Celebrating New Sinology

時過境遷

This chapter in Celebrating New Sinology, which is the theme of China Heritage Annual 2025, features the text of lunch-time remarks that I made in May 2015 at a meeting of China Matters, a Sydney based government adjacent think tank (now defunct). I hosted the meeting at the Australian Centre on China in the World, the research centre at The Australian National University in Canberra which I had founded with the support of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and his government in 2010.

That gathering was held at a time when China’s broader regional and global ambitions were increasingly obvious. Although by then there was ample evidence that Xi Jinping, the self-aggrandising ‘Chairman of Everything’ (as I had dubbed him in 2013), was driving a tectonic shift in Asia and the Pacific, others were not so sure. In fact, Linda Jakobson, the head of China Matters, even suggested that Xi was merely the front man for Party elders who were ‘ruling from behind the screen’. Jakobson, a self-advertised 中國通 Zhōngguó tōng — ‘China mavin’ — was unimpressed by my remarks, as was Bates Gill, her colleague and the head of the American Studies Centre at Sydney University. Gill dismissed my quibbling and insisted that America was in Asia and the Pacific for the long haul. For my part, I remained unmoved by his observations and, with the passage of time, my scepticism has only increased.

In 2012, I had invited Stephen Fitzgerald, Australia’s first ambassador to Beijing, to reflect on the four decades since Canberra had formally recognised the People’s Republic of China. In a speech titled Australia and China at Forty: Stretch of the Imagination, Steve noted what had been obvious for some time:

There is now a serious contest and rivalry across the Pacific between America and China. This is not good for Australia. It’s not our contest, the American national interest in this contest is not our national interest, and taking the US side is not necessary to our relations with the US. This is not to argue that we shouldn’t have a close relationship with the US, or that we should side with China, or ditch a client relationship with the US only to have one with China. We need a close relationship with both and a client relationship with neither.

The hope that Australia would not be the client state of a big power had been expressed by thinkers, strategists, historians and others for decades. I had been aware of the sentiment from my teen years in the 1960s, when Australia was embroiled in America’s debacle in Vietnam. Although I shared an intellectual and emotional sympathy with such a stance, and this varied in intensity over the decades, I never really harboured any illusions.

***

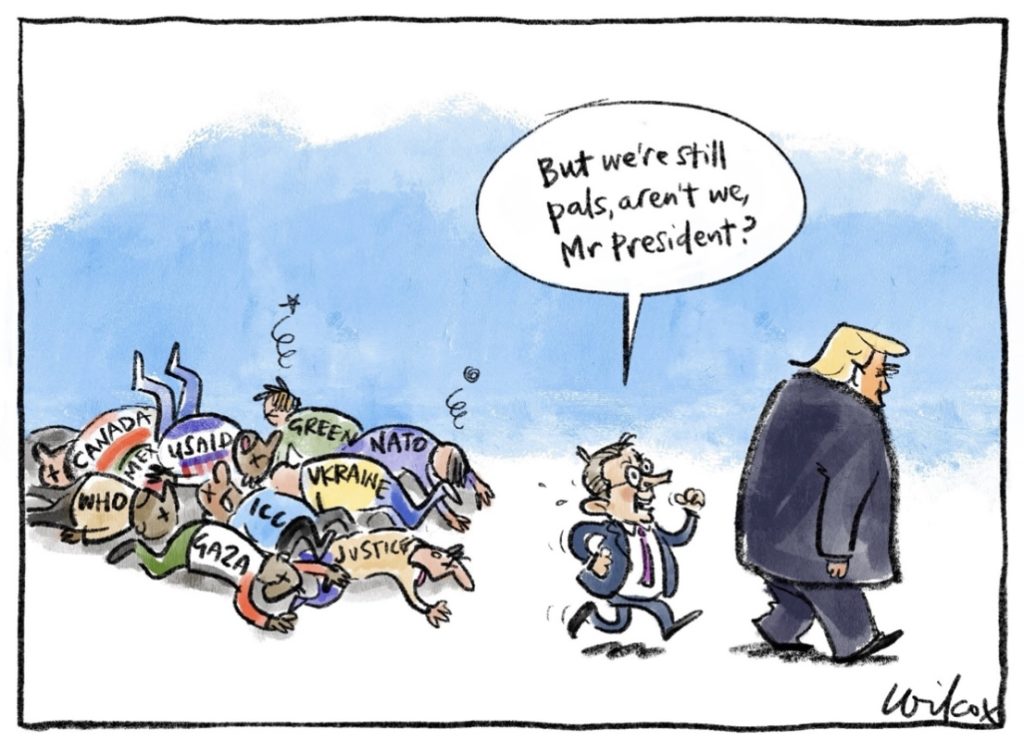

The Chinese rubric of this chapter is 時過境遷 shí guò jìng qiān, ‘that was then, this is now’. Following Donald Trump’s overt tilt towards Moscow, the veteran journalist James Fallows remarked:

If you were a leader (or citizen) in Germany, France, UK, Australia, etc *to say nothing* of Canada, Mexico, Panama, Denmark, and above all Ukraine, could you *possibly* say: “Let’s just stick with the US. In the end, we can trust them”?

Of course not. They have to find a post-US path. …

Australia is now a quarter of the way into the new century yet, like so many other nations, it cannot escape its unfinished twentieth century.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

26 February 2025

***

Related Material in Celebrating New Sinology:

On Australia and Trump’s America in 2025:

- Bernard Keane, Malcolm Turnbull is right. Silence won’t help Australia with Trump, Crikey, 11 March 2025

***

Seventy years on and Australia’s unfinished twentieth century

Geremie R. Barmé

In his memoir, Comrade Ambassador, Stephen FitzGerald recalls his time as a fledgling diplomat in the late 1960s. He characterises Australia’s China policy at the time as being ‘illogical, delusional, and unsustainable’

I wonder what adjectives he might use to describe this nation’s policies today, nearly half a century later?

A 70-year Cold War

In 2012, the 40th anniversary year of the normalisation of Australia-Chinese diplomatic relations, our Australian Centre on China in the World launched its China Story Project, and with it our first China Story Yearbook, entitled Red Rising, Red Eclipse. It wasn’t long before the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China made formal complaints first to DFAT [Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade] and then to us directly about the contents of the book which included an analysis of the purge of the Chongqing party leader and Politburo hopeful, Bo Xilai. I invited our friends at the Embassy to provide a detailed, written version of their critique for publication on our China Story website. Following a long, but unsurprising, silence, I wrote once more to the Embassy explaining our academic stance regarding China. I spoke of universities being home to critical independence, informed debate and openness. After a further silence, I eventually published my letter in December 2012; it was our Centre’s final act of commemoration of that anniversary year.

In an editorial introduction to my letter which I entitled As If, I wrote:

The Australian Centre on China in the World comports itself with simple clarity of purpose; we treat our colleagues, collaborators and interested parties, be they in China or elsewhere, academic, official, private or otherwise in an even-handed, open and frank manner. We believe that it is important to act as if the People’s Republic had already sloughed off the vestiges of Cold War-era and Maoist attitudes, behaviour and language. We engage with the People’s Republic as if it enjoyed an environment like that of any other mature, open and equitable society. We treat with due consideration and respect responses to our work as if they were expressed with the aim of engaging in forward-looking and open intellectual debate and exchange. It is my belief that it is important to respond to official Chinese views of our academic work as if such comments and criticisms were not a result of ideological bullying nor merely the product of fearful bureaucratic fiat or the desire to avoid possible official embarrassment. We act as if the rhetoric of friendship, understanding and shared concerns were a reality.

[Note: A Letter to the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China, The China Story, 31 December 2012. Emphasis added.]

That was December 2012, one month after the rise of China’s party-state leadership under Xi Jinping, the man I like to call China’s CoE, ‘Chairman of Everything’.

Elsewhere, I have suggested that China is still struggling with the legacies of its unfinished twentieth century: a century that promised not only political independence and economic strength for that country, but also democracy, human rights, media openness and social justice. But then, the twentieth was a century of broken promises. Today, however, I am more interested in asking:

Do we too, here in this part of the Asia-Pacific, not also tussle with our own unfinished twentieth century?

This year, 2015, we mark a different kind of commemoration than that of diplomatic normalisation; it is a commemoration of the end of hostilities in Asia and the Pacific resulting from Japanese imperial expansion. It is a year that recalls the cessation of overt war and the establishment of a new order in what was once frequently referred to as our ‘Near North’.

The year 2015 also marks the centenary of the ANZAC disaster at Gallipoli, what for many in Australia is now regarded as the crucible for the birth of one kind of militarised, if tragic, national identity.

The pall of San Francisco

Recently, our Centre on China in the World hosted a workshop organised with colleagues working on East Asia-Korea, Japan and China-and the abiding legacy of the San Francisco Treaty system. That is the regional system of power relations, territorial settlements and protocols that came about as the result of a peace treaty concluded by the Allied Powers with Japan in 1951, signed in San Francisco. Predominantly negotiated by the United States (although there were 48 signatories), that treaty bequeaths to us, all of us in this region, the knotty problems which form part of what is also our unfinished twentieth century.

[Note: See Kimie Hara, ed., The San Francisco System and Its Legacies: Continuation, Transformation and Historical Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific, London: Routledge, 2015.]

I don’t have time to go into all of the vexatious issues generated by the San Francisco Treaty system, but I must note that the most troublesome East Asian territorial issues, regional disputes and conundrums of recent years all have their origins in a treaty signed under the tutelage of America, without the active participation of a key wartime ally, the Soviet Union, with a Japan that was occupied by US forces, a Korea rent by civil war, and without the participation of representatives of either the Republic of China in Taiwan or the newly established People’s Republic of China.

The spate of diplomatic normalisations of the 1970s saw many of the San Francisco issues revisited, but many remained shelved or, by and large, unresolved. And it is with these that we live, struggle and stumble forward today.

Sadly, although we advertised the workshop widely, few colleagues from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) or Defence could find the time to attend; ah, the ironies of contemporary applied public policy: people are too mired in the quotidian minutiae of bureaucratic management and dealing with issues of the moment to find time to learn about the origins of the very problems with which they tussle on a daily basis.

And here we are, with a situation recently described so eloquently by Stephen FitzGerald:

Southeast Asia and Australia are objects of rivalry between a China intent on restoring what it sees as its rightful and historic place in the sun and a United States intent … on blocking or containing China’s ambition …. This gargantuan contest challenges Australian policy thinkers to ask how we should respond strategically, in our interests.

[Note: Stephen FitzGerald, Security in the Region, Pearls and Irritations, 11 May 2015.]

The favourite verb that policy wonks and the popular media use to describe what masquerades as Australian strategic thinking in regard to the People’s Republic of China, and I use the expression with a note of derision, is ‘to hedge’. That is, in a Grand National tradition as venerable as that of the ANZACs, we want ‘to have two bob each way’: to bet on China’s continued economic efflorescence (much to our gain) and relentless American regional dominance and military paternalism (much to our peace of mind). Thus, hedging our way forward, straddling a barbed-wire fence of regional reality Australia, sometimes the Deputy Sheriff to American interests in the Indo-Pacific, sometimes in the guise of a semiautonomous entity, engages with our part of the world and seeks security from outside it.

But how is this country to respond now, today, to China under a focussed, canny and calculating leadership directed by CoE Xi Jinping, and deal with the countervailing Chinese policy ‘to wedge’: that is, to engage on all fronts with the regional and global order?

But, before saying more about this, let me comment on what the Chinese extol as Xi Jinping’s ‘acupuncture diplomacy 点穴式外交. The official definition of this new style of national outreach is that Xi undertakes ‘short, equitable, fast’ 短、平、快, high-efficiency official visits to regional and other countries. Each trip is lauded as having acupuncture accuracy that opens up blocked issues and through the careful and calculated application of pressure on sensitive acu-points it leads to a broad and positive outcome, a healthy flow of Qi.

But there is another side to this kind of policy approach and it relates to China’s at times seemingly erratic behaviour in the region over recent years. Xi’s ‘acupuncture-style foreign policy’ has another dimension, that of action, reaction, recalibration, withdrawal. As I write in the introduction to our latest China Story Yearbook, this:

is a disruptive style that recalls Mao’s famous Sixteen-character Mantra 十六字訣 on guerrilla warfare: ‘When the enemy advances, we retreat; when the enemy makes camp we harass; when the enemy is exhausted we fight; and, when the enemy retreats we pursue’ 敌进我退敌驻我扰 敌疲我打 敌退我追。It is an approach that purposely creates an atmosphere of uncertainty and tension.

Trained myself at Maoist universities in China in the 1970s, you’ll hardly be surprised to learn that I conclude that paragraph above with the following statement: ‘To appreciate the mindset behind such a strategy students of China need to familiarise themselves with such Maoist classics as “On Guerrilla Warfare”《论游击战》and “On Contradiction”《矛盾论》.

Shared destiny: between hedging and wedging

Earlier this week, the Chinese media reported that, since coming to power, Xi Jinping has used the expression ‘the community of shared destiny of humanity’ 人类命运共同体 some 62 times. The People’s Daily claims that this expression encapsulates China’s ‘global vision’ 全球观 and its, not to mention humanity’s, path to the future.

Of particular interest to us in the Asia and Pacific region are the ideas crystallising around the formulation Community of Shared Destiny 人类命运共同体 that Xi Jinping first clearly articulated in October 2013 in regard to China’s relationship with what it terms ‘peripheral nations’ 周边国家. ‘Shared destiny’ is a powerful concept; it overlaps with a plethora of Marxist-Leninist ideas, Maoism and collectivist theories in China. This is why we chose to investigate the concept in our 2014 China Story Yearbook, the title of which is Shared Destiny.

Shortly after Xi’s October 2013 speech was published, I bumped into Peter Varghese, Secretary of DFAT, at a gathering at Parliament House here in Canberra. I told Peter about the speech and shared my sense of its importance.

I remarked that the concept of a Community of Shared Destiny, and how Xi described it, reminded me of the announcement in 1940 by the imperial Japanese government of the creation of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere 大東亞共榮圈. More to the point, I remarked, was that as China operationalised some of its rejigged traditional ideas about power in the region, Australian policy thinkers would need to consider carefully how China was ranking its regional partners and how one would negotiate a relationship with this nebulous new ‘community of shared destiny’, one that I suggested would be a cornerstone of Xi’s regional policies. Obvious questions require consideration: in this Community of Shared Destiny, who is in and who is out? How is this world being ordered with or without our understanding of it or influence over it? How are mindsets determined from the birth of the San Francisco Treaty system helping and hindering our reconsideration of the neighbourhood?

Indeed, it didn’t take long for a very practical case in point to appear: that of Australia’s participation in China’s recent regional economic initiative, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Australia decided, virtually at the last minute, to opt in, but in so doing it acted with undue haste following a clumsy period of hedging which followed on a clever period of Chinese wedging (in particular surrounding the Sino-Australian Free Trade Agreement and Xi Jinping’s November 2014 state visit to Australia). And, despite the kerfuffle unfolding in the South China Sea, will this be a pattern of Australian responses to China’s long-term rise: we hedge and get wedged in return? Or, as so many of those here today ponder: are there ways of thinking in the longer term, and not merely in the context of the historically determined and transactional?

No peace in evolution

But then there are the grim and pressing realities of the Xi Jinping era that make dealing with China more confronting than ever: for it is a ghastly time of renewed social repression, intellectual asphyxiation and party-state desperation.

Our national interest is one thing, but since 1989 and the crushing of the Protest Movement in China, the Chinese authorities have clearly and repeatedly stated that they remain alert and opposed to the ‘peaceful evolution’ 和平演变 policies of the US and the West dating from the 1950s, policies that support the growth of civil society, the undermining of one-party tutelage, and the gradual transformation of China into a market democracy. Under Xi Jinping official opposition to peaceful evolution has become once more articulate and clarion (don’t forget it was the main thrust of Chinese local policy from 4 June, 1989 up to 1992).

The main author of America’s peaceful evolutionary policies aimed at the socialist camp in the 1950s was the US Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles.

Dulles was also one of the main architects of the San Francisco Treaty system. The view, one seemingly affirmed by the eventual decline of the Soviet Union over 30 years following Dulles’ death, is that this policy works. Today, contemporary evolutionists are not as sanguine, for they believe more in cataclysm than gradualism. They posit that China too is heading towards collapse. This revived school of ‘Collapsism’, championed most recently by my friend David Shambaugh, suggests that the Chinese party-state is heading towards oblivion. This encourages us to veer away from long-term planning in regard to China-related regional security because the Commies only have a short-term tenure. But, then, we are going to have to appreciate that whatever might come out of China, even after the Communist Party, will not be a pretty or winsome thing. And whatever it might be, it’s not going to be what the bien pensant expect.

The US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles played a key role in the creation of the San Francisco Treaty system in the early 1950s; later in that decade, he was the proponent of the US policy of peaceful evolution. It was something that obsessed Mao Zedong, just as it obsessed Deng Xiaoping, and now it obsesses Xi Jinping. This is a lesson from history; an unfinished history; the unfinished twentieth century that is central to Australia’s alliance with the United States.

We here in Australia should be clear-headed about just what the historical stakes are in the US-China contestation and how our post-War identity and 70 years of history and choices are bound up with what continues to unfold in our region.

But, then again, I’m an historian, and it’s quite possible that you will think that everything I have said is ‘merely academic’. In that case, bon courage.

***

Source:

- Geremie R. Barmé, Seventy years on and Australia’s unfinished twentieth century, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 69:6 (2015): 645-650