The Other China

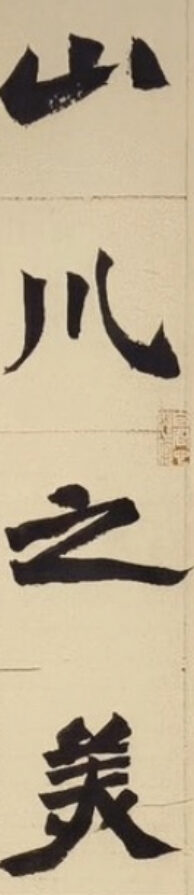

山川之美

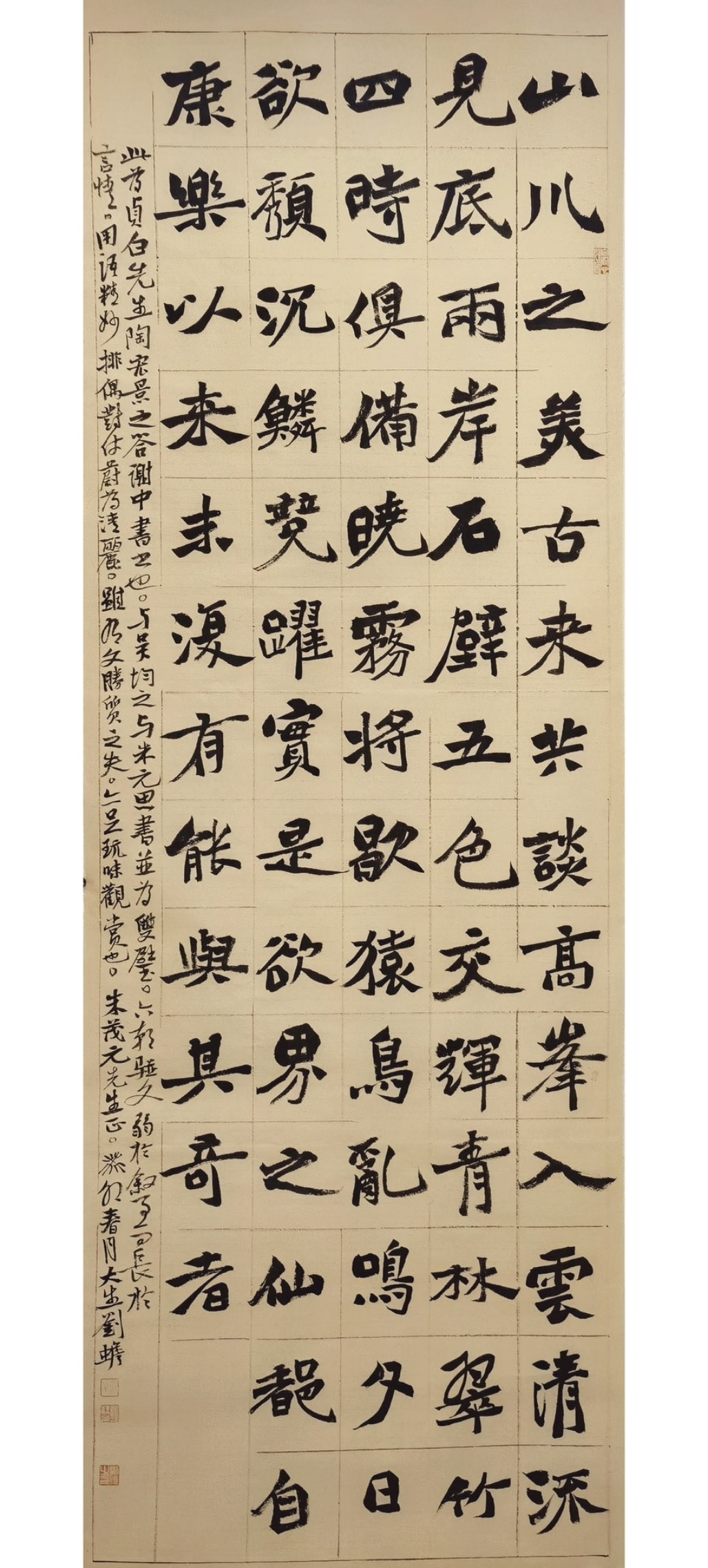

This addition to our series The Other China was inspired by a calligraphic work by Liu Chan 劉蟾, artist, editor and educator, written for a friend by the name of Zhu Maoyuan 朱茂元.

On 22 February 2023, Liu published his calligraphic interpretation of ‘Letter in Reply to Secretary Xie’ 答謝中書書, a famous work by the polymath Tao Hongjing (陶弘景, 456-536 CE). In A Gallery of Chinese Immortals: Selected Biographies Translated from Chinese Sources (1948), the Sinologist and translator Lionel Giles remarked that Tao’s ‘versatility was amazing: scholar, philosopher, calligraphist, musician, alchemist, pharmacologist, astronomer, he may be regarded as the Chinese counterpart of Leonardo da Vinci.’

In the colophon to this copy of Tao Jinghong’s letter, Liu Chan notes that this short encomium on landscape is often paired with a ‘Letter to Zhu Yuansi’ 與朱元思書 by Wu Jun (吳均, 469-520 CE), who was Tao’s contemporary.

Both works were written during the Northern and Southern dynasties, a time of extraordinary political turmoil as well as of cultural efflorescence. It was also an era during which, in some regards, ‘the landscape’ became the supreme subject of Chinese literature and art.

As a cultural theme in the Chinese world the landscape is often referred to as 山水 shānshuǐ, ‘Mountains and Rivers’, or 山川 shān chuān, ‘Mountains and Streams’. The expression 江山 jiāng shān — ‘Rivers and Mountains’ — however, generally denotes a geopolitical landscape, ‘the realm’, or a territory dominated by an autocratic political regime. Xi Jinping, China’s latest autocrat, is obsessed with the expression (see, for example, Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, 8 August 2018) and, because of patriotic fervor in the People’s Republic over Taiwan — the place where a decent Chinese government has ‘sought peace to one side’ 偏安一隅 — the term 河山 hé shān, famous due to its association with the Song general Yue Fei 岳飛, has gained renewed currency (see Commemorating a Different Centenary, 12 October 2021).

By contrast, Tao Jinghong’s essay is a lyrical celebration of ‘the beauty of mountains and streams’ 山川之美 shān chuān zhī měi. Tao ends his letter on the landscape — ‘the true Paradise of the Region of Earthly Desires’ 實是欲界之仙都 — on a plaintive note when he says that:

… since the time of Xie Lingyun, no one has been able to feel at one with these wonders, as he did.

自康樂以來,未復有能與其奇者。

However, this provides an excuse to reproduce a number of poems by Xie Lingyun (謝靈運, 385-433 CE), or Xie Kangle 謝康樂, one of China’s greatest landscape poets (for biographical details, see John Frodsham’s note below).

The following translations by John Frodsham (1930-2016), both of Tao Hongjing and of Xie Lingyun, are taken from Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), edited by John Minford and Joseph M. Lau. This work, and the companion volume of Chinese sources, is essential reading for those who would venture into the Memory Palace of Chinese literature, as well as anyone who is interested in New Sinology and The Other China. As I have observed,

when things with China ‘went south’ — that is as the systemic inertia of party-state autocracy continued to cast a pall over contemporary Chinese life, as I had no doubt that it would following the events of 1989 — students and scholars would always have recourse to the vast world of literature, history and thought that make a study of China also a study of human greatness, genius and potential.

— from New Sinology in 1964 and 2022, 26 December 2022

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

24 February 2023

***

Related Material:

- Readings in New Sinology

- Conflicting Loyalties

- 1949-2009: Sixty Years Out of Range

- Liu Chan’s Memorial for the Departed

- Lois Conner’s China Landscapes

- On Heritage 遺

- Six Dynasties 魏晉南北朝, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking

Mornings, I wait for the rush of the evening breeze,

Evenings, I watch for the morning sun to rise.

Light cannot linger under these beetling crags,

In the forest depths the slightest sound carries far.

When sadness has gone then thought can return again,

Once wisdom has come, passion no longer exists.

Would that I were the charioteer of the sun!

Only this would bring some solace to my soul.

Not for the common herd do I say these things,

I should like to talk them over with the wise.早聞夕飆急,晚見朝日暾。

崖傾光難留,林深響易奔。

感往慮有復,理來情無存。

庶持乘日車,得以慰營魂。

匪為眾人說,冀與智者論。

— Xie Lingyun, trans. John Frodsham

Letter in Reply to Secretary Xie

答謝中書書

Tao Hongjing 陶弘景

in the hand of Liu Chan 劉蟾

translated by John Frodsham

***

Men have always spoken and will always speak of the beauty of mountains and streams. High peaks that go soaring into the clouds; translucent torrents, clear to their very bottoms, flanked on either side by cliffs of stone, whose fivefold colors glitter in the sun; green forests and bamboos of kingfisher-blue, verdant through every season of the year. As the mists of dawn roll aside, the birds and monkeys cry discordantly. As the evening sun sinks to rest, the fishes vie at leaping from their deep pools. Here is the true Paradise of the Region of Earthly Desires. Yet, since the time of Xie Lingyun, no one has been able to feel at one with these wonders, as he did.

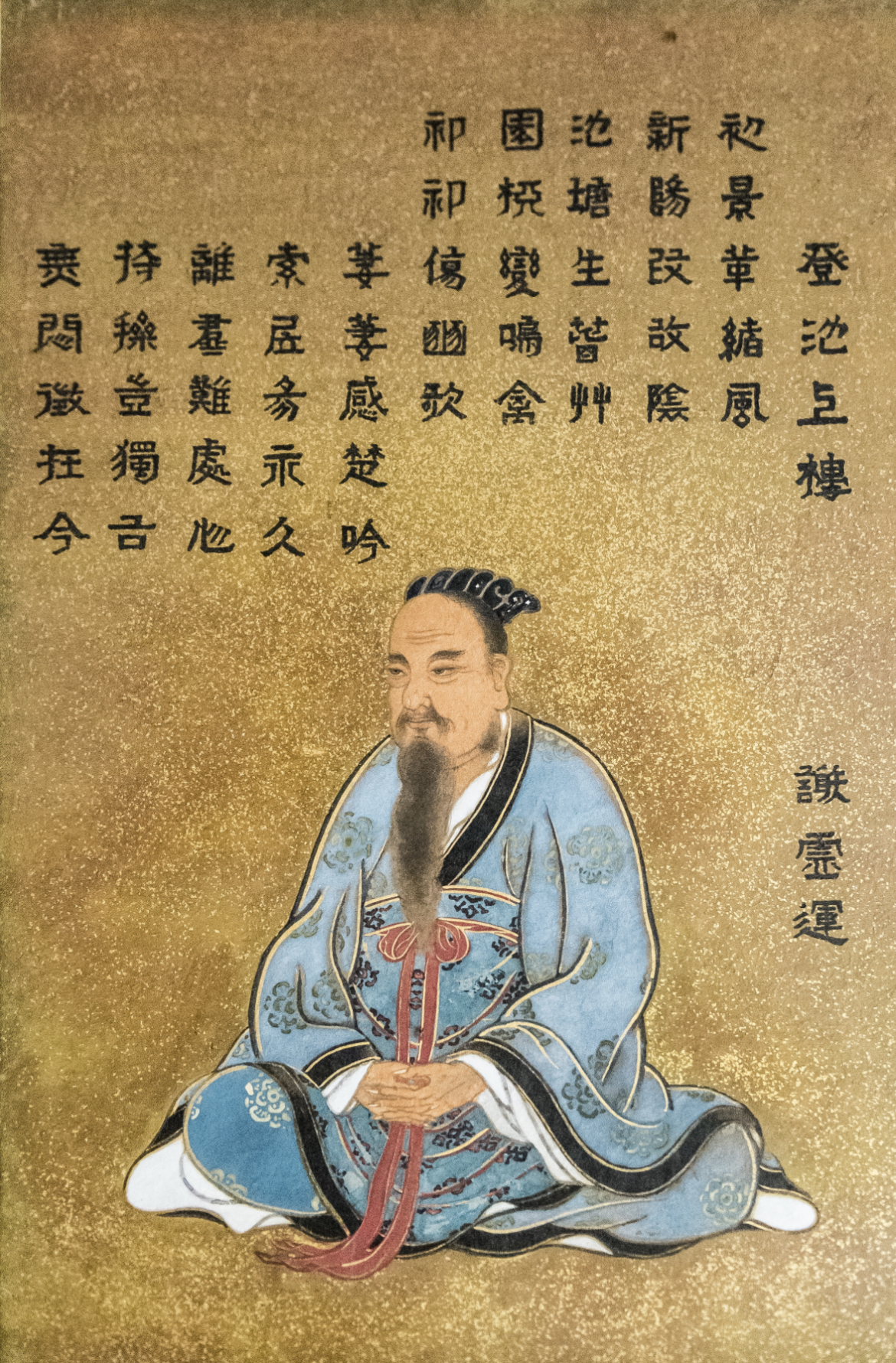

Xie Lingyun

謝靈運, 385-433 CE

John Frodsham

Xie Lingyun, Duke of Kangle, was born into one of the most illustrious families of the Six Dynasties. His great grand-uncle Xie An (320-385) had been Prime Minister, his grandfather, Xie Xuan (943-385), had thrown back Fu Jian’s invading army at the battle of the Fei River in 383, and so prevented the northern “barbarians” from seizing the south. Given such advantages, Lingyun would have seemed assured of a brilliant career at court; yet this persistently eluded him. When the Jin collapsed in 419, he joined forces with the Liu Song dynasty. But in 422 his enemies, jealous of his friendship with the heir to the throne, the Prince of Luling, exiled him to Yongjia (Wenzhou in Zhejiang province) and murdered the prince. It is from this period that his finest verse must be dated: suffering had made a poet out of a competent versifier. For the next ten years he alternated between intervals of seclusion on his estate and spells of discontented service as an official. Finally, he ran foul of a powerful clique at court, was exiled to Guangzhou, and executed there on a trumped-up charge.

Brought up as a Taoist in the esoteric sect of the Way of the Heavenly Master, Lingyun soon became a fervent convert to Buddhism. He joined the community on Mount Lu, under the famous Huiyuan (334-416), and distinguished himself by his essays on Buddhist philosophy and his translation of several sutras. But his real contribution to Chinese literature lies in his nature poetry, which grew out of his love for the picturesque mountains of Zhejiang and Jiangxi. He liked wandering among the hills, and even devised a special pair of mountaineering boots, with removable studs, to enable him to scale the most difficult peaks. As a nature-poet he is unsurpassed; his verse resounds with the roar of mountain torrents, is redolent of the scent of wind-tossed pines. … [He] is undoubtedly one of the finest poets of the whole period, the inspiration of many later writers, Li Bo and Du Fu among them. Brilliant, sensitive, and eccentric, his verse gives us the measure of the man.

— Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, p.524

***

***

On Climbing the Highest Peak of Stone Gate

At dawn with staff in hand I climbed the crags,

At dusk I made my camp among the mountains.

Only a few peaks rise as high as this house,

Facing the crags, it overlooks winding streams.

In front of its gates a vast forest stretches,

While boulders are heaped round its very steps.

Hemmed in by mountains, there seems no way out,

The track gets lost among the thick bamboos.

My visitors can never find their way,

And when they leave, forget the path they took.

The raging torrents rush on through the dusk,

The monkeys clamour shrilly through the night.

Deep in meditation, how can I part from Truth?

I cherish the Way and never will swerve from it.

My heart is one with the trees of late autumn,

My eyes delight in the buds of early spring.

I dwell with my constant companions and wait for my end,

Content to find peace through accepting the flux of things.

I only regret that there is no kindred soul,

To climb with me this ladder to the clouds in the blue.登石門最高頂詩

晨策尋絕壁,夕息在山棲。

疏峰抗高館,對嶺臨迴溪。

長林羅户穴,積石擁階基。

連嚴覺路塞,密价使徑迷。

來人忘新術,去子惑故蹊。

活活夕流駛,噭噭夜猿啼。

沈冥豈別理,守道自不攜。

心契九秋榦,目翫三春荑。

居常以待終,處順故安排。

惜無同懷容,共登青雲梯。

***

What I Saw When I Had Crossed the Lake on My Way from South

Mountain to North Mountain

The poet, on his way across the lakes, stops at the mountainous island separating them, and enjoys the view.

In the morning I set out from the sun-lit shore,

When the sun was setting I rested by the shadowy peaks.

Leaving my boat I gazed at the far-off banks,

Halting my staff, I leant against a flourishing pine.

The narrow path is dark and secluded,

Yet the ring-like island is bright as jade.

Below I see the tops of towering trees,

Above I hear the meeting of wild torrents.

Over the rocks in its path the water divides and flows on,

In the depth of the forest the paths are free from footprints.

What is the result of “Delivering” and “Forming”Everywhere is thick with things pushing upward and growing.

The first bamboos enfold their emerald shoots,

The newborn rushes hold their purple flowers.

Seagulls play on the vernal shores,

The heaven-cock flies up on the gentle wind.

My heart never tires of meeting these Transformations,

The more I look on Nature, the more I love her.

I do not regret the departed are so remote,

I am only sorry I have no one as a companion.

I wander alone, sighing, but not from mere feeling;

Unsavored nature yields to none her meaning.

於南山往北山經湖中膽眺詩

朝旦發陽崖,景落憩陰峰。

舍舟眺迴渚,停策倚茂松。

側逕既窈窕,環洲亦玲瓏。

俛視喬木杪,仰聆大壑淙。

石橫水分流,林密蹊絕蹤。

解作竟何感,升長皆豐容。

初篁苞綠籜,新蒲含紫茸。

海鷗戲春岸,天雞弄和風。

撫化心無厭,覽物眷彌重。

不惜去人遠,但恨莫與同。

孤遊非情歎,賞廢理誰通。

***

I Follow the Jinzhu Torrent, Cross the Peak, and Go Along by the River

When the monkeys howl, I know that dawn has broken,

Though yet no sun has touched this shadowed valley.

Around the peaks the clouds begin to gather,

While dew still glistens brightly on the flowers.

My path winds round beside a curving river,

Then climbs far up among the rock-bound crags.

With gown held high, I wade the mountain torrent,

Then toil up wooden bridges, ever higher.

Below, the river islets wind around,

But I enjoy following the sinuous stream.

Duckweed floats upon its turbid deeps,

Reeds and cattails cover its clear shallows.

I stand on a rock to fill my cup from a cataract,

I pull down branches and pluck their leafy scrolls.

In my mind’s eye I see someone in the fold of the hill,

In a fig-leaf coat and girdle of rabbit-floss.

With a handful of orchids I grieve for my lost friendship

I pluck the hemp, yet can tell no one how I feel.

The sensitive heart will find beauty everywhere —

But with whom can I discuss such subtleties now?

從斤竹澗越嶺溪行詩

猿鳴誠知曙,谷幽光未顯。

最下雲方合,花上露猶泫。

透迤傍隈隩,迢遞陟陘峴。

過濶既厲急,登棧亦陵緬。

川渚屡徑復,乘流翫迴轉。

蘋萍泛沈深,菰蒲冒清淡。

企石挹飛泉,攀林摘葉卷。

想見山阿人,薜蘿若在眼。

握蘭勤徒結,折麻心莫展。

情用賞為美,事昧竟誰辨。

觀此遺物慮,一悟得所遣。

***

Last Poem

The allusions in the first four lines of this poem provide analogies with Xie’s own case. Gong Sheng (68 B.C.-A.D. 11) starved himself to death rather than serve the usurper Wang Mang; Li Ye (first century A.D.) also preferred death to serving the usurper Gongsun Shu, who, incensed at his refusal, had him poisoned; Xi Kang … had been unjustly put to death on the flimsiest of evidence; and Huo Yuan was executed by the would-be usurper Wang Jun (252-314).

Lingyun wrote this last poem on the eve of his execution. On his way to the execution, so the story goes, he cut off his splendid goatee and presented it to the Jetavana monastery in Nanhai to serve as a beard for an image of Vimalakirti. He died as he had lived — philosophical, eccentric, courageous — a poet and an aristocrat to the last. His body was brought back to Kuaiji and laid to rest there among the mountains he loved so well.

— The Editors of Classical Chinese Literature

Gong Sheng had no life left to him,

Li Ye came to an end.

Xi Kang was harassed for his truth,

Master Huo too lost his life.

Thick and green the cypress, heedless of the frost,

Soaked with dew the mushroom, suffering in the wind.

What does a happy life amount to after all?

I am not troubled by its brevity.

I only regret that my resolution as a gentleman

Could not have brought me to my end among the mountains.

To deliver up my heart before I achieved Enlightenment

This pain has been with me for long.

I only pray I may be born again

Where friend and foe alike might share

The same desires.

臨終詩

龔勝無餘生,李業有終盡。

嵇公理既迫,霍生命亦殞。

悽悽後霜柏,納納衝風菌。

邂逅竟幾時,修短非所愍。

恨我君子志,不獲嚴下泯。

送心正覺前,斯痛久己忍。

唯顧乘來生,怨親同心朕。