Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXXIII

唯物懟唯心

History is the most valuable guide we have to the behaviour of human beings in the present; but this is not because it offers neatly tailored lessons of the kind that Thucydides or Machiavelli were prone to celebrating. The true value of history is that it reminds us of how infinite are the ways to be human; of how utterly contingent are our own circumstances; of how inevitable it is that much of what we take for granted will be viewed by later ages and peoples as utterly bizarre. Try to make decisions in the consciousness that the assumptions governing them are largely the product, not of universal truths, but of the very opposite: a moment in time that will very soon have slipped into the past.

— Tom Holland, historian and podcaster, 4 December 2024

***

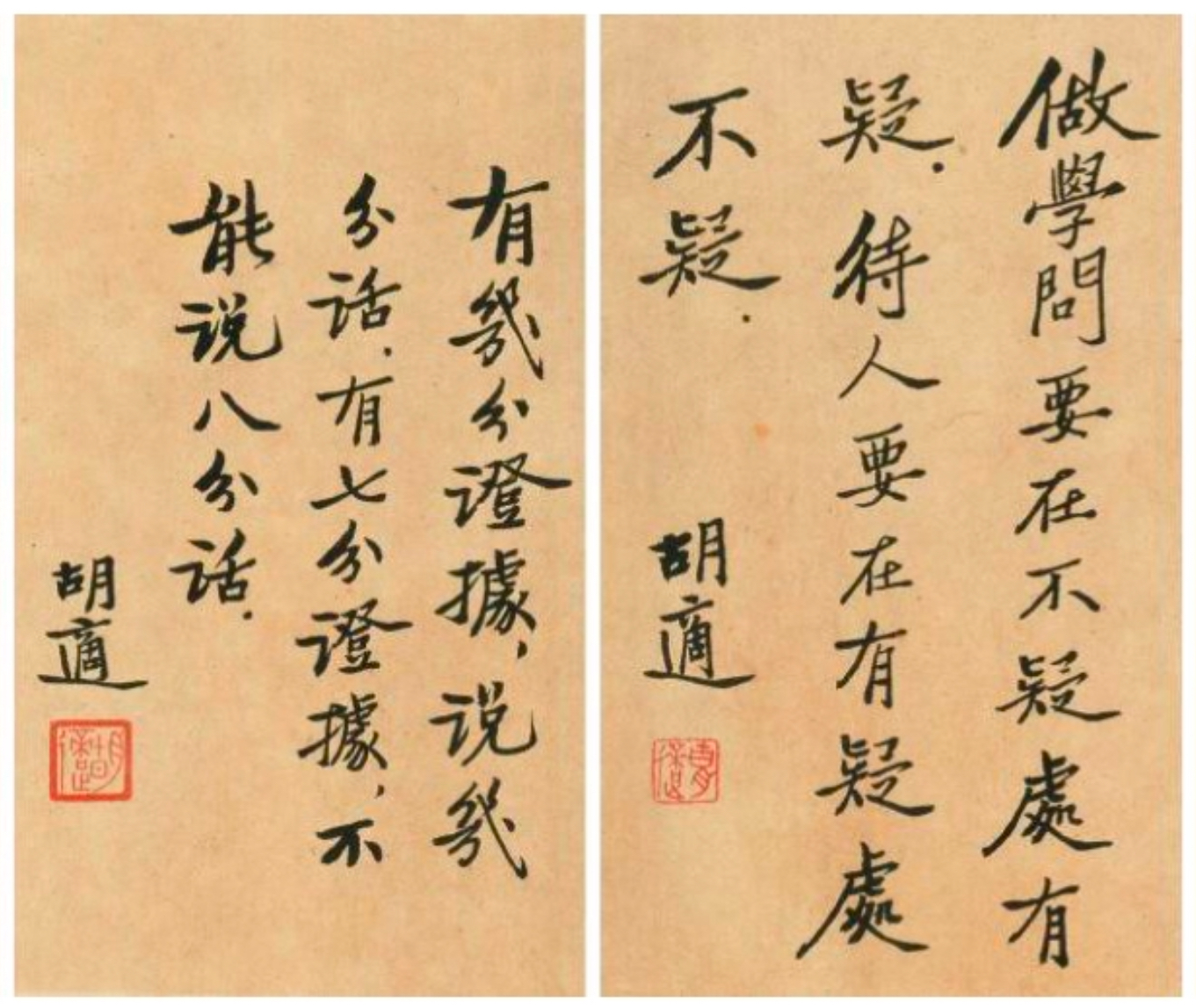

The year 2024 marks the centenary of what I think of as China’s ‘Dark Enlightenment’, an autocratic doppelgänger that is entwined with the May Fourth legacy of enlightenment, democracy and free thought. The end of the beginning of the Dark Enlightenment was marked, seventy years ago with a nationwide ideological attack on Hu Shih (胡適, 1891-1962), a leader of the May Fourth Enlightenment, and Mao Zedong’s ideological nemesis.

Hu Shih’s advocacy of liberal democracy, political gradualism, independent academic thought and moderation were anathema to China’s Stalin, as was his advocacy of wholesale Westernisation and his support for American liberal values. In 1949, Mao had named Hu Shih, along with the activists who supported a Third Way that promised to find a path between the clashing titans of the Nationalists and Communists, as agents of Western imperialism. Their ideas and political activism were a direct threat to the Communist cause (for details, see White Paper, Red Menace). Mao would charactise the political chasm between China’s liberals and his Marxist-Leninist illiberalism in philosophical terms as being a clash between ‘materialism and idealism’.

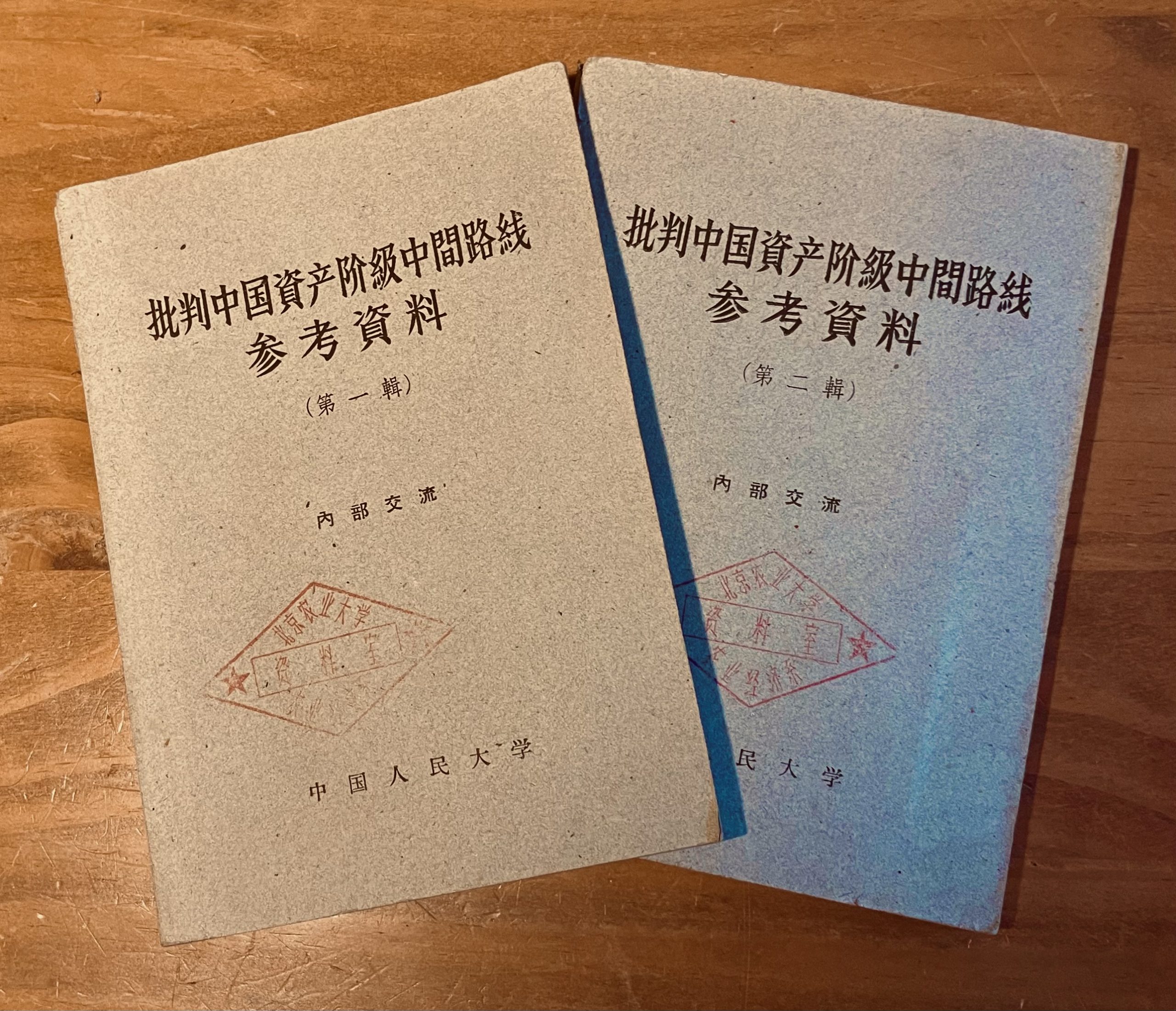

In 1954, a critique of ‘bourgeois-style’ scholarship related to the famous Qianlong-era novel The Dream of Red Mansions 紅樓夢 was used by Mao and the Party to denounce the May Fourth thinker and liberal democrat Hu Shih. (For a recent study of that purge, see Johannes Kaminski, Towards a Maoist Dream of the Red Chamber, Journal of Chinese Humanities, 3 (2017): 177-202.) More broadly, the ideological campaign, which involved countless meetings, speeches, declamations and criticisms, was aimed at eradicating Hu’s influence in academia, in particular Western scholastic approaches and standards, and imposing Marxist-Leninist methodology throughout the country’s tertiary institutions. The attacks on Hu Shih included an intensified negation of China’s modern liberal democratic tradition, a process that Mao had formally initiated in 1949 when he betrayed his non-Party supporters, as well as a rejection of ‘idealism’, a malleable term in the Communist lexicon capacious enough to include Western concepts related to abstract humanity, individual human worth and human rights. The materialist view of society, history, culture and life in general that was institutionalised by the Party in the early 1950s has formed the basis of the party-state and its propaganda ever since. Under Deng Xiaoping and his successors, despite their limited critique of the High Maoist era (c.1958-1976), the attack on Hu Shih was reaffirmed, even though some Chinese intellectuals subsequently cloaked their recuperation of liberal ideals through a seemingly objective historical study of Hu (see, for example, the material on the ’62 Scholars below).

Just as the independent-minded figures Wang Guowei and Chen Yinque are unrequited spirits at Tsinghua University, so Hu Shih’s shade as a paragon of scepticism and inquiry bedevils Peking University. (See The Two Scholars Who Haunt Tsinghua University.)

***

***

From the start, the Dark Enlightenment fed off the promise of progress, democracy and rationality during the New Culture Movement (1917-1927). It was further bolstered by the anxieties of the vast, displaced caste of Chinese post-imperial literati, as well as being energised by a coterie of ‘awakened youth’, young men and women who were both caught up in and agitators within the political maelstrom of the time.

Internecine strife, economic dislocation, imperialist aggression and a rising tide of sloganeering nationalism created a Dark Enlightenment that in turn informed the authoritarianism both of the Nationalist Party during its long era of political tutelage (訓政, c.1927-1988), first under Chiang Kai-shek and then his successor, and of the Communist Party which, from the 1930s, married a sinicised version of Stalinism to statist Confucianism.

China’s Dark Enlightenment is a multifaceted phenomenon. Today, recalling the 1954 attacks on Hu Shih, liberalism, critical thought and independent scholarship, I would highlight two other milestones in the post-Mao history of the closing of the Chinese mind, both of which are three decades apart:

- The 1984 attack on Marxist Humanism and Spiritual Pollution that reaffirmed the decades-long ideological struggle with the Enlightenment tradition and, for all intents and purposes, foreclosed substantive political reform thereafter (see Spiritual Pollution Forty Years On); and,

- Xi Jinping’s 2014 visit to Peking University, the former epicentre of the May Fourth Enlightenment, during which he extolled the Communist Party’s domination of Chinese academia, thought and aspirations (for details, see Homo Xinensis).

***

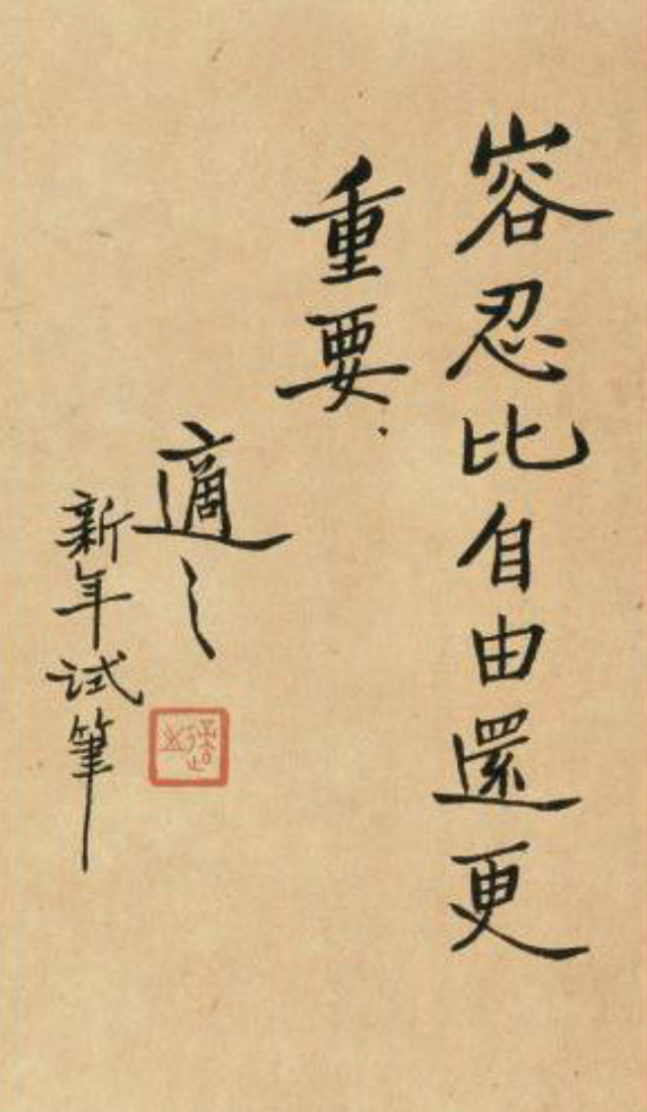

We have previously noted that Hu Shih, having made significant contributions to the liberal tradition of modern Chinese life in the 1920s and 1930s would, over time, find the gravitational pull of politics, power and prestige exerted by Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong’s political nemesis, and the Nationalist Party that he led, hard to resist. Hu followed the Republic of China to Taiwan whence it relocated following the bloody Nationalist Party bloody suppression of local Taiwanese on 28 February 1947 and defeat at the hands of the Communists on the mainland. Although the last decade of Hu’s life was crowned with honours it was also elegiac. As Chiang Kai-shek’s 諍臣 zhèngchén — ‘outspoken counsellor’, although the term can just as well mean ‘an autocrat’s intimate’ — Hu Shih gradually reduced his earlier lofty liberal aspirations to a wishy-washy maxim: ‘tolerance is more important than freedom’ 容忍比自由重要.

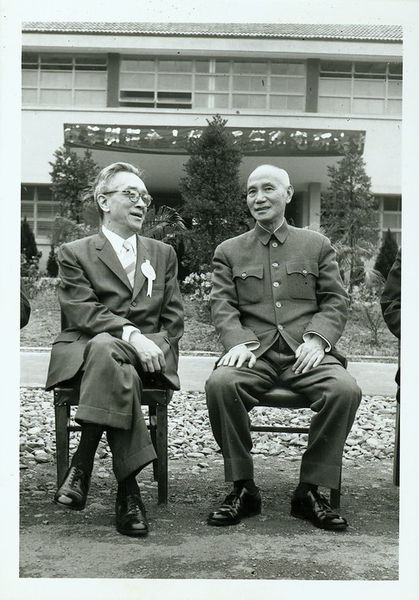

In his later years, Hu Shih’s once-spirited defence of independent political values and free speech faltered and then failed. Granted, there are reports that, in April 1958, he had the momentary temerity to disagree with Chiang publicly. It was on the occasion of the president-for-life’s visit to Academia Sinica, a prestigious institution of which Hu was president, at Nangang outside Taipei. Chiang made an observation that the liberalism promoted during the May Fourth era by people like Hu had directly contributed to the rise and eventual dominance of the Communists on the Mainland. Even though Hu’s protest was little more than a muffled ‘That’s not correct’. It was the last time that Chiang visited the Academy.

***

***

Shortly thereafter, in a pitiful denouement to a sometimes stellar career, Hu’s reputation as an exponent of democratic virtues was irrevocably tarnished as a result of the infamous Lei Chen Case 雷震事件 of 1960 which involved the banning of Free China 自由中國, a journal of independent opinion which published critiques of Chiang Kai-shek’s dictatorial government and advocated for both economic and political reform. Hu had been the chief executive of the journal although the editor-in-chief was Lei Chen 雷震. Lei, who was a former political adviser to Chiang Kai-shek, had become a prominent advocate of democracy and opposition politics, and he was a leading figure in the establishment of the China Democratic Party 中國民主黨. The philosopher and educator Yin Hai-kuang 殷海光 was also a frequent contributor to the editorial pages of Free China and his principled support for the new opposition party helped cement his reputation as the intellectual leader of liberalism on the island. Lei Chen was arrested, tried by a military tribunal and jailed for ten years. Yin was accused of ‘fomenting rebellion’ and silenced. Many others would be subjected to long years of political persecution. Following Lei Chen’s downfall, apart from impotent handwringing and counselling Chiang to exercise restraint, Hu maintained a studied distance from his erstwhile colleagues. His critics note that he even failed to muster sufficient courage to visit the imprisoned Lei, an old friend.

This final benighted chapter in the story of China’s most famous twentieth-century liberal is the theme of Confronting Autocracy — the contrasting attitudes of Hu Shih and Yin Hai-kuang 面對獨裁——胡適與殷海光的兩種態度 (Taipei: Yunchen Wenhua 允晨文化, 2017) by Chin Heng-wei 金恆煒, a noted Taiwanese political commentator, essayist and editor.

Taiwan eventually sloughed off the baleful legacy of China’s Dark Enlightenment, more as a result of the island’s indigenous political forces than its mainland occupiers. Meanwhile, the suppressed, revived and fractured liberal tradition on the Mainland remains in the thrall of the century long Dark Enlightenment. As we argued in Translatio imperii sinici, China’s modern ages of authoritarianism have come together under Xi Jinping. A few heroic — quixotic? — exemplars, including Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 and Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, both of whom feature in China Heritage, nonetheless bear witness to The Other China, as well as to the nobility of failure.

***

I arrived in Beijing as an exchange student in October 1974, exactly twenty years after Mao launched his purge of Hu Shih’s idealism. Having just turned twenty and with a birthday on 4 May, I was intrigued when we studied the movement as part of our education in High Maoist politics. Despite the dramatic changes of the post Mao decades, I remained mindful of the 1954 attack on humanism and the shadowy significance it has had ever since.

***

In 2009, I wrote about the light and dark anniversariese of modern China that were variously commemorated and elided during that year. Now, fifteen years later, we mark the seventieth anniversary of the denunciation of Hu Shih by reprinting Hu Shih: An Appreciation by Jerome B. Grieder, author of Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance: Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1937, which first appeared in The China Quarterly, and which I reprinted sixty years later, in 2012, in China Heritage Quarterly.

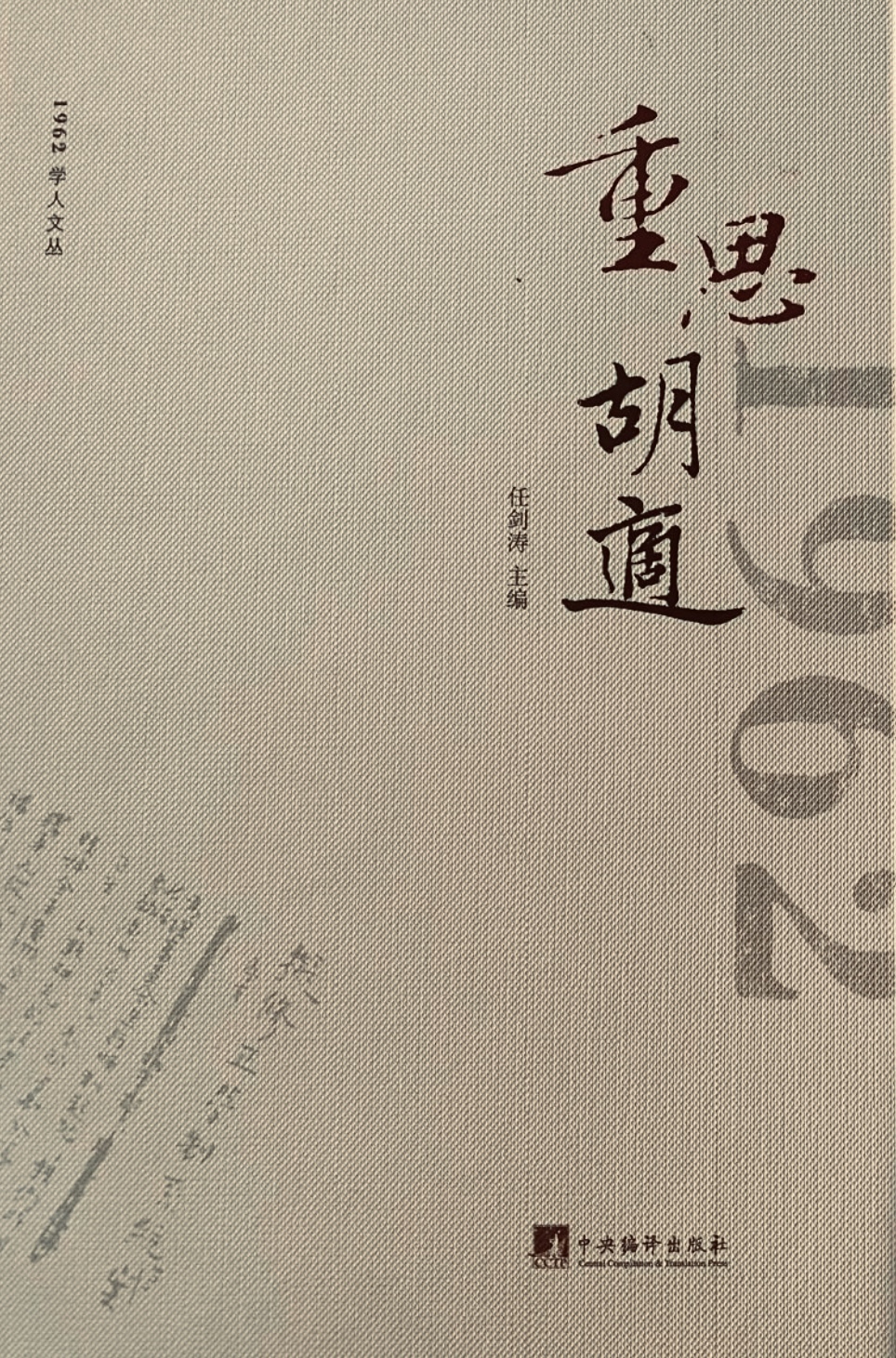

This is followed by the table of contents of Reconsidering Hu Shih 重思胡適, along with the introduction to that collection of essays by the ’62 Scholars — 1962年學人 — an informal group of predominantly Beijing-based academics who were all born in the year of Hu Shih’s death. Apart from their birth year, the group shared an interest in the tradition of Chinese liberalism and its contemporary significance. Following an initial gathering in 2012, on the cusp of what turned out to be the advent of Xi Jinping as party-state-army autarch, the ’62 Scholars published Reconsidering Hu Shih as the first volume in a planned series of books. A second volume, Rethinking the Nation-State 重思國家, appeared shortly before the group went into abeyance. Among the ’62 Scholars, Xu Zhangrun remains loyal to the group’s original vision as well as being defiantly active in the face of constant official pressure and harassment.

***

My thanks to Lois Conner for permission to use one of her recent works, to Reader #1 for pointing out various infelicities in the text and to Xu Zhangrun for introducing me to the ’62 Scholars and their denouement.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

30 December 2024

The day of a looming Black Moon

***

Further Reading:

- 許章潤、高全喜等,我們要借胡適來清理骨子裡的文革血液,共識網,2015年1月8日

- The China Critic, June/September 2012

- May Fourth at Ninety-nine, 4 May 2018

- Anniversaries New & Old in 2019 — Remembering 5.4, Accounting for 4.28, 4 May 2019

- Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Beijing, 8 May 2020

- Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Washington, 14 May 2020

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- Chapter Four 1984年 — Simon Leys on George Orwell in 1984, 20 June 2024; Part II, 義憤 ‘Profoundly indignant. Longstandingly indignant. Dignifiedly indignant.’, 28 June 2024

- Chapter Thirty-four 無往而不復 — Time’s Arrows, a chapter in six parts: Time’s Arrows; The Revolution of Resistance; Have We Been Noticed Yet?; Chinese Visions: A Provocation; On China’s Editor-Censors; Ethical Dilemmas — notes for academics who deal with Xi Jinping’s China; and, Fifteen Years of China’s Prosperous Age

***

Hu Shih: An Appreciation

Jerome B. Grieder

The following essay was written shortly after the death fifty years ago of Hu Shih (胡適, 17 December 1891-24 February 1962). At a time when what Hu Shi had called ‘the turmoil of the newspaper’ marks once more the understanding of China, it is timely to reconsider the work and contribution of this important liberal thinker and extraordinary cosmopolitan.

This essay originally appeared in The China Quarterly, no.12 (October-December 1962): 92-101. Jerome B. Grieder is the author of Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance: Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1937, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

— GRB, March 2012

The sudden death of Dr. Hu Shih in Taiwan on February 24, 1962, inflicted on many of the people of that island a sense of irreparable loss. This was not because the present situation in Nationalist China is likely to be much affected by Dr. Hu’s passing, for in spite of his great reputation as a scholar, his considerable personal popularity and the prestige of his position as President of the Academia Sinica, he remained a peripheral figure there. He was, however, the last surviving representative of the great generation of revolutionary intellectuals who, nearly half a century ago, undertook the enormous task of creating a cultural “renaissance” in China, and with his death a final link with that optimistic era was forever severed.

The “New Culture Movement” of the 1920s was the product of diverse inspirations and convictions. The one thing held in common by all who contributed to it was the hope that they could fashion a strong and enduring nation and people out of the chaos of the past. If Hu Shih’s death occasioned regret both in Taiwan and among his many friends in the United States it was because it served as a reminder that the intellectual revolution for which he worked has had an outcome far more harsh and oppressive than he had envisioned. Today we see in the Chinese revolution not a renaissance, but the birth of something unprecedented and disquieting.

For Westerners, accustomed in fancy if not in fact to the idea of oriental inscrutability, Hu Shih was a rare and pleasant phenomenon, a Chinese intellectual whom we had little difficulty in understanding. Urbane, sophisticated and affable, he spoke readily and with authority, and he smiled easily. His command of English was flawless. He first came to the United States as a student in 1910, and he lived in this country for nearly half of the more than fifty years that have elapsed since then, as a student at Cornell and Columbia universities, as China’s first wartime ambassador to Washington, and as a visitor after the collapse of the Nationalist regime on the mainland in 1949. Hu Shih did more than learn to speak the language of the West and move with assurance in its alien society. Very early he came to esteem the social and political ideals embodied in the Western tradition, and it was this that endeared him to his friends in this country and earned him the sympathy of many Americans in China who knew at first hand the situation he faced there.

Many influences, Chinese as well as Western, helped to shape his opinions. From his father, a minor official during the declining years of the Qing dynasty, he inherited an appreciation of the humanistic tradition of orthodox Confucian thought, and this contributed to the growth of a mature scepticism in which he incorporated also ideas borrowed from such Western sources as T.H. Huxley. His view of the relationship that should exist between the individual and society owed much to the dramatic works of Hauptmann and, particularly, Ibsen. The writings of John Morley, the doctrines of Woodrow Wilson, and Hu’s personal friendship with Norman Angell, the British pacifist, all influenced the development of his standards of national and international political behaviour. By far the most important single influence on him, however, came from Professor John Dewey, whose student he was at Columbia from 1915 to 1917. The methodology of Dewey’s pragmatism appealed to him because it provided an intellectual sequence through which to approach the problems of social change without necessitating specific assumptions as to the context within which change must occur. It was, in short, the application of scientific methods and attitudes to new areas of investigation, and throughout his life Hu emphasized this aspect of Dewey’s thought by referring to himself as an “experimentalist,” in politics as well as in scholarship.

Upon his return to China in 1917, Hu became a professor at Peking National University (Beida); his association with it lasted until 1949, interrupted for a decade during the war and for a briefer period in the late twenties when he resided in Shanghai. Throughout much of this time, Beida was the uncontested centre of China’s new intellectual life, and Hu’s position there brought him into direct contact with many of the most brilliant personalities of those years. A philosopher by education, a devoted student of Chinese literary history, a man whose quick mind and wide-ranging interests touched upon almost every aspect of China’s intellectual heritage, he was influential in directing and training such younger scholars as Gu Jingang 顧頡剛, the historian and folklorist, Yu Pingbo 俞平伯, the literary critic, and Luo Erkang 羅爾康, a specialist in the history of the Taiping Rebellion. (In 1949 all these men remained on the mainland, and in the course of the last few years each has repudiated his former teacher.) Apart from his activity as a scholar, Hu also sought to shape the views of his countrymen on contemporary problems, and his opinions on a broad range of social and political issues were published in essays that he contributed to a number of influential periodicals during the twenties and the thirties. It is possible that no other writer of his generation was read more widely, and in the minds of some he remains, even now, the greatest of the many who participated in the struggle to bring to China the benefits of enlightenment.

This was in large part a struggle against the deadweight of tradition, involving, among other things, a redefinition of the individual’s place in society, his emancipation from the claims of family, clan or native place, from the authoritarian hierarchy of inherited relationships, and from the beliefs of a bygone age. Thus Hu ceaselessly exhorted the young people of China, the middle-school and university students, to assume the responsibilities that the times urged upon them, to develop their individual personalities, to think critically and independently, and to remain mindful of their obligation to tolerate the ideas of others.

***

‘Tolerance is more important than freedom.’ — Hu Shih

Tolerance: allowing people to choose their own tastes and values and to pursue their own ends. But as an absolute, tolerance is no different from liberty or equality or the classless society. It is only another end, and it, too, needs values that cut against it. Should we be tolerant of intolerant people?

— Louis Menand, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, New York: FSG, 2021, pp.351-352

***

Hu Shih was not a political activist, nor even primarily a political thinker. He was convinced that a stable political settlement could be achieved only after the social patterns and intellectual assumptions of the past had been swept away, and his chief concern was the introduction of new methods of research and modes of thought by means of which he hoped to liberate the Chinese mind from the coercion of traditional attitudes and values. But the times through which he lived would not permit him the privilege of isolating himself from the political life of the nation, and it was repeatedly necessary for him to define his political views. His moderate or evolutionary approach to the problems of social change, his beliefs concerning the function of law as a political instrument, and his view of the role of the individual in society and government combined together to make him, in the broadest sense of the term, a political liberal. He was among the most articulate and consistent members of the relatively small group of publicists and scholars who attempted, in an environment of revolutionary tensions, to create an attitude of mind capable of, and a political climate favourable to, effective use of the instruments of democratic government.

Hu Shih affirmed the importance of the individual as a social and political end in himself, and he asserted that institutions have no legitimate purpose other than to promote the realisation of individual personality. He steadfastly believed that through education the individual could be made to comprehend the workings of his own society and enabled to participate usefully in the tasks of self-government. He envisioned a society less homogeneous than that idealised by Confucian theorists, and in it law—traditionally a negative factor in Confucian political philosophy—must play an important part, as the instrument by means of which opportunities for self-expression are created and protected. Thus Hu was a firm advocate of constitutionalism, which he viewed as a prerequisite to the political education of the people, and he insisted that only legally defined and defended liberties would enable an enlightened public opinion, the conscience of the nation, to function as it should.

Concerning the nature of the current crisis and the shape of the future, Hu Shih was at odds with many of his contemporaries. In an era of steadily increasing nationalistic sentiment he remained an avowed “cosmopolitan.” He rejected, on the one hand, the argument of those who laid the blame for China’s plight on foreign encroachment and the designs of “capitalist imperialism,” for if China was facing disaster, as he wrote in 1928, it was because her people were poverty-stricken, disease-ridden and haunted by ignorance. But on the other hand he jeered at the view expressed by certain traditionalist thinkers that China’s “spiritual” inheritance was morally superior to the “materialistic” civilisation of the West and destined ultimately to triumph over it. Time and again he argued that insofar as traditional ideas and attitudes had impeded the achievement of material well-being for the Chinese people, they had stunted the spiritual growth of Chinese society and culture as well. He denied, in effect, that human progress can be measured by a double standard, and he insisted that China must abandon her pretensions to uniqueness and accept the position assigned to her when judged against the evolution of humanity as a whole. He sought to push China out into the march of world history, where the pace was set by Western achievement, both technological and intellectual.

It is easy for Westerners to sympathise with Hu Shih’s efforts, for he spoke the language of a Western-oriented liberal intellectual. But this was not a language comprehensible to many Chinese, nor easily accommodated to the political and social conditions prevalent in China in the twenties and thirties. If Hu’s description of the problems China faced differed from the descriptions offered by others, so did the programme he put forward as a means of solving these problems. He was convinced that the only realistic and reliable approach lay in gradual and undramatic reform which would aim at the isolation of specific difficulties and then seek to resolve them “bit by bit, drop by drop.” For this reason he preferred to speak in terms of evolutionary change rather than revolution, and he was profoundly distrustful of emotional responses to any crisis, lest what he once called “the turmoil of the newspaper” divert attention from the fundamental tasks of intellectual reconstruction. While others preached extreme and all-encompassing solutions, Hu was a consistent advocate of moderation.

When we study this position against the unfolding history of China during those troubled years it is difficult to escape the conclusion that intellectuals of Hu’s persuasion were condemned to frustration and impotence by their own convictions. Until 1928 China was ruled by a succession of warlord regimes, all of which made some show of respect for parliamentary government but were in fact supported only by armed force of a most brutal and cynical kind. For Hu Shih and like-minded men, no participation in any of these governments was possible, nor did they possess any means of influencing governments so constituted. Their only recourse was to public opinion, by which they set great store. They did their best to arouse public opinion against the abuses of militarist politics by publishing demands for “good government” and for “government with a plan’—meaning, among other things, a published budget, public accounting, a civil service selected in accordance with well-defined standards of merit and rigorously controlled as to size, revision of gross injustices in the electoral process, and the disbanding of private armies. Such demands are themselves an indication of the political climate of the period, which doomed them to failure. The hopelessness of their situation was well demonstrated in 1923 when Cao Kun 曹錕, the warlord whose armies at that time supported the “central” government in Peking, bought from parliament his election to the presidency of the Republic in spite of a vigorous campaign waged against him in the pages of The Endeavor 努力周報, a small weekly paper founded by Hu Shih, V.K. Ting 丁文江 and others partly as an attempt to frustrate Cao’s ambitions.

After the unification of most of the country by the Nationalist armies of Chiang Kai-shek in 1927-28, China’s liberal intellectuals were faced with a new situation, and initially the prospects may have seemed brighter. The Nationalist government established in Nanking was, in fact, a “government with a plan.” Sun Yat-sen had committed his party to the eventual implementation of constitutional democracy when the people had attained a level of education and political experience sufficient to make democratic forms meaningful, and he had also left behind a schedule to be followed in the achievement of this end, a three-stage progression from military reunification through an ill-defined period of “political tutelage ” to the ultimate condition of democracy.

Under the Nanking régime, however, a new element emerged to complicate further the relationship between the intellectuals and those who exercised political power. Sun Yat-sen’s writings, vague and inconsistent as they were on some points, became after his death in 1925 the sacred texts of the Nationalist revolution, against which no appeal was possible, and no criticism tolerated. Instead of a “government with a plan,” China had inherited a government with an ideology. Taking Sun’s theory of political tutelage as its justification, the Nationalist government remained obdurately hostile to demands for the introduction of constitutional restraint on its powers, contending that political sovereignty could not be given over to the people until they had been instructed in its use. Hu Shih took the contrary view, asserting that only through experience could the people ever acquire the political understanding necessary to the proper functioning of a democratic nation. In 1928 and 1929 he published a series of “Essays on human rights” in which he criticised the logic of Sun’s philosophy and accused the Nanking government in pointed terms of insincerity and subterfuge in this regard. The government responded with a barrage of official rebukes and warnings, reprimanding Hu for “misleading such of our people as have not yet gained a firm belief in our ideology.” In an era when the due process of law seldom interfered with the permanent settlement of political differences, Hu got off lightly. In later years, under the pressure of changing problems and new dangers, a modus vivendi between Hu Shih and the Party leadership was achieved, but the issue was never resolved and Hu remained to the end of his life a representative of the independent intellectuals who belonged to “no party, no clique.”

During the 1930s the Nationalist government was confronted by the double challenge of Japanese aggression from without and increasingly bitter dissension within the nation. Unsuccessful in his attempts to exterminate the Chinese Communists in the mountains of Kiangsi, or later in their strongholds in the north-west, Chiang Kai-shek became convinced, almost to the point of unreason, that this internal dispute must be settled before the threat posed by Japan could be met. To this end the Nationalists increased the military pressure on Communist-held areas. At the same time they intensified their campaign against subversion among the intellectuals still within their reach and attempted to counteract the appeal of Communism by patching together a mass ideology of their own, a hodge-podge of refurbished Confucian maxims and pointers on personal hygiene which they called, hopefully, “The New Life Movement.” However perspicacious the Nationalist assessment of the situation at that time may seem to us now, the effect of its policies thirty years ago was only to increase resentment against it and to permit the Chinese Communists to appear more and more convincingly as spokesmen for the cause of national independence and political freedom. Throughout those anxious years Chinese writers and students and intellectuals-the men and women who shaped and gave expression to the “public opinion” in which Hu Shih had such great faith-drifted toward the political Left.

Among the factors that drew the Chinese mind toward the Left in the twenties and thirties was the recent history of China’s great neighbour to the north. Hu Shih himself was not immune to the appeal of the dramatic events taking place in the Soviet Union after 1917. His own firsthand experience with the Russian revolution was limited to a brief stopover in Moscow en route to Europe in 1926, but even this was sufficient to inspire his admiration for the sense of purpose and the willingness to experiment that he perceived there. In 1933 he went so far as to suggest—to an American audience—that Russian Communism should be regarded as “an integral part” of Western civilisation and “the logical consequence in the fulfilment of its democratic ideal.”

In spite of this, however, Hu’s break with Marxism-Leninism in China itself came early and was never compromised. At the time of the May Fourth Movement in 1919, when in the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution and the humiliating outcome of the Versailles Conference, Marxist thought was gaining its first adherents among the intellectuals of Peking and Shanghai, Hu recognised in it the antithesis of the mental attitudes and intellectual methods he himself wished to inculcate. In his view, Marxism-Leninism gave misleadingly easy answers to China’s problems, while with its talk of “feudalism,” “capitalism” and “imperialism ” it obscured their true nature. Its promise of a quick solution to all the difficulties China faced was founded on what Hu felt to be false assumptions as to the nature of society and of the revolutionary process. Hu’s distrust of the Marxist programme for China thus arose initially not so much out of a fear of its ultimate incompatibility with the cause of political liberty as from the conviction that it was based on intellectually authoritarian and “unscientific ” principles. The same conviction turned him, some years later, against the Nationalists’ attempts to establish standards of ideological orthodoxy.

As an “experimentalist,” Hu Shih was committed to the belief that truth is not absolute and that the correctness of any course of action can be determined only by reference to its consequences. Such beliefs lay a heavy burden on the mind of a would-be reformer in times of disorder and uncertainty. Hu Shih was better able to support this burden than were many of his contemporaries, for he viewed events in China with a remarkable degree of optimistic detachment. We may, perhaps, attribute this to his profound faith in human reason, even in a chaotic age. He did not believe that men are the instruments of economic or social or spiritual forces that lie beyond their control. He held instead that they are capable of shaping their own destinies if only they are permitted to think for themselves, unimpeded by the prejudices of the past or by erroneous impressions of the present. Because of this belief, Hu may justifiably be called a liberal thinker, and it endows his contributions to the intellectual life of modern China with a certain nobility.

But there are risks involved in remaining passionless in an impassioned age. Anger, frustration and despair can generate more heat than a cool appeal to reason can dispel. The sense of detachment, of emotional disengagement, necessarily maintained as a precondition of independent and critical thought may easily be mistaken for, if it does not in fact become, indifference to manifest abuses. Perhaps it was for this reason that Hu Shih, despite his reputation and his popularity, never seemed able to describe his beliefs to Chinese intellectuals in terms that could satisfy not only their minds but also the restless and inchoate yearnings of their hearts.

Early in 1916, at the time when Yuan Shikai, the President of the Republic, was engaged in his abortive attempt to overthrow republicanism and have himself inaugurated as the first emperor of a new dynasty, Hu Shih wrote a letter to an American friend that aptly foreshadowed the argument he would make throughout his life. Commenting on the course of events in China, he wrote with characteristic coolness:

I have come to hold that there is no short-cut to political decency and efficiency. … Good government cannot be secured without certain necessary prerequisites. … Neither a monarchy nor a republic will save China without what I call the “necessary prerequisites.” It is our business to provide for these necessary prerequisites—to “Create new Causes.”

From the time of his return to China a year later Hu dedicated himself to this task, seeking to instil into his people new habits of thought and action and in this way to mould the history of his nation.

The Chinese revolution was the first in this century of revolutions, and the longest. It remains today the least understood. Now, with the problems of underdeveloped nations so much at the forefront of our thinking we are perhaps better able to comprehend the complex interaction of social, political, economic and intellectual forces that have contributed to the transformation of China than we were forty-five years ago when Hu Shih set out “to create new causes.” Then it was still possible to conceive of revolution as an intellectual rebirth from which all things would follow in their own time and pattern. Hu Shih was not alone in emphasising this aspect of the revolutionary process, for one of the striking characteristics of the Chinese revolutionary experience has been the importance attached by all participants to the need for widespread intellectual involvement in it. This fact suggests that something of the Confucian belief that knowledge and action are inseparably linked, that action is impossible unless it is understood, has survived in the Chinese mind. In dynastic China such a belief was made tenable by the elitist nature of political leadership and by the politically passive role assigned to the peasantry. One of the features of the process of modernisation, however, is the need it creates for wider participation in the national cause, and in countries like China the chasm separating the enlightened few from the inertly ignorant many has become a problem of major proportions. The Nationalists had no answer to this problem. The Communists have attempted to meet it not only through regimentation of the population but also by means of unprecedented programmes for mass education and indoctrination.

***

***

Hu Shih and other moderates, taking the long view, were content to place their hopes on a future time when, by the slow and uncoerced diffusion of skills and ideas over a period of decades, a level of enlightenment sufficient to permit purposeful action by all would have become the common possession of all. Had this approach triumphed the result might well have been a more liberal society, but in effect the attitude adopted by these men tended to emphasise the present cleavage between the intellectual elite and the masses of the people. Hu Shih and others like him came to occupy a position similar in many respects to that of the scholar-officials of traditional China: sincere, humane and responsible men, obligated by reason of their superior endowments to protest against tyranny and speak on behalf of the people’s welfare, though never themselves of the people. They were the voice of mankind’s better nature, not the spokesmen of a popular cause.

Today the Nationalist government in Formosa, justifying its right to survive, claims that it alone represents and defends the great tradition that is China’s gift to civilisation. There is truth in this, certainly, for much that was humane and gentle and sophisticated in the Chinese way of life has been eradicated by the Communists in the last twelve years along with much that was unjust and cruel. The Nationalist claim, however, acts to obscure the character of China’s recent past and to distort the nature of individual contributions to her modern history, and it points up as well the intellectual and psychological dilemma confronting this remnant of a nation at the present time. After Hu Shih’s death Chiang Kai-shek composed and wrote out in his own hand a memorial scroll summarising the accomplishments of the man who had been one of his most reasonable, and at times his most perceptive, critics. Hu Shih, wrote the President, was

A model of the old virtues within the New Culture—

An example of the new thought within the framework of old moral principles.

新文化中舊道德的楷模,

舊倫理中新思想的師表。

There is no reason to assume that Chiang was doing more than paying his sincere respects to the dead. He was, perhaps, unaware of the fact that he had in a certain sense described the position into which Hu Shih had been forced by the circumstances of his own temperament and beliefs and of the times in which he lived. And surely Chiang Kai-shek had not intended to remind us, as he did nevertheless, that if his small realm is indeed the repository of what is good and true from China’s past, it is also the repository of the intellectual frustrations of the last several decades. Unable to forsake the past, unable to praise except in terms of ancient beliefs and values, it is the victim of a crisis of identity which may yet destroy it.

Westerners, and Americans particularly, cannot forget that much of what Hu Shih had hoped to do for China was what we ourselves would have wanted done. His death may rightly prompt us to ask ourselves again what may be the ultimate fate of the ideals of moderation, tolerance, the rule of law and individual liberty in a world torn by immoderate and brutal revolutions.

***

Source:

- Jerome B. Grieder, Hu Shih: An Appreciation, The China Quarterly, no.12 (October-December 1962): 92-101. Wade-Giles romanisation in the original has been converted to Hanyu Pinyin, except for the name Hu Shih, and Chinese characters have been added.

When the ’62 Scholars Reconsidered Hu Shih

***

重思胡適

任劍濤主編

北京:中央編譯出版社,2015年

導言

上編 胡適思想的再認知

胡適:新舊之“中庸”,高全喜

基於庸見的法意——胡適之先生關於憲政與法制的看法,許章潤

信念與錯覺—評說胡適在“民主與獨裁”論戰中的一些觀點,單世聯

重建儒家視野里的胡適——論胡適與儒家,陳明

胡適與國家認同,任劍濤

下編 胡適話題的再探究

胡適與司徒雷登:兩個跨文化人的歷史命運,歐陽哲生

胡適自由主義與當代中國—兼論中國國家發展歷程,燕繼榮

胡適“自由夢”的經濟基礎,陳志武

中國的復興與自由主義的理論難題,胡傳勝

附錄

胡適思想的當代考察——紀念胡適逝世五十週年學術討論會實錄

後 記

***

重思胡適

導言

1962年,胡适去世;1962年,我们出生。

这当然是生命长河中偶然碰巧出现的两件事情。但无巧不成书。往往正是偶然出现、且不大相关的事情,一经关联性思考,就出现了某些令人惊异的内在契合。

在2012 年,1962年出生的几位学人茶聚,说起这一年中国的种种大事小事,总觉得跟“百无一用是书生”的我们没什么关系,于是大家想做一二件事情,以志我们在这一年活过。说来说去,胡适1962年的仙逝,成了大家的共同话题。议论来议论去,大家觉得不论是就我们恰好这一年出生的偶然巧遇而言,还是就中国的现代转变来说,都值得为胡适召开一个专门学术会议,以便以一个较为正式的形式,表达我们对胡适的深刻纪念,也自我提醒知天命之年的我们,得为国家的发展思考一些更为重要的问题。由于2012年的中国处在一个特殊政治年份,因此,是次会议不得不放到接近年尾的时间举办。好在会议开得非常热烈,学术上也有一定收获。于是,在会议上,与会者达成共识,将提交会议的发言稿修订成正式论文,并交付出版,以便将这一次富有意义的胡适纪念会记载下来。

胡适是启动中国现代转轨的一代思想重镇。他的思想贡献是多方面的。以其社会影响而言,他对新文化运动,尤其是新文学运动的影响,既广泛深刻又持续久远;以其对政治转型的作用而言,胡适是以自由主义的代表人物载入史册的。前者,似乎可以说是完全竟功,今天中国的文化形态已经转进到现代的结构;后者,就其所期待的政制建构来讲,言之成功,则远未可期。但胡适所指示的方向,绝对是正确无误的。在古今中西的强烈碰撞中,胡适为转型中国刻画的蓝图,究竟是不是可以在中国未来的发展中变成现实,自然是一个历史过程才能显示答案的问题。不过,一切关心中国现代转型话题的人们,试图绕开胡适去申论相关主张,那却是不太可能的事情。

胡适的思想有一种不温不火的性格。不是说胡适没有激进的主张,支持全盘西化,就至今为人所诟病;也不是说胡适就没有维护传统的一面,他使美时期对中国传统文化的辩护,甚至显得有些迂腐。但总体上说来,在中国文化急遽转型的历史剧痛阶段,他并没有走向偏执和极端。他深切感到中国传统文化已经不适应现代转变之需,因此呼吁转型中国接受西方文化。但他并未因此提倡“不读中国书”。他自觉意识到中国接受现代西方文化的必要与重要,但并未走向一偏,即使提倡自由,但更强调“容忍比自由更重要”。正是因为如此,胡适的思想给人们一种矛盾重重的感觉:说他开怀拥抱现代,他一生却又花费了巨大精力,致力于整理“国故”;讲他潜心整理国故,却又对西方现代学术推崇有加。这不仅矛盾,而且有点两头不着岸的尴尬:整理国故,人们并没有将他视为与传统亲和的保守人士;引进西学,人们也没有将他看作现代学术的创制人物。这是他去世时被人认定为“新文化中旧道德之楷模,旧伦理中新思想之师表”最重要的缘由之所在。在中国需要作别传统、进入现代的情况下,胡适缺乏决绝的态度,自然处在一种吃力不讨好的争论漩涡之中:亲和传统的人士,对胡适切齿痛恨;支持现代的人士,对胡适缺乏创造备感遗憾。但不得不承认,现代学术的引入,缺乏胡适的努力,可能会出现巨大的缺失;传统的整理,缺乏胡适的倡导,可能会丧失现代生机。这就是胡适具有不可替代的现代思想史地位的扎实理由所在。

百余年来,中国的现代转变总是处在一种进退失据的状态。历经晚清、民国与人民共和国三个阶段,但中国完成现代转型的历史任务,似乎仍处在艰难困苦的境地。在三个不同阶段上,人们对这一困扰中国人的处境,充满愤懑之情。这是完全可以理解的状况。但也正是因为如此,多少身怀振兴国家雄心的志士,生发浩叹、痛心疾首,不断发出惨痛的批判之声,决绝地斥责现实,绝望地看待未来。鲁迅是其中重要的代表人物。鲁迅对中国国民性的痛切诊断、对中国现实的绝望观察、对传统文化弊端的深刻指正、对现代中国发展的痛心疾首,跃然纸上,活生生显示出一个“新旧杂陈、方生未死”的中国那种无望的精神状态。与胡适相比较,鲁迅的精神气质与其相差何止千里。这是今人祭出“要胡适,还是要鲁迅”话题的动力所在。

其实,胡适与鲁迅并不那么对立。如果把鲁迅看作是中国人不得不“送旧”的代言人的话,他那种决然而然的批判态度,对传统、对现实的决不妥协,以匕首和投枪战斗的姿态,恰好凸显了中国作别传统的艰辛状态。如果把胡适视为中国人进入现代不得不“迎新”的传声筒的话,他那种试图混合古今中西精粹以逼进现代的取向,也恰好显示出中国进入现代的曲折复杂。鲁迅与胡适之所以作为中国现代文化的两面旗帜,不存在要谁不要谁的客观理由,只存在偏重哪个面相的主观偏好。对此,只有那种深刻领会了对中国转型之难而引发的愤恨的人,才能理解鲁迅;也只有那些领悟了中国转型中理性的绝对重要性的人,才能与胡适相契。基于此,人们就有了平情对待鲁迅与胡适的理由。正是基于这样的理性态度,我们也才在死与生的偶然继起性中,发现了我们纪念胡适的特殊价值。

胡适,以及鲁迅,总是站在国家转轨的十字路口,提点人们。他们是观察、论述中国现代转轨的智者。在那个时代,他们以自由的心灵,触碰严酷的现实。不论是对现实强烈不满引发的愤慨,还是对未来发展的充满期待,他们都没有被现实所摧折、被压力所弯曲、被挫折所屈服,他们对国家和未来怀抱深切的期望。这正是表明他们心灵自由的最可贵的地方,也是今天的我们与他们在精神深处相契合的地方。

鲁迅对现实的极端愤慨是可以理解的。但却是无法模仿的。他那种决绝的姿态、入木三分的文辞、终生不妥协的作为,不是一般人所可以习得的。相比之下,胡适的可学性较强。胡适较为平实的人生取向、宽容待人的态度、中庸的为学方式,比较符合常人的思维与行动进路。当然,胡适也不是一般人即学即成的。他是大师,是一般人敬仰的对象。不过就一般人来讲,面对胡适,有一种相对亲切的感觉,“虽不能至,心向往之”。与胡适那种自由而宽容的心灵相交,自然也就亲和很多。

探究胡适的思想,自然不是我们的直接目的。因为我们这群学者,除开一位公认的胡适专家外,其他人从未专门处理过关系到胡适的学术话题。几乎是一群胡适研究的门外汉,却要来专门论道胡适,也许会引起人们的讪笑。但我们也自有论说胡适的切实理由:不仅是因为他逝世的时候,我们刚好出生,似乎有一种人生—精神继起的禀赋。但这完全是不成理由的理由。关键是因为,胡适一直是我们各自所从事的专业研究的重要参照人物。尽管大多数论者没有专门研究胡适,但胡适未尝完全离开我们的关注视野。只不过此前缺少一个契机,让我们来专门整理自己对胡适相关论说的看法或学术见解。而这次,确乎有了一个申述各自关于胡适与自己专业研究关联性的机会。自然,由于参会者各自的专业视角和关注点的不同,切入胡适论题的角度便大为不同。不过从总体上讲,最后参会者提交的论文,可以切分为两个视角:一是论述胡适本人的思想,二是分析胡适开启的相关论题。

前一部分有五篇论文。

高全喜的论文“胡适:新旧之‘中庸’”,致力勾画胡适的思想性格。文章从蒋介石在胡适逝世撰写的挽联说起,解析胡适何以成为“新文化中旧道德的楷模,旧伦理中新思想的师表”。胡适与蒋介石一生多相交集。胡对蒋,有尊重,有批评,有苛责;蒋对胡,有愤懑、有嘉许、有期待。彼此还算是一种君子之交。但蒋胡之间似乎总有一种惺惺相惜的感觉。所以胡对蒋有微词,但总还护着蒋;蒋对胡有不满,但总还是能够容忍。蒋对胡适一生的概括,确实比较准确地勾画了胡适的思想与人生特质。蒋胡有君臣之名,更有敌友复杂关系。双方能够相容,而没有走向一种决然的敌对状态,不能不说与胡适、当然也与蒋介石的中庸性格相关。在近代以来的中国“古今中西”风云际会之际,这也是一种被时代所约定的精神品质。这种“不显山不露水”所显现的“极高明而道中庸”,呈现出一种现代中国人的独特风骨。

单世联的论文“信念与错觉——评说胡适在‘民主与独裁’论战中的一些观点”,对20世纪30年代那场关乎中国政治发展道路的大争论进行了回顾和评价。1934到1937年的“民主与独裁”论战,具有全国性的规模,仅就发生在胡适等人编辑的《独立评论》上的文章而言,第一阶段的主题是中国如何统一,第二阶段的中心是中国应取何种政制。论战主要发生在知识界,对中国实际政治生活并无明显影响,但其言论所涉,却是百年中国文化始终难以回避的艰难选择,而其中的有些观点,我们现在也不难听到。胡适在论战中写了不少文字,其根本主张是中国搞不了新式独裁,搞“新式独裁”的后果只能是“旧式专制”。胡适对“现代式独裁”的独特解释包含着若干依然有效的问题,比如复杂社会中政府权力的扩张、技术专家的参政、民主的训练等等。重温古典自由理念,我们依然需要正视民主在当代世界的种种“新形式”。回顾胡适在“民主与独裁”论战中的观点,不但可以从另一个角度理解社会主义在中国的传播,也有助于澄清当代中国社会主义民主建设的若干问题。

陈明的论文“重建儒家视野里的胡适——论胡适与儒家”,强调指出,胡适出身徽州儒学世家,自幼受正统的儒家教育,留学美国期间也长期以孔孟和朱子之徒自居,就是在新文化运动的激烈期,也从未对孔孟口出恶语,更是精思十多年作成平生得意之作《说儒》,胡适晚年的秘书胡颂平在《胡适之先生晚年谈话录》中多处记录了晚年胡适对孔子和儒家的称道。可见,一般印象中胡适是全盘西化论者、全盘反传统主义者,实际是片面的。研究胡适与儒家的关系,我们实际上已经看到,他所伸张的“充分的世界化”,其实是一个文化政治问题。胡适将充分世界化和天下观真正的重建两相联系,正是基于此,胡适对儒家的消解太过头,对重建儒家的现实重要性认识不足。反思胡适与儒家的关系,在重新认识胡适的同时,也要重新认识儒家,重新思考重建儒家的意义。

任剑涛的论文“胡适与国家认同”,明确指出,在中国从古典帝国向现代民族国家转型的过程中,人们必须重新建立自己的国家认同。胡适也处在这样的状况中。对于胡适而言,古典帝国时代的中国文化,始终是他要表达忠诚和倾慕的对象。但在文化意义上的“祖国”与政治上正在建构之中的现代“中国”之间,胡适的国家认同出现了相当程度的紊乱。对于祖国的传统文化,胡适一直是尊重和自豪的。但对于建构中的现代“中国”这一政治实体,由于没有坐实在他所理想的宪政民主平台上,因此他的认同态度是复杂的:对于20世纪中国建构的两个政党国家而言,胡适均不太认同,但对两者的具体认同态度又有明显差异。而在中国与美国的国家建构与认同差别的体认上,胡适确定了自己国家认同的典范形式——宪政民主国家,并期待中国的国家建构能够落定在这样的国家平台上。

后一部分有四篇论文。

欧阳哲生的论文“胡适与司徒雷登:两个跨文化人的历史命运”,首先确认,胡适与司徒雷登是中美文化交流史上两位重量级历史人物。胡适日记为人们找寻他与司徒雷登、燕京大学交往提供了诸多线索,司徒雷登回忆录等材料则可显现他对胡适、北京大学的看法。胡适与司徒雷登在教育、外交方面相似的经历为他们的交谊奠定了基础;而对基督教的不同立场又预示了他俩之间的矛盾。胡适与司徒雷登之间的对话,为处理世俗与宗教的关系提供了新的样板,是我们研究中美文化交流史值得解析的典型案例。司徒雷登站在宗教立场上、胡适站在世俗立场上看待相关问题。胡适与司徒雷登在种种问题上表现的立场和调整,不过是中西矛盾发展到新阶段的典型表现。他们之间既对话、争论,又彼此容忍,这就为处理世俗与宗教的对话提供了新的样板,也为中美文化交流展示了取长补短、求同存异、互相适应这一新的趋向。

燕继荣的论文“胡适自由主义与当代中国——兼论中国国家发展历程”,基于1840年鸦片战争以来,古老的中国面对“三千年未有之大变局”,指出中国的表面变局是中国经历“丧权辱国”到“民族复兴”的演变;实质变局是,中国从天朝上国的迷梦中清醒过来,试图实现传统“天下型”国家向现代民族国家转变。在这种古今之变、中西相遇的变化中,中国遭遇了严峻的“国家性危机”(stateness crisis)。晚清覆亡,旧的政治秩序解体。如何建立起一个对外能够维护国家主权、对内能够实施有效统治的现代国家,成为中国最为急迫的任务。面对危机,国共两党都沿用苏俄革命的经验,通过党治国家形式,实现建立现代国家、挽救民族危亡的目的。胡适对国共两党都持批评态度,这既是其自由主义的思想基底使然,也是其渐进改良“实验主义”哲学观念之必然。跳出简单的革命与反革命、资本主义与社会主义的思维模式,从“国家性危机”以及“以政党挽救国家”的危机应对方式的视野来考察中国近代历史,能够更好地体认和阐发胡适思想的时代价值。

陈志武的论文“胡适‘自由梦’的经济基础”,在综合考察五四以来中国思想界的思想倾向后,指出:五四时期与之前的中国社会运动相比,最大的不同在于其旗帜鲜明地以个人自由为目标,以知识启蒙和新文化为具体手段。那场启蒙的影响是如此深远,它决定了过去近一个世纪中国社会方方面面的命运,其中也不乏因认知盲点带来的灾难。当然,回头看,那次启蒙运动的主要参与者从激进民主主义的陈独秀、李大钊到改良自由主义的胡适,存在着共同的知识结构缺陷,即都以人文哲学为主,对现代经济学了解甚少,以至于他们虽然都号称追求自由梦,但对自由梦所需要的基础制度只有模糊的理解,不清楚私有制和市场经济是个人自由的基石条件。这些认知缺陷使他们除了热衷自由的价值取向外,没能为这一价值追求找到成功的具体实现手段。在我们今天研究五四思想史的时候,有必要避免同样的认知盲点,最好能用现代经济学以及其它社会科学范式去审视胡适等知识分子的思想世界,从而为“自由梦”夯实经济基础。

胡传胜的论文“中国的复兴与自由主义的理论难题”,首先指出了一个悖谬的现象,一方面中国的复兴是21世纪世界历史的最重要现象之一。最敏锐的中国问题专家甚至也没有预料到这个现象。另一方面,1989年以后至少十年时间,不少人认定,中国的崩溃似乎指日可待。在西方的意识形态中,中国的崩溃似乎是国际共产主义或全球专制政体的最后亦是最大的失败。至今,中国崩溃与中国威胁仍然成为关于中国的两个最生动的想象。其次,作者对这样的悖谬进行了分析,强调指出,一方面,中国的复兴或富强并不全是虚构。不承认这点并不明智。中国的复兴遵循的是中国文化原有的模式。另一方面,中国的复兴不仅是自由主义解释不了的、与自由主义无关的,甚至是根本反自由主义的。从思想史的角度来看,中国的自由主义话语是属于富强或民族尊严重建这个更大的话语的,而一旦中国的富强通过非自由主义的手段获得,这就为自由主义提出一个理论难题,尤其是自由主义已经成为中国思想的构成性因素时。

论文之后,附上了1962学人纪念胡适逝世50周年学术讨论会的会议发言实录。本来,发言中的大多数话语,已经为发言者写入了论文中,似乎没有必要收入本书。但读者阅读发言实录后可以发现,在会议进程中各位发言人的发言,不仅比书面语言显得活泼,而且因为是在严肃的学术对话中申述自己见解的,因此更增加了一种相互攻错的论辩性,这无疑有助于发言者甚至是阅读者在不同意见中有效整理自己的思绪。因此,将之收入书中,似乎不为多余。

这些论文,凝聚了写作者的深入思考和专业见解。其中,有若干论题是以往的胡适研究中较少提起或重视不够的。水平如何,得由读者评价。但我们的态度非常诚恳。这种诚恳的态度,不唯是对先贤胡适的,也是对我们自己1962学人所在的学术群体的,更是对转型中国需要深入剖析的理论问题的,自然还是对读者诸君的。经由现代先驱探究中国转型问题,是我们共同确立的群体研究志向,愿与同道和读者一起付诸实践。

1962学人以纪念胡适为契机的学术聚会,只是这批学人学术聚会的一个起点。这样的聚会会不会有些许学术创获?难说。一切望诸将来吧!时间,才是量度一切的刚性尺度。

***