Spectres & Souls

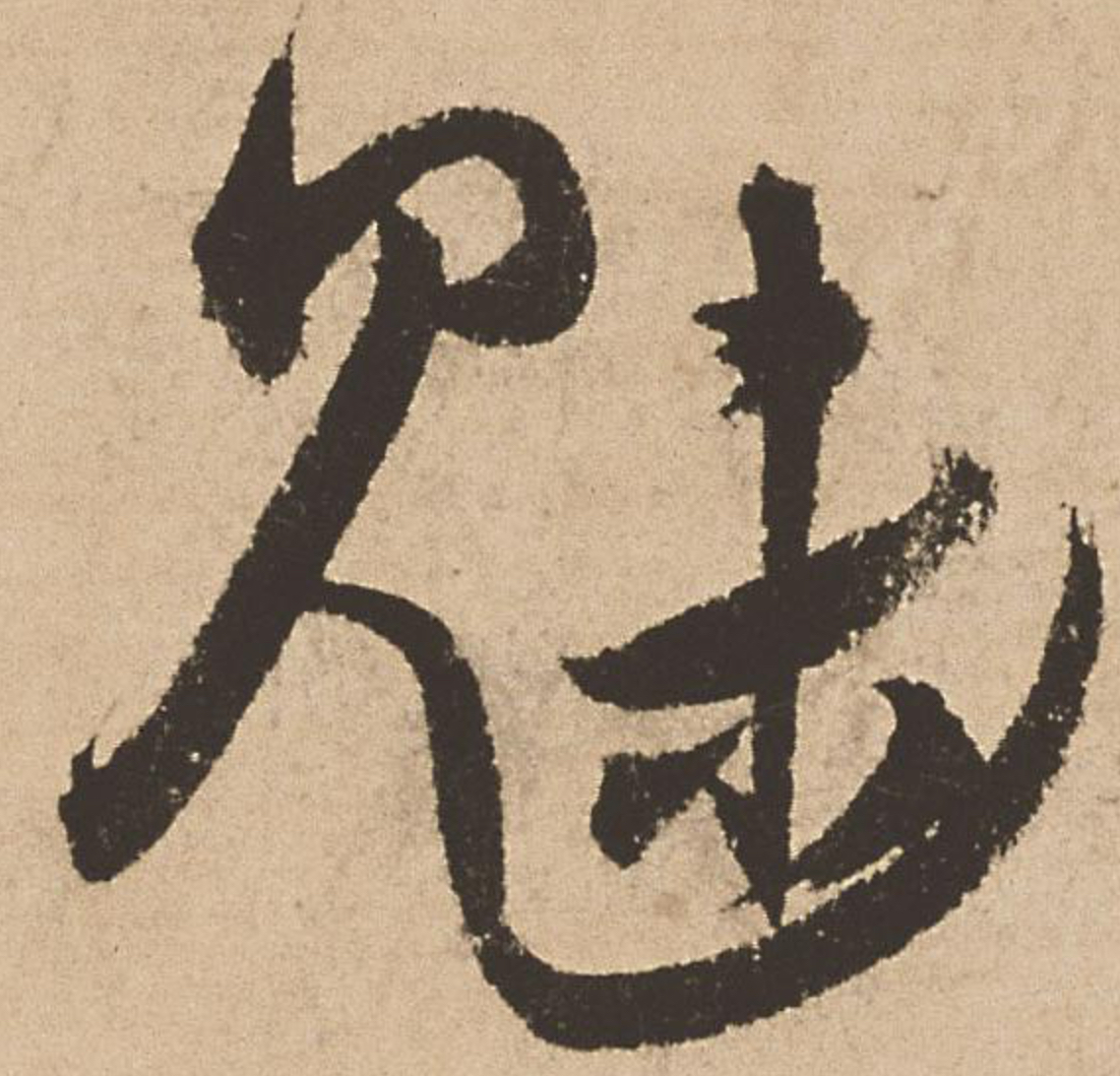

魑魅魍魉

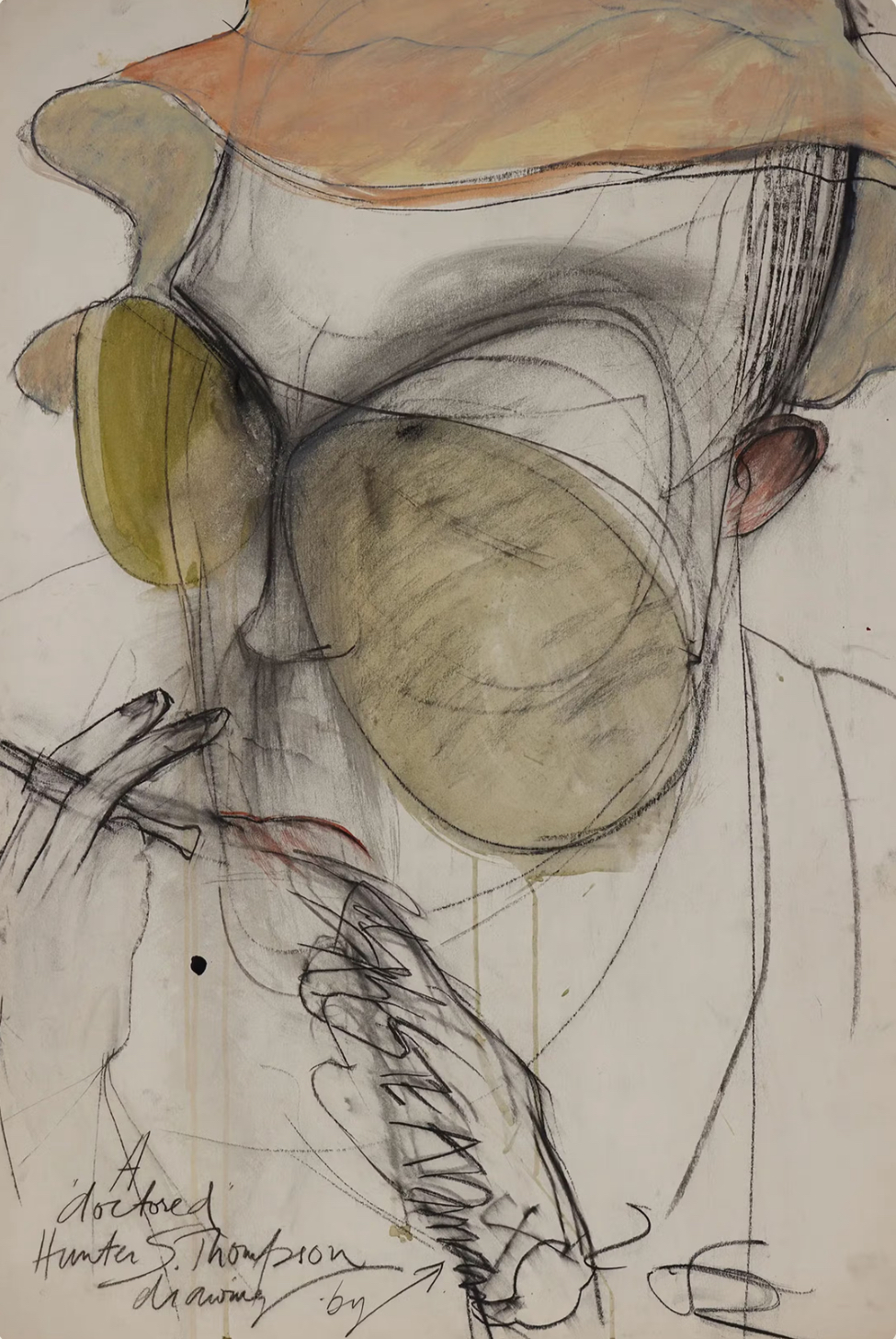

‘A hubris-crazed monster from the bowels of the American dream with a heart full of hate and an overweening lust to be President.’

The gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson’s description of Richard Milhous Nixon resonates today, five decades after Nixon’s resignation as U.S. president in August 1974 and thirty years since his demise in 1994. (I remember listening to Nixon’s resignation speech on 8 August 1974, the same day that my Chinese teacher Pierre Ryckmans/ Simon Leys told me that I’d been awarded a scholarship to study in Beijing.)

In a scathing obituary for a man who both fascinated and repelled him, Thompson wrote that Nixon:

… represents that dark, venal and incurably violent side of the American character that almost every country in the world has learned to fear and despise. Our Barbie-doll president, with his Barbie-doll wife and his boxful of Barbie-doll children is also America’s answer to the monstrous Mr. Hyde. He speaks for the Werewolf in us; the bully, the predatory shyster who turns into something unspeakable, full of claws and bleeding string-warts on nights when the moon comes too close …

Perhaps, in what Yascha Mounk has called the Trump Era, it is time to re-read Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, described by one writer as

one of the most prophetic warnings ever written about American politics. A death letter directed at the schizophrenic duality of the national character, the slimy stock poltergeists who chronically haunt us, and our credulous need for both authenticity and artifice. … [It is] best understood as a road map of spiritual tragedy and cultural decline. A bildungsroman about human limitation, our allergy to the truth, and the importance of trusting your instincts.

— Jeff Weiss, Hunter S. Thompson Was a Weird Visionary, Tablet, 23 October 2024

Nixon, the Republican incumbent, won the 1972 election with a landslide victory that gave him 60.7% of the popular vote, the largest share of the popular vote of any Republican candidate and nearly 10% more than Donald Trump’s vote in November 2024.

Or, perhaps one should rewatch The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, Bertolt Brecht’s 1941 ‘parable play’, a not-so-funny satirical allegory about the allure of fascism and the rise of Adolf Hitler. Since 2020, the most famous line in Brecht’s play has had a haunting resonance:

Do not rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.

But, back to Nixon, about whom Hunter S. Thompson said:

He was the real thing — a political monster straight out of Grendel and a very dangerous enemy. He could shake your hand and stab you in the back at the same time. …

He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president. Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning. … Richard Nixon was an evil man — evil in a way that only those who believe in the physical reality of the Devil can understand it. He was utterly without ethics or morals or any bedrock sense of decency. Nobody trusted him — except maybe the Stalinist Chinese, and honest historians will remember him mainly as a rat who kept scrambling to get back on the ship.

… You don’t even have to know who Richard Nixon was to be a victim of his ugly, Nazi spirit.

He has poisoned our water forever. Nixon will be remembered as a classic case of a smart man shitting in his own nest. But he also shit in our nests, and that was the crime that history will burn on his memory like a brand. By disgracing and degrading the Presidency of the United States, by fleeing the White House like a diseased cur, Richard Nixon broke the heart of the American Dream.

— Hunter S. Thompson, He Was a Crook, Rolling Stone, 16 June 1994

For all of that, it is still worth remembering that during the 2004 US presidential election cycle — ten years after Nixon’s death — Thompson declared:

[Richard] Nixon was a professional politician, and I despised everything he stood for—but if he were running for president this year against the evil Bush–Cheney gang, I would happily vote for him.

Hunter S. Thompson carried out a ten-year crusade against American fascism, he’s gone and its back in the form of Donald J. Trump, a man dubbed by Bret Stephens of The New York Times as ‘Benito Milhous Caligula’, someone who combines the fascism of Benito Mussolini, the paranoia of Richard Milhous Nixon and the moral depravity of the Roman emperor Caligula.

***

In this installment in Contra Trump, our mini series on the 2024 US elections, we consider another contender in the 1968 presidential race. Governor of Alabama and a proud segregationist, George Wallace (1919-1998) ran against Nixon and Hubert H. Humphrey as a third party candidate. For the historian Dominic Sandbrook, Wallace’s race and rhetoric were precursors to Trump’s 2024 electoral bid, something that he addresses in Aberration? Far from it. Trump has deep roots in America’s past, reprinted here from The Times. Sandbrook further explains his thesis in America in ’68: George Wallace, The First Donald Trump, an episode of The Rest Is History podcast.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

11 November 2024

***

On Hunter S. Thompson

- Timothy DeNevi, Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism, PublicAffairs, 2018

On the 1968 Presidential Campaign

- Joe McGinniss, The Selling of a President, Trident Press, 1969

Nixon in China Heritage

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium Appendix V 朝 — Nixon in China, consisting of nine sections: 撼 — A Week That Changed The World; 見 — A storied Handshake, an excised Interpreter & a muted Anthem; 蒞 — Nixon’s Press Corps; 迓 — ‘Welcome to China, Mr. President!’; 有目共睹 — 1978-1979, Year One of the Xi Jinping Crisis with the West; 迥 — Dissing Dissent; 鞭 — The President & The Chairman in Retrospect; and, 書 — A 2012 Letter to the Chinese Embassy

***

Contra Trump 2024

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

***

Aberration? Far from it. Trump has deep roots in America’s past

Dominic Sandbrook

One day in the spring of 1964, George Wallace came to Milwaukee’s Serb Memorial Hall. Best known for his ferocious defence of racial segregation, the pugnacious governor was a long way from home. Milwaukee, the largest city in the midwestern state of Wisconsin, is almost 1,000 miles from Wallace’s natural habitat, the sweltering cotton fields of Alabama.

So to prepare for his primary challenge to President Lyndon Johnson, Wallace’s aides had painted an American flag over the usual Confederate flag on his gubernatorial plane, and had changed his slogan from “Stand up for Alabama” to “Stand up for America”.

But there was no disguising his drawl, the unmistakeable sign of an outsider from the very furthest reaches of the Deep South. And as the little man with the slicked back hair stepped up to address a crowd of largely Polish-American voters — mechanics, repairmen, brewers, toolmakers — none of the watching reporters expected to see a great meeting of minds.

What followed was one of the great unheralded landmarks in American political history. To the reporters’ surprise, Wallace barely mentioned his favourite subject, race. Instead, he talked about the swamp of Washington, the tyranny of unelected judges, the cancer of elitist arrogance, the scourge of federal interference.

Ordinary working Americans, he said, had been betrayed by “pointy-headed professors”, “bearded beatnik bureaucrats”, “federal judges playing God” and the “liberal sob sisters” of the mainstream media. He promised to clean out the communists in the State Department, and to scrap all laws favouring minorities, criminals and freeloaders. And whenever he paused for breath, the audience rose to cheer him to the rafters. One reporter counted 34 ovations in just 40 minutes. It was a performance of which Donald Trump would have been proud — and that, of course, tells its own story.

Wallace never won the presidency; indeed, he didn’t even win the Wisconsin primary. But he was far more successful than anybody had anticipated, and as an independent presidential candidate four years later he won five states and ten million votes. Liberal commentators never knew how to handle him. Some, appalled by his rambling, disconnected but electrically aggressive speeches, saw him as America’s Hitler, while protesters tried to disrupt his rallies by shouting “Sieg Heil!” Others, laughing at his shiny suits, his greasy hair, his air of cheapness and vulgarity, treated him as a fraudster, a shyster, a political conman.

But it took the novelist Norman Mailer, a waspishly astute observer of American politics, to recognise that Wallace might not be an aberration or a freak, but the beginning of something profound. The voters of suburban America, he wrote in 1968, might not be ready for Wallace. But they were “waiting for a Super Wallace”. They discovered him in 2016, and this week they found him once again.

Donald Trump’s supporters and detractors alike often claim that the first man to regain the presidency since Grover Cleveland in 1892 is a unique phenomenon, untethered by the laws of political physics. And so the comparison with the race-baiting governor of one of the bastions of the old Confederacy might sound offensive to some Donald Trump supporters. But the rhetorical and aesthetic parallels — the long lists of enemies, the indictment of Washington bureaucrats, even the hair and suits derided by East Coast critics — are too striking to ignore.

The comparison with Wallace is a reminder that Trump and Trumpism are deeply rooted in American political history. His critics think of him as abnormal, a break from the pattern, and in one or two respects they are right.

No president in US history has ever displayed such scorn for the conventions of democracy or such contempt for the basic decencies of political life. But Trump’s anti-Washington populism would have been instantly recognisable to the men and women in the Serb Memorial Hall in 1964.

Even his style, such a contrast with the polished oratory of Barack Obama or the vanilla pieties of Kamala Harris, is nothing new. In his uncannily prescient biography of Wallace, The Politics of Rage, the historian Dan Carter writes that he was brilliant at tapping “his audiences’ deepest fears and passions … in a language and style they could understand.

“On paper his speeches were stunningly disconnected, at times incoherent, and always repetitious. But Wallace’s followers revelled in the performance; they never tired of hearing the same lines again and again.”

And that in turn drew on a long tradition of American political oratory, not least in Wallace’s native Deep South. For as Carter notes, Wallace was inspired by a political mentor called (inevitably) Big Jim Folsom, whose own speeches were a blend of “exaggeration, hyperbole, ridicule and a kind of country sarcasm that mocked his enemies”.

So when Trump’s critics claim, as they so often do, that “this is not America”, they are quite wrong. Everything about him, from his persona and rhetoric to the hopes and hatreds of his supporters, is very American indeed.

None of this should be surprising. A populist thread has run through American democracy since the very beginning, from the slaveowner Thomas Jefferson’s idealised republic of yeoman farmers to the scandal-plagued, Indian-slaughtering Andrew Jackson’s appeal to the muscular nationalism of the “common man”.

Suspicion of government is as old as the United States: anybody who thinks that Elon Musk invented conspiracy theories should take a long look at the Declaration of Independence, with its luridly exaggerated attacks on the supposedly tyrannical George III. And although American populism and paranoia have a flavour all of their own, they are hardly unique. All nations have their own pathologies, even our own.

Yet populism and paranoia are not the whole story, and we should know better than to dismiss Trump as a fascist in a comically ill-cut suit. Demagogic abuse and aggressive nativism have always been central elements of his repertoire. Defenders who deny his dark side are just as deluded as critics who see him as Hitler reincarnated. But when you dig into the data of this second and most remarkable victory, a complicated picture emerges.

The single most important decisive issue in the 2024 election was not immigration but the economy — and in particular, the punishing effect of inflation on ordinary working-class and middle-class Americans. Trump gained ground among every single demographic group, with the exception of the very richest.

For all the talk of his misogyny, or even the galvanising effect of the overturning of the Roe v Wade abortion ruling, he won 46 per cent of women, a stronger showing than in 2020. And perhaps most remarkably, he increased his strength among Latino voters by 14 per cent, and doubled his share of young black men. Whatever you think of him, it’s far too simplistic to see this as the electoral performance of an American Hitler.

Given these results, is it really true that Trump has fundamentally remodelled the Republican Party? Not entirely. The electoral map, which shows the heartland of the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains and almost the entire south splashed with Republican red, is not radically different from the map half a century ago, in the age of Richard Nixon. Indeed, the comparison with Nixon isn’t such a bad one.

Nixon, like Trump, had an uncanny ability to needle and outrage idealistic, high-minded liberals who regarded him as the devil incarnate. Like Trump, he was often compared to Hitler. One notable cartoon of the 1970s showed Hitler in full Nazi regalia, holding a Nixon mask. Like Trump, he drew criticism for his gauche dress sense and awkward manners; like Trump, he was even mocked for the quality of his suits. (Nixon famously wore polished black leather shoes for a photocall on a beach, and was mocked for wearing trousers that were slightly too short.)

Like Trump, he often defied conventional categories of left and right: it was Nixon, a Republican, who brought in price and wage controls, flew to Beijing and Moscow to shake hands with the communists and even called for a guaranteed minimum income. Above all, Nixon had an uncanny ability to tap the aspirations and anxieties of ordinary Americans — the kind of people who didn’t follow the news, weren’t interested in the minutiae of Washington politics and felt patronised by their richer and better-educated fellow citizens.

As Nixon told the Republican convention in 1968, he wanted to be the “voice of the great majority of Americans, the forgotten Americans — the non-shouters, the non-demonstrators. They are not racists or sick. They are not guilty of the crime that plagues the land … They are good people, they are decent people. They work and they save and they pay their taxes, and they care.” His critics gagged. But it worked.

Even Ronald Reagan, an incorruptible hero for Republicans who believe that Trump has infiltrated and perverted their party, was more like him than is often thought. In an excellent new biography, the former conservative commentator Max Boot, now an outspoken “Never Trumper”, points out that like Trump Reagan was a showbusiness creation, first as a radio sports presenter, then as a Hollywood actor and finally as a well-paid television ambassador for General Electric.

He was a fabulist, a storyteller seduced by his own fictions. (“He makes things up and believes them,” one of his children said.) His aides implored him not to trust the anecdotes he had seen in his favourite right-wing magazines. But even after learning that they were false, he repeated them anyway.

Metaphorical truth, Reagan thought, was more important than factual accuracy. At his inauguration in 1981, he looked out towards Arlington Cemetery and told a story about a GI called Martin Treptow, killed in the First World War, whose body had been found with a diary containing a moving patriotic pledge. In reality, Treptow wasn’t buried at Arlington, so Reagan’s speechwriters advised him to cut the story completely. But he refused. Like Trump, he knew the value of a memorable story — even if it wasn’t true.

Of course there are profound differences. Nixon was a thinker, a reader who dreamt of becoming an American Disraeli. Reagan was an optimist, a fundamentally sunny man who liked to be liked. Above all, both men were staunch internationalists, unwaveringly committed to the Atlantic alliance that held the line against communism in the Cold War.

In this respect, however, Trump stands in a very different tradition — the isolationist tradition that dates back to the earliest days of the republic but reached its peak with the America First movement in the 1930s. No wonder, then, that his country’s allies in Ukraine and Taiwan are watching his return so nervously.

Here, surely, is the arena in which Trump’s victory could most obviously make an epoch-shaping difference. Isolationist appeasement of Putin in Ukraine, and potentially of Xi Jinping in the South China Sea, would shatter the security architecture on which the western democratic world has depended since the Second World War. If Britain and other European countries are not already thinking seriously about increasing defence spending, they should be. For decades, self-styled peace campaigners have dreamt of a world without the heavy hand of American power. They may end up regretting that the American electorate gave them what they wished for.

What of the US itself? It’s possible, of course, that Trump’s victory marks a descent into a dark age of authoritarian oligarchy. To me, at least, it is strange and alarming that so many intelligent people make excuses for his shambolic failures of governance, his crude and incendiary rhetoric, his flagrant contempt for the everyday decencies we expect of our own colleagues and friends. But a new Hitler? Surely not.

Thanks to the federal system, presidential power is more limited than we often imagine. You don’t have to own a crystal ball to predict that scandals will soon eat into his political capital, which is limited anyway because he cannot run again in 2028. And it’s worth remembering that as devastating as this result was for the Democrats, the margins in the swing states really were not that great. In US presidential politics, a good candidate can make up for a multitude of sins. And since Harris won almost 48 per cent of the vote after a campaign of just 107 days, a more effective candidate could plausibly hope to do a lot better.

All the same, it’s surely time for commentators to accept that the world of the 1990s, let alone the world of the 1950s, is gone for good. The anger and anxiety of so many working-class voters, whose jobs and communities have been ravaged by globalisation and deindustrialisation, have become permanent features of our political landscape, not just in the US but around the western world. Populism will never go away; it has been present in democratic politics for as long as democratic politics has existed, and has become the defining idiom of our age.

As for the culture wars deplored by bien-pensant commentators, who see them merely as a cynical trap laid for empty-headed voters, they are not distractions from politics but the very essence of it. As Trump instinctively recognised, millions of people genuinely care about the demonstrations blighting university campuses or the lessons on sex and gender being taught to their children.

These issues are not confections, somehow imposed by “culture warriors” on the brainwashed masses. They are real issues born out of ordinary people’s everyday experiences. Indeed, for many voters they matter every bit as much as disappearing jobs or high prices. Who are we to tell them they are wrong?

The greatest lesson of Trump’s re-election, though, is very simple. It is high time we stopped treating him as a freak, an aberration, unique and un-American. He is the heir to a long tradition, and whether you like him or loathe him, his politics have become an indelible feature of the 21st century. Four years from now, Trump will be on his way out. What he represents, however, is not going away.

***

Source:

- Dominic Sandbrook, Aberration? Far from it. Trump has deep roots in America’s past, The Times, 9 November 2024. Also America in ’68: George Wallace, The First Donald Trump, The Rest Is History, 7 November 2024

***

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing

About the dark times.

— Bertolt Brecht

***