Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XLIX (supplement)

車軲轆話

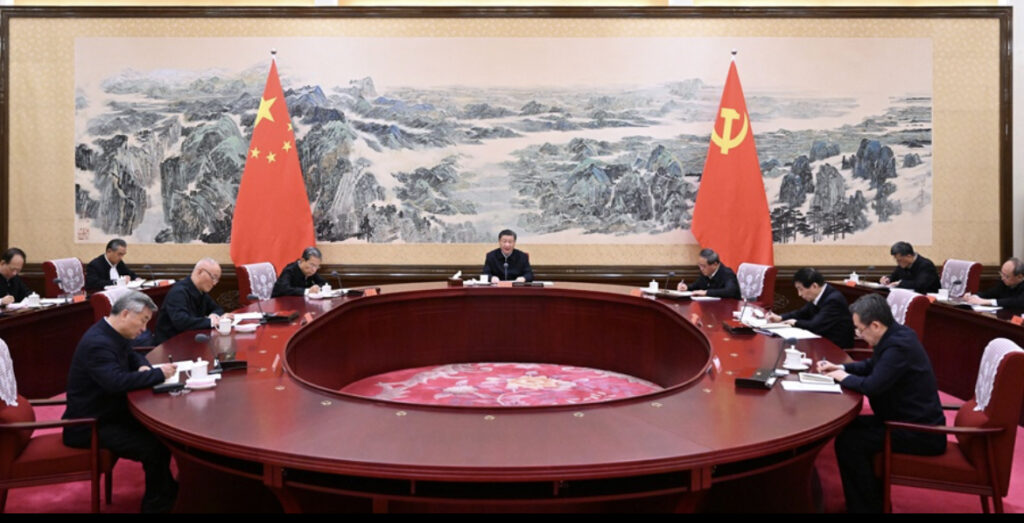

Summing up the essence of the latest ‘Democratic Life in the Party’ meeting of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party [on 21-22 December 2023], the political analyst Deng Yuwen noted that: ‘Xi Jinping called on members of the Politburo to take the lead in understanding, studying, and implementing Xi Jinping Thought.’

This is spot on. It is but the latest example of a familiar refrain: Xi Jinping made an important speech at a meeting focussed on the study of the important speeches of Xi Jinping in which he called on all members of the Communist Party to study Xi Jinping’s important speeches.

習近平在政治局民主生活會上,要求政治局成員帶頭學懂弄通做實習近平思想。沒有曲解官方意思吧。

概括的一點不錯。這已經很多次了——習近平在全黨學習習近平重要講話的會議上發表重要講話要求全黨學習習近平重要講話。

— Hu Ping 胡平, X/Twitter, 22 December 2023

***

Touched by Greatness — Xi Jinping and the Sugarcane of Laibin

Note: Votary fetishism is a widely recognised quirk of Marxist-Leninist regimes. Saccharum officinarum is only the latest object sanctified by Xi Jinping’s laying on of hands.

***

The rubric of this addition to our work on Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is 車咕嚕話 chē gūlu huà — ‘language that goes round in circles’, or repetition ad nauseam. It is published to mark the 130th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth on 26 December 2023.

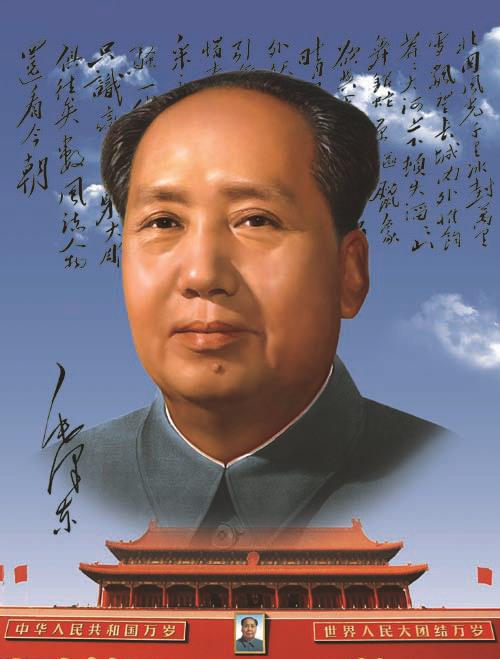

As votary crowds massed at Mao’s birthplace in Shaoshan, Hunan province, to commemorate ‘the miracle of Mao’s birth’ 毛誕 Máo dàn and the long-dead eidolon of the Communist Party and China’s party-state, as they have for over thirty years, it was reported that Xi Jinping, the party-state-army supremo of China would lead his brown-nosing Politburo colleagues to pay their respects to Mao’s embalmed corpse in Tiananmen Square.

[Note: For a video report of Party leaders visiting Mao on 26 December, see here (watch from minute 11:00). This was followed by Xi Jinping delivering yet another ‘important speech’, one in which he congratulated himself by praising Mao.]

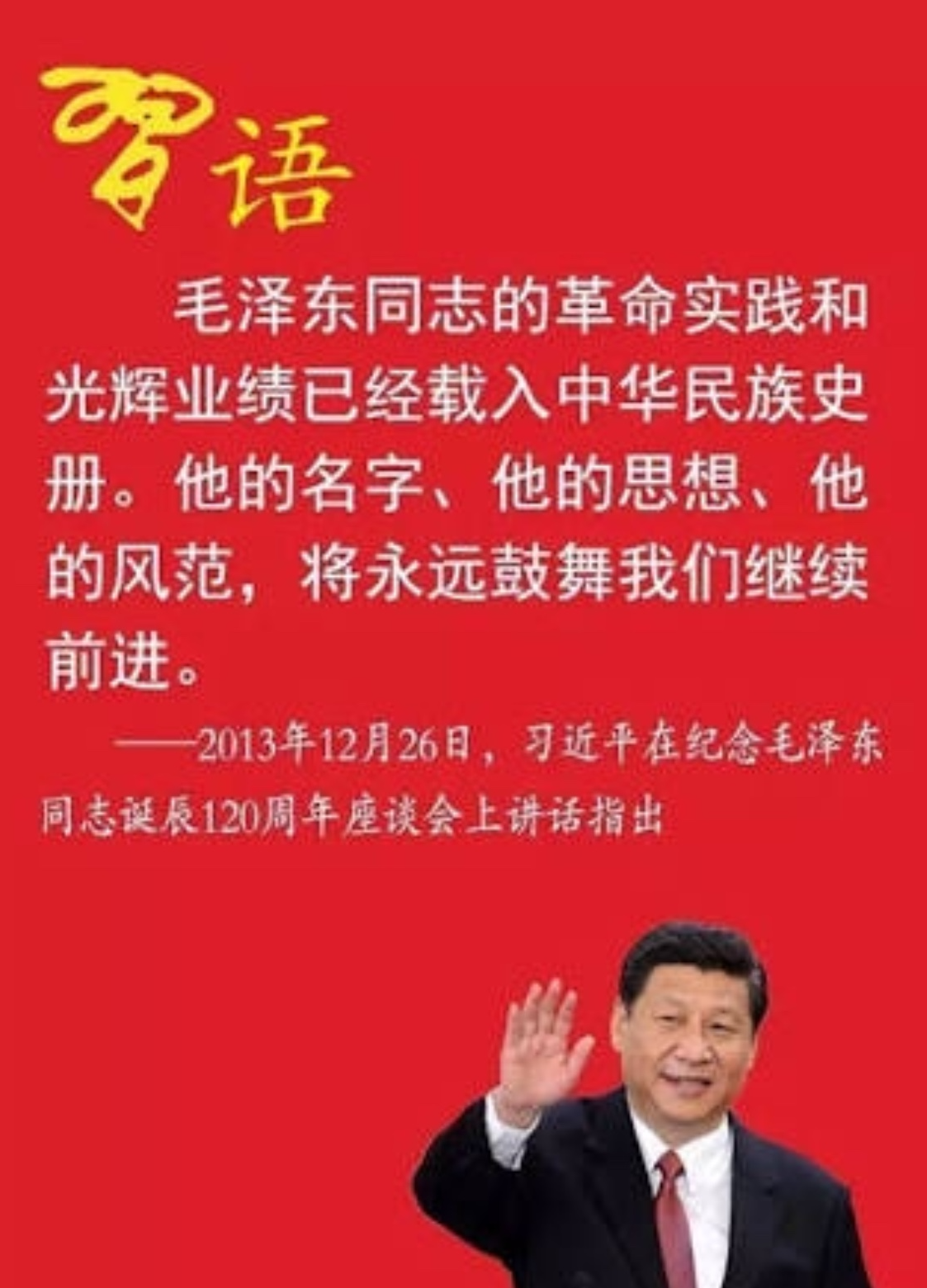

Some days earlier, Qiu Shi 求是, the leading theoretical organ of the Communist Party, had published a paean to the genius of Xi Jinping masquerading as an encomium for Mao. Having equated the two leaders, the authors of the piece concluded that,

‘Although History is created by The People [as Mao himself repeatedly claimed], there is nonetheless a small number of outstanding individuals among The People who have an immense influence on how history actually unfolds.’

歷史是人民創造的,其中包含了少數傑出人物對歷史進程的重大推動作用。

***

We mark this anniversary with some repetitions of our own. As is the case with so much of the material in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we find ourselves reproducing, to the point of ad nauseam, much that has been said previously: 車軲轆話.

First, we recall old warnings about the abiding spectral presence of Mao from the early 1980s. This is followed by an overview of the plans mooted for the building of the Maosoleum in Beijing in 1976-1977 and ‘I’m So Ronree’, a review essay of a best-selling biography of Mao written shortly after Hu Jintao celebrated the 110th anniversary of the Chairman’s birth in 2003. We conclude with another review, this time of a history of the Cultural Revolution published by two noted international authorities on the subject. This is followed by a coda — ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega’ ἐγὼ τὸ ἄλφα καὶ τὸ ὦ — that leads us back to where we began, with Xi Jinping yet again making an important speech about his other important speeches.

***

At a conference held at Harvard University to mark the centenary of Mao’s birth, I presented my findings regarding the popular Mao cult that flourished in the wake of the calamitous events of 1989 and during the Counter-reform years of 1989-1993, which we have observed were but a prelude to the ‘restoration era’ of Xi Jinping. The response of many of the senior academics present — noted political scientists and historians — was generally patronising and dismissive. After all, I was a mere postdoctoral fellow, one at an Australian university at that.

Since Roderick Lemonde MacFarquhar, Stuart Reynolds Schram and Merle Dorothy Rosenblatt Goldman are now all dead, it would be churlish of me to repeat a line that Kingsley Amis jokingly suggested to his friend Robert Conquest for a new edition of his landmark work on the Great Purge of Joseph Stalin:

‘I told you so, you fucking fools.’*

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

24 December 2023

Year XI of Chairman Xi

* For a note on the dissenters from mainstream opinion on that occasion, see Tedium Continued — Mao more than ever, 26 December 2022.

***

Related Material:

- 中共中央黨史和文獻研究院,永遠銘記毛澤東同志的豐功偉績和崇高風範,《求是》2023/24, 2023年12月16日

- 宋丹陽,唱紅歌 拜韶山 抓漢奸 南徵北戰 — 一個毛粉的戰鬥,亞洲自由電台,2023年12月22日

- Geremie R. Barmé, On Understanding Xi Jinping, The New York Times, 5 November 2015

- The Curse of Great Leaders — the Xi Jinping decade and beyond, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 20 July 2022

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 22 October 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, Private Practice, Public Performance: The Cultural Revelations of Dr Li, The China Journal, No. 35 (January 1996): 121-127

- Geremie R. Barmé, Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1995

A loathsome spectre

Prowls the desolation of the land

陰魂不散

***

‘At the center of the center of China lies a corpse that nobody dares remove.’

The line rings as true today in 2023, the 130th anniversary of Mao’s birth, as it did when Behind the Forbidden Door: Travels in Unknown China, Tiziano Terzani’s colourful account of reporting from China, was published in 1985. It echoed a sentiment shared by many Chinese friends in the early 1980s.

Wu Zuguang (吳祖光, 1917-2003), playwright, film-maker and social critic expressed a similar idea when, over lunch in his Beijing home in the summer of 1980 he told me with considerable relish that only that morning at a meeting with pro-Mao Party elders at the Great Hall of the People he had referred to the deceased Great Helmsman as ‘Bandit Mao’ 毛賊 Máo zéi.

In the 1940s, Zuguang was an enthusiastic supporter of Mao and the Communists and, in late 1945, he was the young editor tasked with publishing ‘Snow’, Mao’s most famous poem, in the Chongqing press. The poem was widely seen as reflecting Mao’s imperial ambitions, something that Zuguang agreed with wholeheartedly (see For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone for the text of the poem and a discussion of its significance).

Over lunch that day, and with his wife Xin Fengxia glaring disapprovingly, Zuguang went on to tell me when addressing the gathering at the Great Hall he had gestured towards Tiananmen Gate and declared unequivocally that as long as Mao’s portrait hung over Tiananmen Square and his embalmed corpse occupied its heart China ‘would never really know peace’ 永無寧日.

A few months earlier, in January 1980, the Sichuan writer Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒 published a poem in which he had ominously warned that,

A loathsome spectre

Prowls the desolation of our land.

— adapted from The Unbuilt Wall of Sorrow,

7 November 2017

In Shades of Mao: the Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (New York, 1995), my study of the post-1989 popular Mao revival, I observed that ‘Chairman Mao has entered the stream of Chinese history as man, icon, and myth, and there is little doubt that the Cult of the early 1990s is only the first of the revivals he will experience in what promises to be a long and successful posthumous career.’

Mao is the tutelary deity that animates and inspires Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. In it, gestures towards tradition meld with a worldview of unabashed ambition and political hubris. Paranoid, pusillanimous, reactive and vindictive, the Xi-ist Zeitgeist has seen the re-animation of many traits of the Maoist past and po-faced self-righteous high dudgeon cloaks contemporary China.

From 2009, Party leaders promoted the idea that socialist China enjoyed a reputation for its ‘charisma, empathy and influence’ 感召力、親和力、影響力. They did so even as they demonstrated their approach to international affairs at the Copenhagen Climate Summit in December that year. Today, Xi’s China has oodles of rizz, but it’s all in negative territory and Beijing seems smugly satisfied that, for many, it is neither liked nor likeable.

The above paragraphs are reproduced, with minor changes, from Shades of Mao — Children Spying on Parents, Fragile Hearts in Patriotic Drag and the Fishwife who Trolled Ukraine, 陰魂不散, Appendix XLIX of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, published on 9 September 2023. The present essay, ‘Xi at XI — More Mao than Ever’, is an extension of that appendix.

***

Blurt Out the Truth & Get Smacked in the Kisser

Sag bloß mal einen wahren Satz

Dann kriegst du einen vor den Latz

Wo glotzt des Führers Fratze,

wo Dich an in jedem Dreckbüro

In Kneipen, Straßen und in Zoo

Und lächelt süßlich sauer?

Sein Foto findest du en gros

In jeder Zeitung sowieso

Und darum auch auf jedem Klo

Where is the leader’s face not staring at you —

in every shitty office, in bars,

streets and in the zoo, and smiling that sickly saccharine grin?

You find his photo in bulk in every newspaper regardless,

And that’s why he’s in every loo, as well

***

Note: My thanks to Sebastian Veg for alerting me to In China hinter der Mauer, a track from Wolf Biermann’s 1973 album aah – ja!.

***

An Unquiet Grave

Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé

Imagining Mao’s Mausoleum

Although Mao Zedong had declared himself to be in favour of cremation, within hours of his death on 9 September 1976 a struggle over the fate of his corpse led to a decision being made to preserve his body and place it on permanent public display. Eventually, a formal tomb, the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, was constructed in the southern precinct of Tiananmen Square.

Fig. 7 Mao Zedong’s funeral, Tiananmen Square.

Fig. 8 Aerial view of Tiananmen Gate. A proposed Mao Memorial Hall would have been built between the marble bridges and the gate.

Tiananmen was not the only choice for the construction of a Mao mausoleum. For a time a number of locations for a suitable structure to commemorate the life and achievements of the founder of the People’s Republic of China were under discussion. These included: inside Tiananmen Gate, immediately outside it, on Prospect Hill and even in the Lake Palaces. Considerations to place the memorial in the Lake Palaces 中南海, Mao’s official residence from the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic, would have seen his corpse located in a dedicated hall built on the Ocean Terrace 瀛台, the island in the South Lake 南海, closest to the Chang’an Boulevard entrance to the party-state enclosure. Those in favour of this location also argued that it was the ‘heart’ of the People’s Republic and that it would be easy to protect as the island was isolated and effectively cut off from land by a natural moat. The opposition pointed out that it would be far too close to the working centre of the nation’s political and administrative life, not to mention the residences of key party leaders and their families. Moreover, the Ocean Terrace had been the main location of the Guangxu Emperor’s ‘house arrest’ during the last decade of his life, following the abortive 100 Days Reforms of 1898 and the coup by military leaders who brought the Empress Dowager, Cixi, back into effective control of the empire. It was deemed highly inauspicious for this site to become the eternal resting place of China’s beloved revolutionary leader and founder of the People’s Republic. The proposal favouring the Lake Palaces was abandoned on 14 September, less than a week after Mao’s demise.

After surveys of various other sites by the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall Design Team, including Tiananmen, Duan Men 端們, the Labouring People’s Cultural Palace 太廟, Prospect Hill 景山, Taoran Ting Park 陶然亭公園, the Fragrant Hills 香山, etc, plans were considered for five potential locations. These were:

1. Tiananmen Gate. This proposal was developed in emulation of the Lenin (and for a time the Stalin) tomb in Moscow’s Red Square. The plan would have seen a large building attached to the front of Tiananmen Gate in the location where an altar had been set up for Mao’s funeral on 18 September 1976. The main argument against this proposal was that the area between the Golden Water River 金水河 moat immediately in front of Tiananmen and the gate was relatively small, leaving little room for a structure of suitable magnificence and solemnity. Moreover, the gate itself, which was the ritual centre of state power, would have loomed over the tomb, thereby influencing the visual and symbolic impact of both the tomb and the gate. Lastly, it was noted that such a structure, and access to it, would have created serious transportation problems on Chang’an Boulevard.

Fig. 9 Plans for the Meridian Gate with a commemorative hall built on the site of the demolished Duan Men.2. Duan Men 端們, or the Gate of Rectitude. This is the gate situated between Tiananmen Gate and Wu Men 午門, Meridian Gate, the formal entrance to the Palace Museum. If this proposal had been accepted, Duan Men would have been razed, thereby destroying an integral part of the design of the Forbidden City. Since the area was ‘outside Wu Men’ 午門外, a place used for carrying out the corporal punishment of officials and some executions in dynastic times, it was argued that the place would have been highly inappropriate for the commemoration and mourning of the dead chairman.

Fig. 10 The commemorative hall and cenotaph planned for Prospect Hill to the north of the Forbidden City/ Palace Museum, with a walkway connecting Shenwu Men to Prospect Hill.3. Jing Shan, or Prospect Hill Park 景山公園, immediately to the north of the Forbidden City. It was suggested that a commemorative obelisk facing south be constructed on the summit of Jing Shan, which overlooks the former palace. Visitors would enter the mausoleum precinct via a large tunnel dug through the hill which would contain a lavish crypt for the display of Mao’s preserved corpse. Deliberations touched on the fact that Jing Shan was the site of the 1644 suicide of the Chongzhen Emperor, the last ruler of the Ming dynasty. Moreover, the site was north of the Forbidden City, the heart of feudal China. It was also argued that as the space between the palace and Jing Shan was relatively small, a platform would have to be built between the Shenwu Men 神武門 northern gate of the Forbidden City and the hill, something that would have resulted in a series of architectural and transportation problems.

Fig. 11 The proposed Chairman Mao Mausoleum at the Fragrant Hills.4. At Xiang Shan, Fragrant Hills Park 香山公園 to the northwest of Beijing. The scenery and position of this location was regarded as being suitable for a formal mausoleum (陵 líng, a term used in dynastic times for the burial place of an emperor) similar in design and grandeur to that of the Zhongshan Mausoleum 中山陵 of the ‘father of the nation’ Sun Yat-sen outside Nanjing, the former Nationalist capital.[1] The tomb would look out over Beijing to the south-east. Although a popular choice with the leadership, the major drawback of this proposal was that it would locate Mao’s body too far from the city, making it inconvenient for party-state leaders and the countless mourners who were expected to visit.

5. Tiananmen Square. This site would place the mausoleum to the south of the Monument to the People’s Heroes in the centre of the square. It would create an impressive and solemn site, however, it would do so at the expense of the design of the square itself.

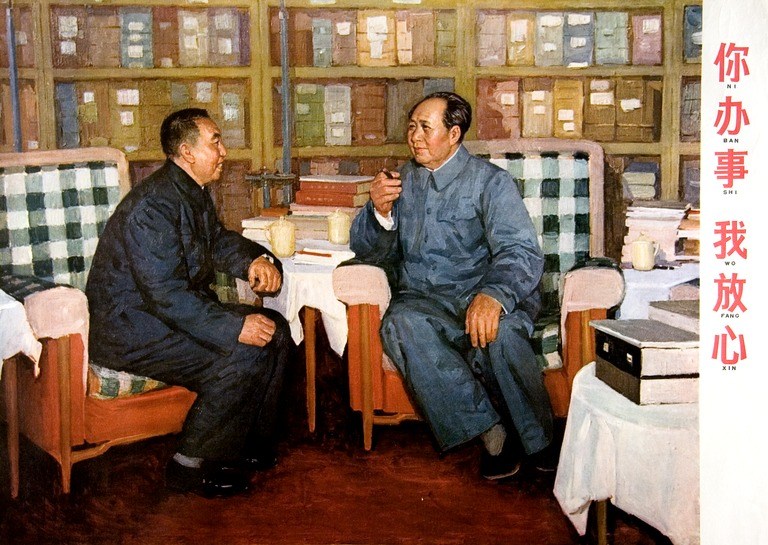

One of the key factors in deciding on the fifth location, south Tiananmen Square, and against the formal tomb in the Fragrant Hills was the opinion of the new Party Chairman, Hua Guofeng. Overriding the expert opinion of architects and advisers, Hua declared that, “Chairman Mao will live on in the hearts of the people. When they gather in mass meetings he will still be in their midst. We don’t want a tomb up in the hills, or just a gravestone. Chairman Mao has to be in a building. He has to have a commemorative hall.” This declaration put paid to the discussions leaving Tiananmen Square as the only viable option.

Fig. 12 China Gate, demolished in 1957 during the expansion of Tiananmen Square, now site of the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall.

In the event, the Mao Memorial Hall was built on the north-south axis of Beijing between Zhengyang Gate and the Monument to the People’s Heroes in the centre of Tiananmen Square. It is positioned on the former site of China Gate 中華門, the Republican and early People’s Republic name of what was originally the Great Ming Gate 大明門, latterly the Great Qing Gate 大清門, which had been demolished during the late 1950s expansion of Tiananmen Square.[2]

However, this decision created a new problem. During future mass meetings, demonstrations and parades, ‘the people’ would invariably stand facing Tiananmen Gate, with their backs to the dead chairman. Hua Guofeng now declared that such a sign of disrespect “would make me feel very uncomfortable”. A member of the design team, Zhao Pengfei (the chief of the Beijing Construction Bureau at the time and a political appointee to the group) came up with a solution by suggesting that the gardens surrounding the commemorative hall should be reduced in size so that during mass rallies people would be able to gather all around the building, bringing to realisation Chairman Hua’s hope that Mao would live forever among the masses.

Once this problem had been solved there were intense discussions over designs for the final building. Architects from throughout the country were invited to make proposals and present them in Beijing. All together, 107 proposals were received. It was hoped that the final structure would outshine the tombs of other famous political leaders throughout the world, besting Lenin’s Tomb, the Lincoln Memorial and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, both in Washington, Georgi Dimitrov’s Tomb in Bulgaria (torn down in 1999), as well as the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum in Hanoi. The most outlandish of the many extraordinary designs was one that featured a 100-metre high red orb symbolising the sun rising in the east. The design that was finally decided on, one for a relatively squat square building, was inspired by a proposal made by Yang Tingbao, the then deputy provincial governor of Jiangsu, a man who had trained as an architect at the University of Pennsylvania.

Fig. 13 A design for the Mao Memorial Hall in Tiananmen Square featuring a ‘red sun’.

A ceremony for the laying of the foundations for the Chairman Mao Commemorative Hall 毛主席紀念堂 was held in November 1976, some two months after Mao’s demise. The building was completed in May of the following year and officially opened on the anniversary of the leader’s death on 9 September 1977. The original sculptures at the gates outside the building were altered in 1980 to remove any reference to the Cultural Revolution. Although Mao’s corpse remains in glorious isolation within the commemorative tomb, the dead chairman was subsequently joined by other Party leaders. From 1983, commemorative halls within the structure also celebrated the lives of Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De. These were joined by displays for Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun in 1999.

***

Notes:

- For more on the funeral of Sun Yat-sen in Beijing in 1925 and his eventual entombment in the Purple Mountains outside Nanjing in 1929, both events which were echoed in the mourning for and burial of Mao, see Henrietta Harrison, The Making of the Republican Citizen, Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp.133-44 and pp.207-35.

- For more on the Mao Memorial Hall, see Rudolf G. Wagner, ‘Reading the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Peking: The Tribulations of the Implied Pilgrim’, in Susan Naquin and Chun-fang Yü, eds, Pilgirms and Sacred Sites in China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992, pp.378-423; and, Frederic Wakeman, Jr., ‘Mao’s Remains’, in James L. Watson and Evelyn S. Rawski, eds, Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988, pp.254-88.

- The members of the Commemorative Hall design team were Xu Yinpei, Yuan Jingshen, Shen Bo, Ma Guoxiang, Geng Changfu, Fang Boyi, Wu Guanzhang and Zhao Pengfei. The worked under the immediate direction of Gu Mu, the head of the CCP Central Committee Office of the Leadership Group in Charge of Preserving Chairman Mao’s Body, although the actual work involved in building the Commemorative Hall has directed by Li Ruihuan.

***

References:

- Mao zhuxi Jinian Tang, Beijing: Renmin Chubanshe, 1979.

- Mao zhuxi Jinian Tang jianzhu tuji, Beijing: Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe, 1979.

- Zhu Wenyi, ‘Tiananmen Guangchang duandai shi’, Sanlian Shenghuo Zhoukan, 2006: 3.

- Liao Gaolong, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo biannian shi, Kaifeng: Henan Renmin Chubanshe, 2000.

- Oral history interviews with members of the original design team: Ma Guoxiang; Yuan Jingshen and Shen Bo.

- Illustrations from: Mao zhuxi Jinian Tang fang’an: caotu in the Archives of the Research Institute of Chinese Architecture (Zhongguo Jianzhu Kexue Yanjiu Yuan dang’an), 1977.

***

Source:

- Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé, A Beijing That Isn’t (Part I), China Heritage Quarterly, No.14 (June 2008)

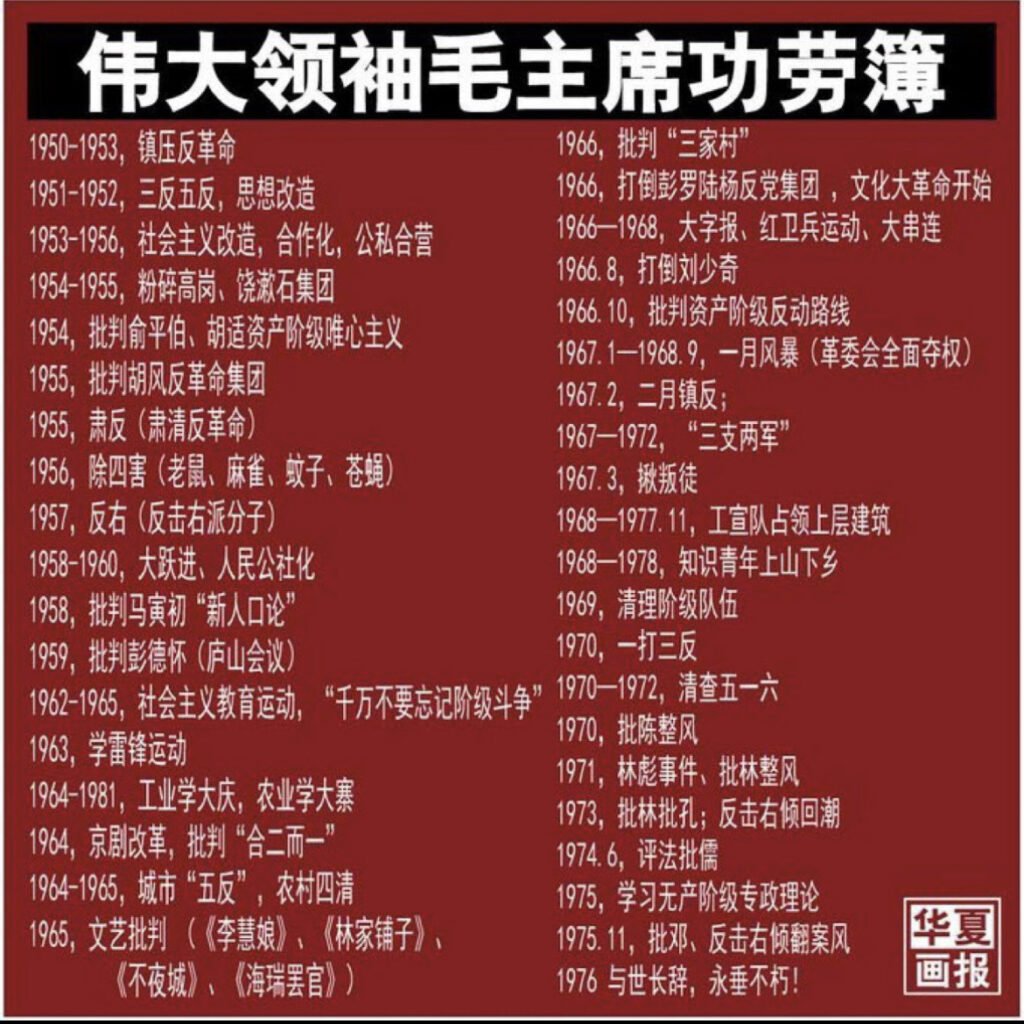

[Note: Absent from this list is the Land Reform Movement of 1948-1950, which involved the mass extermination of ‘class enemies’.]

***

I’m So Ronree

Geremie R. Barmé

He’s Back

With the accession of Hu Jintao to the dual roles of State President and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party’s Politburo in 2002, many presumed that the relatively lax ideological rule of the Jiang Zemin years would continue. Ever-optimistic observers even thought that here, finally, China had a Soviet-style reformist of its own (recall putative Sino-Gorbachevs past, Qiao Shi, for example).

It was probably the 2003 commemoration of the 110th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth, and the speech that Hu Jintao made at the Great Hall of the People in December that year, that put paid to such a notion. Ten years earlier, in 1993, the party had also commemorated Mao, using the centenary to extol the virtues of Deng Xiaoping theory and the direction that the country had taken since the Cultural Revolution. In part, the authorities were also attempting to redirect the popular Mao cult that flourished from the late 1980s, especially after 1989 (a cult which had been evident in nascent form in the 1989 mass protests), an unruly outcrop of mass sentiment chronicled in my study of the ‘posthumous career’ of the Great Leader, Shades of Mao (M. E. Sharpe, 1996).[1]

In a speech delivered on the occasion of the centenary celebrations of Mao’s birth in December 1993, Jiang Zemin had at least made mention of Mao’s errors.[2] For Hu Jintao, on the other hand, the banner of Mao Thought had “always to be held high, at all times and in all circumstances”,[3] and he had nothing but praise for the man who, with his death in September 1976, had bequeathed his country a legacy of arrant politics, economic ruination and profound social anomie.

Hu Jintao has pursued a politics that was evident in his pro-Mao speech of 2003, ushering in a period of increased ideological policing. It is therefore perhaps a good time for there to be renewed work and thought devoted to Mao Zedong and his abiding—I would argue inescapable—patrimony, whether it be in Chinese, or some other international language. Chang Jung and John Halliday’s Mao: the Unknown Story (or The Untold Story, as the North American edition is subtitled) promises, among other things, startling revelations about one man’s monomania, diabolical ego and tireless cruelty. It is a work that provides the reader with a Mao in verso, a dark negative of the CCP’s account. The hyper marketing strategy of its publishers has allowed the book to enjoy a near dream run in the mass media of the Anglophone world. But is The Unknown Story a serious contribution to our knowledge and understanding of a crucially important figure of the 20th century and the history of a country with which his personal story is so profoundly commingled?

Bandit Mao

It was, I recall, in 1980 that I first heard one of my mainland friends use the expression “Bandit Mao”, or Mao zei 毛賊 to describe the dead chairman. He was a veteran writer who had suffered terrible persecution from 1957, and whose wife had been brutally beaten and disabled during the opening months of the Cultural Revolution. We had met shortly after the arrest of the ‘Gang of Four’ at a gathering of literary bon-vivants who had been kept apart by two decades of political persecution. From then on this particular friend—a man now lauded in the Chinese media as a great talent abused during the years of ‘leftist’ supremacy—would often refer to Mao as Mao zei, even, according to both him and other friends, at meetings where pro-Maoist party elders were present. He was also an early and strident proponent in favour of removing Mao’s corpse from his mausoleum, and taking down the portrait that to this day looms over Tiananmen Square.

He was only one of many men and women of conscience, people who had endured the brutalities of the Mao years, who would speak out in various forms against the Chairman and his baneful legacy. There was Wang Keping of the Stars avant-garde art collective, who produced the memorable sculpture of Mao as Buddha in 1978; Bai Hua who published the scenario ‘Unrequited Love’ in 1979; and then, in January 1980, the Sichuan writer Sun Jingxuan who wrote a powerful poem on the lingering leader. In it he ominously warned his readers that, “A loathsome spectre/ Prowls the desolation of your land …”

Despite Deng Xiaoping’s canny move to put Mao in his place, and Party Central’s decision on post-1949 history that provided a final official ruling on the leader’s historical role (and mistakes)—a ruling that Hu Jintao used to his own ends in his 2003 commemorative hagiography—throughout the 1980s Chinese writers and thinkers continued, as best they could, to excoriate and interrogate the burden of Mao. Among my favorites is Li Jie, who used his particular adaptation of psycho-analytic theory and cultural studies to pierce the “fog that Mao shrouded himself in, both intentionally and unintentionally”.[4] This Shanghai author’s analysis of Mao paralleled the Russian philosopher Alexander Zinoviev’s cogitations on Stalin and Stalinism, in which he considers the powerful and complex psycho-political intermeshing of the Russians with their Soviet ruler. As Li says of China’s own leader, “…Mao utilized the weakness of the Chinese to further his own Mao-style revolution …”[5]

I mention here in summary some early attempts by mainland Chinese cultural figures to deal with Mao, despite the pressures of intermittent and egregious official censorship, because if there is one overarching flaw in the Chang-Halliday tome, it is that the authors give scarcely a hint of the complex binding relationship between Mao, his colleagues and those who participated in, created, benefited and suffered from the Chinese revolution, especially following the founding of the People’s Republic of China.[6]

Another reason that 1980s and 90s Chinese-language works on Mao, many of them colorful and fanciful, seem relevant to a review of this book is that in many ways Mao: the Unknown Story, with its histrionic tone and its unwavering certainty, is reminiscent not of, say, the more balanced prose of other recent popular dictator biographies like Ian Kershaw’s work on Hitler, but rather of the bitter glee of so much post-Cultural Revolution mainland Chinese historiography and pop sensationalism. While anyone familiar with the lived realities of the Mao years can sympathize with the authors’ outrage over the atrocities of the time, one must ask whether a vengeful spirit serves either author or reader well, in the creation of a mass market work that would claim authority and dominance in the study of Mao Zedong and his history?

Troubles with the Telling

Having spent some long years working with colleagues in Boston to make a film, and create a website, related to the history of the Cultural Revolution era,[7] and having encountered many knotty issues in the process, I began reading with some anticipation the relevant sections of Chang-Halliday’s Mao, entitled ‘Unsweet Revenge’ (pp. 523-654) which the editors of The China Journal have asked me to concentrate on here. Given the authors’ avowed in-depth research into the machinations of the party elite, and Mao in particular, I was looking forward to at least some new information or consideration of the questions related to the origins and unfolding of the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s motivations, and the history of that period.

My problems and doubts began on the first page of ‘Unsweet Revenge’, and they just kept increasing.

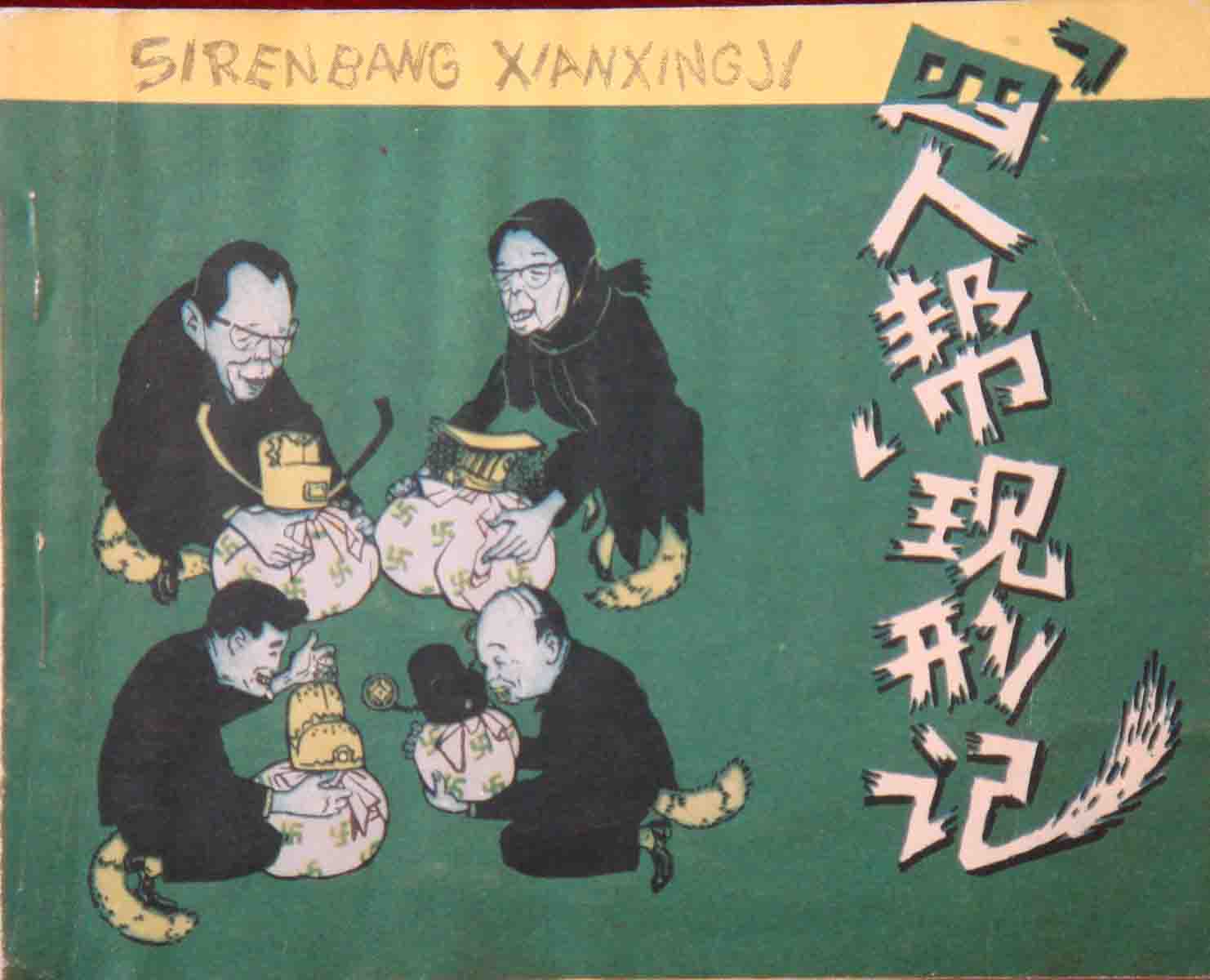

- Jiang Qing is immediately dubbed “police chief for stamping out culture nationwide” (p. 523). Further on the authors tell us that: “In the annihilation of culture, Mme Mao played a key role as her husband’s police chief in this area. And she made sure that there was no resurrection of culture the rest of Mao’s life …” (p.542). This reduces to a parody the long-term and important debates about reform versus revolution, and mass as opposed to bourgeois values, in the Chinese arts that can be traced back to the May Fourth era (1917-27) and which found a clear, if shrill, re-articulation in Jiang Qing’s speech at the PLA arts forum of 1966 (which Chang-Halliday call a “kill culture manifesto”). But then, some sixty pages later, the authors contradict themselves and speak of the partial revival of culture years before Mao’s death (p. 586). One would have thought that given the energy devoted to trouncing Jiang Qing in this book (indeed, a whole chapter is devoted to her role in the Cultural Revolution, see pp. 622-33), it is curious that the authors overlook her role in the denunciation of the film ‘A Life of Wu Xun’, a key moment in the cultural ructions of the 1950s. More generally, their lambasting of cultural debates (no matter how convoluted or driven by power they were) make it hard, no, well nigh impossible, for the interested reader to discern any sense or logic to the Cultural Revolution, or its origins outside of Mao’s supposedly twisted pathology, and Jiang Qing’s mania;

- The reader is presented with a confusing rehearsal of the history of the Hai Rui incident and the involvement of the Ming historian and deputy mayor of Beijing, Wu Han, in the complex prelude to the Cultural Revolution proper (see pp. 525-26);

- The account of how high-school students became involved in the early phase of the Cultural Revolution, and how the crucially important Red Guards came into being, is perfunctory (p. 532);

- The authors claim that teachers and administrators “were selected as the first victims [of the Red Guards] because they were the people instilling culture…” (p. 534). This overlooks the fact that the first victims of the young rebels included some of the rabid Maoist pedagogues who instilled violent and radical ideas in the minds of the young people in the first place. Chang-Halliday remark that “the seeds of hate that Mao had sown were ready for the reaping” (p. 535), failing to acknowledge the existence of a collective enterprise devoted to social engineering, or to appreciate that Mao was hardly the only gardener who tilled the rich field of mass discontent and rebellion;

- The way the writers deal with the fascinating and complex case of Song Binbin, the young woman who famously pinned a Red Guard armband on Mao at the 18 August 1966 mass rally at Tiananmen, is glib (p. 537). Commonplace sources are relied upon and there is no consideration of Song’s view (one that she put on the record for the first time in the film Morning Sun, a full two years prior to the publication of this book);

- Here and elsewhere in the text the authors indulge in unprovable or factually incorrect generalizations such as “there was not one school in the whole of China where atrocities did not occur” (p. 538); or, again, “virtually no new dwellings had been built for ordinary urban residents under the Communists” (p. 541);

- The complex, and fascinating, relationship between Mao and Confucian thought (and indeed the century-long tussle between Confucius and the Chinese intelligentsia) is summarized in what can only be described as burlesque: “Mao did, indeed, hate Confucius, because Confucianism enjoined that a ruler must care for his subjects” (p. 542);

- Etcetera, etcetera, etcetera …

The text of the book is supported by a panoply of devices, presumably employed to assure the reader of its academic authenticity, even though the authors aver that they are writing a popular biography, not a scholastic work. There are sixty-seven pages of footnotes and a large bibliography of books and articles cited in various languages, and archives used. The particular sources for ‘Unsweet Revenge’ cover a wide range: standard works by scholars in the field, the occasional unpublished paper, numerous books and articles produced on the mainland, some by more sober writers, and many issued by what is little more than the gutter press. Added to these are the numerous ‘insider’ interviews which were conducted in many places over many years, and through which the authors have gathered a veritable cornucopia of detail.

A sample of interview citations alone will give the reader some indication of the difficulty that any historian faces when dealing with sources for what is often quite sensational new information. Take the notes on pp. 731-33, for instance. Here we have, among others, an “interview with Mao’s personal staff, 19 Apr. 1999”; “with a local official, 13 Apr. 1996”; “interviews with locals”; “interview with the girlfriend of Mao, 2 Nov. 1995… ”; and, “interviews with many high officials’ children”. Often the source is simply given as an “interview with an insider” followed by a date; or an “interview with a member of Mao’s personal staff”, followed by a date; “interview with an economic manager”, followed by a date. Or, in regard to Li Na, Mao and Jiang Qing’s daughter, and the crucial details of her Cultural Revolution career, information is based on, among other things, “a conversation with Li Na”, an interview “with a colleague”, “interview with a friend of hers who visited her”, “interviews with a friend and former servant”, “interviews with members of Mao’s personal staff”, and “interviews with people close to Mao’s family” (p. 742), with various dates supplied.

All this is fascinating stuff, to be sure, and much may well be credible. However, without providing readers and specialists with more detail, or the wherewithal to verify, crosscheck and interrogate the credentials of these materials, I would suggest that Chang-Halliday seem to be wending their way through a territory profitably traversed by the noted American political biographer Kitty Kelly. Perhaps when the Chang-Halliday archive of interviews (detailing the time and place of interviews, the interviewees’ names and relevance to the subject matter under discussion, with full, not selected recordings, and transcripts, etc.) is opened to public scrutiny, these churlish quibbles will be swept aside.

When considering the authors’ eclectic, and sometimes idiosyncratic, use of sources, in particular Chinese language materials, I believe that we should be mindful of a grand, if not always palatable, tradition of Chinese historical writing, that of waishi 外史, or ‘informal histories’. These are exogenous, non-official, or salacious accounts of the workings and machinations of court politics, or heterodox versions of historical incidents. Such works are also known as yeshi 野史, or ‘stories from the wild’, that is unofficial histories, or baiguan yeshi 稗官野史, which are opposed to or can be contrasted with officially condoned and scripted narratives. The yeshi or baishi have, from their origins, been linked to novelization or semi-fictional accounts. Nonetheless, yeshi have sometimes been used to provide alternative material on events, people and historical moments. Some have even treated them with a measure of credence more usually accorded archival sources. Yeshi accounts of events, while not necessarily of value in the writing of reliable historical narratives, have upon occasion acquired a certain cachet. It is in light of this tradition of Chinese historical writing that, perhaps, Mao: the Unknown Story will gain currency in Chinese, allowing it to enjoy a greater longevity in that language than in English.[8]

As I write this, I unavoidably think of another famous account of Chinese court politics, one that also caused an international sensation when it appeared nearly a century ago. This is The Diary of His Excellence Ching-shan, supposedly an insider’s record of events surrounding the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. [See Lo Hui-min’s The Tradition of China Watching — Watching China Watching (IV) — Ed.]

This work had an inordinate impact on international views of late-imperial China and in particular the life, attitudes and activities of the Empress Dowager, Cixi. However, the Jingshan Diary was a confabulation, a mystification, the product of the fecund imagination of Edmund Backhouse. It is contained in its entirety in the book Backhouse co-authored with J. O. P. Bland (who edited Backhouse’s ‘translation’ of the diary), China Under the Empress Dowager (Heinemann, 1910). The forgery was only uncovered in 1936 (a final, fatal blow, being struck in 1940), after having enjoyed exultant praise in the Western press and long years of influence.[9] The excited international media response to the Jingshan Diary, what Lo Hui-min called “the tidal wave of eulogies”, is worth recalling here:

The popular press led the way in ensuring the book’s success: newspapers and journals in which China had hitherto found no place now rushed into print to hail its appearance. Critics everywhere, not to be outshone by their peers, showered it with extravagant expressions of appreciation, as if no praise were high enough. In a seemingly unending crescendo, readers from Glasgow to Dunedin, from Toronto to Johannesburg, were told that this was “an indispensable guide through the bewildering maze of Chinese politics”; that it was “the most informing book on Chinese affairs that has appeared within a decade”; that it “throws more light on the internal history of Peking than all the books written about China during the last quarter of a century”; that it was “without question one of the most important contributions to contemporary historical literature which has been made in our time”… .[10]

The latest twist in the Jingshan Diary fraud is that you can now buy a classical Chinese translation of the text (one based presumably on the ‘original’ that was deposited in the British Museum) touted by its publisher as being an important yeshi that contains information about the inner history of the late-Qing court.[11]

But as I read Chang-Halliday’s Mao, I was also reminded of another rollicking romp through the workings of a post-imperial totalitarian inner court; an account that describes in great detail the cupidity, cowardliness and bullying of Josef Stalin. Simon Sebag Montefiore’s 2003 biography of the Soviet leader, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), is based on official and personal accounts, and although it dwells on the horrors of a tyrannical regime and indulges in the kind of flip hyperbole familiar to us from the Chang-Halliday screed, the author does at least show what layered depth is possible when archives are trawled in tandem with a careful reading of the correspondence and diaries of key historical figures. With the addition of interviews with family members and a careful attention to the politics of the era he is describing, Montefiore’s Stalin is no less a monster, but his pathology is made clearer to the reader, not obfuscated as is the case with the present text.

Back in China, I would recommend rather the work of a true insider: the treat-and-tell account produced a decade ago by Mao Zedong’s physician, Dr Li Zhisui. Although that text was generated for international consumption, with a gimlet authorial eye trained on the Roderick MacFarquhar rendition of the Maoist era, Li Zhisui and Anne Thurston’s The Private Life of Chairman Mao (Random House, 1994) can be usefully re-read as a corrective to the book under discussion. The Li-Thurston narrative enjoyed the attention of a number of reviewers, including myself, in these pages in January 1996. For all of its faults, and possible lapses of veracity, the Li-Thurston book is an atmospheric account that provides some hint as to the awe Mao inspired, as well as affording some insights into the world he and his fellows created in the sequestered environment of Zhongnan Hai during his years at the helm.

As for the abiding valency of Mao in the popular realm of China, and the need for writers of serious intent to return to him, both in historical detail and through cultural analysis, I still believe that, “Li Zhisui’s book will not alter the fact that Mao is, to many people, EveryMao: he is the peasant lad made good; warrior-literatus as well as philosopher-king … ”[12] Moreover, I would question the contention voiced by a number of prominent reviewers of The Unknown Story, regardless of whether they found worth in the historicity of this account or not, that this book will make any significant contribution to some future, second wave, of Chinese de-Maoification.

The Monkey King

Reading Chang-Halliday’s Mao, one is hard pressed to find any cogent account of Mao Zedong’s own motivations during the first three decades of the People’s Republic (except for the fact that he was a megalomaniac bent on world domination), or why he gained such support then, or continues to enjoy any popular influence today. While Jung Chang has offered a gruesome précis of her findings in media interviews and believes she has gained insights into the workings of Mao’s mind, the reader of Mao: the Unknown Story is faced with little more that a depiction of a pathological ‘evil genius’, a monumental ego with an unbridled lust for power. That is not to say, however, that the authors do not essay some explanation of Mao’s character.

In ‘Unsweet Revenge’ one can glean a hint about Mao’s contradictory political and personal impulses. On page 565 of the book, for example, the writers describe a famous encounter between Mao and Kuai Dafu, the Red Guard leader of the Jinggang Shan Regiment at Tsinghua University (“Mao’s point man” at the institution, p. 549) that took place as Mao Thought Worker’s Propaganda Teams moved on the campus. The leader and the Red Guard firebrand met in the Chairman’s suite in the Great Hall of the People. After introducing Kuai, who was in a highly wrought-up and tearful state, the authors offer the following: “Mao, too, apparently cried, quite possibly out of frustration at his own inability to reconcile his impulses with practical needs”. They then proceed in what for the reader has by now become their trademark clumsy prose to aver that: “The impulse side of Mao wanted the many ‘Conservatives’ he knew were out there to be beaten to a pulp. But the practical side recognised that in his own interest he had to restore order”.

Sadly, even this hard-won observation on the leader’s ambivalent motives is little more than a refraction of Mao’s own famous evaluation of himself. In a letter to Jiang Qing supposedly written on the eve of the Cultural Revolution (and released for internal party consumption following the fall of Lin Biao), Mao remarked that his personality combined a “kingly air” (wangqi), one that demanded to dominate and suborn, with a “monkey spirit” (houqi), that urged him to run riot and throw all into disorder.

As for any of the ideas that motivated the Cultural Revolution, excited so many well-educated young people and inspired the rather particular culture of the era (and yes, whether you like it or not, it did spawn a culture whose roots far predate Jiang Qing’s speech at the February 1966 PLA Forum on the Arts), they are all dismissed out of hand. The Nine Critiques 九評 of the early 1960s that articulated the Chinese Communist Party’s in-principle divergence from the Soviet Union, the long (and admittedly tedious) theoretical essays on culture, the discussions and warnings about the fatal mismatch between the country’s economic base and its superstructure (the legal and educational systems, the arts and the media) that appeared in the press as the expression ‘cultural revolution’ (inspired as it was by political theorists in the Soviet Union of the 1920s) gained currency, and the writings of party theoreticians (virtually none of which are even named), or, for that matter, the activities of Mao’s secretaries (Hu Qiaomu, Tian Jiaying, et al), rate no mention at all.

Chen Boda, a cunning theoretician who wrote many of the key articles in the lead up to the Cultural Revolution, only appears in a cameo role as a co-conspirator, while Zhang Chunqiao, who would come to prominence as a theoretical writer in the 1970s, having promoted the ‘Commune of China’ at a key moment in the early history of the Cultural Revolution, is blithely dismissed. Someone merely possessed of an “ability to churn out articles that dressed up Mao’s self-serving deeds in Marxist garb … Zhang was the person largely responsible for the texts that caused many people in China and abroad to entertain illusions about the true nature of the Cultural Revolution” (p. 575). Thus, in their haste to evacuate entirely ideas, ideology and non-personal motives from modern Chinese history, the authors effectively cut that country off from the twentieth century, except when its leader is dabbling in international power politics, or besting his foreign rivals in infamy by slaughtering his own people.

And what about the ‘banner-bearer of the Cultural Revolution’, Jiang Qing? What of her notorious involvement, first in culture and then in politics during those long years, or that of Lin Biao’s wife, Ye Qun? Why, of course, they both got embroiled in venomous power play because they were not getting enough sex! They took a shine to pitiless revolutionary violence because their concupiscent comrades-in-arms were holding out on them. As the authors opine: “Like Mme Mao, who was also hysterical from frustration, Mrs Lin [sic] now sought compensation and fulfillment in political scheming and persecution, although she was less awful than Mme Mao” (p. 533).

It is hard to know how to proceed at this point. Should I applaud the occasional authorial aperçu, ponder further the validity and weigh up the relative worth of the writers’ archive-based investigations and personal interview ‘revelations’? Should I marvel anew at the ghastly toll of Mao’s personal and ideological rule? Or should I expend myself interrogating every exaggeration, chide each simplification or point out every factual error? Should I just deride the breezy tone of an obnoxious work whose authors glide cockily between knowing self-righteousness and glib journalese? Or, should I instead do my bit as an historian and talk magisterially about the general problems of writing this kind of despot-centered history, one that elides the agency of all others, treats the reader to a snuff-fest of outrages, and yet leaves us none the wiser as to what the hell it was all about?

No One Left to Dance With

…Mao danced on. One by one, as the days went by, his colleagues disappeared from the dance floor, either purged or simply having lost any appetite for fun. Eventually, Mao alone of the leaders still trod the floor.[13]

The part of the book I like the most (although it sports a particularly ungainly title: ‘Nixon: the Red-baiter Baited’, pp. 601-13), and one that sits most comfortably with the authors’ ohmygod style of prose, is that related to the clandestine Sino-American rapprochement. Here we have two autocrats—one effective, Mao Zedong, and the other, Richard Milhouse Nixon, a mere wannabe, along with their cunning enablers, Zhou Enlai and Henry Kissinger—negotiating one of the most dramatic shifts in geopolitical relations. This is readable Realpolitik, comic and grim in turn. The exchanges—all readily available in other sources—are delicious, and the devil dance between the North American superpower and the People’s Republic provide the observer with dialectical delight. It is also the part of the narrative on which I am least qualified to offer an informed opinion.

But when leaders meet sparks may fly. And in Chang-Halliday’s Mao we are presented with the Oriental Despot redux.[14] Page after page Mao careens through plots, counter-plots, ploys, machinations and manipulations, whipping up in his wake his very own Sturm und Drang. The book details a cavalcade of horrors and lies, and the ‘take home message’ of the volume is clarion clear both on the first page of the narration, and in the numerous media interviews Chang Jung has given in relation to the book: “Mao Tse-tung, who for decades held absolute power over the lives of one-quarter of the world’s population, was responsible for well over 70 million deaths in peacetime, more than any other twentieth-century leader” (p. 3).

China becomes thereby something of a world leader in despotic atrocities. But I fear I detect in the sensationalist prose of this book the unmistakable stench of ‘competitive body counting’. There seems to be a certain Schadenfreude at work here, a sense reinforced by such utterly distasteful sentences as: “It was, it seems, a good day if the boss waived a few million deaths” (p. 504). The horror, suffering and deaths of countless numbers of innocent (as well as not so innocent) people can literally shock the mind into numb incomprehension. Even in my personal experience, I well recall the mounting panic, frantic depression and emotional suffocation that I experienced upon encountering dozens of returnees from camps, schools and jails during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and hearing them recount their tales of suffering, loss and death. The deep dudgeon of the authors of Mao: the Unknown Story seems to me, however, to serve ill the memory of the victims of this wretched history, encouraging in the reader an unsettling and breezy lassitude in regard to the origins, scale and meaning of the repeated terrors and their impact on real people, families and communities, a history that still reverberates through the lives of Chinese people today.

Not only do Chang-Halliday bruise the protocols of serious history writing and reinforce, albeit unintentionally, a callousness in regard to the nature and ongoing problems of China’s situation, but they also employ a language that all too readily evokes the image of oriental obliquity. Mao’s colleagues are spoken of as a Court, the Chinese people are his subjects (pp. 337, 500); the mayor of Shanghai, Ke Qingshi, is “a favourite retainer” (p. 515); PLA Unit 8341 charged with the security of Zhongnan Hai is dubbed “the Praetorian Guard” (p. 274ff). Wang Dongxing is the leader’s “trusted chamberlain” (p. 532), and Zhou Enlai his “slave” (pp. 271-72). Even when Mao employs the pronoun of faux party collectivity, the authors claim that, as usual, he is using the “royal we” (p. 589). To emphasize Mao’s rank inhumanity, however, the writers also observe that his “girlfriends were not treated like royal mistresses and showered with gifts and favors. Mao used them, as he did his wife. They provided him with sex, and served him as maids and nurses” (p. 628). Nonetheless, the admix of courtly Victoriana, Claudio-Julian terminology, along with the echoes of China’s own parlance of palace intrigue, leave us with a metaphorical schema that places Mao firmly at some quaint, incomprehensible oriental remove, reducing a complex history to one of personal fiat and imperial hauteur. Although, I should note that there are moments when the terminology of court politics gives way to that of the bestiary: Zhang Chunqiao is “the Cobra” (p. 575) and the ‘Gang of Four’ are collectively described as “Cultural Revolution Rottweilers” (p. 637).

One must wonder whether readers have been presented a Mao tailor-made for the Age of Terror; though on second thought, Mao’s impugned obsession with world domination (vide the long descriptions of this in the section entitled ‘Launching the Secret Superpower Programme’, p. 396ff: “Mao’s determination to preside over a military superpower in his own lifetime was the single most important factor affecting the fate of the Chinese population” [p. 397]) brings to mind a lesser oriental despot, one who is dealt with far more adroitly in another pop culture product.

The creators of South Park, well known for their debunking satires and knowing parodies, gave birth to their own ‘mini-Mao’ in what J. Hoberman writing for The Village Voice called a marionette-driven “equal opportunity offender”, Team America: World Police (Paramount, 2004). The dominant personality in this film is not the group of terror-quelling, butt-kicking hi-tech patriots-on-a-string, ‘Team America’ (fuck, yeah! —as their theme song bellows), nor is it one of the bleeding-heart Hollywood A-B list celebs who are mocked and murdered. Rather, it is the North Korean anti-hero, Kim Jong Il. In one short song sequence in this feature-length spoof, Trey Parker, Matt Stone and Elle Russ manage to create a compelling portrait of a self-pitying and psychologically twisted potentate.

Having dispatched Hans Blix, the UN weapons inspector, in his wide-screen-size shark tank, the diminutive dictator wanders through the corridors of his socialist kitsch palace. Moving past frescos of banner-bearing workers rushing towards a communist future, and then by a display case of action figures, Kim is shown lying mournfully on a capacious bed. Finally, he appears at the end of a corridor dominated by a portrait of his father, Kim Il Song, framed by a moon gate.

All the while Kim the Younger sings his own version of ‘I’m So Lonely’.

I’m so ronree, so ronree,

so ronree and sadree arone.

I have no one, just me onree,

sitting on my rittle throne.

I work very hard, and make a great friend

But no body ristens, no one understands.

Seems rike no one takes me seriousree

And, so, I’m ronree,

A bitter ronree, horrid old me.

Source:

This review-essay originally appeared in The China Journal, No.55 (January 2006): 128-139. It was also reprinted in China Digital Times, 26 April 2006 and it was included in Was Mao Really a Monster: The Academic Response to Chang and Halliday’s “Mao: The Unknown Story”, edited by Gregor Benton and Lin Chun (London, New York: Routledge, 2010). It is also included in Watching China Watching, a China Heritage series.

‘I’m So Ronree’ was one of four essays on the Chang-Halliday Mao published by The China Journal. It focussed on the material in that book related to the Cultural Revolution. In their reviews colleagues addressed different aspects of the book. They are:

- Gregor Benton and Steve Tsang, ‘The Portrayal of Opportunism, Betrayal, and Manipulation in Mao’s Rise to Power’, The China Journal, no. 55 (January 2006): 95-109;

- Timothy Cheek, ‘The New Number One Counter-Revolutionary Inside the Party: Academic Biography as Mass Criticism’, The China Journal, no. 55 (January 2006): 109-118; and,

- Lowell Dittmer, ‘Pitfalls of Charisma’, The China Journal, no. 55 (January 2006): 119-128.

***

Notes:

[1] Geremie R. Barmé, Shades of Mao, the posthumous cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1996).

[2] Jiang Zemin, “Zai Mao Zedong tongzhi danchen 100 zhounian jinian dahuishangde jianghua (1993 nian 12 yue 26 ri)” [Speech on the occasion of the centenary of Comrade Mao Zedong’s birth], Renmin ribao, 27 December 1993; and Barmé, Shades of Mao, p. 259.

[3] Hu as reported in the Xinhua News Agency release dated 26 December 2003, “Zhonggong zhongyang juxing jinian Mao Zedong tongzhi danchen 110 zhounian zuotanhui” [Symposium held on the occasion of the 110th anniversary of Comrade Mao Zedong’s birth].

[4] Li Jie, “The Mao Phenomenon: A Survivor’s Critique”, in Shades of Mao, p. 141.

[5] Op. cit., p. 143.

[6] I would note in passing, however, that given the use of powerful “moral-evaluative” terminology in Chinese historiography, the Chang-Halliday book will read more “naturally” in Chinese translation. On the importance of moral-evaluative language in modern Chinese, see my In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), pp. 326-28.

[7] Morning Sun (Boston: Long Bow Group, 2003). For the related website, see www.morningsun.org

[8] See also Linda Jaivin’s “Wild History”, a review of Mao: the Unknown Story published in The Bulletin, 9 August 2005.

[9] See Lo Hui-min, “The Ching-shan Diary: a clue to its forgery”, East Asian History, No. 1 (June 1991): 98-124. The diary and its notoriety resonate with the advent and influence in the early years of the new century of The Tiananmen Papers.

[10] Lo, “The Ching-shan Diary”, op. cit., p. 104.

[11] See Yun Yuding, Jingshan, et al, Guangxu huangdi waizhuan, Jingshan riji, [An informal biography of the Guangxu emperor, Jingshan diary] (Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe, 1998), published in the series Qingmo baishi jingxuan congshu [Selected informal histories from the late Qing]. In fact, the fake diary was accepted by communist writers cum-historians like Deng Liqun in the 1940s, so the present ‘recuperation’ of the work in China has a history of its own. See Lo, “The Ching-shan Diary”, p. 112, n. 71.

[12] Barmé, “Private Practice, Public Performance: The Cultural Revelations of Dr Li”, The China Journal, No. 35 (January 1996), p. 126.

[13] Chang and Halliday, Mao: the Untold Story, p. 546.

[14] As Voltaire wrote of the ‘despot’: “Now, the emperors of Turkey, Morocco, Hindustan and China were called despots by us; and we attach to this title the idea of a ferocious madman who heeds only his own whims”. Quoted in Alain Grosrichard, The Sultan’s Court: European Fantasies of the East, trans. Liz Heron (London: Verso, 1998), p. 32. My thanks to Adam Driver for bringing this work to my attention.

***

Recommended Reading:

- Geremie R. Barmé, Private Practice, Public Performance: The Cultural Revelations of Dr Li, The China Journal, No. 35 (January 1996): 121-127

- Geremie R. Barmé, Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1996

- Jeremy Brown and Matthew D. Johnson, eds, Maoism at the Grassroots: Everyday Life in China’s Era of High Socialism, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015

- 高華, 有關毛澤東研究的幾個問題, 2002年10月18日講演錄

- 高華, 紅太陽是怎樣升起的: 延安整風運動的來龍去脈, 香港中文大学出版社, 2000

- 高華, 歷史筆記, 2 vols, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2014

- 高華,毛澤東何以發動文革?, 7 April 2006, YouTube lecture

- 高華,再探林彪事件, 7 April 2006, YouTube lecture

- Sebastian Heilmann and Elizabeth J. Perry, eds, Mao’s Invisible Hand: The Political Foundations of Adaptive Governance in China, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011

- Dieter Heinzig, The Soviet Union and Communist China 1945-1950. The Arduous Road to the Alliance, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2004

- Jie Li and Enhua Zhang, eds, Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2016

- Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2006 (see the review appended below)

- Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine, Mao: The Real Story, Simon & Schuster, 2012

Uncivil War

Geremie R. Barme

This review of Mao’s Last Revolution by Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Belknap Press/Harvard University Press 2006, appeared under the title Uncivil War in The Financial Times, 26 August 2006. — Ed.

***

On August 18 1966, Mao Zedong reviewed a mass gathering of zealous young people in Tiananmen Square. At the last moment, he donned a People’s Liberation Army uniform and, although it didn’t quite fit his bulky frame, it marked both to his audience of more than a million Red Guards and to his colleagues standing on the rostrum with him, that the old guerrilla leader was launching a new campaign. It would become a war of all against all, a civil conflict unlike any other that China had experienced.

In China, August 1966 is known as Red August — hong bayue 紅八月. For the supporters of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, red symbolised revolution and the ardour for uncompromising and radical change. For them the slogan of the day was “rebellion is justified”. But for those who were the victims of the opening salvos of that political movement, the harrowing weeks of verbal abuse, ransacking and murder made it “bloody August”. It was but a prelude to the long years of confusion and devastation that were to follow.

Mao’s Last Revolution is the product of years of research and reflection by two prominent scholars of China’s communist-era politics, Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals. Both had close encounters with aspects of the Cultural Revolution — MacFarquhar travelled to China and early on offered prescient analysis of the politics of the day; Schoenhals studied at a late-Maoist university. Like other foreigners who experienced China then, as well as countless Chinese, they were engrossed by the events of those years. For decades they have both pursued their interest, following the gradual revelations of participants, ferreting out internal documents and personal accounts in an effort to make sense of what happened over many years of writing.

This book is a meticulous rendition of elite Chinese revolutionary politics. It supplements MacFarquhar’s voluminous studies of the origin of the Cultural Revolution, and like his other works the detailed depiction in this book is judicious and painstaking. It is an account that puts other recent works on Mao’s grand revolution in the shade — one thinks in particular of Jon Halliday and Jung Chang’s bestselling “maledictory” on Mao [see above — Ed.].

Mao’s Last Revolution will be essential for students of the denouement of the Chinese revolution. However, this tome is not for the general reader. And while the authors are savvy connoisseurs of power politics, their work provides scant insight into the broader world of high-Maoist China.

It is frustrating that the authors give so little weight to the underpinnings of Mao’s last revolution; nor do they help the reader gauge the origins or extent of pent-up mass fury. On the ground, beyond the corridors of power, there was great popular resentment towards the socialist state’s callous rule. The party’s arrogant elitism, its entrenched system of privilege and the yawning gap between its high-minded rhetoric and day-to-day reality, all fed into a frenzy that not only created “bloody August”, but also eventually saw the country awash in blood.

The authors have their eyes set on elite infighting, and they traverse their chosen battleground with a staunch gait. It is a dour journey they make, one only occasionally relieved by touches of (gallows) humour, although humour — black rather than red — is a common feature of Chinese accounts of this wretched era. So, for example, it is a relief to encounter the authors’ comment on the murderous antics of the opportunistic Wang Li: “But if Wang was trying to jump on the bandwagon, he found that he had landed on a tumbril instead.”

For insightful and elegant writing on the Cultural Revolution, however, the work of Simon Leys (pen name for Pierre Ryckmans), the Australian-based Belgian sinologist, has yet to be surpassed. It is therefore surprising that, while many other non-Chinese accounts (some quite dodgy) are quoted in Mao’s Last Revolution, the remarkable books by Leys such as The Chairman’s New Clothes (1971) and Chinese Shadows (1975) are ignored.

Mao’s Last Revolution ends with the authors expressing their magisterial hope that, at some unspecified time in the future, a democratic China will confront the full history of this period and the legacy of Mao Zedong. In today’s post-socialist China, however, it is already evident that the Chairman and his history are so intermeshed with that country’s identity that perhaps even democracy will fail to exorcise his shade.

With increasing social unrest and popular outrage at the party-state’s corruption, it is probably too early for the masses to relegate Mao’s call to rebel to the dustbin of history. As a former Red Guard, now a successful businessman in Beijing, remarked to the oral historian Sang Ye 桑曄:

“If you ask me to look back on it from my present perspective, I don’t think it was all that different from today. If a time comes when rebellion is justified again, I might be too old to get involved, but believe you me I’m going to encourage my son to get out there and fuck them over a bit.”

‘I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end.’

ἐγὼ τὸ ἄλφα καὶ τὸ ὦ, ὁ πρῶτος καὶ ὁ ἔσχατος, ἡ ἀρχὴ καὶ τὸ τέλος.

***

’They congregate en masse. In front of each of them is a text that is, word-for-word, the same as the speech being read out to them by the leader and which they, in turn, dutifully transcribe in longhand.’

… 成百上千人在一起開會,每人手裡都拿著一份文件,並且與領導正在念的文件是一模一樣的,一字不差,但是幾乎所有人都在領導念文件的同時拿筆在本上認真記錄。

車軲轆話畢