Citizen’s Investigation (20 March 2009-12 May 2010) was an Internet-based civil action aimed at compiling a list of the names of students who died in shoddily constructed school buildings in the Sichuan Earthquake of 12 May 2008. It was initiated by the then Beijing-based artist Ai Weiwei. In a blog post dated 20 March 2009, Weiwei issued a call for volunteers:

They say the death of the students has nothing to do with them… . They conceal the facts, and in the name of ‘stability’ they persecute, threaten and imprison the parents of these deceased children who are demanding to know the truth… . We will seek out the names of each departed child, and we will remember them… . Your actions create your world.

Over the following months, 160 volunteers gathered information in fourteen counties, 74 towns and at over 300 schools. On 12 May 2010, the second anniversary of the Sichuan devastation, Citizen’s Investigation published an online list of names and birth dates of students who had lost their lives.

***

My thanks to Ian Boyden for permission to reproduce the introduction to and selections from A Forest of Names, a work serialised in Basalt, a poetry journal produced by Eastern Oregon University in La Grande, Oregon. I am also grateful to Christopher Buckley of the New York Times, whose writing alerted me to Ian Boyden’s work.

‘A Forest of Names’ is included in Wairarapa Readings 白水札記 and it has been updated to include material from May 2018.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

24 April 2018

Remembering and Considering the Sichuan Earthquake:

- States of Emergency: the Sichuan Earthquake Ten Years On, guest edited by Christian Sorace, Made in China, vol.3, issue 1 (January-March 2018)

Fault Line

Ian Boyden

In the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, 5,196 schoolchildren were killed when their poorly-constructed schools collapsed. In an effort to conceal the corruption behind the schools’ construction, the government often brutally prevented parents and citizens alike from procuring the facts of who died, how many, and why. It wasn’t until Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, at great risk to his own safety, set about gathering the names of the children that the corruption was exposed and the names of the children were cataloged.

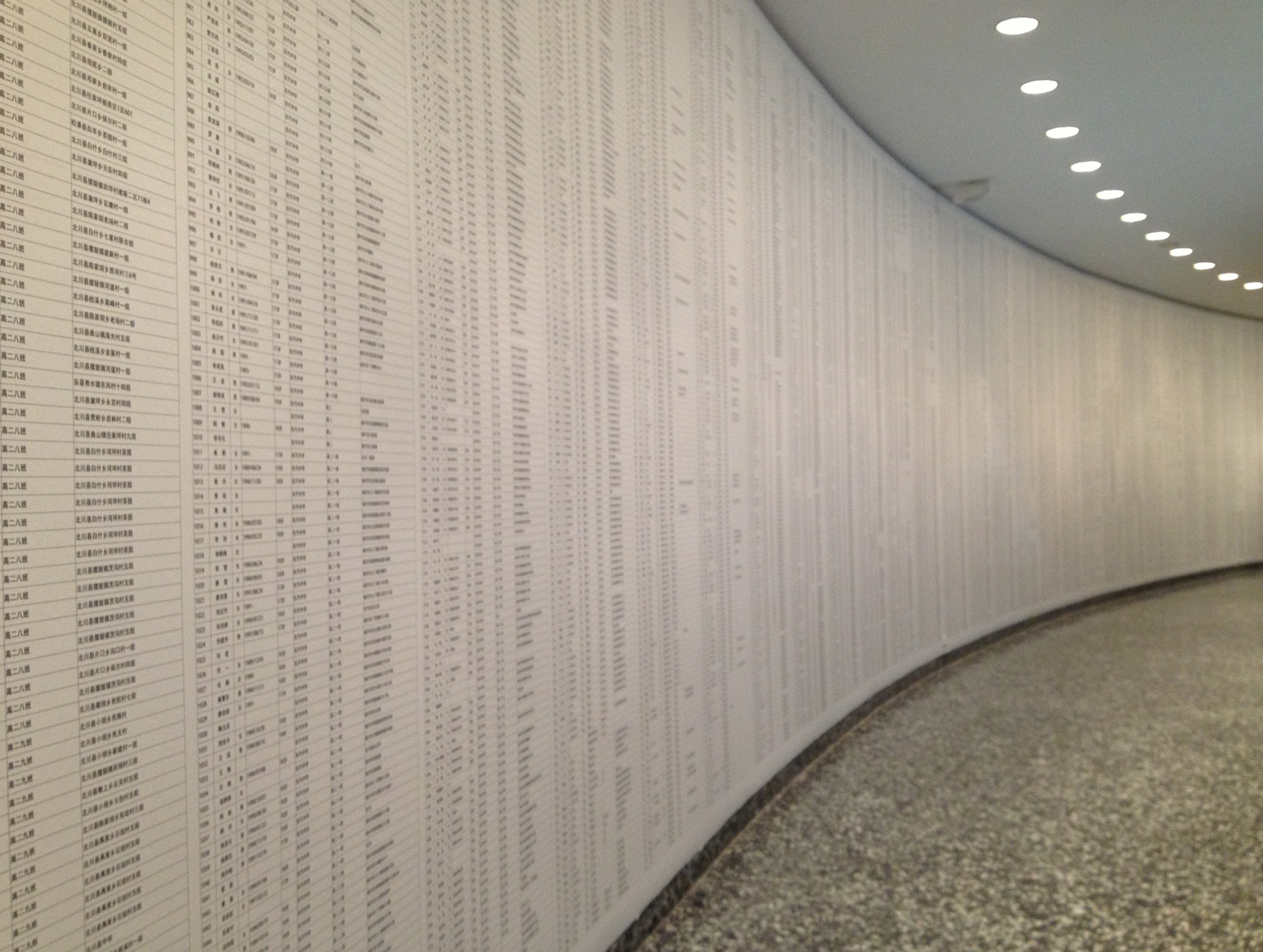

As part of an exhibition I curated of Ai Weiwei’s work related to this earthquake, I papered a wall with the names of these children, a massive work on paper consisting of twenty-one scrolls, together measuring 10.5’ tall by over 42’ long.

Hanging the scrolls took days. Each scroll had to be pasted on the back and then smoothed by hand, inch by inch, over the wall. I passed my hands over the names. The names stretched out like infinity. Each name had been a life. I read them aloud in the empty museum, ephemeral blossoms of sound. I marveled at the poetry of the names, the subtle meanings, seasonal images, literary references, philosophical challenges — each name brimmed with love, containing the hopes and dreams of the parents, as well as a challenge from the child who bore it. For me, the challenge was to give these names a kind of language so they could continue to speak.

The meditations are not formal translations, but they are rooted there. Exploring the extended meanings and the etymology of the characters provided a point of departure into a meditation whose goal is, ultimately, empathy. Chinese characters are composed of parts. Meaning arises in the relationship of these parts. Take, for example, the name 思成 Thought-Becoming (30 April). The first character 思, meaning ‘thought’ is comprised of two parts: on the top is 田 meaning ‘field’, and below is 心 meaning ‘heart’ or ‘mind’. This etymology appears in my meditation on that name:

What were you before you winged through the field above our hearts?

Returning to the etymology of the original characters is a practice in a different kind of translation: translation from one language to another certainly, as well as from one time to another, and from a character to a poetic rendering. It’s in the poetic rendering that I hoped to impart a sense of the individuality of a person to the English reader, something that is hard to achieve when reading a foreign name that does not hold a recognizable history of meaning. Holding the hopes implicit in these names in tension with the tragedy of the children’s deaths has also been a translation of one grief to another: perhaps this is the most accurate translation of all.

Chinese characters typically have a multiplicity of meanings, which are clarified by context. But with a name, there is little or no context, and I have no way of reaching out to the parents to find out what their intentions were. This leaves me alone with raw material and my own empathy.

Ai Weiwei sees our world as profoundly lacking in compassion, that were our decisions driven by compassion, we would avoid or at least alleviate suffering. A primary driver of compassion is empathy. But empathy cannot be imposed, rather it must arise from within, an element that binds us to each other. For me, the empathetic demand is the great gift of his work to our culture and to myself.

Ai Weiwei uses Twitter as a primary means of communication. From 2009 to 2017, he tweeted the names of these children every day on their birthday, continuously calling for those responsible for the deaths be held accountable. The tweets simply read: ‘Today is the birthday of [x] number of students who were killed, they are:’ and then the list of names, followed by the hashtag #512Birthday. Each morning for one year, I read the names, translated a few of them, and then wrote a meditative response. My daily responses fit the 140 character count of the Twitter platform. And then I tweeted it to Ai Weiwei and the rest of the world. In the year that followed, I returned to each poem on its given day, revising and expanding on themes I had discovered in the process.

What follows are selections of these poems presented in monthly installments.

— from Basalt, 13 April 2018

***

A Forest of Names — February

Ian Boyden

FEBRUARY 1

明靜

Motionless Clarity

There, where moonlight spills

across a handful of ash.

FEBRUARY 2

霽

Clearing Sky

He stood on his head,

and to his astonishment

watched the clouds ripening

like fields of grain.

FEBRUARY 8

小森

Small Forest

Once finished with the trunk,

the brush dances side to side.An infinity of black

from the heart

of a burning pine.

FEBRUARY 9

恆光

Fixed Radiance

A carving of light,

a hewn moon,

a heart suspended

between two shores.

FEBRUARY 10

苗苗

Sprout Sprout

And from the same quarry

that lined the mausoleum of a tyrant,

the blocks of marble were carved

into a field of white grass.

FEBRUARY 11

林萌

Forest’s Beginning

Once lost to centuries of ice,

the seeds split stones and called outtoward the sun and moon,

and so laced a tapestry

of impenetrable shadow.

FEBRUARY 12

沚君

Sandbar Lord

The edges of his heart,

written by the footprints of plovers,

anchored by love,

washed by rain.

FEBRUARY 14

婧涵

Modest Implication

Ink spilled from where she split the world in two,

wrote its fluid song whispering

of days filled with love.

FEBRUARY 15

蕾

Unopened Flower

Your whole life unfolds in the silence after lightning’s flash.

What sprouts from the thunder?

FEBRUARY 18

書晟

Book of Solar Luminosity

Once bound, the book

could never be held,

could never be read,what it offered

was the light

of its own transformation.

FEBRUARY 20

代言

On Behalf of Words

No matter how carefully they held the calipers,

the birds always escaped their names.

But the child,

the child slowly grew into his.Until one day,

he held calipers to his own heart,

only to have it become a bird,and it sang:

no words,

no words.

FEBRUARY 23

瀚墨

Vast Ink

At sunrise,

the white feather fell

from an empty sky.Now blackened

with a century of burning,

it erases the stars.

FEBRUARY 24

杰

Outstanding

Every time his name was uttered,

a tree burst into flame.

FEBRUARY 25

文淵

Literary Abyss

Words bubble forth from the deep.

Which ones change our hearts?

Which ones collapse a building?

FEBRUARY 28

紫蘭

Purple Orchid

The path blocked

by a curtain of flowers,

each flower a closed door

twined shut

in the figure eight of infinity.

FEBRUARY 29

城霖

City of Endless Rain

Earth becoming

walls, stone by brick,

to shelter us from forests of rain,

and centuries of forests devour the city,

its walls, leaf by root,

becoming earth.

***

Further Reading:

- Ai Weiwei, Never Sorry, 2012

- Ai Weiwei, 5.12 Citizen’s Investigation, Aiweiwei.com

- Geremie R. Barmé, A View on Ai Weiwei’s Exit, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 26 (June 2011)

- Christian Sorace, In Rehab with Ai Weiwei, The China Story Journal, 14 October 2015

- Christian Sorace, Shaken Authority: China’s Communist Party and the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, Cornell University Press, 2017

- Robin Pogrebin, Ai Weiwei’s Little Blue Book on the Refugee Crisis, New York Times, 23 April 2018

- Daxel, Fragile as an Urn: An Interview with Ian Boyden, 6 May 2018

***

Q.: You have said that your early blogs were often funny. Yet most of your more recent artistic expression seems fairly serious. How do you explain that?

Ai Weiwei: I probably used up all my humor. I have no humor anymore.

Q.: Given the immensity of the refugee crisis, why even try to make an impact? Do you ever get frustrated by a sense of futility?

Ai Weiwei: How do you prove you’re living at this time? We are given one time to live. You’re a passenger passing through, you leave some traces. In China we say, ‘When birds pass over the sky…’ I’m just one of the birds who made some sounds. Wind will blow them away.

— from Robin Pogrebin, Ai Weiwei’s Little Blue Book on the Refugee Crisis,

New York Times, 23 April 2018