In 2015, I contacted Ai Weiwei, then under house arrest in Beijing, to ask if I could exhibit his work on a remote island in the Salish Sea. To my amazement, he agreed. The resulting exhibition, Ai Weiwei: Fault Line, included work related to the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. During the earthquake 5,196 children were killed. At great personal risk Ai Weiwei worked to gather their names so that those children would not be forgotten. I used the translation of these children’s names as a point of departure to write a collection of poems titled ‘A Forest of Names’, some of which have appeared here, in China Heritage (see A Forest of Names — the translation of one grief to another, China Heritage, 24 April 2018). Towards the end of that project, I had the opportunity to interview Ai Weiwei in Berlin. This interview was edited into its current form from conversations that took place over several days, including a trip to Prague, those conversations also touched on his father and his father’s work.

— Ian Boyden

***

Contents

- The Editor, China Heritage, A Prelude: An Afternoon in Beijing, September 1978, China Heritage, 18 October 2018

- Ian Boyden, Introduction, and Ai Weiwei & Ian Boyden, Part I: In the Consequences of Poetry, China Heritage, 20 October 2018

- Ai Weiwei & Ian Boyden, Part II: The Prison of a Name, China Heritage, 22 October 2018

- Ai Weiwei & Ian Boyden, Part III: Exile and the Consequences of Hope, China Heritage, 24 October 2018

- Ai Weiwei & Ian Boyden, Part IV: Automatic Writing and the Spilling of Blood, China Heritage, 26 October 2018

- Ai Weiwei & Ian Boyden, Part V: The Conditions of Empathy, China Heritage, 28 October 2018

Not Yet Not Yet Complete

An Interview with Ai Weiwei

Part 2: The Prison of a Name

IB: One of the first marks we learn to leave on a piece of paper is our name. The story of your father’s name is quite unusual, and he in turn gave you a remarkable name. The story of your father changing his family name from Jiang 蒋 to Ai 艾 while he was in prison as an act of political resistance is often told. I feel something very important was born in that prison as he crossed out the lower portion of his name. You’ve been crossing it out your entire life. Did your father ever talk to you about this decision to change his name? Did he describe it to you, so you could understand your last name as a political statement?

Ai Weiwei: He mentioned he changed his name. When he was born, his parents gave him the name Jiang Haicheng 蔣海澄. But he was born a rebel; he was born to contradict his parents. For Chinese, the family name is the most important. It carries a great amount of weight and I think he never liked that aspect. I don’t think he was comfortable in his name. It was part of the conditions of his childhood, a kind of prison. His parents gave him away right after he was born then he was dragged back to his family [for more on this, see Part 1 of this interview]. He wanted to escape China and went to Paris then was pulled back because of the war with Japan. Back in China in 1932, my father didn’t like the politics of the Kuomintang and Jiang Jieshi (蔣介石, Chiang Kai-shek). So he got involved with left-wing groups in Shanghai associated with [the famous writer] Lu Xun. At that time, the Kuomintang was much softer. You could have all sorts of organisations, including leftist artist organisations. But my father immediately got arrested, sentenced, and put in jail. That was his fate.

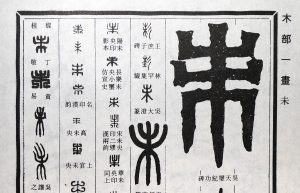

It was while he was in jail that he started to use the name Ai Qing. They say Ai 艾 is the name he created by crossing out the lower part Jiang 蔣 so it comes out as Ai. He didn’t like sharing the same family name with Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek). Qing 青 means deep blue and green together, like the color of the sea. And this Qing relates to his given name Haicheng 海澄. Hai 海 means ocean and Cheng 澄 means purified water. Ai Qing became his name.

IB: In prison, his own name escaped its own prison. Prison was like a cocoon for his name. His name experienced a form of metamorphosis.

Ai Weiwei: When he was released, nobody knew who Jiang Haicheng was, but everyone in the literary world knew the name Ai Qing. They knew this was a new poet who was so different from any other Chinese poet. He used a new language and vision. His writing was so three-dimensional. He was very liberal thinking and had great compassion for the land and its people. Nobody had ever written like that before. He was the first one to use that kind of language. To write like that made him a unique person.

IB: At what point in your life did you understand that this name was a political act?

Ai Weiwei: As a child, I didn’t understand it when he told me. To be honest, I don’t think my father would have described it as a political act. It is radical to change your family name, but it is not political. It is very radical to cross out your family name. You can dislike whomever you like, but to cut yourself off from your past, to not bear the name of your ancestors, maybe that’s the most radical thing you can do.

Ai 艾 is a type of grass used for acupuncture and healing. It is also hung on the door to prevent evil ghosts from coming in. It is a nice-smelling grass. In English it is called wormwood.

IB: How did your father choose your name?

Ai Weiwei: I am very lucky to have a unique name. I asked him what principle he used to choose his children’s names. He said there were three conditions: first, the name has to not repeat another person’s name; second, the word must not have a single meaning; third, the name must be easy to remember. Most Chinese names have some sort of auspicious meaning: good will, rich celebration, long life; or nationalistic meaning, something political or related to the army. But in my family none of the children have these kinds of names.

My father told me how he chose my name. He closed his eyes, opened the dictionary at random and pointed his finger. And the character was Wei 未. The pages fell open. I have never seen a name like mine.

IB: So your father employed a chance operation to choose your name. You must love that. Have you ever used chance operations in your writing or your art? Something along the lines of, say, John Cage and his use of the I Ching in writing music?

Ai Weiwei: My existence is already by chance. I have no further need to engage in chance operations.

IB: Your name, Weiwei 未未, could have a few potential meanings: Not yet, not yet; Unfinished, unfinished; Double negative. Maybe something to do with the future or time. Does it mean anything for you?

Ai Weiwei: Not yet, not yet. Wei 未 can also mean the future. But I never think about it. This name is just a name. It is a kind of identity, like my fingerprint.

IB: It seems there might be a semantic relationship between your first and last names. Etymologically, the ancient character ai 艾 shows a hand or a knife cutting grass, the field has been harvested, which evolved to mean ‘finished’ or ‘complete’. In Classical Chinese, wei ai means ‘not yet complete’, the grass has not yet been cut. From this perspective, your name is a state of being. Your father became ‘complete’ by crossing out the lower part of the name he was given at birth. And then he named his son Not Yet Complete, actually more philosophical than that: Not Yet Not Yet Complete.

The first recorded use of the phrase wei ai 未艾 is in the Book of Songs. The poem ‘Courtyard Torches’ 庭燎 reads in part:

Night — what is it like?

Night is not yet complete,

the courtyard torches burn like stars.

夜如何其。

夜未艾,

庭燎晣晣。

Do you think your father was thinking of this line when he selected your name?

Ai Weiwei: This must be by chance.

IB: Chance or the subconscious mind at work. This image of a torch in the courtyard as a measurement of night is really extraordinary. It is like an image of the fundamental self or one’s fundamental nature. Your name is like a koan; it causes fireworks in the mind. It reminds me of a famous koan from the Wumen Guan 無門關.

A monk asks Zhaozhou 趙州:

‘What’s the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from the west?’ 祖師因何西來.Zhaozhou answers:

‘The cypress tree in the courtyard’ 門前柏子樹.There the tree grows, it is manifesting its self, it is being what it fundamentally is. Can you tell me about how you understand the self, especially in relationship to the creative process?

Ai Weiwei: The self is a condition of existence. But is there a self before the self emerges? Or does the self only exist after the self emerges? This is the locus of the question. The self of an artist usually emerges in the process of making. The process itself creates the locus for the self to exist. The self doesn’t exist before or after. So, the self is an aspect of freedom.

IB: And no-self?

Ai Weiwei: The conditions of the self when it is in the process of emerging, relative to the existence of the fundamental self, is already a process of no-self. So the process of the emergence of the self is the process of no-self.