Contra Trump

勝利萬歲!

Fascism … is more of an energy than an ideology. It does not communicate through the mind. It is pumped into the heart and enforced by the fist. It is intellectually vacuous and constantly shifting.

… fascism appeals to some of the darkest instincts of human nature, the hatred of difference, the yearning for order, the sublimation of the individual to the group, the enchantment of violence.

— from Fascism: The Story of an Idea

In T2 – A Feature, Not a Bug, a chapter in our series Contra Trump & America’s Empire of Tedium that was published on the eve of the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 47th President of the United States of America on 20 January 2025, Chris Hedges offered the following stern assessment:

President-elect Donald Trump does not herald the advent of fascism. He heralds the collapse of the veneer that masked the corruption within the ruling class and their pretense of democracy. He is the symptom, not the disease. The loss of basic democratic norms began long before Trump, which paved the road to an American totalitarianism.

Commentators are wary of such terms as ‘fascism’ and ‘totalitarianism’, particularly when they are applied to their own societies. China Heritage is not so squeamish. See:

***

Origin Story is a podcast series by the English writers Ian Dunt and Dorian Lynskey. Episodes focus on a word, idea or figure from history, explore its origins and talk about how it influences political discourse today. Since launching the series in May 2022, Dunt and Lynskey have covered such topics as culture war, neoliberalism, freedom of speech, eugenics, climate change denial, anti-vaxxers, Zionism, gaslighting, the war on drugs, the Illuminati and the politics of zombies, and profiled the likes of Winston Churchill, Ayn Rand, George Orwell and Elon Musk.

In response to Trump’s inauguration, the celebrations surrounding it, the performance of Elon Musk and the flurry of Executive Orders that Trump signed on 20 January 2025, Ian Dunt and Dorian Lynskey published an extemporaneous episode of Origin Story in which they revisited the theme of ‘fascism’. Below, following a transcript of their remarks, we feature an excerpt from Fascism — The Story of an Idea, a book-length account of a topic in Origin Story.

We would also encourage readers to refer to an earlier chapter in the present series titled Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?; as well as, Elon, I love you. Signed China.

***

My thanks to Phillip Adams, friend and Australian cultural paragon, who introduced me to Ian Dunt’s work, wit and wisdom.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 January 2025

***

Origin Story Archive:

Top Ten Episodes of Origin Story:

Origin Story Books:

***

The Last Sunday

Remember this America: flawed yet remarkable, filled with cruelty and compassion, selfishness and selflessness, folly and genius. Remember that this nation’s principles, values, laws, Constitution, and history—imperfect at its founding—still bound and blessed us to a slow but steady climb toward a better nation.

Remember America, which weathered upheaval, conflict, and calamity in every generation, only to rise again. Recall the America that saw liberty, freedom, human dignity, and equal justice as aspirations worth praising rather than mocking.

Remember an America almost unique in its capacity to balance entrepreneurial ambition with the understanding—however begrudging at times—that extending a helping hand to the needy makes us stronger, not weaker.

Hold this vision tight because come noon on Monday, the war to erase that America begins.

— Rick Wilson, 19 January 2025

***

Trump swore to uphold the Constitution in January 2017. He violated that oath in January 2021. Now, in January 2025, he will swear it again. The ritual survives. Its meaning has been lost.

— David Frum, 14 January 2025

***

It was like watching Larry Flynt get elected pope.

— David Brooks on T1, 19 January 2025

I can’t prove you are a fascist But when I see a bird that quacks like a duck, walks like a duck, has feathers and webbed feet and associates with ducks—I’m certainly going to assume that he is a duck.

— reworking of a line by Emil Mazey, secretary-treasurer of the United Auto Workers, in 1946 (the original quotation referred to communists)

- Ryan Mac, Elon Musk Ignites Online Speculation Over the Meaning of a Hand Gesture, The New York Times, 20 January 2025

- Alan Herrera, Neo-Nazis Celebrate Elon Musk’s ‘Nazi Salute’, Comic Sands, 21 January 2025

***

… you have to fight hard to avoid the F word. You have to put really concerted effort into finding ingenious ways of distinguishing this movement from the historical antecedents which explain it. You have to perform contorted intellectual gymnastics to avoid the one word which explains the phenomenon we see in front of our eyes.

— Ian Dunt, Look at Musk’s salute in context and you can see the future of the US, inews, 23 January 2025

Can we call it fascism yet?

Ian Dunt & Dorian Lynskey

We wrote our Origin Story book about the past and present and possible future of fascism before the American election. And I’ve thought about it quite a lot since the American election. Following the inauguration of Donald Trump for the second time, first was an accident, second looks like carelessness.

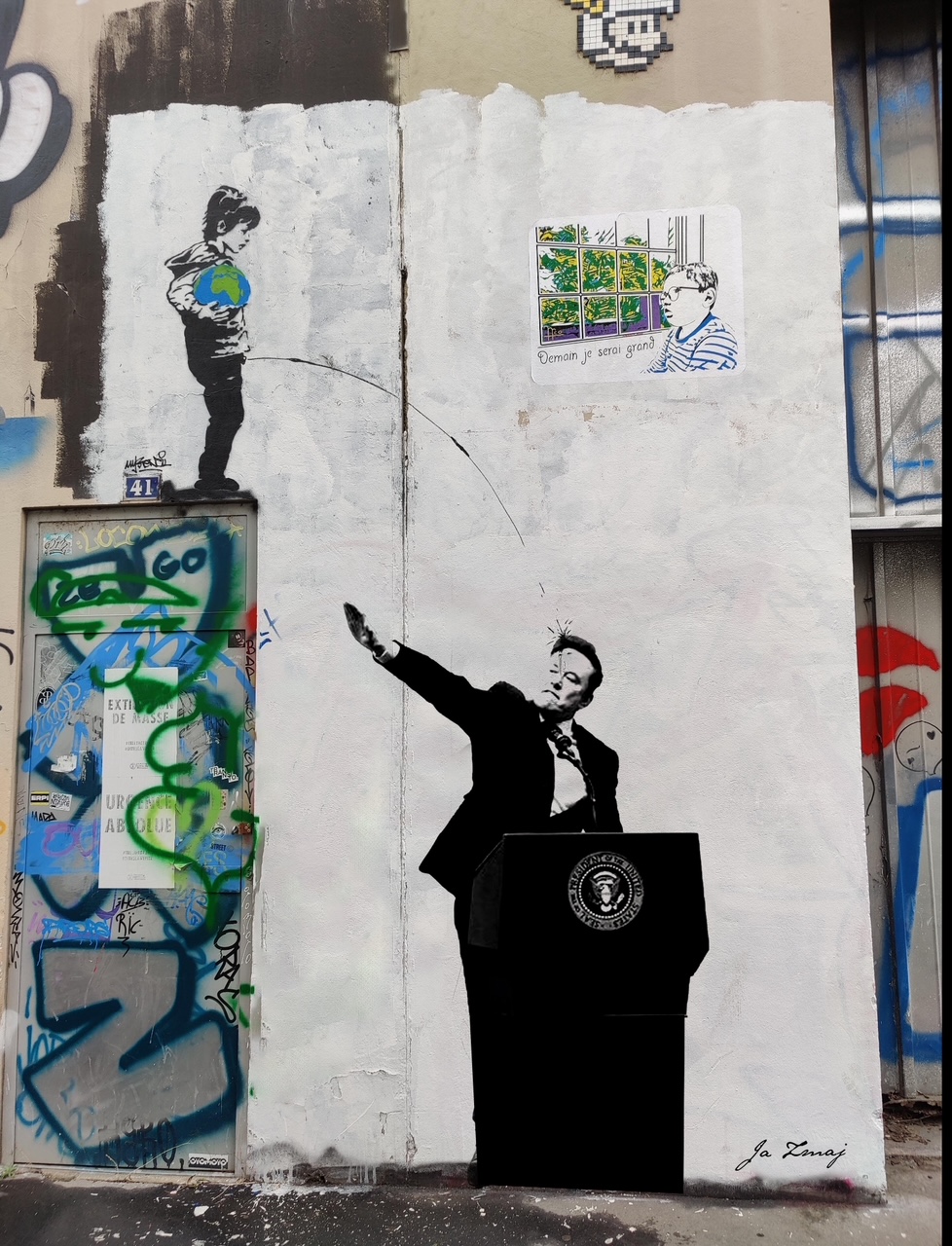

We will be releasing a little extract from the book, a bit from the prologue [see below — Ed.], because I do think that the history is quite useful in spotting some of the patterns and symbolism. Although it has to be said that Elon Musk throwing what appears to be a fascist salute more than once, doesn’t require the historian Richard J. Evans to decode that one.

Ian, obviously, one does not like to be hysterical about this. We were talking about how not to cry fascism and everything. What did you make of the inauguration?

Oh, I would really like to cry fascism now. … I know that you’ve discovered that apparently the frog’s in water and its bollocks, and apparently the frog does jump out of the water. But you do sort of feel like, because it’s like an everyday sort of degree by degree by degree increase, you feel trapped by it. And there is a point where you have to take a step back, or deal with, I mean, I could do all of this list with Trump, obviously, but you have to do it with Musk.

Which is like just over the last couple of months. This is a guy that is explicitly telling people, go out and vote and support Tommy Robinson, Alternative for Deutschland, extremist, street thugs. These are the people he’s supporting. He’s interacting with far-right accounts. He’s using all of the modern day online far-right imagery, Pepe the Frog and all of his nonsense monikers that he’s adopted.

The accounts that he interacts with, the conspiracy theories that he spreads, they’re all on the far right.

So then when he gets up and repeatedly does something that looks like a Nazi salute, like if that was someone else, if it was George Bush who did it, you’d think like, oh, he just got that all funny and it came out weird and don’t be weird about it. But it takes so much generosity that you have really reached the point of being fundamentally irrational to not interpret it in this way given the series of actions that led up to it. Years ago, when we did our episode on fascism, we were like, you need the alarm to be pulled when things get really sketchy.

Well, to me, honestly, yesterday, that’s what really sketchy looks like.

It could be like a genuine gesture. It could be a edgelord thing like the ironic fascism, which always ends up being like real fascism. Or it could genuinely be like just a terrible, unfortunate mistake.

But if it was the latter, then you would immediately come out and you put out a statement considering that he posts to X a bazillion times a day and go, I’m mortified. Obviously, I was just trying to express my sincere passion for making America great again. And it came out and resembled this.

You would apologize, as people did, as David Bowie did, it was like 50 years ago.

When he did things, he was going, Oh God, no, I know he looks really bad, and I was waving and did it. But he’s not doing that.

So it’s very hard to understand why somebody would consciously do a Nazi salute when we’re used to a certain amount of plausible deniability. And yet there’s really nothing in his behaviour to indicate that it would not be or that it was not. And I’m worried in a sense that it is a distraction from the slew of toxic executive orders that Trump has issued on that day.

Yeah. But the thing is, those executive orders are part of the same story. Because again, if there was a different political project with less obvious overtones of fascist parties in the past, you wouldn’t feel so tempted to ascribe the worst possible interpretation to this gesture.

But because actually it contains really obvious echoes of the past, you think, well, I mean, we sort of feel like we’re well within our rights to do it. The political program, as far as we’ve seen it so far, and this is a mixture of the stated aims, the executive orders, is expansionist in terms of territory in a way that Trump wasn’t in his first term. You know, this is really, I mean, you could almost, part of the stuff he says about things, you know, like Canada or like the Panama Canal, it’s basically lemon scrum.

It’s basically like living space [i.e., Lebensraum — Ed.]. We need more living space for America. You know, these constantly expanding frontiers that we intend to have.

You know, it targets minority groups, in this case, trans people, in the most vindictive, aggressive way imaginable. It comes, by the way, with this rhetoric around this kind of, what is it? It’s this sort of resurrectionist, quasi-religious, almost theological rhetoric. You know, this idea of like, well, I nearly died, but God intervened to save me. I’m here as part of the rebirth of the nation. Like Mussolini, when Mussolini was almost assassinated. Yeah.

Again, almost word for word. It’s not just that the same policies are being pursued or that the same tactics are being pursued. It’s that the same rhetoric is being used. It’s that the same symbolism is being engaged. I mean, how many things do we need to check off the box before we go, well, this just looks like exactly the same fucking thing.

Well, this is why I think the whole debate has changed a lot. The first term debate about Trump and fascism, and then January the 6th, I think we agree. In the book, we’re making the point that actually, if you’ve got street violence, that really changes things, more so than Charlottesville, more directly tied to Trump than Charlottesville.

Then what happened basically after we filed the book, and we were still tinkering with it as late as we could, but there comes a point where they go, just please stop now, the book is finished. Then all these things came out about former cabinet members going, oh, I think he’s a fascist. The assassination and the way that he framed that, in pretty much exactly the same way that Mussolini did.

And then, like I said, Musk becoming more and more openly far right. And these things kept happening and they kept almost like removing those things that even Trump’s fiercest critic would have to go, look, he is not interested, as Hitler was, in territorial expansion. And he was just like, oh, I’m sorry, I neglected to tick that box. I’ll get on it now.

And then pardoning the January 6th protestors, including many that were involved in violent crime and beating the police. And just, oh, right, no, okay, this is an endorsement for violence, which of course is again what Mussolini did, which is that he pardoned or maybe didn’t use that term. But there was an amnesty for fascists who had been convicted of street violence in the build up to him taking power in ’22. So it’s sort of quite hard to actually go out of your way to just go, here are the ways in which Trump diverges from historic fascism. It’s very, very hard because he keeps … ticking off those boxes that he had neglected before. Why would you argue that it isn’t? And there’s so many people that are going out of their way to normalize this. And I know that there was definitely normalization. You know, we quote The New York Times talking about Hitler and which just goes, oh, he’s reasonable now. But there was literally a piece in The Economist about, well, here’s how Trump could buy Greenland.

I know. Oh my God, I know.

[Note: See An American purchase of Greenland could be the deal of the century, The Economist, 8 January 2025.]

And you’re like, what the fuck are you doing? It’s sort of like, well, you know, here’s the best way for Hitler to take the Sudetenland. So the normalization blows my mind as well, because it almost seems like the worse that Trump gets, the worse the things he is saying and planning to do, the more compulsion there is among the mainstream media, which I do not generally use as an insult, but you know, among the mainstream media, to sort of go, well, I guess if the president’s doing this, we must find a way of making it seem like it’s somehow a reasonable thing to do.

A hundred percent. You know, you and I were chatting on the phone yesterday about the BBC’s coverage. And it’s not like they don’t have the ability to just go out and go, look, he’s a fascist that tried to overthrow democracy and now he’s become president.

I kind of get it. That’s not a BBC headline. But there must be some effort to communicate the fact that this is not normal. Or within the reasonable bounds of liberal democracy. … If you have a former president having to preemptively pardon people who try to protect democracy because of the next guy coming in, you have to be able to communicate to your viewers, to your readers that this is a very, very acute, dangerous situation. That is just simply not fucking happening.

The coverage that I see is astonishing in its normality. I mean, just kind of, just so dangerous in its normality. And then that argument that you’re making there about creating this kind of almost realistic case for the unrealistic things that he proposes.

I mean, I just saw the same in Tortoise Media, this sort of account of like, well, actually, you know, he just has this way of making things possible. I mean, it’s, it’s, you know, against the US. Constitution. This particular item was on citizenship. But, you know, just by virtue of saying it, he sort of makes it possible. And you’re like, are you just going to do all of this fucking work for him?

Yeah.

If this is the tenor that you’re going to adopt towards this and say, it’s almost like you’re going to, instead of launching even the remotest challenge against him, your job is just simply to construct the world according to his whims, so that your readers can then ingest it in that manner and tolerate the changes he makes when he tries to approach them. It really is a frankly staggering state of affairs.

Well, I heard Justin Webb on his program in Washington, and he went from interviewing a hardcore Trump supporter that was saying that all illegal immigrants should be deported, even people who have been here for many years and have had children and built lives here. Then he went and I was like, well, I guess it’s probably going to go to somebody now who is like going, why this might be bad? And then he goes to a Republican to explain how this might work.

And I don’t want to be over dramatic, but it’s a little bit like interviewing like a kind of an early Hitler supporter about saying how they think that you should take away the Jewish businesses and bar them from various jobs. And then you follow that by going to a Nazi official and going, well, so how would you go about this? Like it’s obviously not yet as extreme as that.

But one of the things that we came across in the book, it’s more obvious with Mussolini, was just a tremendous amount of praise and just like normalization, he’s really shaking things up and he’s really getting things done and Italy was a bit of a mess and this needs sorting out. This went on for years and years. Now that is largely because Mussolini was not targeting minorities.

He was definitely talking to his political enemies and people seem to think, well, they’re communists, so who cares? Seemed to be the general attitude internationally. But there wasn’t that horror that accompanied the Nazi persecution of the Jews. But even then in the early years of Nazism, there was a lot of, here’s a guy with some strong opinions, let’s hear him out. I think where the historical perspective is useful, is that we look back on fascism with this abhorrence and think, well, all people of goodwill and mainstream media organizations must have recognized this for what it was. They didn’t really, and they did quite a lot of making excuses until one could no longer make excuses.

Similarly, we look back at people who joined or voted for the Muslim East Fascist Party or the Nazi Party with some finger wagging, I would say. I do think that we are prepared to blame those people for the decisions that they made. And yet when it’s in the present, it’s seen as a bit taboo.

It’s like, well, this is the American people and this is what they voted for. So let’s take seriously their concerns and people go, well, you can’t attack Trump supporters because you’ve got to win them back. But Jimmy [Webb], I personally don’t have to win them back. That’s not my job. You know, and you think, well, hang on, you know, let’s try and think, like let’s try and use this historical lens. And it’s like, you don’t have to suspend condemnation.

You don’t have to normalize in the present. And yet this is what is going on. And I really think that there should be more voices on the BBC and elsewhere and indeed in the American channels explaining why this is extreme and bad and that it’s okay to do that even if Trump won the election.

Like you don’t have to kind of just go, well, I guess the American people want the extreme bad thing, so it can’t be extreme and bad anymore. …

***

Ein Hitlergruß ist ein Hitlergruß ist ein Hitlergruß

— Elon Musk streckt den rechten Arm, und alle springen drüber. Willkommen im neuen Aufmerksamkeitsregime.

— headline of an opinion piece by Lenz Jacobsen, Zeit Online, 21 January 2025

***

For Americans citizens, Jan. 20, 2025, is Liberation Day.

— Donald J. Trump, US president

***

What is fascism?

Introduction to Fascism: The Story of an Idea

The problem with writing about fascism is that no one can say precisely what it is. There are two versions of it in the popular imagination. The first is vivid and monstrous, a journey to the furthest possibilities of human evil. Adolf Hitler barking out violent fantasies from a podium. Benito Mussolini glaring at an adoring crowd. The murder factories. The uniformed thugs. The mechanization of man.

The second is broad, shallow and ubiquitous. It’s a cheap insult we throw around anytime we come across someone with a whiff of the authoritarian, the overbearing politician, the dogmatic activist, the busybody, the ticket inspector. The word fascism therefore leads a double life. It’s serious and frivolous, existential and glib. And then, when you peer more closely, it threatens to disintegrate altogether. Scholars don’t even agree on what fascism meant between 1922 and 1945, let alone what it might mean today.

Arguments about who is and is not a fascist are now so mainstream, they informed a joke in Greta Gerwig’s billion-dollar 2023 blockbuster Barbie. When Margot Robbie’s Barbie ventures into the real world, a surly high schooler calls her a fascist. “She thinks I’m a fascist”, Barbie protests. “I don’t control the railways or the flow of commerce.”

Confusion is inevitable because fascism has no clear-cut intellectual basis. Most major political ideologies have a hefty theoretical grounding based on the work of great thinkers. Conservatism has Edmund Burke, liberalism has John Stuart Mill, socialism has Karl Marx. But fascism is not a coherent ideology. Mussolini’s The Doctrine of Fascism was an extended encyclopaedia entry, published 13 years into fascism’s lifespan, while Hitler’s Mein Kampf was a deranged screed of personal grievances and prejudices.

While Joseph Stalin agonized over proving, however dishonestly, that his actions conformed to Marxist and Leninist doctrine, fascist leaders didn’t bother justifying themselves at all because there was no doctrine to follow. Fascism, then, is more of an energy than an ideology. It does not communicate through the mind.

It is pumped into the heart and enforced by the fist. It is intellectually vacuous and constantly shifting. When the term first appeared in Italy in 1919, fascism short-circuited conventional assumptions about the political spectrum.

It combined the ancient and the modern, mysticism and bureaucracy, left and right, the mob and the machine, in unprecedented and sometimes inexplicable ways. “Whichever way we approach fascism”, wrote the Spanish philosopher José Artega y Gasset in 1927, “we find that it is simultaneously one thing and the contrary. It is A and not A.”

Yet the paradoxes of fascism are a strength rather than a weakness. It weaponizes its contradictions to maximize both its appeal and its freedom to act as it wishes. There is therefore no such thing as a pure version of fascism.

People have been arguing about the nature of fascism since at least 1922, when Mussolini became Italy’s prime minister, and they’re still arguing about it now. They use the word in two distinct but connected ways. The first is a description of a historical movement, and the second is a contemporary warning about what might happen next.

The historical approach presumes that fascism can only be understood in retrospect, based more on what fascist regimes did than what they said. But even this does not achieve total clarity. Each fascist party around the world behaved in strikingly different ways.

The two most prominent and successful fascist movements in Italy and Germany had as much that divided them as united them. Even within each country, fascism was a shapeshifter whose self-image did not align with its actual conduct. Fascist leaders wanted the world to see their societies as great coordinated machines working in perfect unity. But in reality, they were chaotic, messy compromises, riven by internal tensions and rivalries. Many of fascism’s aims evolved according to whatever was most convenient at the time. It was fluid, opportunistic and contradictory.

The body of scholarly work on fascism is therefore incapable of consensus. The most prominent thinkers on the subject, including Robert O. Paxton, Roger Griffin, Zeev Z. Sternhell and Stanley G. Payne, have been trying for decades to come up with a watertight definition. But every proposal has been either too narrow or too broad.

Other writers have attempted to address fascism’s inconsistencies and absences by compiling these checklists of characteristics. But they’re just as unsatisfactory. The Oxford English Dictionary‘s definition is accurate, but incomplete:

An authoritarian and nationalistic system of government and social organization, which emerged after the end of the First World War in 1918, and became a prominent force in European politics during the 1920s and 1930s, most notably in Italy and Germany; (later also) an extreme right-wing political ideology, based on the principles underlying this system.

Another problem for historians, though not the world, is that we didn’t get to see how fascism might have evolved if it had not self-immolated in the furnace of war.

Perhaps Hitler and Mussolini might have died in their beds decades later, like Spain’s General Franco or Portugal’s Antonio Salazar, their regimes having degraded into more conventional authoritarian dictatorships, or perhaps fascism was inherently so unstable that it would have devoured itself in some other way. Even during the lifetimes of Hitler and Mussolini, the word roamed wildly. In 1936, the anti-fascist American journalist Dorothy Thompson complained that “the far left … stupidly label everybody who does not agree with them fascists.” In his 1944 essay, What is Fascism?, George Orwell remarked that he had heard the word applied to not just political factions, but “farmers, shopkeepers, social credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, ball fighting, the 1922 committee, the 1941 committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-shek, homosexuality, Priestley’s broadcast, youth hostels, astrology, women, dogs, and I do not know what else.”

Fascism’s incredible messiness allows for partisan mischief. Bad faith actors simplifying history to make points about present day politics and assign all the blame to their enemies. Conservatives pounce with glee on fascism’s debt to socialism, while leftists focus on the complicity of conservatives. Both camps are engaged in ignoring inconvenient facts. German and Italian fascists themselves claim that they had transcended traditional notions of left and right. The contemporary approach is to reduce the emphasis on historical details and instead treat the word fascism as a red alert, a clarion call to democrats that something especially malign and dangerous is taking place.

It means we’re less interested in explaining what happened in Europe a century ago than in identifying warning signs about what might take place in the future. The goal is to raise the alarm in the spirit of the old antifascist slogan, “never again”. This is often done sloppily without any serious engagement with how fascism truly functioned. It can sometimes seem as if only the emotive label fascist can signal sufficient concern, as if calling a politician a far-right ethno-nationalist authoritarian is somehow not taking them seriously enough. In the words of fascism expert Roger Griffin, you can be a total xenophobic racist male chauvinist bastard and still not be a fascist. Sometimes this is done cynically, as an attempt to associate whichever group you don’t like with the moral horror of fascism’s worst crimes. Christo-fascism, Islamo-fascism, eco-fascism, woke fascism, even liberal fascism. As a result, the word is typically more of an insult than a diagnosis. Each time it’s used in this way, it loses some of its power.

These arguments became much more urgent and mainstream with Donald Trump’s shocking ascendancy to the White House in 2016, which propelled him into an international brotherhood of authoritarians, alongside the likes of Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Hungary’s Viktor Orban. As the democratically elected candidate of one of America’s two major parties, Trump was no 1930s style fascist. But his rhetoric, policies and bullish contempt for democratic norms, culminating in his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, nudged his administration closer to fascism than any in the country’s history.

President Joe Biden, not a man prone to hyperbole, later described Trump’s Make America Great Again MAGA movement as ‘semi-fascist’. The specific circumstances that birthed fascism between the two world wars no longer exist, but the energy that drove it does. All around us, we can see an obsession with national rebirth, the demonization of enemies, and the channeling of material anxieties into violent, irrational, conspiratorial, apocalyptic movements.

It’s that dark blood magic that distinguishes fascism from conventional hard-right governments. As new books about fascism and the fragility of democracy filled the shelves during the Trump administration, some anxious readers revisited old ones, such as Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and It Can’t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel about an American fascist takeover. While it’s dangerous to meet complacency with hysteria, it is important to remember that something akin to fascism can always happen here.

No country is inherently immune. No electorate is so sophisticated that it cannot become vulnerable to fascism’s psychological temptations. As the Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Reich wrote in 1933, “there is not a single individual who does not bear the elements of fascist feeling and thinking in his structure.”

This, then, is the moral lesson of the story of fascism. It’s not necessarily about precise definitions or watertight checklists or strictly policed usage. It’s about recognising that fascism appeals to some of the darkest instincts of human nature, the hatred of difference, the yearning for order, the sublimation of the individual to the group, the enchantment of violence.

At heart, Orwell suggested, fascism meant something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist. Almost any English person would accept bully as a synonym for fascist. The story of fascism shows us what happens when these instincts are given free rein and reach their ultimate expression.

It therefore serves as a reminder to treat with extreme vigilance any individual or group that seeks to encourage those ideas and to dedicate oneself to stopping them. The first step in that process is to understand where fascism came from. This book will tell its origin story.

Rather than join the long fruitless hunt for a perfect definition, we will explain what happened, how it happened and why. Only then will we try to understand what fascism means and what form it might take in the present day. The story begins in the strangest of ways with a motley crew of nationalists, anarchists, socialists, artists, war veterans and cranks in Italy, in 1919.

***

Source:

- Ian Dunt and Dorian Lynskey, Trump’s inauguration: Can we call it fascism yet?, Origin Story, 21 January 2025.

***

Contra Trump

& America’s Empire of Tedium

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

- An Elegiac Eulogy from Unf*cking The Republic

- The American Green Zone in Our Consciousness

- Those 107 Days

- ‘I Think I’m Gonna Hate It Here’ — Randy Rainbow introduces the clown-car cabinet of MAGADU

- 6 January 2021 to 6 January 2025: America’s Slow-burn Autogolpe

- T2 – A Feature, Not a Bug

- Trump’s Inauguration — Can we call it fascism yet?

***

***

So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish!