Translatio Imperii Sinici &

a Lesson in New Sinology

‘The Beginning of the End’ is Part IV of ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’, Jianying Zha’s coruscating reflections on the legacy of the ancient thinker Han Fei and the Legalist school in Xi Jinping’s China.

This essay is presented as a ‘Lesson in New Sinology’, one of a series focussed on the kinds of ‘literary-historical-intellectual’ 文史哲 usage and allusions that are a central feature of contemporary Chinese politics and culture, an understanding of which is essential for those who hope to engage seriously with the Chinese world. It is also a chapter in Translatio Imperii Sinici, a China Heritage series that traces some of the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which continue to influence the Chinese world in a myriad of ways.

This concluding chapter in Jianying Zha’s powerful study of Prince Han and Chairman Xi is followed by an editorial postscript titled ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Xi Jinping

Part IV: The End of the Beginning

Jianying Zha

查建英

Empire Redux

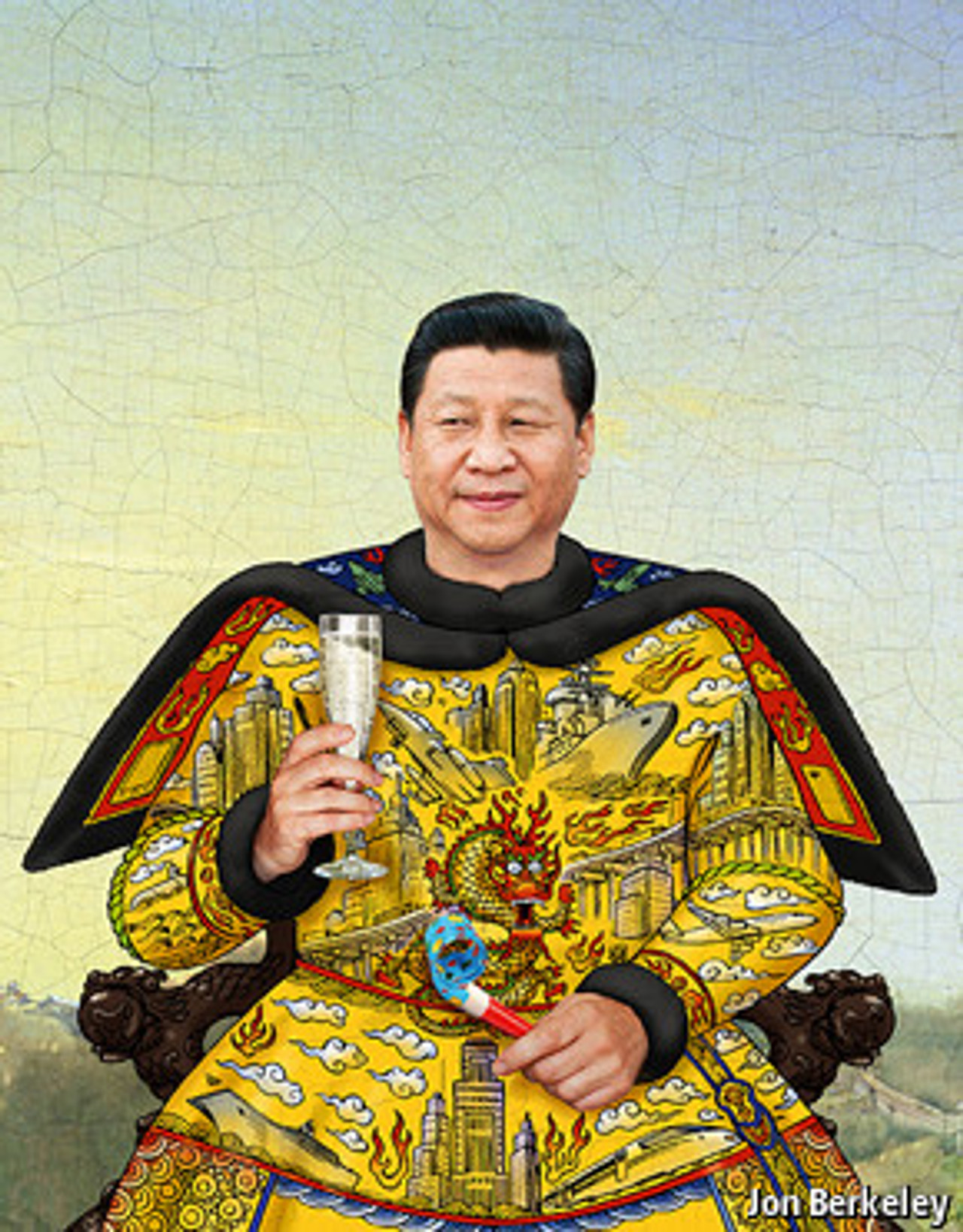

Meanwhile, there are abundant indications that the growing resemblance between the party-state under Xi Jinping and late-dynastic China have been registered and keenly observed within China itself. Reactions to this convergence more than a century after the abdication of the last dynastic house in January 1912, depending on who you talk to, run the gamut from sardonic amusement to disbelief, abhorrence to jubilance. For a public that over the past decades has been able to enjoy a constant stream of popular TV series about court life, imperial intrigues and the stories of emperors, the evolving affinity between the past and present, between what they watch on their screen and what they can observe in the reality around them is not too difficult to grasp. From the early 1960s, Mao and his wife Jiang Qing had called for Chinese culture to be purged of ‘traditional scholars and fey beauties’ 才子佳人 along with ‘emperors, kings, generals and ministers’ 帝王將相 in part out of a concern that the habits, language, ideas and behaviour of the past constantly threatened to re-infect the present. On reflection, maybe they had a point.

Language, as always, serves as both a mirror and a weather-vane. In everyday parlance people have long reverted to using pre-Communist terminology. For example, the traditional term 官 guān, official or bureaucrat, has long been used instead of the official sanctioned 幹部 gànbù, cadre. A corrupt cadre is called a 貪官 tān guān, while one who does their job as they should is hailed as ‘an upright official’ 清官 qīng guān. Even the official media deploys this language.

In online discussions about affairs of state, netizens have also long been in the habit of employing such dynastic terms such as 天朝 tiān cháo, ‘heavenly dynasty’, when referring to the People’s Republic. ‘Founding Emperor Mao’ 毛太祖 Máo Tàizǔ, frequently stands in for Mao Zedong, and 今上 jīn shàng, ‘the reigning emperor’, is used to refer to Xi Jinping. Employed in part to evade censorship, such linguistic prestidigitation allows people to exchange sly cultural parodies and pungent political critiques; even then, the verbal veil is so thin everyone can recognise the dramatis personæ and appreciate the salient metaphor. Equally commonplace is the use of the classical term 盛世 shèngshì, ‘golden or prosperous age’, and the capacious ancient concept 天下 tiān xià, the ‘all-under-heaven’ Sinocentric world. For almost two decades now, these ancient notions have been invoked in both official and popular media, as well as extrapolated in academic circles.[19]

[Note 19] For a discussion of 天下 tiān xià, see ‘The Heritage of T’ien Hsia, All-Under-Heaven’, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 19 (September 2009); and, for 盛世 shèng shì, see ‘China’s Prosperous Age (Shengshi 盛世)’, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 26 (June 2011)

***

***

Vintage revivals seldom occur by accident. Notwithstanding raving internal contradictions, everything in this one, whether we call it The Return of the Dragon or The Way of the Dragon Redux, makes a certain amount of sense. And then, with Xi Jinping taking center stage, the revivification of the past has accelerated. His appearance on the political stage — although some who have yearned for another True Dragon Son of Heaven 真龍天子 might say he has lit up the firmament — offered at once a focal point for many divergent hopes, fears and ideas to congregate, as well as providing an outlet for people at all points on the political spectrum to vent pent up hopes. It wasn’t just the small clusters of ‘Gorbachev Dreamers’ — that is, liberal intellectuals, rights lawyers and so on, who were hopeful of a long-delayed Chinese-style glasnost/ perestroika — who observed Xi Jinping’s rise while insinuating into it their own projections. Many others had eyes rapt on the new ruler: there were the old Maoists, the young Little Pinks, the born-red second generation Party gentry, neo-liberal mercantilists, State Confucianists, the anti-Western-hegemon New Leftists, military hawks, cyber-war strategists, the security-maintenance fanatics and right down the food chain to neighborhood committee grannies, as well as every other ‘Third Zhang and Fourth Li’ 張三李四 lurking in the shadows — all ‘necks craning in expectation’ 翹首以待. Watching. Wondering. Waiting.

To these hopefuls who had pricked up their ears, or were supplicants with bent knee and rigid bodies who crowded the scene in various degrees of suspended animation and anticipation, Chairman Xi’s statements and acts did not disappoint. He addressed the people and the nation as directly as any Chinese leader could, tirelessly and exhaustively. He laid out his politically honed vision about how the Party would lead in maintaining Good Laws 善法 shàn fǎ and delivering Orderly Governance 善治 shàn zhì.[20] He visits Qufu in Shandong province, the birthplace of Confucius, site of a grand Confucius Temple and the graveyard of the Confucius clan where the tombs stretch back to pre-Qin times. While there Xi fondles canonical texts and talks about their abiding value. Symbolism aside, early on he also displays an iron will in rooting out and punishing corrupt ‘tigers’ — although they are carefully selected malfeasants whose removal will benefit the consolidation of power. He visits poor peasants in remote villages with seeming avuncular civility, but he also makes grand gestures by reviewing ostentatious military parades orchestrated according to his will. He hosts lavish state banquets and constantly grants audiences to visiting foreign notables who line up to pay court to him. He calls on his people to advance resolutely on a New Long March, the route of which he is both architect and guide. And he enjoins world leaders to participate with him in building a ‘community of shared destiny’, the outline of which is his and his alone. A New Silk Road, he promises, will expand and reach All Under Heaven.

[Note 20] Again, these two were terms taken from the tradition of Chinese statecraft. See, for example, Xi Jinping, ‘在部級主要領導幹部學習貫徹十八屆三中全會精神全面深化改革專題研討班上的講話’, 17 February 2014

‘立善法於天下,則天下治;立善法於一國,則一國治。’ — 王安石,《周公》

What Kind of Ruler?

With a sword in one hand and a book in the other, the Chairman of Everything aims to impose Law and Order Chinese style while acting as an ethics and civics teacher. He is a demanding but wise father figure. He is omnipresent; his impact is felt everywhere and this much is clear: he is a ruler determined to leave a mark on history, one that rewrites China’s fortunes and its global significance.

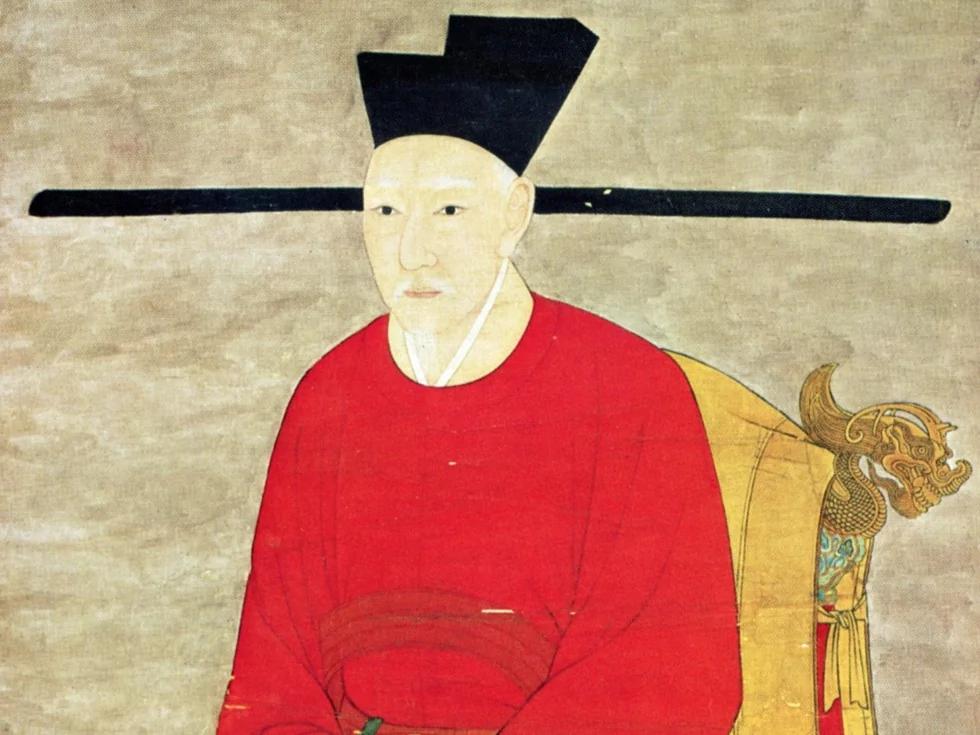

There are four terms that, over the ages, have been used to categorise China’s rulers. They are:

聖君 shèng jūn, the sage-king;

明君 míng jūn, the wise or perspicacious ruler, a term we also translate as ‘the all-seeing lord’;

昏君 hūn jūn, the hapless martinet; and,

暴君 bào jūn, the tyrant.[21]

Han Fei had declared that his political ideas were designed so that any kind of rulers could implement them to great effect. As great sage-kings, as well as vile tyrants, were a rarity, Han Fei reasoned, and since run-of-the-mill sovereigns were of average talent regardless of their innate abilities or failings, if a ruler was only willing to pursue his unique 法 fǎ, or methodology, and follow his advice to promote capable officials rather than merely relying on their own, often woefully inadequate, proclivities, they too could aspire for Wise Rule. If they failed to do so, Han warned, they risked that they would end up as a willful and addled lord under whom the kingdom would founder.

Han Fei used the terms 明君 míng jūn and 明主 míng zhǔ when referring to a ruler who had the requisite wisdom to enact the kind of Legalist doctrine that he prescribed. In other words, even though all rulers were his target audience, not all would be deemed worthy of the honour, or acclaim of being a Wise Ruler. For us today, the question is: just how well has Xi Jinping learned the lessons of Prince Han? Is he turning out to be a 明君 míng jūn or just another 昏君 hūn jūn in the long history of arrogant failures in Chinese history?

[Note 21] Of the four categories, the first is a rarity, and the title has only been accorded posthumously to a number of mystical emperors from antiquity. They are: Yao 堯, Shun 舜, The Great Yu 大禹, and Tang 湯. They were all said to be benevolent sage-kings and over the ages they were held up as models of the ideal ruler. If Confucius had his way, the pantheon would also include King Wen 周文王 and King Wu 周武王, the first two rulers of the Kingdom of Zhou. The last category, that of the ‘Tyrant’, is usually reserved for the most infamous despots, such as Jie 桀, Zhou 纣, as well as Qin Shihuang. For many today, Mao Zedong proved himself worthy of joining their ranks.

All other rulers from pre-Qin to dynastic times, can be located somewhere along the spectrum between these two extremes. Those who stand out from the majority of the mediocre, colorless emperors are labeled either Wise Rulers or Hapless Martinets. Generally speaking, the former usually refers to an enlightened autocrat who champions competent government and efficacious rule, that is 善法 shàn fǎ and 善治 shàn zhì, whereas the latter refers to corrupt or misguided dullards who cannot tell right from wrong, nor good from bad.

***

***

At this point in Xi Jinping’s term-less tenure, among thinking people of my acquaintance opinion remains divided. While state media loudly promotes the image of Xi as the ever-perspicacious leader, in the popular realm it would seem that many have quietly reached a very different conclusion. Jokes about Xi as a dolt or a wannabe pretender are common among the educated liberals in private conversations or on social media, though the strict policing of unflattering remarks about the Chairman makes it impossible to gauge how widely Xi is regarded with contempt.[22] But let me cite just one example of someone whose political sensibilities are far more conservative than the average liberal dissident. He is senior partner at a Beijing business law firm and one of my Peking University alumni friends. Over the years he has repeatedly come out with the trite line that: ‘China simply isn’t ready for democracy because most Chinese just want a good emperor.’

Only six years ago this lawyer believed that the legal reforms Xi was championing would lead to cleaner, better governance. Initially excited about Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, he described the secret inspectors that Xi and Wang Qishan dispatched to the provinces as nothing less than 御史大夫 yùshǐ dàfū, an old title for officials in the Imperial Censorate 御史台 which was established during the Qin dynasty and lasted into the Qing. Serving as ‘the eyes and ears’ 耳目 of the emperor, these inspectors would investigate local official malfeasance and report directly back to the throne. When Xi cast the first few corrupt ‘Big Tigers’ into the cage, my lawyer friend was hopeful. But he has long since become utterly disillusioned. ‘The best scenario for China is that the next ruler really is a 明君 míng jūn,’ he recently told me. ‘Unfortunately, Xi may stay in power for another decade, or more, and he is clearly a 昏君 hūn jūn.’

[Note 22] See, for example, Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear’, ChinaFile, 10 February 2020; Xu Zhiyong 許志永, ‘Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go’, ChinaFile, 26 February 2020; Josh Rudolph, ‘Essay by Missing Property Tycoon Ren Zhiqiang’, China Digital Times, 13 March 2020; and, ‘Former Party Professor Calls CCP a “Political Zombie”,’ China Digital Times, 12 June 2020.

My lawyer friend is disappointed, I think, because he has come to see Xi as a bad emperor even in Han Fei’s terms.

In the first place, Xi has failed to pursue his version of 法 fǎ ‘Law’ in a uniform and even-handed manner as suggested by Han Fei. The Xi-Wang anti-corruption campaign has been highly selective and the inspectorate has willfully turned a blind eye to all the corrupt Red Princeling Families 紅二代家族 whose support he assiduously cultivated before and since coming to power.

Secondly, a ‘discerning ruler’ in the Han Fei mould would never promote so many mediocre flunkies or, for that matter, surround himself with a bevy of sycophants.

Thirdly, Han Fei’s ideal Legalist sovereign would wisely practice 垂拱而治 chuí gǒng ér zhì, an ancient, somewhat Taoist notion of ruling from a supreme remove through calm, aloof authority, not by frenetic micromanaging. Xi’s ego is formidable, something on display with near comic effect at the tragic time of the Covid-19 crisis when, after a period of unexplained silence, he came out and boasted that throughout the crisis he had ‘personally organised’ the response 親自部署 and that he had been in personal direct management of it 親自指揮.

And, finally, how exactly is resurrecting outdated laws and a mouldy ideology, as Xi Jinping has done, a way of ‘keeping up with the times’? ‘He is going backwards’, said my lawyer friend. Hence, for him, Xi has turned out to be an un-enlightened autocrat: a 昏君 hūn jūn.

***

***

Nonetheless, all indications are that there are deep fissures between members of urban elites and the ordinary people when it comes to Xi Jinping’s achievement. Some people are indeed impressed by the efficacious manner in which Xi harnessed the bureaucracy and consolidated power. To those people, doesn’t that prove that he is a strategic and strong ruler? Others might also be dazzled by what he presents as a lofty and seemingly idealistic vision or, for that matter, seduced by the extravagant media hype about the amazing record of Chairman Xi’s leadership. Aren’t we lucky to live in such a steadily advancing and well-ordered country? Hasn’t President Xi elevated China’s global standing and won us more respect throughout the world? Behold: he is loved by the people who have called him ‘Xi Dada’ (Uncle Xi). He is revered by the Party and the nation as The One 一尊, and he is praised by leaders from Europe to Africa.[23]

[Note 23] The One 一尊 yī zūn refers to Xi Jinping’s newly ordained emperor-like status, which is reflected by the ancient expression ‘定于一尊’, that is ‘everything is determined by the Supreme One’, translated elsewhere in China Heritage as ‘The Ultimate Arbiter’. The imperial-era term is now a regular feature in the official media, as well as in Xi’s own affirmation of the role of the Communist Party, of which he is the head.

***

China has never suffered from a dearth of people who worship brute power, or indeed from hot-headed nationalists, career opportunists, or shrewd servants of the state. At the mere inkling of a powerful new ruler being on the horizon, such toadies swarm to the fore, fall into line and genuflect with awe-struck, craven, calculating hearts. They are eager to serve the state. They are ready to obey The One.

Yes! The voices from the swelling echo chamber in which The One presides chant: Our nation’s moment has come! It’s time to take pride in our glorious tradition and in the outcomes of our arduous experimentations (艱辛的探索, a Partyspeak euphemism used to gloss over the decades-long murderous failures of Party policies from the 1950s). It’s time to harness all resources and connect the dots between our ancestors and our fathers; to re-synthesise Han Fei and Confucius, to iron out the wrinkles between Mao and Deng; to put all the genies and gods from East to West into the bottle and give it a good shake. Poison shall be turned to elixir, weakness into strength, corruption and degeneration transmuted into law and order. We shall ceaselessly promote and reward ‘positive energies’. We shall, above all, focus on the collective of the ‘China Nation’ 中華民族 [This common expression usually translated as ‘Chinese’, ‘Chinese People’ or ‘Chinese Race’, is a relatively recent term for all of the ethnic groups subsumed by the geopolitical territory of modern China — first as a republic and subsequently as a people’s republic — it is thus a hegemonic term for what by all rights is a multiplicity. — Ed.], the ultimate expression of which is the People’s Leader 人民領袖.[24]

[Note 24] To sample just one influential mainland Chinese legal strategist’s work which attempts to formulate a twenty-first-century vision for an authoritarian Chinese civilizational-party-state that is being constructed around a Legalist-Leninist Führer figure — that is, Xi Jinping, I recommend the work of Jiang Shigong 强世功. ‘Reading the China Dream’, a website curated by David Ownby and Timothy Cheek, offers translations of two works by Jiang that are relevant to the present discussion: ‘Philosophy and History: Interpreting the “Xi Jinping Era” through Xi’s Report to the Nineteenth National Congress of the CCP’ 哲学與歷史:解讀習近平十九大報告; and, ‘The Inner Logic of Super Large Political Entity — Empire and World Order’ 超大型政治體的内在邏輯——帝國與世界秩序.

***

***

Hark! The One Exhorts the People

‘Don’t forget our original intention, remember above all our mission.’ 不忘初心,牢记使命。

‘Roll up your sleeves and work harder.’ 擼起袖子加油幹。

‘We will successfully complete the Long March of our generation.’ 我們一定能夠走好我們這一代人的長征路。

‘The China Dream shall be realised!’ 中國夢一定能實現!

In this fashion the talking-heads who natter away on every media platform in China have whipped themselves into a frenzy, especially as they have observed the millennial global shift in the winds: after decades of growth and prosperity, China is once again a great power, whereas the West…let’s just say it’s not as great as it used to be. As for MAGA — in China Trump 川普 is mocked as 川建國 — ‘Trump the One Helping Build China’! Despite the looming economic downtown and a mountain of social ills in the People’s Republic, the blithely jolly mood in Beijing was evident at the annual forum convened by Global Times, the party-state’s flagship nationalist tabloid in December 2019. The title of forum encapsulated the mood of national hubris: ‘2020: Dilemma in the World, Good Governance in China’ 世界之困,中國之治。

Consider this: the forum took place on 21 December 2019, just as the first cases of coronavirus were becoming evident in Wuhan. Thanks to official obfuscation, the panelists in Beijing could still merrily (and literally) shoot the breeze and pat each other on the back in blissful ignorance. Who could come up with a more gratuitous topic than theirs? Or one that completely fails to disguise the organiser’s Schadenfreude? But hubris is the default modality of Global Times, a media outlet that specialises in yellow journalism. It is a self-satisfied, gloating source of prideful exaggeration and its editors never tire of putting an insidious and Spenglerian spin on global affairs, one in which an orderly and superior China faces off a chaotic and declining Western world. Totally unconscious of its own bad taste, the paper has carried on its proselytising right through the Covid-19 pandemic, touting the China Solution 中國方案 at every turn.

As Confucius might say, advising an inferior person 小人 xiǎo rén that epicaricacy doesn’t accord with the refined character of a gentleman 君子 jūnzǐ is a vainglorious task. Indeed, to use an expression from the Han dynasty, it would be as useless as ‘playing a harp to an ox’ 對牛彈琴.

The Heart of Darkness: The End of the Beginning

In hindsight, the writing was on the wall from Xi’s first days in power. Now it’s easy to pin down the stealthy moves that signaled the shifting wind, the crucial moments that marked the inflection points. To become The One, Xi had to engineer the following:

Grasp the two handles tightly;

Fill all available space in the public realm;

Occupy the moral and ideological high ground;

Impose your version of the rule of law without flinching; and,

Clean your house and wipe out all vermin.

But wait on: vermin? Yes, vermin. Otherwise known as enemies of the state: wayward, cliquish officials, potential challengers, two-faced intellectuals, probing journalists, stubborn lawyers, unruly artists, conniving NGOs. Their number is legion; they are the nonconforming malcontents of all kinds. Vermin is anyone who doesn’t submit to The One.

And this is how a ghost glides up to a dead body, to use an old expression: 借屍還魂 jiè shī huán hún, ‘to reanimate a corpse with a different soul’. From the start you could discern the mummery of the past. There it was in the odious Document Number Nine, a secret internal Party edict issued soon after Xi Jinping took office. Titled ‘Communique on the Current State of the Ideology Sphere’, the document was formulated and initially distributed to senior officials and apparatchiks in 2012 and then reissued in early 2013 with instructions that it was to be implemented, both in spirit and in word.

In stark terms, the document delineated the cleavage between the party-state’s ‘socialist core values’ and the universal values of the global community. It identified seven dangerously subversive undercurrents that were coursing through China’s body politic and its educational institutions. Danger number one was the Western political system itself, the vaunted concept of ‘constitutional democracy’. Hostile forces had long been promising this so-called universally valid idea to undermine and negate the leading role of the Communist Party. Other ideological ills that had infiltrated the nation included such erroneous concepts as liberty, human rights, civil society, the freedom of speech and the press, neoliberalism, and so on. The Centre instructed that all of these seven ills had to be eradicated in thought, word and deed. In other words: identify and eliminate the vermin and clean up the public sphere.[28]

[Note 28] For a detailed report on Document Number Nine, see Chris Buckley, ‘China Takes Aim at Western Ideas’, The New York Times, 19 August 2013.

Document Number Nine was couched in the New China Newspeak [link] of contemporary officialdom, but the tone and sensibility were eerily familiar from an earlier time. The sombre formulations, the paranoid mindset, the pragmatic outlook, the dark warnings and, above all, the steely intolerance.… A shadowy figure was being brought back to life; I can almost make out Prince Han’s knowing smile.

***

‘The Five Vermin’ 五蠹 is one of the most famous chapters in Hanfeizi. Mao learned it by heart in his youth. In it Han Fei identified five types of people, the ‘five vermin’, who plagued society. From influential scholars to silver-tongued lobbyists who peddle ideas on behalf of foreign interests for their selfish ulterior motives; from cliquish wandering knights to greedy private merchants — all of these disloyal and subversive elements may threaten a sovereign’s authority, disrupt social harmony and undermine the security of the state. Han Fei’s advice was clarion: they must all be rooted out and eliminated.[29]

[Note 29] See Geremie R. Barmé, ‘The Five Vermin Threatening China’, China Digital Times, 5 November 2012.

The authors of Document Number Nine would have been familiar with Han Fei, just as many in China’s party-state are au fait with the thinking of the Dark Prince. Like countless power-brokers from time immemorial, they, too, pay homage to the brilliance of the gimlet-eyed Prince. How sharp his observations! How prescient his advice! How eternally fresh his strategies!

Do not ignore these insights, do not lower your guard, for your enemies shall never cease to seek your ruin. Be vigilant always, rule forcefully by law, so the altar of the state will stand, proud and strong.

Thus spoke Han Fei, in his eternally modulated voice, from the heart of darkness, addressing Chinese rulers past, present and future.

Drafted in April 2019

Revised during January 2020

Finalised in July 2020

Manhattan, New York City

***

Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes

An Editorial Postscript

Geremie R. Barmé

In the opening paragraphs of her study of the nexus between Prince Han Fei and Chairman Xi Jinping, Jianying Zha notes that when Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, a celebrated legal scholar at Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, was ‘unceremoniously stripped of his teaching position and placed under official investigation’ in March 2019, she happened to be re-reading Hanfeizi, the decoction of Han Fei’s Legalist thinking, in an attempt to understand better the draconian rule of Xi Jinping. As Zha observes:

‘Censorship, arrest, imprisonment, police harassment, reeducation camps — after six years of a top down “civil war”, Xi Jinping and his coterie have broken the back of their opponents as well as of nearly all potential enemies of the Chinese party-state. Wherever they have been hiding, be it in the ranks of officialdom, within the sprawling commercial and state media, the academy or within civil organisations, malfaiteurs have been identified and rooted out. Crushed. Cowered. A web of high-tech surveillance is being cast far and wide. An army of grassroots informants are mobilised in schools and neighborhoods. The vast population of the country and its territory are on the authorities’ radar. Law and order, as formulated by the Communist Party, are being rigorously enforced. National security and social tranquility are to be achieved and maintained no matter the cost.’

— from Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

We have followed the writings, and the fate, of Xu Zhangrun in the virtual pages of China Heritage since August 2018 (see our Xu Zhangrun Archive) and, just as we serialised Jianying Zha’s insightful meditation on Han Fei and Xi Jinping in July 2020, in Beijing Xu Zhangrun was being detained, defamed, cashiered from his job and deprived of his professional standing. Then, without explanation, he was released. (For details, see: ‘無可奈何 — So It Goes’ and ‘Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People’.)

Jianying Zha’s timely observations on the legalistic rule of Xi Jinping resonate with Xu Zhangrun’s warnings. In a now-famous critique of Xi’s globally consequential mishandling of the COVID-19 epidemic in China from late December 2019, Xu declared that Xi Jinping’s New Epoch was nothing less than:

‘…an evolving form of military tyranny that is underpinned by an ideology that I call “Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism” [Fa-Ri-Si 法日斯], one that is cobbled together from strains of traditional harsh Chinese Legalist thought [Fa 法; that is, 中式法家思想] wedded to an admix of the Leninist-Stalinist interpretation of Marxism [Si 斯; 斯大林主義] along with the “Germano-Aryan” form of fascism [Ri 日; 日耳曼法西斯主義].’

— from Xu Zhangrun, ‘Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear’

trans. Geremie R. Barmé, ChinaFile, 10 February 2020

Thirty years earlier, Simon Leys (Pierre Ryckmans), art historian, essayist and Sinologue, had commented on the prospects for the rule of law in post-Mao China. His remarks were made in the context of how best to navigate a way through the maze of Communist Party rule and the tireless power struggles in Beijing:

‘… ingenuity and astuteness are not enough; one also needs a vast amount of experience. Communist Chinese politics are a lugubrious merry-go-round (as I have pointed out many times already), and in order to appreciate fully the déjà-vu quality of its latest convolutions, you would need to have watched it revolve for half a century. The main problem with many of our politicians and pundits is that their memories are too short, thus forever preventing them from putting events and personalities in a true historical perspective. For instance, when, in 1979, the “People’s Republic” began to revise its criminal law, there were good souls in the West who applauded this initiative, as they thought that it heralded China’s move toward a genuine rule of law. What they failed to note, however — and which should have provided a crucial hint regarding the actual nature and meaning of the move in question — was that the new law was being introduced by Peng Zhen, one of the most notorious butchers of the regime, a man who, thirty years earlier, had organised the ferocious mass accusations, lynchings and public executions of the land-reform programs.”

— from Simon Leys (1990)

in ‘Watching China Watching (II)’

China Heritage, 7 January 2018

With a lifetime of experience and an acuity honed over decades as a writer on and interlocutor with contemporary Chinese thought and culture, Jianying Zha is ideally suited to guide readers through the maze of the Xi Jinping era.

***

‘China’s Heart of Darkness’ was inspired by a lunchtime conversation at the Asia Society in New York on 13 November 2019. Kevin Rudd, former Australian prime minister and head of the Asia Society Policy Institute, had invited me to give a talk about the Chinese ‘anniversary year’ of 2019 (for the video of that talk and a Q&A session hosted by Orville Schell, see here). During my public remarks, I referred to Mao Zedong’s famous quip that he was ‘Marx plus Qin Shihuang’ 馬克思加秦始皇, and I quoted Xi Jinping’s observations about the Qin empire that had been published a month earlier on 2 October as part of the observances marking the seventieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. In them, Xi declared that through Party rectitude, ongoing anti-corruption purges and ceaseless political indoctrination, the People’s Republic could avoid the fate of all previous ruling entities in Chinese history. As a warning, Xi even quoted from the most famous poetic account of the destruction of Qin Shihuang’s Epang Palace, written by the Tang poet Du Mu (杜牧, 803-852) in the year 825 CE which ends with the lines:

The Rulers of Ch’in had not a moment

To lament their fate,

Those who came after

Lamented it.

When those who come after

Lament but do not learn,

Then they too will merely provide

Fresh cause for lamentation

From those who come after them.

秦人不暇自哀

而後人哀之

後人哀之

而不鑒之

亦使後人

而復哀後人也。

— from Du Mu ‘The Great Palace of Ch’in — a Rhapsody’

trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 25 February 2019

Xi declared that the Communists had ‘learned and would not lament’. He also returned to the topic of ‘the cycles of Chinese history’ — that millennia-long series of peasant-led rebellions that saw the overthrow of corrupt and unrighteous ruling houses, in the wake of which judicious rulers ushered in eras of stability and prosperity that in their turn, over time, became mired in the same corrupt ways that had undone their predecessors. Quoting Mao Zedong, Xi Jinping declared that equipped with Marxist-Leninist theory China’s Communists had broken free of this vicious cycle. Although, it was telling that he blamed the fall of the Qin empire not on the brutal Legalist thinking that had made the Qin a proto-totalitarian state, but rather on the sybaritic indulgence of the court.

[Note] For more on Xi’s 2 October 2019 essay and the ‘cycles of history’, see ‘The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud’ 獨夫之心 日益驕固, China Heritage, 10 March 2020

Contemporary independent writers in China also often refer to the Qin dynasty and its draconian rule as that ancient historical landscape, its tropes and policies, are not only relevant when talking about Mao, but have gained renewed importance in discussions of Xi Jinping’s own imperial ambitions and political overreach.

In his essays Xu Zhangrun has often referred to Xi Jinping as pursuing what he calls ‘rulership in the style of the Qin’ 秦制 Qín zhì. He too has quoted Du Mu’s famous poem ‘The Great Palace of Ch’in’ 阿房宮賦 although, unlike Xi Jinping, he asserted that the Communists have not learned from the murderous failures of their autocracy and that they are repeating the same mistakes that every purblind regime in Chinese history has made.

Writing shortly after the Beijing Massacre on 4 June 1989, Simon Leys noted that:

‘When Qin Shihuang, the founder of the first Chinese empire, died during a voyage in the provinces in 210 B.C., the members of his entourage were so afraid that the empire might immediately disintegrate that they did not dare to disclose the news of his death. Business was carried on as usual; but as it was summer, they loaded a cargo of rotting fish in the imperial chariot, to cover up the smell of the decaying body.’

— Simon Leys, ‘The Wrong March’

The New Republic, 19 June 1989

[Note] The original line in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian reads: ‘七月丙寅,始皇崩於沙丘平台。丞相斯為上崩在外,恐諸公子及天下有變,乃秘之,不發喪。… 會暑,上轀車臭,乃詔從官令車載一石鮑魚,以亂其臭。’

Not long after the demise of the first Qin emperor, ‘Emperor Second Generation’ 二世, Shihuang’s hapless son Huhai 胡亥 (this eighteenth son replaced the chosen successor, a more competent older brother, who had been executed) fell victim to plotting courtiers. Soon China’s first dynasty was overthrown by peasant rebels and the sumptuous Epang Palace was razed.

Leys ended his June 1989 essay with a question:

‘What amount of smelly luggage will be needed now to enable Chinese communism to continue much further on its aimless journey?’

The events of 1989, both in China and internationally, forced the Communists to change tack; all predictions of China’s imminent collapse have been confounded both by policy innovation and by the substantive transformation of the country’s economy and people’s livelihoods. As Jianying Zha observes in her powerful study of Xi Jinping, at the core of the odiferous juggernaut of the Communist Party a dark heart continues to beat.

***

***

During a lunchtime discussion following my Asia Society talk hosted by Kevin Rudd, Jianying mentioned that she had recently gone back to Hanfeizi and had even drafted an essay about the gloomy shadow the ancient Legalist thinker cast over Xi Jinping’s China. Having initially acquainted myself with Hanfeizi, Lord Shang and the Legalist tradition during my studies at Maoist universities in 1974-1976, I was intrigued. As a result of subsequent discussions at cafes in New York and via email and Skype after I returned to the Wairarapa in New Zealand, Jianying expanded on her original draft for publication in China Heritage.

An important body of material exists in both Chinese and European languages related to the pre-Qin Legalists and the rise of the Legalo-Confucian-Taoist (and later Buddhist) amalgam that exerted political and cultural power in the Chinese world for over two millennia. Academic purists may well disdain the everyday application of ancient ideas to contemporary politics; they may have even less time for those who attempt to see how power holders today evoke, manipulate and reinterpret the past.

In 1964, Mao Zedong used a pithy expression to express an ancient political practice: ‘make the past serve the present’ 古為今用 gǔ wéi jīn yòng. Scholars may like to think that Lord Shang, Han Fei and Dong Zhongshu, among others, are the exclusive preserve of refined scholarship, but statesmen, advisers and ambitious thinkers throughout Chinese history have proven that the power of the past is rarely merely academic.

The evocation and updating of tradition in modern China — that is, from the late-Qing era of the nineteenth century up to the present day — is a continuation of that age-old story. As ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’ demonstrates, it is also a constantly evolving reality. For those who would appreciate both the pull of the past and the forward thrust of the present, we encourage an approach grounded in New Sinology — a study of the Chinese world that takes the diverse literary, historical and intellectual traditions of the past, as well as the influences of Japan and the West, seriously.

***

The year 2021 will mark fifty years since Simon Leys dissected the nature of Maoist rule in his book The Chairman’s New Clothes (Les Habits neufs du président Mao). His forensic account of the Cultural Revolution written in the form of a diary, Leys revealed the skulduggery and the power plays at the heart of the Maoist enterprise. In early 2020, outspoken figures like the legal activist Xu Zhiyong and the former real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang used that same metaphor when they lambasted Xi Jinping as ‘an emperor with new clothes’.

In ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’, Jianying Zha trains her X-ray vision on the Chairman of Everything and offers a chilling report on what she can see.

— 22 July 2020

Wairarapa

New Zealand

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020