Jottings in New Sinology

On 22 December 1972, the government of New Zealand cut off its decades-long diplomatic relationship with the Republic of China, which had been based on the island of Taiwan since 1949, and recognised the People’s Republic of China with its capital in Beijing and ruled over by the Chinese Communist Party. This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of that consequential decision.

Encountering China: New Zealanders and the People’s Republic, edited by Duncan Campbell and Brian Moloughney and published by Massey University Press in December 2022, was produced to commemorate the new phase in New Zealand-China relations.

The following essay by Duncan Campbell, one of the founding members of China Heritage, is a chapter in Encountering China. We preface it with some observations by Chris Elder, a former New Zealand ambassador to Beijing, and the publisher’s questionnaire related to the volume. We have appended the Chinese text of ‘The Earl of Zheng Overcame Duan in Yan’ 鄭伯克段於鄢 to Duncan’s essay, along with a translation by James Legge (1815-1897).

[Note: for more on James Legge, see The Wairarapa Talks:

- Lecture Two: James Legge (1815-1897) and the Chinese Classics, Video

- Lecture Two: James Legge, Handout]

***

Duncan Campbell and I first encountered each other when I was visiting Beijing from Shenyang, where I was studying at Liaoning University. Mao was recently dead and I was contemplating giving up on the inhospitable environment ‘outside the pass’ 關外. In early 1977, the Ministry of Education announced that Nanking University, a college in the former capital of the Republic of China, would be accepting foreign students. I hankered to move south but the authorities at Liaoning University who told me that I was regarded as being an obstreperous ‘bourgeois anarchist’ forbade it. (My father beat the Communists to if: years earlier, he expressed a similar evaluation of my character.) I would, however, be permitted to continue my studies in Shenyang until the summer of 1978. Instead, I decided to move to Hong Kong in the summer of 1977 to work with Lee Yee (李怡 1936-2022), editor of The Seventies Monthly. On a trip back to the People’s Republic during the autumn of 1977, I encountered Duncan again, this time he was happily ensconced with many other friends at Nanking University. I’ve been wistful about the forbidden opportunity to study with them ever since.

***

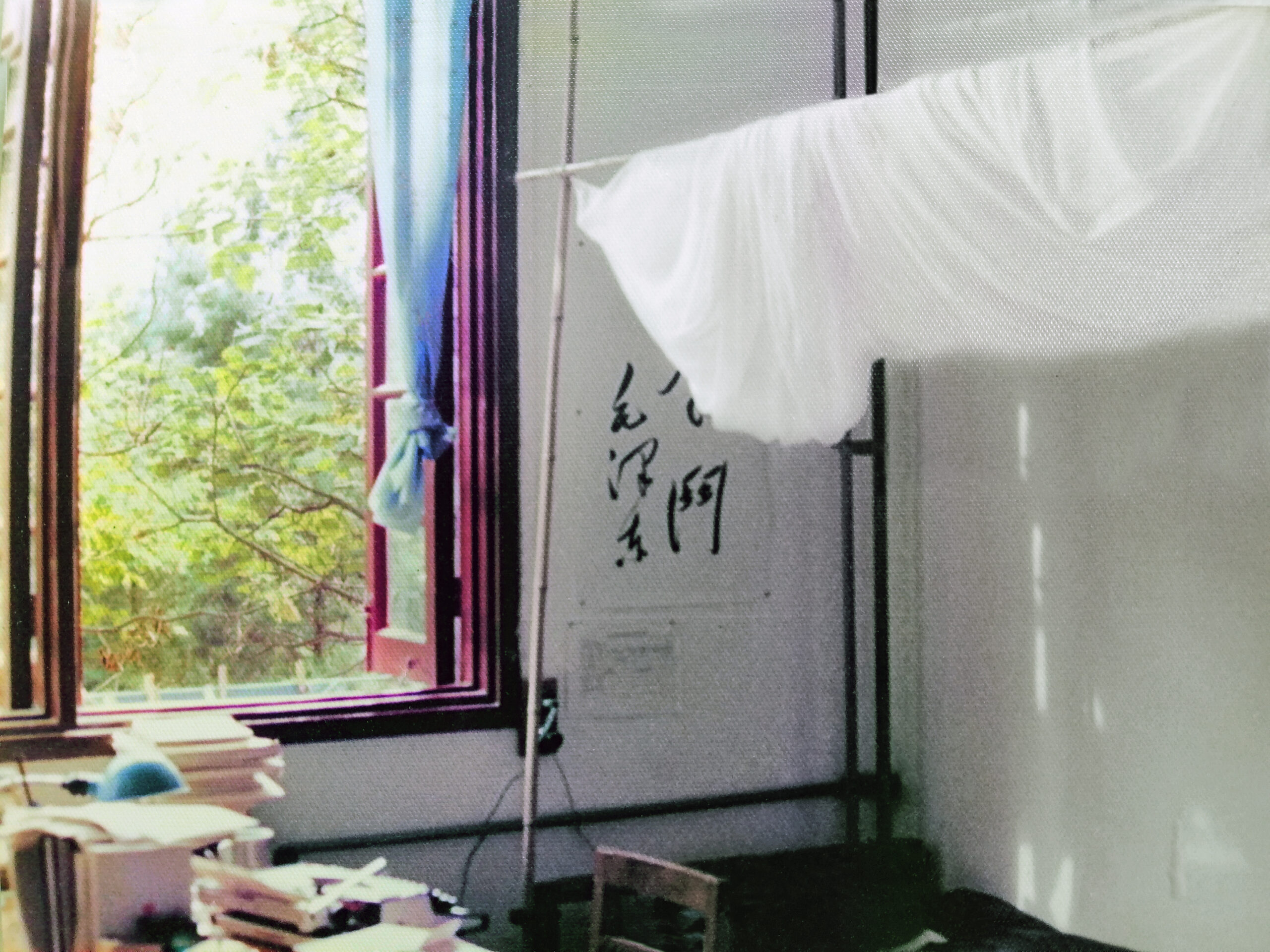

We are grateful to the editors and publisher of Encountering China for permission to reprint the following material, and to Lois Conner for kindly restoring the old photograph of Duncan Campbell’s dormitory at Nanking University. ‘The Earl of Zheng Overcame Duan in Yan: China’s Past in Our Futures’ is produced as part of the series Jottings in New Sinology 後漢學劄記.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, Asia Society

6 December 2022

***

Selected Essays and Translations by Duncan Campbell:

- Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 17, March 2009

- Wei Li 韋力, Lingering Traces: In Search of China’s Old Libraries, introduced and translated by Duncan Campbell, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 18, June 2009

- The Heritage of Books, Collecting and Libraries, Special Issue of China Heritage Quarterly, Guest editor: Duncan M. Campbell, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 20, December 2009

- The Universal Library, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 20, December 2009

- Huang Shang 黃裳, On Reading Tung Chuin’s A Record of the Gardens of Jiangnan, translated by Duncan Campbell, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 20, December 2009

- Paradise Regained?, A Review of Vera Schwarcz, Place and Memory in the Singing Crane Garden, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 21, March 2010

- Zhang Dai 張岱, The Ten Scenes of West Lake 《西湖十景》, translated by Duncan Campbell with photographs by Lois Conner, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 28, December 2011

- China Heritage Glossary: 景 Jǐng, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 28, December 2011

- Zhang Dai 張岱, Searching for the Ming, translated by Duncan Campbell, China Heritage Quarterly,No. 28, December 2011

- Zhang Dai 張岱, Old Man Min’s Tea 閔老子茶, translated by Duncan Campbell, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 29, March 2012

- Letters by Yuan Hongdao 袁宏道, Selected from his Deliverance Collection 解脫集, translated by Duncan M. Campbell, with Helen Gruber, Han Lu, Jiang Qian, Andrew Ritchie and Yang Bin, China Heritage Quarterly, Nos. 30/31, June/September 2012

- China Heritage Glossary: On Idleness 閒, China Heritage, 1 February 2017

- From One to Ten and Back Again — 10 October 2022, Appendix XVIII 雙十 of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, China Heritage, 10 October 2022

An Introductory Note

Chris Elder

There is an odd symmetry about the beginning and the end of the 50-year period. Its beginnings came at the end of a time during which New Zealand kept China at arm’s length, essentially because of the United States’ unwillingness to treat with it. It ends at a time when the United States and China are once again at odds, and the stand-off between the two presents a difficult balancing act for small nations such as New Zealand.

China does not always present itself in a sympathetic light. It is perceived to be heavy- handed in the way it deals with national minorities, in its administration of the ‘one-country, two-systems’ approach to Hong Kong, even in apparent attempts to influence the behaviour of Chinese people resident outside China. At the same time, it has demonstrated a growing and at times unwarranted assertiveness in its dealings with other countries. It is a measure of the degree to which such behaviour gives rise to dismay that some potential contributors to this volume have opted not to do so, either because of their profound disagreement with aspects of Chinese policy, or because of fear of repercussions for themselves or others should they speak freely.

— from the introduction to Encountering China

***

Encountering China

New Zealanders and the People’s Republic

edited by Duncan Campbell & Brian Moloughney

The Publisher’s Questionnaire

Why did you want to create a book around the fiftieth anniversary of NZ and China diplomatic relations?

The decision taken in December 1972 to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (at the expense of the Republic of China), 20-odd years after its founding, has proven a consequential one. Over the course of 50 years, the engagement with China has been transformative of both our economic circumstances and the makeup of our society. The People’s Republic is now one of Aotearoa | New Zealand’s most important but most challenging of relationships. In light of such circumstances, we thought that the occasion called for some reflection on the part of individual New Zealanders about the various ways that China had impinged upon their lives, in the hope that this might serve to offer a more nuanced (and complex) view of both our countries, and the traffic between them.

How did you decide on who to approach?

A group of those involved with the People’s Republic over the years got together and started drafting up lists of people who might be approached. We then convened a workshop to foster interest in the project, and suggestions were made also about possible posthumous contributions. For various reasons, some of those we approached decided not to be involved. An early decision was made to limit the number of contributions to 50 voices and so, sadly, a number of the contributions offered us could not be included, by reason of either space or balance.

What was their brief?

The book is certainly not the “official” account of the relationship. Rather, we wished to capture insights into aspects of this relationship and its evolving meanings in the lives of individual New Zealanders, bringing together the voices of some 50 people who, through text (prose or poetry), image, or photograph, write about what this relationship has meant to them and the trajectory of their lives. The anthology was intended to be commemorative rather than, necessarily, celebratory, reflections fixed on the page before they were forgotten. What did the relationship mean then? What does it mean now? How is this relationship best thought of? How will it be thought of in the future? Moments, events, sights or smells, insistent memories of triumphs or less than complete successes, occasions that changed one’s understanding or appreciation of aspects of Chinese life and culture, or which didn’t, encounters with people or places that nag at the mind, fragments, vignettes, snapshots, snatches of conversations, real or imaginary, extracts from longer works, instances of insight or misunderstanding, cultural clashes, cultural commonalities.

Who is this intended reader? And what do you hope they gain from reading the book?

Firstly, we hope that anyone who has engaged with China over the course of the last half century of the relationship between New Zealand and the People’s Republic of China might care to dip into this anthology. We hope that it offers some individual reflections on the lived reality of an engagement with the country and her people that might be interesting, even useful, as we grope our way into the future. More generally, we hope that anyone interested in an evolving Aotearoa | New Zealand identity and the part that our relationship with China might have played in this process will be interested in the book, and moved by some of the tales it tells.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered during your selection and editing of the chapters?

The richness and the diversity of the responses to China on the part of ordinary New Zealanders. The deepness of the cultural connections.

Were there any challenges in managing so many authors, and from such different backgrounds?

In general terms, the mainstream engagement with the People’s Republic of China on the part of ordinary New Zealanders has moved through phases of enchantment (70s-80s), disenchantment (after the violent suppression of protests in June 1989), fitful and wary re-engagement (mid-90s onwards), “Let the Good Times Roll” (early 2000s), to, presently, grave disquiet (about, for instance, human rights in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and elsewhere in the People’s Republic). But chronology did not offer any easy architecture for the anthology; some periods were under-represented, others over-represented, and in many cases, the contributions ranged over different periods, reflecting on the differences between these periods. We settled on a structure that grouped the contributions loosely under five themes: Beginnings, People, Place, Occasion, and Transformations. Throughout the editing process, we were intent on trying to retain the diversity of voice.

When did you first become interested in China?

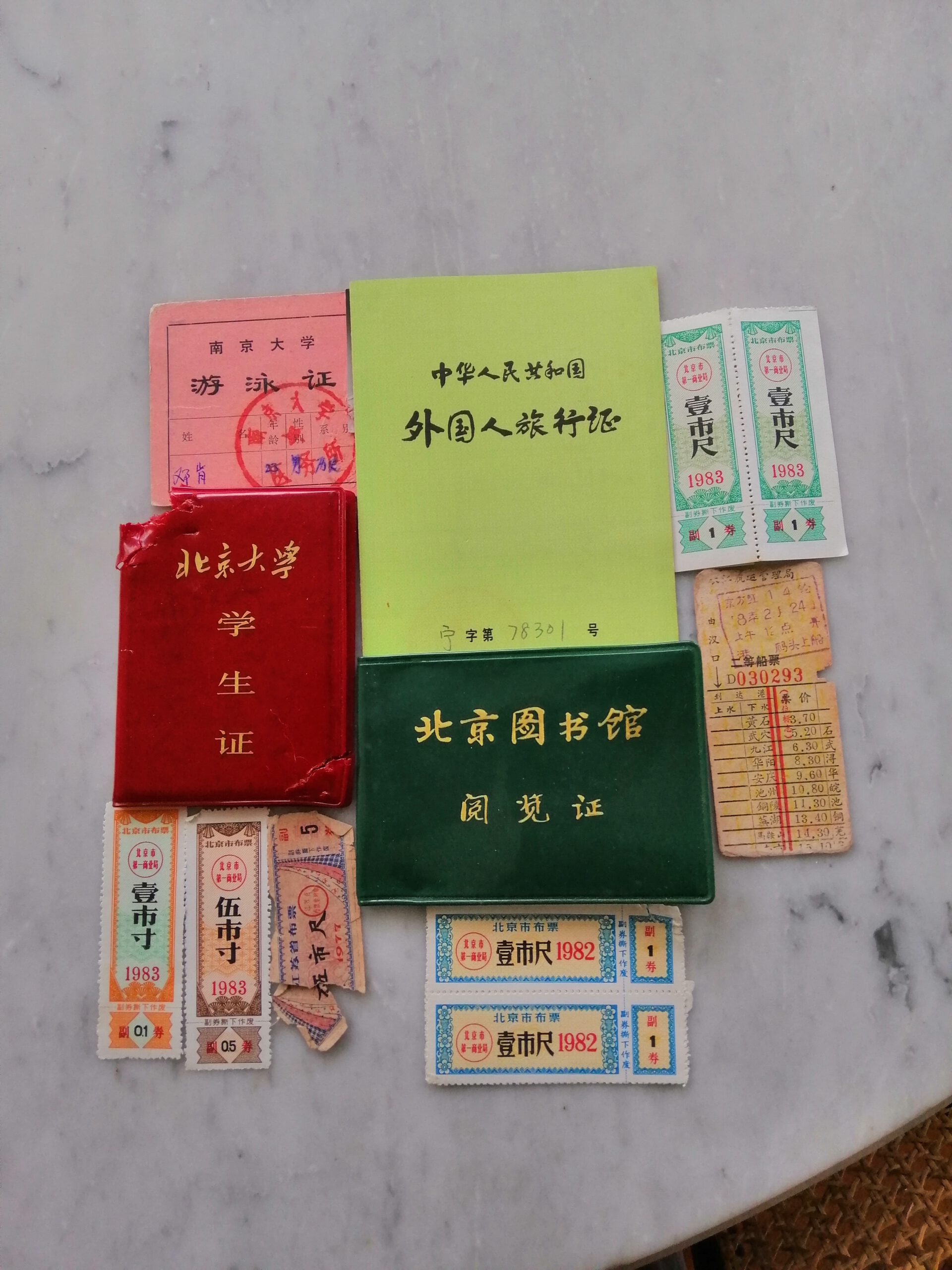

DMC: I started studying Chinese in Malaysia in the 1970s, having done a degree in English Literature and History at Te Herenga Waka | Victoria University of Wellington. When the opportunity to study in the People’s Republic of China under the auspices of the China Exchange Programme came by, I jumped at it, spending the years 1976-1978 there. I suppose that initially my motivations for doing so were largely political; that changed almost as soon as I walked across the Lo Wu Bridge over the Sham Chun River and into the People’s Republic. I’ve spent the rest of my life trying better to understand the experiences I had during those years, as China embarked upon its post-Mao Zedong transformation.

BM: In my case, I benefitted from good undergraduate teaching about Asia at the University of Canterbury, which followed a few years back-packing across the region, and together these experiences stimulated a desire to know more about China. This led to a period of study in China, supported by the China Exchange Programme, and then a PhD in Chinese history. The richness of China’s cultures and traditions, and the friends made along the way, have sustained my continued engagement with the place and its people.

What would be the most significant change in our relationship with China over the last 50 years?

The trading relationship. While the economic benefits of this have been of great value to New Zealanders, the anxiety now must be our over-dependence on the China market as destination for our products. And was our pre-Covid 19 over-reliance on both tourists and international students from the People’s Republic at all either desirable or sustainable, environmentally or ethically?

What is the greatest challenge for New Zealand today in our relationship with China?

For the first time in our history, we are now faced with the reality that our major trading partner works to values and practices that are, in many cases, antithetical to those that we try to hold fast to. And the geostrategic circumstances of the world have rapidly become more challenging, most obviously for us in the Pacific. How we seek to negotiate this treacherous landscape will be a challenge and will require of us increased levels of understanding of the realities of contemporary China.

If people could take one thing from this book what would you want it to be?

That China, however we might think about it, has played (and will continue to play) an often surprising part in our pasts, present, and futures. That China is a fundamental part of how we should think of ourselves, and our place in this world.

***

‘The Earl of Zheng Overcame Duan in Yan’

China’s Past in Our Futures

Duncan M. Campbell

Enrolling with the History Department of Nanking University in early September of 1977, after having studied Chinese language at the Peking Languages Institute for a year under the auspices of a New Zealand–China Student Exchange Scholarship, we were asked what we might like to study. Although my reasons for being in the People’s Republic of China, to the extent that I was fully conscious of them, were decidedly contemporary and largely political, I nonetheless suggested that it might be a good idea to learn some Classical Chinese or wényán 文言, the language that for thousands of years had underpinned the development of Chinese civilisation and its expansion of empire. It proved a fateful suggestion; almost 50 years later, I find myself still engaged in this task.

Several days after the question had been posed us, then, a small group of the some 15 foreign students allocated to the university that year turned to the first lesson in Volume One of (the only recently rehabilitated Peking University-based linguist) Wang Li’s (王力, 1900-1986) Classical Chinese 古代漢語, first published in 1962. The following year, when I acquired a copy of the first post-Cultural Revolution reprinting of the 1695 anthology of prose compiled by the Shaoxing school teacher Wu Chucai (吳楚材, 1655-1719) and his younger nephew Wu Diaohou 吳調侯, The Finest of Ancient Prose 古文觀止, I discovered that this traditional primer, too, commences its work with this text. The passage is a lengthy one, taken from the Zuo Commentary 左傳 to the Spring and Autumn Annals 春秋 traditionally attributed to Confucius.

It is dated to the first year of the reign of Duke Yin of the State of Lu (魯隱公, r. 721-711 BCE), the Duke ‘Sorrowfully swept away, unsuccessful’ 隱拂不成, as the great nineteenth-century Scottish translator James Legge (1815–1897) explains his posthumous name, and cued to a line in the annals that reads:

‘Summer, the fifth month; the Earl of Zheng overcame Duan in Yan.’

夏五月,鄭伯克段于鄢。

It tells the story of the two sons of the ruler of the powerful and wealthy vassal state of Zheng, Zhuang and Duan, and their mother’s partiality for the younger son at the expense of the elder one whose breech birth (wusheng 寤生) had alarmed her. When in time their father dies and the elder son inherits the title of Duke, the mother conspires with Duan to have him replace Zhuang. Warned by his advisors about what was about to happen, Zhuang however refuses to act against his mother, both because she is, after all, his mother, and because he believes that in any case unrighteousness inevitably reaps its own just result.

When finally he is forced to act, overcoming Duan in Yan, the area to which Duan had fled, Zhuang has his mother incarcerated, vowing that ‘We will not see each other before we reach the Yellow Springs’ 不及黃泉無相見也. Regretting his actions soon thereafter, the duke’s dilemma is resolved by a loyal border official called Ying Kaoshu, who suggests to him that he have a tunnel dug deep enough to reach the subterranean springs where he could arrange to meet up again with his mother. When the two eventually do so, they burst into song. And the passage ends with an appropriate couplet from another of the Confucian Canon, the Book of Odes 詩經, in praise of filial sons.

Problems of succession, the intricate balance in the relationship between power and knowledge (Ying Kaoshu reminds Zhuang of his filial obligations to his mother by refusing to eat the meat broth offered him by the duke, on the pretext that he intended to take it home for his own mother to eat), the play of modes of word magic (in the line from the classic that occasioned this commentary, for instance, the Duke is demoted to Earl for his failure to properly educate Duan, and Duan is not referred to as the younger brother because he did not behave in the manner required of a younger brother), the eternal clash between high-faluting normative values and altogether more sordid political realities — the passage seemed a fitting introduction both to the classical language and to the abiding characteristics of Chinese political culture, contemporary as much as ancient.

During the mid-1970s, such issues were playing out along the plane-tree-lined streets of Nanking, as they were also within the walls of the university. Sun Shuqi 孫述圻, for example, the man given the task of being our preceptor, had not been allowed into a classroom for almost 20 years.

Others among his colleagues had suffered more grievously at the hands of the Red Guards unleashed on them by the Great Helmsman, Chairman Mao. Kuang Yaming 匡亞明, a great scholar of Confucianism and one of the first major victims of the Cultural Revolution, restored to the vice-chancellorship of the university soon after we arrived, had had his kneecaps smashed. Many of the recently returned books proudly displayed in the home of Cai Shaoqing 蔡少卿 had been defaced with large but painstakingly inscribed crosses over the names of their authors. (These books I caught sight of when this wonderful historian of secret societies, ignoring explicit university instructions to the contrary, invited us to join his family for a meal. Many years later, he in turn visited us in Wellington.)

The enraptured glint in Sun’s eyes as he now recited a text, the dart of his small, delicate hands as he sought to illustrate some point to us, revealed his joy at once again being in front of a class and allowed to read the books of old. In doing so, he lent us, if only briefly, the fond illusion that China’s past, in all its enthralling complexity, was once again to be allowed to inform its present and future in a manner unfettered by arid Marxist frameworks. ‘Practice’, after all, was now to be ‘the sole criterion for testing truth’ 實是檢驗真理的唯一標準, the Nanking University philosopher Hu Fuming 胡福明 had argued in his influential article of that title, which was published in the pages of the Enlightenment Daily 光明日報 in May 1978.

Tragically, however, if the massacre of June Fourth, in 1989, revealed the iron-cast political limits of the Reform and Opening Up 改革開放 era, the beginnings of which I had been witness to, more recent decades have disclosed the extent to which China’s renewed and emotionally-charged engagement with its various pasts (historical, cultural, social and religious) has been highjacked by the Party-State. Once consigned to the dustbin of history as an obstacle to modernity and then stigmatised as the explicit target for violence, labelled the Four Olds 四舊 of old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits, China’s past is now increasingly deployed in bombastic and vainglorious claims to exceptionality.

The past has been reduced to a singular master narrative that valorises unity above all else, and which relies upon an ahistorical notion of ‘Chineseness’. The centrality of these notions to the legitimacy of the Party-State and its various territorial claims finds easy evidence. Xi Jinping’s 習近平 first public act upon assuming presidency of the People’s Republic of China in 2012 was to pay a visit to the ‘Road to Revival’ 復興之路 exhibition at the newly-opened National Museum of China, an occasion on which he first spoke about ‘The China Dream’ 中國夢.

More recently, in Xi’s speech marking the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, ‘history’ is mentioned more than 20 times, the second half of what he had to say on this occasion punctuated by the phrase: ‘Taking history as our mirror, and creating our future, we must …’ 以史為鑒開創未來必須⋯. And yet a central consideration about that past is that this idea of ‘Chineseness’ was established at the expense of the brutal eradication of a multiplicity of alternative political and cultural entities. This ideal of a unified China only remained both viable and desirable to the minds of the élite, if only fitfully realised, to the extent to which it required (and continues to require) increasing levels of autocracy, particularly as the extent of empire grew rapidly during the late-imperial period. Further, in terms of China’s abiding contributions to global civilisation, these have been predominantly the products of periods of disorder and disunity, the Warring States period, for instance, or the Six Dynasties era.

I was reminded of the tyranny of this sanitised straitjacket of a past acceptable to party authorities recently when I was compiling a glossary to accompany a set of short stories by a contemporary Chinese author that I had translated for a publisher in the People’s Republic. My draft was returned to me, with some degree of embarrassment on the part of the editor with whom I was dealing, marked with the annotations of the internal censor. I had, it seems, perpetrated three categories of error:

- I had mentioned unmentionable names;

- I had failed to employ the Party-State authorised formula (or 提法 tífǎ) to refer to particular historical events; and,

- I had made mistakes, it was claimed, with the dating of, for instance, both the Yuan and the Qing dynasties, both of which ‘alien’ dynasties have now been given extended reigns, the better to be understood as part of Chinese history, the founding of the latter dynasty no longer dated to 1644 and the fall of Peking to the Manchus, for instance, or 1636 when they name themselves the Qing, but rather to 1616 when they declared themselves to be the ‘Later Jin’ 後金 dynasty. According to Document Number Nine, any deviation from authorised interpretations of China’s history represents ‘historical nihilism’ 歷史虛無主義.

I remember once asking Teacher Sun Shuqi what it was that he read in bed each night before falling asleep. His reply was that presently he was working his way through Fan Ye’s (范曄, 398-445) History of the Later Han 後漢書, a work that is commonly regarded as the most difficult of the Standard Twenty-four Histories. He was later to publish An Intellectual History of the Six Dynasties 六朝思想史. Both the Six Dynasties and the Later Han periods were notoriously chaotic periods, the first creatively so, the latter having descended into bloody tanistry. I often wondered if, as a victim of the Cultural Revolution, his knowledge of these earlier and unsettled periods of China’s history lent him a sense of comfort or induced one of despair.

It is often suggested that what fuels contemporary Sinological disenchantment with the People’s Republic of China is the extent to which that nation has failed to become ‘more like us’. In my case, I think that the opposite is perhaps closer to the truth. Only a China more comfortable with the complications of its own unruly past might best contribute to our collective search for a sustainable future. For now, a fragile and thin-skinned superpower, seemingly incapable of any authentic dialogue with either its own past or its present and future responsibilities, domestically the People’s Republic of China seems to have become a society characterised by a catastrophic collapse in trust, whilst externally, increasingly it acts with the swagger of the playground bully.

Is China to be understood as the repository of a civilisation that might have important contributions still to make to the wellbeing of humankind? Or will it continue to be simply another authoritarian one-party nation-state? If the former, then one suspects that that alternative future might be found somewhere amongst the many alternative pasts that characterise the grand arc of its historical trajectory.

The Earl of Zheng Overcame Duan in Yan

Chinese Text with a translation by

James Legge

鄭伯克段於鄢

初,鄭武公娶於申,曰武姜,生莊公及共叔段。莊公寤生,驚姜氏,故名曰寤生,遂惡之。愛共叔段,欲立之。亟請於武公,公弗許。

及莊公即位,為之請制。公曰:制,巖邑也,虢叔死焉,佗邑唯命。請京,使居之,謂之京城大叔。祭仲曰:都城過百雉,國之害也。先王之制:大都不過參國之一,中五之一,小九之一。今京不度,非制也,君將不堪。公曰:姜氏欲之,焉闢害。對曰:姜氏何厭之有。不如早為之所,無使滋蔓,蔓難圖也。蔓草猶不可除,況君之寵弟乎。公曰:多行不義,必自斃,子姑待之。

Duke Wu of Zheng had married a daughter of the House of Shen, called Wu Jiang, who bore Duke Zhuang and his brother Duan of Gong. Duke Zhuang was born as she was waking from sleep [the meaning of the text here is uncertain], which frightened the lady so that she named him Wusheng (born in waking) and hated him, while she loved Duan, and wished him to be declared his father’s heir. Often did she ask this of duke Wu, but he refused it.

When duke Zhuang came to the earldom, she begged him to confer on Duan the city of Zhi. “It is too dangerous a place,” was the reply. “The Younger of Guo died there; but in regard to any other place, you may command me.” She then requested Jing and there Duan took up his residence, and came to be styled Taishu (the Great Younger) of Jing city. Zhong of Ji said to the Duke, “Any metropolitan city, whose wall is more than 3,000 cubits round, is dangerous to the State. According to the regulations of the former kings, such a city of the 1st order can have its wall only a third as long as that of the capital; one of the 2nd order, only a fifth as long; and one of the least order, only a ninth. Now Jing is not in accordance with these measures and regulations. As ruler, you will not be able to endure Duan in such a place.” The Duke replied, “It was our mother’s wish;—how could I avoid the danger?” “The lady Jiang,” returned the officer, “is not to be satisfied. You had better take the necessary precautions, and not allow the danger to grow so great that it will be difficult to deal with it. Even grass, when it has grown and spread all about, cannot be removed;—how much less the brother of yourself, and the favoured brother as well!” The Duke said, “By his many deeds of unrighteousness he will bring destruction on himself. Do you only wait a while.”

既而大叔命西鄙北鄙貳於己。公子呂曰:國不堪貳,君將若之何。欲與大叔,臣請事之;若弗與,則請除之。無生民心。公曰:無庸,將自及。大叔又收貳以為己邑,至於廩延。子封曰:可矣,厚將得眾。公曰:不義,不暱,厚將崩。

After this, Taishu ordered the places on the western and northern borders of the State to render to himself the same allegiance as they did to the earl. Then Gongzi Lü said to the Duke, “A State cannot sustain the burden of two services;—what will you do now? If you wish to give Jing to Taishu, allow me to serve him as a subject. If you do not mean to give it to him, allow me to put him out of the way, that the minds of the people be not perplexed.” “There is no need,” the Duke replied, “for such a step. His calamity will come of itself.”

Taishu went on to take as his own the places from which he had required their divided contributions, as far as Linyan. Zifeng [the designation of Gongzi Lü above] said, “Now is the time. With these enlarged resources, he will draw all the people to himself.” The Duke replied, “They will not cleave to him, so unrighteous as he is. Through his prosperity he will fail the more.”

大叔完聚,繕甲兵,具卒乘,將襲鄭。夫人將啓之。公聞其期,曰:可矣。命子封帥車二百乘以伐京。京叛大叔段,段入於鄢,公伐諸鄢。五月辛丑,大叔出奔共。

書曰:鄭伯克段於鄢。段不弟,故不言弟;如二君,故曰克;稱鄭伯,譏失教也;謂之鄭志。不言出奔,難之也。

Taishu wrought at his defences, gathered the people about him, put in order buff-coats and weapons, prepared footmen, and chariots, intending to surprise Jing, while his mother was to open to him from within. The Duke heard the time agreed on between them, and said, “Now we can act.” So he ordered Zifeng, with two hundred chariots, to attack Jing. Jing revolted from Taishu, who then entered Yan, which the Duke himself proceeded to attack; and in the 5th month, on the day Xinchou, Taishu fled from it to Gong.

In the words of the text,—“The earl of Zheng overcame Duan in Yan;” Duan is not called the Earl’s younger brother, because he did not show himself to be such. They were as two hostile princes, and therefore we have the word “overcame.” The Duke is styled the Earl of Zheng simply to condemn him for his failure to instruct his brother properly. Duan’s flight is not mentioned, in the text, because it was difficult to do so, having in mind Zheng’s wish that Duan might be killed.

遂寘姜氏於城潁,而誓之曰:不及黃泉,無相見也。既而悔之。潁考叔為潁谷封人,聞之,有獻於公,公賜之食,食舍肉。公問之,對曰:小人有母,皆嘗小人之食矣,未嘗君之羹,請以遺之。公曰:爾有母遺,繄我獨無。潁考叔曰:敢問何謂也。公語之故,且告之悔。對曰:君何患焉。若闕地及泉,隧而相見,其誰曰不然。公從之。公入而賦:大隧之中,其樂也融融。姜出而賦:大隧之外,其樂也洩洩。遂為母子如初。

君子曰:潁考叔,純孝也,愛其母,施及莊公。《詩》曰:孝子不匱,永錫爾類。其是之謂乎。

Immediately after these events, Duke Zhuang placed his mother Jiang in Shing-ying, and swore an oath, saying, “I will not see you again, till I have reached the Yellow Springs [i.e., till I am dead, and under the yellow earth].” But he repented of this. By and by, Ying Kaoshu, the border-warden of the vale of Ying, heard of it, and presented an offering to the Duke, who caused food to be placed before him. Kaoshu put a piece of meat on one side; and when the Duke asked the reason, he said, “I have a mother who always shares in what I eat. But she has not eaten of this meat which you, my ruler, have given, and I beg to be allowed to leave this piece for her.” The Duke said, “You have a mother to give it to. Alas! I alone have none.” Kaoshu asked what the Duke meant, who then told him all the circumstances, and how he repented of his oath. “Why should you be distressed about that?” said the officer. “If you dig into the earth to the Yellow Springs, and then make a subterranean passage, where you can meet each other, who can say that your oath is not fulfilled?” The Duke followed this suggestion; and as he entered the passage sang, “This great tunnel, within, With joy doth run. When his mother came out, she sang, “This great tunnel, without, The joy flies about.” [After this, they were mother and son as before.]

A superior man may say, “Ying Kaoshu was filial indeed. His love for his mother passed over to and affected Duke Zhuang. Was there not here an illustration of what is said in the Book of Poetry, “A filial son of piety unfailing. There shall forever be conferred blessing on you?”

***

Source:

- The Chinese Classics, translated by James Legge, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co. London, 1895

***