Contra Trump

移裔

In the conclusion of the inaugural address he delivered in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C. on 20 January 2025, Donald J. Trump, the 47th President of the United States of America, declared that ‘The future is ours, and our golden age has just begun.’ He earlier claimed that:

We will be a nation like no other, full of compassion, courage, and exceptionalism. Our power will stop all wars and bring a new spirit of unity to a world that has been angry, violent, and totally unpredictable.

America will soon be greater, stronger, and far more exceptional than ever before.

I return to the presidency confident and optimistic that we are at the start of a thrilling new era of national success. A tide of change is sweeping the country, sunlight is pouring over the entire world, and America has the chance to seize this opportunity like never before.

When writing about the ‘Golden Age’ 盛世 that the Chinese authorities began celebrating some two decades ago I observed that:

General wisdom, or common sense, would suggest that to declare a particular period or an era to be a Golden or Prosperous Age before it is over may be ill advised. It is often a fraught proposition to determine whether a renaissance is underway in the midst of a period of rapid socio-cultural change. And that begs the question whether frenetic economic activity is the ne plus ultra of human endeavour.

As is so often the case with heroic figures, pivotal historical moments, crises, tipping-points and so on, the passage of time, a greater understanding of the complex interaction of politics and society, as well as culture and economics, individuals and mere happenstance, all contribute to more nuanced, if not ‘correct’, evaluations of a certain epoch. In China’s modern history, however, enlightenments, rebirths and revivals have often been hastily announced and hailed in a mood of anxious exuberance. This often happens long before conclusions based on temperate reflection following a decent interval, measured understanding and deep reflection, can be drawn.

Eighteen months after I wrote these words, China ushered in what I call Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

China Heritage marked the second inauguration of Donald Trump by asking Can we call it fascism yet? We concluded with a Springtime for Elon, a parody of Springtime for Hitler: A Gay Romp With Adolf and Eva at Berchtesgaden, a fictional musical play within a play in Mel Brooks’ 1967 film The Producers along with famously gnomic line from Douglas Adams:

So long, and thanks for all the fish.

***

Below we quote a passage from The Golden Door: Letters to America, a ‘frilly, funny valentine’ to the United States published by A.A. Gill in 2013, only a few years before his death in 2016. At the time, Gill was a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and a critic and features writer for The Sunday Times in London. As Michiko Kakutani observed of Gill, he was ‘a writer with several octaves to his voice, capable of being outrageous and lyrical, comic and profane, crotchety and meditative. At his best, he writes with enormous energy and verve, channeling Evelyn Waugh and Clive James, and this volume certainly has its share of entertaining anecdotes and sparkling asides.’

Kakutani was not impressed by Gill’s often sentimental account of America, a country with which he had deep familial ties, pointedly remarking that he did ‘little to shed new light on such perennial topics as the contradictions in the American soul, torn between materialism and idealism, hedonism and puritanism, individuality and conformity. Nor does he grapple with the current political partisanship that has so divided the country, or with growing concerns about America’s decline on the world stage.’

‘Perhaps’, Kakutani remarks, ‘the most provocative thing in “To America With Love” is Mr. Gill’s European take on our history of immigration. He argues that America over the years has been a magnet, drawing “the young and the strong from Europe; the adventurous, the clever, and the skilled.”

In the United States, “immigration is the story of hope and achievement, of youth, of freedom, of creation,” he writes. “But all entrances on one stage are exits elsewhere. In Europe it is loss. Every one a farewell, a failure, a sadness, a defeat.” Between 1800 and 1914, he says, “more than 30 million Europeans immigrated to the New World: one in four Irishmen, one in five Swedes, three million Germans, five million Poles, four million Italians. There is not a country, a community, a village or household that wasn’t affected by the lure of the West.”

As Mr. Gill sees it, much of the bitterness that animates trans-Atlantic relationships (Europeans, he says, patronize America “for being a big, dumb, fat, belligerent child”) can be traced back to this dynamic. “The belittling, the discounting, the mocking of the States is not about them at all,” he writes. “It’s about us, back here in the ancient, classical, civilized continent.”

Europe’s view of America, he contends, “has been formed and deformed by the truth that we are the ones who stayed behind, for all those good, bad and lazy reasons: because of caution, for comfort, for conformity and obligation, but mostly, I suspect, because of habit and fear. We didn’t take the risky road.”

In the first year of Trump 2.0, ‘the story of hope and achievement, of youth, of freedom, of creation’ that underpinned the modern history of immigration in the United States, is being challenged by the radical regime in the White House.

We conclude with an essay by

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

25 January 2025

Golden Age of Trump, Day Five

***

America, Europe’s Greatest Invention

A.A. Gill

‘Stupid, stupid. Americans are stupid. America is stupid. A stupid, stupid country made stupid by stupid, stupid people.” I particularly remember that because of the nine stupids. It was said over a dinner table by a professional woman, a clever, clever, clever woman. Hardback-educated, bespokely traveled, liberally humane, worked in the arts. I can’t remember specifically why she said it, what evidence of New World idiocy triggered the trope. Nor do I remember what the reaction was, but I don’t need to remember. It would have been a nodded and muttered agreement. Even from me. I’ve heard this cock crow so often I don’t even feel guilt for not wringing its neck.

Among the educated, enlightened, expensive middle classes of Europe, this is a received wisdom. A given. Stronger in some countries like France, less so somewhere like Germany, but overall the Old World patronizes America for being a big, dumb, fat, belligerent child. The intellectuals, the movers and the makers and the creators, the dinner-party establishments of people who count, are united in the belief—no, the knowledge—that Americans are stupid, crass, ignorant, soul-less, naïve oafs without attention, irony, or intellect. These same people will use every comforting, clever, and ingenious American invention, will demand America’s medicine, wear its clothes, eat its food, drink its drink, go to its cinema, love its music, thank God for its expertise in a hundred disciplines, and will all adore New York. More than that, more shaming and hypocritical than that, these are people who collectively owe their nations’ and their personal freedom to American intervention and protection in wars, both hot and cold. Who, whether they credit it or not, also owe their concepts of freedom, equality, and civil rights in no small part to America. Of course, they will also sign collective letters accusing America of being a Fascist, totalitarian, racist state.

Enough. Enough, enough, enough of this convivial rant, this collectively confirming bigotry. The nasty laugh of little togetherness, or Euro-liberal insecurity. It’s embarrassing, infectious, and belittling. Look at that European snapshot of America. It is so unlike the country I have known for 30 years. Not just a caricature but a travesty, an invention. Even on the most cursory observation, the intellectual European view of the New World is a homemade, Old World effigy that suits some internal purpose. The belittling, the discounting, the mocking of Americans is not about them at all. It’s about us, back here on the ancient, classical, civilized Continent. Well, how stupid can America actually be? On the international list of the world’s best universities, 14 of the top 20 are American. Four are British. Of the top 100, only 4 are French, and Heidelberg is one of 4 that creeps in for the Germans. America has won 338 Nobel Prizes. The U.K., 119. France, 59. America has more Nobel Prizes than Britain, France, Germany, Japan, and Russia combined. Of course, Nobel Prizes aren’t everything, and America’s aren’t all for inventing Prozac or refining oil. It has 22 Peace Prizes, 12 for literature. (T. S. Eliot is shared with the Brits.)

And are Americans emotionally dim, naïve, irony-free? Do you imagine the society that produced Dorothy Parker and Lenny Bruce doesn’t understand irony? It was an American who said that political satire died when they awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger. It’s not irony that America lacks; it’s cynicism. In Europe, that arid sneer out of which nothing is grown or made is often mistaken for the creative scalpel of irony. And what about vulgarity? Americans are innately, sniggeringly vulgar. What, vulgar like Henry James or Eleanor Roosevelt or Cole Porter, or the Mormons? Again, it’s a question of definitions. What Americans value and strive for is straight talking, plain saying. They don’t go in for ambiguity or dissembling, the etiquette of hidden meaning, the skill of the socially polite lie. The French in particular confuse unadorned direct language with a lack of culture or intellectual elegance. It was Camus who sniffily said that only in America could you be a novelist without being an intellectual. There is a belief that America has no cultural depth or critical seriousness. Well, you only have to walk into an American bookshop to realize that is wildly wrong and willfully blind. What about Mark Twain, or jazz, or Abstract Expressionism?

What is so contrary about Europe’s liberal antipathy to America is that any visiting Venusian anthropologist would see with the merest cursory glance that America and Europe are far more similar than they are different. The threads of the Old World are woven into the New. America is Europe’s greatest invention. That’s not to exclude the contribution to America that has come from around the globe, but it is built out of Europe’s ideas, Europe’s understanding, aesthetic, morality, assumptions, and laws. From the way it sets a table to the chairs it sits on, to the rhythms of its poetry and the scales of its music, the meter of its aspirations and its laws, its markets, its prejudices and neuroses. The conventions and the breadth of America’s reason are European.

This isn’t a claim for ownership, or for credit. But America didn’t arrive by chance. It wasn’t a ship that lost its way. It wasn’t coincidence or happenstance. America grew tall out of the cramping ache of old Europe.

When I was a child, there was a lot of talk of a “brain drain”—commentators, professors, directors, politicians would worry at the seeping of gray matter across the Atlantic. Brains were being lured to California by mere money. Mere money and space, and sun, and steak, and Hollywood, and more money and opportunity and optimism and openness. People who took the dollar in exchange for their brains were unpatriotic in much the same way that tax exiles were. The unfair luring of indigenous British thought would, it was darkly said, lead to Britain falling behind, ceasing to be the pre-eminently brilliant and inventive nation that had produced the Morris Minor and the hovercraft. You may have little idea how lauded and revered Sir Christopher Cockerell, the inventor of the hovercraft, was, and you may well not be aware of what a noisy, unstable waste of effort the hovercraft turned out to be, but we were very proud of it for a moment.

The underlying motif of the brain drain was that for real cleverness you needed years of careful breeding. Cold bedrooms, tinned tomatoes on toast, a temperament and a heritage that led to invention and discovery. And that was really available only in Europe and, to the greatest extent, in Britain. The brain drain was symbolic of a postwar self-pity. The handing back of Empire, the slow, Kiplingesque watch as the things you gave your life to are broken, and you have to stoop to build them up with worn-out tools. There was resentment and envy—whereas in the first half of the 20th century Britain had spent the last of Grandfather’s inherited capital, leaving it exhausted and depressed, for America the war had been the engine that geared up industry and pulled it out of the Depression, capitalizing it for a half-century of plenty. It seemed so unfair.

The real brain drain was already 300 years old. The idea of America attracted the brightest and most idealistic, and the best from all over Europe. European civilization had reached a stasis. By its own accounting, it had grown from classical Greece to become an identifiable, homogeneous place, thanks to the Roman Empire and the spread of Christianity. Following the Dark Ages, there was the Renaissance and the Reformation, and then the Age of Reason, from which grew a series of ideas and discoveries, philosophies and visions, that became pre-eminent. But at the moment of their creation here comes the United States—just as Europe was reaching a point where the ideas that moved it were outgrowing the conventions and the hierarchies that governed it. Democracy, free economy, free trade, free speech, and social mobility were stifled by the vested interests and competing stresses of a crowded and class-bound continent. Migration to America may have been primarily economic, but it also created the space where the ideas that in Europe had grown too root-bound to flourish might be transplanted. Over 200 years the flame that had been lit in Athens and fanned in Rome, Paris, London, Edinburgh, Berlin, Stockholm, Prague, and Vienna was passed, a spark at a time, to the New World.

In 1776 the white and indentured population of America was 2.5 million. A hundred years later it was nearly 50 million. In 1890, America overtook Britain in manufacturing output to become the biggest industrial economy in the world. No economy in the history of commerce has grown that precipitously, and this was 25 years after the most murderous, expensive, and desperate civil war. Indeed, America may have reached parity with Britain as early as 1830. Right from its inception it had faster growth than old Europe. It now accounts for a quarter of the world’s economy. It wasn’t individual brains that made this happen. It wasn’t a man with a better mousetrap. It was a million families who wanted a better mousetrap and were willing to work making mousetraps. It was banks that would finance the manufacture of better mousetraps, and it was a big nation with lots of mice.

One of the most embarrassing things I’ve ever done in public was to appear—against all judgment—in a debate at the Hay Literary Festival in the mid-90s, speaking in defense of the motion that American culture should be resisted. Along with me on this cretin’s errand was the historian Norman Stone. I can’t remember what I said—I’ve erased it. It had no weight or consequence. On the other side, the right side, were Adam Gopnik, from The New Yorker, and Salman Rushdie. After we’d proposed the damn motion, Rushdie leaned in to the microphone, paused for a moment, regarding the packed theater from those half-closed eyes, and said, soft and clear, “Be-bop-a-lula, she’s my baby, / Be-bop-a-lula, I don’t mean maybe. / Be-bop-a-lula, she’s my baby, / Be-bop-a-lula, I don’t mean maybe. / Be-bop-a-lula, she’s my baby love.”

It was the triumph of the sublime. The bookish audience burst into applause and cheered. It was all over, bar some dry coughing. America didn’t bypass or escape civilization. It did something far more profound, far cleverer: it simply changed what civilization could be. It set aside the canon of rote, the long chain letter of drawing-room, bon-mot received aesthetics. It was offered a new, neoclassical, reconditioned, reupholstered start, a second verse to an old song, and it just took a look at the view and felt the beat of this vast nation and went for the sublime.

There is in Europe another popular snobbery, about the parochialism of America, the unsophistication of its taste, the limit of its inquiry. This, we’re told, is proved by “how few Americans travel abroad.” Apparently, so we’re told, only 35 percent of Americans have passports. Whenever I hear this, I always think, My good golly gosh, really? That many? Why would you go anywhere else? There is so much of America to wonder at. So much that is the miracle of a newly minted civilization. And anyway, European kids only get passports because they all want to go to New York.

***

Source:

- A.A. Gill, America, Europe’s Greatest Invention—and How the New World Exceeds the Old, Vanity Fair, July 2013

***

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

— Emma Lazarus, 1849-1887

***

Contra Trump

& America’s Empire of Tedium

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

- An Elegiac Eulogy from Unf*cking The Republic

- The American Green Zone in Our Consciousness

- Those 107 Days

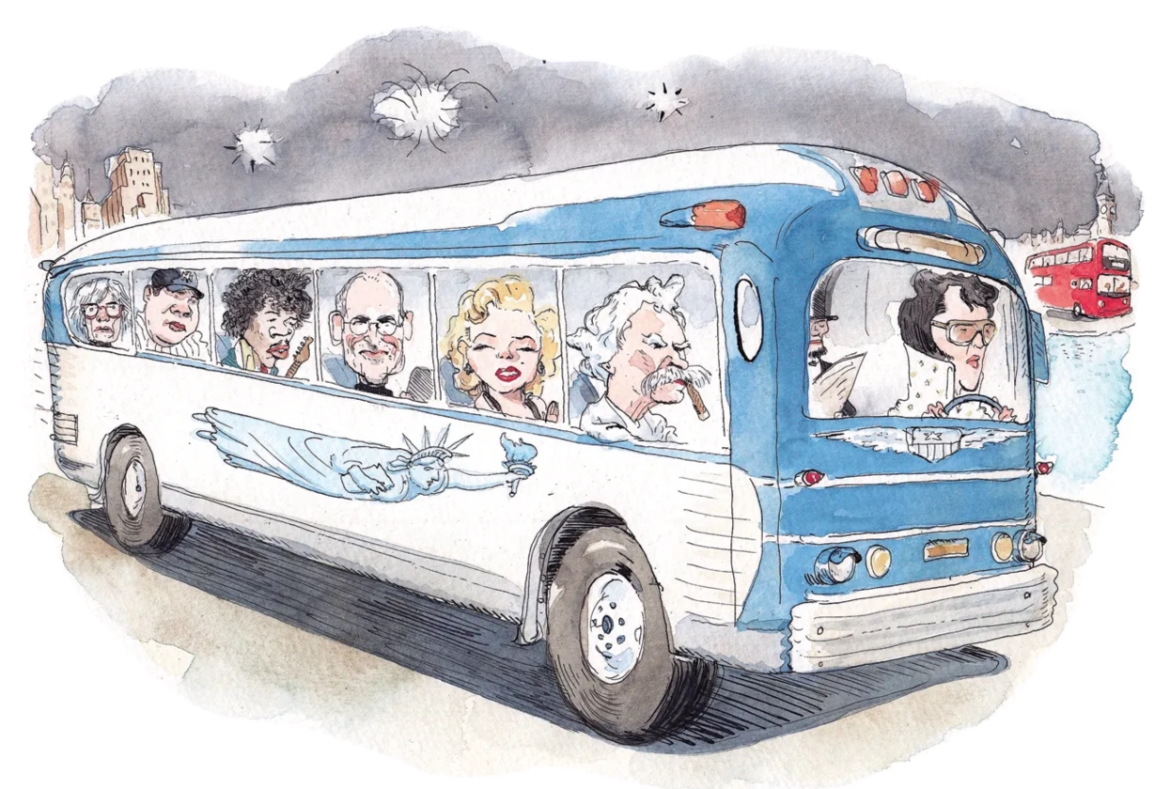

- ‘I Think I’m Gonna Hate It Here’ — Randy Rainbow introduces the clown-car cabinet of MAGADU

- 6 January 2021 to 6 January 2025: America’s Slow-burn Autogolpe

- T2 – A Feature, Not a Bug

- Trump’s Inauguration — Can we call it fascism yet?

***

A Dark Reminder of What American Society Has Been and Could Be Again

How an obsessive hatred of immigrants and people of color and deep-seated fears about the empowerment of women led to the Klan’s rule in Indiana.

It is common, when some atrocious statement or action born of hatred comes to the fore, to hear people solemnly intone, “This is not who we”—meaning Americans—“are.” That sentiment leans heavily on the most idealistic vision of the United States, expressed most familiarly in our Declaration of Independence—the truths that “we hold” about equality and “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Of course, aspirations are necessary to strengthen the characters of individuals and societies. But it is equally important to face reality about weaknesses and flaws that contend with the will to be a better person or a better society. One of the best things about studying history is that it allows us to see examples of both tendencies, and to be vigilant about the choices we make.

This year, I served as a judge for the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award. Timothy Egan’s A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them received an honorable mention in recognition of its over-all excellence and timeliness. Why is it especially timely? Because it tells the story of how an obsessive hatred of immigrants and people of color and deep-seated fears about the empowerment of women led to the rise of a form of fascism in Indiana.

I knew this story from a class I took in college. Back then, I saw it as a fantastical tale from a never-to-be-repeated past. Now, at a moment when hostility toward immigrants has reached a fever pitch in some quarters—“A caravan from Mexico is coming,” “They’re eating people’s pets”—and when disrespect for women’s bodily autonomy is driving policy proposals, what happened in Indiana back in the Jazz Age is a sobering reminder of just what American society has been and could be again.

The book recounts the harrowing story of the Ku Klux Klan’s dominance of nineteen-twenties Indiana. The Klan controlled the entire state, largely through the machinations of one man: David C. (D. C.) Stephenson. A grifter originally from Texas, Stephenson became the Grand Dragon of the Indiana chapter. Although he never held an official government position, at the apex of his power he could proclaim, without irony, “I am the law.” And many of the freeborn citizens of the American republic had no problem living under his dictates, even as he blighted the lives of their fellow-citizens.

The Klan had a strong presence in other states, too. Egan notes that the group “was the largest and most powerful of the secret societies among American men—bigger by far than the Odd Fellows, the Elks, or the Freemasons, and vastly greater in number than the original Klan born in violence just after the Civil War.” In 1925, in a show of force, thousands of Klansmen marched in Washington. But the situation in Indiana was notable for having a single charismatic figurehead to whom many people eagerly pledged their allegiance.

Stephenson helped put the governor of the state, the Klansman Ed Jackson, in office. He controlled police departments, judges, and politicians, and he allied with them to promote the Klan’s interests, which included terrorizing people whom he considered insufficiently American. He insisted that none of this was about hate; it was simply a matter of promoting Americanism. The presumptive outsiders included all nonwhite people, immigrants, Catholics, and Jews. Stephenson had his own private police force of thirty thousand men, who were given the authority to enforce the Klan’s “law” by means of physical intimidation.

I venture that when most people today think of the Klan they imagine a relatively small and distinct cadre of men who emerged in the night to burn crosses in the woods or, occasionally, to drag Black people from their homes for lynching. The notion that the Klan could operate as openly and as brazenly as its members did in Indiana, using the government as an arm of the so-called Invisible Empire without significant opposition, says a lot about what is possible in this country.

I found myself wondering about the role of the press during Stephenson’s ascendancy: Did the Fourth Estate do its job in exposing the extralegal control over Indiana? For the most part, it did not, except for one journalist, who, after writing about the state’s shadow government, was assaulted by Stephenson’s henchmen and jailed. (In truth, many members of the press didn’t report on the Klan because they were sympathetic to the organization.)

What broke the spell that Stephenson held over so many Indianans? It’s not that people came to their senses about the threat that he posed. It turns out that, in addition to being a grifter and an authoritarian, he was a murderer. In 1925, with the aid of his followers, he kidnapped a young woman named Madge Oberholtzer. According to Egan’s book, he sexually assaulted Oberholtzer and savagely bit her body, creating wounds that became infected. Some combination of those lacerations, and the poison she took in an attempted suicide when left alone by her kidnappers, led to her death. She lived long enough to give a statement about what had happened to her. The sensational trial and the public airing of details about the Klan destroyed Stephenson, who was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. In the coming years, the system under which the Klan operated unravelled.

There’s no reason to think that the animosity toward immigrants and the determination to control women that sustained the Klan and Stephenson ever dissipated. Instead, in the years after Oberholtzer’s murder, people hid evidence of their association with the Klan and their enthusiasm for the man whom the law exposed as a monster. It is no surprise that the sentiments stoked during that period are still present, waiting to be aroused by the next authoritarian with a vision of “Americanism.” What happened in Indiana could happen again, on a national scale.

***

Source:

- Annette Gordon-Reed, A Dark Reminder of What American Society Has Been and Could Be Again, The New Yorker, 7 November 2024