Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance (XVII)

In this season of anniversaries, and as the ‘May Fourth Spirit’ of patriotism, democracy, science and student activism is claimed by Communists and independents alike, we would encourage readers to consider Homo Xinensis — ‘Xi Jinping-era Humankind’ — the most recent version of the ‘New Socialist Person’ that has been inculcated by the Communist Party since the late 1930s.

It did so on the basis of the new orthodoxies of a narrow patriotism, intellectual utilitarianism, academic pragmatism and political ambition that grew directly from the ruins resulting from the frenzied iconoclasm of the New Cultural Movement and May Fourth era (c.1917-1927). This then is no aberration. It is, as we argue in Translatio Imperii Sinici, our China Heritage 2019 Annual, part of the century long realignment of what the academics Jin Guantao and Liu Qingfeng identified as an ‘Ultra-stable System’ resulting from, and repeatedly subject to an inertia decided by an integrated and holistic approach to politics, ideology, social behaviour and cultural practices. It is one that strains to reaffirm Unity of the Way 道統, Intellectual-Cultural Legitimacy 正統 and Political Integrity 法統.

The reassertion of these forces is not just a happenstance result of personal political hubris — although noteworthy individuals have played a disproportionate role in creating China’s present circumstances — for generations of patriots, thinkers and activists devoted to the search for Chinese Wealth and Power in the modern world have supported a national unity, and various kinds of conformity that has been forged regardless of the personal cost, social stability pursued irrespective of the traumas and tragedies that have resulted and the affirmation of the role of State Will even when that demands harrowing self-abnegation. This ‘May Fourth Tradition’ then is no mere Communist Party confabulation or just another case of a hijacked historical incident. With the hindsight afforded by the events of the last century, perhaps this 2019 year of historical anniversaries and dark commemorations can offer new opportunities to question and reconsider old conclusions.

***

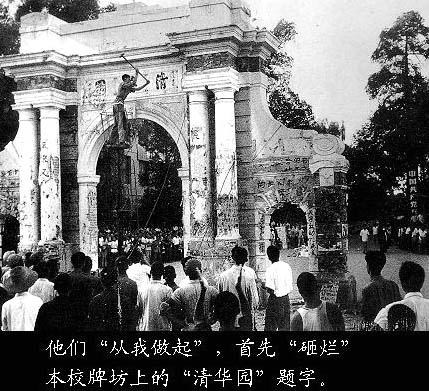

The following essay by Xu Zhangrun on the new kind of student-apparatchiki at Tsinghua University foreshadows by just over a year ‘Mourning Tsinghua 哀清華’, a memoir in which the respected Tsinghua graduate Zi Zhongyun 資中筠 observed that:

… even back then [in the early 2000s] people were saying that nowadays Tsinghua was a place that ‘brings together the outstanding talents of the world only to ruin them’. By ‘ruin’ people meant that Tsinghua had become a place suffocated by bureaucratic aspiration, an institution that twisted keen young minds into learning how to worship at the altars of big bureaucrats, starting with the president and faculty members. How could students possibly focus on their studies in such an environment? In other ways, it isn’t even accurate to claim that Tsinghua ‘assembles the outstanding talent of the world’. In the past, people believed that only the most intelligent and studious young men and women could possibly get in to Tsinghua. But, these days, so many ‘academic bootcamps’ promote themselves with claims about how many of their graduates have made it into Tsinghua or Peking University. With that kind of pre-college inculcation, young people are ‘ruined’ long before they even step onto the campus. The fact of the matter is that the quotient of genuine talents drawn to study at Tsinghua has significantly dropped off.

— Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, ‘My Tsinghua Lament’,

China Heritage, 3 April 2019

Universities that nurture more student-careerists than any other kind are hardly unique to the People’s Republic of China. Corporatised institutions of higher learning worldwide annually boast legions of graduates of the kind identified both by Xu Zhangrun below, and by Zi Zhongyun. For more on this subject, see An Educated Man is Not a Pot 君子不器, China Heritage, 2017.

***

‘I Reject the Blandishments of This Era’ 我拒絕與這個時代和解 was originally published in March 2018. It is included here as the latest chapter in our series ‘Xu Zhangrun versus Tsinghua University — Voices of Protest & Resistance’.

My thanks to Reader #1 for finding the time to read over the draft translation, correct typos and make a number of insightful suggestions.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 May 2019

***

Further Reading:

- Geremie R. Barmé, ed., An Educated Man is Not a Pot 君子不器, China Heritage, 2017

- Geremie R. Barmé, May Fourth at Ninety-nine — Watching China Watching (XXII), China Heritage, 4 May 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis, China Heritage, 31 August 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis Ascendant, China Heritage, 16 September 2018

- The Editor and Others, Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018

- Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, ‘My Tsinghua Lament’, China Heritage, 3 April 2019

- The Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

***

I Reject the Blandishments of

This Era

我拒絕與這個時代和解

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Back then I was the same age as the students that I teach nowadays. Some of my classmates were a little older than me and had more real-world experience, and while we were all respectful of the gap determined both by age and propriety between ourselves and our teachers, nonetheless we enjoyed a definite camaraderie, more like a brotherhood, in fact. Someone would shout out ‘Meal Time!’ and we’d head out to the canteen laughing and chatting as we went. Since we all came from similarly impoverished circumstances none of us had any money to speak of. How innocent we all were; confident in our shared concern for the affairs of the nation and much of our time was devoted to heated debate and various heartfelt enthusiasms. We shared everything we had and treated each other like family — the star-speckled vault of the sky on those sweet nights of wafting breezes. It was akin to an idyll.

Such are the vivid memories of my youth, part of what these days they call ‘a story of the 1980s’; so close you feel you could touch it but also impossibly distant. Such memories remain intact even as everything else is being swept along in a tide of constant change, no matter how many classes, students or teachers come and go. In the blink of an eye, as if somehow caught unaware, I realise that I am as old as their parents.

And, suddenly, I also find myself to be somewhat out of joint with the times. Although I appreciate the inevitability of it, I’m ill-at-ease. ‘How to Be a Person’ [做人 zuò rén] — that famously demanding yet equally daunting expression, as old as old terms can be, and as common as any. Originally, it included the sense that ‘Knowing How to Behave Appropriately’ required the gradual sacrifice of one’s innate personality as one grew up: striding forward step by step while, as the Sage [Confucius] put it, gradually learning about the demands of the real world.

You may endure long enough to become an elder, but such a station in life doesn’t necessarily bring with it any great measure of respect, though given the generation gap at least you enjoy a perspective that affords you some understanding of the broader context of things. Young people are as delightful as ever, I suppose, just as we must have appeared to be to our own teachers, or just as our teachers were regarded by their teachers before them. But… but, vaguely, achingly, I feel compelled to make some observations about a particular kind of student whose numbers have proliferated of late, especially in our most prestigious educational institutions.

曾幾何時,年齡與學生相仿。有的同學齒德稍長,社會閱歷更多。在師生分際的有限禮儀之下,彼此實際分享的是兄弟情誼,張口喊飯,一笑出門。皆貧,身無分文;都天真,心懷天下。多少個時辰,議酣血熱,推杯換盞,稱兄道弟,風斜河漢天香夜,精神如畫。

它們構成了我青春記憶中的一抹彩色,說的是那一種叫做「八十年代」的故事,山遠水長。存在長存,萬物皆流,流水般的師生來來去去。一轉眼,不覺不曉,成了他們的父輩。

突然,有些不適應,悵然若失,欣慰而又張惶。「做人」,這個艱辛而莊敬的字眼,老話,大白話,原來意味著需要以畢生長旅為代價,一步一步往前跋涉,如夫子所言,始能徐徐知之也。

熬到父輩,未必收穫到了更多的尊敬,但因代際距離,卻有了遠遠審視的便利。他們還是那般可愛,一如我們曾經在自己的老師眼裡的模樣,也就如我們的老師在他們的老師心中的記憶。然而,隱隱的,痛痛地,覺得下面要說的這類學生漸漸多起來了,名校尤然。

What kind of students am I talking about? I’ll spare you the minutiae, instead I’ll offer you some general impressions.

The first thing you notice about them is that they are, without doubt, clever. Though the thing is they lack any real talent.

They are practiced at tackling exams successfully; they know precisely how to craft the kind of answers that will ensure them maximum scores, and they never miss a trick. But apart from being exam-ready they won’t deign to read any book that’s not a set text.

Here we can offer some details: what’s striking about campus life these days is that the high-achievers — the ‘Three Good Students’ [measuring up to the metrics and requirements of Party educators who judge them according to their ideological commitment, good study habits and carefully modulated behaviour within the school collective] hardly read a thing. That’s to say, basically they won’t read anything unless it contributes to better scores. And, they are carefully honed to be competitive; they’re all ready to participate in whatever competitions may yield a ‘Cup’ for this or an ‘Award’ for that. They are prepped and rehearsed for that down to a T. They know that all they really need to know is what is required to be known. As for the whys and wherefores of things, curiosity and interest: why bother with all of that stuff? After all, isn’t the goal to be accepted as a graduate scholar without actually having to take any qualifying exams? — Maybe, I guess, the only things that are intrinsically interesting to them are the useful; perhaps, too, only knowledge that can be deployed immediately has any abiding value.

What kind of diploma is required? Got it: I’ll take the tests for that. As to whether the student is interested in the particular subject or not, or if it even promises to catch their interest, well, that’s neither here nor there. Look for yourself: can you see them performing on stage? During the productions organised to celebrate [the founding of the Communist Party on] 1 July and 1 October [National Day] they sing the loudest. It goes without saying that everything about those voices conforms entirely with the mandated standards.

Growing up in a pedagogical environment that is obsessed with Exam Culture and Authoritarianism for over ten years such students are inculcated with the belief they must answer everything by the book; by so doing not only can they avoid being disoriented by the unknown, they are also assured of a pathway to Success. Paradoxically, the young people with sufficient inner fortitude to confront the unknown may very well wind up being eliminated by the system. — And us: their elders and people of their parents’ generation? What responsibility do we bear?

這是些什麼樣的學生呢?略去枝節,概莫如此這般。

首先,他們聰明,但無才華。

會考試,什麼樣的答案能得高分,就造出什麼樣的答案來,一點就通。答案之外,多讀無用,懶得溜一眼。

細數下來,高分學生,「三好生」,多半讀書甚少,好像也基本不讀與分數無關的書籍,蔚為學府新景象。會參賽,這個「杯」那個「杯」的賽事啦,培訓復加演練,按照要求做就是了,至於有理沒理,有趣無趣,何必想那麼多,不就是要一個免試入讀研究生的資格而已。——也許,有用就是有趣,有用等於有理。

需要什麼證書嗎?行呀,考一個,至於自己喜歡不喜歡,有意思沒意思,另當別論。瞧,「七一」、「十一」的歌台上,就數他與她的聲音嘹亮呢,那聲音可是完全符合標準的喲!

十多年的應試教育和威權主義生活氛圍早已教會他們,按照標準答案行事,不僅可以免去面對未知世界的迷茫,而且,一定引導向成功。執著於面對迷茫的,可能反而遭到淘汰。——我們這些父輩,該當何罪?

Secondly, they are boundlessly adaptable, even though they lack the spark of emotional engagement.

Don’t be fooled by their tender years: they are to a person practiced little diplomats and canny operators. It’s as though as soon as they had finished with childhood they leapt a stage and arrived at middle-aged maturity fully formed. They’ve simply deleted the precious stage of youth during which one’s mind is brimming with fantasies, ideas and imagination; that time of excitement and enthusiasm has simply been binned.

They have scoped out the lay of the land and they know full well that it’s to their advantage to seek out the patronage of ‘academo-crats with administrative clout’ — the men and women who can best facilitate their quest for ‘Success’, who will guide them with advice about the most profit-yielding courses or the kinds of activities that have a significant pay off . When they front up to Party and Youth League activities they have all the rote verbiage down pat; when it comes to extracurricular club activities they can veritably gush with enthusiasm; in their encounters with the professoriate their critiques are thoughtfully modulated; and, in the presence of the university’s Party Leaders, they display a self-confidence that is tempered by comely bashfulness. What a perfect combination: disarming guilelessness wedded to carefully calibrated worldly wisdom. But, putting all of that to one side: just what kind of people are these young men and women? Whatever counts as their inner reality silently, furtively skulks behind a façade of dazzling antics. You know the vapid but mannered expressions of those faces you see on the daily news? Many of them have the same kind of unctuous mien.

其次,他們應變,卻不見性情。

小小年紀,就人情練達,識時務,似乎從稚童一步進入成熟的中年,將那個充盈千萬種奇思妙想、熱血沸騰、叫做青春期的生命時段壓根兒刪去。

世事洞明,懂得結交「擔任行政職務」的教授,精於計算哪門課、哪件事有助於「成功」。黨團活動,講一口字正腔圓的;社團活動,來一段熱情洋溢的;碰上教授,或許發表點憤憤的;領導面前,即刻大方而嬌羞,單純無辜卻又知情達理。可他或者她究竟是個什麼樣的人呢?似乎永遠躲在多彩多姿卻又不動聲色的面龐之後。如今電視中天天出演新聞的那些面孔,不少就是這副德行。

So, given that the students I’m talking about here are utterly devoid of real ideals, what are their ambitions?

Their sole motivation is ‘Success’, pure and simple. Or, to cast it in more fashionable language, it is the ‘Pursuit of Excellence’. Let me be even more direct: it’s all about being ‘Bigger and Better’. Given the present state of affairs, for most people most of the time what this means involves two things: Power and Money, or whatever transient glittering objects are their equivalent. But, make no mistake, such ‘personal ambitions’ have absolutely nothing to do with meaningful social engagement, let alone a thought for the state and fate of the nation. Theirs is a bloodless pursuit.

When you read [the Chinese-American historian and 1930s’ Tsinghua graduate] Ping-ti Ho’s memoirs [讀史閱世六十年] all you really get is a series of accounts about his ‘studying overseas’, ‘competing for first place’ and similar folderol; it doesn’t compare to the intimate familiarity of Yang Chen-ning’s published recollections [六十八年心路; Yang was trained by a Tsinghua Professor at Southwestern University during the war]. It’s hard to feel any particular sympathy or engagement with Ho because his ambitions and ideals are so utterly divorced from each other. No matter how grand his stated ambitions may have been, spiritually his state of mind is that of pusillanimity. Although his academic achievement was undoubtedly out of the ordinary, as an individual he simply comes across as lacking in humanity.

再次,他們有志向,可理想貧乏。

志向就是「成功」,直截了當。或者,換一個表述,「卓越」。再直白而淺顯的,叫做「做大做強」。就當今之世的情形來看,多數時候其實不外權錢二字,以及其他可得藉此一般等價物置換的浮世物件。但是,個人志向無涉公共關懷,亦無家國之思,終究蒼白。

我們讀何秉棣先生的回憶錄,翻來覆去的不過就是「出國留學」、「爭當第一」這類嗚嗚呀呀,感覺上甚至不如讀楊振寧先生的回憶來得親切感人,難以生出同情來,原因就在於志向與理想的層階不同。其志固大,而精神境界渺矣!其業不凡,而人格氣象隳矣!

And, last of all, they very well might ‘dare to think and dare to act’; regardless, everything they do lacks conviction.

It’s all about me: that’s about as much as this lot of students can imagine; and they simply take whatever comes their way as simply being their due. It seems that repeated exam success has served only to exacerbate their befuddled sense of entitlement. I suppose that’s why they are so self-centred, so achingly selfish. It’s not a rapaciously possessive or gluttonous selfishness, rather it’s just an overweening self-regard, a vacuous arrogance that is willing to sacrifice any and all in a craven pursuit of Success. This is what exemplifies their character and dictates their behaviour. They know how to kick things off and get things done alright, but at no stage in the process, be it previously or in the future, does it involve any heartfelt enthusiasm.

Although China today is beset by problems it is equally confronted by a dearth of true political resolve, evidence of which is the tepid mediocrity we see that is limited to a pursuit of self-interest. The upshot of all of this is that no one wants to take responsibility; there’s a complete lack of selfless commitment. Long gone are the days when a magisterial great like Deng Xiaoping had the daring to transform the nation. It’s glaringly obvious what’s wrong with the education system of our Republic, now we are simply witnessing the ongoing effects of the disease.

最後,他們敢想敢幹,實際上並無血性。

萬物皆役於我,這是最敢想的,也是想當然的。似乎屢考屢中的少年得志,更加使得此一虛矯雲山霧罩。由此,自私,極度的自私,不是多吃多佔式的自私,而是惟我獨尊、為了成功不惜一切的虛矯,竟會成為他們的顯著人格特徵和行為方式。會動手,善執行;從來不曾、永遠不會熱血沸騰。

看看今日中國問題成堆,而獨缺政治決斷,表象為溫吞,囿於既得利益,實則不敢擔當,了無血性,早不復見鄧公當年之氣吞山河,便可見共和國教育有病,遷延發作罷了。

After they graduate and in, say, a dozen years or two decades from now they will be prominent figures, some will daresay even be outstanding or brilliant. At the moment, two particular terms occur to me that seem ready-made for them. In one particular environment, they are ‘The Successful’, a term I apply in a general sociological sense. In other circumstances, considering things from the perspective of political science, one can also already discern ‘The Technocrat’. Or let’s invoke a term favoured by Max Weber: ‘The Expert’.

Of course, they are but normal people; the problem is they are just too normal, so normal in fact that they cannot abide anything above the mediocre. They know all too well the specific requirements of these pragmatic times; they know exactly what their efforts are worth and how they should apply themselves. But perhaps they are too aware, too prematurely mindful. In their reverence for the Philosophy of Success they bend everything to their pursuit and everything they do revolves around it. And, indeed, for the most part, they will achieve the very Success of which they so ardently dream.

畢業後,約摸十幾、二十來年,他們就會出頭,一些人甚至光艷艷,亮燦燦。如今現成的兩個詞,好像是專為他們打造的。在一種場合,籠而統之社會學意義上的,叫「成功人士」;在另一些場合,直指要害政治學上的定位,稱為「技術官僚」,或者,馬克斯 . 韋伯的用語:「專家」。

他們是正常人,太正常了,連自己都容不得自己有一些兒出格。他們明白時代風氣的需要、自己的實用價值和努力方向,也太過明白了,太早就明白了。他們奉守成功哲學,孜孜於此,一切圍繞於此,也多半會走向夢寐以求的成功。

I think of the lament that Stefan Zweig expressed [in Die Welt von Gestern: Erinnerungen eines Europäers (1942)] when he recalled the poetry scene of 1930s’ Europe:

….when I think of those revered names that shone down on my youth, like constellations far beyond my reach, a sad question irresistibly comes into my mind: can there ever again be such pure poets, devoted only to lyrical form, in our present time of turbulence and general destruction?

For us, here and now in China, we also may well ask: what kind of age are we in, and what kind of new life is there here?

Zweig spoke about

a generation that has been deafened for years by the clattering millwheel of propaganda, and twice by the thunder of guns … our new way of life, which chases people out of their peace of mind like animals running from a forest fire.

Perhaps then this is the very kind of life that has now taken over Cathay, the Land of China, as well, this torrent has been unleashed and it is ever increasing in its intensity.

其實,當年茨威格環顧詩壇,就曾感喟,回想起曾如星漢照耀過自己青年時代的那些可親可敬的名字時,心中不禁疑惑:「在我們今天這樣的時代,在我們今天這樣一種新的生活方式之中,難道還會有那樣一群全心全意獻身於抒情詩藝的人嗎?」那麼,這是一種什麼樣的時代,又是一種什麼樣的新型生活方式呢?

茨威格說,在這個時代,常年充斥耳膜的不是宣傳機器的聒噪就是戰爭的隆隆炮聲;「這種新的生活方式扼殺了人的各種內在的專心致志,就像一場森林大火把動物驅趕出自己最隱蔽的窩一樣。」

可能,這一生活方式終於在神州登場了,而且,來勢凶猛,變本加厲。

Lost thus in contemplation and finding no solace in my indecisive cogitations, I go to seek out my own mentor. I talk to him about the trivial incidents of life, natter about the insignificant nothings that fill one’s days. The elder nods knowingly, shakes his head and nods some more. Suddenly he is overcome by a fit of coughing. After a while, as the episode passes, he turns to me slowly:

‘Does any of this really surprise you?’

That’s right, Gentle Reader: how could anybody think that any of the things I have been talking about here is out of the normal?

每念至此,無地徬徨,去找自己的老師,訴說流水帳,絮叨茶杯里的風波。老人家點頭又搖頭,搖頭復點頭,一陣忙亂,幾場咳嗽。末了,終於平靜下來,轉過頭來,緩緩道來:

「你覺著奇怪嗎?」

是呀,看官,你難道覺著有什麼奇怪的嗎!

Yet from my perspective as a person who is on the frontline of teaching I feel things simply aren’t right. Then again, is it possible that I haven’t changed sufficiently with the times and that I’ve ended up being like Old Mrs. Ninepounder [in Lu Xun’s story ‘Storm in a Teacup’ who repeatedly moans ‘Each generation is worse than the last.’ — trans. Gladys and Yang Xianyi]. As a teacher the most distressing thing about it all is that I feel alienated from my students. Or, rather, I feel as though I’m out of sync with the tenor of the times. So that’s why I must either go on as I have or I should retreat defeated and admit that I’m being too self-indulgent?

Or is my problem simply that [as the Song-dynasty poet Xin Qiji put it] ‘Agèd though I may be, still I feel unchanged from callow youth’?

可是,我這個教書匠,真的覺著有什麼事情不對勁兒了。莫非,時移世易,我已成了九斤老太?而身役教書匠,最為惆悵的,莫過於和自己的學生之間有了隔閡。或者,與這個當下時代風氣不和。於是,不進則退,自作多情?

又或,「老境何所似,只與少年同」?

***

Source:

- 許章潤, 我拒絕與這個時代和解, reprinted from the original dated 3 March 2018, and subsequently deleted from the mainland Chinese Internet

***