鹿鼎記

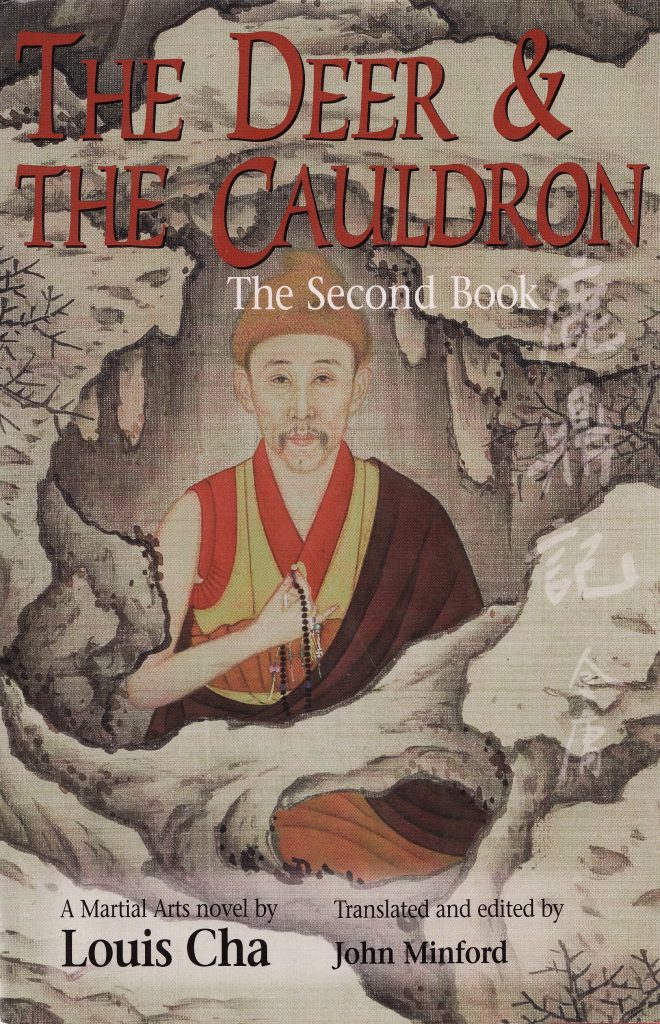

The Deer & the Cauldron, the last in a series of martial arts novels by Louis Cha (Cha Leung-yung 查良鏞, 1924-), is regarded by many readers as his best. Between 1997 and 2002, John Minford brought out a three-volume translation of the novel with Oxford University Press Hong Kong (OUP HK). Now OUP UK has published it in the United Kingdom.

This essay is the latest in our series The Best China, as well as being a contribution to our work on Nouvelle Chinoiserie.

— Geremie R. Barmé

China Heritage

16 October 2018

The Deer and the Cauldron was written between 1969 and 1972, and was the last of the long and enormously popular series of martial arts novels written by Louis Cha, or Jin Yong as he known in Mandarin Chinese, Gam Yong in Cantonese, a prominent Hong Kong public figure, millionaire, charismatic story-teller and icon of Chinese popular culture, who built his media empire on the runaway popularity of the early serialisation of his novels. Cha, born in 1924 into an old and distinguished family from Ningbo in central China, is the acknowledged modern master of the uniquely Chinese genre known as martial arts fiction 武俠小說, which has its roots in a grand old picaresque tradition going back in China to the tenth century and earlier, a medieval genre that included such masterpieces as the classic outlaw novel All Men Are Brothers 水滸傳, otherwise known as Outlaws of The Marsh, still popular with Chinese readers today.

A complete set of Cha’s novels runs to thirty-six volumes, and in their original language they have sold hundreds of millions of copies throughout the Chinese-speaking world and have been adapted into countless movies, cartoons, operas, TV-series and video games. For a long time banned as decadent and frivolous in Mainland China, for the past 30 years or so they have become enormously popular with Mainland readers too, and were among the favourite reading matter of statesmen such as paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平, 1904-1997) and Jiang Zemin (江澤民 born 1926, President of China 1993-2003, a personal friend of Cha’s). His addictive story-telling style, combining fluent traditional Chinese prose narrative with a vividly modern cinematic touch, his fertile imagination and magical ability to transform Chinese history and culture into swash-buckling romance, together with his prodigious output over the years, have often caused him to be compared to the great Alexandre Dumas père, prolific author of The Three Musketeers and many other historical romances. Cha’s own Western name, Louis, was inspired by his admiration for that other great story-teller Robert Louis Stevenson.

Cha laces his own stories with frequent references to the supernatural, and to Chinese martial arts practices, gripping his readers with action-packed scenes involving complex and sometimes extreme kungfu moves. He creates endlessly evolving and intricate plots, packed with intrigue, and always keeps his Chinese readers craving more, longing for the next instalment. He has inherited the role of the old-style street performer in the Chinese marketplace, and built his considerable fortune on his instinctive skill as a popular storyteller.

The Deer and the Cauldron, which itself has been more than once compared to The Three Musketeers, is his most mischievous, and in many ways his least typical work. But it is still unmistakably and authentically Cha, a Chinese banquet, not a take-away. Through his stories, Cha joyfully reaffirms an essential feeling of Chinese cultural identity. He creates in his readers a Chinese cultural euphoria. Beneath the excitement and humour of his stories, beneath the derring-do and the endless permutations of kungfu, lies a rich imaginative world. As one Mainland critic has put it: ‘Louis Cha’s wit and humour are based on the inner realm of Buddhist and Taoist philosophy. Behind the clownish, fool-like exterior lies a great subtlety and refinement.’

But The Deer and the Cauldron is above all a wonderful romp. In many ways it brings to mind the spoof-historical novels of George Macdonald Fraser (1925-2008), which feature that archetypal cad Flashman. It is closer to works such as Flashman and the Dragon, or Flashman in the Great Game, than it is to the old-fashioned romances of Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas.

The plot of The Deer and the Cauldron is set in the mid-seventeenth century, shortly after the Manchu conquest of China, during the reign of the second, and perhaps greatest, Manchu Emperor, known by the reign-title Kangxi 康熙, sometimes referred to as China’s Louis XIV. His long reign lasted from 1661 to 1722. At the beginning of the novel, the Manchus have been ruling China for a little over twenty years, and are gradually, and ruthlessly, managing to extinguish the last residual sparks of the Chinese Resistance, in the South and the Southwest. The prologue, which was written during the height of the early excesses of the disastrous Cultural Revolution in Mainland China, echoes some of the political cut and thrust of that so-called revolution, in reality a bloody holocaust, details of which would have been fresh in the minds of Cha’s readers.

The prologue describes in gruesome detail the persecution of Loyalist intellectuals during the 1660s. Readers impatient for a taste of the kungfu low life that permeates most of the book have to wait until the first chapter.

On the Dragon Throne at the opening of the novel is the young Emperor Kangxi, one of the grandest monarchs in the whole of Chinese history. Principal among the underground organisations fighting Manchu rule is the newly formed Triad Secret Society, and in the pages of The Deer and the Cauldron we encounter many a colourful Triad member, including — as I call them in my translation — Big Beaver, Scarface Jia, Goatee Wu, Baldy Wang and Squinty Cui. The novel weaves its way through a host of historical events, painting a broad picture of the Chinese political landscape, culminating, at the end of the third volume, in the Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed between China and Russia in the year 1689.

Holding all these episodes together is a wonderful character of Louis Cha’s invention, Trinket 韋小寶, surely one of the most unforgettable characters in Chinese fiction, an incorrigible scamp, the opportunistic, lazy, amoral, sadistic but ultimately likeable and unforgettable, son of a coarse singsong-girl called Spring Fragrance from the prosperous southern city of Yangzhou. Trinket is an unlikely, reluctant, and highly unconventional, kungfu practitioner, a fake pilgrim who, together with his comrade-in-arms Whiskers Mao, pits his raw skills against some of the greatest living fighters of his day, including some redoubtable Manchu warriors, relying on trickery rather than valour or methodical training. At the heart of the plot is this scamp’s extraordinary friendship with the young Emperor. As Louis Cha himself has written: ‘Frankly, when I started writing Deer, during the first few months, I had no clear notion of what sort of character Trinket was going to be, he just grew on me slowly, bit by bit… He has many of the common Chinese qualities and failings, but he is certainly not meant to be a “type” of the Chinese people.’

Trinket somehow manages to have a finger in every available pie, and along the way assembles a veritable harem of beautiful women. Finally after a lifetime of relentless palace intrigue and endless kungfu adventures, having survived many a dangerous encounter with the palace impostor masquerading as the Dowager Empress — Trinket simply calls her the Old Whore — and having come up against the sinister and fanatical underground sect, the Mystic Dragons, based on Snake Island, with their powerful mantra-based kungfu, after a series of colourful love-affairs, one with the beautiful Chen Yuanyuan, known as the Peerless Consort, another with the glamorous Russian Princess Sophia, Trinket finally decides that he’s had enough; it’s time to quit, and he returns with his many wives to Yangzhou, his old home in the south: ‘opting for a life of simple pleasure, his ultimate destiny shrouded in mystery.’ He builds out of his multiple identities an absorbing and extraordinary card-castle of a life. It is his mercurial personality above all that turns the book into what the distinguished Hong Kong critic Stephen Soong 宋琪 has called: ‘a roller-coaster of a novel, packed with thrills, with fun, rage, humour, and abuse, written in a style that flows and flashes like quicksilver.’ An anonymous reader remarks on one of the countless Cha websites, that Trinket is the kind of friend who would have had not the slightest qualm about helping himself to your money and then your wife. Translating and indeed adapting and interpreting The Deer and the Cauldron for a foreign audience is to a very large extent about how to represent this obnoxious brat in English.

Cha himself, at the official launch of the first volume of the translation in Hong Kong, pointedly disowned Trinket. On this point I ventured to disagree with him. He also took exception to the way we abridged his work, from five volumes to three. This abridgement had in fact been deemed necessary by my silent collaborator in the project, my father-in-law David Hawkes. He translated half of the chapters, but did not wish his name to be put on the books. The French Sinologist and translator Jacques Pimpaneau had proposed the same approach to Cha many years earlier, when discussing a possible French version.

Louis Cha’s novels have been a runaway success in the Chinese reading world, generating a powerful mystique, a cult following, and countless by-products. As Sheryl WuDunn wrote in the New York Times, he is: ‘virtually a one-man literary movement, his thirty-six volumes of chivalry and romance mesmerizing both Chinese peasants and foreign academics alike.’

Now that the globe is becoming progressively more and more fascinated by the phenomenon of China, it is high time for this hilarious tale, this rattling yarn, to be made accessible to the English-speaking world, offering them a taste of true Chinese popular culture.

— John Minford

***

Postscript

In June 1993, East Asian History, the academic journal that I edited from 1989 to 2007, published two richly illustrated chapters from The Deer and the Cauldron, along with a lengthy introduction by the translator. We also produced the material as a stand-alone volume funded by Louis Cha. Interested readers are encouraged to consult that issue of East Asian History here.

— The Editor