The Tower of Reading

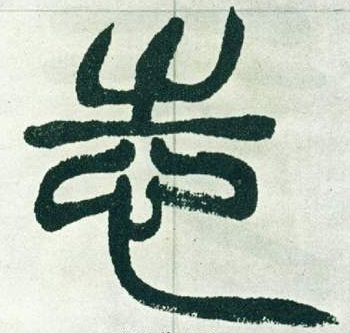

不可奪志

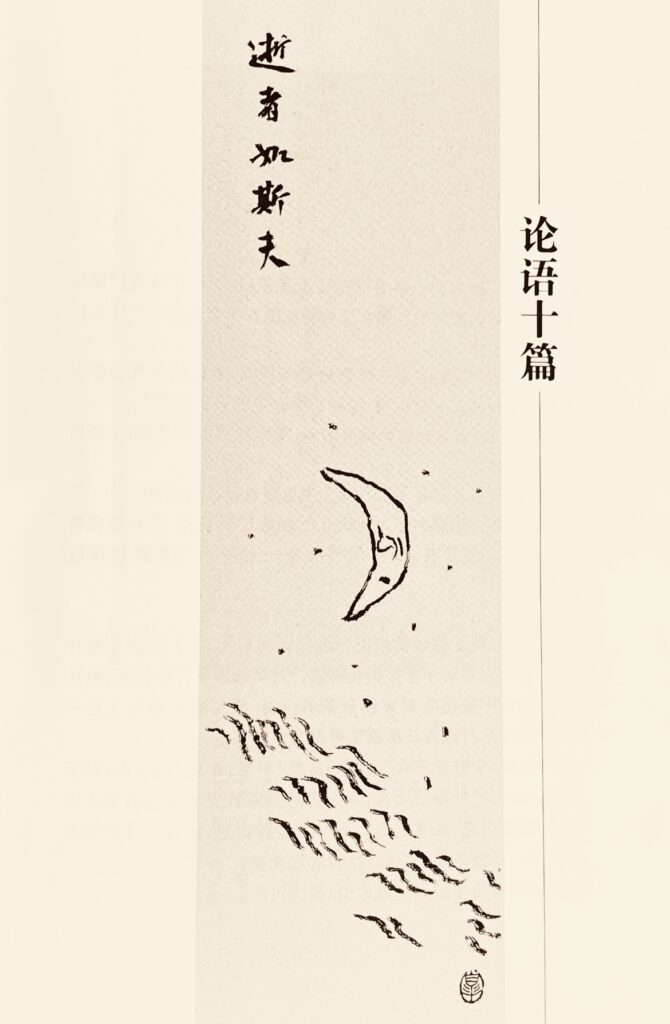

This is the third selection from the Analects of Confucius in The Tower of Reading, or Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts, by Zhong Shuhe 鐘叔河,念樓學短·論語十篇之三.

Here the focus is on the term 志 zhì, which Simon Leys translates as ‘free will’. For his part, Zhong Shuhe’s comment on the eleven characters that make up this passage in the Analects reflects his resilience in the face of the decades when free will was regarded as being inimical to the Chinese revolution.

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a series published by China Heritage focussed on the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our interpretive translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年). The short title for the endeavour in China Heritage is simply The Tower of Reading.

Each chapter features a short text of under 100 characters which Zhong translates into modern Chinese. To these Zhong appends ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, modern terms for such works, akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or a particular incident.

The Tower of Reading offers translations of the classical texts and of Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive essays along with the original Chinese versions of both.

For more on the background to this project, see Introducing The Tower of Reading.

***

In ‘I’ll drag my tail in the mud’, Zhong Shuhe speculated about what would have happened if, instead of having been approached by vassals of the Lord of Chu as he fished in the Pu River, Zhuangzi had encountered the First Emperor of the Qin. Traditionally condemned for his pitiless rule, Qin’s reputation enjoyed a dramatic reversal under Mao Zedong, who saw something of the draconian unifier in himself; he even claimed that the Communist Party had far outstripped the First Emperor in terms of thoroughgoing brutality. In his discussion of a line from the Analects below, Zhong Shuhe reminds readers of the notorious encounter between Mao, the ‘modern-day Emperor of Qin’ as many called him, and Liang Shuming, China’s ‘last Confucian’.

Mao’s cruel yet sardonic style brings to mind Robber Zhi, a scoundrel featured in Zhuangzi. Although Confucius is treated with considerable respect in the main body of that text, he doesn’t fare as well elsewhere. Here we include material from the fictional account of Robber Zhi’s encounter with Confucius, one that adumbrates somewhat Mao’s attitude toward Liang Shuming, as well as his contempt China’s men and women of letters more generally.

Since Zhong Shuhe mentions Liang Shuming’s reticence in regard to the ‘Criticise Lin Biao, Criticise Confucius’ political campaign of the mid 1970s, we revisit the Red Guard destruction of the Confucian homeland of Qufu, Shandong province, in 1966-1967. We would note, however, that the mayhem both in Qufu and throughout China in response to the Communist Party’s call to ‘Destroy the Four Olds’ 破四舊 pò sì jìu was actually the culmination of an iconoclastic temper that characterised the civil war during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom a hundred years earlier. Destructive fury also characterised the early years of the Republic of China and although the cultural heresy swelled to a crescendo during the Cultural Revolution it was merely a partial denouement of a century-long cataclysm rather than a radical departure from it. Although the material wealth of the past was pulverised, the autocratic strain of tradition remains intact.

Today, Confucius and the cult of state Confucianism are used to bolster political patriarchy while quotations from the Analects are cherrypicked to serve the power holders, as they have, on and off, since the Han dynasty. Meanwhile, messages about principled opposition to overweening power and talk about the ‘right to rebel’ found in the writings of Mencius, successor to and interpreter of Confucius, is reduced to being little more than quotable cliché.

After a preliminary study of literary Chinese in Australia, in which Mencius played a significant role, I went to university in China just as the Anti-Confucius campaign was petering out. In Shanghai, a friend and I even drafted a translation of an illustrated biography of Confucius written in the over-the-top style that was the norm. Although I appreciate the cultural and linguistic genius of the Analects and Mencius, I also retain a sympathy for those engaged in the age-old tussle to upend the role they play in China’s autocracy.

***

My thanks, as ever, to Duncan Campbell for his work on Zhong Shuhe’s Tower of Reading. My thanks to Duncan and to Reader #1 for going over the draft of this chapter and pointing out typographical errors and infelicities. The remaining blemishes are my responsibility.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 February 2024

***

Other chapters in The Tower of Reading:

- Between Master & Student — Analects, I.i

- ‘Everything flows like this’, I.ii

- Am I a Butterfly? — Zhuangzi, VII.i

- ‘I’ll drag my tail in the mud’, VII.iii

Further Reading:

- 鍾叔河著 《念樓學短》,兩冊,長沙:岳麓書社,2020年

- The Analects of Confucius, Translation and Notes by Simon Leys, New York: W.W. Norton, 1997

- The Analects, A Norton Critical Edition, ed. Michael Nylan, trans. Simon Leys, W.W. Norton, 2014

- Lin Yutang, Confucius as I Know Him, The China Critic, IV:1 (1 January 1931): 5-9

- 李零,《喪家狗——我讀論語》自序,2006年10月15日

- Guy Alitto, The Last Confucian: Liang Shu-ming and the Chinese Dilemma of Modernity, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979

- 汪東林,《梁漱溟問答錄》,長沙:湖南出版社,1988

- 戴晴,《梁漱溟與毛澤東》,2013年再版

- Mao Zedong, Criticism of Liang Shuming’s Reactionary Ideas, 16-18 September 1953, Selected Works of Mao Zedong, Volume 5, Peking: 1977

- Xu Zhangrun, Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes — a Beijing Jeremiad, China Heritage, 1 August 2018

- The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University, China Heritage, 28 April, 2019

- Feng Chongyi 馮崇義, A Scholar’s Virtus & the Hubris of the Dragon, China Heritage, 22 May 2019

***

‘That which cannot be taken away’

奪不走的

The Master said: “One may rob an army of its commander-in-chief; one cannot deprive the humblest man of his free will.”

— Simon Leys, Analects, 9.26

三軍可奪帥,匹夫不可奪志。

《論語·子罕·26》

A Comment from The Tower of Reading

In old novels, calling someone a ‘humble old fellow’ [老匹夫] was intended as an insult. And the expression ‘the courage of the humblest’ [匹夫之勇] has pejorative connotations. It was only after I had referred to The True Meaning of the Analects by Liu Baonan (劉寶楠, 1791-1855) and his son, both natives of Baoying, that I began to really understand this passage. With reference to both the Erya 爾雅, the earliest lexicon, and the Book of Documents 尚書, they concluded that what the term ‘humblest man’ referred to was just an ordinary man [匹夫 ] who might have a wife [匹婦], but did not have the wherewithal to acquire a concubine, or what today is called a ‘Little Sweetie’ or mistress.

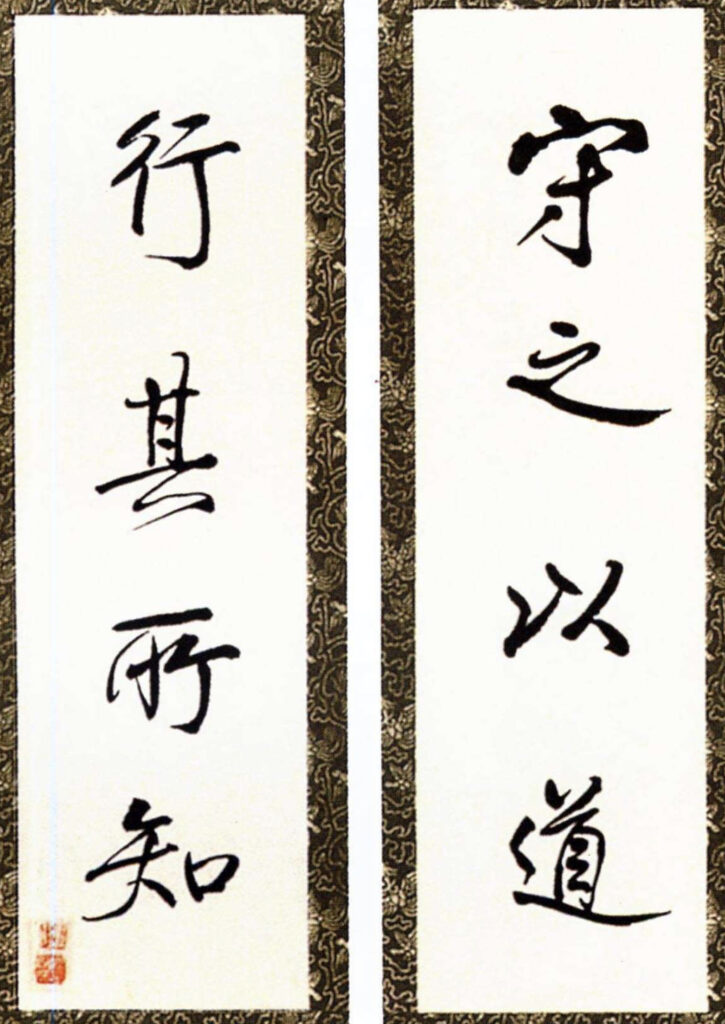

If one believes that ‘Human Rights are Natural Rights’, or innate to us, then everyone is born equal and everyone is an independent person, capable of free thought. Consequently, everyone has the right both to express an opinion and to continue to hold that opinion. This, by and large, is what the ancients meant by such expressions as establishing one’s free will [立志], maintaining one’s free will [持志] and having an inviolable free will [不可奪志]. Of course, this idea remained mostly just an ideal. Given the historical reality of autocracy in the East, it proved to be extremely difficult for even the highest ministers of state to exercise their free will and hold to opinions that differed from those of their sovereign. For the humblest people this was even more impossible. To attempt to do so would invariably incur the greatest of costs.

Naturally, things nowadays are markedly different. Because he insisted on maintaining his views [during a famous confrontation with Mao Zedong], it may well have been impossible for the philosopher Liang Shuming (梁漱溟, 1893-1988) to serve in the Central Government, but at least he could still be a member of the Political Consultative Conference; if you can’t take a cab, at least you can get along in a pedicab. Liang would later refuse to take part in the ‘Criticise Lin Biao, Criticise Confucius’ campaign of the mid 1970s. Both events demonstrated the truth of the statement that ‘one cannot deprive the humblest man of his free will’. Liang Shuming truly was a unique example of the ‘humblest man’.

— Zhong Shuhe, trans. Duncan Campbell

***

Source:

- Chapter Three in Section One of Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading 《念樓學短》,上冊,第6-7頁

***

A Note by Simon Leys

Analects 9.26:

one cannot deprive the humblest man of his free will: Epictetus said the same: “The robber of your free will does not exist.” (Epict., III, 22, 105; quoted by Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, XI, 36) Note that, here, it is not merely an elite of gentlemen that cannot be deprived of their free will (zhi [志]). This irreducible and inalienable privilege of humanity pertains to all, and even to “the humblest man” (pifu [匹夫]). Every individual, however common or lowly, possesses the full range of the human potential—he is equipped with all that is required to make a hero or a saint, equal to the greatest in history: this notion eventually found its fullest development with Mencius. (A good modern equivalent of “the humblest man,” pifu, could be the concept of “the man in the street” as understood, for example, by Evelyn Waugh. To a journalist who had said to him, “You have not much sympathy with the man in the street, have you,” Waugh gave the memorable reply: “You must understand that the man in the street does not exist. There are men and women, each one of whom has an individual and immortal soul, and such beings need to use streets from time to time.”)

— Simon Leys, Analects, p.163

***

Notes by China Heritage

- In discussing this famous line from Confucius, Zhong Shuhe employs another famous line — ‘everyone is an independent person, capable of free thought’ 獨立的人格、自由的思想. This is a famous modern formulation related to individual autonomy and intellectual independence that comes from an epitaph composed by the historian Chen Yinque 陳寅恪 for the great scholar Wang Guowei 王國維, who committed suicide in 1927. (For a translation of Chen’s epitaph, see The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University, China Heritage, 28 April, 2019.) In January 2024, Mao Yushi 茅于軾, a respected reform-minded economist, marked his ninetieth birthday in Vancouver, Canada, where he was now in exile, by copying out Chen Yinque’s celebrated encomium to which he added an epitaph of his own:

‘I’m advanced in years and not long for this world. The future belongs to the young: You should be worried about the kind of society confronting you. Just as everyone shares a responsibility for social progress, we are equally responsible for backsliding.’

我見經很老了;活不了多久,將來的世界是年輕人的。你們將面對什麼樣的社會,應該比我急。社會要進步,這是每一個人的責任。若社會倒退,也是我們每一個人造成的。

- In September 1953, the modern Confucian thinker and rural reformer Liang Shuming (梁漱溟, 1893-1988) famously clashed with the Communist Party Chairman, Mao Zedong. Liang was mildly critical of how, following the Liberation of 1949, Party policy favoured the urban working class to the disadvantage of the countryside. Until then, Mao had regarded Liang as a 諍友 zhèngyǒu, ‘a principled friend who dares to disagree’. Liang now took it upon himself to speak truth to power. During a heated exchange at a meeting of the Central People’s Government Council power spoke back. In response to a series of biting remarks that Mao directed at the scholar, Liang asked the Party Chairman if he had the ‘magnanimity’ 雅量 yǎ liàng to allow him now to voice his views at length. Mao famously replied:

‘I very much doubt that I’ll indulge you with the kind of magnanimity that you want!’

您要的這個雅量,我大概是不會給的!Mao did, however, say that he would be magnanimous enough to allow Liang a seat on the National Consultative Congress; he wouldn’t even have to perform a ritual self-criticism. But, Mao added, ‘The only thing that you have coming your way is denunciation [批判 pīpàn].’ Subsequently, the Party Chairman published a scathing attack on the scholar who, having been thus dismissed, resurfaced only because he had managed to outlive his nemesis.

Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a professor of law at Tsinghua University in Beijing and the author of a famous critique of Xi Jinping and his policies, has praised Liang Shuming as a 大儒 dàrú, a Great Scholar of Principle — here the term 儒 rú, often clumsily translated as ‘Confucian’, means ‘a man whose learning and actions are grounded in Confucian principles of righteousness, fearlessness and probity’.

On the eve of the 120th anniversary of Liang Shuming’s birth on 18 October 2013, Xu had even offered the following appraisal of the long-dead paragon in an interview:

‘Liang tirelessly traversed our nation for the betterment of all. True Confucian scholars [儒者 rúzhě] like him put Confucian thought into practice; they do so in their own lives and through their actions. They have a near religious devotion to working for the salvation of the world.

‘Nowadays “New Confucian Academics” 新儒家學者 might claim that they are Confucian Scholars but they head off to sing karaoke at the drop of a hat. Mr Liang was always mulling over issues to do with our Family-Nation-All-Under-Heaven. You must include these words when you write up your report. What’s the use of blathering on in the abstract if you don’t possess an all-encompassing perspective 眼界 yǎnjiè and true insight 眼光 yǎnguāng. Most people simply don’t get it.’

為蒼生起,奔走於大地。儒者是要實踐儒家學說,要身體力行,有一種宗教般的救世情懷,現在有一些新儒家學者,天天在說我是一個儒者,說完可能就唱卡拉OK去了。梁先生從來都是在家國天下這個大框架里來思考具體問題,你們寫文章,一定要把這句話寫進去。沒有這個眼界、眼光,瞎嚷嚷有什麼用?但這正是一般人忽略的問題。

(This note is based on the Translator’s Introduction to Xu Zhangrun’s ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ — a Beijing Jeremiad, 1 August 2018.)

- Liang Shuming’s clash with Mao Zedong features in Mao’s canonical works and, in the early 1980s, it was later the subject of studies by the writers Wang Donglin and Dai Qing during a period of de-Maoification. Their efforts were part of a broader attempt by independent writers to write counter-histories of the People’s Republic, a civil movement that has waxed and waned for over four decades. The Liang-Mao clash of 1953, also recalls a famous fictional encounter between Confucius and the villainous brigand Liuxia Zhi 柳下跖, better known as ‘Robber Zhi’ 盜跖, which is recorded in Zhuangzi. That account features an expression that has been in use ever since: ‘Submit to me and you will prosper; resist and you will perish’ 順我者昌,逆我者亡 shùn wǒ zhě chāng, nì wǒ zhě wáng is a reworking of the Robber Zhi’s warning to Confucius: 若所言順吾意則生,逆吾心則死.

Robber Zhi grants an obsequious Confucius an audience. ‘Let him come forward,’ bellows Zhi:

‘Confucius came scurrying forward, declined the mat that was set out for him, stepped back a few paces, and bowed twice to Robber Zhi. The robber, still in a great rage, sat with his legs sprawled out, leaning on his sword, eyes glaring. In a voice like the roar of a nursing tigress, he said,

“Qiu, come forward! If what you have to say takes my fancy, you will live. But if I take offense, you will surely die!” ’

盜跖曰:使來前。孔子趨而進, 避席反走,再拜盜跖。盜跖大怒,兩展其足,案劍瞋目,聲如乳虎,曰:丘來前。若所言順吾意則生,逆吾心則死。

— from ‘Robber Zhi’, Zhuangzi《莊子 · 盜跖》

trans. by Burton Watson

with modification - For a comment on the ‘Criticise Lin Biao, Criticise Confucius’ campaign mentioned by Zhong Shuhe above, see the Coda at the end of this chapter.

- The concept of 君子 jūnzǐ, one that would appear to be markedly different from the ‘humblest man’ 匹夫 pǐfū of the line from Confucius discussed in the above, also reflects the ‘individual will’ or ‘free thought’ — 志 zhì — that is championed in the Analects 論語. To Confucians 君子 jūnzǐ denotes the learned, morally sound and socially adept individual. The ‘jūnzǐ ideal’ was part of the theoretical basis of the dynastic-bureaucratic empires of China from the time of the Han dynasty. Simon Leys describes 君子 jūnzǐ in the following way:

‘Originally it meant an aristocrat, a member of the social elite: one did not become a gentleman, one could only be born a gentleman. For Confucius, on the contrary, the “gentleman” is a member of the moral elite. It is an ethical quality, achieved by the practice of virtue, and secured through education. Every man should strive for it, even though few may reach it. An aristocrat who is immoral and uneducated (the two notions of morality and learning are synonymous) is not a gentleman, whereas any commoner can attain the status of gentleman if he proves morally qualified. As only gentleman are fit to rule, political authority should be developed purely on the criteria of moral achievement and intellectual competence. Therefore, in a proper state of affairs, neither birth nor money should secure power. Political authority should pertain exclusively to those who can demonstrate moral and intellectual qualifications.’

— Simon Leys, The Analects of Confucius, pp.xxvi-xxvii

- Of course, the ‘free will’ 志 zhì of even the humblest of people can also includes a willingness to join an unthinking or self-deluded mob.

***

Original Chinese Text

學其短:The selected Classical Chinese text, with a note on the source;

念樓讀:Zhong Shuhe’s translation into Modern Chinese; and,

念樓曰:Zhong Shuhe’s interpretive comment on the text.

奪不走的《論語》

三軍可奪帥,匹夫不可奪志。

【學其短】

- 本文錄自《論語·子罕》。

【念樓讀】 孔子道:「三軍司令的指揮權,是能夠被剝奪的;人的思想和意志,即使是一個普通的人,只要他有自信,能堅持,那也是無法剝奪,奪不走的。」

【念樓曰】 舊小說寫「老匹夫」,是在罵人。常說的「匹夫之勇」也含貶義。直到讀寶應劉氏父子的《論語正義》:

匹夫者,《爾雅·釋話》:「匹,合也」《書·堯典·疏》:「士大夫已上,則有妾媵;庶人無妾媵,惟夫妻相匹。其名既定,雖單,亦通謂之匹夫匹婦。」

才明白,原來匹夫便是無權勢無力量蓄妾侍(小蜜、二奶… … )的平頭百姓。

如果相信「天賦人權」,則人人生而平等,都有獨立的人格、自由的思想,都有發表意見、堅持意見的權利。古人所云立志、持志、不可奪志,意思也差不多,但多半只是理想。因為在東方歷史上專制政治的現實中,不要說匹大,就是卿士大夫,要堅持自己不同於君王的意志和意見,也很難很難,是要付出很大代價的。

時至現代,情況當然不同了。梁漱溟要堅持自己的意見,中央人民政府委員當不了,還可以當政協委員:小汽車沒得坐了,還可以坐三輪車。後來他又拒絕批林批孔,還真的說了「匹夫不可奪志」的話,可算是絕無僅有的老匹夫了。

***

Source:

- 鍾叔河著, 《念樓學短》,上冊,長沙:岳麓書社,2020年,第6-7頁。

Appendix I

Robber Zhi

As I noted in the Preface to this chapter, I arrived in the People’s Republic of China during the Anti-Confucius Campaign in the mid 1970s. Our written assignments for class focussed on denouncing feudalism and the stain of the Way of Confucius-Mencius 孔孟之道. My early reading included a biting satire about the encounter between Confucius (Kong Qiu) and Robber Zhi 盜跖.

A.C. Graham offers a thoughtful analysis of the fictional meetings of the two men in Chuang-tzŭ: the seven Inner Chapters, see pp.234-243, but here we prefer to quote a passage from Zhuangzi that annoyed pious moralisers for centuries and today sits uncomfortably with the finger-wagging power-holders of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

‘This must be none other than that crafty hypocrite Kong Qiu from the state of Lu! Well, tell him this for me. You make up your stories, invent your phrases, babbling absurd eulogies of kings Wen and Wu. Topped with a cap like a branching tree, wearing a girdle made from the ribs of a dead cow, you pour out your flood of words, your fallacious theories. You eat without ever plowing, clothe yourself without ever weaving. Wagging your lips, clacking your tongue, you invent any kind of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ that suits you, leading astray the rulers of the world, keeping the scholars of the world from returning to the Source, capriciously setting up ideals of ‘filial piety’ and ‘brotherliness,’ all the time hoping to worm your way into favor with the lords of the fiefs or the rich and eminent! Your crimes are huge, your offenses grave. You had better run home as fast as you can, because if you don’t, I will take your liver and add it to this afternoon’s menu!’

此夫魯國之巧偽人孔丘非邪。為我告之:爾作言造語,妄稱文武,冠枝木之冠,帶死牛之脅,多辭繆說,不耕而食,不織而衣,搖唇鼓舌,擅生是非,以迷天下之主,使天下學士不反其本,妄作孝弟而僥倖於封侯富貴者也。子之罪大極重,疾走歸。不然,我將以子肝益晝之膳。

— from ‘Robber Zhi’, Zhuangzi《莊子·盜跖》, trans. Burton Watson

Appendix II

Confucius in 1966-67

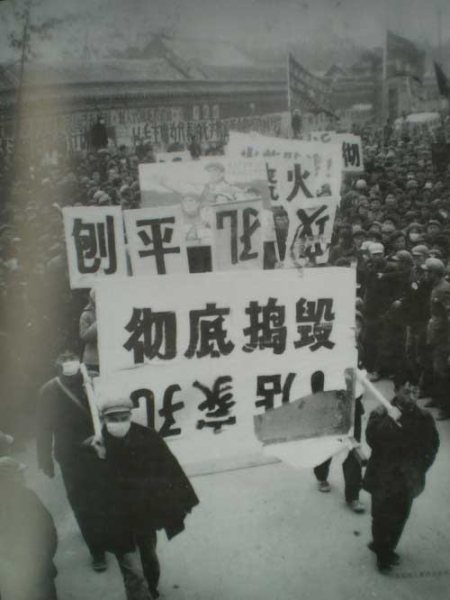

The Fate of the Confucius Temple, the Kong Mansion and Kong Family Cemetery

孔庙、孔府、孔林

Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé

The recently revived and reformulated state ceremonies held in Qufu, Shandong province 山東曲阜, to commemorate Confucius 祭孔 build on obsequies that date from dynastic and Republican times. As a background to our consideration of the reform-era commemoration of Confucius, we present here some preliminary research notes on the destruction of Confucius-related sites in Qufu, during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, 1966-67.

These notes are based on oral history interviews and memoirs as well as on the key Red Guard publication Persecute Kong Battle Dispatches 讨孔战报. That paper—which appeared irregularly from 10 November 1966 to 31 August 1967—was started by the Jinggang Shan Red Guard Corps of Beijing Normal University. They subsequently relocated to Qufu Normal College in Qufu county, Shandong province, where they joined forces with local Red Guards to set up an organization the name of which reflects the animus as well as the verbosity of the time. It was called the Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station to Annihilate the Kong Family Business and Establish the Absolute Authority of Mao Zedong Thought.

Relevant articles in Persecute Kong Battle Dispatches that have been used in writing the following account include: 《捣毁孔家店,彻底闹革命,为毛泽东思想的绝对权威而战》、《告全国革命人民书》、《革命战士向伟大领袖毛主席致敬电》、《火烧孔家店——讨孔宣言》、《井冈山战士满怀革命豪情在天安门前宣誓》、《历代农民对孔孟之道的讨伐》、《彻底捣毁孔家店,树立毛泽东思想绝对权威——孔府罪恶史展览馆介绍》、《孔孟之道、武训精神与刘氏修养》、《彻底打倒孔家店,树立毛泽东思想的绝对权威的十点建议》、《捣毁孔家店,把曲阜师范学院变成了红色的海洋》、《天翻地覆慨而慷》. Illustrations 1-6 are also reproduced from that publication.

[Editor’s Note:

One of the abiding fictions about the Red Guard phase of the Cultural Revolution from mid 1966 to late 1967 is that it was totally chaotic and anarchic. Throughout that period a feature of the murderous and destructive violence sanctioned by Mao and the Central Committee of the Communist Party was pettifogging bureaucracy, endless factional struggles over hierarchy and titles, suffocating formalism in the form of documents, speeches and public posturing, as well as mountains of red tape that mimicked the mechanisms of the party-state that the Red Guards were determined to obliterate. The following account offers an insight into how the ritualistic bureaucratic traditions of the past melded seamlessly with the revolutionary impetus of Maoism. (If one reads — reads rather than skim in a desultory fashion — the speeches, notes and commentaries contained in the official selections of Mao’s works, as well as the numerous unofficial and later compendia, the legendary master of chaos proves to be an obsessive micromanager with an eagle eye for detail.)

— GRB, February 2024]

***

The fury of the iconoclasts is a negative measurement of the permanence of the sacred powers that ruled feudal society. The tragedy is that the sacred powers dwell not in those innocent stones, whose beauty is sacrificed in vain, but in the minds of the wreckers. Seen in this light, the Maoist enterprise appears hopeless; the regime may well change China into a cultural desert without succeeding in exorcising the ghosts of the past: these ghosts will continue their paralyzing tyranny so long as the regime is unable to identify them within itself. But will it ever be capable of such clear vision?

… It [the Communist Party] can have little hope of liberating itself from the slavery of the past as long as it hunts it among old stones, instead of denouncing its active reincarnation in the ideology and political practices of the new mandarins.

— Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows, New York: Penguin Books, 1978

***

Annihilating the Kong Family Business

捣毁孔家店

The Business of Revolution

On 7 November 1966, the Jinggang Shan Red Guard Corps of Beijing Normal University (北京师范大学毛泽东思想红卫兵井冈山战斗团) gathered in Tiananmen Square en masse and swore an oath to ‘Annihilate the Kong Family Business’ 捣毁孔家店.

On 10 November, under the leadership of Tan Houlan (谭厚兰, 1937-1982), one of the original rebels at Peking University, over 200 Red Guards representatives including members of the same Jinggang Shan Red Guard Corps went to Qufu in Shandong province, the home of the Kong family, of which Confucius was the most famous member, the Kong Temple and the Kong Family Cemetery. Along with students from the Qufu Normal College they established a ‘Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station to Annihilate the Kong Family Business’ 彻底捣毁孔家店革命造反联络站.

On 12 November, the Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station requested guidance from Qi Benyu 戚本禹 and Chen Boda 陈伯达, both members of the Cultural Revolution Leadership Group in Beijing. Chen issued a directive in which he said that they could ‘hold a mass rally and dig up Confucius’ grave ‘可以开大会,孔坟可以挖掉’. Accordingly, they made preparations.

[Editorial Note: See also 张顺清,谭厚兰“讨孔”的一些事,曲阜师范大学档案馆,2017年6月14日。]

The Denunciation

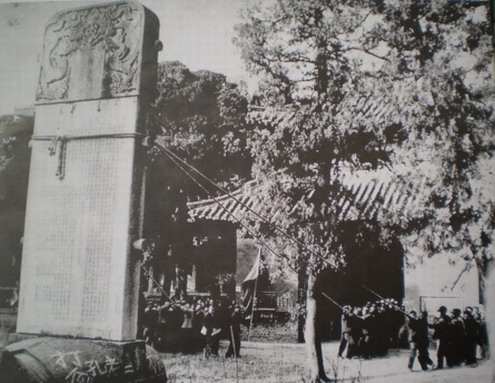

On 15 November, the Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station to Annihilate the Kong Family Business organized a mass rally outside the Kong Mansion 孔府 in the centre of Qufu and destroyed the National Cultural Relics Stelae previously erected there on orders of the State Council at the Confucius Temple, the Kong Mansion, the Kong Forest (the Kong family cemetery) and the Ancient City of the State of Lu. They also sent a formal letter of protest to the State Council for its having issued protection orders over these various ‘reactionary’ sites.[Fig. 1]

***

***

On 25 November, the Party Committee of East Wind Commune (now renamed Shuyuan Township 书院镇) received a telephone instruction from the Qufu County Party Committee ordering them to organize a team of 300 local workers into a ‘Poor-and-Lower-Middle Peasant Grave Digging Team’. Their task was to assist the Red Guard Shock Brigade in smashing stelae and digging up the tomb of Confucius. The County Party Committee would give the workers 50 cents per head per day for a job that was estimated would take two to three working days. Kong Qingju 孔庆举, the Commune Party Secretary, put Zhu Hongjiang 褚洪江, a cadre in the local civil affairs department, in charge of requisitioning the required manpower. At the same time an armed force of 20 militia members was organized to patrol the site.

On 28 November, an Annihilate the Kong Family Business Rally was held outside the Confucius Temple 孔庙 and, following speeches by Tan Houlan and other Red Guard representatives, the County Party Secretary, Li Xiu 李秀, spoke in resolute support. Zhou Yutong 周予同, a specialist in Chinese classics, the philosopher Yan Beiming 严北溟 and the historian Gao Zanfen 高赞非, all men who had participated in the last ceremony to commemorate Confucius held in Qufu in 1962, were brought in from Shanghai and other locales under guard to be ‘struggled’, that is denounced in ritualistic fashion, along with Confucius himself. Following the conclusion of the formal meeting and denunciations, the statue of Confucius in the temple was toppled and then carried through the streets of the town to be vilified.[Fig. 2] The scholars in attendance were forced into the entourage and denounced for being ‘Filial Sons and Virtuous Grandsons Paying Last Respects to Kong the Second Son’ 孝子贤孙们为孔老二送丧.

***

***

The Dig

On the morning of 29 November, Zhu Hongjiang led his team of gravediggers who were armed with picks and shovels to the Confucius Cemetery 孔林, a large enclosed area containing graves of Kong clan members. By this time, Red Guards were already busy pulling down the stone stelae and commemorative arches positioned along the spirit way leading to the main tomb. The gravediggers came across one group of Red Guards who had clambered onto an archway and were busy defacing the characters on it that read ‘Eternal Spring’ 万古长春.[Fig. 3]

***

***

The cadres of the East Wind Commune told the amassed Red Guards that there were 70 graves in the Confucius Cemetery belonging to Confucius himself and his direct descendants, as well as another 2,000 graves of Kong clan members. They warned them that it would take much more than a few days to dig up all these graves. After some deliberation it was decided that they would dig up the ‘First Kongs and the Last Kongs’ 上三孔和下三孔), that is, Confucius as well as sons and grandsons, and the last three generations of Confucius’ lineage, that is Kong Lingyi 孔令贻, his father and grandfather.

Confucius’ descendants were given the rank of marquis from the Han dynasty, and promoted to duke from the Tang. In 1055, a Song emperor bestowed the title of ‘Duke of Continued Saintliness’ 延圣公 on the 46th-generation descendant of Confucius. Kong Lingyi had inherited that title. His son, Kung Te-cheng (孔德成, 1920-2008), was the last member of the clan to hold the title; it was bestowed on him by Xu Shichang, President of the Republic of China, in 1935. At the time of the Red Guard action, Kong Decheng [aka Kung Te-cheng] was living in Taiwan.

[Note: Kung Te-cheng died in 2008 and his grandson Kung Tsui-chang (孔垂長, 1975-) was appointed to succeed him as the Sacrificial Official to Confucius.]

The Red Guards and the local Party authorities declared that the proposed plan meant that symbolically they would have destroyed the Kong Family Business ‘from beginning to end’. Thereupon, 200 workers were dispatched with the Red Guards to dig up the ‘First Kongs’ and another 100 went with Zhu Hongjiang to dig up the ‘Last Kongs’.[Fig. 4]

***

***

Reporting to Chairman Mao

That same day (29 November 1966) the mass rally composed and sent a telegram to Chairman Mao, the text of which read:

Dearest Chairman Mao,

One hundred thousand members of the revolutionary masses would like to report a thrilling development to you: we have rebelled! We have rebelled! We have dragged out the clay statue of Kong the Second Son 孔老二; we have torn down the plaque extolling the ‘teacher of ten-thousand generations’; we have leveled Confucius’ grave; we have smashed the stelae extolling the virtues of the feudal emperors and kings, and we have obliterated the statues in the Confucius Temple!敬爱的毛主席:十万革命群众向您汇报一个激动人心的消息,我们造反了!我们造反了!孔老二的泥胎被我们拉了出来,万世师表的大匾被我们摘了下来,孔老二的坟墓被我们铲平了,封建帝王歌功颂德的碑被我们砸碎了,孔庙中的泥胎偶像被我们捣毁了!

The authors of this telegram were exaggerating when they claimed that: ‘100,000 members of the revolutionary masses’ had participated in this vandalism. In reality, some 20,000 people attended the 28 November mass rally. If one includes all of the people who watched on as the tombs were dug up over the following two-day period one could claim that some 100,000 people had been involved. As for having ‘leveled Confucius’ grave’, the reality was that on the first day the grave was flattened, on the second day a three-metre deep trench was dug, but by the third day the rebels had run out of patience so they used dynamite to blow up the site. The grave was effectively obliterated.

The Loot

Eyewitnesses and participants claim that the majority of onlookers of the maelstrom were less concerned about the revolutionary action per se than seeing for themselves what treasures might be unearthed from these prestigious gravesites. They were particularly interested in the exhumations carried out at the ‘Last Kongs’ graves. Zhu Hongjiang says, ‘I led 100 people to the Qing-era graves on the eastern side of the Confucius Cemetery. I divided them into two teams of 50: one dug up Kong Lingyi and the other dug up [his father] Kong Xiangke 孔祥珂. When we unearthed the stone sarcophagi everyone rushed over to see. We decided to leave the next stage to the following day.’

On November 30, in keeping with instructions from the Qufu County Party Committee, members of the local Cultural Relics Committee and the People’s Bank gathered at the site of the exhumed ‘Last Kongs’. They were on the scene to evaluate the worth of the relics presumed to be in the unearthed coffins. The large stone coffins were broken open by being lifted and dropped from a makeshift winch. Medical personal, armed militia and Red Guard representatives oversaw the process whereby corpses were pulled out of the coffins (which included the Kong patriarchs their wives and concubines) and the confiscation of gold, jewelry and other precious objects that had been interred with the dead. The majority of onlookers were descendants of the Kong family and there were gasps of delight and shouts of excitement as each precious object was recovered from the graves. The discovery of such plunder elicited such local excitement and expectation that, given the general rapacious atmosphere, for the following three months there was something of a grave-robbing mania in the area.

The Defilement

On midday November 30, once the corpses had been removed from the coffins, onlookers took the corpses of two men and one woman to the grass nearby and stripped the other female corpses and hung them from a tree. Zhu Hongjiang recalls that, ‘The bodies were on public display for five or six days after which they were thrown into a ditch in the south-east corner of the Kong Cemetery and incinerated. People felt that so many people were coming to look at the stripped corpses—which were of both men and women—that it was best to burn them.’

One onlooker by the name of Kong Fanyun 孔繁云 recalls, ‘I’ve forgotten nearly all the details though I do have a strong memory of two odors: one was that of disinfectant, the kind you get in a hospital. It was as though they were going to operate in the open air. Then there was the stench of the corpses. It made you want to vomit. As for the atmosphere, it was just like a temple fair, there were such jostling crowds. Some were outsiders [with non-local surnames] but also members of our extended family [surnamed Kong]. Some even prodded the corpses with sticks. Forget all that stuff about ours being a noble family honoured by ages. No one bothered covering up the nakedness of our ancestral grandmothers! (什么千秋万世帝王家啊,甭说收尸,连悄悄去给光腚的祖奶奶遮块布的也没有), let alone bother taking them away’.

Victory Celebration

A quotation from the issue of Persecute Kong Battle Dispatches dated 31 August 1967 offers an ‘official’ Red Guard summation of the event. This report was composed by the Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station to Annihilate the Kong Family Business and is typical of the diction of the time:

In November 1966, a grand revolutionary army 100,000 strong swept into the Confucius Temple. They trod steadfastly on the sacrificial table set up to make offerings to Old Kong. They beat up the Sage and did just as they pleased. They split him open and pulled out his guts, then dragged him off his throne and stamped him underfoot. The dog emperors of the past have all fawned over Old Kong. They declared him to the Ultimate Sage, the First Teacher and the Mentor of Ten-thousand Generations. All the plaques with these words on them in the Temple were pulled down and burnt. Then the raging torrent swept into the Confucius Cemetery where stelae were smashed and the Kong tombs dug up. Let all those saintly people in their finery and with their solemn bearing kneel before Old Kong’s grave and eat dirt! The grave of the 76th-generation descendant of Old Kong, that big landlord and evil tyrant Kong Lingyi, was also dug up. The poor-and-lower-middle peasants split open the coffin and dismembered the corpse. They burnt that dead dog till he was nothing but ash. In righteous anger they shouted: ‘See what you’ve been reduced to, you cur!’ The masses have done an excellent thing! This was a furious denunciation of Old Kong and his promoter, Liu Shaoqi.’[Fig. 5]

1966年11月,十万革命大军涌进孔庙,踏上孔老二的供桌,在圣人头上动手动脚,为所欲为。他们开膛剖腹,掏出了孔老二的五脏,把它拉下宝座,踏在脚下。历代狗皇帝肉麻地吹捧孔老二的什么至圣先师、万世师表的大匾额也被拉将下来,一火焚之。滚滚的洪流杀进了孔林,砸碎了石碑,扒开了孔坟。让那些衣冠楚楚的圣人之徒跪在孔老二墓前啃地皮吧!大地主、恶霸孔老二七十六代孙孔令贻的狗坟也被扒开了,贫下中农开棺戳尸,把死狗烧成了灰烬。他们气愤地说“狗东西,你也有今天”!群众这种举动好极了!这是对孔老二及其吹捧者刘少奇之流的愤怒控诉。

***

***

The Statistics

The Revolutionary Rebel Liaison Station to Annihilate the Kong Family Business was stationed in Qufu for twenty-nine days. According to statistics published after the Cultural Revolution, during their stay the group was involved in the burning or pulping of some 100,000 volumes (either sets or fascicles) of classical texts of which 1,700 were rare items 善本. Some 6,618 cultural artefacts were destroyed or damaged, of which seventy were Grade One Cultural Artefacts. One thousand stelae were smashed. The interior of the Confucius Temple was destroyed and the Kong Mansion and Kong Cemetery were severely damaged. Some 5,000 ancient pines were felled and over 2,000 graves were dug up.[Fig. 6]

***

***

In reality, some of these losses were unconnected to so-called ‘revolutionary actions’ 革命行动, rather they were the result of a mass grave-digging frenzy authored by locals looking for treasure. In November 1966, only the six ancestral Kong family graves were dug up as part of the formal movement to ‘smash the Kong Family Business’, the other 2,000 graves were despoiled during the spring of 1967. As Kong Fanyun recalls:

You could start digging anywhere. The booty belonged to whoever dug it up. They say one guy dug up a tractor [that is, he was able to buy a tractor by selling what he had found as a result of grave-robbing]. Later the Production Brigade of the local People’s Commune expressed their disapproval. They felt it was unfair that outsiders and non-Kong families 外人外姓 were able to share the loot just because they dug too. So, they divided the Kong Cemetery into zones allocated to specific teams. Later on, the county government issued an order banning all digging, but by then it was too late. During the grave-digging frenzy 扒坟潮 all the graves in the Kong Cemetery and vicinity were dug up and plundered for anything of value.

And Ge Hongjiang remarks:

I was in charge of the digging, just as later on I was in charge of the people who enforced the ban. By then not one grave in the Kong Cemetery survived intact.

With the passing of the grave-robbing frenzy the Qufu Branch of the People’s Bank of China was authorised to buy the gold found in the tombs by locals and RMB101,000 was spent in the process. Following the Cultural Revolution, as the Confucius Temple and Kong Family Mansion were being restored it was deemed necessary to retrieve objects taken by locals for the new displays. The Qufu County Cultural Relics Management Committee spent RMB300,000 to buy back ‘funerary objects dispersed among the masses’ 散落民间随葬品 as a result of the revolutionary passion.[Fig. 7]

Today

On 4 April 2009, Confucius was formally commemorated as part of the annual Qingming Festival. Although he was celebrated annually on 28 September, his birthday and Teacher’s Festival, this was the first time that the ancient spring-time ritual was held for over forty years.

***

Source:

- China Heritage Quarterly, 2009, with minor revisions

***

Qufu and Confucius in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Before the end of his first year as chairman of China’s party-state-army, Xi Jinping travelled to Qufu to pay his respects to Confucius. During his tour of the sites, he pledged to read Confucian texts and praised Chinese traditional culture. He frequently quotes Confucian texts, although his speechwriters assiduously avoid material related to the virtues of independent thought and principled behaviour praised both by Confucius and Mencius. The robotic demands placed on Party members and average Chinese citizens alike are aimed a depriving even ‘the humblest man of his free will’.

As Simon Leys observed nearly half a century ago, ‘the regime may well change China into a cultural desert without succeeding in exorcising the ghosts of the past: these ghosts will continue their paralyzing tyranny so long as the regime is unable to identify them within itself. But will it ever be capable of such clear vision?’

Just as in Mao’s day, Beijing welcomes foreigners who, either out of ignorance or craven opportunism acquiesce to the grotesque Xi-era version of Chinese culture and thought, are willing to partake of what Lu Xun called ‘the banquet of Chinese civilisation’ (see below).

— GRB

***

Coda: ‘Pilin-Pikong Tinkles Like a Happy Bell’

Exoticism is not dead. At the turn of the century, during his dreamy Asiatic dilly-dallying, Pierre Loti was entranced by the sight of pale blobs, exquisitely fringed with purple, in the dark arch of a yamen; they turned out to be a string of cut-off human hands; the little girls, or boys, whom he bought here and there to while away the spleen of an Oriental night amused him with their chatter of lovebirds and their painted faces reminiscent of dwarfs painted on folding screens. Today, if we are to believe a recent article in Le Monde, the aesthetes of Tel Quel seem to have found again in China the exquisite secrets of Madame Chrysanthème’s patron. We know that the campaign against Confucius and Lin Piao has already caused blood to flow: a friend, an English Sinologist returning from Nanking, told me he saw the names of the first batch of people executed in this campaign posted on the walls there, and similar reports have reached us from Canton and Wuhan, while in Peking wall posters told of massacres in Kiangsi. But Roland Barthes, confronted with such posters, would no doubt see only calligraphy “with a grand lyrical movement, elegant, willowy,” and the willowy, enigma of those graceful hieroglyphics would not bother him much — now that he has discovered how ridiculous we are “when we think that our intellectual task is always to try to find a meaning.” Also for him, the very name of the purge taking place under cover of an anti-Confucian campaign, “in Chinese, Pilin-Pikong [批林批孔], tinkles like a happy bell, and the campaign expresses itself in newly invented games: a cartoon, a poem, a skit by children, during which suddenly, between two dances, a little girl, all made-up, strikes down the ghost of Lin Piao; the political Text (but only that) causes these tiny ‘happenings.’ ” Lu Hsün made the point: “Our much vaunted Chinese civilization is nothing but a banquet of human flesh prepared for the rich and the powerful, and China is merely the kitchen where that meal is cooked up. Those who praise us can be excused only in as much as they do not know what they are talking about, such as these foreigners whose high status and comfortable life has rendered them absolutely blind and obtuse.”

— Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows, New York: Penguin Books, 1978, pp.198-199

***