China Heritage Annual 2019

On 4 July 1945, Mao Zedong asked the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei (黃炎培, 1878-1965) what he had made of his visit to the wartime Communist base at Yan’an in Shaanxi province. Huang lauded the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters, but he had his doubts about whether the wartime frugality and solidarity could last. He predicted that the revolutionary ardour of the Communists could well wane if they ended up in control of China, and wondered out loud whether the endemic political limitations and blemishes of earlier Chinese regimes would return to haunt the new one, despite the best efforts of its committed idealists.

Would autocracy, cavalier political behaviour, nepotism and corruption once more come to rule over China? Huang said he could see no way out of the ‘vicious cycle’ of dynastic rise and collapse, though he certainly hoped that Mao and his followers would be able to break free of the wheel of history. Mao responded unequivocally:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone.

***

***

In 2018, seventy-three years after Mao met with Huang Yanpei in Yan’an, Xi Jinping was acclaimed the unquestionable leader of the People’s Republic of China; his role was hailed as 定於一尊 dìng yú yī zūn, ‘The Ultimate Arbiter’ — an ancient imperial epithet famously used to describe the unchallenged power of Ying Zheng (嬴政, 259-210 BCE), First Emperor of the Qin dynasty. Xi was also bestowed with the equivalent of lifetime tenure as chairman of the country’s party-state-army. Mao’s bold claim that the Communist Party would break the cycle of Chinese history was up for debate.

The Imperial Enterprise 帝業 dì yè

Ever since the collapse of the last dynasty in 1911, ‘Empire’ — or 帝業 dì yè, ‘the imperial enterprise’ in traditional terms — has been a source of anxiety for China’s political leaders, revolutionaries, thinkers, business people, journalists and citizens. Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary leader who became first president of the Republic of China, warned that even some of the revolutionaries around him regarded the restoration of dynastic rule and empire was inevitable (for more on this, see below). For his part, Mao Zedong — a man mocked in the republican government’s wartime capital of Chungking for expressing imperial ambitions — was obsessed with the possibility of a restoration, 復辟 fù bì, of the ‘semi-feudal and semi-capitalist’ past. After the Communist state of the People’s Republic of China, history, and how it was recounted according to Party dogma, was a central feature of national life. Since Mao’s death in 1976, Party leaders, thinkers and historians have recalled the Chairman’s 1945 exchange with Huang Yanpei, and they have been increasingly obsessed with the issue of 興衰 xīng shuāi, ‘the rise and decline [of rulership]’, an expression famously used by Sima Qian (司馬遷, 145-? BCE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty, in describing his understanding of political fortunes.

Internationally, the question of ‘the imperial enterprise’, 帝業 dì yè, is relevant to discussions about the nature of the Chinese polity, its internal constitution as well as its global ambitions. Therefore, a consideration of China, Empire and ‘Translatio Imperii’ — the transfer or transfiguration of rule or authority over time — in twenty-first-century China, may offer surprising insights into an old country dominated, for the most part, by a still-new people’s republic.

For this reason, we are making Translatio Imperii Sinici — the continuities of rule and empire in the Chinese world — the focus of the 2019 China Heritage Annual. The Latin expression ‘Translatio Imperii‘ generally refers to the centuries-long contest within Europe as to whether France or Britain were the true heirs to the succession of authority, the political grandeur, and the varied legacies, of Imperial Rome (Imperium Rōmānum, 27 BCE-284 CE), as well as all that denoted in regard to political imagination, governance, laws, philosophy, architecture and the arts. The Pax Britannica of the nineteenth century would be compared to the Pax Romana nearly two millennia earlier, just as, following World War II, the Pax Americana was hailed as ushering in a new global age that also trailed clouds of Roman glory.

Within the widely acknowledged Roman legacy lay another, equally contested, bounty, that of ancient Greece. The Roman empire was important to the rising British empire in a myriad of ways, but the early nineteenth century also witnessed a period of ‘Hellenomania’, an obsession that was sometimes framed in opposition to the perceived immobile autocracies of the Far East. As Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote in the Preface to his verse drama Hellas in 1821:

We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their root in Greece. But for Greece — Rome, the instructor, the conqueror, or the metropolis of our ancestors, would have spread no illumination with her arms, and we might still have been savages and idolaters; or, what is worse, might have arrived at such a stagnant and miserable state of social institution as China and Japan possess.

Shelley’s drama, the last work published in his lifetime, ends with a famous chorus, worth repeating here:

The world’s great age begins anew,

The golden years return,

The earth doth like a snake renew

Her winter weeds outworn:

Heaven smiles, and faiths and empires gleam,

Like wrecks of a dissolving dream….

Oh, cease! must hate and death return?

Cease! must men kill and die?

Cease! drain not to its dregs the urn

Of bitter prophecy.

The world is weary of the past,

Oh, might it die or rest at last!

In 2019, the world is experiencing a new age of autocracy and contested empire. It is an era in which, yet again, the world seems ‘weary of the past’, a time in which ‘hate and death return’. Well may we question whether ‘Heaven smiles, and faiths and empires gleam’.

Red Empires

From the 1917 Russian Revolution, the socialist camp would also lay claim to the legacy of imperial Rome and, in the 1930s, as Moscow was envisaged, and redesigned, as the centre of world revolution, Soviet architects were instructed to emulate some of the great Roman buildings, as well as the monumental Renaissance architecture that they had inspired throughout Europe. For example, Red Square, the focal point for displays of revolutionary ardour and military might, was designed in imitation of the Roman Forum; other Stalinist architectural gestures similarly recast venerable models from the imperial era. In turn, the grandiloquent design of Red Square would inspire the vast scale, and pomposity, of Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing, the capital of New China which, in the 1960s would vie to become worthy of the mantle of world revolutionary leader.

The topic of ‘Empire’ has enjoyed renewed debate among historians and political scientists for over a decade, and it has featured in our own work since the launch of China Heritage Quarterly in 2005 and through our advocacy of New Sinology 後漢學. It was a particular focus of my 2008 book The Forbidden City, as well as being prominent in the joint academic discussion of China’s Prosperous Age 盛世 from 2010, and in a collective undertaking to ‘Re-read Joseph Levenson’ over the years 2012 to 2014 (see The Practice of History and China Today, The China Story, 25 August 2015). My interest in the topic really began to take form in 1994, having been introduced to the work of Charles Moore in Los Angeles after my first trip to Las Vegas. My own account of ‘Learning from Las Vegas’ will be the topic of a future chapter in this Annual.

In Drop Your Pants!, our five-part series on the Communist Party’s 2018 patriotic education campaign, we discussed the creation in the 1920s of the Chinese party-state 黨國 dǎng guó, a Nationalist-era term revived in recent years to describe the People’s Republic. We also introduced the journalist Chu Anping’s observations on Party Empire 黨天下 dǎng tiānxià, a word he used to describe holistic Party control and one that re-entered China’s political vocabulary as a result of the investigative historian Dai Qing’s study of Chu, and China’s suppressed liberal political traditions, in 1989.

In light of developments during the first years of the Xi Jinping era (2012-), the political scientist Vivienne Shue has recently suggested the importance of discussing ‘the Sinic world’s singular experience of empire, imperial breakdown, and passage to political modernity’. Once more, it seems pressingly relevant to investigate the country’s 國體 guó tǐ — an ancient term revived for use in nineteenth-century Japan and subsequently ‘re-imported’ to China when thinkers were debating the nature of dynastic or, for that matter, post-dynastic government. 國體 guó tǐ is not merely about formal governance or the system of rule, or indeed limited to the ideological underpinnings of the state, it is also used to indicate ‘national essence’, that is those things which constitute a ruled territory, its mores and imagination, its identities and cultures, in fact, its total existential presence. In an essay titled ‘Party-state, nation, empire’, Shue asks: ‘What light … can reexamining China’s oddly intact transfiguration — from dynastic empire to people’s republic — shed on how the Party has governed since 1949?’ (See Shue, ‘Party-state, nation, empire: rethinking the grammar of Chinese Governance’, Journal of Chinese Governance, vol.3, August 2018: 268-291.)

In China Heritage Annual 2019 we will contribute to just such a line of inquiry, although our interests range beyond the immediate academic concerns of political scientists. While mindful of the yearnings, or at least nostalgia, for empire redux in such diverse modern polities as Erdoğan’s Turkey, Putin’s Russia, Modi’s India and Abe’s Japan, as well as however one manages to characterise the United States of America under Donald Trump, we would posit that Translatio Imperii, is no recent fad in China; indeed, it has been unfolding since the Taiping Civil War (1850-1864) and the Tongzhi Restoration (同治中興, 1860-1874, also known as the Self-strengthening Movement). It reached a significant contemporary moment in 1997 when Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin used the old Qing dynastic-era expression — ‘restoration’ 中興 zhōng xīng — to describe the post-1978 and post-1989 restoration of his regime’s fortunes. Our concerns, therefore, are not merely with the incipient ‘Red Empire’ of the Xi Jinping era — something discussed at length by Tsinghua Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 — but also with the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which still powerfully influence the Chinese world, and will continue to do so.

If we were to assay a Chinese translation of the Latin term Translatio Imperii, it would be 帝業之通變 dì yè zhī tōng biàn. This formulation combines the pre-Qin expression ‘the imperial enterprise’ 帝業 dì yè — the unified rule over a people and geopolitical territory, as well as the regulation of its customs, history and ideas, by a man of destiny and his successors, an ‘enterprise’ that reaches back well before the Common Era — with another hallowed term, 通變 tōng biàn, ‘the creative adaptation of familiar traditions’.

Forty Years in the Re-Making

To a certain extent, our consideration of Translatio Imperii Sinici and the re-making of empire in China has its origins in the years following Mao Zedong’s demise in 1976, even if it took decades to frame them in something approaching a coherent fashion. Inspired by Simon Leys’s observations in Chinese Shadows — quoted in the conclusion to this introduction — these cogitations took nascent form as a result of some sobering events in Beijing during the year 1979. For, even as the Communist Party was launching the country on a path to post-Mao economic transformation, the salvaging of Mao Zedong, and by extension of the People’s Republic of China itself, was well under way.

In 1979, voices of protests warned that Deng Xiaoping may well prove to be a new autocrat 獨栽者 dúcáizhě, and he soon proved the point by ordering the detention of the dissident Wei Jingsheng and quelling of public protest at Democracy Wall 西單民主牆. Advised by Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, Deng Liqun 鄧力群, as well as by their fellow Maoists-at-Heart, the Communist Party announced Four Basic Principles 四項基本原則 which were formulated to rationalise and strengthen the one-party state. Those developments, and the subsequent ideological, cultural and political purges of the 1980s, prepared, both by design and as a result of happenstance, the way for the rise today of another autocrat with global ambitions. What may now seem to have been the inevitable rise of a latter-day ‘Chinese Napoleon’ (or a new-age Qianlong, as some have suggested) was, at that time at least, already clearly evident in terms of 勢 shì — potential, propensity and possibility.

The particular confluence of ideas, events, personalities and history that has contributed to our focus on Translatio Imperii Sinici, including a discussion of 勢 shì, will feature in future chapters in China Heritage Annual 2019. For the moment, let’s return to wartime Yan’an.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 January 2018

- For the background of China Heritage Annual, see the Editor’s Note at the end of this essay. My thanks to Annie Ren 任路曼 and Callum Smith for their assistance.

Rebels in the Wilderness

The delegation that visited Yan’an in July 1945 also included Fu Sinian (傅斯年, 1896-1950), a respected May Fourth-era activist and a leading historian who, among other things, had been writing A Revolutionary History of the Chinese Nation.

Fu was a student leader during the 4 May 1919 demonstrations, and was already an established cultural figure when he encountered Mao, a lowly library assistant at Peking University. The Communist leader recalled with chagrin that famous men like Fu had no time for a country bumpkin like himself. When they met again in Yan’an in 1945, however, Mao did not mention his long-harboured grievance. Instead, during the course of a private conversation, also on 4 July, Mao praised Fu for his intellectual contributions to the anti-feudal push of the May Fourth era, which itself helped engender the creation of the Communist Party. With suitable modesty Fu responded that his generation of agitators were like the upstarts Chen Sheng 陳勝 and Wu Guang 吳廣 who had rebelled against the tyranny of the Qin dynasty (second century BCE); it was Mao and his colleagues who were the real heroes, like Liu Bang 劉邦 and Xiang Yu 項羽. After all, Liu Bang went on to become the founding emperor of the Han, one of the greatest dynasties in Chinese history. It was a tactful response, one that flattered the Communist leader while preserving Fu’s own sense of dignity. It was an exchange also well suited to Yan’an, which was in the heartland of the area that formed the core of the Qin empire over two millennia earlier.

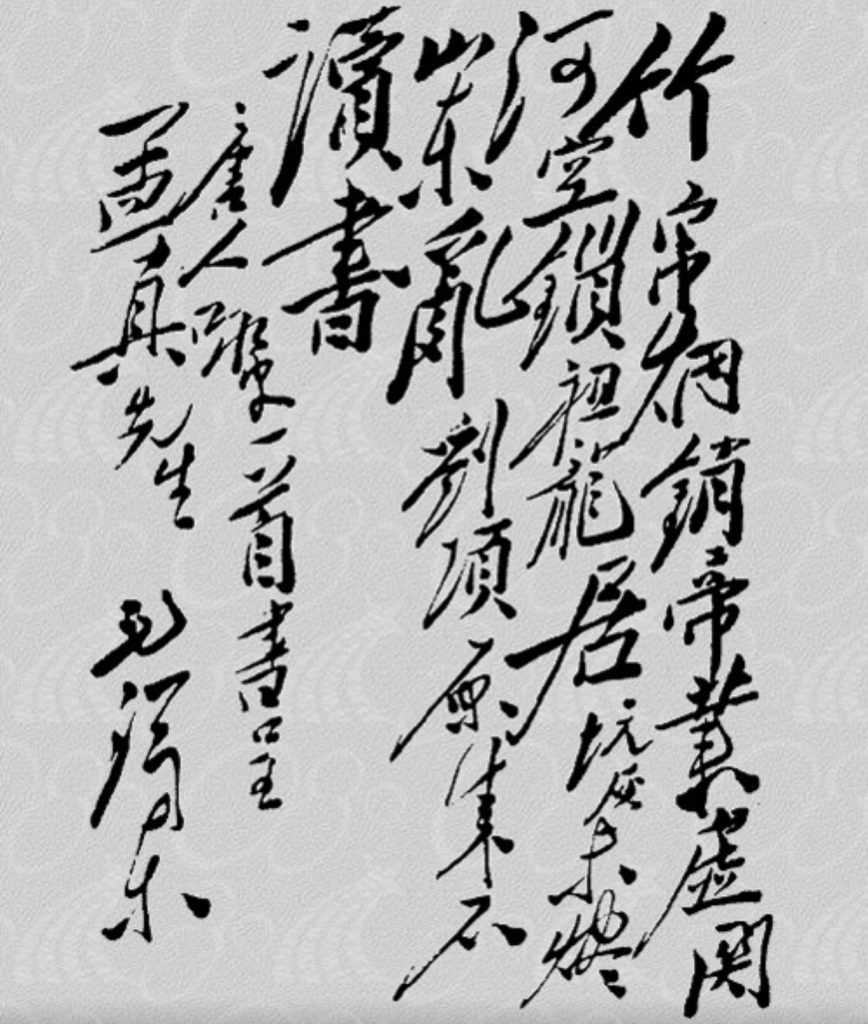

As was common practice among men of letters at the time, Fu asked Mao for a piece of calligraphy as a memento of their encounter. The following day he received a hand-written copy of ‘The Pit of Burned Books’ 焚書坑 by the late-Tang poet Zhang Jie (章碣, eighth century CE). In the accompanying note Mao remarked, ‘I fear you were being too self-effacing when you spoke of Chen Sheng and Wu Guang…. I’ve copied out a poem by a Tang writer to expand [on our discussion]’.

The poem spoke of the vain attempt by the First Emperor of the Qin to quell opposition to his draconian rule by burning books and burying scholars.

In full the poem reads (in my translation):

All those words gone up in smoke

The Imperial Enterprise but a ruin

Hard-won lands and passes lie useless

The Dragon lineage trapped in its lair.

The ashes in the pit not yet cold,

Rebellion came from the east,

Liu Bang and Xiang Yu

Had no use for letters.

竹帛煙銷帝業虛,

關河空鎖祖龍居。

坑灰未冷[燼]山東亂,

劉項原來不讀書。

Offering Fu this poem was a caustic way for Mao to chide a man who had been at the intellectual forefront for many years. In effect, he was saying that Fu Sinian’s rebellion against the feudal traditions of China was vainglorious, more so even than the failed uprising of the peasant rebels Chen Sheng and Wu Guang against the Qin. Besides, real heroes like Liu Bang and Xiang Yu were men of action and cared not for book learning — to Mao the fatal flaw of so many May Fourth era intellectual activists, despite his own bookish obsessions.

Mao’s false modesty in claiming that he and his cohort were, like Liu and Xiang, unlettered rebels, also betrayed a confidence that he would lead the Communist army to victory over the existing political order. It was a theme to which he would return many times. And, under Mao, the First Emperor of the Qin would become a positive symbol of unity, political acumen and uncompromising principles. Despite the odium associated both with him, and Mao, the First Emperor still has a unique position in the Communist pantheon of progressive feudal rulers, a subject we will discuss elsewhere.

In the exchange with Fu Sinian, coupled with the publication of Mao’s famous poem ‘Snow’ 雪 later that same year, we see evidence of both the hauteur of the Communist leader and his ambivalence in regard to traditional rulership (for more on this, see For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone, China Heritage, 27 January 2018). He evokes that tradition both through historical reference and in actual practice. By placing his cause, and that of the Chinese people, in the context of dynastic-era peasant uprisings, Mao Zedong expressly, and repeatedly, identified with a history of rebellion. He declared that this latest uprising, led by a proletarian vanguard and directed by visionary revolutionary leaders with a modern anti-feudal political philosophy, would break the dynastic cycle forever (the persistent dangers of the ‘cyclical law’ of autocracy were famously discussed by the educationalist Huang Yanpei during his own meeting with Mao in Yan’an) and found a new government that would outshine in achievement all the greatness of the past. It was this same ambivalence — a claim both for legitimacy in traditional terms and a self-identification with the role of rebel outsider at war with the past — that would be evident a few years later when the Communist forces marched on the old imperial capital of Beiping (Beijing).

Peasants in the Palace

Regardless of arguments about how ‘new’ the New China may or may not be or, more recently, that Xi Jinping’s vaunted New Epoch 新時期 lays claim to being some unique historical moment, the Chinese party-state has from 1949 frequently manipulated imperial metaphors as part of its seventy-year-long effort to Make China Great Again under its aegis. This has been particularly evident from the 1990s. Since then, the Party has made an uncomfortable peace with the Manchu-Qing dynasty (1644-1912), the rulership of which was long excoriated as being responsible for China’s ‘century of humiliation’. With the disavowal of revolution in favour of rulership, the Communists have in numerous ways asserted their right not only to lead China in new directions, but also to be regarded in the lineage of legitimate political succession 正統 zhèng tǒng, rightfully to maintain a stranglehold on the holistic unity of power, thought, society and culture 大一統 dà yī tǒng and represent cultural orthodoxy 道統 dào tǒng, the history of which is ascribed as dating back to the first empire, the Qin dynasty, in the second century BCE. To that end, formidable party-empire-state-building enterprises, including, from 1992, major projects to rework Chinese history and every aspect of culture and heritage according to the Party’s vision of and for China, have been launched and funded generously.

‘Empire redux’ has been an even more notable feature of the Chinese propaganda landscape in the new millennium, especially as the local geopolitics of the capital Beijing were reoriented, and the mid-Qianlong reign of the eighteenth century was used to re-imagine an idealised city (topics that will be addressed in future chapters of Translatio Imperii Sinici). Then there was the initiation of a well-funded project to write a new, authoritative history of the Qing dynasty itself; this was both an impressive historiographical undertaking as well as amounting to a symbolic recognition that the People’s Republic of China now regarded itself as the rightful successor regime to the once-excoriated ‘Manchu-Qing’. (For more on this, see the 2011 issue of China Heritage Quarterly devoted to China’s Prosperous Age 盛世.) The Qing History Project also provides an important historical context, and political pretext, for the Communist Party’s policies both in Tibet and Xinjiang (see, for example, Zhou Qun 周群, ‘Firmly Maintain the Discursive Control of Qing History Research’ 牢牢把握清史研究話語權, 人民日報, 14 January 2019). Party-state control over history was further enhanced when, on 3 January 2019, Xi Jinping congratulated the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences on the establishment a new research institute devoted to the Party-approved study of Chinese history. China’s historians, Xi wrote:

must adhere to Historical Materialism and apply its ideas and methodologies while grounding themselves in China, contemplating the world as a whole, standing at the crest of the wave and understand change, both past and present, and be a prescient voice. 堅持歷史唯物主義立場、觀點、方法,立足中國、放眼世界,立時代之潮頭,通古今之變化,發思想之先聲。

As I noted in the introduction to my 2008 book, The Forbidden City, however:

Thirty-five years after the fall of the Qing dynasty, at the time of the creation of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong and his comrades … chose to locate their Communist government in the former imperial enclave of the Lake Palaces [Zhongnan Hai 中南海]. This only reinforced the impression, however, that, while rulers may come and go, the system as well as the habits of Chinese autocracy stay the same. As Franz Kafka put it, ‘the empire is immortal’. As much as Mao and his fellow revolutionaries might rail against the habits of the feudal past, their language, literary references and political infighting were carried out in its shadow. The palace, a metaphor for Old China, persisted as a metaphor for New China. …

Throughout their rule, Mao and his supporters would use the symbols and language of the dynastic past and convert them into elements of their own political performances and vocabulary. They employed tradition when it suited them and repudiated it when the need arose. … The Forbidden City and the China that it represented … retained a power that was not so easily dispelled. While its buildings were subject to decay and change, the China of secretive politics, rigid political codes and autocratic behaviour continued to exert an influence far beyond the walls of the former palace.

— Geremie R. Barmé, The Forbidden City,

Harvard University Press, 2008, pp.xiv-xv & 2

***

The Struggle for the Throne

In China, the majority of individuals endowed with a powerful ambition have from antiquity onwards dreamed of becoming emperor … . This kind of ambitious person has always existed in all periods of history. When I began to advocate revolution, six or seven out of ten of those who rallied around were harbouring this type of imperial dream at the outset. But our aim in spreading the revolutionary ideal was not only to overthrow the Manchu dynasty, it was in fact to set up the republic. We therefore gradually succeeded in ridding the majority of these individuals of their imperial ambitions. Nevertheless, there remained among them one or two who, as much as thirteen years after the founding of the republic, had not yet abandoned their old ambition of becoming emperor, and it was for this very reason that even in the ranks of the revolutionary party people were continually cutting each other’s throats … . If everyone retains this imperial mentality, a situation arises where comrades fight each other, and the whole population of the country is divided against itself. When these unceasing fratricidal struggles spread throughout the country, the population is overwhelmed by endless calamities … . Thus in the history of China through the generations, the imperial throne has always been fought over, and all the periods of anarchy which the country has then gone through have had their origin in this struggle for the throne. … In China there has for the last few thousand years been a continual struggle around the single issue of who is become emperor!

中國自古以來,有大志向的人,多是想做皇帝 … 此等野心家代代不絕。當我提倡革命之初,來贊成革命的人,十人之中,差不多有六七人,是一種帝王思想的。但是我們宣傳革命主義,不但是要推翻滿清,並且要建設共和,所以十分之六七的人,都逐漸被我們把帝王思想化除,但是其中還有一二人,就是到了民國十三年,那種做皇帝的舊思想,還沒有化除,所以跟我來做革命黨的人,常有自相殘殺的,就是這個原故。… 大家若是有了想做皇帝的心理,一來同志就要打同志,二來本國人更要打本國人。全國長年相爭相打,人民的禍害,便沒有止境。… 中國歷史常是一治一亂,當亂的時候,總是爭皇帝。… 中國幾千年以來,所戰爭的都是皇帝一個問題。

— Sun Yat-sen, ‘First Lecture on Principles of Democracy’, 9 March 1924

孫中山, 三民主義, 民權主義第一講, 1924年3月9日

translated from the French of Simon Leys (1971) by

Carol Appleyard and Patrick Goode in

The Chairman’s New Clothes (1977)

Shadows of the Past

We conclude this introduction to China Heritage Annual 2019 with a passage from Chinese Shadows, Simon Leys’s famous impressionistic work about late-Maoist China. It is a book that detected the long shadows that continue to darken the rule of Mao’s successors:

If the destruction of the entire legacy of China’s traditional culture was the price to pay to insure the success of the revolution, I would forgive all the iconoclasms, I would support them with enthusiasm! What makes the Maoist vandalism so odious and so pathetic is not that it is irreparably mutilating an ancient civilization but rather that by doing so it gives itself an alibi for not grappling with the true revolutionary tasks. The extent of their depredations gives Maoists the cheap illusion that they have done a great deal; they persuade themselves that they can rid themselves of the past by attacking its material manifestations; but in fact they remain its slaves, bound the more tightly because they refuse to realize the effect of the old traditions within their revolution. The destruction of the gates of Peking is, properly speaking, a sacrilege; and what makes it dramatic is not that the authorities had them pulled down but that they remain unable to understand why they pulled them down. …

A countersuperstition is not less a superstition: under the old regime town walls were venerated; under the new one they are under attack. The fury of the iconoclasts is a negative measurement of the permanence of the sacred powers that ruled feudal society. The tragedy is that the sacred powers dwell not in those innocent stones, whose beauty is sacrificed in vain, but in the minds of the wreckers. Seen in this light, the Maoist enterprise appears hopeless; the regime may well change China into a cultural desert without succeeding in exorcising the ghosts of the past: these ghosts will continue their paralyzing tyranny so long as the regime is unable to identify them within itself. But will it ever be capable of such clear vision? Certain foreign Sinologists, guilty of having noted traces of the traditional way of thinking in the Maoist systems, are the focus in Peking of surprising hatred out of all proportion to their limited audience or influence.

This shows, I’m afraid, how little the Maoist authorities are ready to re-examine critically the old cliches in which they have locked the concepts of ‘old’ and ‘new’, ‘feudalism’ and ‘progress’, ‘reaction’ and ‘revolution’. By refusing to examine the nature and identity of its revolution in depth, the People’s Republic condemns itself to marking time, to struggling in the dark, producing such periodic sterile explosions as the Cultural Revolution. It can have little hope of liberating itself from the slavery of the past as long as it hunts it among old stones, instead of denouncing its active reincarnation in the ideology and political practices of the new mandarins.

— Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows (Ombres Chinoises, 1974)

New York: The Viking Press, 1977, pp.58-60

***

Editor’s Note: About China Heritage Annual

China Heritage Annual is a series produced by China Heritage, the online home of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology 白水書院. Along with the China Heritage Journal it is a successor to China Heritage Quarterly, an e-publication produced under the aegis of the China Heritage Project from 2005 to 2012.

China Heritage Annual also pursues some of the issues developed by The China Story Project, founded in 2012. For its part, the Project continues to produce China Story Yearbook:

- Red Rising, Red Eclipse, 2012

- Civlising China 文明中華, 2013

- Shared Destiny 共同命運, 2014

- Pollution 染, 2015

- Control 治, 2016

- Prosperity 富, 2017

Over the years, China Heritage Quarterly published issues focussed on a number of cities, their history, politics and culture: Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Hangzhou/ West Lake. The inaugural issue of China Heritage Annual, published during 2017, was devoted to the city of Nanking. New material is still being added to the inaugural volume, as it is to the 2018 issue on the theme of Watching China Watching.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor

China Heritage Annual