Spectres & Souls

The following essay by Simon Leys was published in early 1987, in the wake of student demonstrations that, having originated in Hefei, the provincial capital of Anhui, rocked Shanghai in December-January 1986. Protesters at over 100 universities in seventeen cities, outraged by high levels of inflation and evidence of runaway corruption and cronyism in the Communist Party, demanded media openness and substantial nationwide political reform. The Shanghai protests, which were among the largest and most widely reported, were eventually quelled by the party boss of the city Jiang Zemin who refused to countenance the students’ demands. He backed up his intransigence with brute police force.

Jiang’s deflection of the protesters’ demands and his decisive action, along with his subsequent relentless approach to demonstrators who took to the streets of Shanghai in support of the mass Protest Movement in Beijing from April to June 1989, enabled him to curry favour with Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun, the key economic overlord, in the long run. In the short term, however the presiding Party General Secretary, Hu Yaobang, was forced out of office in mid January 1987, and a number of prominent intellectuals — identified by Deng as progenitors of the student disturbance — were ousted from the Party and denounced.

The premier, Zhao Ziyang, duly replaced Hu Yaobang as head of the Party, even observers with only the most rudimentary appreciation of the treacherous political terrain that he faced, knew that Zhao was a marked man. In concert with his fellow ‘Eight Elders’ — the ruling gerontocrats of the Communist Party — Deng Xiaoping would elevate Jiang Zemin to the position of Party General Secretary in the stead of Zhao Ziyang, a more reform-minded leader who had sympathised with the student-led protesters in 1989, who was purged following the 4 June Beijing Massacre.

During this period, from 1987 to 1989, a rolling series of protests in the Tibetan Autonomous Region were also harshly suppressed by the party satrap, a man by the name of Hu Jintao. Again, Deng and his colleague approved of Hu’s unyielding response to all expressions of popular discontent, an important factor in him being helicoptered towards ultimate power in 2002, following Jiang Zemin’s retirement as the head of the Party and president of the Peoples’s Republic. (This was the only peaceful power transition since Mao took the helm in 1936, under murky circumstances. The Hu Jintao-Xi Jinping handover involved a vicious, if somewhat cloaked, power struggle between Bo Xilai and Xi Jinping. Circumstances and canny footwork saw the lackluster Xi rise over the shattered reputation of Bo, even as he purloined his rival’s policies.)

A quotation from the following essay by Simon Leys was used to preface ‘Bourgelib: 1979-1987, A Chronicle of Purges’, one of the four chapters that John Minford and I added to an expanded edition of Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience (Hong Kong, 1986) published in North America in 1988 (see Seeds of Fire, New York: Hill & Wang, 1988).

As we noted in our editorial note:

‘ “Bourgelib” [a New China Newspeak neologism of our invention] takes as its theme the latest of Mainland China’s political campaigns, the “struggle against bourgeois liberalization”. This is a process that Chinese leaders have declared will continue well into the next century. Its aim is to attack and denounce intellectuals, writers and artists who defy the leadership of the Party by indulging in any form of solipsism, or the culture of the self.’

— Seeds of Fire, 1988, pp.325-236

In light of the latest ‘revolution’ in Chinese politics, gratias Xi Jinping, this would appear to be a good time to share Leys’ observations with readers of China Heritage. After all, as Leys remarks: ‘it would be quite presumptuous to assume that what we wrote was read, and that what was read is still remembered.’ That holds as true for his coruscating prose as it does for our far more modest efforts.

***

‘Over One Hundred Years’ is a series of essays published by China Heritage to mark the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party. The series is included in China Heritage Annual 2021, the theme of which is ‘Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

8 September 2021

***

Related Material:

- Simon Leys, ‘The China Expert and The Ten Commandments — Watching China Watching (I)’, China Heritage, 5 January 2018

- Simon Leys, ‘Non-existent Inscriptions, Invisible Ink, Blank Pages — Watching China Watching (II)’, China Heritage, 7 January 2018

- ‘Peking Duck Soup — Watching China Watching (X)’, China Heritage, 23 January 2018

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Memory Holes, Old & New’, China Heritage, 29 May 2017

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘One Decent Man’, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018, vol.64, no.11 — Watching China Watching (XXVI)

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Supping with a Long Spoon—dinner with Premier Li, November 1988’, China Heritage, 10 December 2018

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘In Memoriam—Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys)’, China Heritage, 11 August 2021

- Xu Zhangrun with Geremie R. Barmé, interviewed by Matt Seaton, ‘The Refusal of One Decent Man’, The New York Review of Books, 21 August 2021

***

China’s New Math

Simon Leys

Some cultures have no history. They may be the happier ones, but it is hard to tell, since we usually forget to ask before destroying them. Some cultures have a linear history, like ours, for instance. We forge ahead with gusto and dynamism, we move forward faster and faster; only we are not too sure where exactly we are heading. Let us hope it is not into a brick wall or a black hole. Some, like China, appear to have a cyclical history. This simplifies the task for the historians. Yet if these idle bystanders enjoy watching the merry-go-round, it can in the long run produce some dizziness among its hapless passengers.

The editor of The New Republic asked me to comment on the latest events in the People’s Republic. Having already published too many books on these matters, at first I wished to decline his invitation; Chesterton, who had written much about Ireland earlier in his career, observed at the end of his life that he had nothing to say on the subject because he had nothing to unsay. However, we cannot always disappoint the expectations of our friends without providing at least a word of explanation. And it would be quite presumptuous to assume that what we wrote was read, and that what was read is still remembered.

The outline of the story is rather simple: the old Leader (whom foreigners generally consider to be a Humanist, a Poet, a Progressive, a Liberal, etc.) wants to get rid of the very man he had previously picked as his heir-designate. To provoke the downfall of his most trusted acolyte, he engineers civil disturbances by manipulating the wide-spread and permanent discontent of idealistic youths. These young people finally realize that they are being used, but when they attempt to make a stand on their own, it is already too late, and they are crushed. Order is being re-established by “killing one chicken in order to scare the monkeys.” The chicken is found in the cultural circles, since writers and artists are always expendable (you only need to keep a few domesticated specimens for the purpose of Cultural Exchanges and International Congresses; as for the rest, with communism on tap in every household, who needs culture anyway?). While prominent intellectuals are duly gagged and ritually humiliated in the big cities, the merriment takes a more casual style in remote provincial corners that are conveniently sheltered from outsiders’ eyes. There, local officials eager to show their zeal, send a few cartloads of their own private enemies to the grounds.

Such is the basic plot. It needs only to be told once: erase all the individual names, fill in the blanks with new names, and every ten years or so the old story will be ready for recycling.

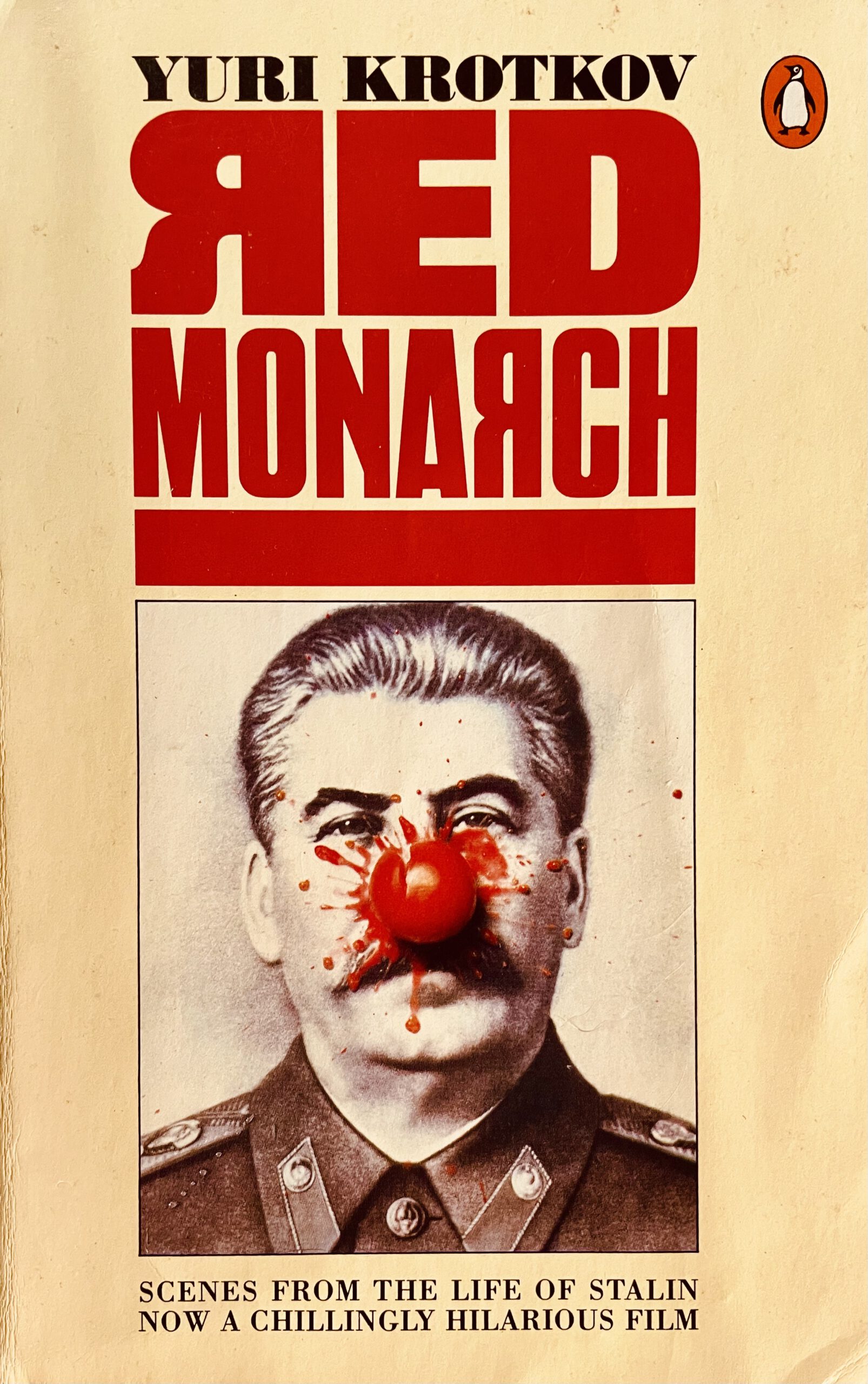

A “China Expert” disagreed with my views. “No, he told me, China is actually evolving, and not merely revolving however slowly and painfully. There are recurrent setbacks, it is true, but if the graph of these zigzags is seen from a suitable distance (which the victims cannot usually reach, I grant you) it will become apparent that the country is unmistakably inching forward. Look at the Soviet Union, for example. There are some achievements from the Khrushchev era that remain irreversible, and the same will be true for Gorbachev. A return to pure Stalinism—or to pure Maoism—is now inconceivable.” He was right, of course. Yet his Soviet reference reminded me of a story told by Yuri Krotkov in his Red Monarch. It went like this: A certain country was under the rule of a mad and blood-thirsty tyrant. The fundamental axiom of the official ideology was “two plus two makes six.” Everyone lived in a state of permanent terror. Eventually the tyrant died and was succeeded by another one not as mad and not as strong. Some readjustments had to be made. It was proclaimed that the fundamental axiom would henceforth be “two plus two makes five.” This provoked a great commotion in all intellectual circles. A brilliant young mathematician was moved to rethink the entire issue by himself. After many months of feverish research he discovered that, in fact, “two plus two makes four”! Greatly excited, he wanted to publish his discovery when, early one morning, two men in gray raincoats knocked at his door and asked him softly: “What are you up to, Comrade? Do you really wish to return to the time when two plus two made six?”

— The New Republic, 2 March 1987