Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXXIV, Part IV

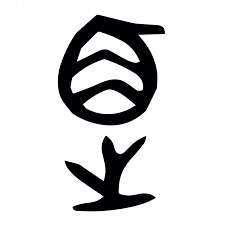

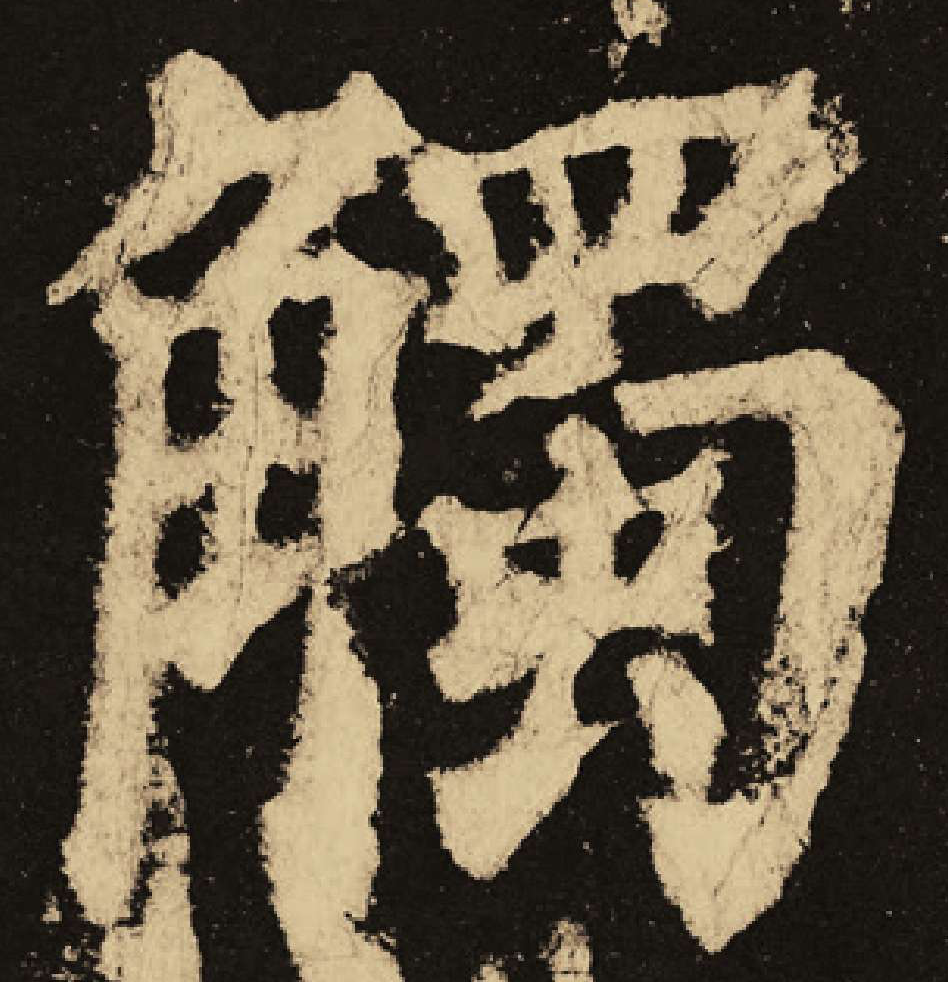

羝羊觸藩

Chapter Thirty-four of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the penultimate chapter in the collection, features a series of essays related to China’s intellectual life and its stillborn public sphere. Four of the five sections in this chapter were published over the years leading up to the Xi Jinping era. Given that most of this material was not previously available in digital form, I decided to digitise and publish them as background to the final chapter in Tedium, the title of which is ‘An Irrealis Mood’. A version of that concluding chapter was drafted for ‘Knowledge, Ideology and Public Discourse in Contemporary China’, a conference organised by Sebastian Veg and held at L’École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHEES) in Paris on 13-14 June 2024.

This chapter consists of the following sections:

- Time’s Arrows

- The Revolution of Resistance

- Have We Been Noticed Yet?

- Chinese Visions: A Provocation

- On China’s Editor-Censors

- Ethical Dilemmas — notes for academics who deal with Xi Jinping’s China

The first three of these works, written between 1998 and 2001, were a continuation of a series of commentaries, academic analyses, translations and books that I published from 1978 that include: records of my encounters with Ai Qing and Ding Ling in 1978 and 1979 respectively, The Wounded (1979), my contributions to Trees on the Mountain (1983), an overview of the 1983 Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign (1984), Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience (1986, rev. ed. 1988), the Chinese-language essays on culture and politics published in The Nineties Monthly (1986-1991), extended studies of Liu Xiaobo (1990) and Dai Qing (1991), New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices (1992), my contribution as lead academic adviser and writer to the documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995), as well as the books Shades of Mao: the Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (1996) and In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999). The last two — A Provocation (2007) and Ethical Dilemmas (2016, 2023) — relate to China’s relative openness at the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the lengthening shadow of the Gate of Darkness 黑暗的閘門, yet again, from 2012. ‘On China’s Editor-Censors’ is one of Xu Zhangrun’s Ten Letters from a Year of Plague. Today, its message is more resonant than ever.

***

The following text was drafted in collaboration with Gloria Davies and Timothy Cheek in late 2006 as a proposal for an international conference on the topic of ‘Chinese Thought, History and the Present’. Invitees were also sent two Chinese-language versions of the text, one translated in the style of Mainland Chinese academic prose, the other suited to colleagues in Taiwan and Hong Kong. The more elegant translation, made by the historian Warren Sun 孫萬國, is appended below.

The conference was held at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, in August 2007 and was funded by Monash University, Geremie Barmé’s Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship and the University of British Columbia. The conference proposal was subsequently published in the December 2008 issue of China Heritage Quarterly and included in what was then still a small body of material related to New Sinology.

By and large, participants in the August 2007 conference itself ignored the suggestion made in our ‘provocation’ to think more expansively about Chinese engagement with issues beyond ‘The China Question’ 中國問題, an over-riding obsession of thinkers for well over a century and the resulting ‘gabfest’ achieved little more than reflecting the entrenched positions of many of the speakers. It did, however, have some positive, albeit unintended, consequences and a conversation with Mark Leonard, the director of the European Council on Foreign Relations, in 2009 encouraged me to continue our efforts.

In 2010, this led to a collaboration involving Gloria Davies, Timothy Cheek, Mark Elliott, William C. Kirby and Klaus Mühlhahn that presented its preliminary findings at a panel devoted to the topic of ‘The Prosperous Age 盛世’ at the annual conference of the Asian Studies Association in March 2011, which were then published in an dedicated issue of China Heritage Quarterly titled China’s Prosperous Age (Shengshi 盛世), published in June 2011. Thereafter, we organised ‘Re-reading Levenson’ an informal project focussed on Joseph Levenson’s seminal work Confucian China and its Modern Fate (published as a trilogy in 1967) that led to a symposium of the same name held in Sydney, 17-19 December 2013. Organised by the Australian Centre on China in the World, that symposium was led by Geremie R. Barmé (Australian National University), Timothy Cheek (University of British Columbia), Gloria Davies (Monash University), Madeleine Yue Dong (University of Washington), Mark Elliott (Harvard University) and Wen-hsin Yeh (University of California Berkeley) and invited participants included Leigh Jenco (London School of Economics and Political Science), Liu Qing (East China Normal University), Qian Ying (ANU), Will Sima (ANU), Brian Tsui (ANU) and Xu Jilin (East China Normal University). For a report on the symposium, see Gloria Davies, The Practice of History and China Today, The China Story, 26 August 2015.

Following the founding of the Australian Centre on China in the World in April 2010 [link], conversations with colleagues in China led to a joint workshop with East China Normal University in Suzhou in September 2010 focussed on new directions in Chinese academic work. We hoped to develop a section devoted to contemporary Chinese thinkers on The China Story website being planned for the new centre. My main collaborator, Xu Jilin, averred that we best focus on three main intellectual/ academic currents — Liberals, the New Left and Neo-Confucians. Those he regarded as having marginal and dissident view, were problematic, even irrelevant. Having known Jilin for nearly two decades, during which time I had seen him duck and weave through moments of political repression, naturally I understood the reasons for this ‘strategic elision’ — no, let’s call it by its name: censorship.

Our difference in purview of Chinese intellectuality had already been evident when, on Christmas Day 2009, the Beijing authorities announced that Liu Xiaobo had been sentenced to eleven years in jail for ‘inciting subversion’, a charge linked to the leading role he had played in drafting Charter 08, a manifesto for the kind of liberal society that, in his academic work, Xu had long praised.

In January 2010, an unofficial (and in China unpublishable) poll of leading thinkers, rights activists, lawyers and writers, was unanimous in condemning the absurd charges against Liu and the harsh sentence meted out to him by the Party-dominated legal system. Missing from the protests were leading Leftists, Neo-Confucians and, among others, Xu Jilin. Subsequently, Jilin questioned whether Charter 08 could even be regarded as being part of China’s ‘public sphere’. To be fair, however, he did join seventy-one others in signing A Proposal for a Consensus about Reform 改革共識倡議書 in December 2012, just as Xi Jinping came to power. Jilin’s uncharacteristic participation in this mild form of public advocacy was widely noted.

Given the divergence in our views, however, I had already pursued our project on the landscape of Chinese intellectual life with Gloria Davies and, in mid 2012, we launched Thinking China as part of The China Story project. As we noted at the time:

Thinking China is an attempt over time to document Chinese thinkers and thinking, scholarship and intellectual enquiry. Our aim is to feature Chinese voices, arguments and accounts that allow English-language readers better understanding the many (often conflicting) strands that make up The China Story.

That project continues, albeit fitfully, today. In December 2015, Gloria (via video link) and I joined Timothy Cheek, Xu Jilin and David Ownby for a workshop on Reading the China Dream, an endeavour that grew out of various conversations that can be traced back to Chinese Visions: A Provocation. We proposed Chinese Visions with an open-ended invitation for freewheeling thinking and discussion, we end this reverie with a question that has haunted China since Mao Zedong declared war on arrant thinking in 1949: who gets to think, how and when can they do so, and who are the gatekeepers who get to decide?

We remind readers of an observation that Gloria Davies made in her introduction to an essay by Rong Jian titled A China Bereft of Thought 沒有思想的中國, published in 2013 and included in Reading the China Dream:

The question as to how authoritarian power has affected scholarship and inquiry in China is seldom openly discussed but the effects of authoritarian power are everywhere evident, among other things, in the exercise of self-censorship and the resulting characteristically oblique nature of mainland intellectual discourse.

***

Gloria Davies, Timothy Cheek and I share more than intellectual synergy, we also had the same mentor, Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys, 28 September 1935-11 August 2014).

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

11 June 2024

***

Related Material

- Gloria Davies, Worrying about China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007

- Thinking China, The China Story (2012-)

- Reading and Writing the Chinese Dream: A Collaborative Research, Reading and Translation Project, The China Story, 26 January 2015

- Geremie R Barmé, Rock Stands and Mud Washes Away, The China Story, 18 November 2015

- Gloria Davies, The Practice of History and China Today, The China Story, 26 August 2016

- Xu Jilin, “The New Tianxia”, Reading the China Dream

- Rong Jian, Thoughtless China, The China Story, 20 February 2017

- Introducing Translatio Imperii Sinici, China Heritage Annual 2019

- May Fourth at 105 — Protest, Resistance, Repression, 1 May 2024; May Fourth at Seventy, 4 May 2024; Captive Minds & Academic Angst on May Fourth 2024, 8 May 2024

***

Chinese Visions: A Provocation

Gloria Davies, Geremie R. Barmé and Timothy Cheek*

Since the late-nineteenth century, thinking people in China have sought to produce ways of knowing that combine both the modern and the Chinese. In reflecting on this disposition or xintai 心態, the eminent literary historian C.T. Hsia remarked that a certain ‘obsession with China’ had prevented the modern Chinese writer from identifying ‘the sick state of his country with the state of man in the modern world’. We appreciate profoundly the historical circumstances—local and international, dynastic and imperialist, social and cultural—that have generated the need for Chinese people of conscience to be obsessed with the Chinese situation, the imperatives of national salvation and the conditions of modernity.

We also recognize that the insistence on identifying and being consumed with what are framed as uniquely ‘Chinese problems’ 中國問題 is something that can be detected in Chinese intellectual discourse to this day. Indeed, the use of terms such as ‘modern Chinese thought’ and ‘contemporary Chinese thought’ is often accompanied by the assumption that they designate a set of ‘properties’ and an overall enterprise that is somehow unique to China, which itself is figured as a holistic project in its own right. In addition, writings produced in aid of improving ‘Chinese thought’ often reflect a desire for that which is Chinese to achieve eventual parity with ‘Western thought’.

Since the civilizational connotations inherent in the expression ‘Western thought’ are derived from different European languages, not to mention disparate albeit overlapping histories, the term can readily be disaggregated into different geopolitical and cultural combinations and descriptions (such as EuroAmerican, Continental, AngloAmerican, French, Italian, German thought, and so on), or the thinking of particular individuals. Unlike ‘Chinese thought’ which projects the image of a singular civilization generated by individuated effort but ‘unified’ in the Chinese written language, ‘Western thought’ has always been divided from within: it projects a civilization developed out of the intellectual traditions articulated in and across different European languages through ceaseless, often raucous, conversation. In contemporary articulations, these traditions are fostered but questioned, enhanced while simultaneously being subjected to constant self-critique and challenge. While the institutionalization of ‘Western thought’ is the legacy of the power historically exercised through the divided interests of rival empires and nations, retrospectively coalesced into the figure of the ‘West’, engagement with ‘Western thought’ by thinking people in non-European cultural environments has and can enrich and enliven ‘Western thought’ on a global level.

In ‘Western thought’ of recent years, much concern has been expressed about the threat to inclusive openness posed by border security and the creation of a new victimhood. Writing in this vein, the thinker Zygmunt Bauman described Europe (a territorially diffuse, cultural multifarious and socially complex realm) as ‘an ideal’ that ‘defies monopolistic ownership’. In doing so he affirmed Hans-Georg Gadamer’s notion that ‘We are all others, and we are all ourselves.’ Bauman also argues that Europe, conceived of in civilizational or cultural terms, should signify ‘a mode of life that is allergic to borders—indeed to all fixity and finitude.'[1]

We take Bauman’s argument as being illustrative of a general drift in contemporary Western thought among those who, in rejecting the security fixation of contemporary politics, choose to figure Europe as a repentant victor who must now undo the ‘barbarism’ it inflicted along with the ‘civilization’ it sought to impose on the non-European world. In this regard, although the conflation ‘Euro-America’ remains relevant in the field of critical inquiry, the distance between the ‘European’ and the ‘American’ has clearly widened in politics. Furthermore, in the geo-political and intellectual spaces on the borders of latter-day economic and cultural empires—among, for instance, people in the former ‘dominions’ of Australia and Canada—there is perhaps an intellectual open-endedness and productive unease that encourages our interrogation of certitudes affixed both to the ‘Euro’ and to the ‘American’.

The discussions revolving around such themes as the ‘return to tradition’ [回歸傳統] and the ‘establishment of academic norms’ [建立學術規範] that have shaped much Chinese intellectual inquiry since the 1990s sit somewhat at odds with Bauman’s meditation on Europe, and perhaps offer a productive challenge to competing global visions. After all, these activities seem oriented towards a different ideal: that of restoring China to civilizational grandeur and regulated practice, together with the expectation of recovering or discovering, as well as delimiting, the borders of what is unique to China and Chinese culture. We also discern in Chinese intellectual inquiry a desire to learn from the West those things that would benefit China which reflect a moral imperative resonant since the time of Mencius, namely the art of ‘knowing what to adopt’ 取 and ‘what to discard’ 捨. In our discussions, perhaps we should consider whether there is a particular way of cultural being in China that, contemporary politics aside, cleaves to the holistic, generates meaning in particular and compelling ways, and tells us all something unique about the human condition.

Thus, while it is important that we discern different speaking positions and sensibilities in contemporary Chinese thought, we should note that an overarching perspective persists: that of a recovering victim attempting to redress the tragedies of historical barbarisms, both Western and Chinese, while working towards new and better ways of ‘being Chinese’. We are drawn to ask, therefore, if the following claim, pace Gadamer, is implicit in contemporary Chinese thought: ‘Because we have been othered, we must now learn once more how to be ourselves’?[2]

We are concerned that in an age of unprecedented global exchange, borders—intellectual as well as territorial—are being re-articulated in a manner that may threaten to deprive thinking people of the wealth of thought and difference. We therefore invite you to reflect on the complex and challenging ramifications of this asymmetry between ‘Chinese thought’ and ‘Western thought’. We take up Bauman’s point that ‘European life is conducted in the constant presence and in the company of the others and the different, and the European way of life is a continuous negotiation that goes on despite the otherness and the difference dividing those engaged in, and by, the negotiation.'[3]

We wish also to consider how the wealth of Chinese experience—an experience as vital, continuous, nuanced and multifarious as the Chinese world itself—engages both with some of the big and the small questions related to the human condition. Can therefore our condition be discussed without, to recall C.T. Hsia’s lament, obsessive concern with more narrow conditionalities? And so it is that we wish to explore with you how Chinese thinkers, while pursuing the needs of an intelligentsia in the specific socio-political and historical framework of the present, are engaging more deeply with issues related to our shared humanity, and through this forum to contemplate what that engagement may mean for us all.

Many Chinese intellectuals have written about what they regard as the indiscriminate embrace of ‘imported ideas’ characteristic of twentieth century Chinese thought, but few have articulated ways in which the productive assimilation of such ideas can over time contribute to ways in which Chinese ideas can circulate more widely in the global context—and how the international currency of Chinese thought will nourish the way we all think about and inhabit a world culture of which China is a constituent and central part. In brief, China has yet to be affirmed as a mode of life that exceeds all fixity and finitude. As the attention of the world focuses on China on the eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, we believe, therefore, that this is an ideal juncture—and Australia a suitably distant, though not far flung, locale—for a gathering of people who share a common love and concern for the living legacy of Chinese thought and scholarship. We also believe that as China looms as an international presence, it offers extraordinary riches and possibilities as a world civilization. It is our hope that from within Chinese thought and scholarship epochal articulations may emerge of what it is to be particularly Chinese that are also meditations on what it is to be human.

It is in this spirit of inquiry that we would like you to join us in further conversation, one that will unfold in a mood of fraternal/sororal curiosity and innovative possibility. While many intellectual positions have been iterated and reiterated in Chinese cultural debate over the past fifteen years, some coalescing into camps of thought and collectives of temper, we make bold here to suggest a moment of renewed consideration and cooperative meditation. We hope to avoid the common academic circumstance that sees well rehearsed positions entrenched, controversy generated for the sake of notoriety and contrarian views advanced in a spirit of disruption. Ours is a hope for an unsettling of all positions in the spirit of fresh and exciting inquiry. We would propose that by stepping back from the tedious frenzy of contestation, Internet immediacy and public posturing, perhaps room can be found for a more tranquil and generous consideration of the aims and methods of thinking itself.

Thus, after this lengthy preamble, we offer you a ‘provocation’: As China continues to rise to a position of global and regional economic and political power, what lessons can Chinese thought teach a world where Western intellectual paradigms and cultural sensibilities remain dominant, a world in which international media reports often reflect an attitude of apprehension and suspicion towards China’s rise?

We invite you to explore with us the ways in which new trajectories could be mapped for Chinese thought, to render it relevant to joint present-day and future global concerns and to our senses of history, culture and society. We hope that our conversation will range over issues such as how Chinese and Western ideas might be further brought into conversation with each other, or further engage in a commingling and evolution. We propose this also in the interest of facilitating more effective inter-cultural conversations on issues such as social justice, minority rights, modernity and postmodernity, globalization, democracy and cultural pluralism. We seek also to draw attention to China’s rise and the concomitant anxieties attached to larger cross-border issues of bio-ethics, sustainability, the environment, nation-state diplomacy and personal politics, and so on: issues that engage the attention of thoughtful participants in intellectual community everywhere.

In brief, then, we invite you to contemplate the relevance of Chinese thought and Chinese ways of being on a planetary scale.

In this regard, we conceive of our gathering as organized around five broad themes: History and its Times; Traditions in Modernity; Cultural Difference; Intellectual Publicity; and, Heritage and Being. If you agree to join us, we invite you to contribute a substantive paper that takes as its focus one of these themes, or suggest ways to expand our inquiry and conversations.

Themes

History and its Times

In China, reprisals of recent histories denied by political will are joined by the histories of eras past; collectively they clamour for a place in contemporary China, its markets and the imaginative landscapes of its peoples. Intellectuals and culture creators, social engineers and party thinkers alike have been engaging in a sifting and reconsideration of Chinese history, thought and culture now for many years. Imagining what could, and can, unfold in China has led many thinkers to re-examine various paths to modernity, including those leading to other political futures, versions of bicameral democracy, social democracy and socialism that were curtailed by war, revolution, political cupidity, opportunism and sheer mischance. Concomitantly, dynastic times, and the thinking of pre-modern writers, have found a vital place within China’s conversation with itself about identity and history. Such efforts can perhaps be spoken of as a form of ‘reflective nostalgia’, a term that Svetlana Boym coins to mean a positive, or active, nostalgia among those who are, as she writes in The Future of Nostalgia, ‘concerned with historical and individual time, with the irrevocability of the past and human finitude. Re-flection suggests new flexibility, not the reestablishment of stasis.’ Thus, as a theme, ‘history and its times’ is phrased in deliberate resistance to any anticipation of recovering a singular or absolute truth, or indeed a linear narrative. Rather, it is an invitation to meditate on the ways in which history can and does project different passages or trajectories of time either singularly or synchronically.

Tradition and Modernity

As projects of cultural or civilizational restoration, New Confucianism and ‘national studies’ [國學] have attracted both praise and criticism. Although many regard the call to learn and master the contents of traditional scholarship as a necessity for developing Sino-centered ways of knowing and thinking, some have expressed concern that it might also encourage an unhealthy conservatism or an indulgent antiquarianism at the expense of critical engagement with present-day concerns. We would like you to ponder what the ‘return to tradition’ or New Confucianism might contribute to critical inquiry both within China and globally. For instance, traditional Chinese scholarship has always reflected a desire to recover from the past the true moral structure of the known world. Does this desire still resonate in the different kinds of historicization now underway, ranging from Jin Guantao’s and Liu Qingfeng’s macrohistorical project, Zhongguo xiandai sixiangde qiyuan 中國現代思想的起源 to Wang Hui’s critical survey of modern Chinese thought, Zhongguo xiandai sixiangde xingqi 中國現代思想的興起? If Bauman’s ideal Europe is ‘a mode of life that is allergic to borders—indeed to all fixity and finitude,’ what are the ways in which China could be envisaged as an ideal mode of life? In posing these questions, we invite you to explore with us the critical and reflective dimensions of historiography, of history as a process of re-transcription and reinterpretation that effects a transformation of the received past. We also invite you to consider whether the traditional Chinese emphasis on the moral and spiritual significance of scholarship remains of relevance for contemporary inquiry.

Cultural Difference

In his recent work A Cloud Across the Pacific: Essays on the Clash Between Chinese and Western Political Theories Today, Thomas Metzger provides a detailed study of the differences between Chinese and Western modes of theorizing. He characterizes these differences, among other things, as Chinese ‘epistemological optimism’ versus Western ‘epistemological pessimism’. Many Chinese intellectuals have also written about perceived differences or even incommensurabilities between Western and Chinese modes of inquiry. In this regard, we note that deconstruction, a highly self-reflexive form of Western critical discourse, is often either misconstrued or ignored in Chinese critical discourse. We also note that when the writings of prominent Western social theorists such as Jürgen Habermas are discussed in Chinese, a transformation of Habermas’s ideas takes place that reflects the different purpose they serve in Chinese critical discourse. Accordingly, we invite you to discuss how you perceive the differences between Western and Chinese ways of thinking and writing; to reflect on the types of ‘Western theory’ that have exercised an influence on Chinese intellectual inquiry since the twentieth century; to reflect on the types of ‘Chinese theory’ that have emerged since the 1980s; and, to consider how Chinese and Western ideas might be further brought into conversation with each other, in the interest of facilitating more effective inter-cultural conversations on issues such as social justice, modernity and postmodernity, globalization, democracy, and cultural pluralism.

Intellectual Publicity

One shared experience of critical inquiry in China and ‘the West’ is the experience of being an intellectual or being seen or designated as an intellectual. While specific definitions vary over time and place, and the relationship between intellectual and ‘professional’, ‘expert’, ‘artist’, and even ‘revolutionary’ or ‘entrepreneur’ remains contested everywhere, thinking and engaged individuals in every society continue, nonetheless, to speak to broad and compelling social and ethical problems. Given the constraints under which intellectual publicity is performed in China—and the contested nature of public dissent elsewhere—what constitutes public intellectual praxis, or the activities of the ‘critical intelligentsia’? How is the appeal to and the engagement with the ‘public’ (which itself is evoked simultaneously with open intellectual practice) realized? If engaged Chinese thinkers are to speak beyond the specificities of the ‘Chinese situation’, how are broader issues to be addressed, and what are they? We also invite you to reflect on the tradition of voicing public concerns in twentieth century China and to consider the ways in which this tradition has been continued and modified via the Internet. In this regard, what is ‘public’ about being an intellectual? What right or authority does an intellectual invoke in addressing, advising or speaking for a public? Should an intellectual in China today be anything other than critical? We ask you to consider these questions in relation to the present-day complexities of becoming associated with a cause or voicing a concern in mainland China, and how that relates to the articulation of China outside of itself.

Heritage & Becoming

‘Cultural heritage’ 文化遺產 has become a mainstream discourse in China in recent years. This complex concept plays many roles: it is commonly used to codify cultures; it is used to preserve and enhance vital elements of the past; it is also a term that legitimizes particular accounts of the past. In this regard, ‘intangible cultural heritage’ 非物質文化遺產 is a concept that has enabled China’s policy makers to sidestep the moralising and judgmental categories of ‘quintessence’ 精華 and ‘dross’ 糟粕 that previously informed historiographic morality and attitudes to tradition and specific aspects of the Chinese past in the early decades of the People’s Republic. It is a concept that liberates tradition from the pejorative notions of ‘superstition’ and ‘feudalism’, rubrics once used to damn much of China’s pre-1949 tradition. Although ‘intangible cultural heritage’ is grounded in an artificial distinction between the ‘material’ and the ‘spiritual’, a bifurcation generally viewed with skepticism by Western conservationists and heritage theorists, Chinese cultural officials and ideologues well versed in a clear-cut rhetorical and ideological dichotomy between materialism and idealism have put the concept to good use. ‘Intangible cultural heritage’ is often an implicit reference to the urgency of preserving the ‘best’ of traditional culture. Cultural policy makers are thus able to use ‘intangible cultural heritage’ to acknowledge, accept, document, resuscitate and preserve aspects of China’s tradition that were once threatened or slated for condemnation, destruction, suppression and elimination. At the same time, the notion of ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has recast many historical practices and traditions as museum exhibits or decorative items that can make no ideological impact on current beliefs, customs and lifestyles. Such acts of preservation can offer us a more open-ended view of Chinese culture, when the plurality of practices and beliefs are affirmed. But they also have the effect of reinforcing an orthodox view of culture, its multifarious (and often contradictory) strands, and its possibilities. We invite you to reflect on the cultural ramifications of the new emphasis on heritage, both material and intangible.

— January 2007

Notes:

* This provocation is the result of an ongoing conversation between Gloria Davies and Geremie Barmé on the future of Chinese thought, one that they first pursued in the late 1990s and have since sought to elaborate in their individual work as well as collaboratively. It constitutes an extension of the work undertaken in Gloria Davies, ed., Voicing Concerns: Contemporary Chinese Critical Inquiry (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), and draws substantially on issues raised in Gloria Davies, Worrying about China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 2007); Barmé and Davies, Have We Been Noticed Yet? Intellectual Contestation and the Chinese Web, in Edward Gu and Merle Goldman, eds., Chinese Intellectuals Between State and Market (London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon 2004); Geremie R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975) (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); Barmé, After the Future in China (Review supplement, The Australian Financial Review, 31 September 2006); and, Barmé, On New Sinology, Chinese Studies Association of Australia Newsletter, No. 31 (May 2005), pp.5-9. It also draws on Timothy Cheek, Living with Reform: China Since 1989 (Zed Books, 2006); and, Cheek, Xu Jilin and the Thought Work of China’s Public Intellectuals, China Quarterly 186 (2006): 401-420.

[1] Emphasis in original. Zymunt Bauman, Europe: An Unfinished Adventure (London: Polity Press, 2004), p.7.

[2] Davies, Worrying about China.

[3] Bauman, Europe.

Chinese Translation by Warren Sun:

放長眼,量宇內,敢請中國思想界

—中國思想的未來國際研討會前言

黃樂嫣、白杰明、齊慕實

孫萬國譯

洵自19世紀末葉,中國的有思之士便汲汲於探索如何結合「現代的」與「中國的」的各種認知方式。在檢視這一心態時,文學史名家夏志清即曾指出其中「對於中國意識的執迷」,並認為此一迷障阻礙了現代中國作家的視野,未能中西共察,「只見中國之病態,卻不知世人亦患有現代(主義)之通病」。(換言之,中國學人實未能結合「現代」與「中國」,平等觀照。) 對此現象,我們深表理解與衷心同情。蓋中國情狀,自有其歷史因緣。姑不論其為本土因素、國際因素、社會背景、文化背景、滿清王朝的腐朽、或西方帝國主義的侵凌,這些都迫使中國有識之士,執著於本國的處境與民族存亡的大業,以及如何「走上現代」的諸多先決條件的問題。

我們也注意到,迄至今日,這一堅持中國獨特、並稱之為「中國問題」的態度,在當前中國的思想話語與學術市場里,仍然處處可察。而所謂「現代中國思想」或「當代中國思想」,這一術語本身就伴含著一系列認定為中國「特質」 或「屬性」的假設。總之,中國就是中國。在思想上,自成一整體,不容拆解;自成宇宙,不容假借。即便向外求索,以期圓滿」中國思想」,其終極目的還是企圖與「西方思想」分庭抗禮。

相形之下,「西方思想」這一概念及其文明的內含涵,則淵自不同多樣的歐洲語言、及其相異但又交疊的歷史發展。根據不同的地緣政治與文化組合,人們不難將其拆解成歐美思想、歐陸思想、英美思想、法國思想、意大利思想、德國思想等等,乃至於特指個人的哲學。然而「中國思想」總是呈現出一個單一文明的形象。侭管它包含了諸多哲人個別的努力,卻總是整合統一於亙古不變的中國文字之下。而「西方思想」則從不忌諱其內部的分裂。它本演化自多元的學術傳統、從不休止的對話,甚至喧囂的爭議。在當代的西方學界里,這些傳統既得進一步的滋養與發展,也同時受到不時的質疑和挑戰,並進行自我批判。雖說早已悍然建立的「西方思想」大廈確是」西方」政治(經濟)與文化權力經歷對抗與組合的遺產,但由於歐洲境外各地學者的參與介入,「西方思想」完全可以——並且已經——在全球的層面上,變得更加豐富、更為活跳。

唯近年來,某些當局鼓吹邊境安全並製造新的受害者的政策,嚴重地威脅及「西方思想」中的包容性與開放性。這就引發了許多思想家的憂慮與關切。為此,鮑曼(Zygmunt Bauman)把歐洲(一個領土分散、文化多面、且社群複雜的地域)描述為一個「反對壟斷佔有」但「尚未實現的理念」。這也就是重申了伽達默爾(Hans-Georg Gadamer)的觀點:「我們既是他者,又是我們自己。」(按此不妨解為「唯我中有他,此我乃真我」)。鮑曼還論述道:若視為一個文明或文化的概念,歐洲當是指「一套厭憎疆界–或任何成型不變和畫地為牢–的生活方式」。

在我們看來,鮑曼的論辯正代表了當代西方思想界中的一大趨勢。即拒斥當前大打邊界安全牌的國際政治,進而選擇把歐洲描繪成一個懺悔的勝利者,必須立刻為其「野蠻」的勝利懺悔,並清除其強加於非歐世界的「野蠻文明」。就這方面而言,儘管在文化批判領域里依舊有「歐-美」並提之說,但在現實政治上,歐-美相背的距離顯然已見擴大。除此而外,在處於現代經濟與文化帝國邊緣的國家裡,例如先前還是英屬的澳大利亞和加拿大,由於地緣政治的考慮和較為中性及開放的思想空間,其學界亦似乎存在著對於歐-美過於自信的自我界定感到不安,並不斷從事建設性的質疑。

如此看來,中國自九十年代以來,以「回歸傳統」和「建立學術規範」為主軸所進行的思想探討,顯然與鮑曼關於歐洲的思考大不合拍。但也有可能對當前具有全球性眼光並考慮全球未來的各種思潮,構成有益的挑戰,並與之一爭短長。迄今中國思想活動的走向與「理想」,畢竟與他人不同。總是企圖重歸中華文明的輝煌,企圖通過規範的學術實踐,以期恢復固有、或重新發現中國思想或中華文化獨特的邊界,乃至於打破或突破先前的設限。當然, 我們也察覺出中國思想界企圖「學習西方,以利中國」的欲求。這顯然反映出自孟子以來有關「義利之辨,知所取捨」的那套高明藝術。不過,在本次的研討會中,或許我們最好集中考慮一下,在中國,撇開政治不談,究竟有沒有一種特殊的文化存在(cultural being),一方面體現出哲學上的「整體主義」(the holistic),一方面又能滋生出個別的、可信的思想意義,並能對人類世界的處境貢獻出獨到的見解。

鑒於當代中國思想界所展示的諸多言論,其立場和情思雖或相異其趣,總不外是為受害的中國奮起,向各色野蠻主義開火。不論其為西方帝國主義或是中國封建殘餘,以討回悲劇歷史的公道(在此我們進一步借用了鮑曼的暗喻)。或者就是致力於新的途徑「成就中國」,及「成就為掃淨糟粕,取盡精華的中國人」。我們自然要追問,(記否伽達默爾的觀點?),當代中國思想中,是否已隱含了這一前提:「我們既已遭人異化,如今須當復歸自家」?

對此重提楚河漢界的傾向,不論是地域的邊界,或是思想上的華「夷」之辨,我們都不免為之擔心。如今在史無前例的全球交流時代,這些界限是否會削減了思想差異的多元價值,也剝奪了世人本可共享的思想財富。因此,我們邀請閣下對「中」「西」思想背馳與失衡的現象,及其可能產生的複雜後果,進行反思。在此我們不妨重申鮑曼的觀點:「歐洲人的生活之道,總是在他者和異類的日夜伴隨之中成長起來的;歐洲的生活方式是一場持續不斷的談判,一場不斷與他者和思想異類的洽商,不論介入談判與洽商的諸方如何分歧。」

我們還希望閣下思考,以中國豐碩的文化經驗——此一經驗猶如中國實體的世界那樣活生、持續、細緻、和多面——如何能與全人類的處境掛鈎? 積極參與其中或鉅或微的問題? 而且,希望在我們的研討會中能避免夏志清的感嘆,避免只狹隘地沈湎於中國的處境。反之,我們祈望能夠放開視野,與你們共同探索此一課題:即中國知識分子如何在當前本國的社會-政治與歷史的框架下肩負起士大夫的職責之余,能否深刻地介入域外,參與思考具有人性普遍意義及世人息息相關的問題。若然,則這一變化在人類思想史上又有何等意義?

在中國,不乏學人著書立說,認為不加擇別地擁抱「舶來理念」乃是二十世紀中國思想之特徵。可惜罕見有人論述這一思想領域上實則可喜的中西融合,若假以時日,能否促使中國思想在全球範圍中享得更為廣泛的傳播與影響,並使之成為國際流通的思想貨幣,參與造就出一副與人共享的世界文化。當然, 在此世界文化中,中國自該是一個中樞的組成部分。簡而言之,中國仍有待被確認為我們先前所說那種超越「固定化」與「有限性」的生活方式。如今適逢2008年北京奧運的前夕,世人即將聚焦中國。我們相信,這正是絕好的時機,邀請共同關愛中國思想與學術遺產及其未來的學界朋友,前來澳大利亞,薈聚一堂。澳洲雖遠,並非偏僻,亦可謂坐而論道的寶地。我們也相信,隨著中國在國際政治與經濟平台上的赫然聳現,她完全可能在思想的範疇上,貢獻其哲學財富,成就為全球性的文明。我們深盼,在回答「何謂中國的個性?何謂普遍的人性?二者能否交融並濟?」這一問題,換言之,在如何「成就中國特殊的自體,又同時成為人類的共同體」這一課題上,劃時代的創見能夠終於在中國思想和學術的圈內湧現出來。

正是本著這一探索精神,並基於兄弟手足般的誠懇,與乎大膽求新的好奇心思,我們希望閣下加入行列,展開進一步的對話。儘管許多思想觀點在中國過去十五年的文化論爭中已屢見提起和重申,乃至出現了各種思想陣營與情緒上的壁壘分明。我們在此則斗胆建議諸位平心靜氣,聯手同桌,重新思考這些課題。我們希望能避免學界熟見的場面,諸如重彈老調愈演愈烈;為了揚名立萬不惜挑起爭論,或持破壞之念故做反對派。反之,我們則期望諸君以一新耳目、振奮心神的相互探討,來動搖各家既有的立場。不論是瑣碎的亢奮鬥氣、互聯網式的急就章、或著當眾的故作姿態,顯然都無助於討論的開展。我們只有從之退卻,或許才可以讓出一個足夠的空間,對哲學思辨本身的目的與方法,進行清涼的、寬容的清理。

以上冗長的序言收尾之際,我們送呈一副牛虻之貼,請君回答這一關鍵的提問:如今中國已儼然崛起為全球和區域性的經濟與政治大國,方興未艾,同時又因此招徠世人的惶恐和疑慮,如國際媒體所見。在此情況下,面對仍受西方科學典範及文化情操所支配的外在世界,到底中國的思想及文化對於世人能有何種指教?

換句話說, 我們敬邀請閣下共同勘察中國思想運行的新軌跡,如何使之與當前和未來的全球性的關懷、以及與如何看待歷史、文化和社會的諸多問題上,緊密掛鈎、息息相關。總之是,如何促使中西理念進一步對話,更加融合、同流並進。本著這一跨文化對話的精神, 我們但願諸君 開懷暢談以下諸題,如社會正義、少數族群之權利、現代與後現代現象、全球化趨勢、政治民主,以及文化多元性等等。也請思考諸如生命倫理學、發展可持續性、環境保護、邦國外交,以及獨夫政治等問題。這些超越國界的重大問題,正是中國的崛起引發國際憂慮後各地學人至為關切的課題。

「風物長宜放眼量」 。 在此,我們邀請諸位立足於全球的角度與氣派,思考中國的思想及中國人的生命之道究竟與全球的人文世界有何干系?

關於這次的思想聚會,我們準備圍繞著五個寬廣的子題展開:歷史與過去或歷史與它的各個時代 (History and its Times)、傳統與現代性 (Tradition and Modernity)、文化差異(Cultural Difference)、知識分子的公共性(Intellectual Publicity)、文化的舊符與新桃或遺產與存在(Heritage and Being)。閣下如能大駕光臨,則請就其一子題,為我們貢獻出一篇有份量的論文。對於此會的課題與形式,各位如有更好的建議, 我們當然樂於聽取和擴展。

— 2007年元月

***