Viral Alarm

Viral Alarm, the theme of China Heritage Annual 2020, was inspired by ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’, an impassioned critique of Xi Jinping, his government and their disastrous initial response to the COVID-19 epidemic written by Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤. He released that essay on 2 February 2020, not long after Lunar New Year celebrations ushered in the Gengzi Year 庚子年 of 2020-2021.

A ‘Gengzi year’ 庚子年 occurs every thirty-seventh year in China’s traditional sixty-year lunar calendrical cycle. In modern times, and in the popular imagination, ‘Gengzi years’ are associated with disaster and hardship: the Gengzi year of 1840 coincided with the First Opium War with Britain; 1900 was the year of the calamitous Boxer Rebellion that ended with the imperial capital of the Qing dynasty being occupied by foreign forces; and, 1960 marked a harrowing period of the Great Famine, itself the murderous result of the Great Leap Forward policies previously launched by Mao Zedong and the collective leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

The Gengzi Year of 2020-2021 has been similarly momentous, both for China, and for the rest of the world, the fate of which, for better or worse, is now inextricably bound to that of the People’s Republic of China.

Our translation of Xu Zhangrun’s essay ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’ appeared first in ChinaFile, published by the Asia Society in New York, and then in China Heritage. It was part of our continuing efforts to introduce our readers to the dissenting ideas of Xu Zhangrun and to track his fate after he became the most outspoken critic of Xi Jinping, the Communist party-state and the direction of the People’s Republic, both internally and on the international stage. (For details, see the Xu Zhangrun Archive on this site.)

On the morning of Monday 6 July 2020, Xu Zhangrun was suddenly detained by the authorities. Jailed on the spurious charge that he had ‘solicited prostitutes’ during a trip with friends to Sichuan in late 2019, Xu was kept incommunicado. During that time, Tsinghua University informed him that he had been fired from his position as a professor of law at that institution, that his accreditation as an educator had been withdrawn, that he was to vacate his apartment on the university campus and that he had been stripped of his pension. On Sunday 12 July, he was released as suddenly as he had been detained. (For details, see: ‘Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People’, China Heritage, 13 July 2020.)

Graduates of and supporters at Tsinghua immediately launched a campaign to crowdsource funds to support the now indigent former professor. Touched by their generosity, but determined not to burden his friends, Xu Zhangrun wrote a letter declining the funds. A translation of that letter appeared in this journal under the title ‘Responding to a Gesture of Support’ (China Heritage, 19 July 2020).

The following month — mid August 2020 — Xu Zhangrun was formally appointed to the honorific and unremunerated position of Associate in Research at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University. Xu wrote another letter, this time to thank friends and colleagues at Harvard for their timely gesture. A translation of that letter also appeared in this journal, under the title ‘A Letter to the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University’ (China Heritage, 19 August 2020).

In September 2020, Xu Zhangrun composed two more letters: ‘A Letter to China’s Dictators: On the Detention & Incarceration of Geng Xiaonan’; and, ‘Questioning China’s Scholars of Criminal Jurisprudence’, translations of which also appeared in these virtual pages.

As Professor Xu notes below, after writing these letters he decided that they would be part of a series of ten epistles in which he would address the eventful Gengzi Year of 2020-2021.

China Heritage has published translations of four of Xu Zhangrun’s Ten Letters from a Year of Plague and three more will appear with ChinaFile, the online magazine produced by the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society.

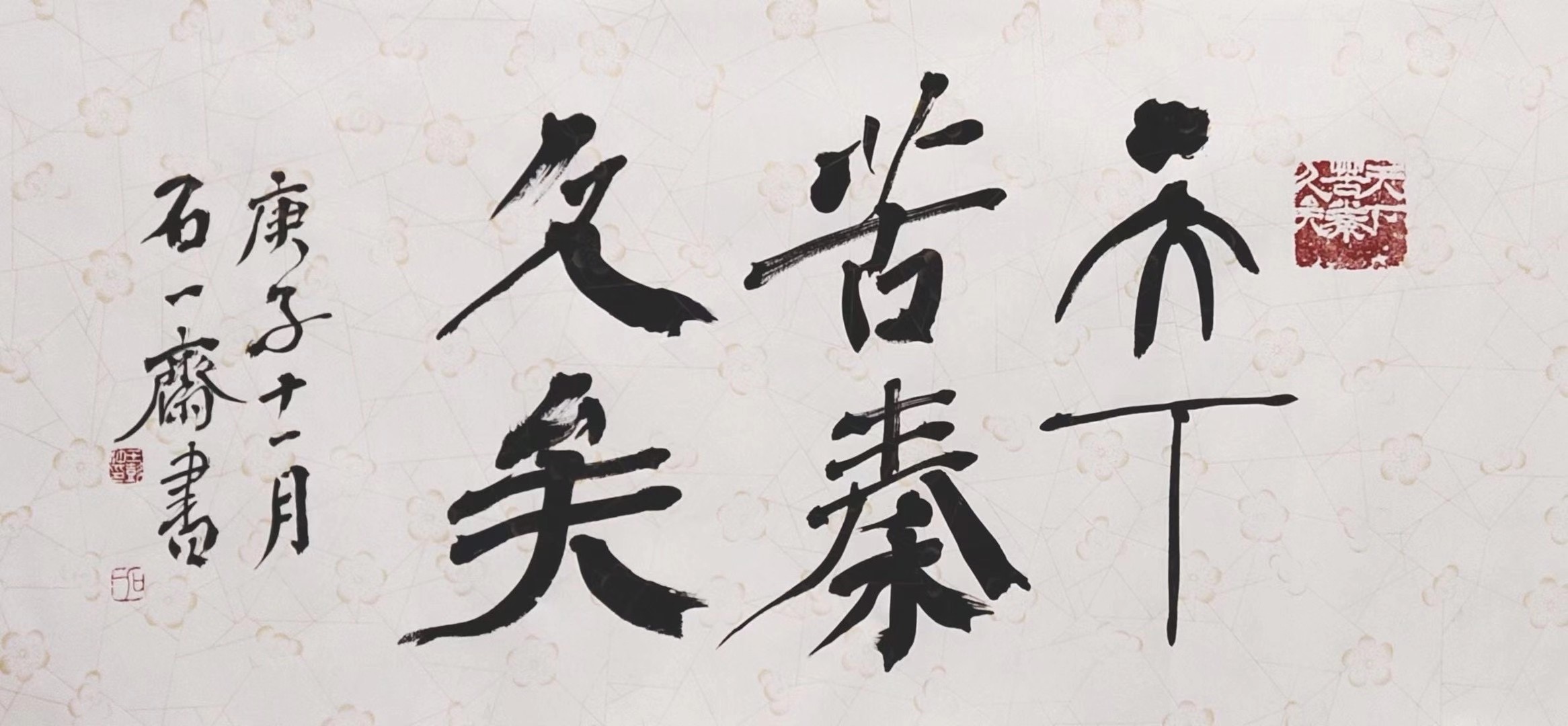

We began the Lunar Gengzi Year of 2020-2021 with Xu Zhangrun’s work and we end it with the Introduction to his book,《庚子十劄》Gēngzǐ shí zhá — Ten Letters from a Year of Plague. The Postscript to the book, which Xu Zhangrun composed on the last day of the Gengzi Year (庚子年除夕, Lunar New Years Eve), will appear in these pages during the Xinchou Year of the Ox 辛丑牛年, which starts on 12 February 2021.

We are profoundly grateful to Professor Xu Zhangrun for permission to publish this essay and to Reader #1 for timely emendations.

***

Xu Zhangrun’s book, Ten Letters from a Year of Plague 《庚子十劄》, was published by Bowen Books in New York on 4 August 2021.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

11 February 2021

Lunar New Years Eve

庚子年腊月三十除夕

***

Further Reading:

- Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020

- Xu Zhangrun, ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018

- Zi Zhongyun 資中筠, ‘1900 & 2020 — An Old Anxiety in a New Era’, China Heritage, 28 April 2020

***

Ten Letters from the Gengzi Year

Table of Contents

《庚子十劄》

目录

Introduction / 引言 [bilingual text below]

Letter One 一劄/ 致敬清華校友 [bilingual text, here]

Letter Two 二劄/ 致謝哈佛諸君 [bilingual text, here]

Letter Three 三劄/ 致叱暴政 [bilingual text, here]

Letter Four 四劄/ 致疑刑法學家 [bilingual text, here]

Letter Five 五劄/ 致念女兒 [‘From My Anguished Heart — A Letter to My Daughter’, ChinaFile, 21 July 2022]

Letter Six 六劄/ 致責胥吏衙役

Letter Seven 七劄/ 致候門下諸生 [‘A Farewell Letter to My Students’, ChinaFile, 9 September 2021]

Letter Eight 八劄/ 致知編輯同人 [‘A Letter to My Editors and to China’s Censors’, ChinaFile, 18 May 2021]

Letter Nine 九劄/ 致思思想

Letter Ten 十劄/ 致意這個美好人間Postscript 後記

***

Introducing

Ten Letters from the Gengzi Year of Plague

(2020-2021)

《庚子十劄 · 引言》

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

translated by Geremie R. Barmé

The lights of the village are extinguished

I wander now in a no man’s land,

Seeking to rent a place in nothingness.而村子裡的燈火都已熄滅。

於是我在無主的土地上徘徊,

向無生界請求租房。

— from Joseph Brodsky

‘New Stanzas to Augusta: VII’

約瑟夫·布羅斯基

「獻給奧古斯塔的新四行詩」

The ten letters, both long and short, collected here were written during the 2020-2021 Gengzi Year. The first was composed in that cruelest month of July 2020, when the heat of the summer was at its height and the lotuses cast their cooling shade over ponds and lakes throughout Beijing. The final letter was put to paper in the twelfth month of the lunar year [early February 2021], by which time the landscape was as desolate and desperate as the human realm itself.

These letters are a response to the efforts of the Chinese tyranny to silence me, to crush my spirit and to ban my thoughts, all on the most spurious of grounds.

So, I have chosen to rebel by writing and I have forged ahead confident in the rightness of my cause. I dared to raise a cry of alarm and they cast me into jail for my efforts. That was an unexpected interlude on the troubled path that I travelled over this Gengzi Year. By the time they released me I had been stripped of everything I had spent a lifetime working to achieve. To suffer a fate such as this as I was approaching my sixtieth birthday only served to further embolden me to act up in defiant righteousness. How could I complain as I challenged injustice?

長箋短劄,合共十通,均作於庚子年間。起自惡月,時當暑熱,荷塘照影; 終於臘月,萬木蕭疏,人間酷烈。事緣暴政箝口,刑戮思想,欲加之罪,何患無辭。在下以筆起義,秉義直行,放聲吶喊,遂致鋃鐺羈獄,庚子生命逆旅遂憑添一站。待出大牆,平生積累,剝奪殆盡,而孑然一無所有。年近花甲,遭此厄運,求仁得仁,亦何怨哉!

As all of this befell me, those I had once regarded as colleagues were now as strangers; it was as if they had made a collective decision to steer well clear of me. A galaxy of friends fell away like a meteor shower. My home life, too, was undone; all that had been was no more. Unemployed and in rustic solitude I found myself cut off from human society with only the company of my books and the solace offered by writing. The ancients are my companions now and in my reading reveries unhindered we travel together. I expect that this is how I will spend my allotted time.

當此之際,同人皆成路人,集體走避,避之惟恐不及。而舉世鰓鰓,友朋星散,家室不存,流水落花。無業孤居,鄉野獨處,音訊斷絕,唯讀書自娛,作文遣懷,引古人作伴,與今人冥遊,晨霧晚風中打發殘生。

I was, however, fortunate for friends at Tsinghua of stalwart character did not abandon me and they immediately set about crowdsourcing funds for my support. Overwhelmed by their kindness I felt nonetheless compelled to write and say I couldn’t accept their generosity. It was at this very juncture, too, that colleagues at Harvard University extended a chivalrous hand and offered me an appointment. I was deeply moved by their gesture. During one long sleepless night after I had written letters acknowledging these gestures of kindness [see here and here], it dawned on me that I had much more to say. That’s when I decided to compose the ten letters that make up this collection. They have been my way of finding an outlet, as well as a sense of purpose. Through these letters I bear witness to the absurdities of these vile times.

As the autumn chill encroached, that Warrior Woman [Geng Xiaonan 耿瀟男] was jailed, much to the horror and outrage of the world. In a mood of fury and anguish I initially composed ‘A Letter to China’s Dictators’; and, thereafter, I addressed ‘Another Letter to The Tyranny’ [Letter Six, which was released on the 9th of February 2021, the day that Geng Xiaonan was sentenced to three years in jail].

‘A violent beast has broken in; so threatening that even weaklings perforce take up arms’ [as Mao Zedong wrote in an early poem]. The only weapons that a meek scholar like me has to hand are pen and paper. I expect and want nothing, so why should I be afraid? Then, at this point my daughter, having completed her studies [in Australia] decided to return. Just as she was preparing to set off on her return travels, facing an uncertain future [I addressed a letter to her — that is, Letter Five]. Then there were all the students that I have been forced to abandon, left without guidance. I sorely felt the guilt of a wayward parent [and wrote Letter Seven to them].

My very being felt engulfed by all of these attachments and concerns. I could neither ignore them nor get past them, for they were choking my spirit and filling my thoughts, crowding every waking hour and every corner of my world. I had to find a way to express myself and I have done so in these letters. They are my way of marking the passage of this lethal Gengzi Year. They are also my way of paying homage to the wondrous glories and bitter realities of life.

幸清華校友不棄,先則募款賑濟生計; 賴哈佛諸君仗義,繼則延聘引為同儕。心有戚戚,不能自已,寸箋壁謝,銘感五內。二劄既竟,長夜難眠,不鳴不快,遂生連作十劄念頭,以不倦之思撫慰安頓人生,在艱難時世中為時代荒謬作證。時值秋涼,俠女入獄,舉世大譁,悲憤難抑,秉筆疾書,於是有「致暴政書」前後兩劄。暴虎入門,懦夫亦當奮臂,秀才手無寸鐵,唯有紙筆,無所求矣,何所懼哉。恰在此際,女兒學成,執意返國,轉眼將歸,前途未卜; 門下諸生,學業失怙,學思失恃,孑然孤立,來去無依。凡此牽掛,繞不過去,躲避不了,堵塞心頭,凝結為心事,纏繞成心思,蒼茫於廣宇,乃爛漫催生出後續諸劄,以誌此肅殺庚子,而向這個美好卻酷烈的人間致意。

I have been thinking too of a few close friends who, despite the looming threats of our times and their stretched circumstances, have stayed loyal throughout, constant in their expressions of concern and good will. Then there are those messages I have received from distant friends who really understand me. The words and their decency will stay with me and succour me forever.

These Ten Letters, collected in a single volume, will first appear overseas. They tell a story about those things that have most affected me this year, as well as crystallising my thoughts in a way, I hope, that offers some insight into life Within the Great Wall. Perhaps the sentiment of tragic outrage may offer something that will resonate with the like-minded.

I am, to all intents and purposes, in internal exile, someone stymied by partial supervised detention at home. All I can do is rail in agony, my impotent cries echo back at me unheard. Don’t forget, [as the ancients said] it is easier to dam a raging river than it is to silence people. And so this is how it is for me; it is a sad yet still joyful existence since, although I am a virtual prisoner reduced to poverty, my mind remains free and I may yet survive by writing. My heart and words are pellucid as I wander, an intellectual itinerant seeking alms from all sentient beings and finding solace in the skies above and the broad earth beneath my feet.

尚念三五摯友,板蕩時窮,近問遠候,不離不棄。海疆天宇,知音傳鴻,友之以文,誼之在義,堪慰平生。十劄既畢,輯集刊行,海外廣布,既在載述心事,坦露心思,以覘牆內人生,更為嚶其鳴矣,「笳一會兮琴一拍」。身陷半軟禁半流放狀態,空山悲號,壑谷有聲。而防⺠之口,甚於防川。如此,在下動囚坐困,恃思行腳,賣文掛褡,坦誠於心口,乞食於眾生,俯仰於天地,何其悲夫,不亦快哉!

I began this work on the Fourth Day of the First Month of the Gengzi Year [that is, 28 January 2020] when I wrote ‘When Fury Overcomes Fear’, and I brought it to a conclusion on the 28th Day of the Twelfth Month [9 February 2021] when I finished writing the tenth and final letter in my series. It is titled ‘Paying My Respects to a World That Abounds in Beauty’. This yearlong effort — a tireless and a taxing undertaking — has now drawn to an end. I’ve traversed a harrowing path and the sparse stars above twinkle silver just as my hair has turned grey as if in response.

In composing these Ten Letters I have sought to assuage my wounded heart and to express some thought that I hope will resonate with people everywhere. My words will, I believe, somehow find their way back to the land that gave them birth. Surely, they must do so and, when they do, maybe, just maybe, I will still be alive; we will still all be alive.

When that time comes, surely we will let out a harrowing sigh of relief, our faces awash in tears — in mourning for our miserable fragility along with the suffering we have endured, acknowledging our endless loss of hope, as well as our soaring dreams. And, then, may our voices resound in joyful song!

庚子作業,以正月初四「憤怒的人⺠已不再恐懼」一文始,而以臘月二十八最後一劄「致意這個美好人間」終。全年勞作,匪懈匪怠,至此收工,踏莎行,天也星星,鬢也星星。十劄既畢,旨在求一己之心安,以待天下萬眾之同慨。這些文字還將回到祖國,也必將回到祖國。也許,她們回歸祖國之時,我依然活著,我們依然活著。那時節,因我們的懦弱與苦難,為我們的絕望和夢想,念我們的永生與必死,共其一嘆,痛哉一哭,慨然一歌!

‘Mich im Arsche lecken!‘

「舔我的屁股吧!」

[‘Kiss my ass!’ — a line from Götz von Berlichingen by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a play about an irrepressible maverick knight who shouts these words when called on to surrender.]

Zhangrun

Twenty-ninth Day of the Twelfth Month

of the Gengzi Year (2020-2021)

The 10th of February 2020

Written by the Old River Bed

In the looming shadows of dusk

章潤,庚子臘月二十九

耶誕2021年 2月10日

暮色蒼茫,故河道旁。