廬山真面目

It is five years since we published ‘A Monkey King’s Journey to the East’, the inaugural article in China Heritage, and ten years since what would soon become the irresistible rise of Xi Jinping. We mark this occasion by launching a series of interconnected essays under the title Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

In ‘The True Face of Mount Lu’, the preface to our China Heritage series on the inaugural decade of the Xi Jinping era, we ascend Mount Lu, or Lu Shan, the Hermitage Mountain, in Jiangxi 江西省廬山. One of China’s most famous mountains, and a modern national park, Mount Lu has inspired poets, scholars, recluses, religious devotees over the ages. In the twentieth century the hill station at Guling provided both escape from the summer heat as well as a political platform for leaders both of the Nationalists and the Communists. During the era of High Socialism in the People’s Republic of China (c. 1949-1978) Mount Lu was the stage for the rise and the fall of the the most extreme policies of Mao Zedong and his co-conspirators, as well as for Mao’s cult of personality.

The complex terrain and numerous peaks of Mount Lu provide many perspectives both on the mountains themselves and the landscape surrounding it. Mount Lu frustrates the ambitious who hope to gain an all-encompassing perspective; these heights provide no olympian vantage point from which to survey or dominate the world. Rather, Mount Lu offers beguiling viewpoints and multiple angles from which to contemplate the passing cavalcade of history. It is for this reason that we offer the following meditation on Mount Lu as the prologue to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.

***

We are grateful to Lois Conner for allowing us to use some of work she made during our travels on and around Mount Lu in July 2004 as part of our long-term collaboration on Chinese landscapes. We are also grateful to Callum Smith, the designer of China Heritage, for creating our new masthead with Lois’s photograph of the Temple of Confluence and the peaks of the Five Old Ones.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

1 January 2022

***

Further Reading:

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium — China Heritage Annual 2022, 1 January 2022-

- China Heritage Annual 2021: Spectres & Souls

- ‘Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’, China Heritage, 13 July 2021

- ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, SupChina, 24 August 2021

- ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Namewee 黃明志 et al, ‘The Right to Know & the Need to Lampoon’, China Heritage, 18 October 2021

- W.H. Auden & Su Shi 蘇軾, ‘Streams Descending Turn to Trees that Climb’ — five years of China Heritage, 16 December 2021

- New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記, 1 January 2017, continuing

- Bathing Baby Buddha, China Heritage, 3 May 2017

- Ninth of the Ninth 重陽 Double Brightness, China Heritage, 28 October 2017

- Frederick C. Teiwes and Warren Sun, The Tragedy of Lin Biao: Riding the Tiger During the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1971, London: Hurst, 1996

- Susan E. Nelson, ‘Catching Sight of South Mountain: Tao Yuanming, Mount Lu, and the Iconographies of Escape’, Archives of Asian Art, vol. 52 (2000/2001): 11-43

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Beijing, a garden of violence’, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 9:4 (2008): 612- 639

- Zhang Longxi, ‘The True Face of Mount Lu: On the Significance of Perspectives and Paradigms’, History and Theory, vol.49, no.1 (February 2010): 58-70

***

橫看成嶺側成峰,遠近高低各不同。

不識廬山真面目,只緣身在此山中。

— 蘇軾

Seen straight on, a range; from the side, a peak—

Far, near, high, low, it is never the same.You cannot know the true face of Mount Lu

Because you are in the mountain’s midst.

— Su Shi, trans. Susan E. Nelson

Su Shi (蘇軾, 1037-1101) travelled to Mount Lu 廬山, also known as Hermitage Mountain 匡廬, in the spring of 1084 CE; he was on the way to take up a new official position. In his ‘Account of a Visit to Mount Lu’ 自記遊廬山 he says ‘initially I had no plan to write any poems’ 發意不欲作詩 about the majestic landscape of the mountain, but his travels there were greeted with such delight by the monks and laypeople that he encountered in what was also a famous pilgrimage site that he soon found himself recording the delights to the visit in verse:

芒鞵青竹杖,自掛百錢遊。

可怪深山裏,人人識故侯。

Straw sandals, cane of green bamboo,

I roam, leaving strings of a hundred cash.

But I marvel how deep in the mountains

everyone knows the old count.*

— trans. Stephen Owen

*’The old count’ 故侯, a reference to Zhao Ping, Marquis of the Eastern Tumulus 東陵侯召平, who ended an illustrious official career tending a garden after the fall of the Qin dynasty. This self-deprecating reference indicates that, like the count, the poet has fallen from the height of grand office.

***

***

Wandering around the mountain range for ten days Su declared that Mount Lu was ‘the most splendid scenery, finer than one can adequately describe’ 往來山南地十餘日, 以為勝絕不可勝談. When visiting the Temple of the Western Grove 西林寺 located on the south-west saddle of the mountains, he composed a poem about the variegated vistas of the mountains and how the ‘true face of Mount Lu’ can never truly be grasped.

‘You cannot know the true face of Mount Lu/ Because you are in the mountain’s midst.’ 不識廬山真面目, 只緣身在此山中 is arguably Su Shi’s most famous line, one that is well-known and widely quoted in the Chinese world to this day. It is often cited when referring to the ever-changing nature of things, a confusing maelstrom, the unknowability of unfolding events, as well as the obscure motives of individuals or, for that matter, someone’s true colours. (A similar, although hardly poetic, line that expresses a similar state of befuddlement is: 當局者迷 dāng jú zhě mí, ‘those in the thick of it [find themselves] are confounded’.)

As Susan E. Nelson observes of an earlier period of political repression and internal exile:

‘The uneasy political climate of the late Northern Song brought a new influx of visitors and sojourners to the Lu range, among them some of the leading figures in the fierce ideological controversies of the period. It was a harrowing time for these people, as rival factions alternated in positions of power. Some of those in disfavor were banished for years to remote regions, others withdrew into obscurity.

‘The experience of exile, voluntary or compelled, tinged the intellectual history of the period in many ways. Among other things, it stimulated a new attention to historical figures known for their lot of exile or withdrawal during politically troubled times, and to Mount Lu, which had come to epitomize retreat culture. Su Shi (1037-1101) stopped there on his return from exile in 1084; like so many earlier visitors (and prompted, no doubt, by their accounts), he was deeply impressed by the numinous aura of the place.

The conversations he had at the Donglin Temple with the Chan monk Changcong touched on perceptions of the Buddha’s form manifest in the mountain, echoing the landscape epiphanies of the Donglin Buddhism of Huiyuan’s day. These revelations of the universal and sacred nature of Mount Lu—its Buddha—like nature are a subtext of the poem he inscribed on the wall of the Xilin-si (Western Grove Temple), a companion institution to the Donglin.’

— Susan E. Nelson, ‘Catching Sight of South Mountain’

Archives of Asian Art, vol. 52 (2000/2001): 21

* For another poem by Su Shi on the topic of Mount Lu, see ‘Streams Descending Turn to Trees that Climb’ — five years of China Heritage

***

***

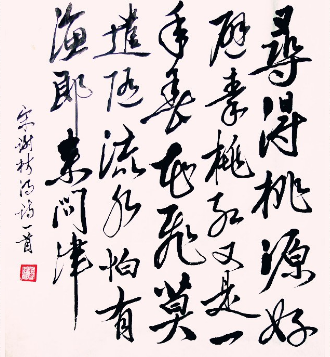

Copies of Su Shi’s poem are featured at the refurbished old Temple of the Western Grove and festoon tourist gewgaws but, for a time the words ‘the true face’ 真面目, that is the essential nature of life, the spirit, a place, person or event, were to be found on the lintel of a decrepit temple dormitory at the Temple of the Confluence 海會寺, located on the north-east side of Mount Lu. The thousand-year-old monastery was located at the foot of the Peaks of the Five Old Ones 五老峰, one of the most famous ridges of the Mount Lu range where the waters of the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake 鄱陽湖 meet.

The name Confluence Temple was a reference both to the geography of its setting and to the fact that over the centuries talented monks, mendicants and laypeople often gathered there during their pilgrimage to the mountain. It was destroyed during the Taiping War in the mid-nineteenth century and rebuilt in the waning years of the Qing dynasty. By the time we visited in the summer of 2004, the main temple was a ruin and ‘True Face’ hall faced a dried out pond for lotuses constructed in the shape of a crescent moon. Once upon a time, a copy of the Lotus Sutra in the hand of the illustrious calligrapher Zhao Mengfu 趙孟黻 was said to have been kept in the temple, which was being painstakingly rebuilt by a retired cadre who had taken the tonsure and was known by her religious name, Yanyin 釋衍音, and a number of acolytes. She had originally spent time at the famous West Forest Temple, where Su Shi had written his poem nearly a millennium earlier, but she found the atmosphere of what was once more a wealthy and busy religious site to be unconducive to her religious pursuits.

In 2016, media sources reported that the local authorities had rezoned the area and demolished what remained of the Temple of Confluence. Yanyin, the devoted caretaker of the temple, and her followers were becalmed.

***

***

蘇軾《自記遊廬山》

僕初入廬山,山谷奇秀,平生所未見,殆應接不暇,遂發意不欲作詩。已而見山中僧俗,皆云:蘇子瞻來矣。不覺作一絕云:芒鞵青竹杖,自掛百錢遊。可怪深山裏,人人識故侯。既自哂前言之謬,又復作兩絕云:青山若無素,偃蹇不相親。要識廬山面,他年是故人。又云:自昔憶清賞,初遊杳靄間。如今不是夢,真箇是廬山。是日有以陳令舉《廬山記》見寄者,且行且讀,見其中雲徐凝、李白之詩,不覺失笑。旋入開先寺,主僧求詩,因作一絕云:帝遣銀河一派垂,古來惟有謫仙辭。飛流濺沫知多少,不與徐凝洗惡詩。往來山南地十餘日,以為勝絕不可勝談,擇其尤者,莫如漱玉亭、三峽橋,故作此二詩。最後與摠老同遊西林,又作一絕云:

橫看成嶺側成峰,到處看山了不同。

不識廬山真面目,只緣身在此山中。僕廬山詩盡於此矣。

***

Fleeing The Qin 避秦

Centuries before Su Shi visited Mount Lu, the famous recluse Tao Yuanming, having abandoned the burdens of official life had sought refuge there. Some argue that the numinous landscape inspired ‘Peach Blossom Source’, Tao’s famous essay about escaping tyranny to find peace in rural utopia.

The recluse-poet Tao Yuanming (陶淵明, 365?–427 CE) has long been celebrated for his association with the chrysanthemum, which he is said to have cultivated in his garden at Mount Lu. Famed for having given up service to the state for a life of leisure, writing, drinking and self-sufficient farming at Mount Lu (or South Mountain 南山, as he refers to it), Tao Yuanming is the archetype of a man who has rejected the onerous demands of the day to pursue instead the simple pleasures of contemplation, drinking, freedom, the countryside and writing. His quest for quietude, one that is also tinged with all-too-human worldly concerns and fears, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists and writers alike. Over the centuries, his freewheeling lifestyle has also been a subject for artists and other poets. Throughout the revolutionary twentieth century, sanctimonious progressives and finger-wagging wowsers alike decried his escapism as a dangerous example for the young.

***

***

Scholars have made the case that the otherworldly landscape of Mount Lu inspired Tao Yuanming’s most famous essays, ‘Record of the Peach Blossom Spring’ 桃花源記 which tells of a place untrammeled by the cruel uncertainties of the outside world. The narrator, an accidental visitor to the hidden rural idyll, learns that the people there had long ago ‘Fled The Qin and the Disorders of the Time’ 避秦時亂:

…There was a small opening in the mountain, and it seemed as though light was coming through it. The fisherman left his boat and entered the cave, which at first was extremely narrow, barely admitting his body; after a few dozen steps it suddenly opened out onto a broad and level plain where well-built houses were surrounded by rich fields and pretty ponds. Mulberry, bamboos and other trees and plants grew there, and criss-cross paths skirted the fields. The sounds of cocks crowing and dogs barking could be heard from one courtyard to the next. Men and women were coming and going about their work in the fields. The clothes they wore were like those of ordinary people. Old men and boys were carefree and happy.

… 林盡水源,便得一山,山有小口,彷彿若有光。便捨船,從口入。初極狹,才通人。復行數十步,豁然開朗。土地平曠,屋舍儼然,有良田美池桑竹之屬。阡陌交通,雞犬相聞。其中往來種作,男女衣著,悉如外人。黃發垂髫,並怡然自樂。

When they caught sight of the fisherman, they asked in surprise how he had got there. The fisherman told the whole story, and was invited to go to their house, where he was served wine while they killed a chicken for a feast, When the other villagers heard about the fisherman’s arrival they all came to pay him a visit. They told him that their ancestors had fled the disorders of Qin times and, having taken refuge here with wives and children and neighbors, had never ventured out again; they had lost all contact with the outside world. They asked what the present ruling dynasty was, for they had never heard of the Han, let alone the Wei and the Jin. They sighed unhappily as the fisherman enumerated the dynasties one by one and recounted the vicissitudes of each. The visitors all asked him to come to their houses in turn, and at every house he had wine and food. He stayed several days. As he was about to go away, the people said,

‘There’s no need to mention our existence to outsiders.’

見漁人,乃大驚,問所從來。具答之。便要還家,設酒殺雞作食。村中聞有此人,咸來問訊。自云先世避秦時亂,率妻子邑人來此絕境,不復出焉,遂與外人間隔。問今是何世,乃不知有漢,無論魏晉。此人一一為具言所聞,皆嘆惋。余人各復延至其家,皆出酒食。停數日,辭去。此中人語雲:不足為外人道也。

— translated by J.R. Hightower, in Minford and Lau, eds,

Classical Chinese Literature, vol. I, 2000, pp.515-516

In this depiction of an idyllic world of peace and contentment, Tao Yuanming says that the inhabitants of the Peach Blossom Spring sought the place out in order ‘to flee The Qin’, that is, they found a refuge from the harsh rule of the Qin dynasty and its infamous First Emperor 秦始皇.

Olympian Hubris on Mount Lu

As we have noted many times in China Heritage, Mao Zedong had a penchant for comparing himself favourably to China’s primordial autocrat (in our own day, the First Emperor also features in all-embracing worldview of Xi Jinping).

As chaos enveloped China at the height of the Great Leap Forward in 1959, Mao and his Communist colleagues convened at Mount Lu. The comfortable old summer villas of the town of Guling 牯嶺 (a Chinese transcription of ‘Cooling’, the name used by the foreigners who used the area as a hill station from the late-nineteenth century) now housed senior cadres and the meeting rooms and large auditorium built by Chiang Kai-shek, who had refitted the resort as his summer capital 夏都, became the site of one of modern China’s most momentous, and tragic, political clashes, known as the Lushan Conference 廬山會議.)

The clash between Party leaders at Mount Lu in the summer of 1959 is regarded by many party historians and specialists as the first time that conflict within the ruling elite spilled into the open (that is, within the Communist Party, the details remained a carefully guarded secret from the vast majority of Chinese). As Mao Zedong, in a mood of irrational hubris and paranoia, haughtily overruled some of his closest associates, he also disrupted the style of collective leadership that had governed the Communist Party for over twenty years. It was an overt swerve towards one-man rule and, not long after, it would be bolstered by a dangerous cult of personality.

Despite the drama at the Lushan Conference, or perhaps because of it, Mao composed a number of famous poems in the classical style. ‘Ascent of Lushan’ 七律·登廬山, is dated 1 July 1959:

Perching as after flight, the mountain towers over the Yangtze;

I have overleapt four hundred twists to its green crest.

Cold-eyed I survey the world beyond the seas;

A hot wind spatters raindrops on the sky-brooded waters.

Clouds cluster over the nine streams, the yellow crane floating,

And billows roll on to the eastern coast, white foam flying.

Who knows whither Prefect Tao Yuan-ming is gone

Now that he can till fields in the Land of Peach Blossoms?

— trans. in Mao, Poems, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1976, p.37

The unbridled Communist leader mocks Tao Yuanming (before retiring from the world, Tao was employed as a local prefect for some eighty days) and his fanciful Peach Blossom Spring; after all, China under his direction was now in the process of creating an ideal agricultural realm the like of which Tao and his ilk over the centuries had only ever dreamt. He chides the ancient recluse for being unwilling to engage in meaningful productive labour:

陶令不知何處去,桃花源里可耕田?

Who knows whither Prefect Tao Yuanming is gone

Now that he can till fields in the Land of Peach Blossoms?

***

***

Eleven years later, in the summer of 1970, Mao and the Party’s central committee that had been radically transformed by the purges of the Cultural Revolution convened again at Mount Lu. One faction of Mao’s supporters now declared the Chairman to be an unique ‘genius’, backing up the claims with a digest of quotations from Marx and Lenin (here one thinks of Wang Hui 汪暉, the Beijing academic cum-intellectual courtier, and his celebration of Lenin’s ‘revolutionary personality’, with its not-so-subtle allusions to the genius of Xi Jinping). Realising that Mao was preparing to rid himself of this unctuous group, one headed by none other than Marshal Lin Biao, the main beneficiary of the purge at the 1959 Lushan Conference and the chief architect of the Mao cult, other adroit Maoist boosters decried this new ‘cult of genius’ by claiming that its proponents were ‘taking advantage of Chairman Mao’s modesty in a devious attempt to downgrade Mao Zedong Thought’ 利用毛主席的謙虛,妄圖貶低毛澤東思想.

Mao accused Chen Boda (陳伯達, 1904-1989), a close associate and long-time political secretary who was the spokesman for the ‘genius theory’ of betrayal. With characteristic acerbity Mao relegated his old amanuensis to oblivion with the words:

‘[In proposing the “genius theory” Chen] has launched a surprise attack. He’s even lit some brush fires and attempted to fan the flames. He’s applied himself with such energy that it looks like he wants to throw all under heaven into chaos; maybe he thinks he can bomb Mount Lu and reduce it to rubble. Or, perhaps he believes that he can stop the earth from rotating on its axis.’

採取突然襲擊,煽風點火,唯恐天下不亂,大有炸平廬山,停止地球轉動之勢。

— 毛澤東, ‘我的一點意見’, 1970年8月31日

Mao ousted Chen Boda and launched a major rectification campaign of the Party, a housecleaning that so affrighted Lin Biao, his avowed close-comrade-in-arms who in April 1969 had been named as the chairman’s successor, that in September 1971 the marshal made an unsuccessful attempt to flee China, dying with his wife and son in a mysterious plane crash. With the end of Chen, Lin and a host of their allies, arrested for the most part on trumped up charges, Mao also reined in his personality cult and made moves to repair the destruction of the previous five years. One of those moves was to recall Deng Xiaoping, a man for his administrative acumen, from exile. This would mark not only the end of the excesses of one-man rule, it also resulted in the furtive beginnings of the reforms that eventually transformed the Chinese economy, even if they did little to change the root causes and abiding problems of one-party rule.

***

Shroud Your True Face

‘You cannot know the true face of Mount Lu/ Because you are in the mountain’s midst’ is a poetic line that has always resonated with Buddhist ‘world-wariness’; it accords with the understanding of practitioners of various forms of meditation, referring as it does to the quest to move beyond self and other, subject and object. Only at such a spiritual distance is it possible for the heart-mind to achieve a measure of clarity, if not true insight. The ‘original face’ beclouded by the welter of events and the cascade of the trivial may then be perceived and, when its features grasped even offer moments of enlightenment.

In January 2022, as China, including the fallen territory of Hong Kong, Taiwan and the fractious communities of the world face the end of a decade of Xi Jinping’s rule as the Chairman of Everything — and confront the possibility of the continuation of his tenebrous tenure as the head of the party-state-army of the Chinese People’s Republic — it is salutary to recall those long-past events on Mount Lu; the hubris of Mao, the sycophancy of his courtiers; and, the plots of his comrades. They bracketed the rise and fall of Mao Zedong’s cult of personality, as well as an era of one-man rule that steered China into disaster.

Mount Lu’s ‘true face’ is endlessly beguiling and multifarious; the dark features of autocracy, however, are plain for all to see.

A Wunderkammer of Masks

‘In China, anyone who wants to offer a different point of view, as well as anyone who actually expresses a different opinion, invariably ends up discredited and undone, their lives forfeit, their families ruined. People who truly want to be free know that in a nation mired in slavish compliance the precondition of freedom is the right to disagree. But by expressing a discordant view you are, in effect, declaring war on all of the complicit scum; defeat awaits. If you want to survive you have to shroud your true face 真面目.

‘Throughout history China has proven time and again that its people have a boundless range of masks from which to choose. Even foreigners are awed by this bounty.’

— Liu Yazhou, ‘Re-commemorating the Jiashen Year of 1644’ (2004)

在中國,每一個想要提不同意見和敢於提不同意見的人,最後都是身敗名裂,家破人 亡。提不同意見,是在舉國皆奴中成為自由人的最起碼的先決條件。提不同意見,就是對狗才宣戰,但往往失敗。要想生存,就是要把自己的真面目包起來。古今中外,只有中國的臉譜多,令外國人嘆為觀止。

***