Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix IX

蛻

During my first trip to New York in the northern autumn of 1986, my then-partner Linda Jaivin and I picked up a copy of Hans Askenasy’s Are We All Nazis? at Strand Bookstore, just south of Union Square. The book was related to the Milgram experiments conducted by the psychologist Stanley Milgram at Yale University in the 1960s, the findings of which had caused something of a sensation when they were published in 1974 (see Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View).

The Milgram experiments measured the willingness of participants to obey the orders of an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their beliefs or conscience. As a follow up study observed, ‘Participants were led to believe that they were assisting an unrelated experiment, in which they had to administer electric shocks to a “learner”. These fake electric shocks gradually increased to levels that would have been fatal had they been real.’ (see Thomas Blass, ‘The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: Some things we now know about obedience to authority’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1999, 29 (5): 955–978). The Stanford prison experiment of 1971 attempted to expand the parameters of the investigation, but it was soon mired in controversy.

Although Are We All Nazis? was sensationalistic and its style scrappy, the book struck a chord. For most of the previous decade I had lived, studied and worked in Mainland China and Hong Kong. During that time I encountered survivors both from the Mao-Liu years (1949-1966) and High Maoism (1966-1976) and in their personal stories and through written accounts I learned a deal great about the topic of Askenasy’s book. It reaffirmed many things that, during my teens in Sydney, Australia, my German-Jewish grandmother had told about das Hitlerzeit (see Beijing, 1st July 2021 — ‘It was a sunny day and the trees were green…’, China Heritage, 1 July 2021).

This Appendix to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium features ‘Who Goes Nazi?’, an essay by the noted journalist and broadcaster Dorothy Thompson (1893-1961) that appeared in the August 1941 issue of Harper’s Magazine. It is prefaced by a personal reflection and excerpts from ‘The Dilemma of the Liberal’, published by Thompson in 1937. It is followed by a note on the Rorschach Tests for Nazi war criminals, a link to a parody by Randy Rainbow and an account of how Dorothy Thompson came to be cancelled avant la lettre.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

12 April 2022

***

Contents

The material in this Appendix is divided into the following sections (click on the title section to scroll down):

***

Related Material:

- Jeremy Goldkorn, ‘Ugh, here we are — Q&A with Geremie Barmé’, SupChina, 8 April 2022

- We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again, China Heritage, 31 March 2022

- Karine Walther, ‘Dorothy Thompson and American Zionism’, Diplomatic History, vol.46, no.2 (2022): 263-291

- Spectres & Souls: vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021 — China Heritage Annual 2021

- Something In The Air, China Heritage, 8 June 2018

- Damion Searls, The Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and the Power of Seeing, Crown, 2017

- The Silencing of Dorothy Thompson (trailer), YouTube, 13 November 2013

- Peter Kurth, interview #1 (transcript), The Silencing of Dorothy Thompson, 13 July 2013

- Nick Joyce, ‘In search of the Nazi personality: The Nazi Rorschach responses have captured psychologists’ imaginations for decades’, American Psychological Association, vol.40, no.3 (March 2009)

- Chris Hedges, American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America, Free Press, 2007

- Clive James, ‘Hitler’s Unwitting Exculpator’, on Hitler’s Willing Executioners by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Alfred A. Knopf (a shorter version of this review-essay first appeared in the New Yorker, 22 April, 1996); and Clive James, ‘Postscript to Goldhagen’, 2001

- Victor Klemperer, I Will Bear Witness, 1933-1941: a Diary of the Nazi Years, trans. Martin Chalmers, New York: Random House, 1998

- E.A. Zillmer, M. Harrower, B.A. Ritzler & R.P. Archer, The quest for the Nazi personality: A psychological investigation of Nazi war criminals, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995

- Peter Kurth, American Cassandra: The Life of Dorothy Thompson, Little Brown & Co., 1990 [China Heritage was unable to obtain a copy of this text.]

Mini Maos

Geremie R. Barmé

It was early morning on my first day in Beijing in October 1974. All of the loudspeakers in our dorm building were blaring out the news broadcast by Central People’s Radio in a shotgun-harsh staccato at a seemingly impossible speed. As I was brushing my teeth a gruff voice barked over the cement trough between us:

偷听敌台! Tōutīng dítái!

‘Enemy Broadcast!’ The voice belonged to a strikingly handsome Worker Peasant Soldier Study Officer 工农兵学员 (the Maoist term for ‘student’) who was wearing, even at that darkling hour, a high-collar blue Mao jacket. Steely faced, his tone was both a warning and an accusation. I had no idea that he’d just said: ‘You’re furtively listening to an enemy radio station!’

He followed it up with another bark:

苏修广播! Sūxiū guǎngbō!

‘That’s Soviet Revisionist radio!’

Along with taking note of some new vocabulary, I was suddenly reminded of the stories of my grandmother and father. In 1970, around the age of sixteen, I had become interested in part of our family history; I learned some German and got to discussing the past with my grandmother. My interest was in part piqued by our high-school modern history course which required that we read an anthology of documents and newspaper articles about Germany from WWI to Kristallnacht in 1938. In parallel, my interest in China and the Cultural Revolution, which had been sparked some years earlier by a high-school classmate, grew in intensity along with my fascination with modern history. My grandmother, an energetic reader of history and novels about the past, began sharing details of their life during what she always referred to as die Hitlerzeit. (For more on this, see Beijing, 1st July 2021 — ‘It was a sunny day and the trees were green…’, China Heritage, 1 July 2021)

My father and Omi had described how, over time, once-friendly neighbours suddenly shunned them, classmates turned their backs and businesses denied them service. It was a slow, painful and dispiriting process that ate away at the family until they finally left in the late 1930s. (See Victor Klemperer’s extraordinary record of this period in I Will Bear Witness, 1933-1941: a Diary of the Nazi Years, 1998.) ‘Aryan’ friends helped facilitate their departure and, soon after the war, those old contacts resumed. From the 1950s, my father made regular business trips to Germany and in my teens he would entertain us with bitter stories about some of the ex-Nazis he encountered on his travels and the barbed exchanges he had with them. A man of punctilious manners, my father made no attempt to conceal his contempt and ire during such encounters. I let them know, he told me, that I knew who they were, just as I knew that they knew what I was. He joked that he could tell an ex-Nazi at ten paces.

I thought of those stories when my stern classmate berated me on that October morning and, from then on, as I met dozens of other former Red Guards, I would wonder just what they had done during the violent early years of the Cultural Revolution. In Beijing, the evidence of the chaos was evident — bullet-holed walls at the nearby campus of Tsinghua University; shuttered buildings; signs that had been painted over; and huge slogan walls and panels disguising a landscape pockmarked by lacunae.

Other types I encountered during my first days in Beijing included the stern Party cadres and humourless teachers in charge of us, robotic workers in the student cafeteria; as well as a raffish joker who wore a bomber jacket. His father was a muckety-muck in the Beijing Military Region and it was my first encounter with the alternate reality of Communist Party rule. There was also the tall, square-jawed former worker who was softly spoken and kind and his roommate, a paunchy young cadre who gave Mao’s poetry in traditional binding. He taught me a few of the poems and shared harmless jokes. Then there were the more-revolutionary-than-thou Canadians of China descent. They were the offspring of ‘red capitalists’ and one of their number, who dressed like a Red Guard and wore ponytails, was quick to offer me a finger-wagging lecture on the fact that due to her lineage and ethnicity she ‘got’ the revolution intuitively. Caucasians like me would simply never understand the Chinese revolution nor, for that matter, China. It simply wasn’t in my genes.

I came to think of many, although not all, of them, both men and women as ‘Mini Maos’. As I learned more about Mao Zedong Thought in theory and in what passed for revolutionary practice, as well as gaining a deeper appreciation of the Cultural Revolution, the ‘Mini Mao’ personality type revealed itself. Mercurial, boastful, hectoring, rigid, yet also adept at sudden volte faces, the wannabe Mao’s had been trained both by official fiat and through the crucible of purge politics. Many of those who made it to Maoist universities were not simply toadies or survivors of struggles, they were uniquely adapted to the Mao era. Homo Xinesis, the subject of our discussion of the ‘new socialist person’ or Sino-Homo Sovieticus in the Xi Jinping decade, is direct heir to the Mini Mao psychology inculcated by High Maoism, itself a continuation of the Mao-Liu-Deng seventeen years of 1949 to 1966 (for more on this topic, see (see ‘Homo Xinensis’, ‘Homo Xinensis Ascendant’, ‘Homo Xinensis Militant’).

During those years I would often wonder what my classmates in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenyang had got up to during the most violent phase of the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1967, as well as during the pitiless ‘Lin Biao interregnum’ of 1967-1971. What had they done since and what did they have to do to secure one of the prized positions as a student in a late-Maoist university?

Following Mao’s death it was impossible to avoid these questions as people with blood on their hands were everywhere. When visiting Beijing from 1977 up to the late 1980s, I would generally stay with friends at the Foreign Languages Press at Baiwanzhuang, not far from Xizhimen. My hosts were discreet, but their fellow editors and translators, a number of whom befriended me, were far less reticent. In the late 1970s, they readily pointed out colleagues who had been involved in attacks on their former friends and, during both public struggle sessions and denunciations, and more often under the cover of night, would gang up on ‘suspects’, many of whom died as a result.

I also heard how some ‘radicals’ at the Press perfected ways to kill their victims in such a way as to avoid detection; then there were those who simply dragged their enemies to the top of the building where they ‘committed suicide’. For all of the sedate appearances of the Press and Beijing generally during those years, memories of Red August 1966, not to mention the betrayals, backstabbing and violence of the years thereafter were still raw and, for those few years, many people I met were desperate to share their long pent-up anguish, not to mention their outrage at being forced to share an office, the canteen, and even dormitories with killers who enjoyed freedom as a result of Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 exhortation to ‘unite as one in looking to the future’.

The bitter accounts of psychically wounded friends and acquaintances brought to mind the stories my grandmother had told me about life in 1930s’ Cologne. They have since been bundled together and they came to mind again when I read Dorothy Thompson’s 1941 essay ‘Who Goes Nazi?’

Dorothy Thompson &

The Convulsive Embrace of History

‘Dorothy Thompson was for a period of about 20 or 30 years the leading woman journalist in the world, I would say, in the 1920s 30s and 40s. She was American of English extraction, but she was born in America, and her career was noted mainly for her opposition to fascism and to authoritarian government wherever she saw it. She was married three times. She was married to Sinclair Lewis … [who] won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1930. She was a fearless reporter, writer, columnist. She had a column 3 times a week in the New York Herald Tribune that was syndicated worldwide. She was the highest paid lecturer in the United States. It goes on. Time magazine put her on the cover in 1939 and said that apart from Eleanor Roosevelt she was the most influential woman in the United States. Dorothy Thompson was the most influential woman journalist of her time in the 1920s 30s and 40s. She was the voice of public outrage against fascism wherever she saw it around the world. …

‘Dorothy Thompson was the first journalist of note to be expelled formally by Hitler from Germany in 1934. She had been a relentless critic of the Nazis from the day she first heard of them. … [F]ascism was an evolving concept for everyone at that time, certainly for her readers in America and England no one really knew what fascism was if they thought of it at all they thought of Mussolini in those days. Hitler she regarded as … more than a fascist but in fact as a psychopath and she could not believe that the German people, of whom she was very fond through her experiences in Germany, would in fact surrender all of their rights to the Nazi party under Hitler. She could not believe this would happen. In fact most people didn’t believe it would happen. She saw it coming though, and she started warning about it very early on. She started writing about it too … . She believed Hitler when he said that the Jews should be removed from the scene. She was one of very few journalists who said, “You know, he means this. He’s not just talking about this to get votes. This really is what he intends to do,” and she was not heeded. She was made fun of for her German obsession in the early 30s but she wrote so resolutely against the Nazis and she did publish a perfectly brilliant satiric interview with Hitler right after she had finally met him. And she came to Germany again in 1934 right after the so-called Night of Long Knives, the first of the Nazi massive purges after Hitler came to power, and she was there to cover the scene as she saw it and she was presented with expulsion papers by the Gestapo and told that she had 24 hours to leave the country. This was a very big news item at the time. She was not just famous in her own right by then as a journalist but she was married to Sinclair Lewis and so she was Mrs. Sinclair Lewis being expelled from Germany by the Nazis. From the moment they came to power, she was their most voracious critic, to the point of the Nazis actually established something called the Dorothy Thompson emergency squad in Berlin whose job it was to monitor whatever she wrote and said about them worldwide. Hitler got crazy when you talked about Dorothy Thompson. Goebbels got crazy. They couldn’t stand that a woman, of all things, was such a strong opponent to their regime and their philosophy, such as it was. She regarded their philosophy as a hodgepodge of racist nonsense and pagan wishful thinking but the apparatus of Nazi state was such that it knew how to control the government in a bureaucratic sense and a military sense. So to her horror the pagan philosophy, the pagan racist exalted homoerotic philosophy, as she saw it, won the day and she was their chief enemy. She was considered by most people to be the chief and leading voice against the Nazis in the West.’

— Peter Kurth, interview #1, The Silencing of Dorothy Thompson, 13 July 2013

***

***

The Dilemma of the Liberal

Adam Tooze

“The consciousness that I live in a revolutionary world is the central fact in my life. I go to sleep and I awake thinking of the world in which I live. My whole personal life has become in a profound sense of secondary importance, and indeed, it, so immediate and so practical, is the part which is dream-like and unreal, and the other, more remote, touching me personally so little, is the imminent, the overwhelming reality. At the center of what I know is the realization and the acceptance of the certainty that never in my lifetime will I live again in the world in which I was born and grew to maturity.”

These words were written by Dorothy Thompson in January 1937 in an essay titled, “The Dilemma of the Liberal” published in Story magazine.

This life which you lead, a voice says to me continually, is in the deepest sense senseless; a repetition of social gestures, somehow hollow; it ties to nothing, it is part of nothing. It is a dream, and the reality lies elsewhere … this nucleus, myself, my husband, my child, the people dependent on us and our friends, should somehow tie up and be part of a larger collective life, be integrated with it thorough and through. My parents’ life was. They were adjusted to themselves and to society. But the security of our world stops at our doorstep. “I am wounded in my fundamental societal impulses,” cries a man of genius, of my generation, in a burst of agony. What D.H. Lawrence felt, I feel, continually, overwhelmingly. It is not enough to say that he was an ill man we are both neurotics. Or rather, this neuroticism, if it be such, is epidemic. … I am giving publicity to my symptoms only because they are endemic, I believe, to the largest section of western intellectuals.”

This tension was a dilemma for Thompson as a self-identified liberal, because her sense of being wounded in her “fundamental societal impulses” made her sympathetic to an uncomfortable degree with the more radical politics of the era.

“… I could not accept the communist doctrine, still less could I accept the Nazi … Yet I share the discontent with existing society which made both movements possible. I cannot read half the newspapers or see the average Hollywood film without feeling ever so little like a Nazi, or observe the irresponsible antics of some of the rich, without feeling like a communist.”

Of the Communists she remarked,

I whom individualism and skepticism had set adrift in a world where everything was challenged and nothing believed, was drawn to these taut young people almost enviously.

And it was not just a psychological or emotional attraction. There was also a hard political lesson. Thompson had witnessed the fall of the Weimar Republic close up, but what really moved her was the destruction of Austrian social democracy in 1934.

When, later, the guns were turned against Vienna Social Democrats, and destroyed the only society I have seen since the war which seemed to promise evolution toward a more decent, humane, and worthy existence in which the past was integrated with the future, real fear overcame me, and now never leaves me. In one place only I had seen a New Deal singularly intelligent, remarkably tolerant, and amazingly successful. It was destroyed precisely because it was insufficiently ruthless, insufficiently brutal. “Victory” (I saw) requires force to sustain victory. I had wanted victory, and peace.

Something else was required.

Ultimately, it is tempting to say that Thompson’s extraordinarily prominent role in America’s war effort in World War II, would bring her the closure that she craved in her 1937 essay.

The war would catapult other individualist and skeptical intellectuals too into a convulsive embrace of history.

— from Adam Tooze, ‘Being There — Last Call At The Hotel Imperial’

Chartbook #110, 10 April 2022

‘Believe me, nice people don’t go Nazi. Their race, color, creed, or social condition is not the criterion. It is something in them.

‘Those who haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t—whether it is breeding, or happiness, or wisdom, or a code, however old-fashioned or however modern, go Nazi.’

— Dorothy Thompson

Who Goes Nazi?

Dorothy Thompson

It is an interesting and somewhat macabre parlor game to play at a large gathering of one’s acquaintances: to speculate who in a showdown would go Nazi. By now, I think I know. I have gone through the experience many times—in Germany, in Austria, and in France. I have come to know the types: the born Nazis, the Nazis whom democracy itself has created, the certain-to-be fellow-travelers. And I also know those who never, under any conceivable circumstances, would become Nazis.

It is preposterous to think that they are divided by any racial characteristics. Germans may be more susceptible to Nazism than most people, but I doubt it. Jews are barred out, but it is an arbitrary ruling. I know lots of Jews who are born Nazis and many others who would heil Hitler tomorrow morning if given a chance. There are Jews who have repudiated their own ancestors in order to become “Honorary Aryans and Nazis”; there are full-blooded Jews who have enthusiastically entered Hitler’s secret service. Nazism has nothing to do with race and nationality. It appeals to a certain type of mind.

It is also, to an immense extent, the disease of a generation—the generation which was either young or unborn at the end of the last war. This is as true of Englishmen, Frenchmen, and Americans as of Germans. It is the disease of the so-called “lost generation.”

Sometimes I think there are direct biological factors at work—a type of education, feeding, and physical training which has produced a new kind of human being with an imbalance in his nature. He has been fed vitamins and filled with energies that are beyond the capacity of his intellect to discipline. He has been treated to forms of education which have released him from inhibitions. His body is vigorous. His mind is childish. His soul has been almost completely neglected.

At any rate, let us look round the room.

The gentleman standing beside the fireplace with an almost untouched glass of whiskey beside him on the mantelpiece is Mr. A, a descendant of one of the great American families. There has never been an American Blue Book without several persons of his surname in it. He is poor and earns his living as an editor. He has had a classical education, has a sound and cultivated taste in literature, painting, and music; has not a touch of snobbery in him; is full of humor, courtesy, and wit. He was a lieutenant in the World War, is a Republican in politics, but voted twice for Roosevelt, last time for Willkie. He is modest, not particularly brilliant, a staunch friend, and a man who greatly enjoys the company of pretty and witty women. His wife, whom he adored, is dead, and he will never remarry.

He has never attracted any attention because of outstanding bravery. But I will put my hand in the fire that nothing on earth could ever make him a Nazi. He would greatly dislike fighting them, but they could never convert him. . . . Why not?

Beside him stands Mr. B, a man of his own class, graduate of the same preparatory school and university, rich, a sportsman, owner of a famous racing stable, vice-president of a bank, married to a well-known society belle. He is a good fellow and extremely popular. But if America were going Nazi he would certainly join up, and early. Why? . . . Why the one and not the other?

Mr. A has a life that is established according to a certain form of personal behavior. Although he has no money, his unostentatious distinction and education have always assured him a position. He has never been engaged in sharp competition. He is a free man. I doubt whether ever in his life he has done anything he did not want to do or anything that was against his code. Nazism wouldn’t fit in with his standards and he has never become accustomed to making concessions.

Mr. B has risen beyond his real abilities by virtue of health, good looks, and being a good mixer. He married for money and he has done lots of other things for money. His code is not his own; it is that of his class—no worse, no better, He fits easily into whatever pattern is successful. That is his sole measure of value—success. Nazism as a minority movement would not attract him. As a movement likely to attain power, it would.

The saturnine man over there talking with a lovely French emigree is already a Nazi. Mr. C is a brilliant and embittered intellectual. He was a poor white-trash Southern boy, a scholarship student at two universities where he took all the scholastic honors but was never invited to join a fraternity. His brilliant gifts won for him successively government positions, partnership in a prominent law firm, and eventually a highly paid job as a Wall Street adviser. He has always moved among important people and always been socially on the periphery. His colleagues have admired his brains and exploited them, but they have seldom invited him—or his wife—to dinner.

He is a snob, loathing his own snobbery. He despises the men about him—he despises, for instance, Mr. B—because he knows that what he has had to achieve by relentless work men like B have won by knowing the right people. But his contempt is inextricably mingled with envy. Even more than he hates the class into which he has insecurely risen, does he hate the people from whom he came. He hates his mother and his father for being his parents. He loathes everything that reminds him of his origins and his humiliations. He is bitterly anti-Semitic because the social insecurity of the Jews reminds him of his own psychological insecurity.

Pity he has utterly erased from his nature, and joy he has never known. He has an ambition, bitter and burning. It is to rise to such an eminence that no one can ever again humiliate him. Not to rule but to be the secret ruler, pulling the strings of puppets created by his brains. Already some of them are talking his language—though they have never met him.

There he sits: he talks awkwardly rather than glibly; he is courteous. He commands a distant and cold respect. But he is a very dangerous man. Were he primitive and brutal he would be a criminal—a murderer. But he is subtle and cruel. He would rise high in a Nazi regime. It would need men just like him—intellectual and ruthless. But Mr. C is not a born Nazi. He is the product of a democracy hypocritically preaching social equality and practicing a carelessly brutal snobbery. He is a sensitive, gifted man who has been humiliated into nihilism. He would laugh to see heads roll.

I think young D over there is the only born Nazi in the room. Young D is the spoiled only son of a doting mother. He has never been crossed in his life. He spends his time at the game of seeing what he can get away with. He is constantly arrested for speeding and his mother pays the fines. He has been ruthless toward two wives and his mother pays the alimony. His life is spent in sensation-seeking and theatricality. He is utterly inconsiderate of everybody. He is very good-looking, in a vacuous, cavalier way, and inordinately vain. He would certainly fancy himself in a uniform that gave him a chance to swagger and lord it over others.

Mrs. E would go Nazi as sure as you are born. That statement surprises you? Mrs. E seems so sweet, so clinging, so cowed. She is. She is a masochist. She is married to a man who never ceases to humiliate her, to lord it over her, to treat her with less consideration than he does his dogs. He is a prominent scientist, and Mrs. E, who married him very young, has persuaded herself that he is a genius, and that there is something of superior womanliness in her utter lack of pride, in her doglike devotion. She speaks disapprovingly of other “masculine” or insufficiently devoted wives. Her husband, however, is bored to death with her. He neglects her completely and she is looking for someone else before whom to pour her ecstatic self-abasement. She will titillate with pleased excitement to the first popular hero who proclaims the basic subordination of women.

On the other hand, Mrs. F would never go Nazi. She is the most popular woman in the room, handsome, gay, witty, and full of the warmest emotion. She was a popular actress ten years ago; married very happily; promptly had four children in a row; has a charming house, is not rich but has no money cares, has never cut herself off from her own happy-go-lucky profession, and is full of sound health and sound common sense. All men try to make love to her; she laughs at them all, and her husband is amused. She has stood on her own feet since she was a child, she has enormously helped her husband’s career (he is a lawyer), she would ornament any drawing-room in any capital, and she is as American as ice cream and cake.

II

How about the butler who is passing the drinks? I look at James with amused eyes. James is safe. James has been butler to the ‘ighest aristocracy, considers all Nazis parvenus and communists, and has a very good sense for “people of quality.” He serves the quiet editor with that friendly air of equality which good servants always show toward those they consider good enough to serve, and he serves the horsy gent stiffly and coldly.

Bill, the grandson of the chauffeur, is helping serve to-night. He is a product of a Bronx public school and high school, and works at night like this to help himself through City College, where he is studying engineering. He is a “proletarian,” though you’d never guess it if you saw him without that white coat. He plays a crack game of tennis—has been a tennis tutor in summer resorts—swims superbly, gets straight A’s in his classes, and thinks America is okay and don’t let anybody say it isn’t. He had a brief period of Youth Congress communism, but it was like the measles. He was not taken in the draft because his eyes are not good enough, but he wants to design airplanes, “like Sikorsky.” He thinks Lindbergh is “just another pilot with a build-up and a rich wife” and that he is “always talking down America, like how we couldn’t lick Hitler if we wanted to.” At this point Bill snorts.

Mr. G is a very intellectual young man who was an infant prodigy. He has been concerned with general ideas since the age of ten and has one of those minds that can scintillatingly rationalize everything. I have known him for ten years and in that time have heard him enthusiastically explain Marx, social credit, technocracy, Keynesian economics, Chestertonian distributism, and everything else one can imagine. Mr. G will never be a Nazi, because he will never be anything. His brain operates quite apart from the rest of his apparatus. He will certainly be able, however, fully to explain and apologize for Nazism if it ever comes along. But Mr. G is always a “deviationist.” When he played with communism he was a Trotskyist; when he talked of Keynes it was to suggest improvement; Chesterton’s economic ideas were all right but he was too bound to Catholic philosophy. So we may be sure that Mr. G would be a Nazi with purse-lipped qualifications. He would certainly be purged.

H is an historian and biographer. He is American of Dutch ancestry born and reared in the Middle West. He has been in love with America all his life. He can recite whole chapters of Thoreau and volumes of American poetry, from Emerson to Steve Benet. He knows Jefferson’s letters, Hamilton’s papers, Lincoln’s speeches. He is a collector of early American furniture, lives in New England, runs a farm for a hobby and doesn’t lose much money on it, and loathes parties like this one. He has a ribald and manly sense of humor, is unconventional and lost a college professorship because of a love affair. Afterward he married the lady and has lived happily ever afterward as the wages of sin.

H has never doubted his own authentic Americanism for one instant. This is his country, and he knows it from Acadia to Zenith. His ancestors fought in the Revolutionary War and in all the wars since. He is certainly an intellectual, but an intellectual smelling slightly of cow barns and damp tweeds. He is the most good-natured and genial man alive, but if anyone ever tries to make this country over into an imitation of Hitler’s, Mussolini’s, or Petain’s systems H will grab a gun and fight. Though H’s liberalism will not permit him to say it, it is his secret conviction that nobody whose ancestors have not been in this country since before the Civil War really understands America or would really fight for it against Nazism or any other foreign ism in a showdown.

But H is wrong. There is one other person in the room who would fight alongside H and he is not even an American citizen. He is a young German emigre, whom I brought along to the party. The people in the room look at him rather askance because he is so Germanic, so very blond-haired, so very blue-eyed, so tanned that somehow you expect him to be wearing shorts. He looks like the model of a Nazi. His English is flawed—he learned it only five years ago. He comes from an old East Prussian family; he was a member of the post-war Youth Movement and afterward of the Republican “Reichsbanner.” All his German friends went Nazi—without exception. He hiked to Switzerland penniless, there pursued his studies in New Testament Greek, sat under the great Protestant theologian, Karl Barth, came to America through the assistance of an American friend whom he had met in a university, got a job teaching the classics in a fashionable private school; quit, and is working now in an airplane factory—working on the night shift to make planes to send to Britain to defeat Germany. He has devoured volumes of American history, knows Whitman by heart, wonders why so few Americans have ever really read the Federalist papers, believes in the United States of Europe, the Union of the English-speaking world, and the coming democratic revolution all over the earth. He believes that America is the country of Creative Evolution once it shakes off its middle-class complacency, its bureaucratized industry, its tentacle-like and spreading government, and sets itself innerly free.

The people in the room think he is not an American, but he is more American than almost any of them. He has discovered America and his spirit is the spirit of the pioneers. He is furious with America because it does not realize its strength and beauty and power. He talks about the workmen in the factory where he is employed. . . . He took the job “in order to understand the real America.” He thinks the men are wonderful. “Why don’t you American intellectuals ever get to them; talk to them?”

I grin bitterly to myself, thinking that if we ever got into war with the Nazis he would probably be interned, while Mr. B and Mr. G and Mrs. E would be spreading defeatism at all such parties as this one. “Of course I don’t like Hitler but . . .”

Mr. J over there is a Jew. Mr. J is a very important man. He is immensely rich—he has made a fortune through a dozen directorates in various companies, through a fabulous marriage, through a speculative flair, and through a native gift for money and a native love of power. He is intelligent and arrogant. He seldom associates with Jews. He deplores any mention of the “Jewish question.” He believes that Hitler “should not be judged from the standpoint of anti-Semitism.” He thinks that “the Jews should be reserved on all political questions.” He considers Roosevelt “an enemy of business.” He thinks “It was a serious blow to the Jews that Frankfurter should have been appointed to the Supreme Court.”

The saturnine Mr. C—the real Nazi in the room—engages him in a flatteringly attentive conversation. Mr. J agrees with Mr. C wholly. Mr. J is definitely attracted by Mr. C. He goes out of his way to ask his name—they have never met before. “A very intelligent man.”

Mr. K contemplates the scene with a sad humor in his expressive eyes. Mr. K is also a Jew. Mr. K is a Jew from the South. He speaks with a Southern drawl. He tells inimitable stories. Ten years ago he owned a very successful business that he had built up from scratch. He sold it for a handsome price, settled his indigent relatives in business, and now enjoys an income for himself of about fifty dollars a week. At forty he began to write articles about odd and out-of-the-way places in American life. A bachelor, and a sad man who makes everybody laugh, he travels continually, knows America from a thousand different facets, and loves it in a quiet, deep, unostentatious way. He is a great friend of H, the biographer. Like H, his ancestors have been in this country since long before the Civil War. He is attracted to the young German. By and by they are together in the drawing-room. The impeccable gentleman of New England, the country-man—intellectual of the Middle West, the happy woman whom the gods love, the young German, the quiet, poised Jew from the South. And over on the other side are the others.

Mr. L has just come in. Mr. L is a lion these days. My hostess was all of a dither when she told me on the telephone, “ . . . and L is coming. You know it’s dreadfully hard to get him.” L is a very powerful labor leader. “My dear, he is a man of the people, but really fascinating.“ L is a man of the people and just exactly as fascinating as my horsy, bank vice-president, on-the-make acquaintance over there, and for the same reasons and in the same way. L makes speeches about the “third of the nation,” and L has made a darned good thing for himself out of championing the oppressed. He has the best car of anyone in this room; salary means nothing to him because he lives on an expense account. He agrees with the very largest and most powerful industrialists in the country that it is the business of the strong to boss the weak, and he has made collective bargaining into a legal compulsion to appoint him or his henchmen as “labor’s” agents, with the power to tax pay envelopes and do what they please with the money. L is the strongest natural-born Nazi in this room. Mr. B regards him with contempt tempered by hatred. Mr. B will use him. L is already parroting B’s speeches. He has the brains of Neanderthal man, but he has an infallible instinct for power. In private conversation he denounces the Jews as “parasites.” No one has ever asked him what are the creative functions of a highly paid agent, who takes a percentage off the labor of millions of men, and distributes it where and as it may add to his own political power.

III

It’s fun—a macabre sort of fun—this parlor game of “Who Goes Nazi?” And it simplifies things—asking the question in regard to specific personalities.

Kind, good, happy, gentlemanly, secure people never go Nazi. They may be the gentle philosopher whose name is in the Blue Book, or Bill from City College to whom democracy gave a chance to design airplanes—you’ll never make Nazis out of them. But the frustrated and humiliated intellectual, the rich and scared speculator, the spoiled son, the labor tyrant, the fellow who has achieved success by smelling out the wind of success—they would all go Nazi in a crisis.

Believe me, nice people don’t go Nazi. Their race, color, creed, or social condition is not the criterion. It is something in them.

Those who haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t—whether it is breeding, or happiness, or wisdom, or a code, however old-fashioned or however modern, go Nazi. It’s an amusing game. Try it at the next big party you go to.

***

Source:

- Dorothy Thompson, ‘Who Goes Nazi?’, Harper’s Magazine, August 1941

***

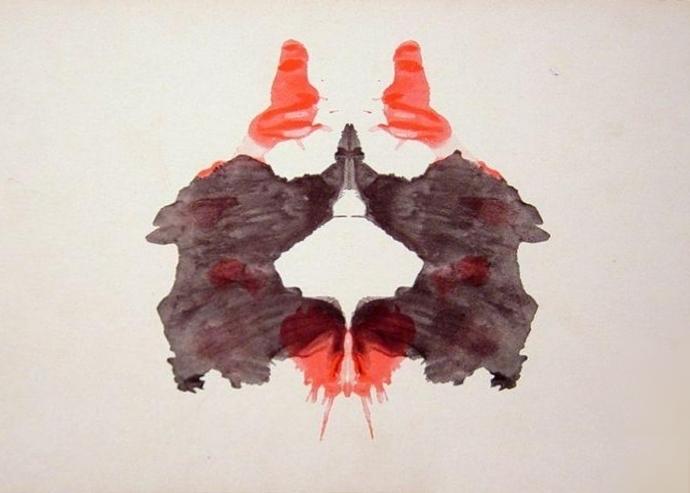

A Rorschach Test for Nazis

Damion Searls

An international military tribunal was created. “Crimes against humanity” were prosecuted for the first time, at the Nuremberg trials, beginning in 1945. Twenty-four prominent Nazis were chosen as the first group of defendants. But the moral quandaries remained. The defendants claimed that they had been following their own country’s laws, which in this case meant whatever Hitler wanted. Could people legally be held to account on the basis of a higher law of common humanity? How deep does cultural relativity go? And if these Nazis really were deranged psychopaths, then weren’t they unfit to stand trial, or even not guilty by reason of insanity?

The prisoners were held in solitary, on the ground floor of a three-story prison block with cells on both sides of a wide corridor. Each cell was nine by thirteen feet, with a wooden door several inches thick, a high barred window onto a courtyard, a steel cot, and a toilet, with no seat or cover, from which the prisoner’s feet remained visible to the guards. Personal belongings were kept on the floor. A fifteen-inch panel in the middle of the cell door was open at all times, forming a shelf in the cell on which meals were placed and a peephole for guards to look through, one guard per prisoner at all times. The light was always on, dimmer at night but still bright enough to read by, and heads and hands had to be kept visible while the prisoner was in bed, asleep or awake. Aside from harsh corrections when any rules were broken, the guards never spoke to the prisoners, nor did the wardens who brought them their food. They had fifteen minutes a day to walk outside, separate from the other prisoners, and showers once a week, under supervision. Up to four times a week, the prisoner was stripped and the room searched so thoroughly it took four hours to straighten up afterward.

They also had medical care, to keep them healthy for the trial. A staff of doctors weaned Hermann Göring off his morphine addiction, restored some of the use of Hans Frank’s hand after he had slashed his wrist in a suicide attempt, helped reduce Alfred Jodl’s back pain and Joachim von Ribbentrop’s neuralgia. There were dentists, chaplains—one Catholic, one Protestant—and a prison psychiatrist. This was none other than Douglas Kelley, coauthor of Bruno Klopfer’s 1942 manual, The Rorschach Technique.

Kelley had been one of the first members of the Rorschach Institute to volunteer after Pearl Harbor, and by 1944 he was chief of psychiatry for the European Theater of Operations. In 1945 he was in Nuremberg, assigned to help determine whether the defendants were competent to stand trial. He saw them for five months, making the rounds every day and talking to them at length, often sitting on the edge of a prisoner’s cot for three or four hours at a time. The Nazis, alone and bored, were eager to talk. Kelley said he had never had a group of patients so easy to interview. “In addition to careful medical and psychiatric examinations, I subjected the men to a series of psychological tests,” Kelley wrote. “The most important technique employed was the Rorschach Test, a well-known and highly useful method of personality study.” …

As early as 1946, even before the Nuremberg verdicts were handed down, Kelley published a paper stating that the defendants were “essentially sane,” though in some cases abnormal. He didn’t discuss the Rorschachs specifically, but he argued “not only that such personalities are not unique or insane, but also that they could be duplicated in any country of the world today.”

Kelley insisted on going against what the postwar public strongly believed, and even more strongly wanted to believe. The Nazis were, he wrote, “not spectacular types, not personalities such as appear only once in a century,” but simply “strong, dominant, aggressive, egocentric personalities” who had been given “the opportunity to seize power.” Men like Göring “are not rare. They can be found anywhere in the country—behind big desks deciding big affairs as businessmen, politicians, and racketeers.”

So much for American leaders. As for followers: “Shocking as it may seem to some of us, we as a people greatly resemble the Germans of two decades ago,” before Hitler’s rise to power. Both share a similar ideological background and rely on emotions rather than the intellect. “Cheap and dangerous” American politicians, Kelley wrote, were using race-baiting and white supremacy for political gain “just one year after the end of the war”—an allusion to Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi and Eugene Talmadge of Georgia; he also referred to “the power politics of Huey Long, who enforced his opinions by police control.” These were “the same racial prejudices that the Nazis preached,” the very “same words that rang through the corridors of Nuremberg Jail.” In short, there was “little in America today which could prevent the establishment of a Nazilike state.”

— Damion Searls, ‘The Nazi Mind’, The Paris Review, 22 February 2017

adapted from The Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and the Power of Seeing, Crown, 2017

***

Just About Anyone Could Go Nazi

One conclusion that can be firmly drawn from these analysis is related to the myth that the Nazis were highly disturbed and clinically deranged individuals. The current analysis clearly suggests that a majority of the Nazis were not deranged in the clinical sense and that the above described common personality characteristics, while undesirable to many, are not pathological in and of themselves and are actually frequently found in the U.S. population. Thus, as a group, the Nazis were not the hostile sadists many made them out to be. Yet, they were not a collection of random humans either. While the differences among the Nazis studied here far outweigh any similarities, and a Nazi personality cannot be simply defined in strict terms, the above personality traits may nevertheless serve as predisposing characteristics. In this sense the presence of them may make individuals more vulnerable to the influences of a Nazi movement, or for that matter, any political movement. These personality traits are, however, not considered diagnosable. We must therefore conclude that under certain social conditions, just about anyone could have joined the Nazi movement, but that there were individuals who were more likely to join.

— from E.A. Zillmer, M. Harrower, B.A. Ritzler & R.P. Archer, The quest for the Nazi personality: A psychological investigation of Nazi war criminals, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995, p.181

No people ever recognize their dictator in advance. He never stands for election on the platform of dictatorship. He always represents himself as the instrument [of] the Incorporated National Will. … When our dictator turns up you can depend on it that he will be one of the boys, and he will stand for everything traditionally American. And nobody will ever say ‘Heil’ to him, nor will they call him ‘Führer’ or ‘Duce.’ But they will greet him with one great big, universal, democratic, sheeplike bleat of ‘O.K., Chief! Fix it like you wanna, Chief! Oh Kaaaay!’

— Dorothy Thompson, 1937

***

Gurl, You’re a Karen

Randy Rainbow

A parody written and performed by Randy Rainbow.

Based on ‘Dentist!’ by Alan Menken & Howard Ashman

from Little Shop of Horrors

‘You lie and call scientists Nazis

While actual Nazis you bless.’

— from ‘Gurl, You’re a Karen’, 15 March 2022

Watch ‘Gurl, You’re a Karen’ on YouTube

***

When Dorothy Thompson Was Cancelled

‘I wondered about my father’s faith in the innate goodness in every human being; I wondered whether any amount of law and policing could remove evils as long as there were evil people.’

— from Dorothy Thompson, unpublished memoir, quoted in

Karine Walther, ‘Dorothy Thompson and American Zionism’

‘Dorothy became a Zionist very early in her career. It was accidental almost. She was traveling to Europe on a boat in 1920 and there was a collection of American Zionists, including Chaim Weizmann, who were going to London for a conference and she was just starting out as a reporter and she fell in with them and got some very interesting early stories that persuaded her on first acquaintance of the nobility of the Zionist cause. And then later on during the Hitler years when the plight of the Jews in Europe was much under consideration, by her at least. She continued to think that a homeland for the Jews was the proper and sane thing to agitate for until it happened basically and she began to study the region of the Palestine and the Middle East in-depth and on-site. And she concluded very rapidly that you could not buy the piece of your conscience by uprooting the other people from their own land, which is what she saw happen in Israel, and she quickly determined that in her view the Zionist movement in Israel was as violent, it was authoritarian, it was fascist and it was terrorist, actually, in order to achieve its goals. So she opposed it very early before Israel actually came into being, she was already beginning to warn that it was a recipe for perpetual warfare, as she called it.

‘The Zionist leaders regarded Dorothy Thompson as a great friend and ally through most of the 30s, certainly, when she was openly on their side, and during the war too. They regarded her as a white light, as a strong voice for justice in their cause. That began to change only when she became aware of what the peace in World War II was going to look like. She believed that the Nazis should be dealt with like any other defeated enemy in any war that we’ve had and not punished in particular for going to war, which is what the Allies were doing. They were calling for unconditional surrender and to remove all authority and all rights from whatever emerges as the German government. And she saw that the persecutions of people in Europe was not confined to the Nazi party, that in the wake of World War II there were millions and millions of dead in atrocities and murders of mass slaughters, in the revenge killings. She called for a just and humane peace, and she thought that Israel was not the solution to the bad conscience of the West, she put it. She saw that the West had done very little, the Allies had done very little to assist the Jews at a time when it might mattered, or it might’ve helped, and they could not buy the peace of their conscience by carving out a piece of the Middle East for the Jews, so the Zionist leaders quickly turned against her in the closing days of World War II. And during the two or three years before the founding of the state of Israel she was calling them terrorists openly—Zionists in Jerusalem—and they turned against her vituperatively and made it their business as a political organization, a political movement, to undermine their authority and attack her integrity wherever they could.’

— Peter Kurth, interview #1, The Silencing of Dorothy Thompson, 13 July 2013

***

‘[O]ne of the truly great women of our century, spent her final years in an atmosphere of scorn, derision, and personal vilification.’

— Meyer Weisgal . . . so far: An Autobiography, New York, 1971, p.193

***

“We acted like Germans, automatically, we didn’t think.”

Karine Walther

In 1951, [Dorothy] Thompson founded and subsequently presided over the American Friends of the Middle East (AFME), an organization which dedicated its efforts to altering U.S. policy on Israel and repairing the country’s relationship with the Middle East. The AFME’s founding members were united in their belief that U.S. support for partition and Israeli statehood were the most damaging decisions made by President Truman in the country’s relationship with the Middle East. Some AFME members believed Truman had betrayed American values in exchange for domestic political benefits. One of the organization’s founding members, William Eddy, recalled in a book published by the AFME that Truman had responded to his and other diplomats’ concerns about U.S. support for Israel by explaining: “I’m sorry, gentlemen, but I have to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism. I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.” Truman later admitted that the influence of American Zionist organizations during this time had been intense: “I do not think I ever had as much pressure and propaganda aimed at the White house as I had in this instance.”

Besides Eddy, the son of Protestant missionaries in the Middle East who worked as a consultant for Aramco, and had previously served as the Minister to Saudi Arabia, the AFME’s membership included a range of other former diplomats, prominent academics, and Protestant liberal activists. These included the former UN delegate and dean of Barnard College, Virginia Gildersleeve, Cornelius H. Van Engert, a former diplomat who had served in several Middle Eastern countries, Harvard philosophy professor William Ernest Hocking, Presbyterian minister and theology professor Henry Sloan Coffman, the former president of the American University of Beirut, Bayard Dodge, Lebanese-American Harvard professor Philip Hitti, and the Protestant liberal intellectual, Harry Emerson Fosdick. Many of these members had developed deep ties to Arabs in the Middle East due to their work in the region, relationships that led them to reject the demeaning depictions of Arabs often used to justify Zionism during this time. Some had also served in organizations dedicated to aiding Palestinian refugees and opposing the 1947 UN partition of Palestine. Two of these, the Committee for Justice and Peace in the Holy Land and the Holyland Emergency Liaison Program (HELP), were subsequently absorbed by the AFME.

The AFME also secretly received substantial financial support from the CIA, undoubtedly facilitated by its head, Allen Dulles, and some of its undercover members, including Kermit Roosevelt, Jr. Dulles had previously briefly served on HELP’s board alongside Roosevelt, Jr. and shared a network of contacts with many AFME members due to his previous work for the Near East College Association. Although Roosevelt, Jr. supported the AFME and remained privately involved, his name did not appear on the official membership list. According to one scholar, he may have served as the liaison between the CIA and the AFME. The CIA’s financial support for the AFME reflected broader disagreements within the U.S government over its support for Israel, views that also extended to many members of the State Department.

While the CIA donated funds to the AFME, its exact influence over the organization is unknown because these documents remain classified. Nonetheless, in response to one AFME member’s insinuations that the Dearborn Foundation (the organization through which the CIA funneled its money) was influencing the AFME to reduce its emphasis on Zionism, the organization circulated several internal documents refuting the attacks, including one where the vice president noted that the foundation “has never at any time attempted to interfere with the policies established by our board of directors.” Writing to another member, Thompson put it more concisely: “The man seems to me to be a pure nut.” Given the private nature of this correspondence between members who would have been “in the know” about CIA funding, there was little reason for them to make such claims. The CIA’s financial support clearly facilitated the AFME’s ability to perpetuate their views, but it was not responsible for initiating them.

To counter American Zionist organizations’ efforts to shape American public opinion, the AFME ran its own propaganda campaign, organizing conferences and publishing books and pamphlets about Palestine and the broader Middle East. An early AFME report explained that its mission was: “to interpret the real America with its ideals of freedom, justice and peace for all the people of the world. We have frankly admitted that in some of our relationships with the Middle East we have fallen short of our own high American ideals.” The report did not explicitly state where these failures lay, but there was little doubt about what it was referring to. AFME members denounced Israeli policies more explicitly in other venues. Thompson critiqued the illiberal nature of Israel in a 1951 speech for the ACJ, arguing that “despite all the claims of the Zionists” Palestinian Arabs in Israel “live as second-rate citizens, with serious restrictions on their rights.” The AFME also adapted post-war rhetoric about the United States’ Judeo-Christian identity by highlighting the shared religious and historical ties between Christianity and Islam, which they framed as part of the broader war against “Soviet Atheism.”

Other AFME members argued that support for Israel undermined the United States’ alleged opposition to imperialism. Eddy highlighted this contradiction in a 1953 speech at the American Naval Academy where he critiqued the United States’ pro-imperial foreign policy in support of Israel and ongoing French and British colonialism in the region. AFME members were not the first to highlight these contradictions. Third World nationalists, including the delegate from the newly independent Philippines, Carlos Romulo, raised these critiques during debates that preceding the UN partition vote in 1947. Romulo drew on anti-imperialist and anti-racist arguments to maintain that partition betrayed the “primordial rights of a people to determine their political future and to preserve the territorial integrity of their native land,” and extended unacceptable historical practices of “racial exclusiveness” to the Middle East. Succumbing to U.S. pressure, the Philippines, Haiti, Liberia, and other countries subsequently changed their votes to favor partition. The United States’ ability to exert this pressure, ironically, drew on its history of exerting its imperial power over these very countries.

In the same speech, Eddy reaffirmed the AFME’s arguments that U.S. support for Israel undermined its commitments to civic nationalism and pluralism. He highlighted the betrayal felt by former students educated in American institutions in the Middle East who had been taught to believe in “American liberties which bridge religion, national origin and language to weld a United States.” While these graduates had succeeded in “bringing together at the same table and in the same club Muslim and Christian, Druze and Maronite,” they were now “struck down by America which forced the establishment in Palestine of a state which, by its own constitution, first-class citizenship is reserved to the adherents of only one religion—as Hitler admitted priority to only one race” leading these Arabs to feel that their “best friend [had] inexplicably struck” them in the face. …

While the AFME opposed U.S. support for Israel by arguing that it ran counter to American efforts to spread democracy abroad, one of the organization’s supporters engaged in actions that belied these noble public claims. In 1953, Roosevelt, Jr., participated in Operation AJAX, organized by the CIA and the British to oust the democratically-elected Iranian prime minister, Mohamed Mosaddeq, after he helped nationalize his country’s oil resources. In that case as well, U.S. officials privately resorted to the spectre of communism to justify their actions. These inconsistencies were not limited to Roosevelt, Jr. Thompson and other AFME members’ lofty commitments to egalitarian democracy abroad were often accompanied by their failure to fully acknowledge its limitations at home. Although Thompson actively repudiated antisemitism, she failed to fully recognize its ongoing reality. Indeed, while antisemitism in the United States never reached the levels found in Europe, Jews continued to face hostility and exclusion in American society, a situation made painfully clear in 1939 when 83% of Americans polled by a Fortune survey expressed their opposition to raising quotas to accept more Jewish refugees.

Thompson’s definition of civic nationalism was grounded in an exceptionalist mythology that was simply unrecognizable for many American minorities. She expressed these views in her 1950 article for Commentary where she argued that: “There are no minorities in the United States. There are no national minorities, racial minorities, or religious minorities … American democracy is based on equality of right for every individual citizen and religious group, with neither inherent rights nor inherent prejudices for or against any national groups—which are simply not recognized.” Thompson’s claim reflected profound optimistic ignorance at best or disingenuousness at worst. She wrote her column at a time when African Americans continued to face legalized segregation and de facto disenfranchisement in the South and less than a decade after the U.S. government had interned over eighty-thousand Japanese-American citizens based solely on their ethnicity. Thompson’s attempt to explain away African Americans’ lack of political rights in the article by pointing to their “unique” historical circumstances, alongside her optimism that this situation would be alleviated by “gradual racial assimilation” only reinforced her failure to fully recognize the realities of American democracy.

More controversially, Thompson argued in the same article that Jewish-Americans’ support for Israel conflicted with U.S. principles first outlined by George Washington’s “Farewell Address” warning about foreign attachments, by inspiring a dual loyalty among American Jews that threatened U.S. national security. Thompson’s willingness to deploy such a loaded accusation demonstrated a stunning lack of sensitivity to the historical weaponization of such tropes against Jews, one that had previously also been deployed against Japanese Americans and Catholic Americans. Paradoxically, while Berger had expressed concerns about the resurgence of such accusations, he encouraged Thompson to express this argument. While both might have objected to the exclusionary nature of Israeli policies for valid moral reasons, the very premise of attacking Americans, many of whom were immigrants, for supporting another nation’s interests alongside those of the United States was steeped in a belief in blind national loyalty. This view also advanced a reductive definition of American citizenship that demanded defending U.S. interests above those of any other country, regardless of the validity or morality of those interests.

In the same issue of Commentary, immigration historian Oscar Handlin, himself the son of Russian Jewish exiles escaping persecution, offered a powerful rebuttal to Thompson’s exclusionary arguments about American identity. He critiqued the xenophobic World War I origins of Thompson’s views and instead celebrated American ethnic pluralism. Handlin, however, made his own questionable claims in his rebuttal, arguing that American Jews who emigrated to Israel were carrying “the ideals of American democracy to another part of the world.” Whether or not Handlin was aware of the extent of Israel’s own rejection of ethnic pluralism and its policies denying Palestinian citizens in Israel full political rights, his claim that American Jewish immigrants were bringing U.S. democracy to Israel surely did not have the racial exclusivity of its practices in mind.

The AFME’s critiques of Israel did not go unchallenged. As its founder and president, Thompson faced the brunt of this backlash. American Zionists publicly accused her and the AFME of antisemitism and of being bribed by Arab oil interests. Other attacks were more personal, claiming that Thompson’s views were driven by her husband, the Czech-born artist Maxim Kopf, whom they publicly and falsely labeled as a Nazi and Communist sympathizer. These attacks convinced more newspapers to drop her column. Given her ongoing popularity, other newspapers maintained their subscription but refused to print her columns when they critiqued Israel.

The professional repercussions of these attacks reached such a level that Thompson believed she had enough evidence to sue the newspapers publishing these accusations for libel. While she had neither the time nor the money to do so, she did successfully level this threat against Rabbi Baruch Korff, who published a letter in the New Hampshire Manchester Union Leader in 1953 accusing Thompson of being “a paid propagandist of the Arabs,” a “seasoned anti-Semite,” a “Goebels-minded [sic] publicity agent,” and a “mercenary ill-motivated agent for the heirs of Naziism.” This was not the first time Korff had weaponized accusations of antisemitism. In 1948, he authored the text of a full-page ad published on behalf the Political Action Committee for Palestine in the New York Post accusing Warren Austin, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, of antisemitism for issuing a statement on partition to the Security Council that he felt lacked enough commitment to the project.

Korff’s motivations to attack Thompson were also personal. Before settling in New Hampshire, he had worked with the Stern Gang and Irgun to organize terrorist activities against the British, which included a failed plot to drop a bomb, alongside Stern Gang pamphlets, on London. Thompson had covered Korff’s involvement in the bombing scheme in one of her columns in 1947, labeling him and his accomplices “American guerillas,” an accusation Korff cited in his response to Thompson’s threat to sue him for libel. She responded that in contrast to his accusations, her label had been factual. What Thompson did not know at that time was that Korff had continued to secretly support militant actions through his organization’s fundraising for the Irgun. While in this case, Thompson’s threats proved effective in forcing Korff to retract some of his accusations, she was unable to address the wider campaign attacking her views. Broader efforts to silence the AFME were far reaching, extending to the Israeli Office of Information, which contacted American Jewish organizations about combatting the AFME and infiltrating the organization to better monitor its activities.

Executives at the Bell Syndicate, which managed Thompson’s syndicated column, believed that American Zionist organizations were behind the letter campaigns demanding that newspapers drop her column, noting the similar language replicated across the letters and the fact that correspondence to local newspapers was sent by individuals from different states. Nonetheless, the financial and reputational damage these attacks were inflicting on the syndicate led them to pressure Thompson to resign from the AFME. As the syndicate’s president maintained, Thompson needed to make a choice between being “a journalist or a propagandist.” Thompson eventually capitulated to their demands, abandoning her affiliation with the AFME in 1957. Her experience reinforced her belief that beyond the limitations of Israel itself, its American supporters were threatening the liberal values which she held most dear, freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Even after leaving the AFME, Thompson continued to receive hate mail from readers. Some weaponized Cold War anti-communism against her. One letter writer attacked her critiques of Israel and warned that he would be reporting her to the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee because he detected “a touch of communism” in her columns. These views reflected the ongoing application of Cold War rhetoric to defend Israel. Indeed, in 1957, Senator Herbert H. Lehman (D-NY) publicly defended Israel by arguing that: “a combination of Arab totalitarianism and Communist terror is creating a situation of homelessness and horror for at least 100,000 Jewish refugees.” Of course, Lehman failed to note that by 1957, Israeli policies had made almost a million Palestinian refugees homeless and stateless. Reflecting rising support for Israel among Christian Zionists, another letter writer countered Thompson’s “assault of half-truths” by presenting his version of reality: “Here is the truth … The establishment of the state of Israel is in accordance with the will of God.” Truman’s decision to recognize Israel had not been for politics alone, the writer maintained, but so “that Scripture might be fulfilled.”

Although Thompson agreed to resign from the AFME, she did not fully give up on her activism. In a speech delivered a few months after her resignation, she recalled her visit to Dachau two decades earlier. This time, she compared the immoral behavior of Nazis to policies enacted by both Israel and the United States. She began her speech by condemning the atrocities committed by Israeli soldiers during the Kafr Qasim Massacre the previous year, resulting in the murder of 48 Israeli Palestinian citizens, including 23 children. Although the Israeli government banned local coverage of the story, word soon leaked to the international press, forcing the state to file charges against the soldiers. In her speech, delivered while the trial was still in process, Thompson noted the testimony of one soldier who admitted that shooting civilians, including infants, had not bothered him: “They are all our enemies.” His testimony was reflective of other officers’ views. Shalom Ofer, who ordered soldiers to shoot Palestinians and “mow them down,” expressed no regret for his actions during his testimony, nor did he appear to recognize the paradoxical nature of his explanation: “We acted like Germans, automatically, we didn’t think.” Thompson lamented that the massacre had failed to elicit a “serious or widely felt compunction in Israel or in the World Zionist Community.” Indeed, two years later, Ben-Gurion pardoned all of the soldiers who had been sentenced for their crimes. Thompson then turned her moral critique to Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan, noting that his order “was given by a good Baptist and a fond father, who was immediately afterward photographed with a wide grin.” She concluded that the lesson of Dachau remained that Dachau could occur anywhere.

After losing her husband in July of 1958 and facing ongoing attacks, Thompson essentially ended her journalistic career. She began devoting her time to writing her autobiography, fearful that the public attacks she had endured would damage her legacy, just as they had damaged her professional career and reputation. She acknowledged that her views had cost her dearly: “It has lost me thousands of previous admirers and scores of personal friends. It has closed platforms to me which once eagerly sought me as a speaker. It has mobilized against me one of the most powerfully organized and zealous groups in American public life . . . And it has often filled my heart with tears.” Weisgal confirmed Thompson’s experience in his memoirs: “one of the truly great women of our century, spent her final years in an atmosphere of scorn, derision, and personal vilification.”

Despite the repercussions Thompson faced for her views, she defended her moral and journalistic integrity: “I have written and said what I believe to be the limpid truth … The test of the truth, in this question as in all others, will be made by the developments of history.” In the end, her predictions about the developments of history proved remarkably accurate. In 1951, she had warned a friend that Arab-Israeli relations would never improve while the issue of Palestinian refugees remained unaddressed and while Israel’s borders remained unfixed. Reflecting undue optimism, however, in the same letter she qualified Arab fears “that Israel has boundless ambitions in the Middle East, and that any steps she may take to realize them by a step-by-step process will never be opposed by the United States” as a “neurosis.” On this point, their predictions proved more accurate.

Thompson passed away in 1961 with her memoirs unfinished, leaving others to write her story. As a result, her defense of Palestinian rights has often been erased from her legacy. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s online exhibit on Thompson includes her anti-Nazi activism and efforts to aid Jewish refugees, but end before her activist turn towards Palestinian rights. The same is true for the Britannica Encyclopedia’s online entry on Thompson. This erasure has contributed in reinforcing dominant narratives about Israel, while downplaying the serious moral and political concerns many Americans expressed about the project during this time.

The leveraging of American values by supporters and opponents of Zionism after World War II offers an important lens into wider political debates over nationalism and liberalism and reveals how Americans often interpreted Israel through their own political and historical lens, a pattern that has continued to inflame disagreements over this issue. Indeed, personal attacks against scholars and activists who have questioned the United States’ support for Israel or refused to adopt comforting narratives about its political project have continued into our present moment. Scholars and activists, including Jewish Americans, have faced blistering public denunciations of their critiques, including accusations of antisemitism. As Walter Hixson has noted, “there is a price to pay” for scholars in the United States who do so. American Zionists’ public and private attempts to silence Thompson and other critics demonstrate that these efforts emerged well before 1967, with great effect. Reinserting these views more fully into the history of Americans’ relationship with Zionism reminds us that the fraught debates over Israel in our current moment, including continuing efforts to silence its critics, have a much earlier genesis.

***

Source:

- Karine Walther, ‘Dorothy Thompson and American Zionism’, Diplomatic History, vol.46, no.2 (2022): 263-291, at pp.281-291. The heading of this section — “We acted like Germans, automatically, we didn’t think.” — is taken from the text and the footnotes of the original have been deleted