Translatio Imperii Sinici &

a Lesson in New Sinology

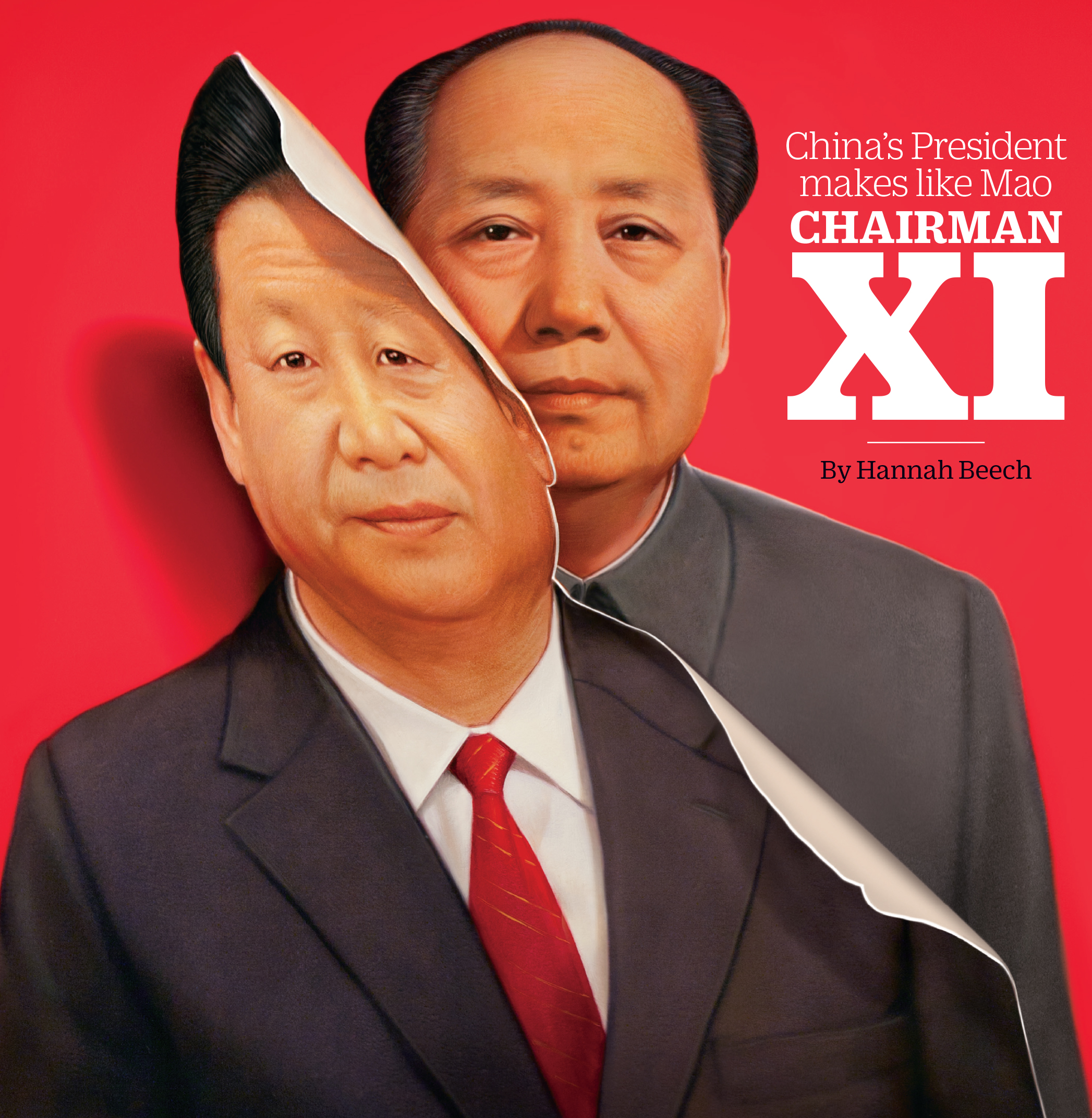

‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’ is Part II of ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’, Jianying Zha’s coruscating reflections on the legacy of the ancient thinker Han Fei and the Legalist school in Xi Jinping’s China. It follows on from Zha’s Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’ and Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, which appeared in China Heritage on 14 and 16 July 2020 respectively.

As Zha observes, it is hardly surprising that Hanfeizi 韓非子, a decoction of the pre-Qin thinker Han Fei’s advice on rulership and political manipulation:

‘…has been compared to Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. When entering the arena of practical politics, both works check morality at the door, both excel at a pure (a priori?) and high-level exploration of the art of wielding and maintaining power. If, however, there is a contest for the title of who first formulated the ways and means to pursue totalitarian political control, I’d wager that China’s Prince Han surely comes out on top.’

As contestation between the United States and China’s People’s Republic has intensified in recent years, the old ways of instant expertise — that kind of ‘pop China literacy’ that has been modish in the business world and among Western political apparatchiki, as well as media mavens cum-influencers for decades — have taken something of a ‘Sinological turn’.

Nowadays, even figures like Newt Gingrich, the odious Republican Machiavelli, and the irrepressible guru of market democracy Francis Fukuyama — offer caricatures of Emperor Qin Shihuang and China’s autocratic tradition with aplomb. As unflappable political nabobs add new chapters to the old story about the unchanging China, Jianying Zha’s ‘Han Fei philippic’ comes as a timely corrective.

***

‘China’s Heart of Darkness’ essay is presented as a ‘Lesson in New Sinology’, one of a series focussed on the kinds of ‘literary-historical-intellectual’ 文史哲 usage and allusions that are used in contemporary politics and culture. It is also a chapter in our series Translatio Imperii Sinici which is concerned with the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which still powerfully influence the Chinese world, and will continue to do so.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

16 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Xi Jinping

Part II: Mao’s Abiding Legacy

Jianying Zha 查建英

Reading Between the Lies

Politicians and leaders are influenced by the books they read. Their favorite books, or the works to which they refer, often hint at their true worldview. Texts that they regularly consult or cite are also more likely than not to be an intellectual guide to their actions. Margaret Thatcher, for example, was much taken with Friedrich Hayek. It was even said that she carried a copy of Road to Serfdom in her handbag. And every student of American history knows the books that the framers of the constitution read and discussed. Jefferson, Madison, Adams, Hamilton and Franklin probably shared a similar list of favorite authors: before arriving in the Pennsylvania State House in May 1787, they had all read Hobbes, Locke and Montesquieu. Well versed in Greek philosophy and Roman law, they could also easily relax into a conversation over tea or whisky while citing Livy and Plutarch. They were passionate believers in liberty, democracy and the rule of law; their core political values were shaped in part by the authors who had enlightened and inspired them. The echoes of Locke and Montesquieu are so loud and clear both in the Declaration of Independence and in the American Constitution that the pair could well be considered as honorary co-founding fathers.

What, then, did the founders and leaders of China’s Communist Party read? Mao Zedong, by far the best read of the Long March generation of leaders, was widely reported to be a superficial and sloppy reader of Marx. Sure, he was familiar with The Communist Manifesto, but that was little more than a pamphlet, and he may well have embarked upon Das Kapital, but indications are that he never finished it. He was, however, conversant with the Stalinist History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Short Course. Even then, he was at a distinct disadvantage during his theoretical tussles with Party dogmatists like Wang Ming 王明, a man who was not only better versed in Marxist theory but also enjoyed Soviet backing. Nonetheless, Mao was a natural and wily political infighter, he was also steeped in Chinese classics and the history of pre-Qin and dynastic statecraft. His worldview, sensibilities, strategic wiles and leadership style were, essentially, profoundly nativist. Although I’m skeptical about claims that he read Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance 資治通鑒, the multi-volume historiographical classic of the Song dynasty, seventeen times, yet on his ceaseless peregrinations outside Beijing (he would spend months every year travelling and at various ‘detached palaces’ in the provinces) he often had volumes of the tome at hand. From his speeches, comments to other Party leaders, aides and in his recommendations to comrades, it is evident that he was intimately familiar with key historical works and with what is known as ‘the art of rulership’ 帝王之術. He obsessively studied accounts of famous battles through the ages and frequently referred to actual skirmishes. Like any outstanding commander of a vast army, Mao knew everything he needed to know about winning land wars. Given New China’s original ambitions, he didn’t need to become an expert in sea warfare.

From an early age, the Chairman evinced admiration for the Legalists: he was only eighteen when he wrote an essay praising Lord Shang’s reforms. Composed in imitation of the classical style with a youthful flourish, the essay won first place in his school’s writing contest.[6] Mao’s lifelong identification with Qin Shihuang is well-known. The first emperor came from a rural backwater; he trained a highly disciplined army; and he led it through countless bloody campaigns to victory, as did Mao. In 1958, shortly after the ‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’, during which half a million men and women — mostly mild intellectual critics of Communist rule — were persecuted, Mao famously evoked the spectre of Qin Shihuang. ‘Qin Shihuang was nothing compared to us’ 秦始皇算什麼?, Mao told a meeting of the Party elite:

‘He only buried 460 scholars. We have buried forty-six thousand scholars. … I’ve debated with those in our democratic parties. “You condemn us as Qin Shihuang. But you’ve got it wrong. We have outdone him a hundredfold. You curse us for being tyrants? We never deny it. It’s a pity that your accusations fall short — invariably we have to fill in the details for you.’

他只坑了四百六十八個儒,我們坑了四萬六千個儒……我們與民主人士辯論過,「你罵我們是秦始皇,不對,我們超過了秦始皇一百倍;罵我們是秦始皇,是獨裁者,我們一概承認。可惜的是你們說的不夠,往往要我們加以補充。」(大笑)

As Mao chuckled, his audience added to the bonhomie with their own laughter.

[Note 6] Mao’s school essay, entitled ‘商鞅徙木立信论’, is the first entry in Mao Zedong’s Early Manuscripts 毛澤東早期文稿, published in 2008. Liu Qian 柳潜, Mao’s Chinese teacher, was so impressed that not only did he give the essay full marks but he lavished the prodigy with praise: ‘Given application and time, who knows what this outstanding talent may well achieve.’ 自是偉大之器,再加功候,吾不知其所至。In the hope of further contributing to his prize pupil’s intellectual development, Liu lent the young Mao a copy of the Qing-dynasty Imperial Compendium of Historical Precedents 御批歷代通鑑輯覽. Decades later, Mao told the US journalist Edgar Snow that ‘after reading the Imperial Compendium I concluded that it was best if I pursue my studies without help.’ 我讀了《御批通鑑輯錄》以後,得出結論,不如自學更好。

***

***

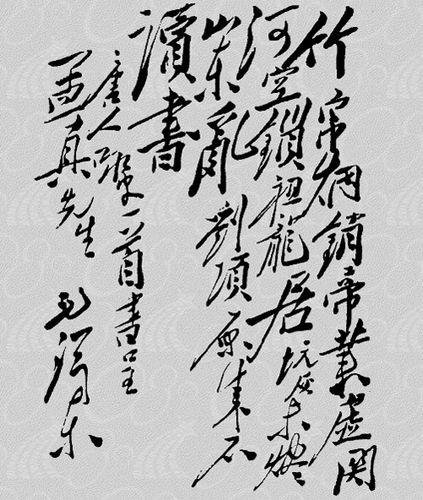

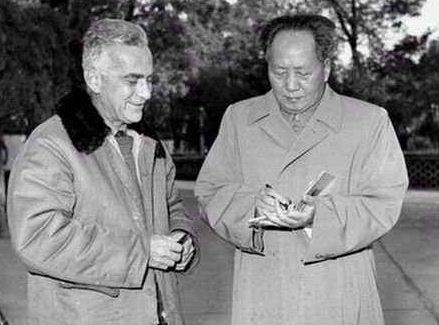

In the 1970s, incensed by reading his former ‘close comrade-in-arms and hand-picked successor’ Marshal Lin Biao’s secret diary in which Lin called him ‘a de facto Qin Shihuang’ and ‘the worst feudal tyrant in history’, the Chairman became obsessed with the topic and upped the ante in every possible way. Among other things, he composed a poem in his favourite classical style lauding the Qin emperor while ridiculing Confucius. In fact, I well remember our middle-school teachers circulating the poem so that we could collectively recite the sagacious words of the leader. To vent his vitriol further, Mao launched two successive nationwide mass political campaigns, one being the aforementioned struggle to ‘Assess Legalism and Denounce Confucianism’ 評法批儒. Indeed, at the time, he was so fixated on the subject that when receiving foreign dignitaries he invariably brought up what must have seemed to his visitors to be an arcane topic before proceeding to enlighten his puzzled guests about the great deeds of China’s first emperor. In a meeting with the visiting vice-president of Egypt Hussein el-Shafei on 23 September 1973, for example, he remarked:

‘Qin Shihuang was the first and famous emperor of feudal China. I too am a Qin Shihuang. Lin Biao vilified me for being akin to the First Emperor. There’s always been two factions in China, one that extols the First Emperor while the other decries him. I approve of the Qin emperor; I don’t approve of Confucius. That’s because Qin Shihuang was the first ruler to unify China, to standardise the writing system and to build a network of broad roads. He didn’t create a state within a state. He used authoritarian means to rule and he governed through officials dispatched from the central government. They were replaced every few years by other officials; they weren’t hereditary rulers.’

秦始皇是中國封建社會的第一個有名的皇帝,我也是秦始皇。林彪也罵我是秦始皇。中國歷來分兩派,一派講秦始皇好,一派講秦始皇壞。我贊成秦始皇,不贊成孔夫子。因為秦始皇第一個統一了中國,統一了文字,修築了寬廣的道路,不搞國中有國,而用集權制,由中央政府派人去各地,幾年一換,不用世襲制度。

[7][Note 7] See 許全興,《毛澤東晚年的理論與實踐》,中國大百科全書出版社,1993年,第451-452頁. Mao’s pro-Qin Shihuang poem — 七律 · 讀 《封建論》 呈郭老 — which was addressed to Guo Moruo 郭沫若, a noxious high-culture toady, in 1973, reads as follows:

I advise you not to criticise the Emperor of Qin,

There’s more to say about burning books and burying scholars.

The ancestral dragon may be dead but Qin lives on,

While Confucian scholarship despite its reputation is but chaff.

A hundred generations have pursued the rule of Qin…

勸君少罵秦始皇,

焚坑事業要商量。

祖龍魂死秦猶在,

孔學名高實秕糠。

百代都行秦政法…

— from, GRB, ‘For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone’.

***

***

What then about Qin Shihuang’s favorite author? Did Mao also appreciate Prince Han’s wicked intellect? Perhaps the answer lies in a remark Mao made during a conversation he had with his nephew Mao Yuanxin 毛遠新 in January 1976 at the Chairman’s ‘swimming pool residence’ at Zhongnanhai, the former imperial garden-palaces on the west flank of the Forbidden City from whence the Communists had ruled since 1949.

Mao Yuanxin had ready access to his uncle since, after studying engineering and a stint in the army he was being groomed for high office. Zhou Enlai, the premier of the Chinese state and its formal administrative head had just died and as Mao expressed an avuncular interest in the young man’s progress the Chairman’s conversation ranged over the fraught issues surrounding Zhou’s successor. In his trademark style of employing historical allusions to discuss contemporary politics, Mao offered a disquisition on the power struggle that had followed the death of Zhang Juzheng (張居正, d.1582), a famous Grand Secretary (equivalent to ‘premier’) in the court of the Ming dynasty whose controversial reforms and ‘new legalism’ had made him a polarising figure. Upon Zhang’s demise, bitter factional infighting had broken out and tens of thousands of officials became embroiled in the mêlée at court. Many died in the ensuing strife and the ruling Wanli Emperor all but lost control of the situation. Warming to his theme, Mao reminded his nephew that he had to study classical texts and learn the lessons of China’s past and in response Yuanxin reported that was precisely what he had been doing. In fact, he told his uncle, at that point he happened to be reading up on Li Si and Han Fei (Mao Yuanxin was being obsequious: at the time ‘studying’ simplified versions of Legalist texts and accounts of such historical figures was obligatory for Party members). ‘These are precisely the works you must read,’ Mao said approvingly.

‘And not just once; you must read them at least five times.’ (‘Five times’ was the stock number Mao cited when boasting about his own assiduous reading habits and enjoining studious lickspittle party leaders to emulate his habits.)

As a young man, Mao went on, he had read Hanfeizi several times. Why, he had even committed entire chapters to memory. He then offered his nephew an analysis of what really happened between the two famous disciples of Xunzi: Li Si, Mao observed, was anxious about eventually being out-maneuvered by Han Fei, so he took advantage of his superior position in the Qin court to make a preemptive strike. In other words, he had his former classmate Han Fei done away with while he still could. That’s why — and here Mao quoted from memory — Han had said fatefully:

‘Men of remote antiquity competed via morality and virtue; those of the middle ages strove after wisdom and strategy; today, men contend by force and strength.’

上古競於道德,中世逐於智謀,當今争於氣力。 — 《韓非子 · 五蠹》

‘What Han Fei meant by “force and strength” was power,’ Mao added. Then, to emphasise the point, he quoted another passage:

‘Whomsoever is possessed of magisterial strength is courted; while whomsoever has inferior strength pays court to others. It is for this reason that the shrewd ruler strives for might.’

力多則人朝,力寡則朝于人,故明君務力。 — 《韓非子 · 顯學》

‘A smart emperor must control power,’ Mao concluded.

‘[That’s why] Qin Shihuang took Han Fei’s advice and created a system of centralised authority.’

Here there was no beating about the bush; Mao was addressing a family intimate behind closed doors. He was offering his nephew the unvarnished truth sans artifice. Even though the exchange focussed on two of the best-known Legalists in history, there was no talk of ‘law’ or ‘the rule by law’. After all, law is but an instrument to be used in the service of the master, not the other way around. The only game worth the wager was about unadulterated power, pure and simple.

***

***

Legal Niceties

A genius at generating and manipulating chaos to his advantage — he took the Churchillian ‘never let a crisis go to waste’ to a new level by manufacturing crises during which he could pursue both his political vision as well as his personal ambition — Mao Zedong was brazenly contemptuous of the law and legal niceties. In 1953, in part due to pressure from Stalin, leaders of China’s Communist Party set to work on writing a constitution for the new people’s state. The relevant drafting committee consisted of high-level apparatchiki loyal to Mao and, although the process included a brief period of ‘popular consultation’ before the document was promulgated in 1954, it wasn’t long before Mao cast aside all pretense. ‘Law is something you can’t do without,’ he told at a meeting of Party leaders during the devastating Anti-Rightist Campaign, itself an extralegal purge (stage managed, we should remember, by none other than Deng Xiaoping), ‘but we have our own ways and means… . We have no need to rely on [the Constitution or laws]. For the most part, we simply govern by [Central Party Committee] resolutions and meetings, which we hold four times a year.’

Mao’s flagrant disregard for law along with his out-of-hand dismissal of anything such as an independent judiciary that might oversee the legal system, was not just merely an idiosyncratic quirk, it was a habit of mind that reflected the political realities of the day: Mao was a twentieth-century autocrat born of struggle and warfare, a man who gradually accrued unto himself — with the fawning support of his allies and a generally unwitting population — unprecedented personal power. Such a demigod doesn’t have to pretend that he respects anything so onerous as formal rules and regulations. When the situation required, the ‘law’ 法 was something that could easily be dispensed with; laws were mere documents on paper and Mao metaphorically tore them up with capricious abandon. ‘I know no law; I hold nothing sacred,’ he remarked cryptically when meeting with the sympathetic American journalist Edgar Snow in December 1970. The remark, couched in terms of a classic pun (which Snow completely misunderstood), sounded whimsical and witty, but it was a profoundly revealing admission.[8] What Mao really meant was: in China, I am Law personified. Reigning supreme by means of both 術 shù (tactics) and 勢 shì (propensity), Mao was truly an awe-inspiring ruler, one who brings to mind the mythical ‘flying-dragon’ 飛龍 fēi lóng that Han Fei described in a quotation from Master Shen Dao.[9]

***

***

[Note 8] In an essay about studying Chinese with Pierre Ryckmans/ Simon Leys in the early 1970s, Geremie Barmé noted that:

In 1970, the pro-Party American journalist Edgar Snow reported on what would be his final encounter with Mao. As he was leaving the Chairman’s book-lined study in the party-state compound of Zhongnanhai, Mao described himself as ‘only a lone monk walking the world with a leaky umbrella’ 和尚打傘 / 無髮(法)無天. In an essay written following Mao’s death in September 1976, Pierre observed that:

‘With its mixture of humorous humility and exoticism, this utterance had a tremendous impact on Western imagination, already so well attuned to the oriental glamour of the Kung Fu television series. Snow’s command of the Chinese language, even at its best, was never very fluent; some thirty-odd years spent away from China had done little to improve it, and it is no wonder that he failed to recognise in this ‘monk under an umbrella’ (heshang da san) evoked by the chairman a most popular Chinese joke. The expression, in the form of a riddle, calls for the conventional answer ‘no hair’ (since monks keep their heads shaven), ‘no sky’ (it being hidden by the umbrella) — which in turn means by homophone (wu-fa wu-tian) ‘I know no law, I hold nothing sacred.’ The blunt cynicism shown by Mao in referring to such a saying to define his basic attitude was as typical of his bold disregard for diplomatic niceties as its mistaken and sentimental adaptation by Snow is revealing of the compulsion for myth-making, of the demand for politico-religious kitsch among certain types of Western intellectual.’

— from Simon Leys, ‘Aspects of Mao Zedong’

collected in The Hall of Uselessness, p.334]

[Note 9] As Han Fei writes:

‘Shenzi said, “The flying dragon rides on the clouds and the rising serpent slithers through the mists; but as soon as the clouds disperse and the mists clear, the dragon and the serpent become the same as the earthworm and the large-winged black ant, because they have been deprived of that which they have relied. If worthies are subjugated by unworthy men, it is because their power is weak and their status is low; whereas if the unworthy men can be subjugated by the worthy, it is because the power of the latter is strong and their status is formidable. When he was still a commoner Yao [堯, a legendary sage-king extolled for his benevolence] could not even rule over three people, whereas when Jie [桀, an infamous tyrant] was the Son of Heaven he threw All-Under-Heaven into chaos.

慎子曰,飛龍乘雲,騰蛇遊霧,雲罷霧霽,而龍蛇與螾螘同矣, 則失其所乘也。賢人而詘於不肖者,則權輕位卑也;不肖而能服於賢者,則權重位尊也。 堯為匹夫,不能治三人;而桀為天子,能亂天下。

“Thus is it that I know that propensity [made possible by holding actual power] and position [within a structure of rulership] enable everything whereas mere virtue and wisdom are not worth striving for. Indeed, if the bow is weak and the arrow flies high, it is because it is buoyed by the wind; if the commands of an unworthy man are put into practice, it is only due to the support of the majority. When Yao propounded his ideas when he had no position he was ignored; but, as soon as he ‘faced south’ as Ruler of All-under-Heaven, whatever he ordered was carried out and anything that he forbade was put to an end. Thus considered, it is evident that virtue and wisdom cannot make the majority comply, yet propensity [that is, the application of power] and high position may contain even the most worthy.”

吾以此知勢位之足恃,而賢智之不足慕也。夫弩弱而矢高者,激於風也; 身不肖而令行者,得助於眾也。堯教於隸屬而民不聽,至於南面而王天下,令則行,禁則止。 由此觀之,賢智未足以服眾,而勢位足以缶賢者也。

— ‘Interrogating the Doctrine of Propensity’

《韩非子 · 難勢》, Hanfeizi, Chapter XL.

***

***

Mao died in September 1976, eight months after his conversation with his nephew. Four weeks later, some of the ‘two-faced’ high-level army and security officials in Party headquarters pounced, rounding up key figures in the ultra-radical faction previously protected by Mao, including his wife Jiang Qing 江青. Mao Yuanxin was arrested and courtmartialed, falling along with what was now dubbed the ‘Gang of Four’ in what was nothing less than a coup d’état. He spent the next seventeen years in prison. The years-long campaign about Legalism versus Confucianism came to an abrupt end, and with it another lawless period in modern Chinese history.

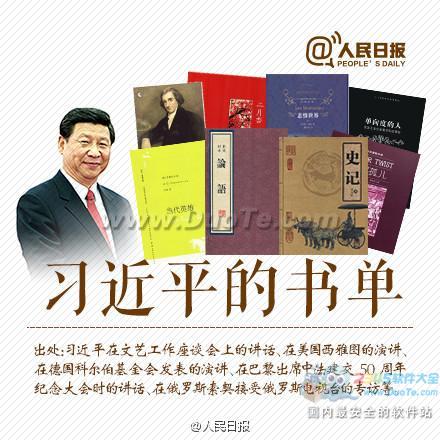

Going by the Book

Compared to his ‘spiritual mentor’ Mao Zedong, Xi Jinping is hamstrung both as a result of a charisma-deficit and also due to his lack of erudition. Be that as it may, Xi is much given to 掉書袋 diào shūdài, literally ‘dropping the satchel of books’: he loves to show off what books he has read. The party-state-army chairman needs no encouragement to rattle off lists of authors and books whether it is in his invariably ‘important speeches’, essays, encomia, inscriptions or ‘gilded bons mots‘ 金句. He never tires of claiming that the cavalcade of names represent the range of intellectual riches that have nurtured him from his earliest days. For a man who came to maturity when the education system was in a state of collapse and when most classics, not to mention works of literature were unavailable, Xi remains doggedly set on convincing people that not only was he always a voracious reader but that his dogged pursuit left him miraculously well-read. Such claims invite mockery and Chinese social media platforms bristle with contempt.

‘Xi is clearly poorly educated’, observed a learned friend of mine in Beijing. ‘He didn’t even finish middle school and now he’s just overcompensating. Risible PR like this — which is probably the work of one of his speech-writing teams, generally backfires. It’s got “inferiority complex” stamped all over it.’[10]

[Note 10] At the start of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, Xi was a thirteen-year-old middle school student. After seven years working in the countryside as a sent-down youth (during which time he became a Party cadre), he got into Tsinghua University where he studied chemical engineering. He was a ‘worker-peasant-soldier student’, so called because the highly select group got into college not on the basis of academic excellence, but for their superior class background and political performance. The practice came to an end when college entrance exams were reinstated in 1977.

From 1998 to 2002, while holding the full-time post of vice governor and then governor of Fujian province, Xi was formally enrolled in a course of Marxist theory and ideology, again at Tsinghua, some two thousand kilometers from his day job in Fuzhou. He graduated with a ‘doctorate in law’.

This remark, typical of Xi’s critics — whose number is legion — may be true as far as it goes, but I tend to think that they have seriously underestimated the New Age Chairman’s devotion to such extracurricular pursuits as reading. ‘Reading has always been a way of life for me’, Xi told a reporter for Russian TV at the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014. In other interviews and speeches he has repeatedly remarked that: ’When I’m not working, my main hobby is reading’. This is quite possibly true.

If so, it is worth considering what books have made the deepest and most crucial impact on his thinking. The Federalist Papers appears in one of his voluminous reading lists, although it was pointedly included in a list released during a visit to the United States. But what does that mean? Moreover, what do the long and varied lists tell us overall? Are they anything more than examples of diplomatic name-dropping, a vacant flourish tailor-made for each occasion? After all, landing in Moscow, Russian greats trip off his tongue; dining in Paris, French masters grace his banquet remarks. When, in 2014, Xi convened a ‘Forum on Literature and the Arts’ in Beijing he addressed a select audience of prominent writers and artists — including the Nobel Laureate Mo Yan 莫言. On that occasion our bookish strongman managed to best his own not-inconsiderable record by mentioning no fewer than 136 authors along with a mini-library of famous Chinese and Western novels. He wasn’t merely aiming to impress a captive audience. After all, no one was in any doubt about the real point of the forum: the learned Red Ruler was postulating guidelines for the edification and instruction of all Chinese writers and artists — he was teaching the educators.

***

***

Shortly after the forum, I met with a friend who had known Xi when they were both ‘rusticated youths’ living in the same region in Shaanxi province in the early 1970s. According to official media reports, at the time the villagers had immediately been impressed by the princeling from Beijing who had turned up with a suitcase full of books. Subsequently, Xi reportedly entertained anyone who visited his modest 窯洞 yáodòng (a local style cave-dwelling) with stories gleaned from such classical novels such as The Three Kingdoms and The Water Margin (also known as All Men Are Brothers).

My friend, whom I’ll call Ruyi, confirmed that Xi was indeed a diligent reader. ‘But the books he read were particular’, he told me:

‘People from intellectual families like me would read and share any Western work we could get our hands on. For example, we loved Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and Romain Rolland’s Jean-Christophe. But Xi Jinping was absorbed in old Chinese books and classics.’

Ruyi couldn’t recall which ones exactly; the two hadn’t been particularly close then and they haven’t been in touch since. Decades have passed and, having left China in the late 1980s, Ruyi now lives in California.

Meanwhile, Xi Jinping’s penchant for quoting classical texts has long been on display — starting with his stint as Party Secretary of Zhejiang province from 2002 to 2007 when a fortnightly column titled ‘New Words for the River Zhi’ 之江新語 (a sideways reference to A New Account of the Tales of the World 世說新語, a famous collection of humorous anecdotes from the fifth century CE) appeared under his name in the local press. What may well be a worthy youthful old habit of reading has become something of an addictive form of ‘learned virtue signalling’ that characterises his tireless speechifying as the head of China’s party-state-army. It is here, I believe, that we may detect a hint of the cultural and historical underpinnings of some of Xi Jinping’s most deeply held views and political motivations

Locus Classicus

In 2015, People’s Daily Press published a book titled Xi Jinping Cites the Classics 習近平用典. The book’s editors had combed through Xi’s speeches, writings and bons mots to compile a partial list of 135 citations (another Xi acolyte trawling through material from the same period tallied over 300 references; it is an ever-expanding bibliography). State media promoted the book as demonstrating Chairman Xi’s vast wisdom and profound erudition and the volume was distributed to Party members for in-depth study, as well as to government officials and others who were preparing for civil-service examinations. The appearance of such a tome is significant in its own right since it is yet another reflection of the cult of personality being engineered with Xi’s acquiescence. On the back of this made-to-order publishing phenomenon, Yang Lixin 杨立新, one of the editors of the collection, did some further finagling to concoct a Top Ten list, that is ‘works most frequently cited [by the Leader], as well as the most consequential which best reflect His ideas about governance.’

Two of the quotations in the Top Ten are from Hanfeizi. The first reads:

‘No country is permanently strong, nor is any country permanently weak. If those who impose The Law 法 fǎ are strong, the country will be strong; if they are weak, the country will be weak.’

國無常强,無常弱。奉法者强則國强,奉法者弱則國弱。—《韓非子 · 有度 》

Of particular significance are the various occasions on which Xi employed this line from Han Fei. He used it four times during 2014, a crucial year for the consolidation of his rule. They were:

- On 17 February, at a central symposium on the theme of ‘deepening reforms’ attended by provincial heads and government ministers;

- On 30 April, at the end of a tour of inspection of Xinjiang, a hotspot of ethnic conflict;

- On 5 September, on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the promulgation of the 1954 Constitution hosted by the National People’s Congress; and,

- On 23 October, at the Fourth Plenum of the Eighteenth Central Committee of the Communist Party.

In each case, Xi vowed to ‘strengthen the rule of law’ and ‘govern according to the constitution’, themes that he has repeatedly showcased as being central to his administration. In fact, during his first years in power (2013-2014), Xi repeatedly advertised his long-term intentions via winsome metaphorical formulations: ‘constrain power within the cage of the governance system’; ‘ensure that power operates in the sun [that is out in the open]’; ‘enhance restrictions on and the oversight of power’; and, ‘no organisation or individual is above the Constitution and the law’. Such catchphrases were repeated ad nauseam in the official media and the reaction of the public, as far as ‘public opinion’ can be gauged in the People’s Republic, generally appeared to be positive. Even many liberal intellectuals harboured a hope that statements such as these presaged the possibility of positive change in the future. After all, large swathes of the population had long grown weary of the egregious abuses of power and the endemic corruption of the system and they took Xi’s signaling as an indication of a serious commitment to meaningful legal reform. Some local activists even speculated that a ‘Sunshine Policy’ — a law requiring public officials to divulge their assets — might even be in the offing.[11] Of course, in the same breath Xi also spoke about the importance of Party leadership, but since leaders had frequently mouthed similar sentiments, often in a pro forma fashion, in the past, the familiar drone didn’t set off any alarms, at least not at first. As for the reference to Han Fei, nobody paid it the slightest attention.

[Note 11] Xu Zhiyong 許志永, is a case in point, as are other members of the New Citizen Movement中國新公民運動. Some responded to Xi’s highfalutin statements by taking to the streets to call publicly for a new registrar of assets. They ended up in prison. Xu served a four years sentence for ‘gathering crowds to disturb public order’. He was detained again in February 2020 for continued pro-reform activities and formally arrested in June 2020 on nebulous charges.

Now let’s examine four actions Xi Jinping took while he quoted Han Fei.

One: On 29 July 2014, Xinhua News Agency suddenly announced an internal party investigation against Zhou Yongkang 周永康, a former member of the ruling Politburo Standing Committee. Having been found guilty of corruption, Zhou was subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment. It was a particularly harsh punishment for the highest official to be arraigned in court since the trial of members of the Lin Biao Clique and Gang of Four in 1980. As the country’s longtime security tsar and capo of what was known as the ‘Petroleum Mafia’ 石油幫, which had a strangle-hold over the oil market, Zhou and the sizable faction of which he was the leading patron, was a powerful and potentially threatening force. Despite the considerable public interest in the case, the investigation into activities of the ‘Zhou Clan’ 周永康集團, as it was known, was shrouded in secrecy. A shadowy task force reported directly to Xi and, apart from the final formulaic public trial, the process was to all intents and purposes extrajudicial. A draconian and shrewdly selective anti-corruption campaign ensued under the direction of Xi’s hitman Wang Qishan 王歧山 and it was surgically targeted at Xi’s political nemeses while aiding and abetting the consolidation of his authority and garnering plaudits from the less-than-well-informed populace.

***

***

Two: In Xinjiang, internment camps were being furtively constructed. Over one million Uyghurs, perceived as potential terrorists, were eventually locked up and subjected to patriotic thought remoulding. It was essentially a forced conversion program masquerading as vocational training. According to leaked internal documents, this ongoing hardline policy was instituted following Xi’s inspection tour of the region in April 2014.[12]

[Note 12] For details, see Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, ‘The Xinjiang Papers: Absolutely No Mercy’,The New York Times, 16 November 2019.

Three: On 9 July 2015, police conducted a crackdown in twenty-three provinces during which some two hundred civil rights lawyers and NGO activists were detained. A nationwide chill spread among people who identified with the liberal community of thinkers, educators, activists and journalists. Speaking venues, publishing houses, television talk-shows, Internet platforms, semi-independent salons were shut down, purged, muzzled or suspended. Scholars, critics, bloggers, activists, alternative artists, dissidents were variously censored, punished, harassed and jailed.

Meanwhile, the Party further ramped up its near universal presence by reasserting control in all spheres of life under a Mao era slogan from the early 1970s. The media was told that it had only ‘One Surname’ and a ‘Single Allegiance’ — ‘The Party’ 黨媒姓黨. Scrambling to fall into line, all the media platforms expanded ‘red culture’ programs and promoted the official ‘China Story’ and nationalism, not to mention the boundless virtues of the sagacious Xi Jinping.

***

***

Four: In March 2018, a large piece of the puzzle fell into the place. The National People’s Congress amended the Constitution when deputies ‘voted’ nearly unanimously to reverse two key constitutional provisions from the early 1980s aimed at preventing another one-man regime like that of the late Maoist era: presidential term limits were abandoned and a Cultural Revolution-era formulation about the supremacy of Communist Party leadership was reinserted into Article One of the General Principles, that is: ‘The leadership of the Chinese Communist Party is the most essential feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics’ 中國共產黨領導是中國特色社會主義最本質的特徵.

‘Outdated laws’ were thus ‘deeply reformed’ in a manner that better suited the requirements of what was now hailed as ‘The New Era of Xi Jinping’ and Xi Thought.

***

***

End of Part II: Mao’s Abiding Legacy

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’, 22 July 2020