Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XXXVIII

白茫茫大地真乾淨

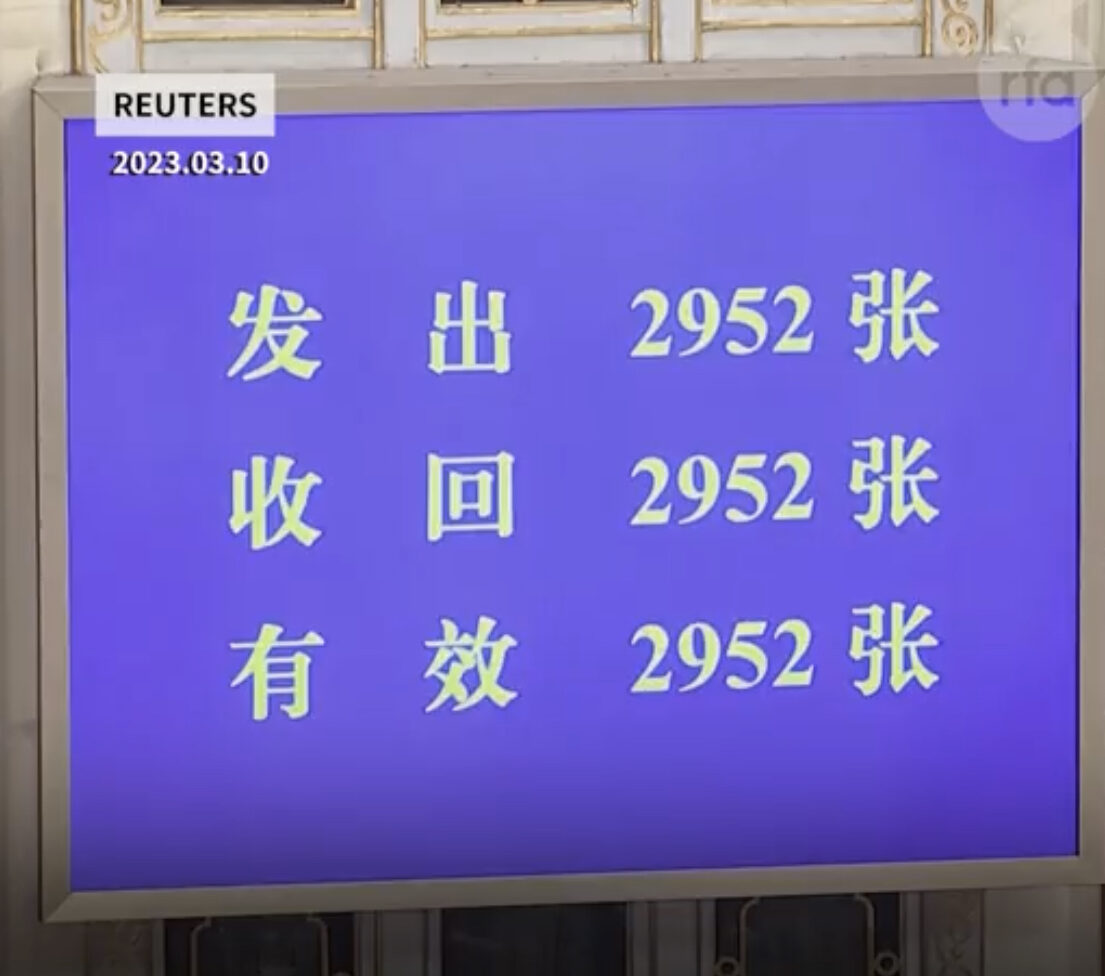

On 10 March 2023, the 2,952 delegates attending the first session of the Fourteenth National People’s Congress in Beijing voted unanimously to endorse Xi Jinping candidature to be China’s president for a third time. The Communist Party General Secretary and regnant head of government stood unopposed and even voted for himself.

***

***

The political theatre of the occasion, which China’s state media celebrated without irony as a model of the country’s ‘comprehensive people’s democratic processes’ 全過程人民民主, had its origins five years earlier when, on 11 March 2018, 2,958 of the 2,964 delegates attending the first session of the Thirteenth National People’s Congress voted in favour of twenty-one proposed changes to China’s Constitution, the most crucial one which, having done away with the previous term limits imposed on ambitious political leaders, potentially made way for what, at the time, we called Xi Jinping’s ‘terminal tenure’ as the leader of the country’s party-state-army.

A People’s Daily editorial titled A Powerful Constitutional Guarantee for the National Renaissance 為民族復興提供有力憲法保障 published on the same day as vote in March 2018 praised the peerless wisdom of the national legislature. In the elementary school style of literary Chinese deployed to demonstrate the cultural fluency of Party propagandists, the editorial declaimed:

Good governance is realised when laws are in step with the age; great can be the achievements when governance is consonant with the temper of the times. 法與時轉則治,治與世宜則有功。

The success of the constitutional change was introduced with a long-winded flourish that read:

The Nine Tripods [that in mythological times symbolised the unity of the state] can only be forged with tireless perseverance. The First Session of the Thirteenth National People’s Congress has voted to revise the Constitution. It is a decision that accords with the current of the times; it reflects a necessity at the heart of our enterprise; it is in accord with the wishes of the whole party and all the people of China; it is a step of enormous significance taken to advance the policy of achieving 360-degree legal governance in China, as well as being of enormous significance in advancing the modernisation of our governance structures and capabilities. This is a decision that also has a profound meaning for the continued pursuance and evolution of constitutional governance in the New Epoch of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. It is a decision of major significance for our present moment as well as having profound historical ramifications. As such it provides a powerful constitutional guarantee as we strive to fulfill the Dual Centennial Goals [of 2021 and 2049] on the path to realising the China Dream of Momentous National Renaissance.

九鼎重器,百鍊乃成。第十三屆全國人民代表大會第一次會議,表決通過了憲法修正案。這是時代大勢所趨、事業發展所需、黨心民心所向,是推進全面依法治國、推進國家治理體系和治理能力現代化的重大舉措,對更好發揮憲法在新時代堅持和發展中國特色社會主義中的重大作用,為實現「兩個一百年」奮鬥目標和中華民族偉大復興的中國夢提供有力憲法保障,具有重大現實意義和深遠歷史意義。

In an essay on the constitutional vote in Beijing, the independent Hong Kong commentator Lee Yee 李怡 observed that, as usual, Mainland Netizens had the measure of their leaders. Some quoted Stalin’s famous dictum about Communist Party led democracy:

Those who vote decide nothing; those who count the vote decide everything.

***

In the Xi era — one that I have frequently described as one in which there is more cult than personality — there is no dearth of full-throated and lusty expressions of hagiographic excess for the Leader. Although, for the moment, no one has claimed that Xi Thought radiates universal effulgence, or that it is a spiritual atom bomb, as was the case in the Mao era, it is early days and party flunkies like Li Hongzhong 李鴻忠, Party Secretary of Tianjin and a member of the Party’s Central Committee, show that there will be those who are up to the task. In October 2016, Li proved himself to be ahead of the laudatory curve when he formulated a palindrome-like slogan:

忠誠不絕對就是絕對不忠誠。

If you’re not absolutely loyal, you’re absolutely not loyal.

— from 李鴻忠,忠誠不絕對就是絕對不忠誠 以「無我」示忠, 2016年10月22日

We are pleased to report that on 10 March 2023, Li Hongzhong’s devotion was duly rewarded when he became the first-ranking Vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Li garnered 2950 votes; one nay and one abstention constituted the feeblest of feeble ‘protest votes’.

***

In March 2014, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un was elected to the rubber-stamp parliament with 100% votes. ‘He’s not the only leader to win an election overwhelmingly,’ wrote Tanvi Misra:

Iraq’s former president Saddam Hussein also won 100% votes in a 2002 referendum on whether his decades-long rule was to continue. Former Supreme Leader Kim Jong-il fared almost as well as his son in 2009, winning 99.9 % of votes. Raul Castro earned 99.4% votes in the 2008 Cuban election and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad secured 97.6% votes for his 2007 presidential referendum.

Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov in 1992 and Chechnya’s United Russian Party in 2011 both secured 99.5%. Kurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, also from Turkmenistan, topped them with 97% in 2012. In 2004, Georgia’s Mikheil Saakashvili won more than 96% votes after his predecessor was ousted in a bloodless revolution.

In March 2023, China’s Xi Jinping joined this illustrious company.

***

In our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium we mark the end of a decade-long process culminating in Xi Jinping becoming China’s new, undisputed and unopposed leader for life.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 March 2023

***

‘China Decides’ 2023:

- 你儂我儂 ‘It’s all ruined by the politics’, 5 March 2023

- 萬變不離其宗 — The Harry Houdini of Marxist-Leninist regimes; the David Copperfield of Communism; the Criss Angel of autocracy, 6 March 2023

- 禽獸食祿 — Craven, Servile Knaves Hold Office, 7 March 2023

- 鴨架湯 — It’s Time for Another Serving of Peking Duck Soup, 12 March 2023

Related Material:

- A Hosanna for Chairman Mao & Canticles for Party General Secretary Xi, 22 October 2022

- Xi the Exterminator & the Perfection of Covid Wisdom, 1 September 2022

- The Curse of Great Leaders — the Xi Jinping decade and beyond, 20 July 2022

- The innocent cry to Heaven. The odour of such a state is felt on high., 1 October 2020

- The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud, 10 March 2020

- A People’s Banana Republic, 5 September 2018

- Who’s on First? — China’s Successive Failures, 20 November 2017

- The Ayes Have It, 18 October 2017

Sovereigns and subjects become intoxicated together at the cup of tyranny …. Tyranny is the handiwork of nations, not the masterpiece of a single man.

— Marquis de Custine

***

April 1969, March 2023

***

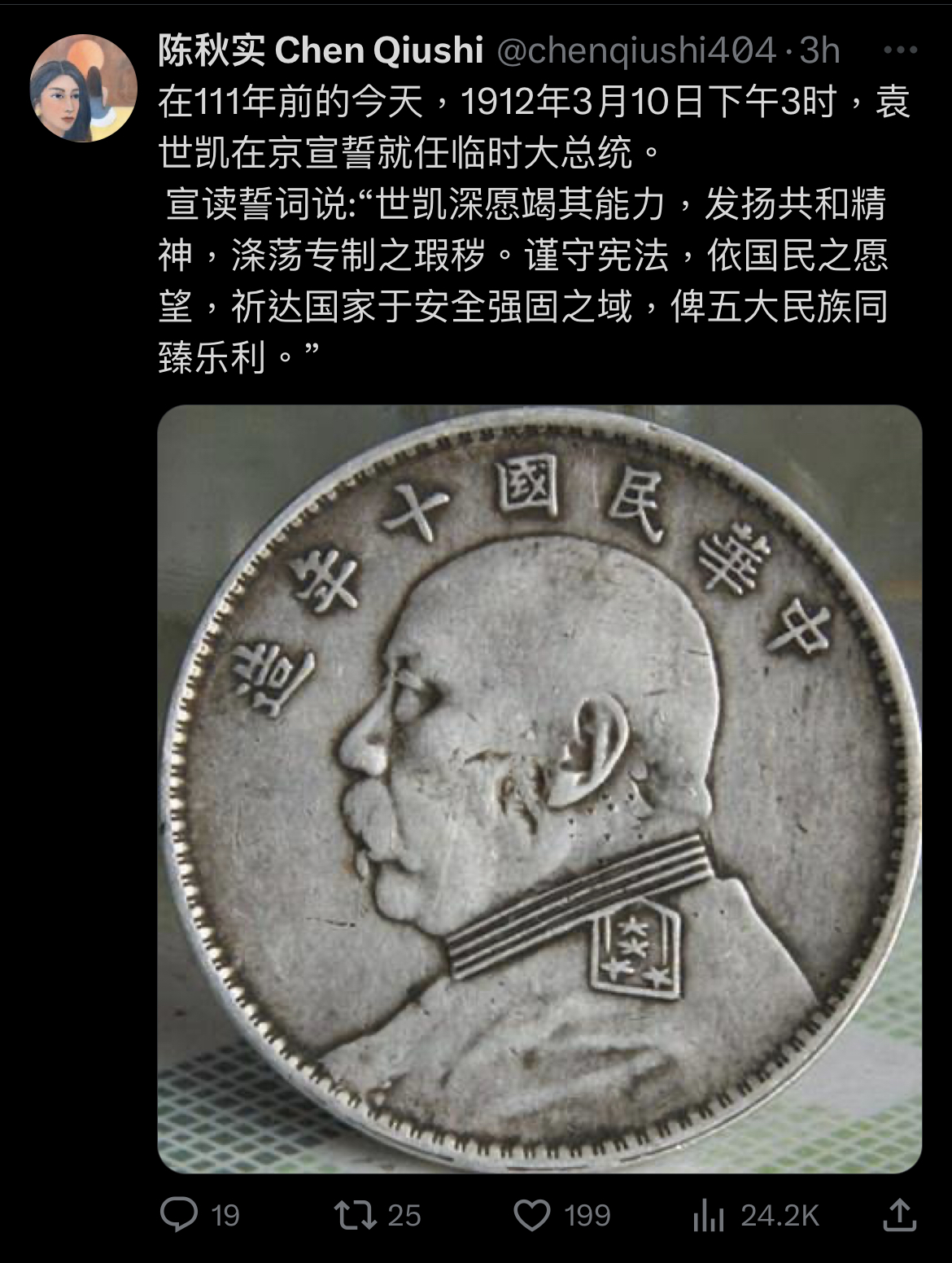

On 10 March 2023, the first day of the rest of Xi Jinping’s political life, Chinese commentators noted that it was exactly 111 years since Yuan Shikai began his term as president of the Republic of China.

However. as Zhang Lifan (章立凡, 1950-), a noted independent Beijing historian, Tweeted:

10 March 1912 was a moment when history moved forward; 10 March 2023 is a day on which history regressed. The former marked a serious drama worthy of the name; the latter is a farce.

第一個3月10日,是歷史的進步;第二個3月10日,是歷史的退步。第一個是正劇,第二個是鬧劇。

Back in the 1910s, however, it was not long before President Yuan’s rule also devolved into farce. In late 1915, he mounted the Dragon Throne in a short-lived attempt to restore the hereditary monarchy.

‘Yuan-Xi redux’ is now known as the ‘Secondary Yuan Paradox’ 二次元難題, a historically transparent two-dimensional dilemma.

***

***

Since the abdication of the last dynastic house in 1912, China’s imperial canker has never been entirely eliminated. Of course, in today’s People’s Republic the state media offers up convoluted folderol and mind-numbing detail regarding the collective and consultative nature of the country’s political system. The reality is that it is authoritarian in nature; national life is organised in keeping with a top-down Bolshevik Party structure while the authorities pursue a range of hyper modern techniques welded to various charismatic elements of late-traditional statecraft; government mechanisms are rigidly hierarchical; and comrade-citizen-consumers are viewed as productive assets, unless they become white-anting nay-sayers. In everyday attitudes towards power and privilege, along with an official and private language that is steeped in un-democratic notions, an autocratic temper continues to suffuse the life of China’s party-state.

An overt embrace of the imperial era has been evident from the mid 1990s when, gradually, the Manchu-Qing dynasty — excoriated for most of the twentieth century as a non-Han, conquest dynasty that through political ineptitude and corruption had allowed Eternal China to fall prey to foreign imperialist aggression — was incorporated into the Official China Story, that is the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist historical narrative delineating China’s fall and revival. As the party-state formulated ways to talk about the future in the new millennium, it selectively embraced what is thought of as the country’s last Golden Age in the eighteenth century; among other things, it did so by launching well-funded cultural projects and employing such dynastic terms as the Prosperous Age 盛世 to depict its own achievements. In this and in a myriad of other ways, the authorities long ago alerted attentive students of the Chinese world to the importance of understanding the gravitational pull of the past.

In defense of the abolition of term limits on state leaders, that is, with the granting of what I call ‘terminal tenure’ to the Chinese leader Xi Jinping, energetically supported by the country’s sham institutions of democracy, propagandists have energetically celebrated what is in effect a reactionary move as ‘political innovation’, what they hail as part of New Style Party Politics 新型政黨制度. Reaction masquerades as reform; the dangers of the past are repackaged as the hope for a sustainable future. China’s propagandists attempt thereby to nullify the claims of western liberal democracies that they alone offer an equitable, self-correcting system that, for all of its faults, can best fulfill the needs and realise the aspirations of modern humanity.

***

In March 2018, when China’s national legislative body voted to reinstate one-man rule, we selected three recent commentaries from ‘Ways of the World’ 世道人生 column written by the celebrated journalist Lee Yee 李怡 (李秉堯). They dealt with the political drama unfolding in contemporary China, including Lee Yee’s reflections on the sombre fate of democracy in the Communist-controlled territory of Hong Kong.

In the first essay — which took as its theme the Doppelgänger Yuan Shikai/ Xi Jinping — Lee Yee quoted the expression ‘the landscape desolate and bare’ 白茫茫大地真乾淨 from the famous eighteenth-century novel The Dream of the Red Mansion (紅樓夢, also known as The Story of the Stone 石頭記). That expression appears in ‘The Birds Into The Wood Have Flown’ 飛鳥個投林, an epilogue to a series of twelve verses which contain clues about the fate of key characters in the story.

Like birds who, having fled, to the woods repair,

They leave the landscape desolate and bare.

好一似食盡鳥投林,

落了片白茫茫大地真乾淨。

Lee Yee’s second reference to The Dream — ‘truth becomes fiction when the fiction’s true’ 假作真時真亦假 — recalled the famous couplet:

Truth becomes fiction when the fiction’s true;

Real becomes not-real when the unreal’s real.

假作真時真亦假

無為有處有還無

— The Story of the Stone, Volume I: The Golden Days,

石頭記, trans. David Hawkes, p.55

***

In his biography of Yuan Shikai, Jerome Ch’en notes that the first president of the Republic of China:

assured the nation of his lack of interest in personal power, for “an on old man of sixty has no ambition”. He was actually fifty-three… . His instructions to the Political Council clearly stated that the strength of a nation had nothing to do with whether the nation was a monarchy or a democracy. He was more interested in national strength than in republicanism. …

On August 18 [1913], the Council of State endorsed a suggestion that the presidential election law be amended; the Constitutional Compact Conference did so on December 28. Under the new law, the president’s term of office was extended from five to ten years, with no limit on the number of terms. If the Council of State deemed it necessary, the president could even stay in office without going through the procedure of an election.

— Jerome Ch’en, Yuan Shih-k’ai,

Stanford University Press, 1972, p.164

— from Lee Yee, A Landscape Desolate and Bare (The Best China X), China Heritage, 12 March 2018

Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué

Xu Zhangrun

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

In March 2018, the Chinese legislature approved revisions to the constitution that effectively put an end to the already minimal political advances achieved following the economic reform policies originally introduced by the Communist Party in late 1978. Although the revisions [which abolished term limits on national leaders, making it possible for President Xi Jinping to stay in power indefinitely] unsettled China’s legal world, the outrage was expressed sotto voce; the disquiet barely went beyond what in the Soviet Union used to be called “kitchen table talk.”

Meanwhile, in public, a host of obsequious legal scholars vied to offer fawning praise for the new dispensation. Seemingly unabashed as they betrayed previous held views, they gave no hint of any internal moral struggles or sense of ambivalence about their conversion. Quite the opposite: many appeared to relish the fact that they were able to navigate the situation so adroitly. Instead, they focused their energies on how they could best realign themselves and pursue professional advancement.

At this crucial juncture, China’s political, business, and academic elites revealed a core of craven self-interest and vacuous hypocrisy. The display was even further evidence of the degraded state of our nation’s public life, one that has long been characterized by brazen political opportunism, systemic corruption, and the celebration of populist thuggery.

Various edicts were issued from on high that banned all public discussion, let alone disapproval, of the constitutional changes. The authorities made it quite clear that dissent would be severely punished. In particular, legal scholars were cautioned to keep their own counsel.

At the time these changes were being proposed, I bumped into a colleague from Tsinghua University who had long enjoyed a seat on the National People’s Congress [the legislative body that would soon rubber-stamp the constitutional reforms]. He was quick to tell me that he, too, was outraged by the mooted changes. They were, he assured me, indeed absurd, an egregious act of revanchism. In the same breath, he said: “But I’m just letting off steam. Of course, when the time comes to vote, I’ll be raising my hand along with everyone else. No one is crazy enough to paint a target on their back.”

His attitude was evidently shared by a majority of the men and women who had a substantive say in the matter [with the revision passing by 2,958 votes to two]. Fear drove them to come up with various rationalizations for their actions, and so our country is now under the sway of a Great Reversal. This came to pass not in stealth, but openly and with the acquiescence and complicity of China’s intelligentsia. Their stance has proved to be little different from that of the imperial slave-subjects of yesteryear; it has hastened China’s lurch back into the familiar old rut of totalitarianism. What has all of this wrought? It is more than evident: we now live in a nation beset by mounting domestic and external challenges.

I believe that legal scholars like me are akin to a priesthood that serves natural law, rather than merely justifying the requirements of the state. We should be the guardians of a system of justice based on due process, one that ensures equality before the law; a system that is underpinned by the conviction that all citizens can and should feel secure in an environment of unthreatened coexistence. That is why, in 2018, I decided that to remain silent at such a critical moment would be a betrayal of my life’s work. If even people like me shied from speaking out at such a time, what hope was there for Chinese society?

My belief that it was incumbent upon educators like me to give voice to their indignation and concern publicly led me to write “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes,” an in-depth analysis and critique of the state of modern China. It was in a mood of immense relief that I published it online in late July 2018; I had acted out of a duty to speak up and my hope was that my words would reach as wide an audience as possible. I even dared to think that what I had said might embolden others to raise their voices.

“Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes” was a warning to my compatriots, alerting them to things that were happening right here and now. It was an appeal calling on people to protect China’s reforms—hard-won advances derived from the immense sacrifices that countless numbers of our fellow citizens had made over four decades. It was also an exhortation to people to do what they could to prevent China’s further backward slide, one that I believe might all too easily lead to a new civil war. My admonition was also born of the anxiety that China could yet again find itself isolated by the international community.

Naturally, my essay was an open challenge to the powers-that-be, and I knew full well that by publishing it, I was courting disaster. Yet I was at peace with myself, and awaited with equanimity what fate had in store for me. As expected, the punishments rained down on me with increasing severity until, in the summer of 2020, the authorities finally bared their teeth.

They resorted to the tried-and-true methods of the proletarian dictatorship: they destroyed my livelihood and they incarcerated me. They hoped to repress my heresy by crushing my spirit. The only thing that they have managed to do, however, is to turn me into a semi-exile under partial house arrest in my own land. I was mentally prepared for all of this, and all that I had expected has duly been visited upon me. I regret nothing.

What does dismay me, however, is that since I published “Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes,” everything I feared might happen has come to pass, and new evidence in support of my case emerges every day. The “Eight Fears” that I identified in July 2018 are now a reality. In the space of three short years, particularly after the Covid-19 pandemic, the totalitarian tendencies of the Chinese party-state have become more evident. What was already an obnoxious oligarchy has now been replaced by a Chinese version of the Führerprinzip, along with a brutal form of purge politics based on the Leninist-Maoist model.

Populist statism and institutional statism have become intertwined and now aid and abet what I have previously called “Big Data Totalitarianism.” In tandem with this, mainstream global politics have undergone profound changes in recent years. On the international stage, the politics of the “war on terror” is giving way to a new anti-Communist animus aimed at China. Previously, the People’s Republic enjoyed a collaborative and relatively harmonious relationship with the international community. That has seen a sea change as many nations have radically revised their views of our country and the direction it is taking. By generating imaginary enemies in all quarters, China is further isolating itself, even if the vast scale of the People’s Republic will ensure its continued international influence, at least for the time being. …

I have often referred to China’s party-state governance model as “Legalist-Fascist-Stalinism.” The rulers overwhelmingly concentrate on what are traditionally called the “Rivers and Mountains”; this [imperial concept] is their patria. When confronted by such questions as “What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you use it? To whom are you accountable? And how do we get rid of you?” the Chinese system is struck dumb, unable to respond.

More to the point, it is a system completely lacking the kind of democratic processes that can ensure a peaceful transfer of power. Without a stable political process of succession, the fate of the nation ultimately relies on armed might and coercion. In the final analysis, the authoritarian party-state system stands in stark opposition to historical progress, to human love, and to normal political life. That is why, to this day, it enjoys no real popular appeal.

Above, I observed that China has lurched back into “the familiar old rut of totalitarianism.” Despite appearances, the Communist Party has never veered far from that path. Its fundamental nature has remained unchanged and, whenever it has weathered a crisis, the Party merely redoubles its efforts. Whatever it may achieve is always hamstrung by the energy it puts into denying all other political possibilities and by its dogged refusal to evolve. The obdurate pursuit of power and the insatiable appetite for self-approval have created a system that, at its heart, is paranoid and brittle. By treating the people as nothing more than objects that demand a constant regime of stability maintenance, or even as enemies that must be corralled, it further drives itself into a cul-de-sac.

For well over a decade, China has seen an ostentatious kind of performance that I think of as “The Politics of the Successor Playboys.” It has been dominated by two scions of the Party nobility.First [during the ascendancy of Bo Xilai], there was a parade of comely policewomen in the cities of Dalian and in Chongqing, as well as the “Red Songs and Black Attack” movement [a neo-Maoist campaign supported by Bo, active from 2009 to 2012]. For his part, Xi Jinping has devoted considerable energy to pursuing vanity projects, like his so-called toilet revolution [to improve public bathrooms], and launching a series of policies aimed at cleaning up the country’s urban aesthetics. These include a concerted effort to demolish unsightly buildings and force low-income residents out of prime city real estate, and a raft of regulations aimed at standardizing shop signs and eliminating displeasing overhead wires and cables. Even the dead have not been spared his zeal, and farmers are now forbidden to exercise the traditional practice of burying deceased family members on their own land. So strictly do local officials enforce this ban that they seize and burn handcrafted coffins.

Then there is all the hue and cry about the “One Belt, One Road” initiative and the much-vaunted policy of eliminating extreme poverty, something that was supposedly carried out according to a predetermined timetable. All of these appear, superficially at least, to be major achievements that reflect a purportedly daring political vision. In reality, they are symptomatic of a particular brand of political willfulness; they are a modern-day version of Mao’s revolutionary romanticism. More than anything, they are smug displays of delusional hubris.

As ever-new projects and vanity policies are pursued with immoderate enthusiasm, we are actually witnessing the handiwork of an autocratic roué. The accumulated political, social, and economic bounty that was painstakingly acquired since 1978, one that carried in its wake the promise of a modicum of political evolution, has been squandered. Now we are seeing the reckless depletion of the remaining reserves of China’s reform era.

This is further proof that for a nation to play a meaningful part in the modern international world, it is insufficient to revel in possessing an almighty state with limitless political power. What is necessary is the building of a civilized society and a political system that is underpinned by a meaningful culture of law. There is no escaping the fact that nations need a form of politics grounded in a constitutional order. By that, I mean a modern constitutional framework that protects the freedom and human rights of its citizens. In the present era, this is still the best path for any truly rational society.

To advocate on behalf of such a system is not merely a self-serving and pragmatic response to historical inevitability; rather, if China is to hope for collective political salvation, it is a necessity. China and the Chinese people lack a truly resilient political system; we are instead burdened with one that, despite its formidable appearance, is inherently fragile. It is threatened to its core by every tempest.

Meanwhile, we must cope with our anxieties as best we can, holding on to what inspiration we can. Even as this age of darkness advances, I know that regardless of my benighted circumstances, my soul rises up, confident in humanity’s better future.

***

Source:

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué’, trans. G.R. Barmé, New York Review of Books, 9 August 2021

***

***

2,952 —

a Number to Remember

***

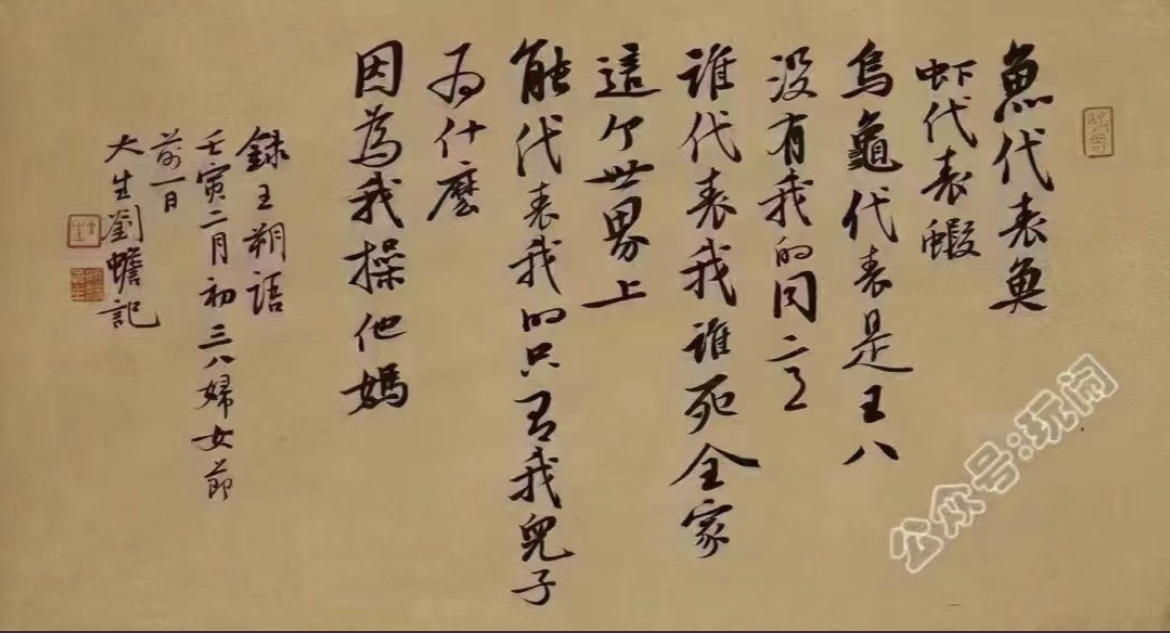

魚代表魚,蝦代表蝦,烏龜代表是王八,沒有我的同意,誰代表我誰死全家。 這個世界上,能代表我的,只有我兒子,為什麼? 因為我操他媽。