one predetermines the topic, and with the intention of writing a literary composition, directs one’s thoughts to that topic; then, when the thoughts have matured, one writes them down. In previous times, when writing old-style poems, people used to add the phrases ‘impromptu’ [ou cheng] or ‘to a given theme’ [fu de] to the titles. The ‘impromptu’ ones arose from a spurring of interest, and were put into verse immediately. The ‘to a given theme’ ones have a set theme and rhyme pattern: the word selected is used as the rhyme for the poem … In principle only impromptu works accord with the ideal of pure literature, but in fact the majority of extant works belong to the prescribed category, as an examination of the works of any great writer would demonstrate. There are of course good compositions in the prescribed group. Not only were good poems written on social occasions and in poetry gatherings, even such things as treatises, memorials, and epitaphs cannot be entirely discounted … ‘Prescribed’ is a kind of training, ‘impromptu’ a kind of harvest. If a writer has not gone through the ‘prescribed’ stage, there might never be ‘impromptu’, or if there is, it could not amount to much.

No more need be said.

— David Pollard, A Chinese Look at Literature: The Literary Values of Chou Tso-jen in Relation to the Tradition,Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973 pp.1-3, 97-99, with romanisation converted to Hanyu Pinyin, Chinese characters added and minor editorial adjustments

[Note: See also Susan Daruvala, Zhou Zuoren and an Alternative Chinese Response to Modernity, Harvard University Press, 2000; and 1946: On Literature and Collaboration, in A New Literary History of Modern China, edited by David Der-wei Wang, Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2017.]

***

偶成

宋·朱熹

少年易老學難成,一寸光陰不可輕。

未覺池塘春草夢,階前梧葉已秋聲。

***

Zhou Zuoren’s View of ‘Taste’ & Tastes

David Pollard

The term quwei [趣味], while … embracing the personal idiom, idiosyncratic element, singular character, and particular flavour, refers more to qualities in a work that the reader can appreciate, qualities which are often less serious and sententious. Quwei loomed large as a literary value both in Zhou Zuoren’s mind and in other people’s conceptions of him. … It was also a factor in Zhou’s being associated with the school of Lin Yutang, which might be described as the cult of quirky personality.

Quwei is such a vague term that we had best look for definitions. The Cihai defines it as a portmanteau word combining xingqu [興趣] ‘interest’ and yiwei [意味], ‘evocativeness’ or ‘implications’. The example cited is by Ye Shi ([葉適] 1150-1223): ‘Strangeness and greatness lie under an unremarkable surface, quwei is on the other side of the words.’ From this we gather that quwei has nothing to do with formal aesthetics, but with qualities in the work that the words only hint at. The example, however, serves only to whet the appetite; we need to follow other tracks.

Of course, as commonly used nowadays, quwei has the sense of ‘interest’, ‘piquancy’ or ‘appeal’, and Zhou often uses it so. Here the only things of significance are what he finds of interest, and the frequency with which he uses the term, not the term itself. It is often linked with the more elusive qualities, like humour, irony and satire, things which do lie below the surface. For instance, Zhou’s judgement on Yu Zhengxie ([俞正燮] 1775-1840) is that ‘his criticism is fair and his style has much comical quwei‘; and he commends the Japanese haibun [排文] (prose pieces related to the haiku) for their ‘pregnant and oddly humorous quwei‘.

More technically, Zhou employs quwei as a rather contrived equivalent of the English word ‘taste’, that is, a set of aesthetic preferences which is subject to variations from age to age: he picks out Keats, for example, as a victim of the adverse ‘taste’ of his times. Zhou recognized ‘taste’ as the basis of all literary appreciation, and by so doing stressed the relativity of critical judgement (thus making himself unpopular with the Left) and the great variety of works that can appeal to different people because of their diverse cultural backgrounds. Though rather unusual in emphasizing these things in his own age, he had of course predecessors in China in accepting the simple fact that individual predilections vary. Cao Zhi ([曹植] A.D. 192-232) was an early one. He wrote:

Everyone has his own preferences. Everyone likes the fragrance of orchids and irises, yet there is also the case of the man who had to leave home because his smell was so offensive yet was much appreciated at the sea-side. All enjoy the sound of the music of the Yellow Emperor and Zhuanxu [顓頊], yet Mozi wrote a diatribe against it. How can there be unanimity?

And Zeng Guofan 曾國藩 was a later one. In his introduction to his Portraits of Great Men 聖者畫像集 he wrote:

In this anthology of poems ancient and modern, from Wei and Jin down to the present dynasty, I have drawn on nineteen authors. Now the scope of poetry is wide, and one’s preferences and proclivities are attuned to what is close to one’s own nature. By way of analogy, if all possible varieties of succulent food were laid out on stands and dishes, I would just eat my fill of those which suited my palate. If I must scour the empire for all its delicacies, judge their flavours and finally present only one dish, that would be a great humbug; if I must compel all the tongues in the empire to like what I want, that would be a great stupidity.

Zhou’s quwei also means ‘taste’ in the sense of discernment. His essay ‘The question of whether old books should be read or not’ [古書可否讀的問題] provides a clear example:

Reading works of literature is like drinking wine: it requires the reader to distinguish alternative flavours. This responsibility lies wholly with oneself, not with the other thing. If someone has not the ability to distinguish the flavours, to the extent of even confusing them, the fault is in himself, that is, he is lacking in quwei.

So far, so straightforward. New subtleties emerge, however, when he eventually comes to discuss the concept directly. This was in 1935, in an essay comparing Li Yu 李渔 and Yuan Mei 袁枚. For convenience I shall continue to translate quwei as ‘taste’. Zhou remarks that Yuan Mei was ‘vulgar, or you could say, tasteless’ 沒趣味, and this gives him his cue:

I have to confess here that I think ‘taste’ is very important; it is both beautiful and good, and tastelessness is a disaster. There are quite a lot of things included in what I call taste, such as refinement 雅, unsophisticatedness 拙, straightforwardness 樸, perspicuity 晴朗, enlightenment 通達, moderation 中庸, discrimination 有別擇, and so on. All things contrary to these qualities are tasteless. There is a phrase ‘low-class taste’ [低級趣味] current which I might as well borrow to elucidate, though it looks as if it has been loaned from Japan, and in my opinion there are semantic objections to it: it is probably more intelligible than ‘tasteless’. Tastelessness is by no means the same as having no taste [無趣味]. Unless he is beyond the reach of human aid, there is normally no one who does not take a particular attitude to life. It may be mild, as if from indifference, or it may be niggling and fastidious, but though tendencies may vary, each and every attitude amounts to a kind of taste. It is like people having different faces: if they preserve their original features, regardless of their beauty or lack of it, they still have a vitality of their own. The worst thing is the spurious kind of tastelessness, or if you prefer it, false taste, bad taste, or low-class taste. To imitate the phrase ‘great wisdom in the guise of foolishness’ [大智若愚], this is ‘great vulgarity in the guise of refinement’.

By contrasting quwei with vulgarity he gives the word the sense of ‘tastefulness’: Yuan Mei’s offence was lack of good taste in expressing a liking for a certain kind of type-face Zhou thought showy. But his reluctance to accept the word ‘low-class’ as a modifier for quwei indicates that it does not correspond with ‘taste’ all along the line: quwei can only be properly described pejoratively as false or lacking. This is because the exercise of any genuinely held personal values in accepting some things and rejecting others is a legitimate assertion of quwei. In other words quwei is an extension of the personality. It is significant that in his amplification of what he himself regards as quwei Zhou picks on qualities consistent with the bent or bias of an individual which would manifest themselves in and through a writer’s work. It seems that the word covers the dual aspects of what the reader brings to his reading and what the writer brings to his writing. This is borne out by Zhou’s description of his attitude towards poetry: ‘I am not concerned with the poetical merits or demerits; actually I just try to make out the author’s character and quwei as revealed in the poetry.’

Quwei is in fact commonly linked with character or personality in Zhou’s critical comments. Of the Japanese monk Kenkō Hōshi (兼好法師] 1282-1350) he says that the greatest value of his work Tsurezure gusa ([徒然草] The Harvest of Leisure) is in its ‘quwei xing‘ [趣味性] (being characterized by quwei): ‘Although there is logical dissertation in the book it is not dry or inhuman, as is usual with dogmatists. It has at its root a kind of warmth and kindness; at every turn he observes society and the world from the point of view of quwei, so even in his sermons there is a rich strain of poetry.’ This is not the only place where Zhou says what is good about Kenkō Hōshi; in an aside during a discussion of Yan Zhitui, he writes: ‘Yan is not narrow, which is where his renqingwei [人情味, humanity, literally, ‘taste of human feelings’] lies. I feel that one also likes Kenkō Hōshi for this.’ These parallel assertions suggest that the degree to which a work has quwei corresponds to the reader’s sense of the author’s personality perceived through it.

Such a bias is understandable when one takes into account Zhou’s agreement with Anatole France that the literary remains of anyone, distinguished or commonplace, are valuable ‘as long as they had something they loved, believed, hoped for, as long as they left part of themselves at the tip of their pen’, and Zhou’s own unsolicited confession that whereas he had previously believed in humanist literature for the sake of the ideas behind it, now (1926) his liking was for the thing itself. The Chinese reader in particular would have been prepared for this bias. Zhang Xuecheng 章學誠 was not unique in feeling, in Nivison’s words, that ‘the content of wen [文] is not the burden of the message communicated by it, but the quality of the writer’s emotional temper or moral insight manifested in it.’

I have kept to the Chinese word quwei because I cannot think of an English word to translate it: ‘taste’ lacks the extra dimension we have been discussing. But there is a German word, coined by Friedrich Schlegel, which seems to represent the same critical approach, though it too inevitably misses some of its connotations. It does however bring us back to quwei‘s common meaning of ‘interest’. It is das Interessante, used by Schlegel as an antonym to ‘objectivity’. M.H. Abrams explains:

This term he uses in an old sense, close to its Latin etymon: it signifies a lack of disinterestedness, and the intervention in a work of the attitudes and proclivities of the author himself. The work of such a poet … is also said to show ‘manner’ or ‘an individual turn of mind, and an individual turn of sensibility’, as opposed to ‘style’, which signifies an impersonal mode of expression according to the uniform laws of beauty.

Both component parts of quwei, qu and wei have lives of their own, and both figure in Zhou Zuoren’s critical vocabulary in other combinations. Proceeding from the simpler to the more complex, we continue with the second element, wei [味], which is immediately intelligible as ‘taste’ in the gustatory sense, or ‘flavour’.

By itself wei has no special interest, but in certain combinations it has. We had best begin with the gloss the Cihai provides for quwei, namely yiwei [意味], ‘evocativeness’. Zhou applied this term in distinguishing between two approaches to trite subjects:

One is the customary ‘the weather today … ha-ha-ha’; the other is to say ‘the weather today is good’ or ‘is cold’, only then to make some further observations about the cold, to the effect that one saw frost in the morning, or that it is depressingly chilly, so appealing to physical principles or human feelings: then one feels there would be a little evocativeness.

If I might make an unpardonable intrusion myself, Zhou is right to say ‘a little’ evocativeness, for it is only a little, so fearful was he of appearing sentimental. Let me provide a better example to bring out the meaning of yiwei, it is in English, and it comes from the pen of Alexander Smith:

’My son Absalom’ is an expression of precisely similar import to ‘my brother Dick’ or ‘my uncle Toby’ … It would be difficult to say that ‘O Absalom, my son, my son’ is not poetry; yet the grammatical and verbal import of the words is exactly the same in both cases. The interjection ‘O’, and the repetition of the words ‘my son’, add nothing whatever to the meaning; but they have the effect of making words which are otherwise but the intimation of a fact, the expression of an emotion of exceeding depth and interest.

Another key term on this side is hui wei [回味], literally ‘returning’ flavour or after-taste. The importance it had in Zhou’s mind is illustrated in an excerpt from a preface he wrote in 1926. Zhou has stated that the most interesting technique for poetry is xing [興], which in modern terminology would be ‘symbol’, and recalled that xing style had been common in China from the earliest times. The example of it he chooses is the Book of Odes poem ‘Tao zhi yao yao‘ [桃之夭夭], the first verse of which, translated by Waley, runs:

Buxom is the peach-tree;

How its flowers blaze!

Our lady going home

Brings good to family and house.

[桃之夭夭,灼灼其華。之子于歸,宜其室家。]

— Book of Songs, no.113, Mao 6

This poem ‘does not necessarily compare the peach to the bride, neither does it lay down that at the time when the peach blossoms, or in some peach planter’s family, there is a daughter getting married; in fact, simply because there is something in common between the peach blossom’s fullness and fairness and marriage, so it is used to start a train of thought. Yet this creating atmosphere has nothing to do with adumbration, but with expressing the central idea, only in another way.'[Note] Zhou goes on: ‘The Chinese literary revolution is under the influence of classicism (not neo-classicism): all works are like a crystal ball, gleaming and transparent to an excessive degree, without a trace of shadowiness. Therefore they seem to lack a kind of lingering fragrance [yu xiang 餘香] and after-taste [hui wei 回味] .’

[Author’s note:

… The notion of hsing [興] seems to me exactly described by J. S. Mill, when he talked of ‘the power of creating scenery, in keeping with some state of human feeling; so fitted to it as to be the embodied symbol of it, and to summon up the state of feeling itself, with a force not to be surpassed by anything but reality’. T.S. Eliot also seems to mean the same thing by his ‘objective correlative’, which is ‘a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.’ (Both quoted by M.H. Abrams in The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition, 1953, p.25.)]

It is clear from the conclusion that the hsing form is only meant to represent the values of ‘lingering fragrance’ and ‘after-taste’: such a connotation had been given long ago by Zhong Rong’s Shi pin [鍾嶸《詩品》], where he defined hsing as ‘the words already finished, but the sense carrying on’ [文已盡而意有餘,興也。]. Now these terms yu xiang and hui wei are particularly Chinese. Indeed, just previous to this passage Zhou admitted that ‘there are some traditions in Chinese art and thought that possess my heart’. In common use there are phrases that describe the lingering effect, such as ‘reverberating round the rafters for three days’ [餘音繞梁,三日不絕], which refers to music, and other critical terms, such as yu qing [餘情] and yu yun [餘韻] — the latter being the lasting effect caused by the means of expression being in perfect harmony with the state of feelings of the author. As to the first, which means a kind of radiation of feeling beyond the bounds of the words, or simply, emotional overtones, Zhou himself thought it had to be present before a piece of (in this case) prose could claim any literary merit. In his ‘Compendium’ introduction he quotes from an early essay of his, ‘Ancestor Worship’ (1919), and comments:

No matter what tender regard a person might have for his own compositions, I still cannot say that the two passages quoted above are well written. They just pig-headedly put forward one’s own opinion. At the most they argue convincingly, but they have no emotional overtones [yu qing]. (p. 5.)

Again, Zhou brings out the importance of the lingering effect, though in this case he gives no name to it, when he discusses some poems of He Yisun [賀貽孫] (early seventeenth-century):

These ten poems are all doggerel [da you shi 打油詩] and by rights should be beneath notice in literary circles; orthodoxy on the one side objects to their lack of refinement and inability to convey the Way, and orthodoxy on the other side detests them for being too humorous and unable to spread revolution. Actually, to my mind, they are most powerful, at least something is left in the mind after reading them, the effect of which is not necessarily to provoke burning tears, but to make one think. To exhaust one’s energies and strain one’s voice in thumping the table, leaping about and hurling abuse, is to thoroughly unburden oneself; but unburdening oneself is satisfying. It is like getting a heat-rash in summer, if you squirm about … your affliction will be eased. The most unhappy time is when you feel oppressed, and the comic reporting of tragic events does indeed make one oppressed, make one unhappy. If the power of literature is in fanning the flames, then I feel this kind of thing must count as very powerful.

Here Zhou is of course discussing a particular kind of lingering effect, but the general point is that it is contrasted with forthright expression, which gives relief, is soon over and done with, and can be forgotten about. He Yisun’s manner, which Zhou describes as ‘oddly humorous’, is more subtle and ultimately has a more powerful effect because ‘it leaves something behind’.

I have said that the various terms connected with ‘taste’ and ‘after-taste’, ‘overtones’ and so on, have long been part of the vocabulary of criticism in China, but they tend to occur in isolated appreciative comments (by far the greater part of Chinese literary criticism is indeed impressionistic — formulating verbal equivalents for aesthetic effects — rather than analytic). The only seminal critic who comes to mind for giving high place to ‘taste’ in his theory is again Zhong Rong. In his Shi pin preface he asserts the primacy of ‘flavour’ (zi wei [滋味]):

Five-word poetry is at the heart of the verbal art: it is of all forms the one with the most flavour.

It is also in Zhong’s book the kind best suited to the full expression of feeling. Conversely, as one would expect, lack of flavour is a mark of inferiority: so in the poetry of the Yongjia period (A.D. 307-13), ‘the reasoning overpowers the words; it is insipid and short of flavour.’

The first half of the combination, qu [趣], is more difficult to understand, as its use in criticism is far removed from the original meaning of ‘to hasten to’ or ‘tendency’ (in everyday use it means ‘entertaining’ or ‘interesting’ — you qu [有趣]). Wang Mengou [王夢鷗, in his 文學概論] explains it as ‘state of “spiritual life”,’ and ‘direction taken by the thoughts’. I would prefer to describe it generally as a kind of inner logic, through that would not account for all the senses in which it is used. A frequently quoted example of its use comes from the biography of Tao Qian [陶潛]: ‘If only you get the qu in the lute itself, why bother about the sound of the strings?’ [但識琴中趣,何勞弦上聲] At least it is clear that qu is not what the senses directly perceive — ‘the sound of the strings’; it would appear on the strength of this example to be the said inner logic or inner harmony. Alternatively it might be viewed (dare one suggest it?) as the counterpart in art to Tao in Lao-Zhuang philosophy. A more stringent test of its denotations is provided by the following passage. The author is Yuan Hongdao (Zhonglang [袁中郎]):

What men find difficult to attain to is qu. Qu is like colour on mountains, taste in water, bloom in flowers, posture in women. Even the most articulate person cannot begin to describe it, only someone who feels it intuitively knows what it is. People nowadays admire the idea of qu, and strive after its semblance. So they indulge in debates about calligraphy and painting, browse among antiques, thinking it ‘rarified’; or they cast their thoughts on Taoist profundities, flee from the mundane, thinking it ‘aloof’. Then on a lower level there are those fellows in Suzhou who burn incense and brew tea. This kind of thing is just the shell and skin of qu — it has nothing to do with the expressions of vitality [we have mentioned].

Qu owes much to nature, little to learning. As a child one has not heard of qu, yet there is nothing a child does which has not qu. Life has no greater pleasures than at this time when the facial expression is never composed, the eyes are always roving, the mouth is ever on the point of muttering something, trying to speak, and the feet dance and will not be still. No doubt this is what Mencius was referring to when he spoke of ‘staying like a new-born babe’, and Laozi too when he asked: ‘Can you be as a babe?’ This is the ultimate attainment of qu and is of the highest order.

The men of the hills and forests, being free and unconstrained, answer only to themselves, so though they do not seek qu, qu comes near to them. The reason why the naive and the outcasts get close to qu is because of their lack of standing: the humbler the station the humbler the demands. Whether in their taking meat and drink or in their rendition of a song, they follow their inclinations, without inhibitions. Since they have given up expecting anything from the world, they pay no attention to the disapproval and mockery of the world. This is another kind of qu.

When one grows heavy in years, receives promotion, achieves higher status, the body becomes like a fetter, the heart like brambles, and the hair-roots and body-joints are constringed by experience and knowledge. One might penetrate ever deeper into the principle of things, but one gets ever more remote from qu.

[世人所難得者唯趣趣如山上之色水中之味花中之光女中之態雖善說者不能下一語唯會心者知之今之人慕趣之名求趣之似於是有辨說書畫涉獵古董以為清寄意玄虗脫跡塵紛以為遠又其下則有如蘓州之燒香煮茶者此等皆趣之皮毛何關神情夫趣淂之自然者深淂之學問者淺當其為童子也不知有趣然無往而非趣也面無端容目無定睛口喃喃而欲語足跳躍而不定人生之至樂真無逾於此時者孟子所謂不失赤子老子所謂能嬰兒葢指此也趣之正等正覺冣上乘也山林之人無拘無縛淂自在度日故雖不求趣而趣近之愚不肖之近趣也以伙品也品愈卑故所求愈下或為酒肉或為聲伎率心而行無所忌憚自以為絕望於世故舉世非笑之不顧也此又一趣也迨夫年漸長官漸高品漸大有身如梏有心如棘毛孔骨節俱為聞見知識所縛入理愈罙然其去趣愈遠矣 … From Yuan’s introduction to a collection by Chen Zhengfu 敘陳正甫會心集.]

***

***

Qu, we gather from the analogy with sensible objects (‘colour on mountains’, etc.), is an intangible quality inherent in, typical of, and unique to a class of things, being particularly evident in the finer specimens. In this sense it is not far from ‘glamour’; perhaps ‘tone’ would suit. In people it is related to behaviour which is natural, apt, unreflecting, unselfconscious, unforced and free; it comes from following the inner promptings of one’s nature, or from being as one is. One might suggest, again tentatively, ‘flair’ as a translation. Both are of a kind that the spectator would find charming or exhilarating.

In the field of aesthetics, Wang Mengou has criticized Yuan Hongdao’s formulation as inferior to Yan Yu’s in Canglang shi hua, ‘Shi bian’ [嚴羽《滄浪詩話·詩辯》], where his examples are ‘the sound in the air’, ‘colour in the appearance’, ‘the moon in the water’, ‘the image in the mirror’. Yuan refers to intrinsic qualities that are apprehended by the senses, while to Yan Yu the qu lies in giving rise to associations, so that (again) ‘the words are finished, but the idea is never exhausted’. Wang contends that ‘colour on mountains’, ‘taste in water’, etc. are only the ‘saltiness of salt’, the ‘sourness of plums’ (i.e. qualities inherent in and indissociable from particular objects) that Sikong Tu belittled. What Sikong Tu and Yan Yu prized was ‘the sense beyond the words’ and ‘the relish beyond the flavour’. They tended, as we have already seen, to denigrate the importance of imagery, and went directly for, in Wang’s words, ‘the aggregate of feelings and perceptions induced by the imagery’. The distinction is an interesting one, but as far as Zhou Zuoren is concerned, we already know that he thought Sikong Tu’s kind of reasoning too abstruse, so there is no point in pursuing it, though with regard to Yuan Zhonglang’s exposition, it is worth noting that the attributes Zhou called quwei would fit the ‘men of hills and forests’ he described.

It may have by now emerged that qu is the element in quwei that provides the lift or exhilaration. Such a tendency is increased when qu is combined with feng [風] ‘wind’, to form fengqu [風趣]. Zhou used this term more than once, but possibly because it would have been familiar to his Chinese readership, he did not explain it. …

… [A]ll these terms which belong to literary appreciation shows how peculiarly Chinese they are. It is not that modern Western alternatives were not available, it is that Zhou preferred not to accept the Western cast of mind as other critics did, but instead to be Chinese.

— from David Pollard, A Chinese Look at Literature, op.cit., pp.72-81. References and footnotes have been removed, the Wade-Giles romanisation used in the original has been converted to Hanyu Pinyin and Chinese characters and texts have been added where relevant

***

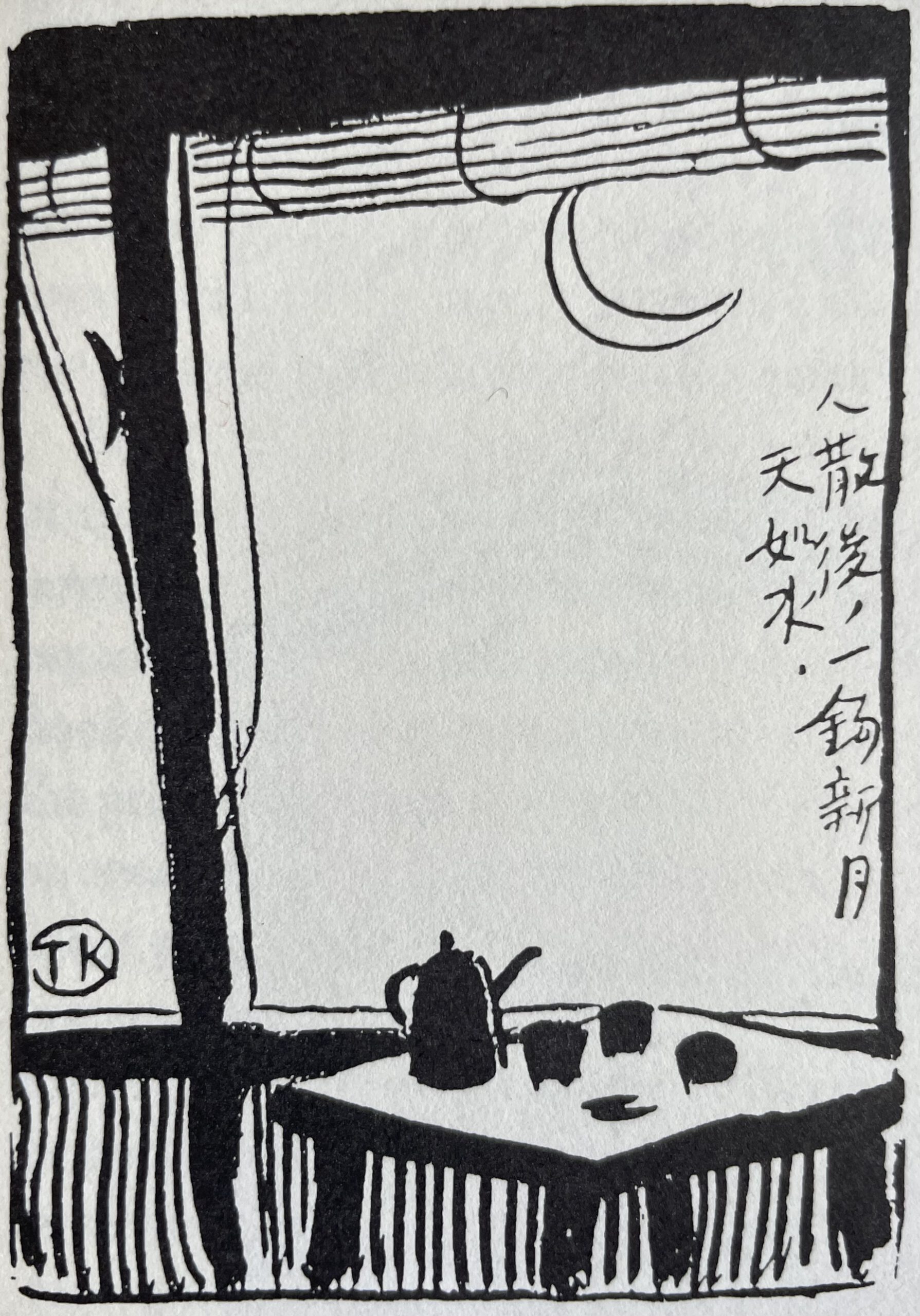

Sense & Sensibility in Feng Zikai

Geremie R. Barmé

Zikai’s first published essay on art, “The Artist’s Life,” which appeared in 1920, had emphasized that any artistic originality required “a unique quwei,” or sensibility, and without this crucial element “an independent spirit, the freedom to create, and all the time in the world will be of no avail.”

The championing of quwei had often been expressed in such extreme and dramatic terms. When discussing the aesthetic training of the modernizing Chinese in “Art and Life,” for example, Liang Qichao had categorically stated, “You may ask, ‘What do people live for?’ And I can answer without hesitation: quwei.” Liang explained that there were three ways in which the individual could realize quwei: first through the re-creation of an aesthetic experience; secondly, from the memory of a feeling or the observation of another’s enjoyment of quwei; and thirdly, by creating an independent world of the spirit. “For the writer that may mean they have to create a Peach Blossom Valley (like Tao Yuanming],” Liang remarked. “For the philosopher it is to postulate a utopia, while for the religious-minded, it is found in heaven or in the Buddhist pure land. In an instant one transcends the world of reality and enters an ideal realm, a place where you are truly free. One way to achieve such a state is through the pursuit of quwei.”

According to this view, the means for inculcating an individual’s sensitivity to quwei was also three-fold: through a training in literature, music, and art. In what appears to be a paraphrase of Liang’s remarks, the young aesthetician Zhu Guangqian, Feng Zikai’s old colleague and friend, wrote in a widely read series of open letters to high-school students published in 1926, “The happiest person in the world is not merely the most active but also the most receptive person. What I mean by being receptive is a person who can find quwei in life.”

Like Zhu, Feng Zikai believed that artistic instruction, a cultivation of the sense of quwei, and the nurturing of “a heart that appreciates beauty” were the keys to any successful education and a happy life.

When the teachers at the Li Da Academy launched Equals in September 1926, they declared in the publication announcement in the first issue that their aim was to provide readers with “articles that, above all, express quwei.” When Zheng Zhenduo visited the Li Da Academy with the editors and writers Ye Shengtao (Shaojun, 1894-1988) and Hu Yuzhi (1896-1986) to see Feng’s manhua, with the aim of selecting some pictures for publication in Literature Weekly, a number of students joined the impromptu gathering. Zheng observed that this private exhibition was a display of the most qu (poetic flavor or intense interest) he had ever encountered.

Xia Mianzun too noted in an essay that was used to preface one of Feng Zikai’s collections that the artist’s mentor Li Shutong (now the monk Hongyi) could find wei, flavor, allure, or interest often a shorthand for the expression quwei — in everything. No matter what he ate, wore, or used, he was able to give himself over to enjoying its particular flavor or essence because he knew how to treat life as a form of art. Only people who could approach life with this attitude of engaged delight or interest could be real artists. It was in this melding of life with culture that art and religion intersected in the everyday world. Xia Mianzun said that he found a similar talent for searching out quwei in Zikai, and that his work, as well as his daily life, were suffused with quwei. Feng eventually chose to call a volume of his collected essays on art The quwei of Art.

However, Feng’s belief in the importance of quwei and the need he felt to instill it in others would increasingly bring him into conflict with his avowedly revolutionary contemporaries. Rou Shi (the pen name of Zhao Pingfu, 1902-31) was a young leftwing writer and artist and a fellow graduate of the Zhejiang First Normal College in Hangzhou. After a fugitive career as an educationalist in Zhejiang, Rou Shi moved to Shanghai in the late 1920s, where he found employment editing various literary journals and working on translation projects under the aegis of Lu Xun. The older writer, a literary celebrity and patron of the left, became his sponsor and even something of a father figure to the aspiring young man. Soon Rou Shi was an active member of the Left League of Writers. He eventually joined the Communist Party, sponsored by his friend Feng Xuefeng (1903-76), a cultural agent working for the party.

In 1930, Rou Shi denounced Feng Zikai in a truculent article in the short-lived journal Shoots. By this time debates in the literary world had moved on from the endless wrangling over technique and genre and were more than ever concerned with the impact of cultural works on the public. Rou Shi’s critique opened with a comment on the artist’s ruminations regarding plum blossoms:

What he is saying in these essays is that young students should abandon their textbooks and become besotted with plum flowers. He seems to hint that if they fail to do so they will lose whatever it is that makes them human. … When I read this stuff I can’t help wondering whether we are being addressed by one of the ancients, or have Lin Pu and Jiang Kui suddenly learned how to write in the vernacular?

Threatened by imperialism and caught in the struggle with the bourgeoisie, a class that was “on a road that led to oblivion,” Rou Shi declared that Chinese students who were willing to abandon their textbooks should not be encouraged to stop and look at the flowers; it was far more important that they learn about the world around them and understand the imperiled society in which they lived.

After visiting members of the oppressed classes, people who are forced to live in boats on the river, they might do well to take the time to observe the white-capped American sailors who roam the streets of Shanghai in pedicabs, twirling their batons. They are the same batons that they use to trounce rickshaw boys whenever they feel they’re going too slow. I think this kind of educational excursion would be far more beneficial and thought-provoking for the young than gazing at plum blossoms. … At least they wouldn’t end up being as woolly-headed as Feng Zikai obviously was when he wrote his essays.

Such an onslaught was typical of the increasingly militant style of critical prose that became common in the small but vocal left-leaning media from the 1920s onwards; it was also characteristic of the ideological animadversion to which Feng Zikai was subjected throughout his life. Although there is no evidence to suggest that he changed the direction of his work as a result of Rou Shi’s vituperation, by 1929 Zikai’s interest in making paintings inspired by poems was waning, as he gradually found new themes in his experiences as a teacher and resident of Shanghai.

This is not to say, however, that Feng Zikai abandoned poetry as a vehicle for and inspiration of his art, for he continued to create paintings with poetic inscriptions throughout his life, although not with quite the energy or unstudied grace of his earlier works. In 1943, he produced a final volume of pictures born from lines of classical poetry. Entitled, appropriately enough, Poetry in Paintings, Feng introduced the book by restating his reasons for favoring a style of art that had motivated so much of his early work:

When reading the poetry of the ancients, I often feel that some of their best lines are equally a description of the lives of modern people, or that they have spoken on my behalf. It is certainly true that poetry expresses deep emotions and, moreover, that human feelings have not changed throughout the ages. Therefore, good poetry is forever new and fresh, no matter how old it may be. This is what people mean when they speak of there being such things as “immortal works.”

Although he gradually found themes for his art in the wider world, if anything, Feng Zikai’s interest in quwei continued to grow. In the 1920s and 1930s, a few nonaligned members of the May Fourth generation repeatedly stressed the development of the individual, or the humanism that they identified as being a central ethos of the intellectual revolution of the early Republic, and they too encapsulated the mood of the culture and the personal style they favored in the words qu or quwei.

Two of the leading proponents of the philosophy of quwei were the writers and editors Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang (1895-1976), men who were to play a pivotal role in helping Feng Zikai find a forum and an audience for his work. For their part, they identified quwei as having been prefigured in the writings of a group of late-Ming scholars; in particular they found evidence for it in the casual essays (or “minor pieces” xiaopin) of the poet and critic Yuan Hongdao (zi Zhonglang, 1568-1610) of Gongan County in present-day Hubei province.

A writer who was critical of the antiquarian and imitative literary style of his day, Hongdao and his two brothers (Zongdao, 1560-1624, and Zhongdao, 1570-1624) were known as the Three Yuans of Gongan, and they used their literary club in Beijing, the Grape Society, as a forum for literary reform.

Hongdao said of the concept that was so central to their artistic sensibility,

This zest [qu] for living is more born in us than cultivated. Children have most of it. They have probably never heard of the word “zest,” but they show it everywhere. They find it hard to look solemn; they wink, they grimace, they mumble to themselves, they jump and skip and hop and romp. That is why childhood is the happiest period of a man’s life, and why Mencius spoke of “recovering the heart of a child” and Laozi referred to it as a model of man’s original nature.

[Note: For a fuller quotation and the original text, see above.]

Among Feng Zikai’s contemporaries, Zhu Guangqian even went so far as to say, “I’ve never been worried by fools, nor by overly clever people, but I’ve always felt it to be pure torture to have to engage in polite conversation with people who are lacking in quwei.” The main proponent of this modern “cult of quwei,” however, was Zhou Zuoren, who praised the liberating power of a newly identified literary and artistic tradition that rejected ideological strictures and narrow orthodoxies, while reaffirming the status and taste of a cultural elite. He regarded the Three Yuan Brothers as the literary forerunners of the May Fourth cultural revolution, although he was soon taken to task for such views by the critic He Kai, who regarded the “literature of quwei” as both harmful to the nation—as it distracted readers from the more pressing issues of the day—and irredeemably self-indulgent.

Zhou Zuoren is an extreme individualist and, as a result, is neither as energetic nor as daring as his brother [Lu Xun] in opposing the powers that be. There is always something weak and reclusive in his attitude; he exudes the style of the dilettante, and has become a loyal advocate for the bourgeoisie.

For Zhou the word quwei meant variously “taste,” a somewhat contrived translation of the English term and, among other things, “discernment.”

One of his observations on this subject is of particular relevance to our appreciation of Feng Zikai’s evolving aesthetic approach in the 1920s:

I believe that the national essence can be divided into two parts. The heredity of quwei is alive and commingled with our very blood. There is no way we can discard it; it finds expression in all of our words and deeds, and there is no need to preserve it, for it simply is. Then there is that dead portion—the morals and habits of the past, which cannot be accommodated with the present. There is no need to preserve this, nor indeed is there any way to preserve it.

By this time, Yu Pingbo was regarded as another purveyor of quwei. Zhu Ziqing, struggling to define his friend’s place on the contemporary scene in an introductory essay for a volume of Hangzhou-inspired essays and poems published by Yu in 1928, wrote:

Recently when talking about Pingbo someone observed that his attitude and style are highly reminiscent of some Ming-dynasty scholar-officials. Of course, I knew they were referring to late-Ming literati like Zhang Dai [1599-?1684] and Wang Siren [1575-1646]. I cannot say for sure what the chief characteristics of those writers should be, but if one were to attempt a definition in our modern colloquial language perhaps you could say they “put quwei above all else.” … I should point out, however, that Pingbo has never consciously imitated them; rather he shares with them a deep-seated sympathy that is a matter of both attitude and personality.

***

***

Lin Yutang and Zhou Zuoren had become involved in a loose coalition of like-minded writers from the late 1920s, who through their casual essays, their causerie, and their lectures and publications, attempted to counter the didactic and propagandist tendencies of the revenant vernacular culture—which they saw as representing both regressive and iconoclastic tendencies in a modern form—by advocating “self-expression” and a “leisurely” style of intimate essays and prose writing. Their search for cultural exemplars was partially a reaction to the attempts by many literary activists (at times including themselves) to identify artistic paragons who would inspire a transformation in the cultural life of the nation. The European powers could all boast their poetic and literary geniuses, it was argued, be they Dante, Goethe, or Shakespeare, and in comparison China seemed to be sorely lacking. Thus, when Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang began to promote the writings of the late-Ming Yuan brothers, they were also advertising their discovery of native genius and a lineage to which they as modern Chinese writers (the progeny, literally or emotionally, of the defunct cultural elite) belonged. It was therefore a search for self-identity that was imbricated with an affirmation of perceived national traditions and self-worth.

In Feng Zikai’s essays the words qu or quwei are often interchangeable with the expressions xingqu or xingwei, In the early 1930s he became a contributor to weekly literary magazines established along the lines of The New Yorker that Lin Yutang founded and edited, shaping them as vehicles for an urbane “literature of leisure” xianshi wenxue [閒適文學], which would appeal to readers through a combination of post-literati culture with a knowing and mellow cosmopolitan modernism. The Lin magazines The Analects and Human Affairs were only two of the many ventures in Shanghai that sought to couple a translated sensibility with a strong local identity, even a reformulated nationalism. As a writer for these journals, Feng was thus soon identified as yet another practitioner of the nonpolitical essay, a voice speaking in the diction of highly personal “self-expression,” yanzhi in Zhou Zuoren’s terminology, or xingling, a term favored by Lin Yutang, which was borrowed from the vocabulary of the Yuan brothers. In 1933, Zikai even went so far as to classify himself publicly as an “amateur” or “dilettante” who found his xingwei in the use of literature or poetry in painting (“literary painting” as he called it, his particular version of contemporary scholar-art), despite the fact that he was by then a successful professional artist. However, regardless of this cultivated braggadocio, he had known for many years that the quwei that he and his fellows so strenuously pursued was expressed in its most unadulterated form not among the public advocates of qu, but in his family, in particular among his children:

Interest or fascination xingwei is something that helps grown-ups face life. In the case of children, however, xingwei is far more than that, for it is the motivating force of their very existence.

— from Geremie R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975), Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, pp.120-127

On Inspiration

from Lu Ji 陸機, ‘A Rhapsody on Literature’ 文賦

We conclude our discussion of spontaneity, taste and tradition with a section of Lu Ji’s rhapsody.

— GRB

***

(i)

As for the interaction of stimulus and response,

and the principle of the flowing and ebbing of inspiration,

You cannot hinder its coming or stop its going.

It vanishes like a shadow,

and it comes like echoes.

When the Heavenly Arrow

is at its fleetest and sharpest, what confusion is there

that cannot be brought to order?

The wind of thought bursts from the heart;

the stream of words rushes through the lips and teeth.

Luxuriance and magnificence

wait the command of the brush and the paper.

Shining and glittering, language fills your eyes;

abundant and overflowing, music drowns your ears.

若夫應感之會,通塞之紀,

來不可遏,去不可止,

藏若景滅,行猶響起。

方天機之駿利,

夫何紛而不理。

思風發於胸臆,

言泉流於唇齒;

紛葳蕤以馺遝,

唯毫素之所擬;

文徽徽以溢目,

音泠泠而盈耳。

(ii)

When, on the other hand, the Six Emotions

become sluggish and foul,

the mood gone but the psyche remaining,

You will be as forlorn as a dead stump,

as empty as the bed of a dry river.

You probe into the hidden depth of your soul;

you rouse your spirit to search for yourself.

But your reason, darkened,

is crouching lower and lower;

your thought must be dragged out by force,

wriggling and struggling.

So it is that when your emotions are exhausted

you produce many faults;

when your ideas run freely

you commit fewer mistakes.

True, the thing lies in me,

but it is not in my power to force it out.

And so, time and again,

I beat my empty breast and groan;

I really do not know the causes

of the flowing and the not flowing.

及其六情底滯,

志往神留,

兀若枯木,

豁若涸流;

攬營魂以探賾,