Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter VII

人一走 茶就涼

In the first Chaguan column in The Economist on 13 September 2018, David Rennie featured the teahouse culture of Chengdu in Sichuan. The chaguan 茶館 of the city had long been prey to the vicissitudes of modern China: they had suffered under the Nationalists before 1949, as well as under the Communists, after 1949. In particular, Rennie noted that in the Cultural Revolution ‘slow tea-sipping was called time-wasting, vain and bad. Maoist zealots closed teahouses.’ After Mao’s death in 1976, however, teahouses made a reappearance. They ‘are more than places to buy a drink’, Rennie continued:

They represent something precious: a space that is public yet not state-controlled, where citizens may speak, listen and be moved, find work, do deals or seek redress, or simply idle for a while. Today that spirit can be found online or in the gig economy, despite government controls. It is seen when citizens’ groups report injustices, displaying a complex mix of distrust and trust in officials, whose help they seek while doubting what it can achieve.

He had concluded that first column with the observation that:

Long ago, in a spirit of teasing respect, teahouse waiters were dubbed “tea doctors” [茶博士]. To be a tea doctor, patiently serving while patrons talk, seems a good ambition for a China columnist. Stoke the stove, then.

On 28 August 2024, David Rennie published his last Chaguan essay. In celebration of his achievement we also introduce readers to the Tea 茶 issue of China Heritage Quarterly (March 2012), the online journal launched in 2005 in which we first advocated New Sinology.

***

The expression ‘when the guest departs, the tea goes cold’ 人走茶凉 (originally 人一走 茶就涼) looks and sounds like one of those formulaic and often venerable set-expressions — clichés 成語, if you will — that are a feature of the Chinese language. In fact, it is the invention of Wang Zengqi (汪曾祺, d.1997), a fiction writer and essayist who co-wrote the libretto of Shajia Bang 沙家浜, one of the model revolutionary Peking operas sponsored by Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife.

Set during the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, the action of the opera revolves around a teashop in the countryside in the Yangtze Valley run by Elder Sister Ah-Qing 阿慶嫂, an underground Party member who secretly support the resistance. The line ‘when the guest departs, the tea goes cold’ 人一走 茶就涼 occurs in an aria sung by Ah-Qing when she is exchanging barbs with some local collaborators with the Japanese invaders. See A Battle of Wits 智鬥, the fourth act of the opera:

***

Today, ‘the tea turns cold when people move away’ is often used to describe how time and distance can undermine a relationship. In politics, it means ‘as soon as someone leaves power they lose influence’. In August 2015, People’s Daily published a pointed commentary warning retired Party leaders not to interfere with the new power holders. Invoking the authority Confucius in the form of a line from The Analects — ‘do not discuss the politics of an office that is not yours’ 不在其位,不謀其政 — the commentary acerbically noted that ‘some retired officials are unwilling to accept their post-retirement “cold tea”.’ In fact, ‘they do their utmost to keep their brew hot.’ In a not-so-subtle warning to yesterday’s men to keep their noses out of Xi Jinping’s business, the People’s Daily declared that ‘cold tea is very much the norm’ 人在茶才熱,人走茶自涼純屬正常.

In 220 Chaguan columns written over six years, David Rennie effectively offered an account of what we might come to think of as the ‘High Xi Jinping era’, one that stretches from the Chairman of Everything’s accession to unlimited and unparalleled power to the vainglorious slow-rolling decline of recent years. (In collaboration with his colleague Alice Su, from 2022 Rennie also made the exemplary podcast Drum Tower.)

In his final Chaguan column, Rennie noted that the teahouse would resume operation once his successor had secured a visa to take up residence in Beijing. (See also Exit interview: David Rennie ends 6 years covering Beijing for ‘The Economist’, NPR, 17 September 2024.)

***

This chapter is paired with ‘China, the Yin-Yang Nation’, Chapter Six in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. It is dedicated to the memory of Marco Ceresa, a distinguished Sinologist and a scholar of China’s tea culture.

My thanks to Lois Conner for permission to reproduce some of her work and Reader #1 for kindly going over the draft of this maundering chapter.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

3 September 2024

***

Further Reading

- Tea 茶, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 29 (March 2012)

- The China Critic 中國評論週報, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 30/31 (September 2012)

- Qin Shao 邵勤, Tempest over Teapots: The Vilification of Teahouse Culture in Early Republican China, The Journal of Asian Studies, vol.57, no.4 (November 1998): 1009-41

- Wang Di’s 2008 book, The Teahouse: Small Business, Everyday Culture, and Public Politics in Chengdu, 1900-1950, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008. For an excerpt in China Heritage Quarterly, see Sichuan Teahouses: Places for Politics

- Yuwen Wu, Tea? Reining in dissent the Chinese way, BBC, 15 January 2013

- James A. Benn, Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History, Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015

- 國家安全部,聽勸,別讓國家安全機關請你喝這“十杯茶”, CCTV,2024年1月30日

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

Seven Bowls of Tea

七碗詩

Lu Tong (盧仝, 790-835)

The first bowl moistens my lips and throat;

The second bowl breaks my loneliness;

The third bowl searches my barren entrails but to find

Therein some five thousand scrolls;

The fourth bowl raises a slight perspiration

And all life’s inequities pass out through my pores;

The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones;

The sixth bowl calls me to the immortals.

The seventh bowl could not be drunk,

only the breath of the cool wind raises in my sleeves.

Where is Penglai Island, Yuchuanzi wishes

to ride on this sweet breeze and go back.

一碗喉吻潤

二碗破孤悶

三碗搜枯腸

惟有文字五千卷

四碗發輕汗

平生不平事盡向毛孔散

五碗肌骨清

六碗通仙靈

七碗吃不得也

唯覺兩腋習習清風生

蓬萊山在何處玉川子

乘此清風欲歸去

— translated by Steven R. Jones

[Note: On the Chinese Ministry of State Security’s ‘ten cups of tea’, see 國家安全部,聽勸,別讓國家安全機關請你喝這“十杯茶”, CCTV,2024年1月30日。]

***

Chaguan—Teahouses

In the Editorial to Tea, an issue of China Heritage Quarterly, I noted that:

In the teahouse people would engage in idle gossip 閒談, chat 聊天, rant 侃山 and brag shamelessly 吹牛. It was, and in many places throughout China, an environment in which tall tales 大話 and arrant nonsense 廢話 can hold the day; it’s also where the chatter on the streets 道聽途說 is elaborated and circulates with the speed of a prairie fire. It is over tea too that people gather to play mah-jongg with clamorous concentration, although tea is just as much a boon companion that is suited to quieter moments of relaxed repose 閒適 and thoughtfulness 静思, as it is for conviviality and calm conversation.

***

As I note below, my first encounter with Chinese teahouses was in Chung Kuo, Cina, a documentary film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni released in 1972 and screened on Australian TV in mid 1974. By the end of the year, I was studying in Shanghai and in the new year I had tea at the Yu Yuan Garden teahouse featured in Antonioni’s film. At Fudan University, where I was studying, however, tea-drinking was generally a lugubrious affair. Our teachers and the school leadership invited us to ‘tea meetings’ 茶話會, droning affairs featuring tea brewed with what tasted like floor-sweepings which focussed on the confusing politics of the day. As modest bowls of peanuts were a feature of the gatherings, French classmates dubbed them ‘cacahuète briefings’ (for a latter-day ‘tea meeting’, see When Comrade Xi invited Monsieur Macron to tea).

After a few bleak years ‘beyond the wall’ in northeast China, I would have my first experience of ‘drinking tea’, or yumcha, in Hong Kong and Guangzhou. Then, back in Beijing in 1978 during the Xidan Democracy Wall movement, I was introduced to the raffish charms of the unofficial chaguan that sprung up in a furtive wave after a hiatus of over a decade.

The Beijing tea houses were colourful epicentres of political gossip and rumour-mongering. Blustering old-school story-tellers took to jerry-built stages to entertain the clientele — mostly shift workers and retirees in the neighbourhood — peppering episodes from classical novels like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin with cleverly disguised comments on contemporary politics. Around that time I was also introduced to Ying Ruocheng, an actor who would soon be acclaimed for his role in Teahouse 茶館, a 1950s play by Lao She revived as part of the post-Mao cultural rebirth. Although the play would be a hit in Beijing and went on to enjoy an international run, the gossipy, edgy and politically insouciant culture of real Beijing teahouses was doomed. By late 1979, the Communist Party was reasserting its deadening control over the capital’s teahouses in a mini cultural purge (the first of many more to come). Despite the fitful efforts of members of the newly emergent entrepreneurial class, entertainers, raconteurs, alleyway wags and thirsty audiences, the free-wheeling chaguan culture of that short-lived moment would never be the same. Meanwhile, Taipei, the other Chinese capital, soon saw the birth of the teahouse as salon; Wistaria Teahouse 紫藤廬, which opened in 1981, flourished as Beijing’s teahouses foundered. Soon it was the centre of the capital’s counterculture and, as the era of martial law drew to an end, of its underground politics.

In 1988, a decade after the brief reappearance of old-style teahouses in Beijing, the Lao She Teahouse 老舍茶館 opened near Tiananmen Square. A glitzy tourist trap that offered tea, food and clamorous performances. This kitsch reprisal of an imagined cultural icon was a sign of things to come.

***

As David Rennie notes in his own Chaguan, when money, taste and political leniency promised another revival in the early 2000s, there were new challenges: the consumer capitalism of Starbucks and the appeal of upscale Taiwanese tea establishments.

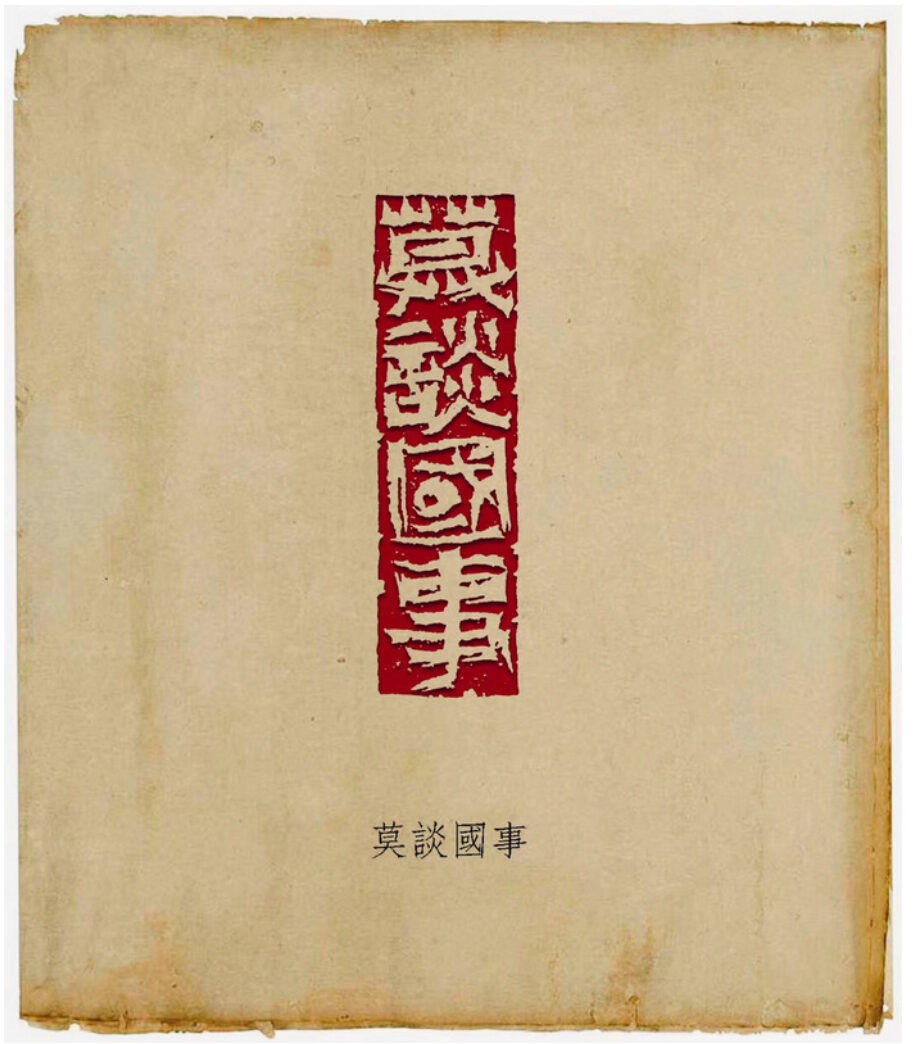

[Note: Although Ying Ruocheng was widely celebrated, he had a noxious reputation in the theatre world. Wu Zuguang, a celebrated playwright and the Master of Layabouts Lodge, who had been subjected to decades of persecution, was particularly scathing about Ying and his wife’s work for the security organs and I soon learned that the hospitable couple’s ‘marks’ included W. Allyn Rickett and Adele Austin Rickett, two Fulbright scholars from America becalmed in Beijing in 1950. Prisoners of Liberation: Four Years in a Chinese Communist Prison (1957), their account of those years, remains an unsettling record of their intelligence gathering, imprisonment and experience of thought reform. In an autobiography written in collaboration with Claire Conceison, Ying skirts around his ignominious role in the persecution of the Ricketts and others. (See Voices Carry: Behind Bars and Backstage during China’s Revolution and Reform, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, pp.xx–xxiii, 49-55, 78 and 200-202). The famous tag-line of Lao She’s play Teahouse — a production which brought Ying fame and fortune — is ‘don’t discuss politics!’ 莫談國事. To think that in real life Ying Ruocheng and his wife’s ‘side-hustle’ was all about enticing people to discuss politics … They might have also appreciated the gloomy ramifications of the expression ‘being invited to have a cup of tea’ 被請喝茶。]

***

The Yu Yuan Garden Pond-heart Teahouse 豫園湖心亭茶樓 in the old city of Shanghai is one of the most famous, and venerable in years, in China. It is also one of the few genteel traditional-style tea establishments that survived even during the Cultural Revolution. It features in Michelangelo Antonioni’s fascinating if somewhat notorious (although now generally forgotten) 1972 documentary film Chung Kuo, Cina.

***

Earlier in the Shanghai segment of Chung Kuo, Antonioni had visited the site of the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, founded in that city in July 1921 at a gathering of twelve men. They supposedly were seated around a table drinking tea. The Italian director shows the empty room now a display of what would be a momentous event. The camera pans over the surface of the highly polished conference table and notes the carefully arranged teacups and pot, all that remained to mark a spectral moment that altered the course of Chinese history.

[Note: For this scene in Chung Kuo, Cina, see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dz_VB4dkcRw at 9:10-9:35.]

***

Even in the impoverished days of the early 1970s, the teahouse next to the Yu Yuan Garden continued to served desultory customers. The teahouse is housed in a building that was re-constructed in 1784, in the dying years of the Qianlong reign era. Renamed the Yeshi Pavilion 也是軒 in 1855, during the Xianfeng reign era, tea was sold there and today it is one of the most famous tea establishments in the People’s Republic. Even in 1970s it was a popular spot. Although the various confections and delicacies for which it had once been renowned were reduced to naught, customers could meet friends there, visit with family members or simply read the paper while they sipped tea, chatted and looked out over the scenery.

In Chung Kuo, Cina, Antonioni’s camera first pans over the lotus growing in the large pond in which the tea house is situated. It then follows the crowds along one arm of the zigzag bridge linking the shore to the double-storied tea pavilion. The voiceover claims that the teahouse is reserved for senior citizens and their families (this was definitely not the case when I first visited Yu Garden in early 1975). The bridges connect it on one side to the Ming-era Yu Garden, and on the other to the old Temple of the City God 城隍庙. The sounds of the time are recorded with the same care with which the languid atmosphere of the teahouse is captured. The camera lingers on some of the sparse artwork on the walls of the pavilion; they include a large Mao slogan in golden lettering reading ‘Long Live the Great Unity of the Peoples of the World’ 全世界人民大团结万岁! and a poster from the film version of the Beijing Model Opera ‘Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy’ 智取威虎山. The voiceover tells us:

The atmosphere is strange: nostalgic and jovial at the same time. The recollections of the past mix with the confidence of the present.

The lens then loiters, seemingly transfixed by scenes of normal citizens of Mao’s China in casual and relaxed conversation. Customers drink out of small teacups, not the elaborate covered bowls or lidded tea mugs that are now common; they play with children, smoke, sip tea, smoke, chat… Nonetheless, the sounds are muffled, a low din that reflects the de rigueur atmosphere of a world that had survived the Maoist-Lin Biao ‘red terror’ that had by then reigned for half a dozen years. Through an upstairs window we catch sight of the last words of a popular Mao slogan: ‘Down with American imperialism and all reactionaries’ 打倒美帝国主义和一切反动派.

[Note: For these scenes in Chung Kuo, Cina, see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dz_VB4dkcRw at 12:55-14:45; and: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Azg-aFTxfIo at 00:00-3:30.]

In early 1974, Antonioni’s Chung Kuo, Cina was vociferously denounced in the pages of the People’s Daily. The paper’s commentator wrote in the over-blown prose favoured by Party hysterics at the time (and familiar to those inured to New China Newspeak):

More spiteful is Antonioni’s use of devious language and insinuations to suggest to the audience that the Chinese people are repressed, have no ease of mind and are dissatisfied with their life. In the scene of the teahouse in Shanghai’s Chenghuangmiao, he inserts an ill-intentioned narration, ‘It is a strange atmosphere’, ‘thinking of the past, but loyal to the present’. He uses the phrase ‘loyal to the present’ but means just the opposite. Actually he is implying that the Chinese people are forced to support the new society but do not do so sincerely or honestly. Does not Antonioni again and again suggest that the Chinese people are not free?

[Note: See the booklet by the Renmin Ribao Commentator, A Vicious Motive, Despicable Tricks—A Criticism of M. Antonioni’s Anti-China Film China, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1974. The Chinese original was published by People’s Daily on 30 January 1974.]

***

The Tea Issue of China Heritage Quarterly

Guest Editor: Daniel Sanderson

Table of Contents

History

- A Very Short History of Tea in China, by Marco Ceresa

- Tea in Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopædia

- Tea Jesuitica, by Jeremy Clarke, SJ

- The Tea-plant of China, by Robert Fortune

- Far-famed Sung-lo-shan 松蘿山, by Robert Fortune

道: Invented Traditions

- Aesthetics and Emotion in Taiwanese Tea Culture, by Scott Writer

- A Quintessential Invention, by Loretta Kim 金由美 and Lawrence Zhang 張樂翔

景: The Settings

- The Gentle Art of Tea Drinking, by John Calthorpe

- All the Tea Under Heaven, by Charlene Wang 汪晓宁

- The Eternal Green, by Jeff Fuchs

- The Tea Horse Road and the Politics of Heritage, by Gary Sigley

聚: Coming Together

- On Tea and Friendship, by Lin Yutang 林語堂

- Old Min’s Tea 閔老子茶, by Zhang Dai 張岱

- Tributes to a Tea Drinker: Wang Shih-shen’s 汪士慎 ‘Asking for Snow Water’ 乞水圖 by Alfreda Murck

- Ways that are Dark: Taking Tea, by W. Gilbert Walshe

- Tea People Talk Tea, by Zhou Zuoren 周作人 et al.

- A Tea Addict’s Journal, by Lawrence Zhang 張樂翔

具: Accoutrements

- Tea Utensils Illustrated 茶具圖贊, by The Old Man Who Examines the Usages of Peace 審安老人

- The Sophisticate’s Guide to Tea, by ‘hetao’

- Cooking with Tea, reflections and a recipe by Fuchsia Dunlop

- Tea Drinking and Ceramic Tea Bowls, by Li Baoping 李宝平

席: The Scene

***

The Xi Jinping Restoration — When Two Plus Two Makes Five

A certain country was under the rule of a mad and blood-thirsty tyrant. The fundamental axiom of the official ideology was “two plus two makes six.” Everyone lived in a state of permanent terror. Eventually the tyrant died and was succeeded by another one not as mad and not as strong. Some readjustments had to be made. It was proclaimed that the fundamental axiom would henceforth be “two plus two makes five.” This provoked a great commotion in all intellectual circles. A brilliant young mathematician was moved to rethink the entire issue by himself. After many months of feverish research he discovered that, in fact, “two plus two makes four”! Greatly excited, he wanted to publish his discovery when, early one morning, two men in gray raincoats knocked at his door and asked him softly: “What are you up to, Comrade? Do you really wish to return to the time when two plus two made six?”

***

David Rennie took up the role of The Economist’s Beijing bureau chief in May 2018, just as the People’s Republic of China was experiencing the full-blown effects of what we call the Xi Jinping Restoration 習近平中興. The era in which ‘two plus two makes four’ gave way to the older, fundamental axiom that ‘two plus two makes five’.

Having previously worked in the Chinese capital as a foreign correspondent for the Daily Telegraph (from 1998 to 2002), during his second tour, which came to an end in August 2023, Rennie confronted a much-changed landscape. It was a decade since Xi Jinping had tentatively revealed the style of the ambitious autocrat — first with the revival of Maple Bridge-style policing, under the rubric of the Pacify Beijing Action Plan, in the lead up to the Summer Olympics in August 2008, and then with his heavy-handed management of the Olympic Torch Relay.

Six months before Rennie launched his Chaguan/Teahouse column, Beijing’s spurious legislature had revised the Constitution granting Xi Jinping what, at the time, we called ‘terminal tenure’. Writers like Lee Yee, a veteran political commentator in Hong Kong, and Xu Zhangrun, a fearless academic at Tsinghua University in Beijing, also warned of what lay ahead. As we had noted when we launched the series Watching China Watching in January 2018:

Xi Jinping is only the latest in a long line of imperial pretenders whose hands are on the levers of power in what is, as Simon Leys observed, a gang-like state (see Peking Duck Soup). Like Mao, Xi is both master of and servant to empowering and stifling traditions. Whether he is described as an emperor or a CEO, we argue that as the head of China’s party-state-army Xi has not only become the Chairman-of-Everything and Chairman-for-Life but, since the Nineteenth Party Congress of October 2017, he is also Chairman of Everyone 黨政軍民學 and Chairman of Everywhere 東南西北中. With Wealth and Power backing up such titular immodesty, comparisons of Chairman Xi with Mao Zedong, or even with traditional emperors like Qianlong — he went so far as to fashion himself as a chakravartin चक्रवर्तिन्, a universal, ‘wheel-turning ruler’ — may prove to be inadequate.

The centuries-old rumour mill of China’s ruling class had also effectively been silenced by harsh restrictions and threats of punishment. As the commentator Feng Chongyi put it, ‘Xi and his Claque rely on the dark code of omertà, one typical of this Communist-style mafia.’ Soon, Hong Kong, a territory that offered a singular window on China and which had long enjoyed an open media and academic freedom was silenced by a security law imposed by Beijing.

There was a return to militant authoritarianism, the politicisation of society, pervasive censorship and repression. Xi’s preference for statism was gradually undermining the economic ebullience of earlier decades and bureaucratic desuetude was spreading. Online China, although heavily policed, proved to be rambunctiously resilient. Just as economic actors exploited every opportunity, writers, commentators, academics and rogue wits created a ramshackle Virtual Teahouse of their own.

David Rennie’s Chaguan column was written in the style of the English essay, a centuries-old form that combines keen observation with human detail. To this he added a reporter’s insight and an understated lyricism. His columns — 220 published over six years — displayed a deep affection for and empathy with the world he describes while maintaining the probity and inquisitiveness of a seasoned journalist.

***

I’ve been enamoured with essay form, or short prose compositions, ever since reading William Hazlitt in my high school English class. Francis Bacon and Charles Lamb were, of course, also on the curriculum, but it was Hazlitt who left the greatest impression. Later George Orwell’s collected essays would be a constant companion and even before I began studying Chinese formally, I had encountered Lin Yutang’s idiosyncratic English essays on culture and history. Long before I saw the revived Teahouse on the Beijing stage, mentioned earlier, I had worked through some of Lao She’s essays, reprinted in the Hong Kong media and introduced to our Chinese class by Pierre Ryckmans.

The Chinese Essay — 散文 、小品文 、雜文、隨筆 — has featured in my work, and my translations, ever since (for some recent examples, see Eating Watermelon with Wu Guoguang and Li Chengpeng’s China Has No ‘New Year’). For some fifteen years, I even tried my hand at writing Chinese essays, and, since its inception in 2016, the essay form has dominated the virtual pages of China Heritage.

In An Artistic Exile, I echoed Lin Yutang’s claim that the Essay is among the most significant literary achievements of modern Chinese literature. Lin himself perfected a style of essay writing, both in Chinese and English, and a decade before he enjoyed international renown he championed a form of the English-language essay adapted to modern China in the pages of The China Critic, the weekly journal that he published from 1928. In the 1930s, Lin launched a series of popular literary journals that he promoted the essay form in all of its variety. He told readers that essays were so versatile that they ‘can be discursive, just as they can give voice to deeply felt sentiment.’ ‘Essays’, he continued:

limn the varieties of human experience as readily as they record the goings on of the world. They weave together the seemingly trivial while also being able to embrace the vastness of our existence. There are unconstrained in subject matter and, above all, they are a vehicle for self-expression and casual reflection of a kind familiar in the West. The essay marries the deeply felt to the incisive, creating thereby a particularly modern literary form.

蓋小品文,可以發揮議論,可以暢洩衷情,可以摹繪人情,可以形容世故,可以札記瑣屑,可以談天說地,本無範圍,特以自我為中心,以閒適為格調,與各體別,西方文學所謂個人筆調是也。故善冶情感與議論於一爐,而成現代散文之技巧。

I can offer no higher praise than to say that many essays in David Rennie’s Chaguan series belong in a tradition that straddles two cultures.

— The Editor

***

Chaguan —

The Economist’s China column

It is named after traditional teahouses, where far more than hot drink once flowed

13 September 2018

Given his love of Chinese teahouses, Mr Yang, a retired academic from Chengdu, was born in the right place at a terrible time. Within living memory his home town, the capital of Sichuan province, had boasted more than 600 teahouses, or chaguan. Some were famous for storytellers or opera. Others welcomed bird-lovers, who liked to suspend their pets in cages from teahouse eaves to show off their plumage and singing. Some served as rough-and-ready courtrooms for unlicensed lawyers (to “take discussion tea” was to seek mediation). One place might attract tattooed gangsters, another intellectuals. Wang Di of the University of Macau, a scholar of teahouses, cites an old editor who in the 1930s and 1940s ran his journal from a teashop table.

Mr Yang, who declined to give his full name, favours Heming teahouse, a lakeside tea garden where patrons may spend hours in bamboo armchairs, reading newspapers, munching melon seeds or paying a professional ear-cleaner to rootle away with metal skewers. But he has known more dangerous times. Soon after first visiting the teahouse as a child in the 1960s, such businesses were targeted when young, fanatical Red Guards roamed his city during the Cultural Revolution. “Back then everyone was busy chanting about revolution on the streets—this type of culture was criticised,” he recalls. Slow tea-sipping was called time-wasting, vain and bad. Maoist zealots closed teahouses.

This was not their first taste of repression. Before Communism, Chengdu endured iron-fisted rule by the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek. Despots with a bossy, scoutmasterly streak, the Nationalists issued dozens of orders to stamp out bad teahouse habits. Managers were told to report clients spreading political rumours. Bawdy songs were banned. Teahouses were told to expel itinerant barbers (who did sometimes drop hair clippings in other patrons’ teacups, it is true). During the war with Japan, teahouses in Chengdu were ordered to display Nationalist flags, slogans and leaders’ portraits, and to inscribe approved news headlines on blackboards. In 1948 Sichuan’s governor demanded teahouse controls to “regulate people who do not follow rules” and “turn uselessness into usefulness”.

Teahouses had been little safer during the first decades of the 20th century, when warlords had brought terror to cities, or even earlier in the dying days of the final imperial dynasty, the Qing. The author Lao She, who in 1956 charted a Beijing teashop’s woes over a half-century in his play “Teahouse”, drew on life when he had the establishment’s manager pin up signs pleading “No talk of state affairs”, or when he showed grey-gowned secret police arresting customers for questioning the government.

That teahouses managed equally to enrage Red Guards, Nationalist police chiefs and desiccated imperial mandarins might be reason enough to cherish them, and to name The Economist’s new China column “Chaguan” in their honour. But teahouses are more than fine places that attracted the right enemies. In their heyday, when some city streets might have boasted half a dozen, they were places to relax, do business, gossip and exchange ideas, both lowbrow and highfalutin. Some teahouse litigators were crooks, writes Qin Shao of the College of New Jersey, another teahouse historian. But at its best, teashop mediation with crowds hearing every word, could expose and shame local bullies, offering a rough sort of accountability.

Like users of social media today, teahouse patrons loved tales of corruption, broken promises and immorality among the mighty. Some were false. Others contained enough truth to help explain why officials raged at them. A stubborn, indignant, often mocking resistance to finger-wagging propaganda is as much a Chinese tradition as deference to authority.

Officials have spent more than a century vowing to modernise China, promoting reforms that—certainly in the past 40 years—often demand the world’s admiration. Chinese leaders argue that their vast country cannot risk the morale-sapping confusion that might be sown by a free press, independent courts or even civic groups with the right to criticise official wrongs. Anyone calling for democratic freedoms is attempting to infect China with dangerously alien, indeed Western notions, officials assert.

Yet such claims look questionable, not to mention self-serving, after reading historic accounts of teahouses and the unmistakably democratic impulses that sometimes moved customers. Even signs reading “No talk of state affairs” can be read as ironic symbols of protest against the suppression of free speech, as Wang Di has written. Similar democratic impulses can still be seen all over China, whenever citizens note that powers are being abused, mistakes covered up or that life seems unfair or absurd.

Teahouses are unlikely to boom again in Chengdu. Youngsters at Heming spoke of making time to “chill for the afternoon”, as they are usually too busy. Tastes change. This writer was on a first China posting two decades ago when Starbucks opened its inaugural shop there, in Beijing. The chain plans to have 6,000 outlets in China by 2022, with one opening every 15 hours.

Orders for the doctor

But teahouses are more than places to buy a drink. They represent something precious: a space that is public yet not state-controlled, where citizens may speak, listen and be moved, find work, do deals or seek redress, or simply idle for a while. Today that spirit can be found online or in the gig economy, despite government controls. It is seen when citizens’ groups report injustices, displaying a complex mix of distrust and trust in officials, whose help they seek while doubting what it can achieve.

“Chaguan” aims to cover that China, writing about society, the economy and culture. Long ago, in a spirit of teasing respect, teahouse waiters were dubbed “tea doctors”. To be a tea doctor, patiently serving while patrons talk, seems a good ambition for a China columnist. Stoke the stove, then. To work.

Source:

- The Economist’s new China column: Chaguan, 13 September 2018. (Links added by China Heritage)

***

***

China’s new age of swagger and paranoia

It wants to be a “strong tiger” not a “fat cat”

28 August 2024

Should the world admire or fear China’s model of governance? Since this column was launched in September 2018 that question has become more urgent, as Xi Jinping declares it time for China to “move closer to the centre stage” of world affairs.

Today’s China welcomes other countries to follow its “pathway to modernisation”. Mr Xi, the most powerful Chinese leader in decades, calls his one-party model efficient, equitable and dignified. In case foreigners miss his coded message—that competent government, equality and order matter more than freedoms—officials boast of “two major miracles” that shaped China’s rise, namely “fast economic development and long-term social stability”.

During six and a half years in Beijing, your columnist has watched China’s swagger divide the world. Most importantly, Sino-American relations have collapsed, raising the prospect of a globe divided into rival camps, even as other countries insist that they have no desire to pick sides. Wary but profitable coexistence has turned into a contest for primacy in the 21st century.

That confrontation is more alarming because logic guides each side. American leaders have solid grounds for alarm. By its actions and words, Mr Xi’s China reveals an ambition to be so powerful by mid-century that no other country on Earth will dare to thwart or defy it. To achieve that status, China is bent on reshaping the world order from within, using its heft in such forums as the United Nations to challenge, redefine or discredit any norms and rules that might curb its rise.

For their part, Chinese officials and scholars have every reason to fear and resent the new bipartisan consensus in Washington. They are right to suspect that American leaders (from both main parties) are trying to slow or block their country’s progress in any field of endeavour—whether technological, economic or geopolitical—that might imperil American national security. Chaguan has heard senior American officials frame this strategy as a simple question: why would we let American cash or American technology strengthen China’s military or national-security apparatus?

That approach is, of course, intolerable to China. Your columnist has not forgotten the metaphor offered by a leading Chinese scholar over dinner in Beijing. America is only willing to let China become a “fat cat”, producing harmless consumer goods, he ventured. But, he added, “it is natural for a country to want to become strong, like a tiger”. Put bluntly, China and America are two giant powers with mutually incompatible ambitions.

To many Chinese officials, scholars and citizens, their country has never been so impressive. At the same time, China feels criticised as never before by America and other liberal democracies. China has not changed, runs a frequent complaint in Beijing, it merely grew successful and strong. Clearly a querulous, declining West is too racist to tolerate an Asian power as a peer competitor.

The latest global opinion survey by the Pew Research Centre finds just one rich country, Singapore, where most adults approve of China. But views of China are much warmer in low- and middle-income countries, notably in Africa and South-East Asia. Ambassadors from the global south call China’s emergence from deep poverty an inspiration. They thank China for offering the world new markets, investments and infrastructure, without the “colonial-style” lectures beloved of Western powers.

Some of those same envoys grow impatient when they hear European or American counterparts criticise China’s iron-fisted treatment of ethnic minorities, or condemn China’s defend-Russia-blame-America approach to the war in Ukraine. What about American rights abuses in Iraq and Afghanistan, Chaguan has heard Latin American and Middle Eastern ambassadors ask? What about America’s arming of Israel in Gaza? Beneath such questions lie real resentments that China stands ready to exploit. During the depths of the pandemic, Chaguan was summoned to a government guesthouse for a one-on-one conversation with a senior Chinese official. Western countries talking about universal values are like colonial-era missionaries telling other countries which god to pray to, was the official’s message.

Because the world is divided in its perceptions of China, that has fuelled another dynamic. Over the past six years, Chinese leaders have become increasingly unwilling to accept foreign scrutiny of their country. Not long ago, Chinese reformers quoted foreign critics to help them push for change. Now the reformers do not dare. In Mr Xi’s China, even constructive foreign criticism is called a ploy to hold China down.

Your lonely columnist

The siege mentality of China’s rulers goes beyond a dislike of foreigners with complaints. Mr Xi has told diplomats, scholars and state media to be more confident, and to defend China with home-grown measures of success. In today’s China it is unpatriotic even to engage with foreign arguments about what makes for good governance, wise economic management or the rule of law.

Reporting from China has become a shockingly lonely business. Too many foreign correspondents, notably from America, have been expelled or pushed out by harassment. When others left voluntarily, their news organisations struggled to obtain new visas. The Trump administration bears blame for expelling scores of Chinese reporters, giving officials in Beijing a perfect excuse to retaliate. But the numbers are stark. During Chaguan’s current posting, the New York Times went from ten foreign correspondents in mainland China to two at present, the Wall Street Journal from 15 to three, and the Washington Post from two to zero.

Chinese anger at foreign criticism has its roots in an argument about legitimacy. As long as China’s economy was roaring ahead, and each year saw its cities fill with gleaming new skyscrapers and high-speed-train stations, Communist Party bosses could claim “performance legitimacy”, to use the jargon of political scientists.

To be clear, China’s modernisation is worth boasting about. China has not just become wealthier. Newly paved roads have saved mountain villages from being cut off by heavy rains. In every rural county, highway tunnels and bridges have reduced journey times by hours. Urban landscapes have been transformed. Air and water pollution have declined dramatically. Across China on a typical evening, newly built parks and cleaned-up rivers attract strolling families or pensioners who gather to play Chinese chess or practise tai-chi. Cities are more orderly and street crime rarer. Ask middle-aged Chinese whether they have better lives than their parents, and they answer yes almost in unison. Others note the weakening of cruel traditions, such as the migrant worker in Chongqing who recalled that, in the hometown of his youth, women could dine only after their male guests had eaten their fill.

As China’s economy slows, however, the Chinese public’s mood has soured. The party has duly adjusted its claims to rule. To those arguments about performance, leaders have added assertions that China has the ideal political system. These claims emphasise the country’s second self-styled miracle, namely its stability. American democracy is in a “disastrous state”, officials say. They accuse Western politicians of heeding voters only at election time. They call China a “whole-process people’s democracy”, in which technocrats (purportedly kept honest by internal discipline and the unending anti-corruption campaigns of the Xi era) tirelessly study and address the needs of the many, not the few.

China is not a democracy. It is, at best, a country run in the interests of the majority, as defined by an order-obsessed party. Covid-19 tested this utilitarian model to breaking-point. The pandemic was days old when Chaguan caught an almost-empty flight to Henan province in January 2020. His taxi passed villages closed by fresh barricades of earth, guarded by old men with red armbands. At last he reached Weiji, the final village before Hubei, a province of 58m people sealed to the world after the disease first emerged in its capital, Wuhan. Asked whether they supported strict pandemic controls, villagers scolded your columnist. “Chinese people really listen to the government” and will put the common good ahead of their self-interest, said one man. “It’s different from you Western countries.”

Hundreds of millions of Chinese proved that villager right, staying at home for weeks, often without pay, to break covid’s chains of transmission. Given China’s weak health system, their sacrifices saved untold lives. Over the next two years, simple arithmetic explained public tolerance of zero-covid controls. At any given moment, the system imposed pain on those unfortunates who lived in locked-down areas, or who had been hauled off to quarantine camps. But most Chinese, most of the time, felt safe.

Then the highly contagious Omicron variant reached China. Ever larger numbers faced lockdowns, including Shanghai’s 24m residents. In late 2022 protests broke out across an exhausted country. Abruptly, controls collapsed. A million or more died, many of them unvaccinated old people. The precise toll is secret.

China is declaring its own citizens traitors if they question the party’s model of governance, and calling all foreign scrutiny a form of attack.

Returning to Henan in January 2023, this columnist found hospitals that lacked painkillers and met doctors banned from recording covid as a cause of death. The system was to blame. Throughout 2022 scientists had urged leaders to vaccinate the old, stockpile drugs and prepare an exit from zero-covid. Alas, Mr Xi’s policy could not be questioned, or order jeopardised, ahead of a party congress in October at which he was handed a third term.

China’s version of utilitarian rule offers no protections to individuals who fall on the wrong side of the majority-minority line. Worse, that line can move without warning. In Xinjiang Chaguan saw mosques closed or demolished after religious rules were tightened. He reported on a sterilisation campaign imposed on Uyghur women after 2017, when their high birth rates were declared a threat. In Guangdong he wrote about female workers whose bosses cheated them of pension contributions. An algorithm spotted the women’s online talk of petitioning the authorities. Police raided their dormitory, humiliating them with strip searches. Though legal, their petition plans challenged social stability.

China’s crushing of Hong Kong’s freedoms, after anti-government protests in 2019, follows a majoritarian logic. Mainland officials scorned the idea that a territory of 7.5m people could imagine it had the right to defy a motherland of 1.4bn. They accused the cia of planning the demonstrations. The truth is sadder: there was no plan. Chaguan met youngsters who could not explain how confronting China would end well, but who wanted to protest while they could.

Most alarming, leaders increasingly emphasise one last form of legitimacy, which brooks no appeal at all. This is a claim to rule based on “5,000 years of unbroken Chinese civilisation”, synthesised with a dose of Marxism. Under Mr Xi, the party presents itself as the “faithful inheritor” of all that is virtuous and wise in Chinese history. “The fact that Chinese civilisation is highly consistent is the fundamental reason why the Chinese nation must follow its own path,” Mr Xi has declared. And because Chinese civilisation is unusually uniform, Mr Xi adds, different ethnic groups must be integrated and the nation unified: code for imposing the majority-Han culture on all, and for taking back Taiwan.

A new host at the teahouse

Nothing worries Chaguan more than this ethno-nationalist drive. China is declaring its own citizens traitors if they question the party’s model of governance, and is calling all foreign scrutiny a form of attack. More than ever, pluralism is seen as a security threat. When feminists, environmentalists or religious teachers are detained, they are questioned about contacts with foreigners and treated as potential spies. If this inward turn continues, it may give some admiring countries pause. China is willing to be praised and copied, but not doubted in any way. This is not a magnanimous moment in its history. The future may be still darker.

This reporter has written 220 Chaguan columns, from all but one mainland province and region (a permit to visit Tibet was not forthcoming). That access to China’s people, from packed sleeper trains to the halls of power in Beijing, was a privilege and a necessity. When his successor receives a resident press visa, the Chaguan column will return.

***

Source:

- China’s new age of swagger and paranoia, The Economist, 28 August 2024

***

Ways that are Dark: Taking Tea

W. Gilbert Walshe, M.A.

Editorial Secretary of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian

and General Knowledge Among the Chinese etc.

The Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge Among the Chinese was founded in Shanghai in 1887 by British and American Methodists to introduce both Christian and scientific concepts to China. To achieve these goals, members undertook a range of activities, including translation projects. Members of the Society included Young John Allen and Timothy Richard, both of whom had considerable impact on late-Qing reformists.

Ways that are Dark first appeared through Kelly and Walsh in Shanghai in 1890. Written to facilitate the propagation of the mission of the Society it went through eleven editions up to 1924. The title of the book is a reference to a line in the poem The Heathen Chinee, written by Bret Harte in 1870 and meant as a satire on anti-Chinese attitudes prevalent on the Californian goldfields at that time. Unfortunately, widely misinterpreted and highly popular, the poem only served to entrench racist views.

By way of contrast, Walshe’s book offers a not unsympathetic introduction to elite Chinese mores. As the author states, it was written ‘at the request of the Mid-China Church Missionary Conference for the guidance of missionaries newly arrived in China, it being felt that a better acquaintance with Chinese social methods might prevent many unfortunate blunders and much mutual misunderstanding between the missionaries and the Chinese.’ After referring to Harte’s controversial poem, Walshe continues:

So far from attempting to deride or belittle the old-established and, in many cases, admirable institutions of the Chinese people, my special object is to solicit a more particular attention to the usages of Chinese polite society, and to bespeak a more sympathetic and appreciative recognition of their social conceptions than at present obtains in some—I might venture to say, in many quarters.

[Note: Walshe, Ways that are Dark, pp.11 & 12.]

Many of the formalities described in Ways that are Dark persist in various guises in contemporary behaviour—or at least they are widely recognized and appreciated when understood. Minor modifications, including paragraph breaks and Hanyu Pinyin romanisation, have been made to accommodate the modern reader.

— The Editor

***

Comportment when Taking Tea

Before the company is actually seated the host places cups of tea on the tea-poy (茶几) at the side of each seat, the guest putting both hands to his head in acknowledgement; and when the servant places the cup for the host, the guest makes a feint of helping to put it down with both hands, and the host rises slightly from his seat with a gesture of remonstrance, saying: ‘I am not worthy’ (不敢). The tea is not drunk at once, but conversation begins.

Before the company is actually seated the host places cups of tea on the tea-poy (茶几) at the side of each seat, the guest putting both hands to his head in acknowledgement; and when the servant places the cup for the host, the guest makes a feint of helping to put it down with both hands, and the host rises slightly from his seat with a gesture of remonstrance, saying: ‘I am not worthy’ (不敢). The tea is not drunk at once, but conversation begins.

The visitor, if acquainted with the host may say, ‘I am come again to trouble you’ (近日又来吵擾), the host replying, ‘You are too polite’ (客氣勞駕). If a new arrival is present, the older visitor may then say, ‘Mr. So-and-so has lately arrived, and has come to pay his respects’; and the host replies, ‘I am not worthy’. If there is any business to be discussed it may then be introduced, and some polite references may be made to the fact of His Honour’s kind protection of the foreign resident in his district, etc. One or two general cautions may here be suggested with reference to the bearing of the foreign visitors:

- It is very important that visitors should ‘look pleasant’, as the photographers say, and should smile affably, but not too effusively, when addressing the host or replying to his questions.

- The voice should not be too loud, but gently modulated.

- The wonders of foreign mechanical contrivances, and other achievements, should not be too blatantly advertised; and, in fact, they had better be kept in the background unless the subject is introduced by the host.

- Criticism of Chinese methods, and especially ‘little weaknesses’ of the officials, should not be indulged in—this would be extremely ‘bad form’.

- When the speaker refers to himself he should avoid, as far as possible, the personal pronoun, and should speak of himself as ‘the brother’ (兄弟). The second person should never be used in addressing the host, but he should be styled ‘Your Excellency’ (閣下), or, if of any rank above that of district magistrate, he may be called ‘Great Man’ (大人). In referring to China the visitor should call it ‘Honourable Kingdom’, and refer to his own country as ‘Mean Kingdom’ (貴國,敝國).

- An official call should not be greatly prolonged, as the magistrate is (politely) supposed to be immersed in affairs of state, and an excuse for a short visit is easily supplied by remarking that His Honour is doubtless very much occupied, etc.

- It is not polite to look the host ‘right in the eye’, but to fix the eyes upon his breast when addressing him, and only occasionally look him in the face—the appearance of excessive boldness is thus avoided.

- In conversing with comparative strangers great care should be observed in order to avoid indiscretions; whilst in the company of familiar acquaintances even greater care is necessary, lest one should be led to speak inadvisedly; and it should be remembered that the hasty utterance, though harmless enough in the intention of the speaker, may be distorted beyond recognition when repeated by careless or designing hearers.

- If it should happen that the host is acquainted with English, the conversation should be conducted in that language, and a good many of the ceremonial observances may be thus avoided.

If the host thinks sufficient time has been occupied, he may say, ‘Please take your tea when it suits you’ (随便請茶). This is a signal to depart. Or if the guest is anxious to go, he may take the initiative and invite the host to drink, by saying, ‘Please (take) tea’ (請茶). If, however, the guest is invited to partake of tea before his business is satisfactorily arranged, he may overlook the hint for the nonce; but if the official should order the attendant to bring in fresh tea (换茶), this must be taken as a signal which cannot be disregarded, and the guest must either finish what he has to say without further circumlocution, or take his leave without delay.

If the host thinks sufficient time has been occupied, he may say, ‘Please take your tea when it suits you’ (随便請茶). This is a signal to depart. Or if the guest is anxious to go, he may take the initiative and invite the host to drink, by saying, ‘Please (take) tea’ (請茶). If, however, the guest is invited to partake of tea before his business is satisfactorily arranged, he may overlook the hint for the nonce; but if the official should order the attendant to bring in fresh tea (换茶), this must be taken as a signal which cannot be disregarded, and the guest must either finish what he has to say without further circumlocution, or take his leave without delay.

In some cases, however, it will be evident that the host does not intend to hasten the guest, but merely to consult his convenience by replacing the tea which has grown cold; this will be evident when the host himself is engaged in a long speech, and gives the order for fresh tea before he has exhausted his topic. In such cases the guest’s own perception will be the best guide, as no hard-and-fast rule can be laid down; but it will be well to remember that in ordinary cases the order for fresh tea is intended as a hint to bring the interview to a close.

When about to drink tea the guest take up his cup with both hands, and raising it to his lips at the same moment as his host, sips once or twice in concert with him, and puts down his cup when he does. When the guest has tasted his tea he should say, ‘I have put you to trouble’ (叨擾), or some other suitable phrase, and rise up to take his departure.

Host and guest salute each other with a gong [躬 ‘bow’]—meanwhile the servant will have called the chair-bearers—and the host conducts his visitors through the several gateways to the place where their chairs are awaiting them, the guests going first and making a polite protest at each doorway against the host accompanying them any further, saying, ‘Please stay your steps’ (請留步), or, ‘I am unworthy’; the host replying, ‘This is only right’ (應該), or, ‘You are too polite.’ On reaching the entrance, where the chairs are stationed, both host and guest make a gong, the visitor steps sideways over the pole of his chair (which is held down for the purpose by one of the bearers), taking care that he does not turn his back to his host in so doing; and just before taking his seat, he makes a final gong, saying, ‘We shall meet again’ (再會). He then backs into his chair and is borne off.

***

***

Source:

- W. Gilbert Walshe, Ways that are Dark, Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh, 1890, pp.50-54, reproduced as Taking Tea, in China Heritage Quarterly

***

Keep Politics Out of It!