A New Sinology Jotting

Chinese festive foods have long been embraced by international cuisine. Spring rolls 春捲兒 chūn juǎn’r and dumplings 餃子 jiǎozi are eaten all year round and around the globe, and moon cakes 月餅 yuè bǐng enjoy a seasonal popularity. Even zòngzi 粽子, the glutinous leaf-wrapped sweet or savory packages that commemorate the long-drowned Qu Yuan 屈原 during the Dragon Boat or Double Fifth Festival, are on the menu. It is unlikely, however, that the humble dish egg-fried rice 蛋炒飯 dàn chǎo fàn, one long since adopted by Chinese restaurants, fast-food outlets and home chefs worldwide, can hope to enjoy internationally the status of edible symbol of gustatory protest that it has achieved in China in recent years.

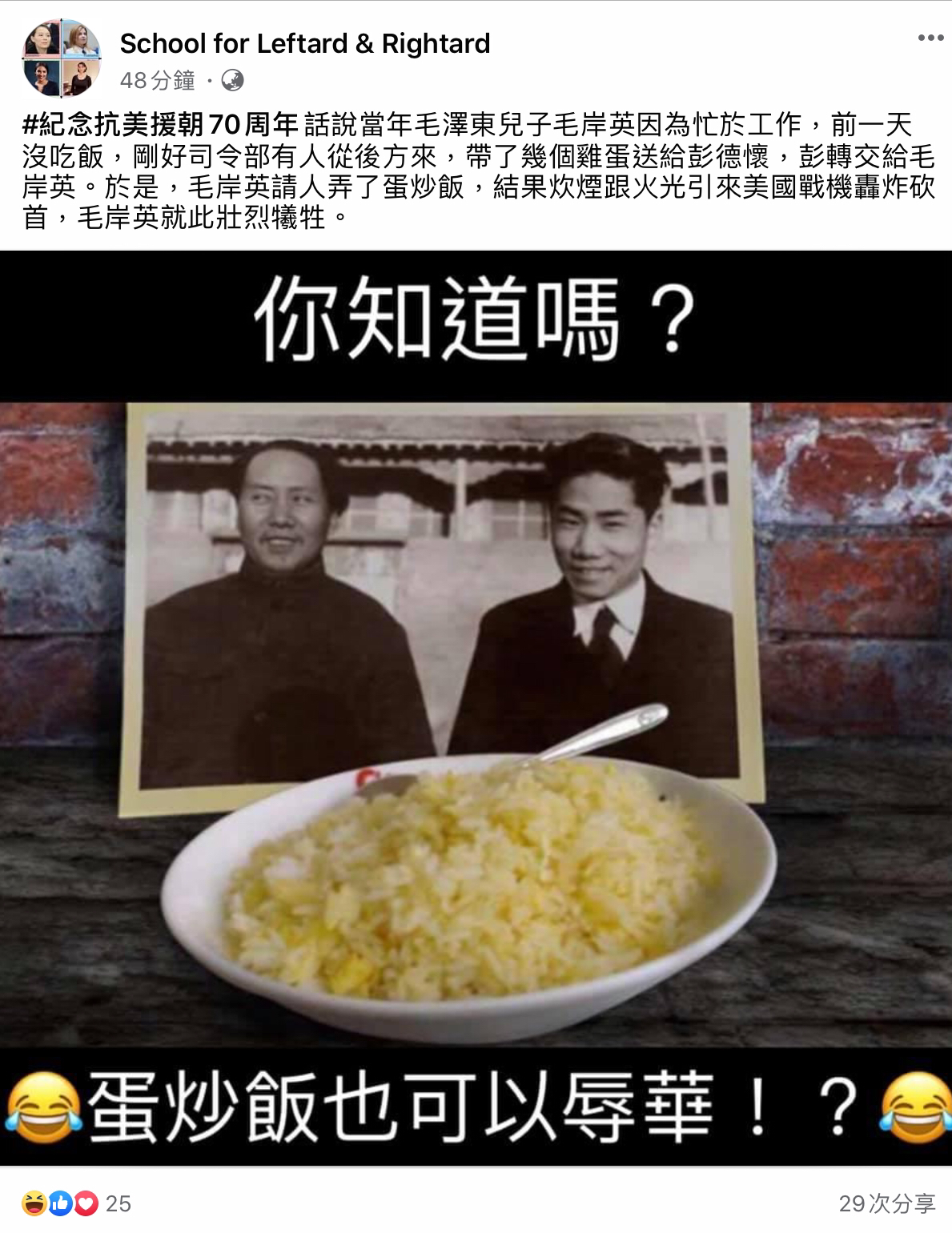

The 25th of November is celebrated annually by China’s anti-Communist cognoscenti as ‘Egg-fried Rice Festival’ 蛋炒飯節 dàn chǎo fàn jié. That is because it marks the day on which Mao Anying 毛岸英, the eldest son of Mao Zedong and Yang Kaihui 楊開慧, the Great Leader’s second wife, was killed during a US air raid in 1950, the first year of the Korean War.

On that day, Anying was at the command centre of the ‘Volunteer People’s Army’ sent by Beijing to support North Korean forces in their titanic struggle with the Republic of Korea in the south. The Chinese were under the command of Mao’s close comrade, General Peng Dehuai 彭德懷. A popular account of the events of that day holds that Peng had given Anying a present of eggs which the young aide de camp took to a makeshift kitchen near the well-protected Chinese headquarters to make a dish of egg-fried rice when an American sortie, alerted to the presence of the enemy by a column of smoke rising from the tent, bombed Mao’s progeny into an early meeting with Marx.

Official Chinese accounts deny the egg-fried rice version of Anying’s end but, in the feverish atmosphere of quasi-Maoist revanchism of the Xi Jinping era, the story has enjoyed considerable currency. Now, the 25th of November is celebrated because, it is argued, had Mao Anying lived, he may well have been groomed by his father to succeed him as Party leader, much in the style of the Kim Il Sung-Kim Jong Il dynasty in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, China’s fraternal socialist neighbour. Since 25 November is proximate to the fourth Thursday of the month, a time when Thanksgiving is celebrated in North America, it is also known as Chinese Thanksgiving 中國感恩節 Zhōngguó gǎn’ēn jié.

Although Mao Anying’s premature death frustrated the possibility of dynastic succession via primogeniture (Anqing 毛岸青, Anying’s younger brother, was mentally impaired), Mao nonetheless supported the political ambitions of his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, who planned to rule in his wake along with her associates, the so-called ‘Gang of Four’. These plans too were frustrated when that clutch of Maoists were detained during a military coup in early October 1976.

***

In 2020, the ‘viral year’ in China’s People’s Republic that has been the theme of our China Heritage Annual, Egg-fried Rice Festival 蛋炒飯節 was controversially celebrated a month early.

The 25th of October 2020 marked the seventieth anniversary of the first military engagement of the ‘volunteer army’ dispatched by newly established People’s Republic of China with troops fighting for what is known as South Korea. Like many other aspects of the 1950-1953 conflict on the Korean Peninsula, the nature of the Chinese intervention was cloaked in obfuscation and deception. All parties involved in the war have distorted the historical record in their own interests. On 23 October 2020, China commemorated what it officially calls a ‘Volunteer Action to Oppose U.S. Aggression and Support Korea’ with a mass gathering at the Great Hall of People in Beijing and yet another dolorous and lengthy ‘important speech’ by Xi Jinping, the head of China’s party-state-army .

Given the ongoing trade and ideological conflict between Beijing and Washington, it was not surprising that Xi Jinping’s speech was pointed and pugnacious (see: (習近平, ‘在紀念中國人民志願軍抗美援朝出國作戰70週年大會上的講話’). As Xi’s Korea-themed fire-and-brimstone speech was released on the eve of Mao Anying’s birthday, the 24th of October, it was unfortunate that a popular online chef by the name of Wang Gang (王剛. 1989-), chose that moment to release a video on how to make Yeung Chow Fried Rice 揚州炒飯. It led to an immediate outburst of patriotic rage and, shortly thereafter, to a counter outburst of support both for Wang Gang and for the Egg-fried Rice Festival.

One quick-witted commentator suggested that another popular egg-and-rice dish should be included in the festival: 親子丼 oyako domburi (qīnzǐ dǎn in Standard Chinese), or ‘parent-and-child rice bowl’ consisting of fried chicken and scrambled egg over rice. The dish, it was suggested, neatly accommodated both Mao Anying and his father. Then, in consideration of the Maos’ Hunanese origins, some suggested that it might be more appropriate for the festival to feature another father-son dish: ‘Smoked Pork Egg-fried Rice’ 臘肉蛋炒飯 làròu dàn chǎo fàn, with Mao père represented by Hunan-style smoked pork 臘肉 làròu.

***

Following a short introductory essay below, we introduce the culinary delights of egg-fried rice by means of a running commentary by ‘Uncle Roger’, a persona created by the comic Nigel Ng 黃瑾瑜, on a risible attempt at making the dish by the renowned TV chef Jamie Oliver. This is followed by Wang Gang’s controversial video of Yeung Chow Fried Rice. In conclusion, we offer a comment on the egg-fried rice kerfuffle by Gou Ge 狗哥, an independent and unflappable commentator based in North America who calls his YouTube channel ‘看中国的狗哥 DogChinaShow’.

***

This essay and the video clips that accompany it is a New Sinology Jotting 後漢學劄記, one of a series composed in the style of ‘jottings’ 筆記 bǐjì or 劄記 zhájì, a genre familiar to readers of traditional Chinese prose. These jottings are essays in the style of New Sinology 後漢學, that is, the study of and engagement with the Chinese and Sinophone worlds from the high to the low, the po-faced official and traditional to the irreverent multiverse of Other China.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 November 2020

***

Related Material:

- Stephen Lee Meyers and Chris Buckley, ‘In Xi’s Homage to Korean War, a Jab at the U.S.’, The New York Times, 23 October 2020

- 蔡幸秀, ‘蛋炒飯辱華!中國知名美食網紅王剛慘遭出征’, 《新頭殼newtalk》, 2020年10月25日

- ‘The Year of the Rooster, On Eating, Injecting, Imbibing & Speaking’, China Heritage, 25 January 2017

- New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記, China Heritage

***

Stir-fry China

One of the simplest Chinese recipes is ‘stirred eggs’ (aka ‘fried eggs’) 炒雞蛋 chǎo jīdàn, which is notably described in extraordinary detail by the linguist Yuen Ren Chao 趙元任. As Chao’s wife, Buwei Yang Chao 楊步偉, remarks in her 1945 book How To Cook and Eat in Chinese 中國食譜 (which, among other things, gave the English language the expression ‘stir-fry’):

‘As this is the only dish my husband cooks well, and he says that he either cooks a thing well or not at all, I shall let him tell how it is done.’

The author then offers Chao’s method (one reproduced by various online writers). For our purposes, the most delectable detail from the famed scholar of the Chinese language is the last paragraph of his recipe:

‘To test whether the cooking has been done properly, observe the person served. If he utters a voiced bilabial nasal consonant with a slow falling intonation, it is good. If he utters the syllable yum in reduplicated form, it is very good.’ ― Y.R.C.

***

炒 chǎo, to fry or stir-fry is central to many cooking techniques, such as: 清炒、爆炒、軟炒、溜炒 、煸炒、乾炒. It was famously used during the 2019-2020 Hong Kong uprising against Beijing in the expression 攬炒 laam5 caau2. As we previously noted:

This Cantonese term, which originated in online gaming, enjoyed great currency during the 2019-2020 Anti-Extradition Law Protests in Hong Kong. It means, to take someone down with you when you are facing defeat/ death/ destruction yourself. In the commercial world the expression is described as a ‘scorched-earth defence’, that is ‘a form of risk arbitrage and anti-takeover strategy’:

‘When a target firm implements this provision, it will make an effort to make itself unattractive to the hostile bidder. For example, a company may agree to liquidate or destroy all valuable assets, also called “crown jewels”, or schedule debt repayment to be due immediately following a hostile takeover. In some cases, a scorched-earth defense may develop into an extreme anti-takeover defense called a “poison pill”.’

A Cantonese-language definition offers the following:

‘If you are going to go down, then “jade and stone will both be destroyed” and the person who is trying to hurt you will end up being hurt just as bad. If you get into a trouble then your persecutor is going to be “broiled in the same wok”.’

攬炒就係同人哋玉石俱焚、兩敗俱傷嘅意思,即係若果自己出事,都要攬住加害者一鑊熟。

In Standard Chinese, the set-expression 同歸於盡 tóng guī yú jìn, ‘to travel the path to obliteration with each other’, expresses a similar sentiment. So too does a line in the 2014 film ‘The Hunger Games: Mockingjay’: ‘If we burn, you burn with us’, which enjoyed a new lease during the protests.

— from the Editorial Introduction to Margaret Ng 吳靄儀

‘Hong Kong 攬炒 — Burning Down the House’

China Heritage, 1 May 2020

Beijing propagandists have their own favoured kind of rhetorical stir-fry. They use the expression 炒作 chǎo zuò, ‘a beat up’, or ‘publicity generating’, as a term of derision to describe any kind of commentary, speculation or analysis deemed to be unfavourable. The present New Sinology Jotting on the Egg-fried Rice Festival would, not surprisingly, be dismissed as beat up in poor taste.

***

***

West Korea

西朝鮮

Xī Cháoxiǎn

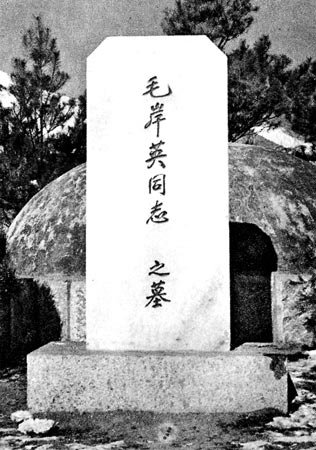

In 2009, only days after the 1 October 2009 celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, then Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao 温家宝, paid a state visit to North Korea during which he visited the memorial to the fallen members of the Chinese ‘volunteer army’ where he laid a wreath at Mao Anying’s tomb. Thereupon, Wen addressed a stone likeness of the dead soldier:

‘Comrade Anying, I have come to see you on behalf of the people of the motherland. Our country is strong now and its people enjoy good fortune. You may rest in peace’.

岸英同志,我代表祖国人民来看望你。祖国现在强大了,人民幸福了。你安息吧。

— from G.R. Barmé, ‘China’s Promise’

China Heritage Quarterly, March 2010

Xi Jinping’s authoritarian rule and dynastic pretension have been such that online wags have observed the similarities between the leaders of Beijing and Pyongyang: a similar doughty demeanor, flatteringly tailored Western suits along with a similar style of humourless and stentorian politics. Revanchist totalitarianism has led people to refer to Xi Jinping’s China as ‘West Korea’ 西朝鮮 Xī Cháoxiǎn. And, although no leader since 1976 can boast of sharing Mao’s bloodline, there have been any number of Mini Maos who have shared the Great Helmsman’s hubris.

Other popular names for the bombastic Chinese party-state include ‘The Bastard Dynasty’ 兲朝, which employs the neologism ‘兲’, pronounced wángba. It is based on the character 天 tiān, ‘heaven’, ‘celestial’, ‘sacred’, reworked as a composite logogram that combines two words: 王 wáng and 八 bā, or wángba, ‘bastard’. During the Qing era, vassal states often referred to the Beijing court as 天朝 tián cháo, the ‘Celestial Court’ or Celestial Empire. The term has been revived to mock the self-aggrandising behaviour of Xi Jinping’s party-state and that in turn has given birth to the expression 兲朝 wángba cháo, which can be construed as the ‘Celestial Dynasty Turned Bastard’.

Another term for the People’s Republic is the ‘Zhao Family State’ 趙國 which has been current since early 2016 as an expression that covers the Communist party-state and its ruling elite. It is an extension of ‘Member of the Zhao Family’ 趙家人, itself a reference to the Zhao Family that features in Lu Xun’s ‘The True Story of Ah Q’ 阿Q正傳 (1922), a famous novella in which Ah Q, a self-deluded Chinese everyman, convinces himself that he is a member of the local gentry family, the name of which is Zhao. Ah Q is repeatedly disabused of his presumption by the haughty Master Zhao 趙太爺, even up to the eve of his execution.

***

Peking Duck

An American plane spotted the smoke made by the Young Lord who was enjoying himself frying up some eggs. Then, Whammo! In one fell swoop his goose was cooked. [Lit. ‘The Young Lord was roasted like a glazed duck’].

.. Lucky for us, the Young Lord ended up as a roast glazed duck, otherwise, China would be as screwed up like North Korea with Fatty One [Kim Il Sung], Fatty Two [Kim Jung Il] and Fatty Three [Kim Jung Un]. That’s how China avoided the fate of North Korea.

小爺沒事炒雞蛋玩,美國飛機一看咋冒煙了,咣一炸,小爺變成掛爐烤鴨了 … 幸虧小爺掛爐烤鴨了,否則中國和北朝鮮一個德性,大胖、二胖、三胖。避免了中國的朝鮮化。

***

Eating Out of a Big Wok

大鍋炒

dà guō chǎo

The dark humour of Egg-fried Rice Festival on 25 November aside, the Korean War was a conflict of immense significance not only for the ongoing entanglement of the United States and its allies in East Asia, but also because, following the frustrated American involvement with the Nationalist Party under Chiang Kai-shek in the 1950s, it contributed directly to America’s support for the Republic of China on Taiwan and the Cold War geopolitics of the region. It is those politics that are still in play some seventy years later.

For the new People’s Republic in China, the Korean War was only one aspect of a militarised politics that included other mass movements that swept away the institutions, ideas and social customs of the defunct Republic of China. These included:

- A support-the-war patriotic education campaign that established the pattern for subsequent coordinated Party-led nationalist zealotry, from sloganising and forced voluntary participation to the contribution of time and money to the relevant cause;

- The first cultural purges, starting with the films Sorrows of the Forbidden City 清宮秘史, which Mao denounced for advocating ‘selling out the nation’, and The Life of Wu Xun 武訓傳, the first film banned in New China. (Although Wu Xun was ostensibly ‘rehabilitated’ in 1986, it was not readily accessible until 2012. Sorrows was recognised as one of China’s most significant twentieth-century films in 2013);

- The attack on Xiao Yemu’s (潇也牧, 1918-1970) short story ‘Between Husband and Wife’ 我們夫婦之間, a mild satire on peasant cadres being seduced by city ways, that was launched by the newly established Literary Gazette 文藝報 under the editorship of Ding Ling 丁玲. Ding just managed to survive the Yan’an Rectification and she was anxious to prove her cultural bona fides, not only to Mao but also to her opponents in the Party. Xiao was the first writer to be attacked in New China and the denunciation of his story cast a pall over the literary scene and set the tone for future ongoing witch-hunts, a process that would reach an apogee in the early Cultural Revolution period, starting in 1964. Xiao never wrote another work of fiction and he died in 1970, a victim of his persecutors;

- The nationwide thought reeducation campaign in the arts and sciences that included all research and educational institutions, and the re-organisation of tertiary education along Soviet lines. Numerous academics who, despite repenting their previous mistaken ideological stance, failed to ‘make the grade’ and were demoted. Some who broke under the relentless pressure of their peers committed suicide;

- The Suppression of Bad Elements throughout the society was a movement during which the Party identified and eliminated class enemies. A Soviet-style ‘rule by law’ system overseen by Peng Zhen and others resulted in mass trials and the execution of some three to five million people. The process effectively wiped out the social structure of rural China. Eventually, in 1953, Liang Shuming 梁漱溟, a respected modernist Confucian social activist, remonstrated with Mao about the wholesale upending of village life. He was purged for his efforts and remained a non-person until the late 1970s. When, in the post-Mao era, Peng Zhen was appointed to carry out ‘legal reform’, few with a memory of the past had little doubt what this really meant; and,

- The Three and Five Anti Movements that, after the 1942-1944 Yan’an Rectification, constituted the first post-1949 purge of the Party ranks and a remaking of the Nationalist era civil service. Over the decades, the Communist Party carried out some fifteen similar large- and small-scale ‘rectifications’ 整風. The latest was launched in September 2020.

Each of the campaigns in the far-from-exhaustive list involved the further entrenching of Communist Party cells in all realms of professional, managerial and social life; the mobilisation of the population by Party zealots in keeping with a timetable determined by Party Central; saturated media propaganda; regular study sessions during which participants were expected to learn by rote Party dogma as it pertained to the relevant campaign; the praise and reward of positive role models; and, the denunciation, demotion and punishment of backward or reactionary figures. Each campaign led to state-sanctioned murder, be it as a result of suicide, quasi-legal processes or due to extra-judiciary execution.

After 1978, although some of the wrongs of the 1950s and early 1960s — known as the ‘First Seventeen Years [of the People’s Republic]’ 十七年, as opposed to the ‘Ten-year Calamity [of the Cultural Revolution]’ 十年浩劫 — were righted, the violent transformation of Chinese society, the purges of rural life, the harsh re-education and disciplining of workers, the wholesale corruption of the legal system, the betrayal of promises made to leading social and political figures, as well as media activists, the ongoing devastation of education, culture and intellectual life were not only justified but also reaffirmed by Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues. After all, they were the co-creators of Maoist China. Any grounded understanding of the People’s Republic in the Xi Jinping era should start with an informed study of the 1950s. The Korean War is but one of the crucial episodes in a history that bequeaths to China today a long, bloody and living tradition.

Indeed, this ‘totalising tradition’ proffers an all-encompassing vision of nation-based human existence, one that claims a valency over every aspect of life, be it individual, familial, that of the group or of the collective. It is a tradition that in each of its permutations reinforces the overall enterprise of systemic subjugation of all forms of diversity and difference for the sake of unity. That unity is, in turn, dominated by a self-renewing political organisation that claims universality for itself. This ‘meal for the masses’ 大鍋菜 dà guō cài is a dish made from a ‘stir-fry in one wok’ 大鍋炒 dà guō chǎo.

For the allied forces led by the United States and acting under the cover of the newly formed United Nations, the conflict on the Korean Peninsula, which ended in a stalemate and an armistice on 27 July 1953, opened the way for a series of regional and ideological wars and standoffs. The uneasy peace in East Asia is once more a focus of international tensions, the complex origins of which are all too often misunderstood, or ignored.

***

Uncle Roger HATE Jamie Oliver Egg Fried Rice

‘You hear sizzling, I hear my ancestors crying.’

— Uncle Roger

- Posted on 31 August 2020. On 20 September, Uncle Roger released another video in which he praised the culinary skill of Gordon Ramsay, another celebrity chef, in preparing nasi goreng, an Indonesian version of fried rice tangentially related to the egg-fried rice under discussion here.

***

Chef Wang Gang’s

Yeung Chow Fried Rice

- Posted on 23 October 2020.

***

No Place in China for this Chef?

Gou Ge on Wang Gang’s Egg-fried Rice

王剛蛋炒飯,中國連一個廚子都容不下嗎?

- Posted on 26 October 2020.

***