The Tower of Reading

木猶如此,人何以堪。

This is the first chapter in Zhong Shuhe’s selections from New Tales of the World 世說新語 in Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts. It offers a meditation on the fleeting nature of time and the mutability of human existence.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a series inspired by the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our interpretive translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年). The short title for this endeavour in China Heritage is simply The Tower of Reading.

Each chapter features a short Classical Chinese text of under 100 characters which Zhong translates into modern Chinese. To these Zhong appends ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, both modern terms for such works that are akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or a particular incident. Often, Zhong’s comments are whimsical reflections on his life.

The Tower of Reading in China Heritage offers translations of the classical texts and of Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive essays along with the original Chinese versions of both.

For more on the background to this project, see Introducing The Tower of Reading.

***

This chapter is the first of eleven selections from New Tales of the World 世說新語, ascribed to Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444 CE). This famous and popular fifth-century selection of anecdotes, stories and witticisms, is known in English translation as A New Account of the Tales of the World.

We introduce New Tales of the World with a short essay by Richard Mather, the scholar who translated the full text (although, in The Tower of Reading, we offer our own version of the passages selected). This is followed by Zhong Shuhe’s comment on an anecdote about power, time and mutability. Since Zhong refers to Wang Xizhi’s immortal preface the Orchid Pavilion poems, we also offer a translation of that text, along with a version of Zhu Ziqing’s short essay on transience, to which Shuhe also refers.

We conclude with The Barren Tree 枯樹賦, a celebrated work of rhyming-prose by Yu Xin (庾信, 513–581 CE), translated and commented on by Stephen Owen. The last lines of Yu Xin’s composition echo the words 木猶如此,人何以堪, the key quotation in the text under discussion. The fate of trees and the meditation on human condition that it occasions leads us to recall The Use of the Useless, another chapter in The Tower of Reading.

***

During his tenure as the Communist Party Secretary of Zhejiang province from 2002 to 2006, Xi Jinping published a regular (possibly ghost-written) column in the local press under the title New Accounts of the Zhi River 之江新語. It was an obvious, albeit po-faced, reference to Liu Yiqing’s A New Account of the Tales of the World. That’s as far as the two works resembled each other: Xi’s articles were lugubrious and finger-wagging compositions aimed at educating wayward Party members and the unruly public. They adumbrated the teetotaler nature of his reign as Chairman of Everything, one that put paid to the latest quasi-Wei-Jin 魏晉 period in Chinese history when bon vivants and wits flourished for a time, as they had some seventeen centuries earlier.

***

I am grateful to Annie Ren 任路漫, a specialist in late-dynasty Chinese literature, who suggested translating some of Zhong Shuhe’s selections from New Tales of the World. Annie translated the material that lies at the heart of this chapter and kindly reviewed a number of drafts. Our thanks, as ever, to Callum Smith, the webmaster of China Heritage, for uploading high-resolution versions of the Chinese text of the ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion’, and to Duncan Campbell who granted us permission to reprint some of his work on the subject. (We also recommend the essay on the Orchid Pavilion, one of the forthcoming chapters in Intersections with Eternity, a ‘mini-anthology’ featured on the homepage of The Tower of Reading.) Our thanks also, as ever, to Reader #1 for going over the final draft of this chapter and pointing out a number of embarrassing errors. Those that remain are my responsibility alone.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

26 February 2024

***

Reference Material:

- 劉義慶著,世說新語,中國哲學書電子化計劃,full Chinese text

- Shih-shuo Hsin-yü: A New Account of Tales of the World, by Liu I Ch’ing, with commentary by Liu Chün, translated with introduction and notes by Richard B. Mather, 2nd ed., Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002

- Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, John Minford and Joseph M. Lau, eds, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000

- Geremie R. Barmé, Voices from the Bamboo Grove: The Humanity of Chinese Humour, 2 February 2012

- David Hawkes, The Age of Exuberance, in Classical, Modern and Humane, John Minford and Siu-kit Wong, eds, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1989, pp.306-308, reproduced with permission in China Heritage

- Stephen Owen, Deadwood: The Barren Tree from Yü Hsin to Han Yü, Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, vol.1, no.2 (July 1979): 157-179

And, by Annie Ren,

New Tales of the World

世說新語

If the stories, conversations, and short characterizations which make up this book of ‘Tales of the World’ describe an actual world, we might well ask what kind of world it is. Is it a real world or an imaginary one? Is it the whole world of its particular place and time (China in the second to fourth centuries) or only a narrow segment of that world? And finally, is it an objective portrayal of that world or a highly subjective tract pleading a special point of view? Questions such as these are surely not easily answered, if for no other reason than that the alternatives they pose are in most cases not mutually exclusive. …

The world of these tales is … a very narrow world indeed: of emperors and princes, courtiers, officials, generals, genteel hermits, and urbane monks. But though they live in a rarefied atmosphere of great refinement and sensitivity, they are, nevertheless, for the most part involved in a very earthly, and often bloody, world of war and factional intrigue. It is a dark world against which the occasional flashes of wit and insight shine the more brightly. …

But whatever other factors complicated the relations between these factions throughout this period — political, social, economic, or even religious — they seem to have boiled down by the third century to two fundamentally opposed points of view, which for convenience I shall designate by the terms most often used by contemporaries: those who favored naturalness ‘zìrán‘ [自然] versus those who insisted on conformity to the Moral Teaching ‘míngjiào‘ [明教]. In each succeeding period the issues were slightly different, but basically upholders of naturalness were inclined toward Taoism in their philosophy, unconventionality in their morals, and non-engagement in their politics, while upholders of conformity favored the Confucian tradition, fortified with a generous admixture of Legalism, conventionality in morals, and a definite commitment to public life. Though it is not blatantly obvious from a first reading of these tales, it is at least arguable that some characters appearing in them are more admirable than others. It is even possible to suggest that the admirable ones seem to hold certain characteristics in common. For example, they all seem to be lovers of good conversation and literature, they tend to prefer the regressive virtues of peace, tranquility, withdrawal, freedom, and unconventionality, and to despise aggressive qualities in the less admirable characters, such as martial prowess, virility, excitability, and rigid conformity to moral and ritual norms. In short the first group are adherents of naturalness and the latter of conformity, and whoever put these tales together seems to have had a preference for the former over the latter.

— from Richard B. Mather’s ‘Introduction’, Shih-shuo Hsin-yü, pp.xiii, xvi, xviii

***

A New Account of Tales of the World is a collection of anecdotes, bons mots and characterizations, mainly garnered from earlier written sources of the second through the fourth centuries and put together in the year 430 under the sponsorship of Liu Yiqing, Prince of Linchuan. The incidents described in it involve more than six hundred historical individuals who lived between the final years of Later Han and Liu’s own lifetime, but by far the largest number fall within the years immediately preceding dynasty of Eastern Jin (317-420).

Taken as a whole, Tales of the World has been loved by all educated Chinese ever since its first appearance in the fifth century. What appeals most to modern readers is the laconic but elegant prose style, a style that marks an early stage of greater expression in the history of Chinese literature. It goes beyond the extreme economy of classical and Han prose. Even though it is based on earlier documents, the style of Tales of the World is quite consistent and rather distinctive, using many more disyllabic expressions and expanding the number and subtlety of the function words. Since many of the episodes are conversations, including some so-called “pure conversation” debates, it seems reasonable to infer that the written style owes something to contemporary fourth- and fifth-century colloquial modes of expression. Another appealing feature is the delightful brand of humor, which even Westerners can appreciate.

Still another aspect of the work that makes it unique is the glimpse it gives of emerging values of the times — a sense of liberation from the oppressive constraints of the old Han Confucian orthodoxy. Values such as “cultivated tolerance” — the ability to maintain complete self-composure in the midst of danger and uncertainty, or total immunity from worldly cares and greed — are illustrated in the case of Ruan Fu and his love of wooden clogs, released from the wracking anxiety that continually plagued the miser, Zu Yue. The new stress on “freedom and nonrestraint”, which produced a sort of cult of individuality and eccentricity, is dramatically illustrated by the bibulous exploits of Liu Ling, a member of the reclusive coterie, the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. Following the lead of this group a generation later were the Eight Free Spirits, who carried their liberated lifestyle to even greater extremeness. Still later, Wang Xianzhi, the talented son of the calligrapher Wang Xizhi, acting on a completely spontaneous impulse, travelled all night in a small boat to see a friend. But when he reached the friend’s gate he turned back without seeing him, because, as he explained, “the impulse was spent” [乘興而行,興盡而返].

Other values that surface in this work include a greater sensitivity toward the plight of women and the infiltration of Buddhist ideas into the intellectual and religious climate of the times. The somewhat rarefied, and at least partially fictionalized “world” that these “tales of the world” portray — confined as it is to emperors, generals, genteel hermits, and urbane monks — is nonetheless the real world of the exiled aristocrats who had fled the barbarian conquest of their homeland in the north at the beginning of the fourth century and were now losing ground to rising families of the south. In these tales we get a momentary glimpse of their daily lives, a tiny glimmer of what they must have felt and thought in the face of the ever-present threat of extinction.

— Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Columbia University Press, 2000, p.665

***

The period of four centuries from the decline of the Han dynasty to the formation of the aristocratic Sui and Tang empires was one of the richest and most complex in the intellectual history of the Chinese world. It was astonishingly fertile and abounded in innovations. It witnessed the development of a metaphysics completely free of the scholasticism of the Han age and enriched from the beginning of the fourth century by the Buddhist contribution of the Great Vehicle, the doctrine of the universal void. It also witnessed the affirmation of a sort of artistic and literary dilettantism, a pursuit of aesthetic pleasure for its own sake which was in complete contradiction with the classical tradition; it witnessed the first, remarkable attempts at literary and artistic criticism; the promotion of painting from the rank of craft to that of a skilled art, rich in intellectual content; the first appearance in world history of landscape as a subject for painting and as an artistic creation; and an unprecedented efflorescence of poetry. …

The metaphysical movement (the revival of Taoist speculation) expressed itself, in the world of the literati, in nonconformist attitudes — contempt for rites, free and easy behavior, indifference to political life, a taste for spontaneity, love of nature. Independence and freedom of mind, a horror of conventions, a passion for art for art’s sake are characteristic of the whole troubled age from the third to the sixth century. It would be legitimate to say that a sort of “aestheticism” was dominant throughout the Chinese Middle Ages. The first figures to show signs of these tendencies, which were so clearly opposed to the classical tradition, were the ones who were to be christened the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, a little group of Bohemian literati, the best known of whom is the poet and musician Xi Kang [嵇康]. The same attitudes of mind, the same taste for nature and freedom persisted in aristocratic circles after the exodus to the valley of the Yangtze. We find them in the group headed by the famous poet and calligrapher Wang Xizhi, with whose name is connected one of the most famous episodes in the history of Chinese literature and calligraphy, the Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion at Kuaiji (in the neighborhood of present-day Shaoxing in Zhejiang), where, after many a libation, forty-one poets [sic] competed at improvising poems.

— Jacques Gernet, quoted in Classical Chinese Literature, p.444

***

‘If this is what becomes of trees …’

木猶如此,人何以堪。

When passing by Jincheng [in modern-day Jiangsu] during his northern expedition [in the year 369 CE], Huan Wen noticed the willows that he had planted when he was in charge of Langya [in 314) had grown to a girth of many arm spans.

“If this is what becomes of trees,” he commented wistfully, “how can we bear our own fate?”

[Or, “If this be the fate of these trees, how can anyone cope?” Alternatively, “Surely our own state doesn’t bear thinking about, if even trees age thus.”]

Pulling a branch towards him, Huan’s tears flowed as he broke off a switch.

— ‘Chatter and Gossip, 55’, New Tales of the World, modified by Annie Ren with Geremie R. Barmé on the basis of Richard Mather’s translation

桓公北征經金城。見前為琅琊時種柳。皆已十圍。慨然曰:木猶如此,人何以堪。攀枝折條,泫然流淚。

— 劉義慶著《世说新语·言語》, 55

A Comment from The Tower of Reading

永恆的悲哀

Life is brief and time fleeting — such are the melancholic realities of our condition; we mourn the ephemeral. Such sentiments are found both in Wang Xizhi’s ‘Preface to the Collected Poems of the Orchid Pavilion’ and in ‘Fleeting Time’, an essay by Zhu Ziqing. After all, most people are, as Wang Xizhi famously observed, ‘distracted by evanescent things’. Like mayflies flitting around in the sunlight, people are for the most part completely oblivious to the short span of their existence.

Notes:

- Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303-361 CE) is famed as a calligrapher and for his ‘Preface to the Collected Poems of Orchid Pavilion’ 蘭亭集序, the full text of which is given below. See also Spring Lustration 脩禊 — a pavilion, a calligrapher and eternity, China Heritage, 29 March 2017.

- Zhu Ziqing (朱自清, 1898-1948) was a prominent modern essayist. For a translation of ‘Transience’ 匆匆, see below.

- The words ‘distracted by evanescent things’ 欣於所遇 are quoted from Wang Xizhi’s ‘Preface’. H.C. Chang translates the line 當其欣於所遇,蹔得於己,怏然自足,不知老之將至 as ‘When absorbed by what they are engaged in, they are for the moment content, and in their content they forget that old age is at hand.’

According to the history books, Huan Wen [桓溫, 312-373] was a rebel, yet only ‘second-rate when compared to the likes of Sun Quan [孫權, 182-252, founder of the Eastern Wu dynasty during the Three Kingdoms period] and Sima Yi [司馬懿, 179-251, regent and effective ruler of the Wei dynasty also during the Three Kingdoms period]’. Nonetheless, Huan was a man whose talent was well suited to his ambition. By the age of twenty-three he was in charge of the Langya Commandery, but for someone so young that early success merely served to whet his appetite for greater things, and frustrations. Thereafter, however, he encountered few substantial setbacks and rose steadily through the ranks at the court of the Eastern Jin dynasty.

Note:

- In his introduction to New Tales of the World, Mather describes Huan Wen as a ‘vigorous military activist, full of patriotic and moral platitudes’ (p.xxiii). His personality is in contrast to that of Xie An (謝安, 320-385), who figures in over a hundred anecdotes. Xie’s prowess in “pure conversation” 清談 qīngtán was acknowledged even by his enemies, and, characteristically, he remained a recluse in the Zhejiang hills until he was forty before finally answering the desperate need of the realm for his talents. He faced many grave crises in the course of his rise to supreme power at court, but always with total tranquillity, a quality named “cultivated tolerance” 雅量 yǎ liàng in the “Tales,” which devotes an entire chapter to examples of its exercise. Cultivated tolerance includes the ability to conceal the slightest hint of anxiety, fear, excitement, or joy in either facial, verbal, or bodily expression. It is very much like the quality of “imperturbability” (ataraxia) so highly prized in the late Hellenistic world, another highly civilized society living under the imminent threat of extinction. In Xie An’s case, whether he was caught in a sudden squall on a boating excursion, or facing ambush and certain death at a banquet served by his mortal enemy, or receiving the victory announcement of the Eastern Chin forces over vastly superior odds at the Fei River, in each situation he simply went on chanting poems or playing encirclement chess as if nothing had happened. More aggressive men, by contrast, are certainly held up to no great honor in the “Tales.” Beside Huan Wen (312-373), the military dictator and near usurper who serves as the perfect foil for Xie An, there is the bold adventurer Wang Dun (266-324). … Xie An’s imperturbability is emphasized by Huan Wen’s irascibility…’ (Mather, pp.xviii-xix) For a modern example of a clash over ‘cultivated tolerance’ 雅量 yǎ liàng, see the case of Mao Zedong and Liang Shuming, see the section ‘Notes by China Heritage‘ in ‘That which cannot be taken away’, an earlier chapter in The Tower of Reading.

By the time he embarked on his northern expedition in the year 369 Huan Wen had, as Yu Jiaxi observes in his annotations to New Tales of the World, reached the pinnacle of his career. Since by then he dominated both the military affairs of the dynasty and the court itself, it seemed possible that he might have usurped the throne. Yet, as Liu Pansui wrote, ‘by then Huan Wen was already an old man of sixty’, observing that ‘grey hair is the great equaliser in life’. So, although the general may well have been at the height of his powers, he also knew that it was not in his lot to occupy the throne.

- 余嘉錫《世說新語箋疏》, in which he quotes the words of Liu Pansui (劉盼遂, 1896-1966).

When Huan Wen saw those trees he had planted long ago, the north-quelling general revealed his true self, acknowledging that he was a normal mortal, just like everyone else.

— Zhong Shuhe, trans. Annie Ren

***

Source:

- Chapter One in Section Fourteen of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading 《念樓學短·世說新語之一》,長沙:岳麓書社,2022年,上冊,第298-299頁。

Chinese Text

學其短:The selected Classical Chinese text, with notes;

念樓讀:Zhong Shuhe’s translation into Modern Chinese; and,

念樓曰:Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive comment on the text.

永恆的悲哀

桓公北征經金城。見前為琅琊時種柳。皆已十圍。慨然曰:木猶如此,人何以堪。攀枝折條,泫然流淚。

【学其短】

- 本文錄自《世說新語·言語》。《世說新語》是雜記漢末魏晉人物言行的一部書,劉義慶撰。

- 劉義慶,南朝彭城人,宋武帝劉裕之侄,襲封臨川王。

- 桓公,桓溫,東晉權臣,明帝的女婿。

- 琅琊,郡名,治地在今山東諸城。晉室南渡後在金城(今江蘇句容)僑置。

【念樓讀】桓溫為大司馬,領平北將軍,統兵北伐。行經金城,見到自己從前任琅琊太守時移栽在此地的楊柳,已經長成合抱的大樹,他很有感觸,深情地說:“樹都長得這麼大了,教人怎麼能不老。” 一面攀挽著低亞的柳條,輕輕地撫摸著,眼淚奪眶而出。

【念樓曰】生命有限而流年易逝,這是人類普遍的永恆的悲哀。王羲之《蘭亭集序》和朱自清《匆匆》寫的便是它。不過常人“欣於所遇” 時,就像飛舞在陽光中忙著找物件的蜉蝣,不會感覺到這一點。

桓溫在史書上被稱叛逆,說他是“孫仲謀、晉宣王(司馬懿)之流亞”,反正是一個野心大本事也大的人。他二十三歲就當了琅邪(治金城)太守,可謂少年得志,後來在東晉朝廷中的地位步步上升,少有蹉跌。此次北伐,余嘉錫《世說新語箋疏》說在太和四年,桓溫的權力已臻頂峰,總統兵權,專擅朝政,到了可以廢立皇帝的程度。然而“公道世間惟白髮”,“溫時已成六十之叟”(《世說新語箋疏》引劉盼遂語),大概覺得縱然人生得意,仍然“大命未集”(同上)。

這時候,大司馬領平北將軍也就現了原形,仍然是一個普通而真實的人。

***

Source:

- 鐘叔河著,《念樓學短·世說新語之一》,上冊,第298-299頁。

***

Eternity in the Orchid Pavilion

‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection’

Wang Xizhi

Translated by H.C. Chang

During the late spring of the Ninth Year of the Everlasting Harmony 永和 reign period of the Eastern Jin dynasty (353 CE), Wang Xizhi gathered forty-one of his friends and relatives (including his son, Wang Xianzhi (王獻之, 344-388) in order to undertake the Spring Lustration Ceremony, one whereby the evil vapours of the winter past were washed away in the eastward flowing waters. Twenty-six of the men named as being present produced between them a total of thirty-seven poems, and towards the end of the day, we are told, Wang Xizhi, formerly employed in the Imperial Library but then serving in Guiji as the General of the Army on the Right 右軍, wrote his immortal preface to this collection, on ‘cocoon paper’ with a ‘weasel-whisker brush’, in 324 characters and 28 columns.

— Duncan Campbell, Literary Representations of the Orchid Pavilion

***

To the poems Wang Xizhi contributed a famous preface. His own calligraphy of that preface is perhaps the single best-known work of Chinese calligraphy (controversy has always surrounded the authenticity of the various surviving copies). It is a magnificent document in the history of Chinese sensibility. For it is the first considered statement on the application of Zhuangzi’s doctrine of consonance with the cosmic principle to the contemplation of hills and streams and, summarizing as it does the outlook of several centuries, is a lasting part of the Chinese heritage. In the poems and in the preface itself, man’s gaze is directed with childlike wonder to the world he inhabits. The eye does not rest on flower or tree or hill or brook as in earlier verse and in the Book of Songs, but roves over them all in a sweeping survey. Not content with the delight this affords, the mind reaches out to the empyrean and beyond. What is more, man’s cherished feelings not only find release but positively seek fulfillment in the natural world. The mountain heights, the sheer cliffs, the cascading waterfall, the echoing valley, the ever-widening horizon — these mirror the inner world; aspiration is assuaged by height; magnanimity comes into its own with spaciousness; solitude finds a ready harbor in the woods.

— H.C. Chang

***

In the ninth year [353] of the Yonghe [Everlasting Harmony] reign, which was a guichou year, early in the final month of spring, we gathered at Orchid Pavilion in Shanyin in Guiji for the ceremony of purification. Young and old congregated, and there was a throng of men of distinction.

Surrounding the pavilion were high hills with lofty peaks, luxuriant woods and tall bamboos. There was, moreover, a swirling, splashing stream, wonderfully clear, which curved round it like a ribbon, so that we seated ourselves along it in a drinking game, in which cups of wine were set afloat and drifted to those who sat downstream. The occasion was not heightened by the presence of musicians. Nevertheless, what with drinking and the composing of verses, we conversed in whole-hearted freedom, entering fully into one another’s feelings. The day was fine, the air clear, and a gentle breeze regaled us, so that on looking up we responded to the vastness of the universe, and on bending down were struck by the manifold riches of the earth. And as our eyes wandered from object to object, so our hearts, too, rambled with them. Indeed, for the eye as well as the ear, it was pure delight! What perfect bliss! For in men’s associations with one another in their journey through life, some draw upon their inner resources and find satisfaction in a closeted conversation with a friend, but others, led by their inclinations, abandon themselves without constraint to diverse interests and pursuits, oblivious of their physical existence. Their choice may be infinitely varied even as their temperament will range from the serene to the irascible. Yet, when absorbed by what they are engaged in, they are for the moment pleased with themselves and, in their self-satisfaction, forget that old age is at hand. But when eventually they tire of what had so engrossed them, their feelings will have altered with their circumstances; and, of a sudden, complacency gives way to regret. What previously had gratified them is now a thing of the past, which itself is cause for lament. Besides, although the span of men’s lives may be longer or shorter, all must end in death. And, as has been said by the ancients, birth and death are momentous events. What an agonizing thought! In reading the compositions of earlier men, I have tried to trace the causes of their melancholy, which too often are the same as those that affect myself. And I have then confronted the book with a deep sigh, without, however, being able to reconcile myself to it all. But this much I do know: it is idle to pretend that life and death are equal states, and foolish to claim that a youth cut off in his prime has led the protracted life of a centenarian. For men of a later age will look upon our time as we look upon earlier ages—a chastening reflection. And so I have listed those present on this occasion and transcribed their verses. Even when circumstances have changed and men inhabit a different world, it will still be the same causes that induce the mood of melancholy attendant on poetical composition. Perhaps some reader of the future will be moved by the sentiments expressed in this preface.

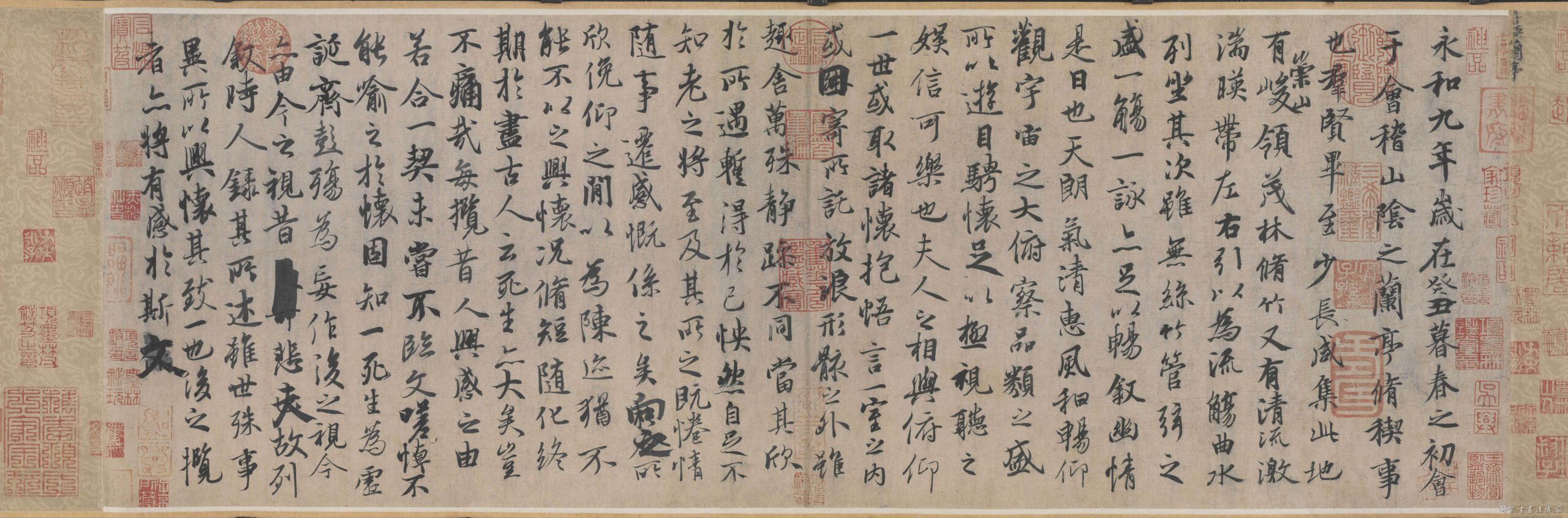

蘭亭集序

王羲之

永和九年,歲在癸丑,暮春之初,會于會稽山陰之蘭亭,脩褉事也。群賢畢至,少長咸集。此地有崇山峻嶺,茂林脩竹,又有清流激湍,映帶左右,引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次。雖無絲竹管絃之盛,一觴一詠,亦足以暢敘幽情。

是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢,仰觀宇宙之大,府察品類之盛,所以遊日騁懷,足以極視聽之娛,信可樂也。

夫人之相與,俯仰一世,或取諸懷抱,悟言一室之內,或因寄所託,放浪形骸之外。雖趣舍萬殊,靜躁不角,當其欣於所遇,暫得於己,快然自足,不知老之將至。及其所之既惓,情隨事遷,感慨係之矣。向之所欣,俛仰之間,已為陳。猶不能不以之興懷。況脩短隨化,終期於盡。古人云,死生亦大矣,豈不痛哉。

每覽昔人興感之由,若合一契,未嘗不臨文嗟悼,不能喻之於懷。固知一死生為虛誕,齊彭殤為妄作,後之視今,亦猶今之視昔,悲夫。故列敘時人,錄其所述,雖世殊事異,所以興懷,其致一也。後之儿覽者,亦將有感於斯文。

***

Source:

- H.C. Chang, trans., Chinese Literature: Volume Two: Nature Poetry, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1977, pp.8-9 (romanisation altered, translations of the reign title and pavilion name added). Quoted by Duncan M. Campbell in The Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations, China Heritage reprint

***

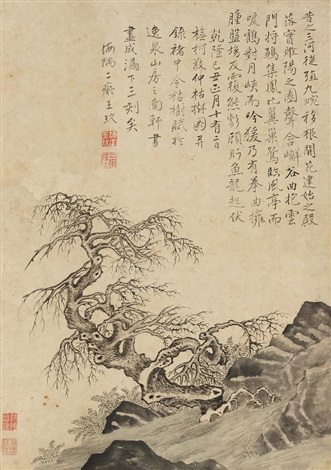

‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems’ in Calligraphy

For a high-definition image of the Feng Chengsu’s Shenlong Version 馮承素神龍本 of Wang Xizhi’s ‘Preface’, click on the image below (to be read/ scrolled from right to left):

This is the most renowned, and widely reproduced, copy of Wang Xizhi’s original text. Dating from the Tang dynasty, it was long held in the former imperial collection, part of which is now stored in the Beijing Palace Museum. (This copy of the ‘Preface’ is called the Shenlong Version because it carries a seal with the reign title Shenlong on it. The Shenlong 神龍 reign was from 705 to 707 CE.)

Alternatively, click on the following image to see the stand-alone text of Wang’s ‘Preface’ from the Shenlong scroll:

***

Source:

- Spring Lustration 脩禊 — a pavilion, a calligrapher and eternity, China Heritage, 29 March 2017

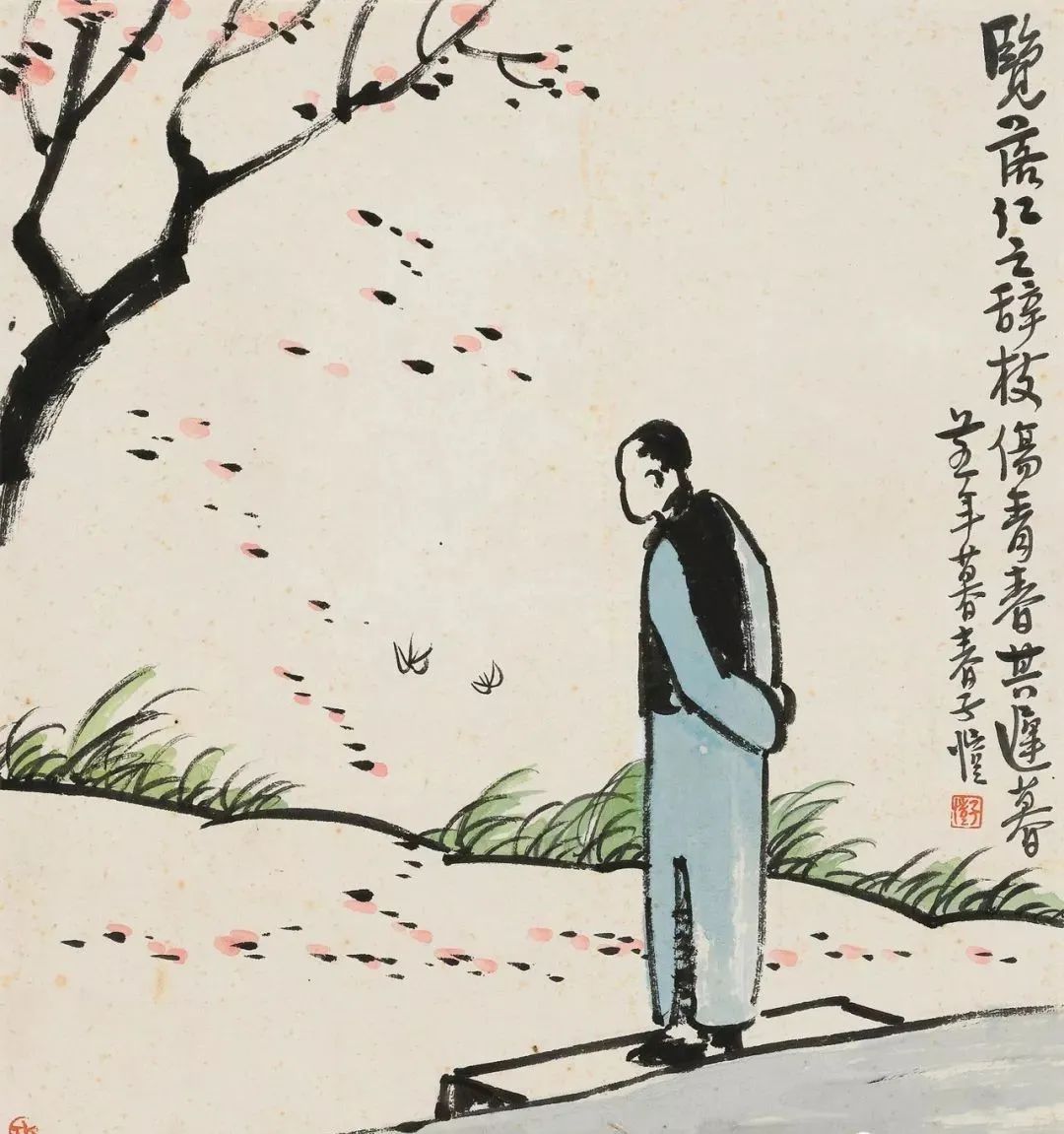

Fleeting Time

Zhu Ziqing

The swallows may have gone, but they will return in due course, just as the willow trees denuded of foliage for the moment will sprout anew, and the peach blossoms will bloom again. But, Clever One, tell me now, why do our days pass by never to come back? Does someone steal them away and, if so, who could that possibly be? Or are they hidden away somewhere? If they have fled of their own accord where are they, pray tell?

I’m not sure how many days are my lot, though I do know that they are constantly being depleted. According to my silent calculation I realise that over 8000 days have already slipped through my fingers. Like a pin-prick-sized drop of water in the ocean, my days disappear drop by tiny drop in the great confluence of time. Silently they pass without leaving a hint of their existence. The sound of that relentless drip resounds in my head as my tears well up and melt into the confluence.

What has passed is beyond recall; whatever may come will inevitably come. Yet why are things so fleeting, between that going and the coming?

A shaft of sunlight streams into my wretched room when I wake in the morning and the light, like footsteps, travers the day in silence, while I follow that diurnal rhythm in an inevitable daze. Time passes like the water that streams away whenever I wash my hands. The days disappear just like each bowl of rice that I eat. When I’m sitting silently by myself, in the corner of my eye I sense time stealthily passing by. I sense its fleeting passage and, whenever I stretch out a hand to stall its progress, it slips away, beyond my grasp. When I’m in bed at night, time steps over me with agility, fleeing from my feet. Upon waking, when I see the sunlight again, I realise that yet another day has passed. I sigh, holding my face in my hands, but the shadow of the new day is already passing me by.

As the days fly by, what can I do but live on in this world of multitudes? I can but wander, hesitate and join in the fleeting moment myself. In the 8000 days that have already departed, apart from my lingering present, what remains? The past is like a wisp of smoke, the slightest breeze scatters it; it’s like a mist that dissolves in the morning light. What remains of me? Does anything survive at all, even a feeble trace? I came into this world naked and, in the batting of an eye, I will leave it, naked still. But a question unsettles me: why am I here at all?

Now you tell me, Clever One, why do our days pass like this, never to return?

28 March 1922

— trans. G.R. Barmé

***

***

匆匆

朱自清

燕子去了,有再来的时候;杨柳枯了,有再青的时候;桃花谢了,有再开的时候。但是,聪明的,你告诉我,我们的日子为什么一去不复返呢?——是有人偷了他们罢:那是谁?又藏在何处呢?是他们自己逃走了罢:现在又到了哪里呢?

我不知道他们给了我多少日子;但我的手确乎是渐渐空虚了。在默默里算着,八千多日子已经从我手中溜去;像针尖上一滴水滴在大海里,我的日子滴在时间的流里,没有声音,也没有影子。我不禁头涔涔而泪潸潸了。

去的尽管去了,来的尽管来着;去来的中间,又怎样地匆匆呢?早上我起来的时候,小屋里射进两三方斜斜的太阳。太阳他有脚啊,轻轻悄悄地挪移了;我也茫茫然跟着旋转。于是——洗手的时候,日子从水盆里过去;吃饭的时候,日子从饭碗里过去;默默时,便从凝然的双眼前过去。我觉察他去的匆匆了,伸出手遮挽时,他又从遮挽着的手边过去,天黑时,我躺在床上,他便伶伶俐俐地从我身上跨过,从我脚边飞去了。等我睁开眼和太阳再见,这算又溜走了一日。我掩着面叹息。但是新来的日子的影儿又开始在叹息里闪过了。

在逃去如飞的日子里,在千门万户的世界里的我能做些什么呢?只有徘徊罢了,只有匆匆罢了;在八千多日的匆匆里,除徘徊外,又剩些什么呢?过去的日子如轻烟,被微风吹散了,如薄雾,被初阳蒸融了;我留着些什么痕迹呢?我何曾留着像游丝样的痕迹呢?我赤裸裸来到这世界,转眼间也将赤裸裸的回去罢?但不能平的,为什么偏要白白走这一遭啊?

你聪明的,告诉我,我们的日子为什么一去不复返呢?

1922年3月28日

***

Source:

- 朱自清,匆匆,新華網

The Barren Tree of Yu Xin

枯樹賦

Yu Xin 庾信

Translated by Stephen Owen

‘This tree is withering away: the life in it is gone.’

此樹婆娑,生意盡矣。

The 賦 fù, ‘rhapsody’ or ‘rhyme-prose’, was a highly ornate literary form that flourished in the Han and Six Dynasties period. In The Age of Exuberance, David Hawkes writes:

The long, ornate, rhapsodic fu, in so far as it had an ancestor, derived from the shaman-chants of the South. Its lexical richness, euphuism and hyperbole suited an expansive, adventurous age in which Chinese armies penetrated deep into Central Asia and Chinese merchandise regularly found its way into European markets, but were deeply disturbing to right-minded Confucians, and therefore, ultimately, to the writers themselves; so that, amidst all the self-confident exuberance, a note of guilt and unease kept stealing in. …

Later attitudes to the literary achievements of this age were somewhat ambivalent. It’s gongoristic, allusive, overwrought prose went out of fashion, and its poetry, particularly the ‘Palace Style’ favoured by Xiao Gang, came to be regarded as artificial, trivial and ‘decadent’. Yet poets of this period were admired by Du Fu and Li Bo, and all Tang poets were to some extent formally indebted to them.

Yu Xin’s ‘The Barren Tree’ 枯樹賦 is famous in its own right and for casting the stories of Yin Zhongwen and Huan Wen in the rhapsodic form.

Mao Zedong, a poet of uneven accomplishment, returned to Yu Xin’s rhapsody and is said to have intoned lines from it in the shadow of his own demise. Popular accounts of his life claim that, upon hearing of the death of his son Mao Anying in 1950, the chairman stared at the trees in the courtyard of his palace residence in Zhongnanhai and chanted:

‘If this is what becomes of trees, how can we bear our own fate?’

[Note: See also: 現炒冷飯 — Chef Wang Makes a Hash of Egg-fried Rice, 1 November 2023.]

Just as Huan Wen, described by Mather in the above as a ‘vigorous military activist, full of patriotic and moral platitudes’ tearfully confronted his mortality, so Mao Zedong, a military leader of another age, returned to Yu Xin’s barren tree and the nature of human frailty.

Here we reproduce Stephen Owen’s highly wrought elliptically annotated translation of Yu Xin’s rhapsody followed by an excerpt from his commentary on ‘barren trees’.

For more on the rhyme-prose of the 賦 fù, see ‘Red and Purple Threads: Rhapsodies from the Han and Six Dynasties’, chapter six in Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, pp.267-327.

— GRB

Yin Zhongwen was a free spirit and a man of learning, whose fame was known the whole world over.

When the times changed, he went forth to serve as Governor of Dongyang.

But always he was unhappy and ill at ease. He gazed at the locust tree in the courtyard and, sighing, he said:

‘This tree is withering away: the life in it is gone.’

殷仲文風流儒雅,海內知名。

世異時移,出為東陽太守。

常忽忽不樂,顧庭槐而歎曰:

此樹婆娑,生意盡矣。…

Trees like the pure pines in White Deer Pass or the striped zi tree that became a grey ox—their roots may hump and coil around the folds of a mountain slope; but why does the cassia waste away and perish [as Han Wudi lamented when he lost Lady Li], why then is the wutong half dead [as described in the Qifa]?

Once transplanting succeeded in the Three River Provinces [when the altar tree of the house of Han flourished again for Guangwudi, Liu Bei of the Shu-Han Kingdom, and Liu Yu of the Song]; and roots were shifted in the nine acres [as in the Li Sao]. Such trees blossomed by [Cao Cao’s] Jianshi Palace, and their fruits fell in the gardens of Suiyang [of Prince Xiao of Liang]. Within them lay the music of Xie Valley [where the Yellow Emperor sent his musician Li Ling to get bamboo for pipes]; and of song they contain the “Gates of Cloud” [of the Yellow Emperor].

These trees are roosts for the “phoenix with its brood” [song title], and provide nests for the pair of ducks that share a single wing [showing their conjugal devotion]. When they hang over wind-swept pavilions, the cranes cry out; when they face moonlit gorges, they bring gibbons to moan.

至如白鹿貞松,青牛文梓,根柢盤魄,山崖表裡。桂何事而銷亡,桐何為而半死?昔之三河徙植,九畹移根。開花建始之殿,落實睢陽之園。聲含嶰谷,曲抱《雲門》。將雛集鳳,比翼巢鴛。臨風亭而唳鶴,對月峽而吟猿。

Then there are those which are gnarled, knotty, pocked, inverted, where bears and tigers turn heads and look, where fish and dragons rise and sink, upright, knobbed like capitals, mountain-linked; cross-grained and crinkling like waters.

[Zhuangzi’s] Carver Shi is startled to see such as these; the craftsman Gongshu Ban’s eyes are dazzled. First the carving out is done; then curved awls and scrollers are applied.

They level scales and scrape shells flat, fell horns and break off tusks, layer after layer of shattered brocade, petal after petal of true flowers, grass and trees spreading in profusion, mists and red clouds scattering in confusion.

乃有拳曲擁腫,盤坳反覆,熊彪顧盼,魚龍起伏。節豎山連,文橫水蹙,匠石驚視,公輸眩目。雕鐫始就,剞劂仍加;平鱗鏟甲,落角摧牙;重重碎錦,片片真花;紛披草樹,散亂煙霞。

Then there are trees like the pine, pomegranate, ginko, and persimmon [mentioned together in Zuo Si’s ‘Fu on the Capital of Wu’] whose dense tops spread over a hundred acres, and sprouts from whose stumps last a thousand years.

In Qin one of these was appointed as a minister [when Qin Shihuang enfeoffed a tree that sheltered him from a storm], and in Han a general sat under one [Fen Yi, the “General of the Big Tree”].

But they all become buried in moss, weighed down by growths, pared by the birds, bored into by worms, and some hang low with the frost and dew, some are shaken and ruined by winds and mist.

East by the sea was a temple for a white tree, and an altar for a barren mulberry lay in the western reaches of the Yellow River; and in the northland they made a gate of willow leaves, and at South Ridge made a foundry among plum roots; in Xiaoshan [‘s poem, “the Summons to the Recluse,” in the Chuci] groves of cassia could make one linger, while in the “Ballad of Fufeng” Liu K’un tied his horse to a tall pine do you think such famous trees are found only where the walls [of Chang’an] look down on Thinwillow Camp, or where the passes sink behind Peach Forest [in the capital region]?

若夫松子、古度、平仲、君遷,森梢百頃,槎枿千年。秦則大夫受職,漢則將軍坐焉。莫不苔埋菌壓,鳥剝蟲穿。或低垂於霜露,或撼頓於風煙。東海有白木之廟,西河有枯桑之社,北陸以楊葉為關,南陵以梅根作冶。小山則叢桂留人,扶風則長松繫馬。豈獨城臨細柳之上,塞落桃林之下?

But when they are separated [from their native soil] by mountains and rivers, or are leaf-stripped in parting, their torn up roots may cause tears to be shed, or their wounded radicals may ooze blood; fire will enter their hollow trunks [pun: “hearts”], and sap flow from their broken joints [pun: “resolution”]. They lie slanting, stretched across the mouths of caves; or are broken in half, collapsed across the waists of mountains. Those of slanting stripes ice-shatter their hundred-span girths; the straight-grained tile-split their thousand yard heights.

Knob-covered, filled with swellings, pierced in hidden places, holes within, there tree goblins flicker, and mountain demons cast their spells.

若乃山河阻絕,飄零離別。拔本垂淚,傷根瀝血;火入空心,膏流斷節。橫洞口而欹臥,頓山腰而半折。文斜者百圍冰碎,理正者千尋瓦裂。戴癭銜瘤,藏穿抱穴;木魅賜睒,山精妖孽。

Worse still that the winds and thunder no longer stir them, and that their onetime lodgers never return

No more can one ‘gather dolichos’ there [interpreted to mean that even while one is away a short while ‘gathering dolichos,’ one is slandered in court; i.e. Yin Zhongwen and I need not worry about our reputations at home ‘because we’re not returning]; but one can still eat the bracken [as did Boyi and Shuqi, the loyal recluses who refused to serve a usurping state].

They lie sunken away in some narrow lane or drowned in weeds by a thatch door.

Once I was pained by the falling of leaves from such trees; now I sigh even more for their dying.

The Huainanzi says: ‘When leaves fall from the trees, old men grieve.’ This is what I am talking about.

況復風雲不感,羈旅無歸,未能采葛,還成食薇。沉淪窮巷,蕪沒荊扉。既傷搖落,復嗟變衰。《淮南子》云:木葉落,長年悲。斯之謂矣。

Hence my song:

“They are the fire that lasted three months at Jianzhang Palace, they are the log going thousands of miles on the Yellow River: they might have been the trees that once filled [Shi Chong’s] garden of Golden Valley — and if not, then surely they were a whole county of blossomers in Heyang [the peach trees planted by Pan Yue].”

The Grand Marshal, Huan Wen, heard of this and sighed, saying:

“Once a long time ago I planted willows, and Hannan swayed with their pliant branches; now I see them as they lose their leaves, and the pools of the Yangtze become a sad sight.

If it is so even with trees, how can one bear if thinking of man?”

乃歌曰:建章三月火,黃河萬里槎。若非金谷滿園樹,即是河陽一縣花。

桓大司馬聞而歎曰:昔年種柳,依依漢南;今看搖落,淒愴江潭。

樹猶如此,人何以堪。

***

Source:

- Stephen Owen, Deadwood: The Barren Tree from Yü Hsin to Han Yü,Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, vol.1, no.2 (July 1979): 157-179, at pp.157-159

***

***

On the Barren Tree

As if to justify the novelty of the barren tree ku shu 枯樹[1] as a topic for a yongwu fu 詠物賦 (fu on a “thing”), Yu Xin frames his work with perhaps the most famous story of a barren tree, Yin Zhongwen’s sigh over the “locust tree in the courtyard” 庭槐. In the original anecdote, the locust tree was not only a sign of the impermanence of things, it was also an emblem of political failure, a reference to Yin’s own waning fortunes or to those of the Jin strongman Huan Xuan (桓玄, 369-404), who had recently been defeated by Liu Yu 劉裕, the founder of the Liu-Song Dynasty. Writing this fu during his captivity in the north, Yu Xin clearly intended that the political associations of the barren tree be present, but the closing citation from the Huainanzi and the anecdote about Huan Wen indicate that the more general associations of impermanence had not disappeared. Through the strong topical associations in both the Yin Zhongwen anecdote and the fu of Yu Xin, the barren tree came to be treated as topical allegory, and it retained this convention of use at least through the eighth century.

In his fu Yu Xin synthesized elements from a vast body of tree lore. The trees of the Yin Zhongwen and Huan Wen anecdotes ultimately derive from the commonplace image of the autumn tree, a favorite marker of impermanence in the poetry of the second and third centuries and usually traced back to the Jiupian 九篇 of the Chuci 楚辭. A second source of associations developed out of the play on words between “timber” 材 and “talent” 才. This felicitous pun generated a whole family of conventional metaphors; e.g. the man of talent/timber may serve as a “beam” in the edifice of the state; raw talent/timber may be “carved” and given the adornment of culture or may prove too “rotten to decorate. And early Taoist writers could not resist evolving their own counter-metaphors in the gnarled tree, which by its seclusion or deformity manages to preserve its natural state and avoid the craftsman’s axe. A third and independent set of associations lies in portent lore, where seemingly lifeless trees flower out of their barrenness to indicate the restoration of a clan or dynasty.[3] …

… The barren tree is clearly an emblem of Yu Xin himself, transplanted from his native soil and wasting away in the North. Following old fu tradition in framing his poem with a historical anecdote, Yu Xin delivers it through the mouth of Yin Zhongwen, subsequent to his famous exclamation about “locust tree in the courtyard.” However, Yu’s exposition of the topic is both simple and untraditional: instead of an orderly presentation of various aspects of the topic, the poet moves through a series of strophes each giving examples of trees in the glory trees in decline. Finally when the theme of transplanting occurs — the situation most analogous to Yin Zhongwen’s situation and his own — Yu lingers to describe the pathos of the ruined tree.

… The force of the tradition would not allow the question of the barren tree’s usefulness to be avoided very long. Every reader knew the elaboration of the timber/talent pun in Analects V.ix.I:

“Zai Yu was sleeping during the day, and the Master said, ‘Rotten wood cannot be carved …’ ”[4]

If there is dead wood, there may be rotten wood: the person who identifies himself with the barren tree may prove to be of no use to the state (fortunately or unfortunately, according to his philosophical inclinations). Sun Wanshou adds this inevitable element to the topic: no carver need look at the barren tree because it is worthless. Only an occasional context for the poem would indicate if this is a blessing or a curse.

Notes:

- Ku 枯 (translated as “barren”) is a difficult term with no exact equivalent in English. It refers to the apparent lifelessness of trees and vegetation in winter or to the real lifelessness of dead trees and vegetation. It describes appearance, implying “witheredness” (applicable to non-woody vegetation, leaves, human appearance in old age or sickness), “dryness” (with general application), and “leaflessness” (applied to trees”). “Barren” is an uneasy compromise implying leaflessness and retaining ku’s appearance of death without necessarily implying true death; i.e. both a winter tree and a dead tree may be said to be “barren.” [Stephen Owen]

- This well-known story of Yin Zhongwen (d. 407) can be found in Jin shu, 99, and in the Shishuo xinyu 3B.306, translated by Richard Mather, A New Account of Tales of the World by Liu I-ch’ing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976) p.453. [Stephen Owen]

- China Heritage note: See The Use of the Useless in The Tower of Reading.

- China Heritage note: Zai Yu was sleeping during the day. The Master said: “Rotten wood cannot be carved; dung walls cannot be troweled. What is the use of scolding him?” The Master said: “There was a time when I used to listen to what people said and trusted that they would act accordingly, but now I listen to what they say and watch what they do. It is Zai Yu who made me change.”

宰予晝寢,子曰:朽木不可雕也,糞土之牆不可圬也。於予與何誅。

子曰:始吾於人也,聽其言而信其行;今吾於人也,

聽其言而觀其行。於予與改是。— Analects 5.10,《論語·公冶長》, trans. Simon Leys,

quoted in The Use of the Useless

***

Source:

- Stephen Owen, Deadwood, pp.157-172, with minor changes and additions

***