Watching China Watching (XXXI)

… the only thing that gave us security on earth was the certainty that he was there, invulnerable to plague and hurricane … invulnerable to time, dedicated to the messianic happiness of thinking for us, knowing that we knew that he would not take any decision for us that did not have our measure, for he had not survived everything because of his inconceivable courage or his infinite prudence but because he was the only one among us who knew the real size of our destiny.

— Gabriel Gárcia Márquez

The Autumn of the Patriarch

Autocrats and patriarchs share a fateful dilemma: once ensconced in power, and even as they exercise it and hold sway over their dominion, the countdown to their demise is on. In dynastic China, sycophants attempted to ward off the inevitable by hailing the emperor as ‘Lord of Ten Thousand Years’ 萬歲爺, and even in the Maoist era the agèd Chairman’s approaching death was spoken of in delicate terms such as ‘After One Hundred Years’ 百歲之後 or when ‘He Goes to Meet Marx’ 去見馬克思. The old materialist himself mocked the refrain constantly on the lips of his devotees — ‘Respectful Wishes that Chairman Mao Live for Ten-thousand Years Without End!’ 敬祝毛主席萬壽無疆. On 18 August 1966, he responded to one fervent well-wisher — Luo Xiaohai, one of the founders of the Red Guards — by scoffing: ‘Even ten-thousand long lives have a limit!’ 萬壽也有疆麼. (See footage of their encounter on Tiananmen in the documentary film Morning Sun.)

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to paramount power in 2012-2013, the Party has unabashedly declared that ‘Everything in China is under the direction of the Communist Party: party, state, army, civilian life and education, as are all points of the compass’ 黨政軍民學,東西南北中,黨是領導一切的. From 2013, we referred to Xi Jinping as China’s CoE or ‘Chairman of Everything’. With his further investiture as Leader for Life in October 2017, and given the Party’s monolithic self-vision we noted in late 2017 that, enjoying expanded investiture as head of the party-state-army, Xi Jinping was now nothing less than Chairman of Everything, Everywhere and Everyone.

Over the three decades from when he led the Communists to abandon their wartime guerrilla base in Yan’an in 1946 until his eventual demise at the age of eighty-three in 1976, Mao Zedong, China’s previous Chairman for Life, was the subject of tireless speculation: about his whereabouts, his health, mental state and competency. In the event, Mao’s autumnal years lasted for decades, and for all that time they were the source of rumours, gossip and flights of fancy.

The new leader’s unlimited tenure coupled with absolute titular authority means that students of China and observers of its political life will by necessity henceforth be on something of a deathwatch for Xi, as their predecessors were for Mao over four decades ago.

Rumour Mills

Political rumours 政治謠言 have featured during various crucial periods in the life of the People’s Republic. Given the Party’s control over the media and the secretive nature of its political processes, gossip and rumours have long been the stuff of informal comment on the issues of the day, and the means by which alternative accounts of Party rule circulate. For example, after the founding of the People’s Republic, when Mao called on intellectuals and others to help the Party ‘rectify its work style’ in light of criticisms of Party rule in the Eastern Bloc in 1956, many took advantage of the invitation to speak out against the secretive privileges and power of Party cadres. They were clamorously silenced and their repression has distorted public life in China ever since.

In 1966, when Red Guard rebels were first allowed to attack the Party, they identified privilege, corruption, and abuse of power as one of the greatest enemies to the revolution. During the unfolding civil war it was word of mouth and big-character posters that were the common medium employed by individuals and groups to speculate about the leaders and to denounce their enemies.

Around the time of Lin Biao’s fall in 1971, there was a campaign against political hearsay involving Jiang Qing and her famous interviews with Roxane Witke. Following Deng Xiaoping’s fall in April 1976, the ‘strange talk and odd speculation’ 奇談怪論 of July to September of the previous year, when Deng was trying to push through educational reforms, were denounced by the official media. Another period of political speculation followed shortly thereafter at the time of the Xidan Democracy Wall in 1978-1979; again, in 1988-1989, in the months prior to 4 June 1989, rumours and speculation were rife. Political gossip and official attempts to silence it have been the hallmarks of Chinese life for over six decades.

In the lead up to Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012, during the purge of Bo Xilai, rumours again were a feature of the nation’s life. So much so that, on 16 April that year, People’s Daily denied talk of a coup or that military vehicles had been deployed in the capital (See 人民日報:「軍車進京」之類謠言損害國家形象, 16 April 2012). In the days that followed, a series of denials and articles decrying the malign influence of rumour-mongering were published both in the national and local media (張賀, 人民日報: 要認清網絡謠言的社會危害, 16 April 2012).

***

In the penumbra of Chinese politics, a popular market for revelations about the inner workings of power is as bullish as ever. Chris Buckley of The New York Times has suggested a new subfield of China Studies/ China Watching: Ximiotics, one that already includes analyses of Xi’s fashion choices, posture, expression, and girth so as to divine his innermost thoughts.

And so it is that Xi Jinping’s tenure will be a source for frequent and colourful conjecture. The following essay by the Hong Kong writer and political analyst Lee Yee — Rumour Mill Beijing 北京流言橫飛 — offers a taste of what the future has in store.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

17 July 2018

***

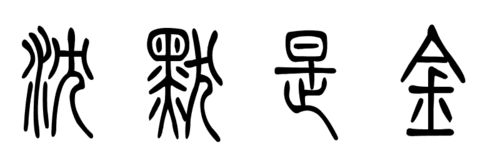

防民之口 , 甚於防川

It’s easier to damn a river

than to silence people.

— Guoyu 國語

Warring States Period

The Oldest Form of Mass Media

北京流言橫飛

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Online reports last Friday night [13 July 2018] claimed that gunfire lasting some forty minutes had been heard in the vicinity of the south-east Second Ring Road of Beijing [outside Zuo’an Men]. It was claimed that anti-Xi Jinping groups had forged a consensus to overthrow the Chairman and that dramatic events were about to unfold in the Chinese capital. Yesterday, Radio France Internationale reported that Beijing was awash in rumours, the most unbelievable of these being that [former Communist Party General Secretaries] Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao had allied with the [Jiang-era Premier] Zhu Rongji and other Party Elders who were dissatisfied with Xi Jinping’s promotion of a personality cult. They wanted to convene an Enlarged Meeting the Politburo so it could invoke the precedent of former Party Chairman Hua Guofeng [successor to Mao Zedong from 1976 to 1981] thereby allowing Xi Jinping a face-saving way of stepping down. At the same time, rumours were wildly circulating on the Internet that summed up the mood with the expression ‘Number One will rest while Ocean will take over the military’ 一號休息, 大海領軍. Of course, ‘Number One’ means Xi Jinping [in 1971, Mao’s opponents called him ‘B-52’], and ‘Ocean’ indicates Wang Yang [汪洋, whose name is part of the expression ‘Vast Ocean’ 汪洋大海]. [Politburo standing committee member] Wang Yang is perceived of as having a relatively positive image and that he is a Party leader with a reformist mindset as well as being someone who has experience in foreign affairs. 上周五晚上,有網上訊息說北京東南二環傳出槍聲,至少響了40分鐘,並指反對派已形成倒習的共識,北京將出大事。昨天法國廣播公司發出消息,指北京最近流言橫飛,最令人難以置信的一個說法稱,江澤民、胡錦濤、朱鎔基等中共元老不滿習近平大搞個人崇拜,建議召開中共中央政治局擴大會議,按照中共前主席華國鋒模式要求習近平體面下台。同時在網上瘋傳的,還有「一號休息,大海領軍」。一號當然指習近平,大海據稱指汪洋。汪洋被視為中共內部具有改革意識,有外交經驗,形象較好的人物。

Such rumours may well lack credibility, but they do offer some indication that the disharmony within China’s Party elite is increasing and, in some cases, revealing itself. The hidden eddies of opposition may gradually swell into a wave. The formulation ‘Ocean will take over the military’ is reminiscent of that surge of political gossip over two decades ago expressed using the four-character expression ‘As the Water Subsides, Stone is Revealed’ 水落石出. The stories back then spread after Deng Xiaoping had made veiled criticisms of Jiang Zemin [the Party General Secretary he had installed following the ouster of Zhao Ziyang in June 1989 and who, during 1990-1991 had allowed economic reforms to stall] during his Tour of the South in 1992. Deng didn’t mention Jiang by name, but ‘As the Water Subsides’ hinted that Jiang 江 [literally, ‘river’ or ‘river water’] would be replaced by Shi [‘Stone’ 石, Politburo member Qiao Shi’s personal name]. Although that didn’t come about, at the time there were indications of a challenge to the Party leadership and that various factors were in play. 流言儘管未必可信,但至少表示中共統治階層內部的矛盾開始尖銳化,甚至趨表面化,反對勢力從暗湧漸漸形成波浪。「大海領軍」有點像20多年前流傳的「水落石出」,那是1992年鄧小平南巡發話不點名批江澤民之後傳出的,暗指江落而由喬石替代,儘管終於未成事,但也意味着最高權力受到挑戰,權鬥出現變數。

Gunfire in Beijing might not be credible, but French media reports about rumours being rife in the Chinese capital is a matter of fact. The rumours include such things as:

- The promotion of ‘The Great Learning of Liangjiahe’ — that is, the Liangjiahe Spirit 梁家河精神 decocted from Xi Jinping’s period as a rusticated youth in Liangjiahe [from 1969 to 1975] — promoted by the Shaanxi Academy of Social Sciences grinding to a halt;

- News from the Communist Party’s Xinhua News Agency that Chairman Hua Guofeng acknowledged criticisms of his attempts to create a personality cult [following Mao’s death in September 1976];

- The video clip of a young woman by the name of Dong Qiongyao splattering a portrait of Xi Jinping with ink. Following her detention there were reports of similar incidents in other parts of China and news that the Public Security authorities had issued an urgent internal directive banning the display of portraits of Xi in public places and the removal of those that had been put up; and,

- There were accounts that, since becoming General Secretary [in November 2012] his name had featured on the front page of People’s Daily every day until, suddenly, it didn’t.

北京槍聲或未可信,但法廣提出一些迹象卻是不容否定的事實。包括陝西社科院推出把習近平當年在梁家河的知青生涯作為「大學問」研究,曾經喧嚷一時卻突然被緊急叫停;新華社轉發當年擔任黨主席的華國鋒為他默許對他的個人崇拜而認錯的信息;一位名叫董瑤瓊的青年女子向習近平畫像潑墨並在網上公開她這行動的影片,她被捕後,中國一些地區也出現了塗污習近平畫像的事,公安部門隨後內部下發不要在公共場所張貼習近平像,已張貼的也要除下的緊急通知;《人民日報》自習近平擔任總書記以來,每天頭版都有習的消息,而最近居然有一天頭版沒有了他的名字。

Such stories might not prove that there will be any dramatic developments within the Party leadership. But there may well be pushback both inside and outside the Party since the Nineteenth Party Congress when term limits were abandoned in favour of life-long tenure [for Xi], and when, thereafter, there were stirrings of a new personality cult at the same time as increased political repression in tandem with China’s more overtly aggressive stance on the international scene. It is entirely possible that in the face of China’s worsening economic situation and, confronted by a critical international environment resulting from trade war, Xi’s leadership team are taking temporary steps to modulate things. 這些迹象未必就意味着中共最高權力會出現戲劇性變動,很大可能是習近平在去年十九大取消了任期制、恢復終身制之後,開始搞個人崇拜,對內政治高壓,對外顯示霸氣,引致內外反彈,在大陸經濟形勢惡化和貿易戰導致國際形勢嚴峻的情勢下,習政權暫時採取退一步的降溫措施。

A coup d’état seems hardly on the cards, but there is evident dissatisfaction with Xi Jinping inside the Communist Party. Political repression, Internet control, popular dissatisfaction with the costs of health care and education, as well as price increases are all a reality. In situations when there are such internal and external pressures, one in which both the ruling elite and the masses are resentful yet have no way to express their displeasure, it is inevitable that the general mood finds reflection in wild rumours and heady gossip. 儘管政變發生的機會不大,但黨內對習不滿卻是事實,政治高壓、網絡嚴控,醫療、教育、物價造成民間積怨更深也是事實。在內外交困的形勢下,無論是部份掌權者還是老百姓,都有怨氣,也都無從宣洩,傳言滿天飛正反映了這樣的態勢。

When the long-term unofficial understanding that Party leaders would only serve two terms was to be abandoned at the time of the Nineteenth Party Congress in October last year, and that life-long political tenure of the kind not seen since the time of Mao’s personality cult, I observed: 去年中共十九大,打破掌最高權力者只做兩任的不成文規定,恢復個人崇拜時代的終身職,那時我已經撰文表示:

History teaches us that this will invariably lead to a disastrous contention over the political succession, not merely a struggle at court but a broader social disaster. 人類歷史的所有經驗,都證明這一定會引爆權力繼承的大災難,不僅是宮廷災難,更是社會災難。人類歷史的所有經驗,都證明這一定會引爆權力繼承的大災難,不僅是宮廷災難,更是社會災難。…

It will inevitably result in a political catastrophe on the mainland, one that won’t be delayed until there is a need for a successor in five years. The lesson that history teaches us is that such crises can unfold in the political present. 而且災難不會等到五年後需要接班時才發生,歷史提供的所有教訓都是:災難在現時政局下很快就會出現。[See Who’s on First — China’s Successive Failures, China Heritage, 20 November 2017]

Even if there are dramatic developments, there is no reason to think that they will augur well for China. There will be no sudden illumination; though, for a time at least, it might mean that a ray of light cuts through the darkness that has enveloped both the Mainland and Hong Kong. 倘若局勢有戲劇性轉變,也不能認為轉變就會為中國帶來光明。但至少會有一段時間,中國及香港,可能在暗黑中露出一線亮光。

— Lee Yee 李怡

世道人生: 北京流言橫飛

蘋果日報, 2018年7月17日

***

Note:

This essay and translation appear both in Watching China Watching and The Best China:

- Geremie R. Barmé & Lee Yee, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018 (The Best China XIII and Watching China Watching XXXI)

***

Other Essays by Lee Yee in China Heritage:

- 1 October 2017 — The Best China, China Heritage, 1 October 2017

- Lee Yee, Playing by Peking’s Rules, Asian Wall Street Journal, 11-12 July 1986

- The Ayes Have It, China Heritage, 18 October 2017

- Lee Yee, What’s New About Such Thinking? — The Best China, II, China Heritage, 5 November 2017

- Lee Yee, The Unbuilt Wall of Sorrow — on the centenary of the Russian Revolution (The Best China, III), China Heritage, 7 November 2017

- Lee Yee, Who’s on First — China’s Successive Failures (The Best China, IV), China Heritage, 20 November 2017

- Lee Yee, China Bound — meeting and eating (The Best China, V), China Heritage, 15 December 2017

- Lee Yee, Hollow Men, Wooden People (The Best China, VI), China Heritage, Christmas Eve, 2017

- Lee Yee, A Very Hong Kong Xmas (The Best China VII), China Heritage, Boxing Day, 2017

- Lee Yee, The Year 1971 (The Best China VIII), China Heritage, 28 February 2018

- Lee Yee, The Real Man of the Year of the Dog — Dog Days (III) / (The Best China IX), China Heritage, 2 March 2018

- Lee Yee, A Landscape Desolate and Bare (The Best China X), China Heritage, 12 March 2018, also included in New Sinology Jottings

- Lee Yee, My Qingming (The Best China XI), China Heritage, 10 April 2018, also included in New Sinology Jottings and Wairarapa Readings

- Lee Yee, Doubtless and Clueless at Peking University (The Best China XII), China Heritage, 8 May 2018

- Geremie R. Barmé & Lee Yee, Deathwatch for a Chairman, China Heritage, 17 July 2018 (The Best China XIII and Watching China Watching XXXI)