Drop Your Pants!

The Party Wants to

Patriotise You All Over Again

(Part II)

‘The Party Empire’ is the second part of Drop Your Pants!, our overview of the Patriotic Education Campaign launched by China’s Communist Party on the last day of July 2018, and the latest in our series of Lessons in New Sinology. In it we provide a simple guide to the history of how, at different times and under different leaders, political parties and state administrations in China have coalesced to create what is known as the ‘party-state system’, dǎngguó tǐzhì 黨國體制. According to this system, to love one’s country, that is to be a patriot, it is also mandatory to love the ruling party.

An expression first used some ninety years ago, and one suffused with an overwhelming odeur for nearly half a century, ‘party-state’ was revived as a positive concept by pro-Party, hyper-patriotic thinkers on the Mainland in the new millennium. These supporters of ‘Statism’ 國家主義 advocated on behalf of a stronger party-state; for them dǎngguó 黨國 was no mere description of Chinese reality, it was an aspiration.

Recently, in the welter of Chairman Xi Jinping’s irresistible rise, international observers and academics have had an epiphany of their own, and the expression ‘party-state’ is now frequently employed with something akin to a smug, all-knowing flourish.

***

‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’ is a five-part introduction to the Patriotic Education Campaign launched by Party Central on the last day of July 2018:

- Part I — Ruling The Rivers & Mountains — reviewed the Thought Reform Movement of the early 1950s, which included the Party’s inaugural patriotic re-education putsch, and noted its connection to the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942-1943, which we discussed in Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous. We believe that a basic familiarity with those earlier movements is helpful in understanding not only the 2018 Patriotic Offensive, but also the Communist Party’s ‘correctional re-education’ 矯正教育 policies in Xinjiang and Tibet;

- Part II — The Party Empire — below, provides a short account of how, under various regimes and leaders, party and state have been melded and promoted in twentieth-century and early twenty-first century China. This contentious history is useful in appreciating that country’s politicised patriotism;

- Part III — Homo Xinensis — considers the history of the comrade-but-not-citizen and the hyper-patriots imbued with Core Socialist Values that are nurtured and encouraged by the party-state under Xi Jinping;

- Part IV — Homo Xinensis Ascendant — outlines the desiderata for Homo Xinensis today, and for the future. By way of contrast we also quote from Alexander Zinoviev’s Homo Sovieticus, the Doppelgänger of the New Person of Xi Jinping’s New Epoch; and,

- Part V — Homo Xinensis Militant — this final essay in ‘Drop Your Pants!’ discusses Red DNA 紅色基因, Peaceful DNA 和平基因 and how traditions of warfare and the lyrical militancy of revolution commingle to create a romanticised warrior ethos.

This series also takes up some of the themes in the 24 July 2018 public appeal by Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun’s 許章潤, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待 (China Heritage, 1 August 2018).

***

Mencius famously remarked:

The wise know that to enlighten others requires clarity [oneself]; today, those befuddled by the dark presume to shed light. 賢者以其昭昭,使人昭昭;今以其昏昏,使人昭昭。——《孟子 · 盡心下》

One can only hope that readers both of this and of our other Lessons in New Sinology will find more light than darkness here.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

17 August 2018

***

Other Lessons in New Sinology:

- The Editor, Mendacious, Hyperbolic & Fatuous — an ill wind from People’s Daily, China Heritage, 10 July 2018

- The Editor and Lee Yee 李怡, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018

- The Editor and Others, It’s Time to Talk About Evening Talks at Yanshan 燕山夜話, China Heritage, 20 July 2018

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad 我們當下的恐懼與期待, trans. with notes by Geremie R. Barmé, China Heritage, 1 August 2018

One Nation Under the Party

黨國

1920s

Since the 2008 Beijing Olympics a political term dating from the 1920s has enjoyed renewed popularity both in China and internationally. ‘Party-State’ 黨國 is a shorthand for ‘One Party Rules the Country’ 以黨治國, that is the domination of the state by a single political party.

The revolutionary Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙, 1866-1925), the celebrated Father of the Chinese Republic whose portrait is installed on Tiananmen Square in Beijing twice annually to mark the 1st of May International Labor Day and 1st of October National Day, first championed the concept of the ‘party-state’ in the 1920s.

***

Frustrated by the schisms tormenting China following the founding of the Republic of China in January 1912, and inspired by the successes of one-party rule in the newly established Soviet Union, Sun proposed emulating the Soviets and embracing the Communist Party (founded in 1921) 聯俄容共. He formulated a three-stage political timeline: following Military Rule 軍政, aimed at the enforced unification in the face of civil strife and warlord contestation, China was entering an era of Political Tutelage 訓政. Although the long-term aim was a transition to Constitutional Politics 憲政 — that is the rule of law and democracy — in the interim, and for the sake of the unity, prosperity and strength of the nation it was necessary for one party under a strong leader to hold the reins of power.

Sun’s summed up his ‘Party-over-State’ strategy in six points:

- Everyone in the country must support the ideology of the party 全國人都遵守本黨的主義;

- The premier has absolutely final say over all decisions of the central government 總理對中央執行委員會之決議有最後決定之權;

- The country is ruled by the Party and apart from a necessary number of technical officials all members of the government must be Party members 吾黨以黨治國,黨、政府下之官吏,除政府需要專門技術人才,可取用非黨員外,其餘概須入黨;

- The Party is above the country 將黨放在國上;

- There must be only one Party, all others must be eliminated in favour of the Revolutionary Nationals Party which then will rule the Republic of China 必將反對黨完全消滅,使全國的人都化為革命黨,然後始有中華民國; and,

- A national flag embodying emblems of the Nationalist Party 青天白日滿地紅.

***

A Four-character Classic

《國民黨四字經》

Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀

1927

In commenting on the irrepressible factionalism of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, Mao Zedong quoted lines from a famous doggerel poem by Chen Duxiu (陳獨秀, 1879-1942), who led the Communist Party from 1921 to 1927. Chen wrote his Four-character Classic for the Nationalist Party 國民黨四字經 in 1927, following the bloody split between the Nationalist and Communist parties that led to the Nationalists building their party-state:

One Party Without Others?

Imperial thinking;

A Party Without Factions,

That’ll be the Day!

The Party Reigns Supreme,

Political Folderol;

Party Indoctrination,

Poison of the Past.

The Three People’s Principles,

Stuff and Nonsense;

A Constitution with Five Yuan,

An Incoherent Grabbag.

Fundamentals of Nation Building,

Bureaucratic Balderdash;

Purge the Party of Communists,

Bid Farewell to the Revolution.

The Period of Military Rule —

Warlords Come Out to Play;

The Period of Tutelage —

Payday for the Bureaucracy;

Constitutional Government —

Distant and Unobtainable.

Loyal Party Members,

Only After Hard Currency;

Just Recite the Final Testament:

A-mi-tuo-fo! A-mi-tuo-fo!

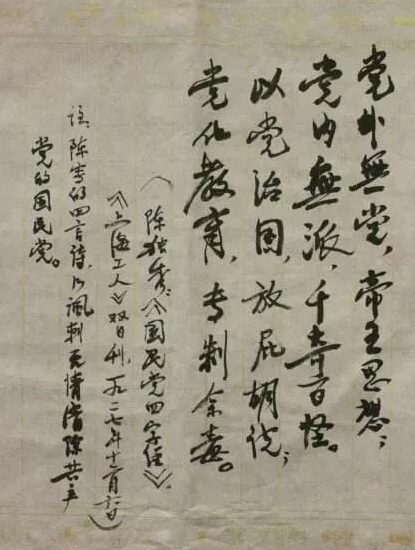

黨外無黨,

帝王思想;

黨內無派,

千奇百怪。

以黨治國,

放屁胡說;

黨化教育,

專制余毒。

三民主義,

胡說道地;

五權憲法,

夾七夾八。

建國大綱,

官樣文章;

清黨反共,

革命送終。

軍政時期,

軍閥得意;

訓政時期,

官僚運氣;

憲政時期,

遙遙無期。

忠誠黨員,

只要洋錢;

恭讀遺囑,

阿彌陀佛。

Key:

- One Party Without Others 黨外無黨: following the bloody purge of their Communist Party fellows, the Revolutionary Nationalist Party, later known as the Nationalist Party or Kuomintang, was the sole political organisation in power;

- Three People’s Principles 三民主義: Nationalism, Democracy and Welfare, according to Sun Yat-sen’s particular interpretation;

- A Constitution with Five Yuan 五院: the Nationalist government administration consisted of five branches, the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Control Yuan and Examination Yuan;

- Fundamentals of National Reconstruction 建國大綱: an aspirational document composed by Sun Yat-sen and adopted in 1924 which outlined the functions of the government and the stages of the country’s political development;

- Purge the Party of Communists 清黨反共: a massacre of Communists that started in Shanghai on 12 April 1927;

- The lines 訓政時期,官僚運氣;憲政時期,遙遙無期 (Under the party’s political tutelage, the bureaucrats strike it rich;/Constitutional government, that’s for a far distant future) appear as grimly humorous today as they were over eighty years ago. In early 2013, hopes for political reform under Xi Jinping in the name of ‘constitutionalism’ 憲政 were dashed (for more on this, see below);

- Final Testament 遺囑: Sun Yat-sen’s Will 總理遺囑, transcribed in February 1925 shortly before Sun died, offers a retrospective of his revolutionary struggle along with an exhortation to the people of China for the future; and,

- A-mi-tuo-fo 阿彌陀佛 (Amitābha अमिताभ in Sanskrit): a prayer-salutation to the Buddha of Longevity. Equivalent to ‘Heaven Help Us!’

— trans. with notes by G.R. Barmé

***

Constitutional Interlude, I

1931 & 1936

A Provisional Constitution 約法 of the Republic of China was adopted by the National People’s Convention 國民會議 on 12 May 1931. It included Sun Yat-sen’s principle of ‘political tutelage’ 訓政 which formalised the party-state system, also known as 黨國一體, and endowed the Nationalist Party government with dictatorial authority. This Constitution remained in effect until 1936.

A new draft constitution was announced on 5 May 1936. It vested executive power in the President of the Republic but failed to allow for substantial legislative oversight over or checks on that power. A National Convention was to be convened on 12 November 1936 so the constitution could be adopted formally. The outbreak of hostilities with Japan on 7 July 1936 delayed the convocation indefinitely.

The Provisional Constitution was China’s most substantial national law after the promulgation in August 1908 of the Qing dynasty’s Outline Constitution by Imperial Order 欽定憲法大綱. That document, which was modeled on the Japanese Meiji Constitution, promised to transform a dynastic autocracy into a constitutional monarchy.

One Party, One Leader, One Ideology, One Army

一個政黨、一個領袖、一個主義、一個軍隊

1938-1949

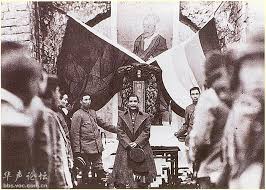

Under the rule of the Nationalist Party on the mainland from 1928, following a period of forced military unification, and the establishment of a central government in Nanjing, until victory of the Communist Party in the Civil War twenty years later, China was effectively a party-state. The Nationalist government celebrated the fact. It merged its party flag with that of the Republic of China and even the national anthem extolled the ruling party. In early 1938, with Chiang Kai-shek’s assertion of his wartime authoritarian leadership, summed up as 黨國至上, and drawing inspiration from Hitler’s Germany, the Nationalist propaganda machine called on the nation to support:

One Party, One Leader, One Ideology, One Army

一個政黨、一個領袖、一個主義、一個軍隊

At the Communist guerrilla base in Yan’an, northwest China, far from the Nationalist’s wartime capital of Chongqing in Sichuan province, Mao also declared himself in favour of the ruling political party maintaining overlordship of the state, as well as the pivotal role of the leader. In 1942, as the Yan’an Rectification Movement cemented his ideological domination, Mao promoted what was called the monolithic leadership 黨的一元化領導 of the Communist Party(see here). On both sides of the political divide at the time strong leadership was regarded as being crucial to the war effort. The same also held true for Wang Jingwei (汪精衛, 1883-1944), head of the ‘reorganised national government’ in the former Nationalist capital of Nanjing which collaborated with the occupying Japanese army (see Nanking’s ‘Government of ‘Traitors’, 1940-1945, China Heritage, 15 May 2018.)

In many ways, the political monolith advocated both by the Nationalists and the Communists evoked the concept of ‘Grand Unity’ 大一統, an ancient expression used to describe an ideal world for the power-holders, one in which political power, economic management, cultural activity and the life of the mind were all brought under their sway. The Grand Unity had been espoused from the time of the Warring Staes period. It was the ideal of successive dynasties from the time of Ying Zheng (嬴政, 259-210BCE), First Emperor of Qin 秦始皇 (r. 220-210BCE).

Sources:

- 姜福禎, 民主發生的路徑——讀許良英《民主的歷史》, Independent Chinese Pen Center 獨立中文筆會, 17 March 2016

- 盛禹九, 漫談「黨國體制」 ──答一位年輕朋友, 環球實報, 4 March 2017

Constitutional Interlude, II

1946

From 10 to 30 January 1946, with the collaboration of the Communist Party and representatives from other political parties, the Republican government convened a Political Consultative Congress. The congress called for substantive changes to the Draft Constitution of 1935, including the creation of a democratic legislature and circumscribing the powers of the president.

In December 1946, a National Assembly comprising representatives of all political parties, again including the Communists, was duly convened. It ratified a new constitution which was promulgated on 25 December 1947. This document effectively ended the period of Political Tutelage that had lasted for two decades and theoretically ushered in the third stage of China’s modern politial evolution: Constitutional Rule 憲政, something that was supposed to assure the democratic rights and basis freedoms of Chinese citizens.

During this period, the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, in particular Liu Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai, who were in direct, and escalating, competition both ideologically and militarily with the Nationalist Party made numerous speeches and public statements, and published many editorials in the press, that affirmed Communist support for democracy and human rights (for a collection of this material published, and immediately banned, in 1999, see Xiao Shu, ed., Promises to History 歷史的先聲——半個世紀前的莊嚴承諾). As part of a United Front strategy devised and constantly refined over the years, these numerous high-profile undertakings had a significant impact in swaying the opinion of many members of the intelligentsia, students as well as a broad spectrum of patriots to support the Communist cause. The realities of Party rule in Yan’an, in particular during and after the 1942-1943 Rectification Campaign, were little known.

Following the outbreak of civil war in mid 1946, the Communists withdrew from all constitutional arrangements, although other political parties would continue to work to end the conflict and to re-establish a broad based unity democratic government. To that end these parties continued to collaborate with the Nationalists, while engaging in ongoing negotiations with the Communists.

On 10 May 1948, the National Assembly, which was dominated by Nationalist President Chiang Kai-shek and his party, enacted Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Mobilisation for the Suppression of Communist Rebellion 動員戡亂時期臨時條款. These granted the president unfettered powers to deal with the ‘immediate danger’ of what were called the ‘Communist Bandits’ 共匪 for a period of three years. Following the retreat of Chiang’s government to Taiwan, these provisions became the legal basis on which the Nationalist Party imposed four decades of martial law on the island. The ‘temporary provisions’ were terminated on 1 May 1991.

Time Starts Now

時間開始了

1949

Shortly after the inauguration of the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949, the Communist literary critic and poet Hu Feng (胡風, 1902-1985) wrote a lengthy paean to the new state, and its leader, Mao Zedong. Entitled ‘Time Starts Now’, it read in part:

The great circular auditorium

Is like a globe floating in the universe

All around it

Countless red flags

Dance and flutter in joy

It is as though they are singing

Dancing redder still and more brightly

Like jumping flames

They light up

The 30,000 fighting hearts

Near them

They have been washed by the storm

Blown by the wild winds

Fluttering with joy

Redder ever still.

圓形的大會場

象一個浮在大宇宙中間的地球

整列在那邊緣上的

濕透了的無數紅旗

飄舞得更響更歡

好象在歌唱

飄舞得更紅更鮮

好象是跳躍著的火焰

被它們照臨著的

三萬顆戰鬥的心

被暴雨洗過

被狂風吹著

也更響更歡

也更紅更鮮

— 胡風, 《時間開了》

人民日報, 20 November 1949

***

Hu Feng was hardly unique in thinking that time itself was rebooted by the start of a new political era. In traditional terms, this was known as ‘regime change’ 改朝換代 or ‘establishing a beginning’ 建元, a term used for each new reign during a dynasty. The latter expression is not that dissimilar from the expression ‘new era’ or ‘new epoch’ 新時期 under the Communists. At the time, Deng’s political rebirth and rise to power in 1978 was hailed as a ‘new era’, just as, from the Nineteenth Party Congress in late 2017, Xi Jinping’s term-less tenure (which has been back-dated to October 2012) was also acclaimed as a ‘new era’.

When the victorious Manchu-Qing army replaced the Ming dynasty and moved its court from Shengjing 盛京 (modern-day Shenyang) beyond the Great Wall to the Ming capital Beijing in 1644, the official historians recorded that:

With a reverent announcement to Heaven and Earth, and by making a formal declaration at the Ancestral Temple and Altar of State, the Great Qing dynasty is now established here [the Latter Jin dynasty of the Manchus had been renamed Great Qing in 1635] and the Tripod Cauldron [of sacred rulership] installed in Yanjing. The first reign titled Shunzhi [the emperor Shizu, whose name was Aisin Gioro Fulin] inaugurates a glorious enterprise that has been achieved with immense difficulty. This augurs Reform, a process blessed by Renewal. 祗告天地宗廟社稷,定鼎燕京,仍建有天下之號曰大清,紀元順治。緬維峻命不易,創業尤艱。況當改革之初,爰沛維新之澤。

— Draft History of the Qing Dynasty

Chronicles IV: Emperor Shizu I

《清史稿》本紀四 世祖本紀一

On 15 February 1912, three days after the last ruler of the Qing dynasty formally abdicated, Sun Yat-sen, the newly appointed temporary president of the Republic of China, performed a ceremony at Xiaoling 孝陵, the tomb of Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋, founder of the Ming dynasty (r. 1368-1398). Using a modernised liturgy sacrifices were made, the large delegation of anti-dynastic revolutionaries paid obeisance at the tomb and prayers were intoned. These including a proclamation addressed to the long-dead Ming ruler read out by Sun Yat-sen. He informed his racial ancestor that, after years under the yoke of the foreign Tartar invaders, ‘Light is Restored’ 光復 to China (for details of Sun’s proclamation, see here).

In 1929, two decades before Hu Feng composed his ecstatic paean to New China, the original socialist state of the Soviet Union ushered in what was hailed at the time as a ‘cultural revolution’. This was a revolution within a revolution, one that would see the complete proletarianisation of culture, a process aimed to ‘propel the country … to a postbourgeois culture system’, and one which would instill in the populace ‘a truly socialist consciousness and way of life.’

Hu Feng’s ‘Time Starts Now’ recalled, intentionally or not, a declaration that Joseph Stalin made at the advent of the Soviet Union’s 1929 cultural revolution. Stalin had said that year was nothing less than a ‘grand fracture’ or ‘great breakthrough’ большой перелом, one that represented ‘a total break in time’. (See Katerina Clark, Moscow, the Fourth Rome, 2011, p.44.)

In China, the split in time, between the old and the new, was as stark as it would be relentless. The pre-1949 Old China 舊中國, also known as the Old Society 舊社會, was one in which the peoples of China – and this was the territory of the former Manchu-led Qing dynasty, later claimed by the Republic of China (1912-1949) – had been crushed under the oppressive weight of what Mao Zedong called the ‘three great mountains’ 三座大山 of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucratic-capitalism.

Time started anew with the birth of New China 新中國, created as a result of the 1949 liberation when the People of China had stood up. It brought to an end what would later be called ‘a century of humiliation’ starting with the first Opium War in 1840, a hundred years during which, due to the desuetude of Manchu dynastic rule, ‘China’ had fallen prey to the incursions of imperialism, being reduced over time to the status of a semi-feudal, semi-colonial society. As the propagandists would tell it, certainly, the 1911 Xinhai Revolution had brought an end to two millennia of dynastic feudal rule, but China’s benighted state did not thereby fundamentally change. The May Fourth movement of 1919 marked the beginning of a new democracy revolution, however, the truly epoch-making event was the founding in 1921 of the Chinese Communist Party. Following twenty-eight years of struggle, and under the leadership of Mao Zedong reinforced by the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942, the Party-led new democratic revolution finally celebrated its victory with the establishment on 1 October 1949 of New China.

The historians of New China, influenced profoundly by Republican-era debates and the historiographical timescape of the Soviet Union that calibrated the stages of social change and revolution, now set about creating a periodisation and logic for the onward flow of Chinese history itself. Time started anew; for a time it was thought that the Chinese people were liberated from the past.

— adapted from G.R. Barmé

Telling Chinese Stories

1 May 2012

***

Year Zero

Only months after declaring that ‘Time Starts Now’, Hu Feng would be caught up in a horology that predated the 1st of October 1949.

Although the historical point of origin for China’s Communist Party was 1 July 1921, time really only began with the 1942 Yan’an Rectification Campaign, the subject of a previous Lesson in New Sinology. In many ways, 1942 was Year Zero both for Chinese political life under the Communists and its cultural life. A series of remarks Mao made regarding the arts during the Rectification — published as ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art’ 延安文藝座談會上的講話 — was, and remains, the canonical text for official culture in the People’s Republic.

The Yan’an Rectification itself and the ‘investigation of cadres’ 審幹 (a vicious process inspired by Stalin’s purges which involved identifying and eliminating ‘Trotskyites, Japanese spies and Nationalist Agents’ — at the time, Hu Qiaomu declared that ‘there are numerous enemy agents [in Yan’an], you can find them everywhere’ 特務如麻,到處皆有) that was part of the rectification, created a political arrhythmia that has been the measure official Chinese life ever since. It is a syncopation of factional infighting, paranoia, the targeting of enemies and purges that correlates with the Communist Party’s own calendar of ritualised meetings, congresses, decisions and campaigns.

In Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, we outlined how, following the Communist victory in 1949, the Party launched a Thought Reform Movement aimed at resetting the political consciousness of the nation. People were to learn that henceforth in their hearts and minds they should ensure that their patriotic sentiments along with their personal aspirations were at one with the (malleable) unitary vision and priorities of the Communist Party.

As the Thought Reform Movement took hold in the nation’s universities, the civilian population was also being re-educated in a new style of pro-Party patriotism. In the process, a new rectification of the Communists themselves was lauched to attack waste, bureaucracy and graft. Starting in early 1951, the ‘Three Anti’ and ‘Five Anti’ movements also focussed on the former Nationalist government administration, and those who had worked for it. Many were subjected to investigation, criticism and re-education so they could learn to serve what would be known as the Proletarian Dictatorship. Numerous former Nationalist employees and members of the army were subjected to repeated rounds of interrogation, forced isolation and reform until after Mao’s death.

***

Hu Feng himself soon fell foul of the ‘New China Time’ or ‘Beijing Time’ that he had only recently celebrated. Regarded from the the days of the Yan’an Rectification as an ideological and factional enemy by Maoist cultural figures (including Chen Boda and Hu Qiaomu, Yan’an-era ideologues mentioned in Drop Your Pants! Part I, as well as the later ‘Cultural Tsar’ 文化沙皇 Zhou Yang 周揚), as well as for having the temerity to disagree about cultural and literary policy with Mao himself, Hu was initially targeted for denunciation as early as March 1950 but, since his persecutors were busy with other enemies, his fall was delayed. His main cultural crime was that he argued for the subjective nature of literature and the individual creativity of the writer. He was also critical of the Maoist cultural policy that overly emphasised Chinese ‘national forms’ over more modernising cultural trends. Hardly a liberal or independently minded, in fact there was as much of Stalin in his thinking as Mao; nonetheless, Hu did not support the idea that all cultural expression had to have an obvious political motive or purpose.

What in many ways was an obscure spat within the Communist establishment on cultural theory was made public so as to ‘instruct’ 教育, that is intimidate, the broader population by the sheer scale and ferocity of the criticism of Hu and his ideas. This, too, would be a practical lesson in party-state-style ‘Patriotic Education’: in regular mandated study sessions throughout the country normal people would learn, with each successive mass political campaign, that to love the Counrty 國家 you had to know how to hate the Enemies of the Party, no matter who they were. For a time, Hu Feng and his associates, real and imagined, were the focus of national hate.

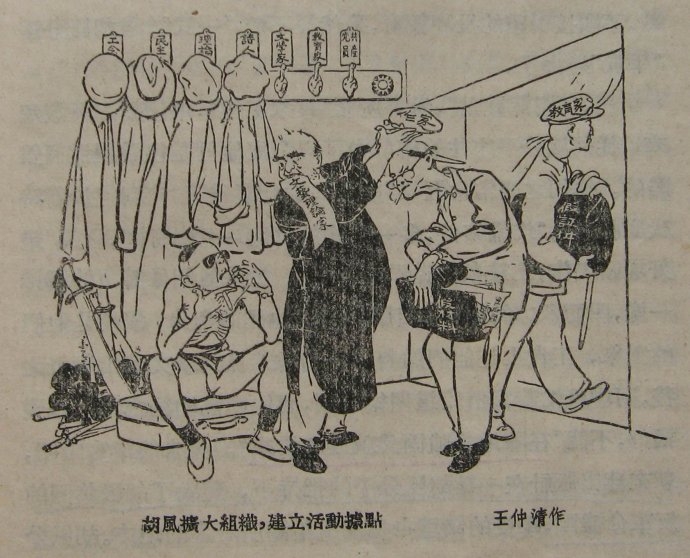

After years attacking the writer’s culturally unacceptable views finally, in early 1955, the Party propaganda apparatus claimed that it had uncovered a vast conspiracy. The ‘Hu Feng Anti-Party Clique’ 胡風反黨集團 was identified and publicly denounced at great length and in considerable detail, including by some of Hu’s closest associates and friends, and yet again with the help of the propaganda chief Hu Qiaomu.

The writer was detained as a dangerous threat to the country and, during the nationwide witch-hunt that ensued, over two thousand people were identified as members of his clique: ninety two were arrested; sixty two men and women were subjected to isolated interrogation; and, another seventy three were suspended from their jobs so they could ‘dwell on their sins’.

In 1956, seventy eight people were named as ‘Hu Feng Co-Consipators’, thirty of whom were Party members; twenty-three were investigated as core activists. After ten years in prison, Hu was finally formally sentenced to fourteen years more gaol. This was converted to a life sentence in the Cultural Revolution. Hu, along with the other members of this make-believe conspiracy were exonerated in 1980, twenty-four years after having been denounced. However, the official attacks on Hu Feng’s literary views were never been overturned and Mao’s ‘Yan’an Talks’ which declare that all cultural activity should serve the Party remain sacrosanct to this day. For his part, Hu Qiaomu would express a measure of regret, although he indicated that anything less than unwavering support for Mao’s implacable attack on Hu Feng would have compromised his own career.

Constitutional Interlude, III

1949 & 1954

In January 1946, a Political Consultative Congress agreed to by the Nationalist government of the Republic of China and the leaders of the Communist Party, convened in Chongqing. It included representatives of China’s other major political parties (see Constitutional Interlude II above). In November 1948, at the height of the ensuing civil war between the Nationalist and Communist armies, and as part of the on-going pursuit of their United Front strategy, the Communists prepared for the establishment of a Political Consultative Congress of their own, one that included representatives of the other political parties, leading ‘democratic personages’ 民主人士, ethnic groups and Overseas Chinese delegates.

The first preparatory meeting of the congress was convened in Beiping (Beijing) on 15 June 1949. Participants were given to understand that following a Communist victory, a ‘government of unity’ 聯合政府 with representatives of all political parties and interest groups would replace the Nationalist party-state.

On 17 September 1949, at the second preparatory meeting of the Congress, the meeting adopted the name ‘Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference’ 中國人民政治協商會議. At the inaugural meeting of this new body on 21 September, Mao Zedong famously proclaimed:

The Chinese People Have Stood Up!

中國人民站起來了!

The phantasmagoria of China’s ‘multi-party consultative system’ of government was thereby born. (Or, as a famous comic line puts it: 中國人民站起來了中國人打趴下了: ‘The Chinese People [ie, the Communist Party] has stood up, but the Chinese have been knocked down.’)

***

In September 1954, the newly organised National People’s Congress 中國人民代表大會 — a ‘parliament’ with representatives pre-selected by the Party that subsumed the formalistic legislative functions of the post-1949 People’s Political Consultative Conference — was convened to adopt the first constitution of the People’s Republic. That document, written by Mao and his advisers, was based on the constitution of the Soviet Union, China’s party-state mentor since the 1920s. Among other things, it celebrated the realization of ‘democratic socialism’ and a ‘socialist legal system’ and claimed that the ties friendship between the Chinese People’s Republic and the Soviet Union was ‘unbreakable’ 牢不可破. On that occasion, Mao Zedong unequivocally declared that:

The Chinese Communist Party

Is the Core of Our Enterprise

領導我們事業的核心力量是中國共產黨。

Two years later, on the occasion of the ninetieeth anniverary of Sun Yat-sen’s birth in December 1956, Mao extolled the Republican revolutionary saying that, despite his flaws and limitations, Sun ‘stood on the crest of the tides of history’, a history of democracy and socialism in China that the Chinese Communist Party would fulfill.

And, six months after that, in a letter to Party Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, Chu Anping, a famous ‘democratic personage’, one of the most influential editors and journalists during the last years of Nationalist rule, would speak about his reservations concerning what was, in effect, a new party-state, one that betrayed the previous undertakings of the Communist Party itself.

The Party Empire

黨天下

1957

The Hundred Flowers Campaign from 1956 to 1957 was promoted by the Communists as another Rectification, a ‘righting of the winds’, akin to that of 1942-1943. It was ostensibly aimed at encouraging people to air the criticisms and grievances that had built up during the first years of Party rule (and also as a result of the Communists numerous broken political promises), but only to do so in a ‘constructive manner’. People were told they should ‘help the party rectify itself’ 幫助黨整風. Here we introduce two men who spoke out: first, the journalist and editor Chu Anping (儲安平, 1909-1966) and, further down, the playwright and film-maker Wu Zuguang (吳祖光, 1917-2003).

In the last years of the Nationalist government, Chu had edited The Observer 觀察, a nationally popular political magazine published fortnightly. Eventually, Nationalist Party censors forced the magazine’s closure and, for a time, Chu, despite being all too aware of the limits the Communists would place on freedom of speech, entertained the idea of reviving his publication after 1949. He was encourage in this by none other than Hu Qiaomu, who was now the Communist propaganda chief and an avowed ‘friend of intellectuals’ (in Part I, we saw him play a similar role in enlisting his Tsinghua University schoolmate Qian Zhongshu to contribute to the English translation of Mao Zedong’s works).

At Hu’s suggestion, Chu relocated to Beijing from his base in Shanghai and The New Observer 新觀察 was founded in late 1949. Only allowed to publish anodyne, pro-Party pap, however, the magazine soon folded due to lack of readership. After some years working in the reorganised Party-dominated publishing industry, in April 1957 Chu was assigned a prestigious job as the editor-in-chief of Guangming Daily. During the early years of the People’s Republic he was also accorded other honours for he was regarded as being a significant ‘democratic personage’, one of a group of ‘democratic individualists’ 民主個人主義者 that Mao had variously mocked and manipulated in the lead up to the Communists taking power.

Initially reluctant to participate in the Hundred Flowers, Chu finally gave in to requests from colleagues and Communist leaders to make a statement.

***

***

Some Advice for Chairman Mao and

Premier Zhou Enlai

向毛主席和周總理提些意見

Chu Anping 储安平

The crux of the problem lies with what I call ‘The Party Empire’. In my opinion the Party’s control of the state does not give it the right to treat the nation as its personal property. Everyone supports the Party, but no one has forgotten that it is the Master of the Nation. The main concern of a political party that takes power should be the realisaiton of its ideals and implementation of its policies. Certainly, a party needs to remain strong so that it can do this and maintain stability; it need control over some crucial sectors of the state mechanism. This is quite natural. However, to put a Party boss in every unit and organization throughout the nation, in every bureau and group, and to make everything, no matter how large or small, contingent on the reaction of the Party man, to force people to rely on the Party man’s nod of approval to do anything, is surely somewhat extreme, isn’t it?

這個問題的關鍵究竟何在?據我看來,關鍵在「黨天下」的這個思想問題上。我認為黨領導國家並不等於這個國家即為黨所有;大家擁護黨,但並沒忘了自己也還是國家的主人。政黨取得政權的主要目的是實現他的理想,推行他的政策。為了保證政策的貫徹,鞏固已得的政權,黨需要使自己經常保持強大,需要掌握國家機關中的某些樞紐,這一切都是很自然的。但是在全國範圍內,不論大小單位,甚至一個科一個組,都要安排一個黨員做頭兒,事無巨細,都要看黨員的顏色行事,都要黨員點了頭才算數,這樣的做法,是不是太過分了一點? …

Isn’t the Party acting as though [it is back in the past when rulers as though] ‘The Whole Kingdom is Ours’, creating thereby a monopoly whereby One Family Rules All Under Heaven? In my opinion, a mentality supporting the ‘Party Empire’ is the main source of factionalism in China today, the basic source of conflicts between the Party and those outside the Party. … Lately [as part of the Hundred Flowers period of open criticism of the Party] lots of people have spoken out against the novices in the monastery; no one has raised their voice against the Old Abbots.

黨這樣做,是不是「莫非王土」那樣的思想,從而形成了現在這樣一個一家天下的清一色局面。我認為,這個「黨天下」的思想問題是一切宗派主義現象的最終根源,是黨和非黨之間矛盾的基本所在。… 最近大家對小和尚提了不少意見,但對老和尚沒有人提意見。

— Chu Anping, 1 June 1957

People’s Daily, 2 June 1957

trans. G.R. Barmé

***

***

Chu Anping’s initial hesitation proved justified: the public outpouring against monopoly Party control in which he had been pressured to participate was deemed to be a counter-revolutionary rightist plot against the Communist Party. Mao decried it as ‘a frenzied attack on the Party determined to turn China into a bourgeois country’.

Like tens of thousands of others, Chu was now labelled an enemy of the people. Stripped of his editorial job only months after having taken it on and, after years of humiliation, he mysteriously disappeared in 1966. Family members were only able to commemorate this celebrated journalist at a ceremony in his hometown of Yixing, Jiangsu province, in May 2015. Since Chu’s body had never been found, instead of a tomb the family had to be satisfied with what is known as a ‘mound for clothes and cap’ 衣冠塚. It contained some of Chu’s personal effects. Family members paid homage at the site in the traditional manner.

Although long dead, today Chu Anping is among the small number of ‘Unrehabilitated Rightists’ who remain stimatised, part of what is known as the ‘Zhang [Bojun]–Luo [Longji] Alliance’ 張羅同盟: their threat to the Party in 1956-1957 is still used to justify the Anti-Rightist Purge and intellectual freedom in China today. That nationwide attack on independent thought, criticism and dissent was, in 1978, eventually re-evaluated for having ‘gotten out of hand’ 擴大化. But it still marked a major moment in how the party-state exercised ideological control over the country, that it was launched by Mao Zedong himself and stage-managed by Deng Xiaoping with the support of ideologues like Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun afforded it an abiding iconic, and practical, status. Each subsequent purge of ‘bourgeois thinking’ or ‘anti-Party sentiment’ — and there have been many — has been carried out in the shadow of 1957 (see Deng’s 15 July 1981 comments on the subject, quoted below).

Some politically astute mainland scholars have attempted to claim Chu for the party-state on the grounds that he was, after all, essentially a patriot. Fatuous gestures that exploit the memory of a major writer who was murdered by Party caprice are, however, overshadowed by Chu Anping’s lasting public legacy, a powerful three-word expression that describes the politics of China in 2018 just as aptly as it did in 1957:

黨天下

The Party Empire.

***

Sources:

- Dai Qing, Chu Anping and ‘The Party Empire’ 儲安平與「黨天下」, 北京: 中國華僑出版社, 1989

- Geremie R. Barmé, Using the Past to Save the Present: Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent, East Asian History, Issue 1 (June 1991): 141-181

- Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992, pp.360-361, with additions and emendations.

- 儲安平, 向毛主席和周總理提些意見, 人民日報,1957年6月2日

***

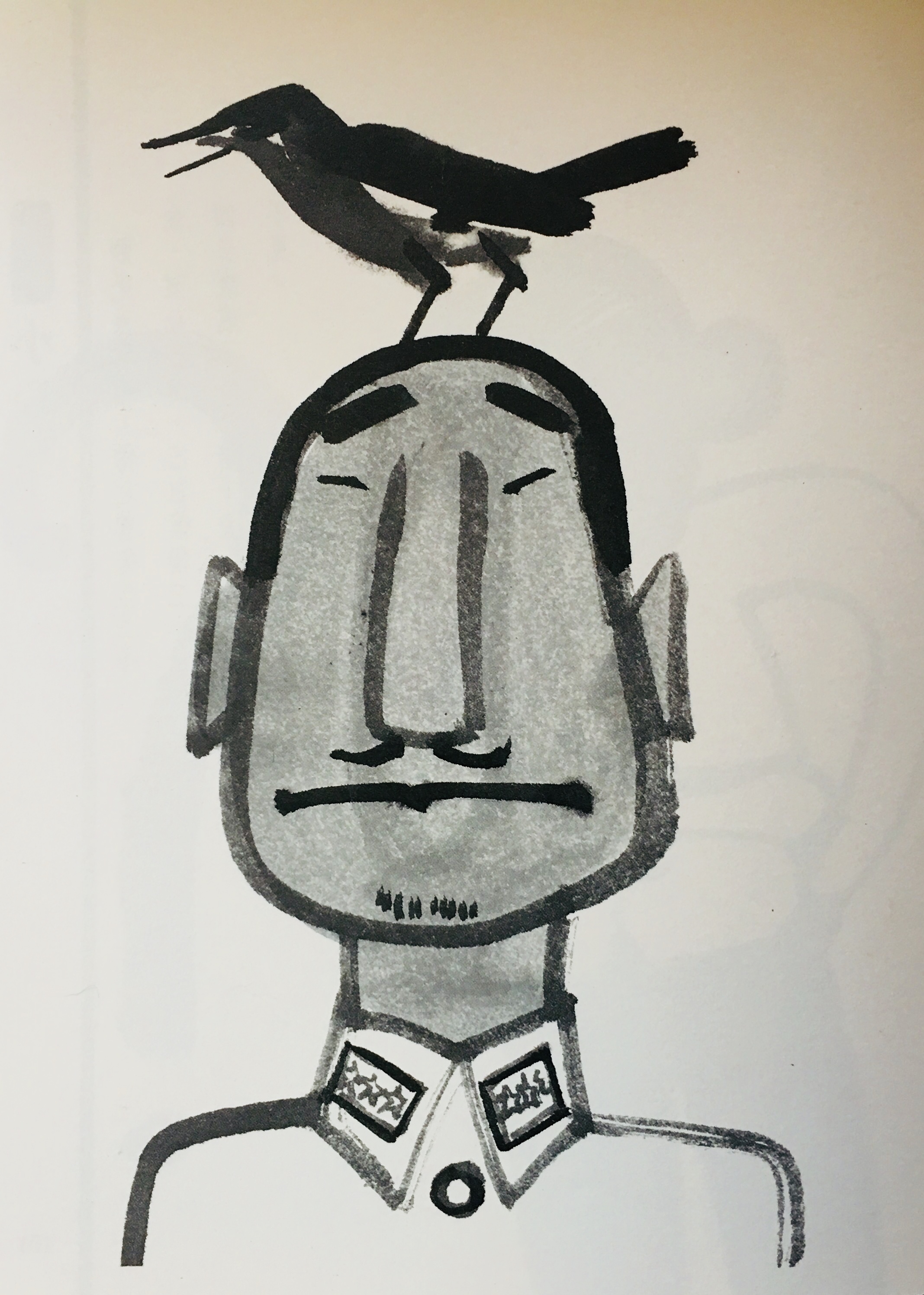

Outfoxed 狐教子

Huang Yongyu 黃永玉

It was a warm day and the air was bracing. A Old Fox wanted to give his son some training, so he instructed him to jump off a cliff. The Young Fox was too scared even to look down, but the Old Fox called out:

‘Don’t worry, I’m here to catch you!’

He leaned forward as if ready to catch his son. Emboldened, the Young Fox hurled himself off the cliff, but his father stepped aside and he hit the ground with a thud. The Young Fox wailed:

‘You lied to me. What kind of father are you?’

Rubbing his paws together, the Old Fox replied:

‘Though I’m your father, with the world the way it is you need to learn that you can’t trust anyone.’

Herewith the First Lesson of the Fox: Don’t forget it!

是日日暖气爽,狐令其子自三十仞巖上躍下,鍛其技能。子惴惴然不敢俯視。狐仰而告之曰:勿懼!余固於此接應。且以前爪作接應之狀。子乃奮然躍下,而老狐閃於一旁,任其子下墜,嘭然有聲,子痛泣曰:謊余若是,爾其非余父否?狐撫掌答曰:然也,世上事,親莫如父亦不可信。此狐之教義第一課,牢記勿忘。

— trans. G.R. Barmé

To Sunder the Party-State

1980

Following Mao’s death in September 1976, the launching of reform programs under his successor Hua Guofeng 華國鋒 and then, in December 1978, the formal reorientation of the Party so that henceforth it would focus on economic reforms, the leadership made tentative moves to uncouple the highly centralised Party system from the governing of the state. The Party leaders had been chastened by the disastrous misrule of Mao, and their own complicity in it, from the 1950s. Responsible for the death of tens of millions of people and the callous defiling of the lives of hundreds of millions more it was time both before reflection, and action. Now, under the aegis of Deng Xiaoping, a raft of reforms were launched, and the ensuing debate about if and how to sunder the party from the state would continue throughout the 1980s.

In March 2018, there were protests about the latest round of revisions of the Chinese Constitution, ones that would ostensibly allow for the lifelong tenure of state leaders. These moves appeared to many to negate the hard-won lessons of the past and earlier attempts by the Party leadership to limit their power and ambitions. While many referred to the 1982 revision of the National Constitution that had set term limits on state leaders (touched on below in ‘Constitutional Interlude, IV: 1982’), the locus classicus for post-Mao policies can be found in a speech that Deng Xiaoping made in 1980 titled On the Reform of the System of Party and State Leadership.

When, on 24 July 2018, the Tsinghua University professor of law Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 published his plea to the party-state leadership — Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes 我們當下的恐懼與期待 — he was, by implication, also referring to this speech. As Deng said in his address to an enlarged meeting of the Political Bureau on 18 August 1980:

Why is the Central Committee proposing … changes in the leadership of the State Council?

- First of all, it is not good to have an over-concentration of power. It hinders the practice of socialist democracy and of the Party’s democratic centralism, impedes the progress of socialist construction and prevents us from taking full advantage of collective wisdom. Over-concentration of power is liable to give rise to arbitrary rule by individuals at the expense of collective leadership, and it is an important cause of bureaucracy under the present circumstances.

- Second, it is not good to have too many people holding two or more posts concurrently or to have too many deputy posts. There is a limit to anyone’s knowledge, experience and energy. If a person holds too many posts at the same time, he will find it difficult to come to grips with the problems in his work and, more important, he will block the way for other more suitable comrades to take up leading posts. Having too many deputy posts leads to low efficiency and contributes to bureaucracy and formalism.

- Third, it is time for us to distinguish between the responsibilities of the Party and those of the government and to stop substituting the former for the latter. Those principal leading comrades of the Central Committee who are to be relieved of their concurrent government posts can concentrate their energies on our Party work, on matters concerning the Party’s line, guiding principles and policies. This will help strengthen and improve the unified leadership of the Central Committee, facilitate the establishment of an effective work system at the various levels of government from top to bottom, and promote a better exercise of government functions and powers.

- Fourth, we must take the long-term interest into account and solve the problem of the succession in leadership. As precious assets of the Party and state, the older comrades shoulder heavy responsibilities. Their primary task now is to help the Party organizations find worthy successors to work for our cause. This is a solemn duty. It is of great strategic importance for us to ensure the continuity and stability of the correct leadership of our Party and state by having younger comrades take the ‘front-line” posts while the older comrades give them the necessary advice and support. … …

As far as the leadership and cadre systems of our Party and state are concerned, the major problems are bureaucracy, over-concentration of power, patriarchal methods, life tenure in leading posts and privileges of various kinds.

Bureaucracy remains a major and widespread problem in the political life of our Party and state. Its harmful manifestations include the following: standing high above the masses; abusing power; divorcing oneself from reality and the masses; spending a lot of time and effort to put up an impressive front; indulging in empty talk; sticking to a rigid way of thinking; being hidebound by convention; overstaffing administrative organs; being dilatory, inefficient and irresponsible; failing to keep one’s word; circulating documents endlessly without solving problems; shifting responsibility to others; and even assuming the airs of a mandarin, reprimanding other people at every turn, vindictively attacking others, suppressing democracy, deceiving superiors and subordinates, being arbitrary and despotic, practising favouritism, offering bribes, participating in corrupt practices in violation of the law, and so on. Such things have reached intolerable dimensions both in our domestic affairs and in our contacts with other countries. … …

Over-concentration of power means inappropriate and indiscriminate concentration of all power in Party committees in the name of strengthening centralized Party leadership. Moreover, the power of the Party committees themselves is often in the hands of a few secretaries, especially the first secretaries, who direct and decide everything. Thus ‘centralized Party leadership’ often turns into leadership by individuals. This problem exists, in varying degrees, in leading bodies at all levels throughout the country. Over-concentration of power in the hands of an individual or of a few people means that most functionaries have no decision-making power at all, while the few who do are overburdened. This inevitably leads to bureaucratism and various mistakes, and it inevitably impairs the democratic life, collective leadership, democratic centralism and division of labour with individual responsibility in the Party and government organizations at all levels. This phenomenon is connected to the influence of feudal autocracy in China’s own history and also to the tradition of a high degree of concentration of power in the hands of individual leaders of the Communist Parties of various countries at the time of the Communist International. Historically, we ourselves have repeatedly placed too much emphasis on ensuring centralism and unification by the Party, and on combating decentralism and any assertion of independence. And we have placed too little emphasis on ensuring the necessary degree of decentralization, delegating necessary decision-making power to the lower organizations and opposing the over-concentration of power in the hands of individuals. … …

Tenure for life in leading posts is linked both to feudal influences and to the continued absence of proper regulations in the Party for the retirement and dismissal of cadres. The question of retirement did not arise during the period of revolutionary wars when we were all still young, nor in the fifties when we were all in the prime of life, but it was unwise of us not to have solved the problem later.

Deng Xiaoping 鄧小平

On the Reform of the System of

Party and State Leadership

黨和國家領導制度的改革

18 August 1980

- Emphasis added by The Editor.

Beijing, 1979

These moves to modulate, and to reaffirm creatively, one-party rule, developed as pent-up discontent found a voice in Beijing. From late 1978 through 1979, protests against Party autocracy, and its continued secretive sway over the country, were expressed in wall posters, speeches and samizdat publications. In late 1979, having served a purpose in the context of Party factional infighting, the outpouring of discontent was shut down, key dissidents were arrested and new regulations banning public experssions of discontent were proposed by the Party and endorsed by the usual pliant constitutional bodies.

In March 1979, Deng Xiaoping, with the advice and guidance of ideologues like Hu Qiaomu (a man he despised, but one on whom he relied on for his unique skills as what he called ‘The Party’s Pen’ 黨內的一支筆桿, and Deng Liqun), announced Four Cardinal Principles 四項基本原則 that would ensure the continued unity between party and state:

- The principle of upholding the socialist path;

- The principle of upholding the people’s democratic dictatorship;

- The principle of upholding the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party; and,

- The principle of upholding Mao Zedong Thought and Marxism-Leninism.

The Four Cardinal Principles would be challenged by outspoken intellectuals, writers, journalists and students, first in 1983, again in late 1986 and, most notably, in 1989 when a nationwide Protest Movement led by rebellious university students in Beijing called for a range of freedoms. Ironically, on the eve of the protests in April 1989, the party-state had secretly mooted the removal of the Four Cardinal Principles from the Preamble to the Constitution as a prelude to a new approach to long-stalled politial reform. The Beijing Massacre of 4 June 1989, and the ousting of Zhao Ziyang, the Party General Secretary who had replaced his liberal predecessor Hu Yaobang (purged in January 1987), ended all discussion of substantive political change in China. The party-state was further entrenched, and it has remained so ever since.

***

Problems on the Ideological Front

Deng Xiaoping

15 July 1981

A short time ago I told Comrade Hu Yaobang that I wanted to talk with the propaganda departments about problems on the ideological front, especially those in literature and art. The Party’s leadership on this front — including literature and art — has achieved noteworthy success. This should be affirmed. But certain tendencies towards a crude approach and over-simplification cannot be ignored or denied. However, a more important problem at present, I think, is laxity and weakness and a fear of criticizing wrong trends. As soon as you criticize something, you are accused of brandishing a big stick. It is very hard nowadays for us to carry out criticism, let alone self-criticism. Self-criticism is one of the three major features of our Party’s style of work, one of the chief characteristics distinguishing our Party from other political parties. For quite a number of our people, however, it now seems difficult to practise.

Prior to the Sixth Plenary Session of the Central Committee [late June 1981], the General Political Department of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army raised the question of criticizing the film script Unrequited Love 苦戀 [loosely based on the life of the artist Huang Yongyu 黃永玉, whose artwork features in China Heritage, this script, and the film made from it, mentioned below, cast doubt on the nature of the ‘party-state’, that is, whether loving China meant that one also had to support the Communist Party]. I have been taken aback by some other things I’ve read recently too:

- A young poet made an irresponsible speech at Beijing Normal University. Some students commented that although the Party organization had done a lot of ideological and political work among the students, that speech blew it all away. The university Party committee was aware of this matter but took no measures. It was a woman student who wrote a letter to the Party committee criticizing our weak ideological work.

- Recently in Urumqi, Xinjiang, a person in charge of the preparatory group for the formation of the local federation of writers and artists talked a lot of nonsense. Many of his views went far beyond certain wrong, anti-socialist statements criticized during the anti-Rightist struggle of 1957.

There are many other examples. To put it in a nutshell, these people want to abandon the road of socialism, break away from Party leadership and promote bourgeois liberalization. Let us recall the 1957 experience. It was incorrect then to broaden the scope of the anti-Rightist struggle, but it was necessary to oppose the Rightists. You will certainly all remember how aggressive some Rightists were. So are some people today. We are not going to launch an anti-Rightist campaign again. But on no account should we give up serious criticism of erroneous trends. …

Some persons now fancy themselves as heroes. Before they were criticized, they didn’t attract much attention. But once they were criticized, they began to be sought after. This is an abnormal phenomenon and we must work seriously to eradicate it. Its social and historical background can be traced mainly to the 10-year turmoil of the ‘Cultural Revolution’; it is also connected with corrosion by bourgeois ideology from abroad. We must analyse each case concretely. At present, the main problem is not so much the existence of this phenomenon as the fact that we are too soft in handling it. There is laxity and weakness. Of course, in solving current problems, we should learn from past experience and refrain from launching a movement. We must analyse each case on its merits and treat each person who has made errors appropriately, according to the nature and seriousness of the mistakes. Methods of criticism must be studied. Arguments must hit the nail on the head. We must not resort to converging attacks and movements. But there must be ideological work, criticism and self-criticism. We must not lay aside the weapon of criticism.

After that young poet delivered his speech at Beijing Normal University, some students said that if we allowed things to go on this way, our country would be ruined. He took a position opposite to ours. I have seen the movie Sun and Man 太陽和人, which follows the script of Unrequited Love. Whatever the author’s motives, the movie gives the impression that the Communist Party and the socialist system are bad. It vilifies the latter to such an extent that one wonders what has happened to the author’s Party spirit. Some say the movie achieves a fairly high artistic standard, but that only makes it all the more harmful. In fact, a work of this sort has the same effect as the views of the so-called democrats.

The essence of the Four Cardinal Principles is to uphold Communist Party leadership. Without Party leadership there definitely will be nationwide disorder and China would fall apart. History has shown us this. Chiang Kai-shek was never able to unify China. The keystone of bourgeois liberalization is opposition to Party leadership. But without Party leadership there will be no socialist system. In confronting these problems, we must not take the old path and resort to political movements. We must, however, make appropriate use of the weapon of criticism. …

Just imagine what sort of influence Sun and Man would have if shown to the public. Someone has said that not loving socialism isn’t equivalent to not loving one’s motherland. Is the motherland something abstract? If you don’t love socialist New China led by the Communist Party, what motherland do you love? We do not ask all our patriotic compatriots in Hong Kong and Macao and in Taiwan and abroad to support socialism, but at the least, they should not oppose socialist New China. Otherwise, how can they be called patriotic? Of every citizen — and every young person — living under the leadership of the government in the People’s Republic of China, however, we demand more.

Above all, we demand that writers, artists and ideological and theoretical workers in the Communist Party observe Party discipline. Yet today many of our problems stem from inside the Party. If the Party can’t discipline its own members, how can it lead the masses? We insist on the policy of ‘letting a hundred flowers bloom, a hundred schools of thought contend’, and on handling contradictions among the people correctly. This will remain unchanged. True, the ‘Left’ tendency still exists in the guidance of our ideological and cultural work, and we must resolutely guard against it and correct it. But that certainly doesn’t mean we should stop practising criticism and self-criticism. The main way to correctly handle contradictions among the people is to start from the desire for unity, carry out criticism and self-criticism and arrive at a new unity. The policy of ‘letting a hundred flowers bloom, a hundred schools of thought contend’ cannot be separated from the practice of criticism and self-criticism. In criticizing, we must be democratic and reason things out, but criticism should never be dismissed offhand as using the ‘big stick’. We must get clear on this whole question of criticism and self-criticism, for it is important in bringing along the next generation. …

Since we began stressing the need to uphold the Four Cardinal Principles, comrades in our ideological circles have become clearer in their thinking. Because of this and also because of the resolute steps taken to get rid of illegal organizations and publications, the situation has improved. But we must remain on the alert. …

— Summary of a talk with

leading comrades of the

Central Propaganda Departments

- Emphasis added by The Editor.

***

Constitutional Interlude, IV

1982

In December 1982, the National People’s Congress considered amendments to the 1975 Constitution, which was itself a revision of the 1954 document. In 1975, Mao had made a range of proposals that institutionalised the Cultural Revolution. (Deliberations to do with those revisions began in 1970 and they had led to a struggle over the position of State President and other issues related to Mao’s ‘hand-picked’ successor, the ill-fated Lin Biao.) This time around, the changes were made at the suggestion of Deng Xiaoping, supported by other Party leaders and ideologues like Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun. They included a significant addition to the Preamble. It now affirmed the legal status of the Four Cardinal Principles:

Under the leadership of the Communist Party of China and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, the Chinese people of all nationalities will continue to adhere to the people’s democratic dictatorship and follow the socialist road, steadily improve socialist institutions, develop socialist democracy, improve the socialist legal system, and work hard and self-reliantly to modernize industry, agriculture, national defence, and science and technology step by step to turn China into a socialist country with a high level of culture and democracy.

This stipulation, like Article 6 in the 1977 Constitution of the Soviet Union (mentioned in Constitutional Interlude, V: 1989, below) effectively circumscribed other democratic freedoms and basic human rights that were theoretically granted to all Chinese citizens.

Section 2, Article 79 of the revised 1982 Constitution stated that:

The President and Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China are elected by the National People’s Congress. Citizens of the People’s Republic of China who have the right to vote and to stand for election and who have reached the age of 45 are eligible for election as President or Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China. The term of office of the President and Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China is the same as that of the National People’s Congress, and they shall serve no more than two consecutive terms.

***

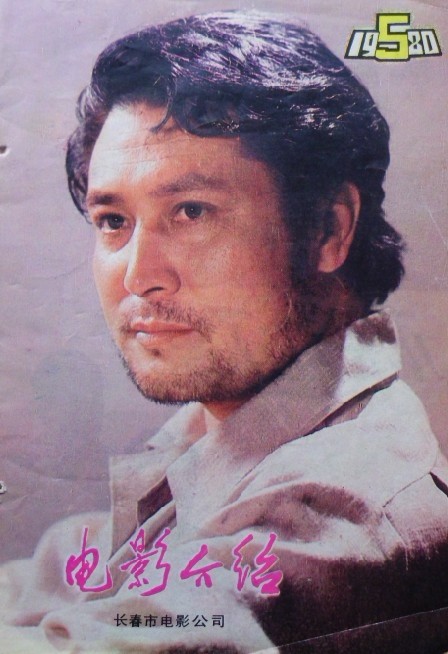

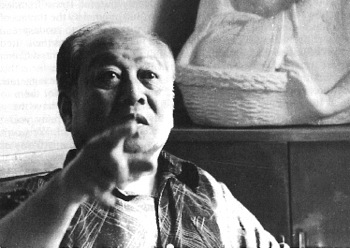

Wu Zuguang & The Layabouts Lodge

1986

The Layabouts Lodge 二流堂 was the name given to a building owned by a wealthy Burmese Chinese known among his friends as A Lang 阿郎, the pet-name of Tang Yu (唐瑜, 1912-2010). Tang enjoyed a successful career in publishing and film, as well as being able to rely on the generous support of wealthy relatives outside China. In turn he was unstinting in providing the struggling artistic talents of the wartime Nationalist capital of Chongqing with food and lodging. His house became, avant la lettre, the Chelsea Hotel of the city.

On one occasion the unfailingly pro-Communist Party writer Guo Moruo 郭沫若 and Xu Bing 徐冰, the Chongqing-based Party United Front Department representative, visited Tang’s artist-packed house; both men were shocked and bemused to find that many of its near one dozen denizens were still in bed. These ‘cultural youth’ were for the most part men and women involved in theatre and journalism; they slept late and rose even later. The rather stuff Communist literatus Guo Moruo used the slang term èrliúzi 二流子 (‘slouch’, ‘scoundrel’, ‘wastrel’, ‘ne’er-do-well’, or ‘slacker’) — an expression from Yan’an and the northern Shaanxi 陝北 Communist-base area that had recently become popular — to describe the unruly mob and the name stuck. Thereafter, Tang’s house became known as The Layabouts Lodge 二流堂.

Wu Zuguang and other free-thinking and, in fact, first-rate talents and minds frequently gathered at Tang Yu’s house. These members of The Layabouts Lodge were patriotically minded and increasingly critical of the corrupt and authoritarian rule of the Nationalist Party and its dictatorial party-state. They enjoyed a shared language of jokes, literary allusions and political humour. Over years of friendship, reading and an appreciation of each other’s work, or just through the exchange of doggerel verse or political gossip, they developed their own particular argot. Theirs was indeed like a secret lodge.

We should make no mistake, the members of The Layabouts Lodge were by in large ‘progressive’ cultural figures, which meant that they were attracted to and eventually actively engaged with the Communist Party during the war years. After all, both then and during the Civil War of 1946-1949, outside Yan’an the Party promoted itself as a positive force for democratic renewal and humane modernity. As we mentioned earlier, in countless public statements, speeches, press reports and editorials Party leaders emphasised time and again that when in power the Communists would finally bring to China political pluralism, democracy, freedom of speech and other basic human rights.

It was via this United Front strategy, various practical measures, and through the tireless work of ‘agents of influence’ — intellectuals, artists, charismatic political figures and propagandists — that many non-aligned members of China’s elite were won over to the cause, if not as Communists then at least as fellow travellers. The Party was so successful in convincing countless cultural patriots that it was worthy of their trust that key members of this group would later remind the Party whenever they were given an opportunity, that it should keep to its end of the bargain and bring democracy and freedom to their country. One of the most prominent and outspoken of these was Wu Zuguang, whose story is featured below.

***

A Disaffected Gentleman

The annotated translation of Xu Zhangrun’s Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes 我們當下的恐懼與期待 is dedicated to the memory of Wu Zuguang 吳祖光, a playwright and essayist who, after he was free to do so, famously spoke out against the Personality Cult of Mao Zedong and one-party rule in China. In wartime Chongqing, Zuguang, an active playwright and member of The Layabouts Lodge, also edited the Evening Arts Supplement of New Citizens News 新民報晚刊. It is a historical irony truly worthy of the name that Zuguang also happened to be the man who first published Mao Zedong’s most famous poem ‘Snow’ 雪, which featured in Drop Your Pants! (Part I) — Ruling The Rivers & Mountains.

After 1949, Zuguang, who for a time was the darling of the new Communist cultural establishment, kept up contact with his old friends. In the mid 1950s, when members of his informal cultural salon unwittingly found themselves embroiled in the purge of the Hu Feng Clique discussed earlier, Zuguang himself was identified as clandestinely operating his own anti-party group, the ‘Wu Zuguang Clan’ 吳祖光小家族集團. A relatively innocuous gathering of aspiring writers, theatre critics and humourists, the clan was an affront to Party decorum. Zuguang paid for general outspokenness when he participated in the Hundred Flowers Campaign, the nationwide political movement that also claimed Chu Anping as a victim. Like tens of thousands of others Zuguang took up the call to help the Party help itself and, among other things, he observed that the overlordship of the Communist Party was not conducive to the Chinese cultural scene. After all, he asked, did the famous Tang poets Li Bo 李白 and Du Fu 杜甫 have commissars looking over their shoulders? As the hundred flowers wilted Zuguang was silenced and, in 1957, he was dispatched to the Great Northern Wilderness to undergo a period of labour reform.

Following the Cultural Revolution, the authorities instituted a policy that encouraged leading writers, scientists and other members of the educated elite to join the ranks of the Communist Party itself. Recently exonerated for his earlier outspokenness, Zuguang wanted to prove a point by joining up in 1980. Despite his membership in an organisation known for jealously guarding its intellectual ‘droit du seigneur‘, Zuguang maintained his independence and became a vocal critic of the Party’s erratic cultural policy.

In 1983, while travelling in America, Wu went against Party discipline by criticising the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign which, orchestrated by Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun, two Party ideologues the reader will recall from the Yan’an Rectification Campaign discussed in Drop Your Pants! (Part I), was aimed at curbing dangerous liberalising tendencies in the society (see Gloria Davies, Discursive Heat, China Heritage, 30 July 2018). Upon returning to China, he organised a petition calling for a halt to such ideological purges.

In 1986, Zuguang championed the cause of the banned play WM · 我們, shut down after twenty-three performances for its negative view of life (it was finally revived in 2008). He also criticised doctrinaire ideologues like Hu Qiaomu who called for this and other bans on cultural works, and even berated them for being too spineless to admit openly that they had done so. All of this was in the 1980s, an era of relative cultural efflorescence, one which, during every loosening of the party-state political duopoly allowed for tremours of ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ 資產階級自由化. People took advantage of these moments of release to enjoy freedoms not available since 1949, ones that have all too often been curtailed since 1989.

— The Editor

***

***

Cultural Assassins

Wu Zuguang 吳祖光

1986

The following is taken from remarks Wu Zuguang made at a meeting held in 1986 to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Mao’s ‘Double Hundred’ (or Hundred Flowers) policy speech. — Ed.

The crux of the matter is that it is all too common for people in power to say one thing but do another; or even do the exact opposite of what they’ve said. Then they get away scot free, regardless of how disastrous their actions may have proven to be. Ours is a land with thousands of years of feudal history behind it, where people habitually accept the right of might rather than the importance of democracy and law. The leaders and those they lead are often in a relationship of obvious inequality. Add to this the fact that over the last few decades it has been the ‘fashion’ to denounce and purge people. For example, just after the ‘Double Hundred’ Policy was announced [by Mao Zedong in 1956], encouraging intellectuals to make political statements and criticize the Party, a nationwide movement aimed at obliterating the very intellectuals who had done just that was launched, with the most frightening consequences. The number of people who suffered is incalculable, and this was but the first in a series of vile campaigns. There’s a famous saying of the feudal philosopher Mencius: If a lord treats his ministers like dirt, then his ministers will regard him as ‘bandit and enemy’. It shows that Mencius understood the relationship between the rulers and the ruled. Surprisingly even after all these years, there are many leaders who don’t understand this simple principle. They treat the masses like dirt, see them as slaves and fools; at the same time they train a group of opportunistic flatterers vicious, double-faced rogues, as their intimates and strong-arm men: Decades of this situation have led to the near-extinction of integrity. The atmosphere of duplicity at one point brought New China to the verge of collapse, and it has still not been dispelled.

From my experience, the aims of any level of feudal dictator [in the apparat] are completely incompatible with the aims of the so-called Double Hundred Policy. These dictators are like Qin Shihuang [the first emperor of China], they can’t countenance any opposition within their sphere of control. They can only accept fawning and compliance. They appear stern and powerful on the surface, but in reality their every moment is spent in dread that they may lose their grasp on power. So it is inevitable that they feel threatened by anyone who does not agree with them entirely, worst of all the intellectuals, who think speak and write.

Intellectuals have suffered like this for the past thirty years. Every political movement has been aimed at intellectuals first. The arts world in particular has been the first victim in every campaign. This is because intellectuals are not trusted…

— June 1986

trans. Geremie Barmé

Source:

- 吳祖光, ‘實現「雙百」方針有點希望了’, 《九十年代月刊》, 1987: 9; translated in Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, edited by G. Barmé and John Minford (2nd ed., New York: Hill & Wang, 1988), pp.368-372, with minor emendations.

***

‘Three Good Reasons for Quitting the Party’, below, is an excerpt from a letter Wu Zuguang addressed to the Central Disciplinary Commission of Communist Party Central. Zuguang composed it after the ever-present ideologue Hu Qiaomu made a personal visit.

Hu’s visit was prompted by an ongoing Party attack on ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ that had been launched in early 1987 at the time of the dismissal of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang. His lax policies were blamed for an anti-Party groundswell among intellectuals and university students that led, in December 1986, to student protests in Shanghai. Rebelling against one-party rule the students agitated for freedom of association and freedom of the press. Immediately thereafter, on Deng Xiaoping’s orders, a number of leading ‘public intellectuals’ (the term was unknown at the time) were denounced and expelled from the Party. Hu Qiaomu participated in the purge by denouncing Hu Yaobang (who had previously approved the arrest of Qiaomu’s son on charges of corruption) and, along with Deng Liqun, he led the propaganda offensive.

— The Editor

***

Three Good Reasons for

Quitting the Party

Wu Zuguang 吳祖光

1987

Although entirely unmoved by the criticisms of my ‘errors’ and dumbfounded by the extraordinary fashion in which I was requested to quit the Party-privately and without any scope for discussion — I acquiesced to Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu’s request on the spot. I had three reasons for doing so:

- Respect for the aged is a glorious Chinese national tradition. I have always treated my elders with respect. Comrade Qiaomu is a man rich in years and frail of health. To be the humble object of his magnanimous attention, indeed to be the cause of such exertion on his part — he had to climb up the four flights of stairs to reach my unworthy hovel! — caused me the greatest unease. For this reason I said to Comrade Qiaomu: ‘This decision has taken me completely by surprise, and I cannot understand it. But, as you have come here to present this request to me in person, I will accept it.’

- At the time my first thought was: as a Party member it is my duty to uphold the credibility of the Party. In the documents issued by Party Central this year, and in many speeches of the leaders of the Centre over the last months, it has been repeatedly stated that following the expulsion of those three people [the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi 方勵之 and the writers Liu Binyan 劉賓雁 and Wang Ruowang 王若望] earlier in the year, no other comrades would be expelled from the Party. Only two weeks ago, on 16 July to be exact … Comrade Qiaomu … repeatedly emphasised that there wouldn’t be a fourth expulsion [of anyone from the Party]. ‘Who said there would be a fourth? Who is the fourth?’ The words still seem to be ringing in my ears. Needless to say, I felt both devastated and sick at heart when I realized that I could inadvertently become that Fourth Man. The document [read to me by Hu Qiaomu] stated that if I did not relinquish my Party membership voluntarily, I would be expelled. I didn’t refuse, since that would have forced the Party to expel me, and once again the credibility of the Party would suffer in the eyes of the people of China and the whole world. Because of the extremely unconvincing nature of the document [demanding my resignation] I realised that it would lead many people in our society overly to sympathise with me. Again, this would be highly deleterious to the Party. Indeed, in the past ten days I have become the object of numerous well wishes, something that is very painful for me. The last thing I want is to become a newsmaker. Of course, there are also some comrades who will have nothing more to do with me.

- There is one more reason, one that I am most unwilling to give voice to, and it pains me much to do so. I have decided to resign from the Party because I am disillusioned with some of its decisions.

The Communist Party of China has a glorious tradition. It has achieved great things; it revived the confidence of our nation, it is a Party to which the people of China are deeply grateful. It was founded and grew to strength at a time when it was surrounded by the threats of capitalism and feudalism. It went from isolation to widespread support, from weakness to strength, and finally having sent the united forces of imperialism, warlords and landlords packing, it united China (apart from Taiwan). The Communist Party defeated capitalism, this is a fact that is plain to all. So I see absolutely no need to exaggerate the threat of the bourgeoisie today, for it is no easy thing for them to infect the body of the proletariat. The Chinese people have been educated and immunised by the Communist Party for many years; they are capable of warding off the infections of capitalism. We won’t be corrupted by the bourgeoisie. To my mind the Communist Party of China was always an energetic and fearless organization, not one that was scared of criticism or lacking in self-confidence. Capitalism and the bourgeoisie are nothing to be scared of, nor for that matter is the student movement. After all, the two great student movements of modern Chinese history — the May 4 [1919] and December 9 [1935] Movements — were both led by the Communist Party of China [sic] …

The Communist Party of China always had the magnanimity to accept criticism humbly. Only when all manner of ideas and the wisdom of the broad masses are accepted can the great task of reunifying China be achieved. I first came under the guidance of the Party in the 1940s, so I have had personal experience of this. ‘When a gentleman is told of his faults he is delighted, when he hears of the goodness [of others] he pays them his respects’ — this is one of the traditional strengths of the Chinese. However, starting in the late 1950s, some leaders in Party Central would only listen to pleasing words of praise, and became increasingly annoyed by criticism. For many years now, it is the most loyal and outspoken intellectuals who have been denounced, their lives destroyed. The numerous political movements have had an inestimable and devastating effect on a huge number of China’s most outstanding talents. The results have been tragic. Although the Party has attempted to change, it is all too evident that up to now it hasn’t been able to do so.

— August 1987

trans. Geremie Barmé

Source:

- 吳祖光, ‘至中紀委書’, 《鏡報》, 1987: 9; translated in Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, edited by G. Barmé and John Minford (2nd ed., New York: Hill & Wang, 1988), pp.368-372, with minor emendations.

***

***

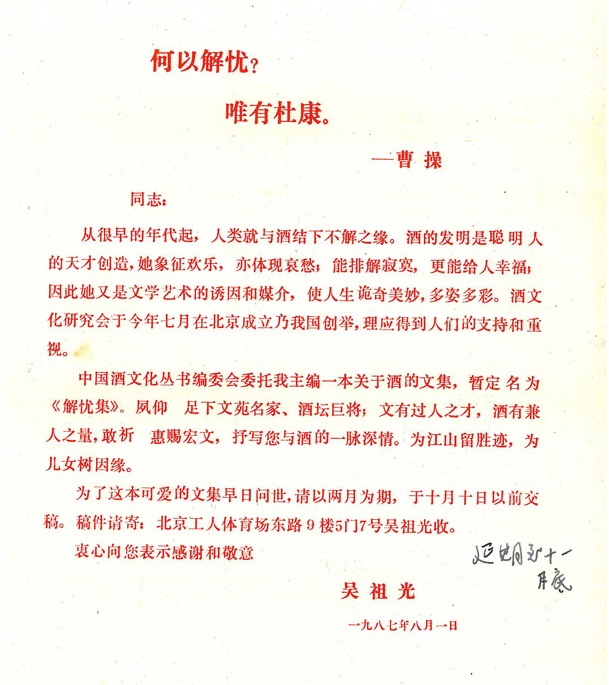

After quitting the Party on 1 August 1987, Zuguang composed a different kind of letter: an invitation calling on friends to contribute to a collection of Essays on Dispelling Despondency 解憂集. The titled was inspired by a famous line from Cao Cao 曹操:

How does one dispel despondency?

Wine, only wine.

何以解憂,唯有杜康。

He soon found himself inundated by letters of congratulation and support, as well as numerous gifts of wine and spirits 酒 sent to celebrate his ‘liberation’. As he was a teetotaller, Zuguang asked a neighbourhood restaurant to put his ‘Post-Party Alcohol’ 退黨酒 on display. Over the following months, I was among the many friends who helped dismantle that display.

In October 1987, Wu Zuguang was invited to participate in the Twentieth Anniversary of the Iowa International Writers’ Program. He remained outspoken in his criticisms of the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalism Campaign. In one interview he declared:

‘I know I can be a good human being,

but it’s impossible for me to be

a good Party member too.’

***

Further Reading:

- Wine 酒 and Commemorating Yang Xianyi 楊憲益, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 25 (March 2011)

Constitutional Interlude, V

1989

Political reforms in the Republic of China on Taiwan during the last years of the life of Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國, 1910-1988), the son of Chiang Kai-shek who had inherited the mantle of leadership of the Nationalist Party in 1975, emboldened some mainland activists to hope for a similar strong leader who could ensure economic prosperity, social stablilty and gradual political reform in the People’s Republic. As had been the case of the former party-state on Taiwan, such a ‘new authoritarian’ might usher in a gradual political revolution.

The proponents of what in 1988-1989 was known New Authoritarianism 新權威主義 failed to find the right authoritarian, and crucially overlooked key pressures on Chiang to reform (such as, the increased strength of Taiwanese 本土 advocates of change and positive US political pressure), but the debate about enlightened autocracy would resurface around the time of Xi Jinping’s rise in 2012.

***

In the lead up to the Beijing Protest Movement of April-June 1989, it was believed that during the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress an amendment sponsored by Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang and other Party leaders, would be put forward to remove the Four Cardinal Principles from the Preamble of the document. Some well-connected public figures like Dai Qing, as well as Party insiders like Hu Qiaomu, leaked information about the proposal. (Li Rui 李銳 later reported that Hu, a man who always did the bidding of the leadership, told friends that including the Principles in the constitution was, in essence, unconstitutional.)