Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix LIX

本位

An innate tension within the Chinese party-state is that between top-down centralism and obsessive localism. From its inception in pre-revolutionary Russia, Communist Party organisation has been a cell-like structure that, while imposing directives from above, is often autonomous in its actions.

In China, Party leaders railed against the dangers of excessive ‘closed door-ism’ 關門主義 for nearly a century and, early on, Mao himself had warned of the dangers of ‘sectionalism ‘ 本位主義, placing one’s loyalty to one’s intimates, comrades and friends above the greater good.

Regardless, the party-state structure imposed on China from 1949 according to a Soviet model adjusted to local conditions, has been the norm. Despite attempts to adapt an often stifling managerial regime over the past decades, the Xi Jinping era has witnessed the reinvigoration of what, in the language of the internet, is called ‘the walled garden’, that is the control of the individual’s social participation and access to services by those who maintain the walls. Old walls have been refurbished and new walls have been constructed.

During the Zero-Covid era of 2021-2022, we noted the effect of China’s self-inflicted isolation and amped up internal ‘feudalism’ in A Country Besieged by Itself. In ‘Xi Jinping’s Silos — the corrosive individualism of collectives,’ Appendix LIX of our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we offer a recent essay on the subject published by Pekingnology. It discusses entrenched problems and attitudes that continue to operate under a new guise. Division, bureaucratic competition, jealously guarded access to privilege, power and material goods, have all long served the Communist Party’s core aims of command and control.

***

Pekingology is a substack newsletter edited by Zichen Wang, a former Xinhua journalist who works for the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), a Beijing think tank. Wang also edits The East is Read and CCG Update.

Officially tolerated quasi-independent publications like Pekingnology are part of the ‘grey information economy’ that flourishes within what, since the 1980s, we have called China’s ‘velvet prison’. For more on this topic, see Less Velvet, More Prison and Elephants & Anacondas.

Participants in the grey information economy, be they academics, policy wonks, journalists or freelance commentators partake of a hallowed tradition in which canny authors ‘write between the lines’. Theirs is a well-honed art that enables writers of all kinds to communicate uncomfortable truths within the boundaries of permitted speech. The adept can utilise their authorial dexterity to identify issues of pressing concern, skirt around the systemic origin of problems without challenging the system itself and even offer palliative advice and partial cures to egregious problems. An ancient art honed to perfection under the party-state, it is often referred to as ‘hitting line-balls’ 打擦邊球. Practitioners are, to use a short-hand, expert at ‘pointing at the mulberry while vilifying the locust’ 指桑罵槐. Other well-worn clichés also reflect this well-practiced technique of seeking the solace of self-expression within a repressive environment. They include:

拐彎抹角 、含沙射影 、借題發揮 、

隱晦曲折 、旁敲側擊 、指雞罵狗。

Lü Dewen’s essay on Xi Jinping’s silos is an example of such writing. The typographical style of the translation, including passages in bold font, has been retained. The highlighted passages offer a further layer of ‘wink-wink-nod-nod’ critical commentary on the status quo by Zichen Wang, editor of Pekingnology.

Lü Dewen’s commentary is in the style of what is known as 小罵大幫忙 ‘a minor criticism that ultimately bolsters the status quo’. Both Professor Lü and Zichen Wang know that the Party is not daunted by silos, rather it is fearful of those who venture to cross boundaries and dare to create communities of shared interest.

The Hungarian writer Miklós Haraszti summed up this state of affairs decades ago:

Communication between the lines already dominates our directed culture. This technique is not the speciality of the artist only. Bureaucrats, too, speak between the lines: they, too, apply self-censorship. Even the most loyal subject must wear bifocals to read between the lines: this is in fact the only way to decipher the real structure of our culture… .

The reader must not think that we detest the perversity of this hidden public life and that we participate in it because we are forced to. On the contrary, the technique of writing between the lines is, for us, identical with artistic technique. It is a part of our skill and a test of our professionalism. Even the prestige accorded to us by officialdom is partly predicated on our talent for talking between the lines… .

…Debates between the lines are an acceptable launching ground for trial balloons, a laboratory of consensus, a chamber for the expression of manageable new interests, an archive of weather reports. The opinions expressed there are not alien to the state but are perhaps simply premature. (Quoted in Less Velvet, More Prison.)

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

8 January 2023

Xi Jinping’s Silos

Below is a translation of 呂德文:孤島效應是一大公害,是社會衰敗的徵兆 Lü Dewen: The silo effect is a major public harm and a sign of societal degeneration, posted on January 3 in the 新鄉土 New Rural WeChat blog of the China Rural Governance Studies Center of Wuhan University 武漢大學中國鄉村治理研究中心.

Lü Dewen is a Professor at the School of Sociology, Wuhan University, and has agreed to this translation and publication. The emphasis is all mine.

***

Suffocating Silos and Social Stagnation

Lü Dewen

Today, Chinese society has fallen into a state of fragmentation. Everyone is self-protective and wary, with each group and unit focused on creating a safe and comfortable environment for themselves, completely disregarding the troubles they are causing for others. This “silo effect” has become a significant public harm, increasing the cost of social operations and weakening the public sphere, signaling a degeneration in society.

***

***

Part I

Starting January 1, 2024, Peking University and Tsinghua University will share identity verification information to facilitate smooth inter-campus movement for their staff and students.

At first glance, this might seem like a story about “openness,” but on closer examination, it reveals an expanded version of “closure.” Clearly, the interconnectivity of Tsinghua and Peking University staff and students is an act of self-fragmentation from the city and society at large. This policy, while convenient for the two universities, burdens the rest of society. It declares to the society that Tsinghua belongs to Peking University people and vice versa, but neither belongs to the society as a whole.

China’s top two elite universities, proud of their inclusive culture, have paradoxically become insular, leading the way in establishing “enclosures” and creating societal silos, which is disheartening. Perhaps, the definition of an elite university needs rethinking. Following the business logic, the more a university emphasizes “exclusivity,” “privacy,” VIP status, and superiority, the more elite it appears. The elite status of universities is not measured by their contributions to society, but rather by their mystique and the privileged status of their faculty and students.

Following the example of Tsinghua and Peking University, a considerable number of universities across the country are becoming silos. The justifications for this fragmentation are laughable, claiming that open campuses disrupt order and pose risks of student injuries. These reasons are an insult to universities and intellectuals and a disgrace to the dignity of university students.

Professors who consider themselves “owners” of the university and advocate for closed campuses are contemptible. Students who view themselves as children and think closed campuses are protective are disappointing. University leaders, who disregard the value of public service and reduce their role to mere security concerns, are short-sighted.

There was a time when cities strived to improve micro-circulation for better connectivity. Now, such plans have stalled, and even the discussion of implementing them has ceased. The higher the state ranking of an institution, the more difficult it is to negotiate passage through campuses, hospitals, or institutional compounds. During the COVID-19 pandemic, cities primarily requisitioned universities, party schools, and other units within their jurisdiction, as coordination with province-run and central ministry-run universities was daunting.

It’s not surprising that many universities have become isolated kingdoms, indifferent to the needs of the cities they are in and the voices of the citizens.

Part II

Not only universities but also other places have set up barriers to movement. Everywhere you go, there are barriers, walls, QR code scanning, registrations, appointments, facial recognition, and checks.

The issue of “security” has moved from the hidden corners of society into broad daylight. Previously, security was the responsibility of specialized agencies and professionals. Now, everyone is the primary person responsible for security. Even the smallest units must appoint security officers, covering property safety, fire safety, and personnel safety. To prevent any possible incident, extreme caution is required.

As a result, security procedures and equipment have become commonplace in every setting. Local governments have invested an enormous amount of human and financial resources in everyday security, yet the more they invest, the less capable people seem to be of handling risks. When everyone feels endangered, everyone becomes defensive.

Currently, almost every residential area is a silo. The government has taken emergency measures as a norm, and 网格管理 “grid management” has almost become an unquestionable innovative approach. No one seems to have considered the consequences of dividing areas into “grids” and assigning responsibilities to “grid managers”. In fact, this creates territorial divisions and fosters an attitude of indifference towards others’ affairs.

No one seems to have thought about how, after breaking free from feudal constraints and striving for interconnectedness, a unified market through reforms, and a Community of Common Destiny, we are now creating obstacles and differences between people on a micro level.

In fact, freedom is not just an abstract slogan. Nowadays, the difference in status between people can be measured by their ability to cross these “boundaries.” University staff and students form a special interest group, exclusively enjoying public cultural spaces, leaving ordinary citizens who yearn for an academic atmosphere frustrated. If they cannot resist, they have to rely on connections with university staff for appointments, making relationships a symbol of status.

It’s ironic that on one hand, public spaces in cities are becoming more open, with parks, libraries, museums, and even community centers setting up stations for outdoor workers. Some shops even offer cheap or free services to cleaners. On the other hand, those with vested interests are monopolizing territories, erecting fences, and setting thresholds, taking advantage of the city while guarding their small plots.

Part III

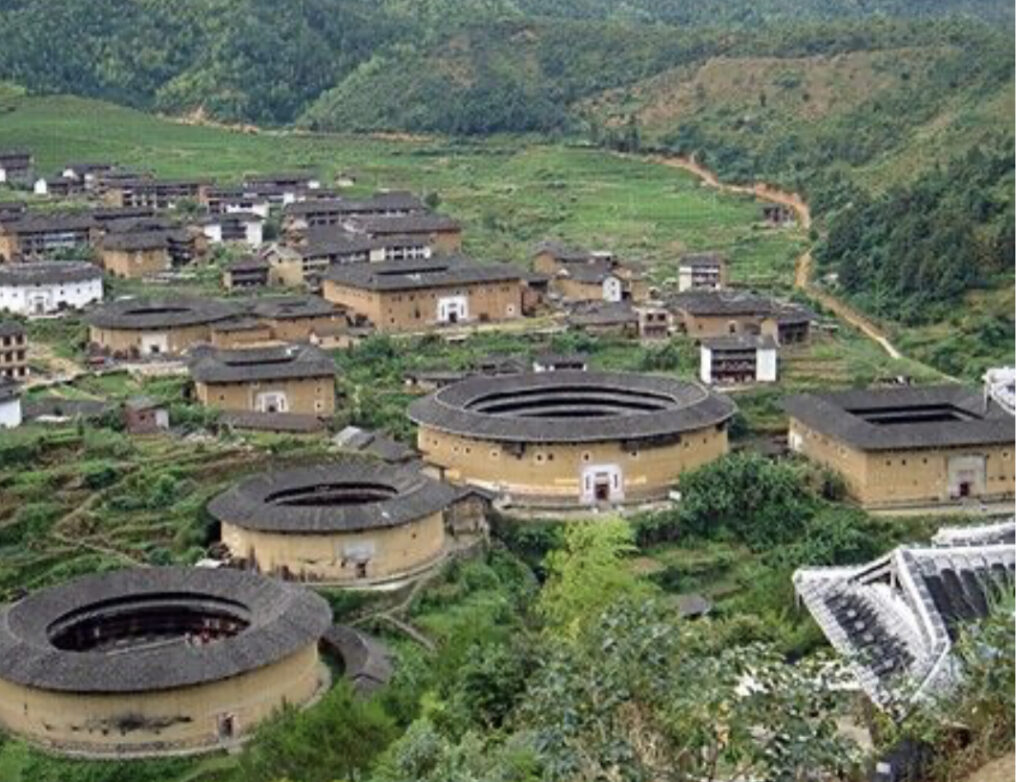

We are deliberately creating 土围子 “enclosures.”

There was a time when “enclosures” symbolized feudalism. As a Hakka, living in clustered family settlements, our ancestral homes were fortified for defense, with gun holes for protection. As a child, I had a strong sense of territory, and visiting classmates from different families required caution, as passing through others’ territories attracted scrutiny.

***

***

People are aware of the warmth within these “enclosures” but choose to ignore the cold brutality between them. Many imagine the social integration role of “village elders” but overlook that they often represent specific territorial interests and are leaders in territorial conflicts, contributing to social division.

The collective economy of the Pearl River Delta, once envied due to rapid industrialization and urbanization, increased land values dramatically. Some village groups saw their collective income skyrocket, leading to enormous dividends and overnight wealth from demolitions. Members within these “enclosures” benefited, but those outside were envious. This collective economy raises doubts about whether it is socialist or feudal in nature.

Whether it’s the “grid system” in urban communities or the “collectivization” in rural areas, both appear modern, even socialist. Initially, these systems aimed to promote social progress and openness. However, they inadvertently created the “silo effect.” People live in fortresses with clear boundaries, calculating personal gains and losses.

The “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) effect continues to spread. Cities need rubbish collection sites – but not near anyone’s neighborhood. Trash bins are necessary – but not under anyone’s building. Everyone fights for their rights but ignores public good.

Part IV

The silo effect has become institutionalized. Everywhere there are “enclosures,” boundaries, and each government department is staking out its territory.

At the grassroots level, local authorities have been “colonized” by higher levels, losing their autonomy and ability to make decisions. Each department wants a “foot soldier” at the grassroots level, commanding or bypassing local authorities as needed.

Wealthy departments spend money expanding their influence through the establishment of grassroots organizations. In less favorable circumstances, they hire coordinators to work for their interests. Meanwhile, powerful departments leverage tools such as supervision and performance assessments, mandating that grassroots entities serve their departmental agendas. Grassroots levels are inundated with staff from various sectors, who, despite being based locally, primarily execute tasks delegated by higher authorities, adhering directly to their commands. Within various platforms and systems, these workers are governed by protocols, functioning in a regimented manner, effectively becoming “screen bureaucrats.”

There is a pronounced silo effect between departments. Each department operates with its own interests in mind, working from its own perspective. In conducting their activities, many departments naturally adhere to the principle of pursuing benefits and avoiding disadvantages. They strive to retain control over advantageous matters, while actively seeking to offload tasks that are burdensome and yield little appreciation.

Departments also have a hierarchy, with powerful ones reaping benefits and weak ones struggling to survive, relying on hard work to gain favor from leaders. Due to departmental selfishness, even basic information is not shared.

A typical example is each department building its system and platform, unwilling to share information, creating data silos. Frankly, the construction of so-called big data platforms by local governments is unlikely to succeed under the current system.

Before the commercialization of ride-hailing services, transportation departments and taxi companies were building their respective platforms, with no technical barriers but facing departmental and regional divisions. The smaller the platform’s user base, the less efficient and useful it becomes.

指尖上的形式主義 “Formalism at the fingertips” stems not from technology but from departmental fragmentation.

[Zichen’s note: “Formalism at the fingertips” refers to excessive formalities and duplication across government apps and social media, such as dozens of WeChat groups for work projects within one unit that needed to be checked in every day, or a certain time that must be spent within a certain app.

“Formalism at the fingertips” represents a mutated and renewed form of formalism in the digital context and is one of the primary causes of increased burdens at the grassroots level. Combating “Formalism at the fingertips” is crucial for the image of the Communist Party of China, for winning the hearts and minds of the people, and for the modernization of the state governance system and capabilities. It holds significant importance for promoting a positive social atmosphere in the Party and government conduct. To implement the decisions and arrangements of the Party Central Committee and fulfill the Central-level requirements for rectifying formalism to reduce burdens at the grassroots, specific suggestions are proposed for standardizing the management of government mobile internet applications (hereinafter referred to as government applications), government’s public accounts, and chat groups.

— Concerning Several Opinions on Preventing and Controlling “Formalism at the fingertips” by Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission]

Due to the troubles caused by this fragmentation, various coordination mechanisms have been established. More and more leadership groups and committees are formed, but this leads to another problem: government inefficiency due to overlapping roles. Departmental leaders attend more meetings, partly due to the increase in coordination bodies.

At the grassroots level, the establishment of emergency bureaus aimed to integrate emergency resources, but emergency coordination is a comprehensive task that no single department can manage. Ultimately, government offices must coordinate. In some places, to improve efficiency, personnel are reassigned from various departments to focus on key tasks. In some cases, these task forces have become special zones, attracting the most capable and energetic young officials, and inadvertently restructuring the grassroots system.

A multi-centered work pattern has emerged at the local level, often relying on unconventional systems. With concentrated governance resources and leadership attention, the result is a few active individuals and many who are disengaged.

Regrettably, overall societal efficiency is likely declining. While we see the efficiency of concentrating efforts on major tasks, we overlook the sharp decline in regular capabilities due to the silo effect.

***

Source:

- Zichen Wang, Wuhan University professor blasts security- and selfishness-driven fragmentation, where “even basic information is not shared”, Pekingology, 8 January 2023, a translation of text published in the 新鄉土 New Rural WeChat blog of the China Rural Governance Studies Center of Wuhan University 武漢大學中國鄉村治理研究中心

***

***

Chinese Text

孤島效應是一大公害,是社會衰敗的徵兆

呂德文/武漢大學社會學院教授

今天,中國社會陷入了孤島之中,人人自保、事事防備,每個群體以及每個單位都在創造安全舒適的生存環境,全然不顧他們同時在給別人製造麻煩。孤島效應已經成為一大公害,它提高了社會運行成本,減弱了公共性,是社會衰退的徵兆。

一

從2024年1月1日起,北大清華將交互身份核驗信息,兩校師生實現暢行互通。第一眼看,這似乎是關於「開放」的故事,但看第二眼,卻發現這是一個擴大版的「封閉」的故事。很顯然,清華北大師生互通的背後,其實是自絕於城市,自絕於社會。這一政策,方便了兩校師生,卻麻煩了全社會。

它向全社會宣示:清華是北大人的清華,北大是清華人的北大,但清華北大不屬於全社會。

中國最頂尖的兩所精英大學,以「兼容並包」文化自傲的學校,卻固步自封,帶頭建立「土圍子」,人為設置社會孤島,讓人汗顏。也許,精英大學需要重新定義了,可以比照商業邏輯,越是標榜「私享」、「私密」、VIP、獨尊,就越是精英。高校的精英地位,不在於其對社會的貢獻,而在於其神秘感,師生的尊貴身份。

比照清華北大,如今全國有相當部分高校,都在孤島化。孤島化的理由簡直讓人苦笑不得,說是開放校園會影響校園秩序,萬一學生受傷了怎麼辦?這種理由,簡直是對大學和知識分子的侮辱,是對大學生的人格的侮辱。

教授把自己當成大學的「業主」,為封閉校園叫好,讓人鄙視。大學生把自己當小孩,以為封閉校園是在保護自己,讓人遺憾。大學的領導者無視公共性價值追求,校長思維降低為保安思維,考慮的不是如何服務社會,而是自身「安全」,極其短視。

曾有一段時間,各大城市都在致力於打通微循環,讓城市更暢通。現如今,這種計劃似乎停頓了,議題設置都沒了,更不要說執行。市政公路要經過校園、醫院、單位大院,談何容易。越是層級高的單位,越是難以溝通,越是面臨討價還價。疫情防控期間,各城市首先徵用的是市屬高校、黨校和其他單位,省屬、部屬高校的協調讓人望而生畏。

這也就不難理解,很多高校成了獨立王國,完全不顧及所在城市的需要,市民的呼聲。

二

何止大學是孤島,是個地方都要設置一些通行障礙。到處都有欄桿,到處都有圍牆,到處都要掃碼,到處都要登記,到處都要預約,到處都要人臉識別,到處都要檢查。

「安全」問題已經從社會的隱蔽角落走入了光天化日之下。過去,「安全」是屬於專門機關,專業人士的職責,現如今,人人都是安全的第一責任人。再小一個單位,也要設置安全員,財產安全、消防安全、人身安全,無所不包。為了預防萬一,就得一萬個小心。

因此,任何場合都要安全程序,都要設置安全設施,也就變得理所當然。各地為了個日常「安全」,不知投入了多少人力和財力,效果卻是,投入越大,人們承受風險的能力越差。人人自危,那就人人防備。

當前,幾乎每一個小區都是孤島。現如今,政府把特殊時期的無奈之舉,當成是一個常態,網格化管理幾乎成了無可置疑的創新舉措。就沒有人仔細去想想,劃分網格,劃清界限的背後,賦予每個網格員職責以後,其實是在劃分「領地」,製造事不關己的社會風氣。

就沒人去想想,我們費盡心機打破封建繩索,節衣縮食讓各地互聯互通,深化改革創造統一大市場格局,竭盡全力構建命運共同體,結果卻在微觀環境里,不斷製造障礙,不斷製造人與人之間的差別。

事實上,自由並不是一個抽象口號。現如今,人與人之間的身份差別,完全可以從能否突破「界限」來衡量。大學師生是特殊利益群體,他們獨享公共文化空間,讓想要沾染學術氣氛的普通市民望梅止渴。實在止不住,就只能托關係讓學校的老師幫忙預約,結果,關係也成了身份象徵。

讓人感慨的是,一方面,城市裡的公共空間越來越開放,公園、圖書館、博物館等,都在開放。乃至於,很多居委會都為戶外工作者設置了驛站。有些街邊小店專門為清潔工提供廉價或免費服務。但在另一方面,既得利益者卻在獨佔領地,不斷打圍欄設門檻,既要佔城市的便宜,又要守著自己的一畝三分地。

三

如今,我們在刻意製造一個個「土圍子」。

曾幾何時,「土圍子」是封建制的象徵。筆者是客家人,聚族而居,老家每一個土樓都帶有軍事功能,我老家祖屋現如今都還有槍眼,方便防衛。筆者小時候還有極強的「領地」概念,去外姓同學家裡玩,得小心翼翼,路過別人的「領地」,可以感受到別人審視的眼光。

人們只知道「土圍子」裡面的溫情脈脈,卻選擇性忽視「土圍子」之間的冷血殘暴。很多人在想象「鄉賢」的社會整合功能,卻選擇性忽略「鄉賢」通常代表特定的「領地」利益,他們同時也是「領地」之間鬥爭的領導者,是社會分裂的助推手。

珠三角地區的集體經濟,曾一度讓人羨慕。受益於工業化和城鎮化,當地的土地增值極快。有些村民小組(自然村)集體收入暴增,村民因此獲得巨額分紅,一旦拆遷,村民一夜暴富。「土圍子」以內的集體經濟成員,享受好處;站在「土圍子」之外的人,則紅了眼。這種集體經濟,到底是社會主義性質的,還是封建性質的,很值得懷疑。

城市社區的「網格化」也好,農村地區的「集體化」也罷,看上去都是現代性的產物,甚至還具有強烈的社會主義色彩。在本意上,這些制度都是為了增進社會進步,讓社會更加開放平等。然而,它們都意外製造了社會「孤島」效應。人們都生活在堡壘里,都有明確的邊界意識,都躲在堡壘里計算個人利害得失。

至今為止,鄰避效應還在擴散。城市垃圾站是要修的,但別修在自己小區旁邊。小區里的垃圾桶是要有地方放的,但別規劃在自己樓下。業委會是要有的,但誰當誰倒霉。人人都在義正嚴辭伸張權益,唯獨不講公義。

四

社會孤島效應也體制化了。社會上到處都是「土圍子」,划定界限,政府部門也在跑馬圈地,建立自己的專屬「領地」。

現如今,基層已經被上級部門「殖民」了,他們沒有自主性,能夠做主的事情越來越少。每個部門都希望自己在基層有個「腿」,能夠一竿子插到底。所以,各部門都有強大的動力指揮基層,或者繞開基層。

有錢的部門出錢,通過擴大機構建立基層組織,再不濟也要雇傭協管員,為自己乾活。有權的部門,則通過監督考核等槓桿,要求基層為自己的部門服務。基層充斥著各種條線工作人員,他們人在基層,做的卻是上級部門下派的任務,直接接受上級指令。在各種平台和系統中,這些工作人員被程序控制,按部就班工作,成了「屏幕官僚」。

部門之間有明顯的孤島效應。每個部門都有自己的利益,都站在自己的角度開展工作。很多部門在開展工作時,趨利避害是不言自明的原則。有利的事情,一定要想方設法攥在手裡;吃力不討好的事情,則要想方設法推出去。

部門之間也講究三六九等,強勢部門好處佔盡,年中考核一定要優;弱勢部門則自認倒霉,夾縫中生存,只能靠努力工作獲得主要領導青睞。由於每個部門都有小九九,都在想方設法防備別的部門,以至於最為基礎的信息也不願意共享。

最典型的表現是,每個部門都建立自己的系統和平台,都不願意和別的部門共享信息,部門間的孤島效應擴散到信息領域,製造了數據孤島。不客氣地說,各地政府花大精力建立所謂的大數據平台,在現有的條塊關係下,根本就不可能成功。

在網約車商業化之前,各地的運管部門和出租車公司都在建立自己的網約車和電話約車平台,技術上沒有門檻,但問題出現在部門和地區分割上。平台使用規模越小,數據越不能共通,效率就越低,就越無用。

所謂「指尖上的形式主義」,根源不在於技術,而在於部門之間的孤島效應。

由於孤島效應太麻煩,各地也就不得不成立各種協調機制。各種領導小組、委員會越建越多,但出現了另一個問題:政府機構疊床架屋,效率不進反退。各部門領導開會越來越多,其中一個重要原因就是因為各種協調機構越來越多。

在基層,組建應急局的本意是為了更好地整合應急力量,把應急委員會設置在應急局也看似理所當然,但應急是一項綜合協調極強的工作,一個職能部門根本就不可能調動指揮其他部門。最終,還是得依靠政府辦來協調。

很多地方為了提高效率,在短時間內推進某項重點工作,乾脆從各部門抽調人員,組成指揮部集中攻關。有些地方,抽單幹部的比例極高,甚至於,指揮部成了特區,最有能力也最有活力的年輕幹部可能都到了這種攻堅克難的部門,這在無形中重構了基層體制。

地方工作出現了多中心工作格局,常規體制往往不在發揮作用,而一直依賴於非常規體制。基層出現了奇妙的現象,治理資源越來越集中,領導注意力越來越聚焦,其結果一定是少部分人積極,多數人躺平。

非常遺憾的是,社會整體效率很可能在下降。我們看到了集中力量辦大事的高效,卻忽略了孤島效應下常規能力的急劇下降。

***

Source:

- 吕德文,孤島效應是一大公害,是社會衰敗的徵兆,微信,2023年1月3日