The Tower of Reading

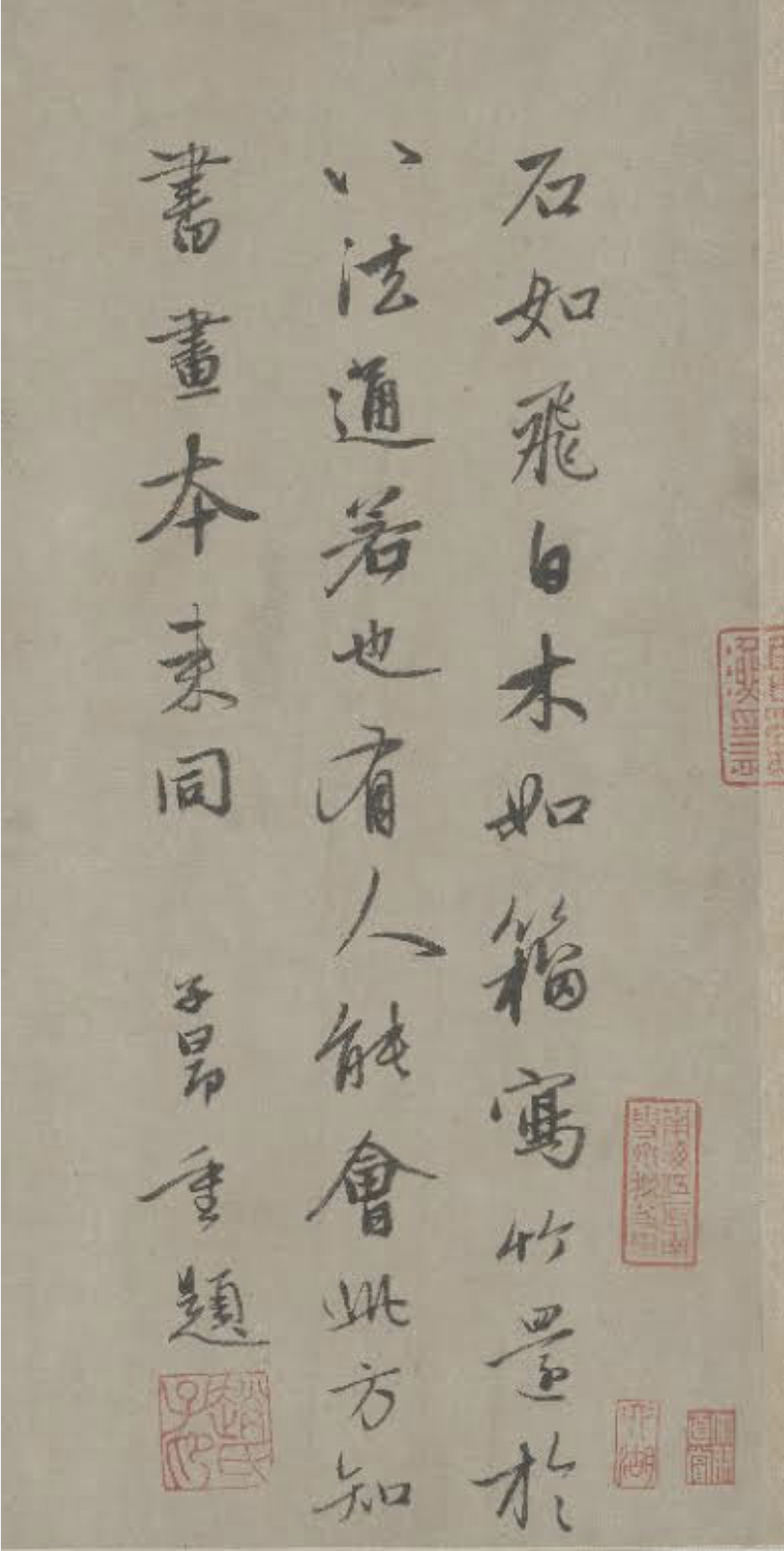

石如飛白木如籀

The 10th of October Festival 雙十節, also known as Double Tenth or Double Ten Day, commemorates the start of the Wuchang Uprising of 10 October 1911 which led to the fall of the Qing dynasty and the founding of the Republic of China in 1912. It is celebrated on Taiwan as National Day 國慶日.

A seismic transformation of Chinese culture was well underway in the decades leading up to 1912, it reached epochal dimensions in the years that followed and would continue up to and beyond the end of the century. Despite what appears to be a state of relative stasis today, that ‘transvaluation of all values’ continues to unfold along both overt and covert pathways.

On the eve of 10 October 2023, China’s party-state enshrined ‘Xi Jinping’s Cultural Thought’ 習近平文化思想 as the lodestar of artistic creativity in the People’s Republic. If nothing else, this dictator-centric flourish will justify ongoing expenditure on cultural ventures, many of which would be impossible under a regime merely fixated on the bottom line.

During the late-Mao era, the denunciation of Lin Biao and Confucius 批林批孔, as well as the nationwide reassessment of the dynastic-era novel Water Margin 水滸傳, necessitated the reprinting of long-banned works of classical literature and thought. The resulting politically driven cultural boom ended up having an unexpected impact on the artistic revival and creativity of the 1980s. Similarly, the cultural munificence of the Xi-era, known as ‘cash splashes’ 撒幣, a derogatory short-hand (撒幣=傻屄), contributes in a myriad of ways to the ongoing and unpredictable efflorescence of what we call The Other China.

[Note: For more on Xi’s ‘thoughts on culture’, see 劃地為牢 — A Cathedral of Pretence in the Pusillanimous Heart of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 13 October 2023.]

For an example of a ‘splash’, see the following introduction to the Pavilion of Nurtured Writing 文潤閣, the Hangzhou branch of China’s magnificent National Literary Repository 國家版本舘, designed by Wang Shu (王澍, 1963-):

[Note: See also 「一總三分」 總書記親自批准的這個項目有何特別之處?,央視網,2023年6月4.]

***

China Heritage marked the Mid-Autumn and National Day holiday season of 2023, officially dubbed ‘the dual festivities’ 雙節, with an essay from The Tower of Reading 唸樓 translated by Duncan Campbell (see The Same Fair Moon 千里共嬋娟, 29 September 2023). We will continue to publish a series of similar notes in the lead up to the official launch of The Tower of Reading, a project devoted to the work of Zhong Shuhe (鍾叔河, 1931-), writer, editor, publisher and an old friend. That project focusses on Shuhe’s collection 念樓學短 — ‘Studying Short Works of Classical Chinese Prose Selected in the Tower of Reading’.

The Tower of Reading is a section in China Heritage that doubles as a primer for New Sinology and complements our work on The Other China. ‘Rocks like flying white, trees like seal script’ is a preamble to that venture.

***

In keeping with our interest in the practice of démarquage — assemblage, purposeful plagiarism, borrowings, homages, references and quotations — we quote from Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill by Jason Farago, a critic at large for The New York Times. In it, the author refers to the inspired ‘imitative creativity’ of Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫, 1254-1322) of the Yuan dynasty. We believe that his observations are relevant to our own consideration of ‘intersections with eternity’, the theme of The Tower of Reading. I am grateful to Lois Conner for bringing this essay to my attention and to Annie Ren 任路漫 for locating the Wang Shu video.

On this day, we also remember Lee Yee, who passed away on 5 October 2022 (see ‘For’ برای — in Memory of Lee Yee, 5 October 2022).

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 October 2023

***

The Double Tenth in China Heritage:

- Audrey Tang 唐鳳 et al, Audrey Tang, Double Ten Day & The Transcultural Republic of Citizens, 10 October 2020

- Dai Qing 戴晴 et al, Commemorating a Different Centenary — Dai Qing on the 1911 Revolution, 12 October 2021

- From One to Ten and Back Again — 10 October 2022, 10 October 2022, Appendix XVIII 雙十 in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Further Reading:

- Pierre Ryckmans, The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past, China Heritage Quarterly, no. 14 (June 2008)

- Readings in New Sinology, China Heritage, 2017-

- 「一總三分」 總書記親自批准的這個項目有何特別之處?,央視網,2023年6月4日

***

Rocks like flying white, trees like seal script

Jason Farago

There is no inherent reason — no reason; this point needs to be clear — that a recession of novelty has to mean a recession of cultural worth. On the contrary, non-novel excellence has been the state of things for a vast majority of art history. Roman art and literature provides a centuries-long tradition of emulation, appropriating and adapting Greek, Etruscan and on occasion Asian examples into a culture in which the idea of copying was alien. Medieval icons were never understood to be “of their time,” but looked back to the time of the Incarnation, forward to eternity or out of time entirely into a realm beyond human life. Even beyond the halfway point of the last millennium, European artists regularly emended, updated or substituted pre-existing artworks at will, integrating present and past into a more spiritually efficacious whole.

Consider also the long and bountiful history of Chinese painting, in which, from the 13th century to the early 20th, scholar-artists frequently demonstrated their erudition by painting in explicit homage to masters from the past. For these literati painters, what mattered more than technical skill or aesthetic progression was an artist’s spontaneous creativity as channeled through previous masterpieces. There’s a painting I love in the Palace Museum in Beijing by Zhao Mengfu, a prince and scholar working during the Yuan dynasty, that dates to around 1310 but incorporates styles from several other periods. Spartan trees, whose branches hook like crab claws, derive from Song examples a few centuries earlier. A clump of bamboo in the corner coheres through strict, tight brushwork pioneered by the Han dynasty a thousand years before. Alongside the trees and rocks the artist added an inscription:

The rocks are like flying-white, the trees are like seal script,

The writing of bamboo draws upon the bafen method.

Only when one masters this secret

Will he understand that calligraphy and painting have always been one.

In other words: Use one style of brushwork for one element, another for another, just as a calligrapher uses different styles for different purposes. But beyond the simple equation of writing and painting, Zhao was doing something much more important: He was sublimating styles, some from the recent past and some of great antiquity, into a series of recombinatory elements that an artist of his time could deploy in concert. The literati painters learned from the old masters (important during the Yuan dynasty, to safeguard the place of Han culture under Mongol rule), but theirs was no simple classicism. It was a practice of aesthetic self-fulfillment that channeled itself through pre-existing gestures. Without ever worrying about novelty, you could still speak directly to your time. You could express your tenderest feelings, or face up to the upheavals of your age, in the overlapping styles of artists long dead.

Someone foresaw, profoundly, that this century was going to require something similar: that when forward motion became impossible, ambitious culture was going to have to take another shape. …

— from Jason Farago, Why Culture Has Come to a Standstill, The New York Times, 10 October 2023

***