The Best China XVI

Jin Yong’s fictional world was enthralling. Although I first encountered the work of Louis Cha (查良鏞, 1924-2018), better known as Jin Yong 金庸, in the late 1970s, the first martial arts novel of his that I read — The Deer and the Cauldron 鹿鼎記 — was his last (it appeared between 1969 and 1972). Most of my colleagues at Cosmos Books/ The Seventies Monthly in Causeway Bay, where I worked from 1977 to 1979, had been enjoying Jin Yong’s novels since their teenage years. Even before I moved to Hong Kong after three years as a student on the Mainland, I’d been aware of Ming Pao 明報, the newspaper and literary journal that Louis Cha co-founded with Shen Pao Sing 沈寶新 (the paper in 1959, the journal in 1966). During my undergraduate studies in Canberra, our lecturer, Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), had used essays from Ming Pao as reading material in our third-year course.

But, in the late 1970s, for its employees Cosmos Books 天地圖書 was a unique kind of library, and it boasted a full range of up-to-date books and translations from Taiwan, the Mainland and Hong Kong. I was absorbed in catching up on ‘serious literature’ by prominent writers of the Qing and Republican periods rather than pursuing what was, in essence, local pulp fiction. My colleagues, who, like me, were mostly in their early twenties, still insisted that Jin Yong was essential reading for anyone interested in Hong Kong and Chinese culture. Despite my early reluctance, I did appreciate that as a journalist, editor and political commentator working under the relatively benign conditions vouchsafed by the distant rule of Great Britain, Jin Yong had survived years of murderous threats and bitter attacks from Hong Kong’s ‘leftist-patriots’. For years he had been shrilly denounced his ‘anti-Communist, anti-Chinese’ 反共反華 stance and and for being ‘pro-British and a Yankee-lover’ 親英崇美. As Lee Yee 李怡 — the editor of The Seventies and my boss at the time — points out below, the late 1970s was when Jin Yong’s fame as an independent commentator on China had reached its zenith.

In 1980, back in Australia and undertaking an intensive course in Japanese (a special program that squeezed three years of language learning into one) and tutoring in Chinese during lunch breaks, suddenly I found Jin Yong’s easy-reading fiction appealing. At night, after having dealt with the drudgery of language homework and course preparation, the raffish adventures of Wei Xiaobao 韋小寶, or Trinket, in The Deer and the Cauldron, Jin Yong’s picaresque Meisterwerk were a wonderful relief. As one commentator observed after the ban on Jin Yong’s work was lifted on the Mainland, the novels were popular with the intelligentsia (not to mention workers and farmers):

In the great dramas of kungfu novels, they can find a passionate release, even if the actual fighting is fairly meaningless. … The heroes of these novels do not have to worry about distinguishing good from bad, nor do they care one whit for convention, propriety, or the law; the do what they feel like, have no regrets and no complaints. Although they endure incredible hardships, in the end poetic justice is always theirs. This clearly gives intellectuals who are totally powerless to extricate themselves from the Way of the Golden Mean a certain kind of spiritual comfort.

—from The Apotheosis of the Liumang, in Geremie R. Barmé

In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture, New York, 1999, p.83

Later in 1980, over dinner one night, I shared my response to reading Jin Yong with Pierre. He was, as always, kindly and indulgent about my reading passions, although his wife, Han-fang, in a what I would come to realise was a default mode of wanting to have the last word first, spluttered her disapproval. That night, the Ryckmans had also invited two new acquaintances to the meal — John Minford, and his wife Rachel May. John was far more positive about my youthful enthusiasm (I was twenty-six at the time). Subsequently, I would learn that Liu Ts’un-yan (柳存仁, 1917-2009), my classical Chinese teacher in Canberra, was an old friend of Jin Yong. In the 1950s, Liu had offered the budding novelist ideas about adding European panache to the Chinese tradition of martial arts fiction.

I would enjoy Jin Yong’s labyrinthine and rambling tales for a few more years until I tired of the repetitive and prolix style, the lack of character development and the endlessly bloody, and often ridiculous, sword play that put a tad too much martial in martial arts fiction for my taste. I also found the ethical world of Jin Yong’s heroes to be as wrong-headed as that of the Communist Party martyrs touted on the Chinese Mainland.

In 1989, Louis Cha famously expressed outrage following the Beijing Massacre of 4 June and, in 1993, thanks to John Minford who was in the process of translating The Deer and the Cauldron with David Hawkes, I met Cha over a lavish meal when he visited Sydney. John had persuaded the writer to fund an initial publication of two chapters of the novel, and they appeared as a special offprint of East Asian History, an academic journal of which I was the editor, and in the journal itself.

I was in awe of the famous novelist and once-notorious anti-Communist. That night, he proved to be approachable and loquacious. I was flattered when, presumably out of politeness, he complemented me on the Chinese essays I had written from the late 1970s for Ta Kung Pao 大公報 — his original journalistic home — as well as the cultural commentaries I had been publishing with Lee Yee in The Nineties Monthly since 1985. He also seemed particularly pleased to meet my boyfriend, Kong Yongqian 孔永謙, a Beijing artist who had enjoyed fifteen minutes of fame for the ironic T-shirts he designed in 1991 (see ‘Consuming T-Shirts in Beijing’ in In the Red, pp.145-178).

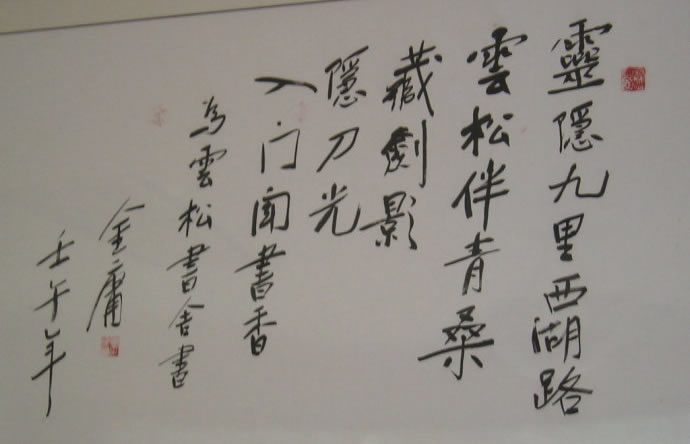

That was a rare moment: having been received by Party head Jiang Zemin earlier that year, Cha had only recently begun his reconciliation with Beijing, and it was not until the following year that he completely withdrew from his involvement with Ming Pao. As his friendship with Jiang Zemin blossomed, he would be given a prime site on West Lake in Hangzhou where he built a vanity project — a lavish museum cum-retreat that celebrated his martial arts novels. The Studio of Clouds and Pines 雲松書舍 was soon festooned with signs of Communist Party largesse. (Cha later presented it to the local government; it is now a private club.)

It was also some years before Cha began making increasingly pro-Mainland statements of the kind described by Lee Yee below, and it was long before my friend, the Beijing-based novelist Wang Shuo 王朔, launched an amusing salvo aimed squarely at Jin Yong’s literary achievement, to which the fleet-footed master responded in kind. For some readers, there was a measure of irony in the fact that some of Wang Shuo’s most famous liumang-esque 流氓, or hooligan-like, characters were powerfully reminiscent of one of Jin’s most celebrated inventions: Wei Xiaobao (aka Trinket), in The Deer and the Cauldron. Both writers had, it seemed, touched on something quintessential in their creations.

***

In August 1975, Mao Zedong made a comment on the novel All Men Are Brothers 水滸傳, a famous pre-cursor to modern martial arts fiction, and the first classic Chinese novel that I read — my university class at Liaoning University in Shenyang was, like students and people throughout China, swept up in the aftereffects of Mao’s appraisal of the book:

The useful thing about All Men Are Brothers is that it’s about people surrendering to the power-holders. It can be used as a negative example, one that teaches the people what defeatism looks like. The crux of the matter is that [the heroes depicted in] All Men Are Brothers only oppose rotten officials, they don’t rebel against the Emperor himself.

《水滸》這部書,好就好在投降。做反面教材,使人民都知道投降派。《水滸》只反貪官,不反皇帝。

Mao’s remark was used to launch a political campaign that targeted Deng Xiaoping, who was increasingly powerful in Beijing as he attempted to reform the educational system and restore prestige to the sciences. Deng was denounced by bureaucratic opponents (later named as the ‘Gang of Four’) for being a ‘capitulationist’ 投降派 and a revisionist, that is someone who was selling out the ideals of the Cultural Revolution to serve bourgeois interests. After Mao’s death, Deng would resurface to become China’s ‘paramount leader’.

Jin Yong may have crafted a fictional world inhabited by quixotic individuals pursuing heroic adventures, but, at its core it is a world that affirms power, privilege and prestige. Jin Yong’s family — the Zha lineage of Haining 海寧查氏 — part of the literary-bureaucratic establishment under the Qing dynasty, wealthy under the Republic, repressed by the People’s Republic (Louis Cha’s father, Zha Shuqing, 查樞卿, 1897-1951, was executed by the Communists as a noxious landlord, and ‘rehabilitated’ only after Deng and Jin Yong met in 1981), finally achieved redemption in the new post-Maoist Chinese order, in particular in recognition of Cha’s wealth, influence and political change of heart. It is unremarkable, therefore, that Deng and Cha eventually found much to admire in each other.

***

In The Best China we introduced readers to essays, literary works and art produced in Hong Kong. The veteran journalist Lee Yee 李怡 (李秉堯) was the founding editor of The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊 (later renamed The Nineties Monthly). He has been a prominent commentator on Chinese, Hong Kong and Taiwan politics, as well as the global scene, for over forty-five years. His position has gone from that of being a sympathetic interlocutor with the People’s Republic in the late 1970s to that of outspoken rebel and man of conscience from the early 1980s. For decades Lee has analysed Hong Kong politics and society with a clarity of vision, and in a clarion voice, rare among the territory’s writers. The essays by Lee Yee translated in ‘The Best China’ are from ‘Ways of the World’ 世道人生, the regular column he writes for Apple Daily 蘋果日報.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

5 November 2018

***

Deng Xiaoping is possessed both of daring and of vision. We admire him for pursuing a policy of reform and economic openness that is overturning the unreasonable system of the past. A true hero is not necessarily the man who conquers the Mountains and Rivers; a true hero proves himself by improving people’s lives.

— Louis Cha in Ming Pao

鄧小平有魄力,有遠見,在中國推行改革開放路線,推翻了以前不合理的制度,令人佩服。真正的英雄,並不取決於他打下多少江山,而要看他能不能為百姓帶來幸福。

— 查良鏞

(From 賴晨, 揭秘: 1981年鄧小平會見金庸都說了啥?, 人民網, 2012年02月24日)

Jin Yong & Me

金庸與我

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

It is only proper that the recently departed are accorded due respect. A writer famed throughout the Chinese-speaking world has passed away, and over the last few days Hong Kong has been awash in eulogies. Everyone is jostling to have their say — people from various backgrounds who actually knew him, those who did not, as well as others who boast a recent acquaintance. Initially, I had no desire to join the fray, but yesterday a young friend by the name of Nora sent me an article by the internet essayist Lewis Loud 盧斯達. [See: 金庸求做穩建制派的一生; and, 盧斯達, 金庸的中國體系 為華人創造了異於現實的「故國」]

Nora asked, ‘Wasn’t Jin Yong a friend of yours? Forgive me for sharing this article with you, but it gave me pause. Until now, I didn’t known about any of the things that are mentioned here; if true, it would seem that the choices Jin Yong made at various stages in his life are exactly the opposite of yours.’ 死者為大。一位蜚聲華人世界的名作家之逝,這兩天可說頌揚之聲響徹香江,各類相識的、不相識的或近年才攀關係的,都發聲了。我本不擬再湊熱鬧,但昨天年輕朋友Nora轉來網絡年輕作家盧斯達一篇文章,Nora附言說:「金庸先生和你是好友嗎?希望不要介意我share這篇文章,今天看完後反思良多。我事前都不清楚這些事,如果屬實的話,我覺得他在不同階段選的路,好像是你的完全相反。」

I read the essay and wrote back to Nora: ‘We knew each other for many years. Of course, I know much more about the various matters discussed by Loud. But your observation is correct: his choices and mine were the opposite of each other.’ She responded: ‘It’s such a pity that others — in particular younger people — always touch on these things when discussing a man possessed of such exceptional talent. If only he’d steered clear of politics and simply could have been satisfied as writer.’ 我看了這篇文章,並回覆她:「算是認識很久。盧斯達說的都是事實,我了解更多。你的想法也恰當。」她再覆我:「我覺得真是可惜呢,這麼有才華的人,後世(特別是年輕人)提到他時總避不了要提起這些觀點,他一路寫作遠離政治就好了。」

Launching into his evaluation of Jin Yong, Louis Loud observed that: ‘It is inevitable that a talented man who enjoyed extraordinary fame and was a major figure in the media world would inevitably be embroiled in politics. Many celebrated literary and academic figures simply can’t help themselves, they also yearn, one way or another, to leave their mark in the political arena.’ Loud then goes on to describe the conservative [pro-Communist] turn that Jin Yong took after meeting Deng Xiaoping in 1981 [when, among other things, Deng said that he was a fan of Jin Yong’s novels]. In particular, he mentions Jin Yong’s 1999 statement that: ‘The main duty of journalists is, like that of the People’s Liberation Army, to follow the directions of the Party and the State.’ 盧斯達的文章開頭說:「才子聲名鵲起,又涉身於傳媒,政治自然就會找上門。很多文藝菁英或學術翹楚,最終都無法守住,半推半就或者一心求政治的事功。」接下來就講到金庸在1981年與鄧小平見面後的保守言行,其中特別提到他1999年所說的:「新聞工作者的首要任務,同解放軍一樣,也是聽黨與政府的指揮。」

Although we knew each other for many decades, Jin Yong and I had very little direct contact. He did, nonetheless, have a considerable impact on me. During my high-school years, I devotedly read the movie column he wrote under the penname Yao Fulan. His writing was simply enticing — both a pleasure to read and brimming with ideas. Later, I was a constant reader of his column in Ta Kung Pao as Yao Jiayi, and I devoured his martial arts work as it appeared in installments in the press. Later, I enjoyed the editorials he wrote for Ming Pao [the newspaper he founded in 1959]. My own Chinese also benefitted considerably from his accessible and fluent style. Apart from all of that, the first wave of Cantonese-language film adaptations of his novels [from 1958] were produced by the Emei Film Company under the aegis [of the director] Lee Fa [李化, 1909-1975], my father. He did so with my encouragement. 我同金庸認識數十年,雖交往甚少,受他的影響卻甚多。中學時期就讀他以姚馥蘭筆名寫的「影話」專欄,溫馨好看又知識豐厚,其後讀他以姚嘉衣筆名在《大公報》的專欄,追讀他在報上的武俠小說連載,看《明報》社評。我的中文基礎,從他的通俗流暢充滿文字魅力的文章中得益不淺。他的作品改編電影的第一波粵語片熱潮,是我建議我父親李化的峨嵋公司開始的。

[From the late 1950s through to the 1970s] The news coverage of [Mainland politics in] Ming Pao and Jin Yong’s editorials flew directly in the face of the leftist media [in Hong Kong, controlled by Beijing]. During the refugee crisis of the early 1960s [when Mainlanders flooded into Hong Kong due to the deprivations created by the Great Leap Forward], then [in Jin Yong’s famous media clash with the Communist foreign minister Chen Yi in late 1963 over] ‘You’d Rather Have the Bomb, Than Clothe Your People Adequately’, and in particular during the Cultural Revolution and the 1967 Leftist Riots. As a leftist myself, I opposed him and I got involved in the debates, although his arguments were always more persuasive. In fact, I remember discussing things with an independently minded editor at [the Communist-controlled] Ta Kung Pao at the time: we agreed that Jin Yong’s pen was far mightier than the swords of a whole army. 60年代在難民潮、「寧要核子,不要褲子」的中共國策,特別是文革和67暴動中,《明報》的報道和金庸的社評,與當時的左派輿論是對立的。我站在他的對立面,稍稍參與論戰,但他的文章顯然更有說服力。我當時與《大公報》有獨立思想的編輯私下談論,也覺得他以一人之筆,可以說是橫掃千軍。

Jin Yong’s 1981 audience with Deng Xiaoping marked his embrace of the Communists. As things turned out, it was the same year that I cut myself asunder from the Party. [From its founding in 1970 until 1981, The Seventies Monthly, the journal Lee Yee edited, and for which I worked for from 1977 to 1980, operated under the aegis of the Beijing-controlled media establishment of Hong Kong. — trans]. Once more, I found that we were moving in opposite directions. However, subsequently, Jin Yong wrote some powerful editorials against Hong Kong reverting to the control of Beijing, that was at least right up until the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration [on 19 December 1984]. The following year, he accepted an invitation to join the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee. I well remember the essay he wrote following his first trip to Beijing as a member of that committee – ‘Casual Remarks on Drafting’ – in which he said words to the effect that: after 1997, as long as Hong Kong continues to enjoy the rule of law and its present freedoms, everything will turn out just fine. Democracy is unnecessary, in fact it would be harmful. Was this the message he agreed to convey up in Beijing? I wrote a riposte for Sun Pao in which I said: the rule of law and the basic freedoms of Hong Kong are underwritten by the democratic system of Great Britain; when Hong Kong’s sovereignty is vested in a country that is not democratic [that is, the People’s Republic of China], how can there be any assurance that the territory will be able to maintain its freedoms or the rule of law? Although Jin Yong didn’t respond directly, he got in touch out of the blue and invited me to write a regular column for Ming Pao. I declined. From then until he withdrew entirely from Ming Pao [on 1 January 1994] democracy simply was not on Jin Yong’s agenda. My views were consistently at loggerheads with his opinions, although that did not affect our friendly exchanges whenever we encountered each other. 1981年與鄧小平會見,是金庸在政治上向中共回歸,而我正是那一年與中共關係割離。二人走了相反的路。其後他在反對香港回歸中國的問題上,寫的社評還是很有份量的。直到中英簽署了《聯合聲明》。次年,他受邀參加中共的《基本法》起草委員會。記得他第一次去北京開會後回港,寫了「參草漫談」,大意是:香港97後只要維持法治、自由就好,民主非必要且有害。這是否他從北京得到的訊息?我在《信報》回應,大意是:香港的法治自由,是源於宗主國英國的民主的保障;97後換了沒有民主的宗主國,香港的法治自由如何保障?金庸沒有回應,卻突然邀我為《明報》寫專欄。我婉拒。從那時起,到他退出《明報》後的言論,民主都不是他的選項。我的評論一直與他意見相左,但無礙見面仍是朋友。

Jin Yong’s realignment, something that led him to accord with Mainland Chinese politics, left many people shaking their heads. They did so in response to such things as the ‘Double Cha Proposal’ [that favored a post-1997 arrangement whereby the executive officer of the new Special Administrative Zone of Hong Kong would be selected without universal suffrage] and his ‘Paean to the PLA’ [in 1999 when he extolled the PLA despite having quit the Basic Law Drafting Committee following the Beijing Massacre of 4 June 1989].

His about-face also had a great impact on the second half of my life, that’s because no matter how skillful a writer he was, I felt that he should have maintained the stance of an independent political critic; he was ill-suited to being directly involved in politics. I believe there’s a lesson here: clueless intellectuals should steer clear of the Soy-sauce Vat of Politics [that blackens everything that falls into it]. As for running media enterprises, because you are enmeshed in politics you end up turning a public good into something for private gain, and in the process you betray basic media ethics. I have steadfastly refused all political approaches; I choose to maintain a healthy distance from politics. I remain skeptical of power-holders. Jin Yong’s example helped inspire my own self-awareness. 金庸回歸中國政治後的轉變,太多讓人皺眉的事,「雙查方案」、「解放軍頌」只是其中一二。他的轉變對我後半生的影響也很大。因為我看到,一個寫一手好文章的人,論政就好了,參政真是不適宜,政治醬缸不是給書生們混的。至於辦傳媒,因參政而讓媒體這公器變成私用,亦有違媒體道德。我多次拒絕「政治找上門」的機會,永遠選擇與政治權力保持距離,並永遠採取對權力置疑的理念。這不能不說是從金庸的行事帶來的警覺。

— Lee Yee 李怡, 世道人生:金庸與我

蘋果日報, 2018年11月2日

Further Reading

- John Minford, Louis Cha’s The Deer and the Cauldron in English (The Best China XV), China Heritage, 16 October 2018

- The Deer and the Cauldron — Two Chapters from a Novel by Louis Cha, translated by John Minford, East Asian History, No.5 (June 1993): 1-100