Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XXVIII

週而復始

In early March 2020, we published an interview with the Beijing sociologist Guo Yuhua 郭於華 under the title The Political Manipulation of People is More Toxic Than Any Virus. It was included as a chapter in Viral Alarm China Heritage 2020, a series which also featured When Fury Overcomes Fear by Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 and Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go by Xu Zhiyong 許志永 (translations of both of these essays first appeared in ChinaFile).

In the editorial introduction to the translation of Guo Yuhua’s interview, we observed that Guo addressed the coronavirus epidemic in the context of China’s systemic limitations. She directed her comments at the fundamental question of intrinsic human worth and the value of the individual, a recurring issue throughout modern Chinese history.

‘You [the party-state] want to frustrate the attempts of civilian actors to volunteer independent support [to those dealing with the epidemic]’, Guo told Radio Free Asia. In the meantime the state pursues a ‘unified command-and-control approach to the situation, but you simply cannot control everything so you end up exacerbating what is already a man-made disaster.’

That’s why we can observe that this kind of system and the way it thinks about the world as a whole is based on an approach that regards people as nothing more than utilitarian objects [or political tools; that is, as merely the means to an end], something to be subjected to management and control. Such a thing is in and of itself a kind of virus; it’s a governance system that is no less deadly than the coronavirus itself. Personally, I think it’s even more toxic. …

Given that the system is so powerful that it can maintain a tight rein on absolutely everything while never feeling constrained to accept responsibility for any of its mistakes, do you think I am hopeful that it might suddenly become motivated to reform itself? It doesn’t want to give up anything and it will never relinquish power. This is what we have: an extreme version of a 360-degree autocracy.

Moreover, today it has everything on its side, including the latest in high-tech ways and means. This equips it to do things far beyond anything anyone outside the system might be able to imagine. That’s why I’m both furious and desperate — I simply can’t see any way out whatsoever!

This, then, is the nub of all of China’s problems. The present coronavirus crisis has revealed the true nature of the system from inside and out. The other day, I made an observation in a WeChat group that if, even after all that has happened, people still refuse to see what’s really going on then they’re simply ‘incurable’.

— from Guo Yuhua, The Poison in China’s System, China Heritage, 6 March 2020

Individual worth and human autonomy have been topics of concern to China’s Communists, and their opponents, since the Yan’an Rectification Campaign of the early 1940s (see Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, China Heritage, 8 August 2018). They were again taken up by Mao and his theoreticians in the early 1950s and remained a central feature of the Maoist remolding of China thereafter.

After Mao’s death, the question of humanism and human value, and concomitant issues like human rights, would be a focus of the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign of 1983-1984 (see Spiritual Pollution Thirty Years On, The China Story, 17 November 2013) and a prelude to the crushing of the mass protests of 1989.

The Communist Party’s view of human worth, particularly its usefulness in achieving and maintaining political power, has been consistently, and narrowly, utilitarian and inhumane, as well as anti-humanist. As Guo Yuhua pointed out, this remains the case to this day.

***

An op-ed essay published in The New York Times on 10 December 2022 recalls the initial response of the Chinese government to the epidemic:

A People’s Daily article breathlessly described China’s anti-Covid campaign in military terms — a “battle” or “fight” that was repeatedly described as “thrilling.” The same piece quoted Mr. Xi, who urged his countrymen to understand the pandemic as proof of their superiority.

“The fight against the novel coronavirus pandemic has achieved major strategic results,” Mr. Xi said, “fully demonstrating the significant advantages of the leadership of my country’s Communist Party and our country’s socialist system.”

Xiao Qiang, a University of California, Berkeley, research scientist who focuses on technology, information and censorship in China, told me: “Chinese people were getting the message every day: ‘Look, this is our systematic advantage, we can centralize power, we can coordinate everything, and that’s why China is better.’” He added: “it widened into his complete political message: ‘That’s why you need a Xi Jinping, that’s why he needs to stay in power.’”

— Megan K. Stack, A Contagion the U.S. and China Both Fear: Each Other, The New York Times, 10 December 2022

As Yanzhong Huang, also writing in The New York Times, said:

… a nationwide outbreak at this point could be dire. If one-quarter of the Chinese population is infected within the first six months of the government letting its guard down — a rate consistent with what the United States and Europe experienced with Omicron — China could end up with an estimated 363 million infections, some 620,000 deaths, 32,000 daily admissions to intensive-care units and a potential social and political crisis. Three punishing years fighting off the coronavirus would have been in vain, leaving China with the worst-case scenario it has struggled so hard to avoid.

— Yanzhong Huang, China’s Struggle With Covid Is Just Beginning, The New York Times, 4 December 2022

Although there were numerous signs of widespread disquiet during the first months of the epidemic in 2020, years of repression and censorship meant that articulate voices of protest were relatively few in number, and they were easily silenced. Today, as China’s Covid crisis starts in earnest in December 2022, below we recall what two of those voices had to say.

***

For students of the Xi Jinping personality cult — one that we have characterised as being more about cult than about personality — the collapse of Xi’s signature ‘zero-Covid’ policy has been a study in arrogance and obfuscation. At no point during the epidemic has Xi ‘manned up’ and addressed the nation about the crisis directly. In December 2022, as the populace, long misled by Xi boosterism and state misinformation, grappled with on-the-ground confusion and Covid panic, Xi remained aloof and silent. Meanwhile, having instilled fear and vaccination hesitancy for over two years, his propagandists launched a campaign of doublethink, declaring that the new radically modified anti-coronavirus policies ‘in no way signal a relaxation of our Covid response, let alone do they signify a complete opening up or so-called “giving in and giving up”.’ (See When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022.)

‘Chairman Xi’s New Clothes’, the subtitle of this appendix in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, is a reference to Chairman Mao’s New Clothes, an unsparing account of the Cultural Revolution by Simon Leys that was published in 1971. The subtitle also refers to critiques of Xi Jinping made by Xu Zhiyong and Ren Zhiqiang 任志強 in early 2020 in which they mocked ‘The People’s Leader’ for ‘wearing an emperor’s new clothes’. Their temerity landed both men in jail.

‘In My Beginning is My End’, the main title of this appendix, is from Four Quartets, a series of poems by T.S. Eliot. It refers to the interconnected and circular nature of life and time. For his part, Xi Jinping is obsessed with political cycles.

The first stanza in East Coker, Part II of Eliot’s four-part poem, reads:

In my beginning is my end. In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

Which is already flesh, fur and faeces,

Bone of man and beast, cornstalk and leaf.

Houses live and die: there is a time for building

And a time for living and for generation

And a time for the wind to break the loosened pane

And to shake the wainscot where the field-mouse trots

And to shake the tattered arras woven with a silent motto.

***

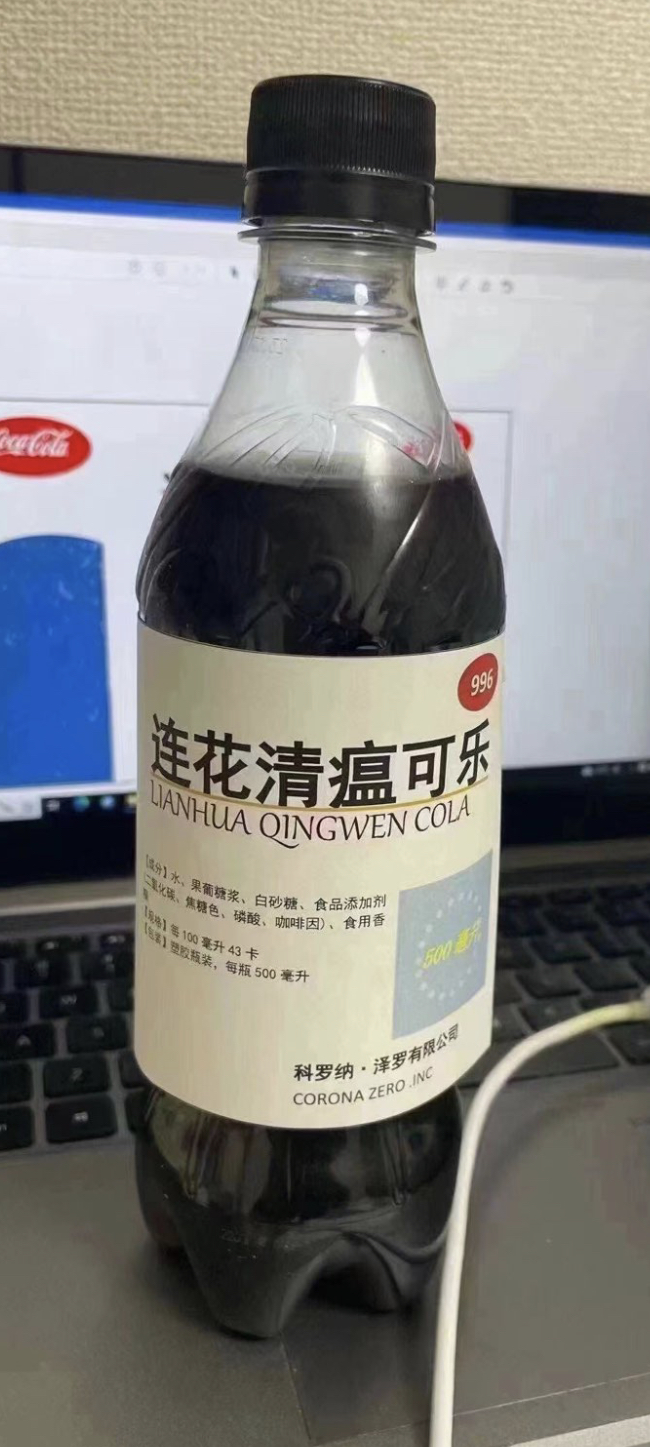

I am grateful to Jianying Zha 查建英 for introducing me to ‘Lianhua Qingwen Cola’ 連花清瘟可樂, a fantasy beverage concocted for nightmarish times.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

13 December 2022

***

Further Reading

- Trustee Chair, Exiting Zero-Covid: China’s Provincial Covid-19 Rules Tracker, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 9 December 2022

From Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- The Curse of Great Leaders — the Xi Jinping decade and beyond, 20 July 2022

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022

- When Zig Turns Into Zag the Joke is on Everyone, 12 December 2022

From Viral Alarm:

- ‘The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud’, China Heritage, 10 March 2020

- Ren Zhiqiang 任志強, ‘Denunciation of Xi Jinping: stripping the clothes of a clown who is determined to be emperor’ 剝光了衣服堅持當皇帝的小丑, Matters, 2020年4月1日 (for a partial translation, see Josh Rudolph, ‘Essay by Missing Property Tycoon Ren Zhiqiang’, China Digital Times, 13 March 2020

- Zhao Shilin 趙士林, ‘Gengzi Memorial to the Throne’, ‘庚子上書’, 《中國數字時代》, 2020年3月9日

- Xu Zhiyong 許志永, ‘Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go’, ChinaFile, 26 February 2020

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華, ‘The Poison in China’s System’, China Heritage, 6 March 2020

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear’, China Heritage, 24 February 2020

Gare du Midi

W.H. Auden

A nondescript express in from the South,

Crowds round the ticket barrier, a face

To welcome which the mayor has not contrived

Bugles or braid: something about the mouth

Distracts the stray look with alarm and pity.

Snow is falling, Clutching a little case,

He walks out briskly to infect a city

Whose terrible future may have just arrived.

Kool-Aid with Chinese Characteristics

996 Lianhua Qingwen Cola, manufactured by Corona Zero Inc, a spoof libation for the corona crisis. Contains: water, high-fructose syrup, white sugar, food additives, nitrogen dioxide, caramel coloring agent, phosphoric acid, caffeine and edible food essence. (‘996’ in the name of the beverage is a reference to oppressive workplace practices that require employees to be in the office from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm, six days, or 72 hours, a week.)

Throughout China’s ongoing coronavirus epidemic, Lianhua Qingwen 連花清瘟, a traditional medical concoction used for treating influenza, has been heavily promoted for its efficacy in treating the virus. Controversy surrounds this home-grown prophylactic and its mass distribution in China, including Hong Kong, as well as the role played by Zhong Nanshan (鐘南山, 1936-). A pulmonologist known to be one of Xi Jinping’s ‘Covid whisperers’, Zhong was also reported to have a financial interest in Yiling Pharmaceutical, a leading manufacturer of Lianhua Qingwen, something that he has denied. In August 2020, Zhong was awarded the prestigious Medal of the Republic for his efforts in combatting the SARS epidemic as well as Covid. In December 2020, Zhong Nanshan was invited to unveil a bronze statue of himself at the Affiliated High School of South China Normal University on the occasion of its 132nd anniversary.

On 9 December 2022, Zhong averred that south China would return to pre-Covid normality by mid 2023.

— The Editor

***

China’s Coronavirus Crisis Is Just Beginning

Xi Jinping’s handling of the epidemic is reviving political dissent.

3 March 2020

Geremie R. Barmé

a New York Times op-ed

The Chinese Communist Party has always been quick to congratulate itself for how it deals with crises, be they natural disasters or catastrophes of its own making. The coronavirus epidemic is no exception, even now that it has become a global health emergency. The government of China’s first response to the deadly virus, detected in late December, was dilatory at best, willfully negligent at worst, and yet the party promptly lavished praise on the state, particularly on China’s president, Xi Jinping.

“Seeking Truth,” the party’s leading theoretic journal, recently celebrated the fact that the “People’s Leader” had handled the disaster with unflappable confidence, proving himself to be not only “the guiding light of China and the backbone of 1.4 billion Chinese,” but also a “calming balm” for a world whose nerves had been jangled by the outbreak.

Judging by the hyperbole, it would seem that the party’s or the president’s own nerves have been badly jangled. With good reason. Not since Charter 08, the manifesto by Liu Xiaobo and other activists that called for constitutional reform more than a decade ago, has the Chinese Communist Party faced such a pointed challenge from its political critics.

In early February, as party propagandists were preparing a book-length paean to Mr. Xi’s crisis management skills — “A Battle Against Epidemic: China Combating Covid-19 in 2020” (also to be published in English, French, Spanish, Russian and Arabic) — two well-known critics of China’s party-state published searing analyses of what the outbreak really exposed.

Xu Zhangrun, a law professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, posted this assessment online: “The coronavirus epidemic has revealed the rotten core of Chinese governance; the fragile and vacuous heart of the jittering edifice of state has thereby been revealed as never before.”

Since early 2016, Xu Zhangrun has been publishing speeches and essays warning of the perils that China is inviting by turning away from substantive economic and political reform and instead reaffirming the Chinese Communist Party’s dominance. His work is usually widely read in China — until it is censored. But thanks to its broad circulation in international Chinese-language media, it gets recirculated on the mainland in the form of digital samizdat, and is frequently quoted in WeChat discussions.

In what arguably is his most famous critique of the Xi government, which was published online in China in July 2018, Xu Zhangrun had written: “The gunpowder-like stench of militant ideology has become stronger.” He had decried attempts to mythologize Mr. Xi like Mao Zedong was many decades before: “We need to ask why a vast country like China, one that was previously so ruinously served by a personality cult simply has no resistance to this new cult.”

And ruinously it is served again today, with the coronavirus epidemic. Xu Zhangrun wrote of Mr. Xi in his essay last month: “The price for his overarching egotism is now being paid by the nation as a whole.”

For Xu Zhangrun, the current crisis is only the latest in a series of policy failures — including Beijing’s handling of the trade war with the United States and the pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong — that highlight the deficiencies of an authoritarian system that has increasingly concentrated power in the hands of one man:

“Don’t you see that although everyone looks to The One for the nod of approval, The One himself is clueless and has no substantive understanding of rulership and governance, despite his undeniable talent for playing power politics?”

“The political life of the nation is in a state of collapse and the ethical core of the system has been hollowed out,” Xu Zhangrun declares in his elegant signature prose, which rings with classical cadences. “The ultimate concern of China’s polity today and that of its highest leader is to preserve at all costs the privileged position of the Communist Party and to maintain ruthlessly its hold on power.”