Hong Kong Apostasy

In this chapter of ‘The Best China’, two prominent commentators — Lee Yee 李怡 and To Kit (陶傑, Chip Tsao, 1958-) — discuss the pathology of the power-holders in Hong Kong and Beijing. Lee and Tsao focus their attention on particular aspects of the ‘Chinese National Character’, itself a topic that has been the centre of political and social debate in the Chinese world for well over a century.

The Sick Man of Asia

In the late-nineteenth century two declining empires shared a reputation for being economically decrepit, politically backward and socially effete. One, the Ottoman Empire in Asia Minor was dubbed ‘The Sick Man of Europe’. Some decades later, critics of the Manchu-Qing empire to the far east called it ‘The Sick Man of East Asia’ 東亞病夫. At the time, paramount among the concerns of the expansionist Western trading powers, as well as of a revitalised Empire of Japan in the case of China, was that makeshift remedies be sought so that, despite their political desuetude, the supine giants could still serve a role in the contestation between the rising national-commercial empires.

It is believed that an article that appeared in North China Daily in 1896 was the first reference to the Qing Empire of the Manchus as ‘The Sick Man of East Asia’. The expression immediately resonated with Chinese and non-Chinese alike; it would serve various political purposes while contributing to racial prejudices and stereotypes. As a term of self-abnegation and loathing ‘The Sick Man of East Asia’ was pounced upon by Han Chinese patriots; henceforth, they used it both as a characterisation of Manchu misrule and as a self-deprecating warning about the uncertain future of China itself.

For the next half century political leaders as disparate as Sun Yat-sen, Chen Duxiu, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong offered vastly different nostrums to treat the ills of ‘The Sick Man of Asia’. In the 1950s, just as he was leading China into a harrowing three decades of near terminal decline, Mao Zedong, whose People’s Republic celebrates its seventieth birthday on 1 October 2019, declared that China under the Communist Party had finally sloughed off its past maladies.

The trope of ‘The Sick Man of Asia’ also contributed to a complex body of ideas debated for over a century under the rubric of ‘China’s National Character’ 中國國民性. It is a discussion that has invariably focussed on the ‘inferiority’ or ‘blighted roots’ 劣根性 of the Chinese themselves. As a result, a rich literature on the negative aspects of the collective character of the ‘Chinese Race’ (a concept that itself was invented in the late-nineteenth century) has evolved. In that large body of writing, unappealing social and political behaviour in the Chinese world is dissected and lambasted by writers as various as Li Zongwu 李宗吾 and Lu Xun 魯迅, as well as by modern Taiwan-based critics and satirists like Bo Yang 柏楊, Li Ao 李敖 and Lung Ying-tai 龍應台, not to mention the Mainland writers Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, Li Jie 李劼 and Yu Jie 余杰. All of these writers have critiqued the ‘national psychology (or pathology)’ of China; they have, in particular, pointed out problems that they identify as being rooted in a society dominated by patriarchal social arrangements and autocratic governments for over two millennia.

‘National Character Studies’ was a thriving niche market in the Chinese publishing industry, first in Hong Kong from the 1970s and then on the Mainland since the early 1990s. As China has grown wealthier and stronger, the self-doubts and self-loathing reflected by these ‘China Stereotype’ debates has continued and — unsurprising in a totally self-absorbed nation (something that China shares with other navel-gazers like Japan and the United States, to mention but two) — it has flourished.

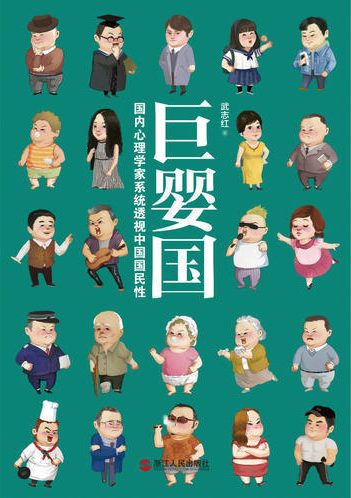

In 2016, Wu Zhihong 武志紅, a Beijing-based psychologist, would offer a broad anecdotal update of this modern tradition of self-absorption in his best-selling Giant Baby Nation: A Mainland Psychologist’s Systematic Examination of the Chinese National Character 巨嬰國: 國內心理學家系統透視中國國民性.

The Giant Baby Republic of China

In recent decades the global reach of the hurt feelings of the Chinese people has attracted attention, as well as a good measure of popular (and, in private, diplomatic) derision.

‘The feelings of the Chinese people’ 中國人民的感情 is a phrase invoked by both the party-state and writers of various persuasions (and constituencies) to protest against perceived slights to the People’s Republic and its interests. It serves also as a ready indictment of ‘The West’ for its historically biased treatment of ‘China’ and ‘The Chinese’ today.

In December 2008, Joel Martinsen of the Beijing-based media group Danwei reported that a Chinese blogger writing under the name Fang KC had scanned the electronic archives of sixty years of the People’s Daily — from 1946 through to 2006 — and discovered that nineteen foreign countries and international organizations had, up to that point, officially ‘hurt the feelings of the Chinese people’. Of these, most had inflicted injury not just once but on numerous occasions.

In his overview of these findings, Martinsen noted that: from 1985 Japan had hurt Chinese feelings no fewer than forty-seven times (and that was before the controversy over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in September 2010!); the USA had done so twenty-three times, starting in 1980, when Los Angeles flew the flag of the Republic of China; NATO no fewer than ten times, mostly in relation to the bombing of the Belgrade embassy in 1999; India seven times, starting in 1986, and generally in the context of border disputes; France five times, starting in 1989; the Nobel Committee four times (again, this was prior to it awarding Liu Xiaobo the Peace Prize in October 2010); Germany three times, starting with a meeting with the Dаlаi Lаmа in 1990; and so on.

All told, one-fifth of the world’s populations has to a greater or lesser extent ‘hurt the feelings of the Chinese people’. It is this mixture of abiding victimhood and the sense of humiliation clad in a reactive pose of high dudgeon and hauteur that often characterises Chinese articulations of nationhood today, be it in the official, or in the personal realm.

As the political scientist William Callahan has suggested, using one of Raymond Williams’s signature concepts in his analysis of the People’s Republic, China is a ‘pessoptimist nation’:

Rather than simply being “a land of contradictions” that suffers from “national schizophrenia,” I think it is necessary to see how China’s sense of pride and sense of humiliation are actually intimately interwoven in a “structure of feeling” that informs China’s national aesthetic. “Structure of feeling” is a useful concept because it allows us to talk about the interdependence of institutional structures and very personal experiences.

— from William A. Callahan

China: The Pessoptimist Nation

Oxford University Press, 2010, p.10

‘As is well known, a very small number of people engaged themselves in anti-government violence in Beijing in June 1989 but failed. . . . The film the ‘Gate of Heavenly Peace’ sings praise of the people in total disregard of the fact. If this film is shown during the festival, it will mislead the audience and hurt the feelings of 1.2 billion Chinese people.’

In our response to the Chinese embassy, we congratulated the comrades on their new-found interest in the visual arts, but nonetheless we queried the methodology they had applied to assessing the feelings of 1.2 billion people of their homeland — a population, we hastened to add, that did not enjoy a meaningful vote or electoral process; has no access to viable democratic institutions; cannot enjoy a free media or, for that matter, basic rights of self-expression.

— these paragraphs are based on my review-essay of Paul Cohen’s 2009 bookSpeaking to History, published by The Harvard Journal of Asiatic Affairs, 71.2 (2011)

***

William Callahan’s remarks on the ‘structure of feelings’ in pessoptimist China bring to mind the work of Sun Lung-kee (孫隆基, 1945-), an historian born in Chongqing and educated in Hong Kong, Taiwan and the United States. In the early 1980s, while still pursuing his studies, Sun published a series of articles in Hong Kong that became the basis of a controversial book titled The ‘Deep Structure’ of Chinese Culture 中國文化的 ‘深層結構’ (Hong Kong, 1982). A broadside aimed at Chinese culture as a whole, ‘Deep Structure‘ was also a pointed critique of the world created, or rather the national character that had been reinforced, on the Chinese Mainland under the rule of the Communist Party. As the People’s Republic, a reinvigorated party-state overseen by yet another autocrat, advances in its march to Wealth, Strength, Power and Redress, Sun’s work, along with the ‘national character’ literature touched on in the above, is worth reconsidering.

In Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, our 1986 book on the culture, politics and imagination of the Chinese Commonwealth, John Minford and I repeatedly quoted Sun’s work. Among other things, we noted Sun’s observation that:

The whole network of social relationships [within Chinese culture] serves as a womb (family, social group, collective, state). And so man, in the sense of a man with a strong ego, has never been born in China. As Lu Xun remarked: ‘True manhood has not yet been created in the Chinese world.’

The Chinese self is permanently disorganized. It has to be defined by leaders and collectives. Clinging to the mother’s womb is the norm for Chinese culture. …

When they go abroad, Chinese tend to stick together, and have nothing to do with ‘foreign devils’. This is how they preserve their peace of mind. The trouble is, they regard this seeking of the ‘mother’s womb’ as a selfless act of collectivism, and look down on others in their struggle for human rights.

— Seeds of Fire, pp.34-35

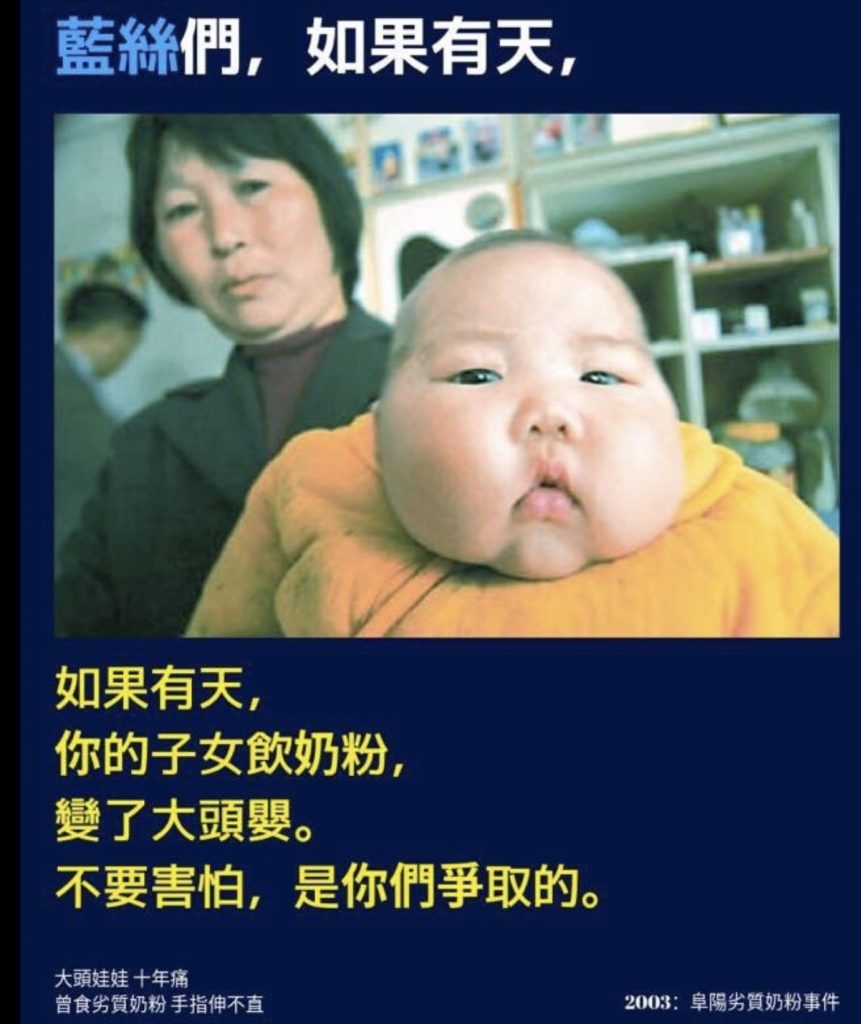

Some thirty years later, Wu Zhihong made similar observations in Giant Baby Nation 巨嬰國. Writing shortly after Wu’s book was banned in early 2017, Zheping Huang noted:

From a social perspective, Wu notes, Chinese people place a strong emphasis on collectivism because they can’t live on their own, both spiritually and materially speaking. They rely on guanxi, or personal connections, to get things done. Meanwhile, they prefer to let powerful figures such as their parents or the government make decisions for them.

— Zheping Huang, ‘A psychology book that argues

China is a “nation of infants” has been pulled

from store shelves’, Quartz, 13 March 2017

Indeed, as Kitty Hung 洪曉嫻 observed in an earlier chapter in our series ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’ in terms that echo Sun’s comments made in the early 1980s:

In China, it seems to be the case that children always have to be ‘controlled’; they can only be permitted to do what their parents will allow them to do. They are ‘taken in hand’ whenever they overstep the mark. It means that that are confined to unfreedom from the moment they are born.

As for the ‘People’, aren’t they no better than children in the all-controlling care of a ‘Father-Mother Officialdom’ [a common traditional term now used for government bureaucrats and Party cadres]? This is the ‘unique national characteristic’ of that Nation of Big Babies [or, Children-Adults].

You can tell the chill of autumn is on the way when the first leaves turn. From the way children are treated all the way up to all that nonsense we are presently hearing about ‘Hongkongers are badly behaved children and the Fatherland is your daddy’. And then there’s Carrie Lam putting on the pose of ‘Kindly Mother’ that comes from the same place.

— from Kitty Hung Hiu Han 洪曉嫻,

‘How Dare You Hong Kong People Resist!’,

China Heritage, 18 August 2019

Bo Yang’s Ugly Chinamen

Bo Yang (柏楊, the pen name of Kuo I-tung 郭衣洞, 1920-2008) was a celebrated essayist, humorist and historian. Repeatedly arrested and tortured during the Chiang Kai-shek autocracy on Taiwan, he was eventually jailed for nearly ten years both as a Communist agent and for attacking Chiang, who he had lampooned as a bald-headed dictator. Following his release from jail in 1977, Bo Yang returned to chiding the authorities and he subsequently generated a new wave of controversy as a result of a speech he delivered at Iowa University in September 1984 titled ‘The Ugly Chinaman’ 醜陋的中國人. Inspired by similar critiques of Japanese culture (one in which national self-reflection is called ‘Nihonjinron’日本人論), Bo Yang’s observations on China — Taiwan, the People’s Republic and Hong Kong — are still frequently quoted. We included passages from Bo Yang’s speech, translated by Don J. Cohn, in Seeds of Fire:

Stuck in the Mud of Bragging and Boasting

Narrow-mindedness and a lack of altruism can produce an unbalanced personality which constantly wavers between two extremes: a chronic feeling of inferiority, and extreme arrogance. In his inferiority, a Chinese person is a slave; in his arrogance, he is a tyrant. Rarely does he or she have a healthy sense of self-respect. In the inferiority mode, everyone else is better than he is, and the closer he gets to people with influence, the wider his smile becomes. Similarly, in the arrogant mode, no other human being on earth is worth the time of day. The result of these extremes is a strange animal with a split personality.

A Nation of Inflation

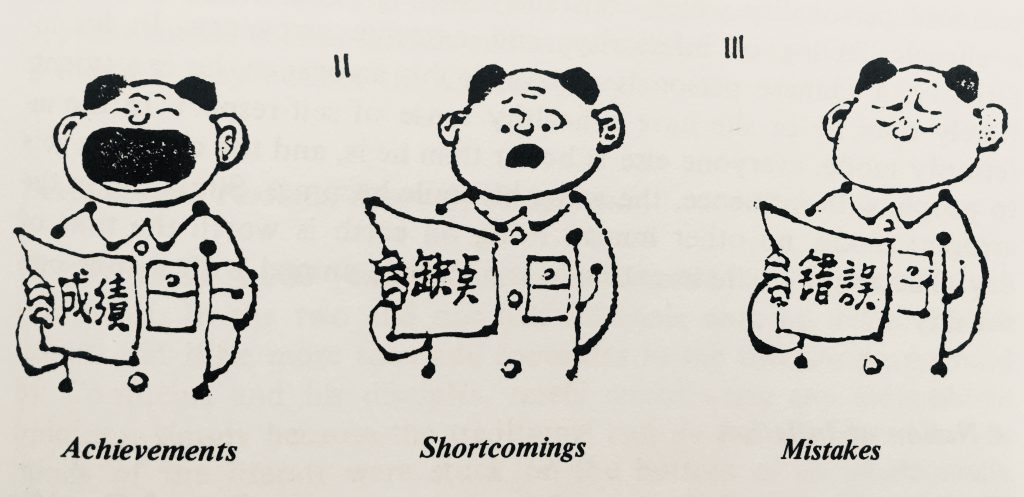

What makes the Chinese people so prone to self-inflation? Consider the saying: A small vessel is easily filled. Because of the Chinese people’s inveterate narrowmindedness and arrogance, even the slightest success is overwhelming. It is all right if a few people behave in this manner, but if it’s the entire population or a majority—~particularly in China-it spells national disaster. Since it seems as if the Chinese people have never had a healthy sense of self-respect, it is immensely difficult for them to treat others as equals: if you aren’t my master, then you’re my slave. People who think this way can only be narrow- minded in their attitude towards the world and reluctant to admit their mistakes. … …

We may not admit our mistakes, but they still exist, and denying them won’t make them disappear. Chinese people expend a great deal of effort in covering up their mistakes, and in so doing make additional ones. Thus it is often said that Chinese are addicted to bragging, boasting, lying, equivocating and malicious slandering. For years people have been going on about the supreme greatness of the Han Chinese people, and boasting endlessly that Chinese traditional culture should be promulgated throughout the world. But the reason why such dreams will never be realized is because they’re pure braggadocio.

As Bo Yang’s ‘Ugly Chinaman’ elicited outrage, debate and delight throughout the Chinese world during the 1980s, on the Mainland, cultural critics like Zhu Dake 朱大可 in Shanghai and Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 in Beijing were exasperated by the gradual revival of State Confucianism under the aegis of the Communists. They warned about the dangers of the ‘Confucius-Yan Yuan Personality’ 孔顏人格, that is, the supposedly perfectible individual which, in practical social and political terms, is was nothing less than the affirmation of the concept of the Sole Adult, the Authority Figure or the Autocrat (formerly Mao Zedong, but in the 1980s Deng Xiaoping).

The idea of the exemplary sage-ruler is sustained by a broad-based socio-political arrangement that requires the constant affirmation, and reinforcement, of rigid hierarchies, mass submission to authority, the championing of a collectivist spirit that suppress the individual, policies that vindicate patriarchal power as well as theories that justify undemocratic, non-egalitarian and anti-pluralistic attitudes and social structures.

Liu Xiaobo in particular warned against the ‘self-enslaving personality’ 自覺的奴性人格 that he felt characterised a Chinese society that had never truly freed itself from the dynastic past, one that was further strengthened under the one-party state. Liu argued that the latest incarnation of State Confucianism threatened to frustrate not only the individual but also the long term health and evolution of Chinese society as a whole. Decades ago, Liu identified and warned against the kind of poisonous and swaggering ‘national character’ most frequently demonstrated today by ‘Patrio-Nasties’ 愛國賊, be they in China or overseas.

A few years after Zhu Dake and Liu Xiaobo published their first critiques, I noted that:

In the early 19903, with the nation’s increased economic growth, there was a new twist in the tradition of self-loathing. People observed that China continued to advance economically without embarking on a drastic reform of the political or social system, and the debate about the ‘humanist spirit’ was part of a cautious attempt by some thoughtful intellectuals to air these concerns in public. Many believed that the acquisition and maintenance of wealth would gradually transform the ‘National Character,’ or at least obviate the need for any major shift in the public perception of it. Consumerism as the ultimate revolutionary action was now seen to be able to play a redemptive role in national life, for it allowed people to remake themselves, not through some abstract national project, but through the self-centered power of possession.

Whereas there was a strong spirit of self-reflection in the 1980s, economic success in the 1990s coupled with restrictions on intellectual debate and political repression encouraged more a mood of braggadocio. The national spirit that was being publicly reformulated in the 1990s was not necessarily based on mature reflection or open discussion but, rather, on a cocky, even vengeful, and perhaps purblind self-assurance that appealed to the mass market.

— Barmé, In the Red, on contemporary Chinese culture, 1999, p.272

Then, in an essay that appeared on the eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, I offered the following:

The absence of genuine political choice and true freedom of the press as a result of the 1989 post-Tiananmen repression has created in effect a society perpetually on the edge of maturation. The population of the urban-boom areas is complicit in a relationship of negotiated repression with the ruling elites. While standards of living have enjoyed unimaginable improvement and the landscape of China has been transformed, many pressing issues of public interest are on hold. Presumably, the unspoken social pact will endure as long as China is prosperous. Enforced harmony, the ‘eight-tooth smile’ [八尺微笑] — one that shows the optimum number of teeth to visiting foreigners — and national celebration are the order of the day…

— Barmé, ‘Olympic Art & Artifice’,

The National Interest, July 2008

Many negative aspects of social behaviour and mass psychology identified by critics of the national character since the late-Qing era as hindering the evolution of China as an equitable and fulfilled modern society are now, paradoxically, reinforced by the country’s party-state as it continues tirelessly to engineer its population through education, propaganda and social policing. This enterprise was launched by the Communist Party during the Yan’an Rectification in the early 1940s, and it is one that has continued relatively unhindered for nearly eighty years (for more on this history, and its contemporary relevance in creating what we have dubbed ‘Homo Xinensis‘, see our five-part series on the subject, ‘Drop Your Pants! — The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again!’ (China Heritage, 8 August-1 October 2018).

***

There are good reasons why Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, the outspoken professor of law at Tsinghua University whose work has featured in China Heritage, refers to the Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping by such ancient terms as 予以人, 當軸, 有司 and 當道. They all indicate a supreme figure, the ‘holistic autocrat’, one who, supposedly, is not merely ‘the only adult in the room’, but is also the only true individual in the nation.

For its part, the Chinese Communist Party regards itself as the ‘end of history’; it sees its ethos as constituting the ‘final solution’ to disputes about the national character; and it regards its autarch as the instrument of history and progress, the embodiment of China’s destiny.

The question posed both by Xu Zhangrun’s incisive critiques of Xi Jinping’s China and by the rebellious city of Hong Kong is: what happens when the Sole Adult and his claque ‘spits the dummy’?

— Geremie R. Barme

Editor, China Heritage

26 September 2019

***

Note:

- The Australian expression ‘to spit the dummy’ is used to describe a truculent individual or an adult who is acting in a childish, immature or unreasonable manner. Xu Zhangrun has used the term ‘Giant Baby’ in his mocking descriptions of Donald Trump, President of the United States of America, a figure whose willful behaviour provides an occidental counterpoint to the case made by the writers below.

***

Further Reading:

- Frank Dikötter, ed, The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997 (PDF)

- Sun Lung-kee (Sun Longji), The Chinese National Character: From Nationhood to Individuality, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2002

- 楊瑞松, 想像民族恥辱:近代中國思想文化史上的“東亞病夫”, 《國立政治大學歷史學報》2005年5月, 第1-44頁

- Thomas Mullaney, ‘Introducing Critical Han Studies’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 19 (2009)

- Mark Elliott, ‘Hushuo 胡說: The Northern Other and Han Ethnogenesis’ (an excerpt), China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 19 (2009)

- Thomas Mullaney, James Patrick Leibold, Stéphane Gros, Eric Armand Vanden Bussche, eds, Critical Han Studies, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012

- Wu Zhihong 武志紅, A Nation of Giant Infants 巨嬰國, Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin chubanshe, 2016 (Chinese PDF)

- Leonora Chu, Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve, New York: Harper, 2017

- Zheping Huang, ‘A psychology book that argues China is a “nation of infants” has been pulled from store shelves’, Quartz, 13 March 2017

- Helen Gao, China’s ‘Giant Infants’, The New York Times, 8 August 2017

- The Editor et al, Homo Xinensis, China Heritage, 31 August 2018

- The Editor et al, Homo Xinensis Ascendant, China Heritage, 16 September 2018

- The Editor et al, Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018

- The Editor et al, Translatio Imperii Sinici, China Heritage Yearbook 2019, January 2019-

A culture that prohibits people from developing ‘the beauty of individuality’, must regard the people who possess this beauty as a threat.

— from Sun Lung-kee, The ‘Deep Structure’ of Chinese Culture

trans. in Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, 1986, p.250

***

China’s ‘Giant Baby Nationalism’

民族主義巨嬰

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated and Annotated by Geremie R. Barme

Reading about a recent academic gathering afforded me some further insights into the relationship between Hong Kong and China, as well as that between Hong Kong People and the Chinese. In particular, it helped me to re-focus on how we can think about the intractable nature of the tensions and conflicts between the two. It also helped me better appreciate the reasons why it would seem to be all but impossible for Mainland Overseas Students and their Patriots ilk to communicate meaningfully with people who have grown up in Hong Kong, let alone debate their differences in a calm and reasonable manner.

Professor Wang Ke of Kobe University has described two kinds of Nationalism. As he sees it, one form of ‘utilitarian nationalism’ is a device aimed at inciting and mobilising mass sentiment for political ends . The other is a more broad-based and encompassing ideology. There is, however, a complex commerce between the two. Well may the power-holders incite patriotic passions for their own immediate purposes, but the fact that they can indulge in such gambits with relative ease is because of the emotive nationalism that has long been inculcated as a substrate in mainstream Chinese thinking.

[Note: Wang Ke (王柯, 1958-) is a professor of modern Chinese political thought at the Graduate School of Intercultural Studies, Kobe University. His work also focuses on China’s ethnic minorities, including the Uyghurs.]

最近讀到剛舉行不久的一個學術研討會的學者們的報告,讓我進一步認識香港與中國、香港人與中國人,為甚麼會有這種幾乎是不可調和的矛盾與衝突,也了解到中國留學生與香港留學生、愛國人士與在香港長大的年輕人何以無法平靜地討論問題甚而無法溝通。

日本神戶大學的王柯教授認為民族主義有兩種,一種是「作為動員民眾的政治工具」,另一種是「作為主流的思想意識」;但這二者也有內在聯繫。掌權者會利用民族主義去動員民眾,而得以利用與操控民眾的原因,是由於民族主義已是中國社會的主流意識。

Generally speaking, when we use the word ‘Nation’ we are indicating something that has come about as a result of the salient agreement between the State and the People, one that is reached on the basis of a sense of shared identity. Nations are also, by and large, formed on the basis of respect for the agreed rights of the individual. The Japanese were first to create a modern term current in Sino-Japanese usage for the Western concept of ‘nation’ by using Kanji 漢字, or Chinese characters to formulate the term 民族, which is pronounced minzoku in Japanese or mínzú in Standard Chinese. The nineteenth-century concept appeared under the auspices of the Tennō or Emperor System of Japan during the Meiji Restoration. Japanese thinkers posited that the ‘nation/ minzoku‘ designated a homogenous race with a millennia-old, consanguineous heritage that shared the same language.

A little later, the Chinese came up with the rubric of ‘The Chinese Race’, 中華民族 Zhōnghuá mínzú [a concept that was influenced by European efforts to forge modern nation-states on the basis of politically malleable racial, cultural and linguistic categories]. This formulation was favoured by the late-Qing thinker Liang Qichao in 1898 in the wake of the Sino-Japanese War. For Liang, ‘the national race’, or mínzú, consisted of citizens who were collectively allied to an identifiable nation-state. Thereafter, under the aegis of the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, ‘China’, or 中華 Zhōnghuá, was accorded a specific and exclusive racial meaning — it indicated a ‘Han Chinese nation’, and ‘The Chinese Revolution’, which was propounded from the turn of the century, had as its aim ‘the expulsion of the barbarian [Manchu-Qing dynastic ruling house and its people] and the revival of China/ 中華 Zhōnghuá’.

Wang Ke also tells us that ‘The Chinese Race/ 中華民族 Zhōnghuá mínzú’ was an invention of self-identifying Han Chinese who deployed the term as part of their political-ideological struggle to seize power from the Manchu-Qing ruling house. As indicated in the above, ‘The Chinese Race’ was a confabulation inspired by the concept of ‘The Japanese Race’ or Nippon Minzoku, although it was one that was even more narrowly defined.

The expression 中華民族 Zhōnghuá mínzú consists of four components:

中 Zhōng is a geo-politial concept indicating a territory;

華 Huá acquired the meaning of an historically unified cultural identity, ambience or heritage; and,

族 Zú indicates a shared ancestry or racial unity.

All of these point to ‘Han People’ [see the references to ‘Critical Han Studies’ in Further Reading above] while 民 mín is a collective of those people in which the above three elements are found in combination and equate to a specific national identity, or ‘nation-state’. It is an identity that posits a uniqueness vis-a-vis an Other, in particular, a hypothetical enemy. In the case of the identity creation of [the initial Chinese race-revolution of the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries] that Other was the Manchu ‘race’ [which itself was an invention of the early seventeenth century]. The Manchu dynastic rulers were a ‘different race’ that could not share nationhood with the Han.

Nation,原意是以國民主權為核心而成立的國家和人民之間的契約關係,基礎是對個人權利的尊重;日本用漢字譯作「民族」後,由於日本單一種族、單一語言、萬世一系的天皇體制,使民族成為血緣關係的闡述。至於「中華民族」這個詞語,最初是由梁啟超在甲午戰爭後於1898年提出的,他所想像的「民族」,是以獨立個人的國民作為構成nation state的主體。到孫中山提出「驅除韃虜,恢復中華」號召革命推翻滿清,就給「中華」賦予排滿並以單一漢族為主體的意涵。王柯認為,漢人革命家為了從滿清手中奪回統治正當性而發明的「中華民族」,比「日本民族」的定義還要狹窄。「中」表達地域概念,「華」表達文明形式,「族」表達血緣關係,這三重元素證明「漢」(「民」)是一個必須具有自己國家的集團(「民族」),並以此區別他者、尋找敵人,「滿」是一個不能與「漢」成為同一種nation的「異類」。

The idealised nation-state as posited within the modern European tradition evolved to champion ideas related to independent polities that were fundamentally [at least according to some theories] dedicated to the pursuit of such universal values as democracy, freedom, equality and human rights. In its Chinese incarnation, however, the nation-state was promoted as a unified [albeit invented] ‘China Race’ that occupied the territory of ‘The Chinese/ 中華民族 Zhōnghuá mínzú’. A nationalism that elsewhere had at its core something fundamentally democratic in aspiration was, in the modern Chinese context [of the soy-sauce vat 醬缸, analysed by Bo Yang] subject to a substantial displacement, one that resulted in the promotion of a form of racial exclusiveness.

[Note: Contemporary ‘Sino-Fascism’ — that is a body of beliefs and doctrines related to racial purity, the demonisation of ethnic minorities, the Chinese Führer-prinzip etc — started gaining popularity from the early 1990s. Authors like the academic Yuan Hongbing 袁紅冰 were passionate about the revival of the ‘China Spirit’ 中華精神 which they declared would rule not only the Pacific Age but the twenty-first century itself. For more on this, see my ‘To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic’ in In the Red, 1999, p.272ff]

The vast majority of Chinese are completely unaware that the lineage of their modern nationalism is deracinated and profoundly distorted. That is why modern Chinese power-holders are able to tout their form of ‘China Nationalism’ as an absolute, culturally unassailable value.

西方原本是為了實現國民主權,保證民主、自由、平等、人權等普世價值而追求的nation-state,在中國就成了由單一民族(漢族)構成的nation state——「中華民族」國家。原本是民主主義性質的nationalism,就這樣在近代中國被偷梁換柱,變成了一個「民族」至上的主義。而絕大多數中國人,不會意識到近代中國民族主義對nationalism的閹割和歪曲。於是近代中國的掌權者們得以大力宣揚「中華民族」的利益就是終極的價值。

There are, however, good reasons why this kind of ‘Humiliated Nationalism’ has been used to form the bedrock of China’s modern national identity — we only have to consider Chinese history from the time of the Manchu invasion in the 1660s and the widespread massacres that followed in its wake [as Qing armies conquered the territory of the former Ming dynasty]; the aggressive incursions of the Western Trading Powers who over time [that is, from the 1840s] carved up Qing-China’s territory into quasi-colonial possessions or spheres of influence; the Japanese aggression from the 1900s and their eventual full-scale invasion of the Chinese Republic in the 1930s, including the Nanking Massacre of 1937. The Communists have [for seventy years] relentlessly devoted time and energy to forging a collective historical memory within China about these disasters and sufferings of their ancestors. Throughout they have tirelessly enhanced a kind of ‘Collective Mentality of Humiliation’. The upshot has been the modern incarnation of a Grand National Purpose and Moral Evaluative Approach [春秋大義, to all political, social and cultural issues] as well as a ‘Chinese Racial Mentality’ that at its core is one that seeks revenge [note our Age of Redress]. This is what has become an overwhelming and absolute Universal Chinese Value.

通過滿清入關大屠殺、列強瓜分和日本侵華和南京大屠殺,以不斷宣傳「祖先遭遇慘禍的集體記憶」,而加強了「屈辱的民族主義」的集體意識。帶有復仇心理的「中華民族國家思想」成了一種春秋大義,民族主義在中國有絕對的價值。

The May Fourth-era liberal thinker Hu Shih declared that:

‘The struggle for individual liberty is in its essence also a struggle for national liberty! The struggle for personal dignity is by its very nature a struggle for national dignity. After all, a nation of liberty and equality cannot be made up of slaves!’

Hu Shih’s concept of nationalism was grounded in a belief in the importance of the dignity of the individual. It is one that has at its core a quest for: democracy, liberty, equality and human rights. The invented ‘China Race/ 中華民族 Zhōnghuá mínzú’ champions instead a narrow and castrated nationalism that promotes homogeneity above all.

胡適說:「爭你們個人的自由,便是為國家爭自由!爭你們自己的人格,便是為國家爭人格!自由平等的國家不是一群奴才建造得起來的!」這是建立在個人主義基礎上的nationalism的初衷:追求民主、自由、平等、人權;而中華民族論就將之閹割成血緣共同體的民族主義。

Gatherings of Hong Kong people held in cities throughout the world in recent weeks to demonstrate support for our Anti-Extradition Bill Protests have regularly been disrupted by Mainland Chinese students studying overseas, as well as by Overseas Patriotic Mainland Chinese. In Hong Kong itself we have also repeatedly witnessed Mainland Patriotic Mobs decrying and attacking our citizens and local journalists. The behaviour of these people, as well as their language, brings to mind a famous epithet from Albert Einstein:

Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.

Einstein wrote these words when German Nazi Nationalism was oppressing individuals in the name of the collective.

Three years ago Wu Zhihong, a Chinese psychologist, published Giant Baby Nation. In it he made the claim that the vast majority of adult Chinese evince the characteristics of infants. These Over-sized Babies are the progeny of the Giant Baby Nation — China.

By contrast, we here in Hong Kong have a society that is made up of mature individuals.

近來在世界各地的香港人反送中集會,都有來自中國的留學生和移民鬧場,香港也不斷有愛國盲眾對市民和記者叫喊襲擊,他們的表現和語言,使人想到愛因斯坦的名言:「好比麻疹,民族主義是嬰兒病。」他講這句話時,正值納粹德國的民族主義,即集體意識壓倒個人主義的時代。三年前,中國心理學家武志紅出了一本書叫《巨嬰國》,指中國大多數成年人,心理水準是嬰兒。這樣的成年人,是巨嬰,這樣的國家,是巨嬰國。

而我們香港,是一個成熟的個體。

***

Source:

- 李怡, ‘民族主義巨嬰’, 《蘋果日報》, 2019年9月19日

***

Bringing Up Baby

巨嬰是怎樣煉成的

To Kit 陶傑

Translated and annotated by Geremie R. Barme

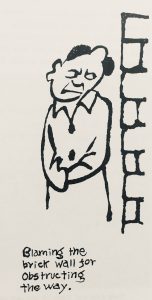

As a result of the chaos created by Carrie Lam’s Hong Kong administration and its backers in Beijing, many international institutions have downgraded the territory’s credit rating because they feel that the autonomous status of Hong Kong [and therefore its legal system and business environment] are imperilled. It comes, however, as no surprise that both Beijing and Lam’s government decry these moves as further proof of ‘the interference of foreign forces in Hong Kong politics’. They supposedly reflect ‘attempts by The West to thwart China’s rise as a strong nation’. Equally unsurprising is the fact that neither Beijing nor the Hong Kong incumbents are capable of seeing themselves as being in any way responsible for the shambles of which they are, in fact, the authors.

林鄭及其後台在香港胡亂攪局,導致多家國際機構以香港正在喪失自治為理由,調低香港的信用評級。中國加林鄭特府自然視之為「外國勢力干預內政」及「西方不想中國強大」之證據,而不會認為香港敗局,是自己的錯。

To be forever blameless and always to see the other party as being in the wrong — these are classical symptoms of an infantile disorder known as ‘self-serving bias’.

[Note: A self-serving bias is ‘any cognitive or perceptual process that is distorted by the need to maintain and enhance self-esteem, or the tendency to perceive oneself in an overly favorable manner. It is the belief that individuals tend to ascribe success to their own abilities and efforts, but ascribe failure to external factors. When individuals reject the validity of negative feedback, focus on their strengths and achievements but overlook their faults and failures, or take more responsibility for their group’s work than they give to other members, they are protecting their ego from threat and injury. These cognitive and perceptual tendencies perpetuate illusions and error, but they also serve the self’s need for esteem.’]

Take, for instance, the case of an infant that is learning to walk. Say it falls over a chair that is lying in its path and starts bawling. Instead of telling the tot to watch out where it is going its mother mollycoddles and pampers the child, crouches down and hits the chair while offering the baby reassurance by saying: ‘Bad chair! It got in our way and tripped my darling over on purpose.’

自己永遠沒有錯,一切都是他人的錯誤,這是一種叫做「自助偏見」(Self-serving bias)的幼稚心理病。譬如,兒童從小受到縱容和寵愛,一名兩歲小兒剛學會走路,被一張橫放着的椅子絆倒,小孩大哭,母親走過來,不教小孩以後長眼睛看路,而是蹲下來,打着椅子,呵護說:椅子壞,攔在路中,絆倒了寶寶。

If a child does well in the exams it will rightly believe that this is the result of hard work. If, however, they get a bad grade, an indulgent parent may mollify their little darling by telling them that it’s just bad luck that the test questions were so unfair; or by reminding the child that they had a tummy ache the day before the test and that had an impact on their performance; or by remarking that it was raining on the day of the exam and there was heavy traffic so they didn’t get to the venue on time and that threw them off their game.

小孩考試成績優良,他會認為這是自己勤力用功的結果。但考試不及格,家長為保護小孩心理健康,告訴他:不要氣餒,試題出得不合理,考試前一天你肚子痛,影響臨場表現;或考試那天下大雨,路上交通堵塞,你到試場遲了十五分鐘,不幸失手。

When a pampered child like that grows into adulthood they will end up being what, on Mainland China, is called a ‘Giant Baby’, a ‘Man-child’.

***

Some people think that the present Chinese policy of one child per family will result in a highly individualistic generation. In fact the opposite may happen. Chinese parents tend to encourage dependence in their children, and if they concentrate all their attention and concern on one child, the Chinese may become even more lacking in personal organization in the future. A man must be fully developed before his life can be a dynamic process; only then can he attain self-actualization in body and mind, can he organize and control his life, his work, his future, his thoughts, his conscience, his interpersonal relationships, etc. Only to such a man are human rights important.

The majority of Chinese are unsure of their own rights. They submit meekly to oppression, and allow others to encroach on their rights. The meekness of the Chinese people makes them particularly receptive to authoritarianism.

— from Sun Lung-kee 孫隆基

in Seeds of Fire, p.311

***

The modern history of China’s Man-Child Nation is one that consists of repeated lessons about humiliation — it is even called ‘a century of humiliation’. The lessons include:

- The burning of the Garden of Perfect Brightness [in 1860];

- The invasion of Beijing by the Eight-Allied Forces [in 1900 to suppress the Boxer

Rebellion]; - The Korean War [against the United Nations/ United States from 1950 to 1953].

They are all taught as object lessons of the crimes of the Imperial Powers. If, however, one takes another, Rashomon-esque, view of these same events, and delves a little deeper into their actual causes and, in the process, propose a more holistic approach to the facts and a more equitable account of the actual events you will be denounced by the Man-Child-in-Chief [the party-state-army supremo Xi Jinping] for advocating ‘historical nihilism’.

這樣的小兒長大成人,即成為大陸流行的所謂巨嬰。巨嬰國的現代歷史課本,百年屈辱一樁樁控訴:火燒圓明園、八國聯軍、朝鮮戰爭,全是所謂帝國主義列強的錯。若有人比較羅生門其他版本,探究因由,提供另一邊的事實與平衡的觀點,巨嬰首領即認定此是「歷史虛無主義」。

When the Giant Babies of China travel overseas they make a scene wherever they go. Let me illustrate my point with an outrageous example from September 2018. Early one morning in Stockholm three mainlanders dragged their luggage into a hotel and demanded that they be allowed to check in early. When they were refused by the hotel staff they reacted in vociferous outrage. When the police were called to remove them the tourists literally screamed ‘Bloody murder!’. All of a sudden, the Giant Babies of China were on parade in the Adult World!

因此巨嬰出國,全球到處製造場面。比較聳人聽聞的一種:凌晨瑞典斯德哥爾摩街頭,三名大媽大叔拖着行李,因強行要提早入住酒店不果,大吵大鬧,警察來維穩,三傻高呼「殺人啦」,片斷哄動嬰兒國和外面的成人世界。

The Hong Kong Tempest that started in June is another case in point — everyone else is to blame:

- Young Hong Kong;

- Social Media;

- Liberal Studies Education (brought in by Tung Chee-hwa);

- Malign Foreign Forces;

- The US Administration and Congress;

- Hong Kong Real Estate Magnates;

- [The magnate] Li Ka-shing…

The blame for the debacle is sheeted home to all of them. As for Carrie Lam-Cheng and the Bumpkin Left, well, they have been blameless throughout.

香港的六月風暴也一樣,萬方有罪:香港年輕人、社交媒體、中學通識教育(是阿董時代搞出來的)、外國勢力、美國政府和國會、香港地產財團、李嘉誠;個個都錯,林鄭和土左,永遠是對的。

Regardless of whomsoever it blames — be it anyone or everyone else — this spoiled brat will never enjoy true authority. It will forever feel badly done by and bullied; it will never grow to maturity.

That’s why Carrie Lam has complained [in a recording of remarks that the Chief Executive of Hong Kong made to a group of businessmen that was subsequently leaked to Reuters]:

‘All those people out there in the streets have made it impossible for me to get my hair done. I can’t go shopping or attend any banquets’.

You might notice the through-line:

‘Me, Me, Me, Me!’

[Note: The Reuters transcript reads:

‘In less than three months’ time, Hong Kong has been turned upside down, and my life has been turned upside down. But this is not the moment for self-pity, although [name redacted] nowadays it’s extremely difficult for me to go out. I have not been on the streets, not in the shopping malls, can’t go to a hair salon, can’t do anything because my whereabouts will be spread around the social media, the Telegram, the LIHKG, and you could expect a big crowd of black T-shirts and black-masked young people waiting for me.’

— Exclusive: ‘If I have a choice, the first thing is to quit’

– Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam – transcript,

Reuters, 3 September 2019]

一切過錯諉於他人,不會令這個撒賴的嬰兒擁有權力,只會令該種巨嬰永遠覺得受欺凌,自己永遠長不大。所以她說:大量市民抗議,我無法做頭髮,我去不了街,我無法出席酒會。

我我我我我。

So the Eight Nation Armies are bullying you today just like they did back in the days of the Manchu-Qing dynasty, isn’t that so? Come off it!

原來八國聯軍今天還把你當做滿清來欺凌圍堵?噢。

The child who refuses to grow up always plays the weakling; how will it ever achieve real authority in a world of adults? It will always be making a woeful racket back there in Economy Class. No matter how often the stewardess has to go back down the aisle to pacify the recalcitrant brat with lollies and games it will keep bawling. Nothing will convince it to stop making a racket. It will blubber, scream and carry on all the way from Beijing to New York. This weak and pathetic creature will always be at the centre of its own bizarre little world.

長不大的嬰孩永遠是弱者,在成人世界怎會享有權力?只嘩哩嘩啦的在經濟艙哭鬧不休。空姐來哄,給牠吃糖,牠還哭;給牠玩具,牠又哭,總之一程萬里雲海之上,由北京飛到紐約,這頭弱小的動物是世界的一個奇異的中心。

***

Source:

- 陶傑, ‘巨嬰是怎樣煉成的’, 《蘋果日報》, 2019年9月19日