Contra Trump

… we need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. … America insists that you bear witness to it tripping on its dick and slamming its face into an uncountable row of scalding hot pies.

The Perth-based comic writer Patrick Marlborough made this observation in I Should Be Able to Mute America, published in July 2022. Although Marlborough’s arsey style delighted me, I readily confessed to myself how much I have always enjoyed the beguiling, challenging, repulsive, uplifting, self-obsessed and therapeutic cacophony of America. Nonetheless, Marlborough was on the money with this observation:

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. … America has effectively built a Green Zone in our cultural consciousness, replete with the obligatory Maccas. Our imaginations, memories, and selves have been well and truly occupied, and the schizoid psychic agony of mainlining our nation’s duel nightmares is, more often than not, excruciating.

Like many people of my generation, I grew up with America. My Scottish-Australian mother had worked for the American Navy during the Pacific War and was enamoured by the experience. At the end of the war her sister, my aunt Joy, married a Black sailor and they ended up running a bar in the Bronx, which my brother visited on his first trip overseas. My German-Jewish grandmother — my father’s mother — spent half a year every year in Forest Hills, New York, with her beloved twin cousins and my father frequently included a stop-over in the US while on his business trips to Europe and Asia. We played Cowboys and Indians in the garden; the Lone Ranger, Tonto, Jack Benny, as well as all of the bumptious members of The Mickey Mouse Club crowd my earliest memories of television. On one memorable birthday, dad set up a projector to screen Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy for me and my friends; then there were all of the times that my brother and I went to movie matinees where we enjoyed Elvis Presley, Vincent Price and a cavalcade of American stars camping it up.

I remember, too, exactly where I was — as well as my mother’s heartbroken sobs — when, on 23 November 1963 (a Saturday in Sydney — the 22 November was Friday in Dallas), we heard that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas. We mocked the slogan ‘All the way with LBJ’ announced by Prime Minister Harold Holt when he visited Lyndon Baines Johnson at the White House in 1966 and we followed with alarm the escalation of the conflict in Vietnam, since it also involved the conscription of Australian troops, as that might have included us. On 4 May 1968, my parents celebrated my birthday by taking me to see Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey and, in July 1969, my brother and I sat at our guru’s home ashram at Bondi Junction eyes glued to the telly as we watched the moon landing with our fellow would-be hippies. Why, in 1986, I even married an American!

The delights and the dramas of America are interwoven into the lives of three generations of my family. Our imaginations, memories and sense of self were partially enthralled by the American Other. You could even say that, for many like us, a kind of Stockholm Syndrome — perhaps an ‘American Derangement Syndrome’ even — is a natural condition, be it for weal or bane. This had long been the case, even without China.

***

In 1965 nine out of ten Americans couldn’t have spelled Vietnam’s name or found it on a map; but by 1968 Vietnam was a national obsession, and it split American society apart in what proved to be the most divisive and culturally ruinous conflict since the Civil War a century earlier. In the end, which came in 1975, after more tonnage of explosives had been dropped on Vietnam than on all Europe in the Second World War, fifty-eight thousand young Americans and countless Vietnamese were killed in a war that America lost. And such was the internal dissension over Vietnam—the riots and demonstrations, the furies unleashed by the rebellion of the young against their elders, the sense of a polity spinning off its axis and out of control—that America has not in any full sense recovered from it, thirty years later.

The annus horribilis was 1968, the year in which hope for a civil society seemed most imperiled: the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, the bloody police action against demonstrators in Chicago at the Democratic Convention, the riots of blacks in burning ghettos across America, from Watts to Detroit, seemed not only fearful in themselves but portents of worse to come. In many respects, however, 1968 now seems a time of relative sanity and security compared to the present. Campus bombings, for instance, were small and, in human cost, relatively harmless affairs beside the destruction of 168 lives by the truck bomb in Oklahoma City in 1995; the actual threat posed to civil society by the Black Panthers and other radical left outfits was slight compared to the proliferation of paranoid, armed, far-right militias today; and there was still a general belief in the capabilities of formal politics to deal with social problems, which seems to be dwindling, if not altogether dead, in the America of 1997.

Still, it was in the sixties that the consensus that had held America together for a hundred years came spectacularly unstuck. Because they are all, ultimately, immigrants, and so different in their origins from one another, Americans had always been quick to disagree but good at creating consensus. But they became less good at it after Vietnam, and the results are still with us: in mistrust of government, in the collapse of the Great Society programs, in the so-called culture wars between the politically and the patriotically correct, and in America’s disillusionment with its power to fulfill its own idealist promises. The cowboys were no longer the good guys. The Indians were no longer the savages. The nightmare of Vietnam cast America into an age of anxiety from which it has not yet emerged.

— Robert Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997, p.544

***

In 1993, when the art critic Robert Hughes, one of the best-known expat Australian writers of his generation, published The Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America, I was spending long stretches of time in Boston working on a documentary film about the Beijing Protest Movement of 1989. The author in 1986 of The Fatal Shore: the Epic of Australia’s Founding, a harrowing account of the British convict system, Hughes had lived in America for decades and his book, an outsider’s perspective on the cultural strife of his adopted homeland, was an unsparing critique of the present and a warning about the future. I had been reading Hughes since the 1970s and this new work immediately resonated with me. He noted ‘the sterile confrontation between the two PCs — the politically and the patriotically correct’ and told the reader that:

The fact remains, America is a collective work of the imagination whose making never ends, and once that sense of collectivity and mutual respect is broken the possibilities of Americanness begin to unravel. …

Throughout the 80s, this happened with depressing regularity on both sides of American party politics. Instead of common ground, we got demagogues. … Neo-conservatives who create an exaggerated bogey called multiculturalism — as though Western culture itself was ever anything but multi, living by its eclecticism, its power of successful imitation, its ability to absorb “foreign” forms and stimuli! — and pushers of political correctness who would like to see grievance elevated into automatic sanctity. …

The Culture of Complaint was a prescient work, published just as a new stage in America’s cultural agita and political dysfunction was unfolding. Hughes depicted the manichean struggle for America with trademark flair:

… some academics want a little slice of the action of spectacle provided by mass culture. Dazzled by its shine and yackety-yack, they are more groupies than rebels. The sequence is predictable. Ice-T or Sister Souljah do their raps about killing whitey, and call themselves “revolutionaries.” A CEO at Time-Warner, which distributed Ice-T’s exhortations to cop-killing, then defends the corporation’s right to produce such stuff in terms plangently reminiscent of Milton’s Areopagitica. After these pieties, scholars weigh in with learned papers on the revolutionary promise of sixteen-year-olds in the ‘hood. Up come the conservatives, wringing their hands in the manner of the late Allan Bloom over rap, rock-‘n’-roll, and the unearned Dionysiac ecstasies of mass multi-culti. Somewhere along the line the obvious fact that rap and hip-hop are not the agents of a desired or feared apocalypse, that they are just another entertainment fashion, gets lost. And it is lost because one side needs the other, so that each can inflate its agenda into a chiliastic battle for the soul of America. Radical academic and cultural conservative are now locked in a full-blown, mutually sustaining folie à deux, and the only person each dislikes more than the other is the one who tells both to lighten up. Such is the latest mutation of America’s Puritan heritage.

***

Seppos and Drongos

Patrick Marlborough is a self-described ‘neurodivergent nonbinary writer/ comedian/ musician/ drongo’ based in Walyalap (Fremantle), Perth, Western Australia. Marlborough’s work has appeared in VICE, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, Slate, The Saturday Paper and NME. In the essays reproduced below as part of our series Contra Trump 2024, Marlborough continues in a narky vein that has been mined by many other Australians over the decades. Like Robert Hughes before him, Marlborough vainly attempts to tell our American cousins simply to lighten up.

But, first, a linguistic note: ‘Seppo’ is an Australian slang term for ‘American’. It is a shortening of ‘Septic Tank’, a rhyming expression for ‘Yank’. ‘Drongo’ is an old term for a clown, fool, idiot or, as Seppos might put it, ‘a loser’. Marlborough uses drongo as a general term for Australians. As he puts it in Yeah, Nah (reprinted below):

Seppos will never get a handle on drongos, I reckon. That is to say: I don’t believe Americans will ever be capable of fully understanding Australians, Australian culture, Australian attitudes, or Australian thought. And why would they? Americans are American, which means they aren’t obliged to understand anyone, even themselves. That’s the beauty of their version of “freedom,” after all.

It is a sentiment that resonates, although perhaps not particularly sonorously, with what Robert Hughes said over three decades ago:

… one should indulge in neither the Cultural Cringe (the belief that nothing in Australian culture is worthwhile until it has been certified overseas) nor its defensively brash successor, the Cultural Strut, in which one marches up and down to the tune of Waltzing Matilda pretending that nothing made outside Australia is “relevant” to Australians. The right attitude is neither cringe nor strut, but a natural and relaxed uprightness of carriage.

***

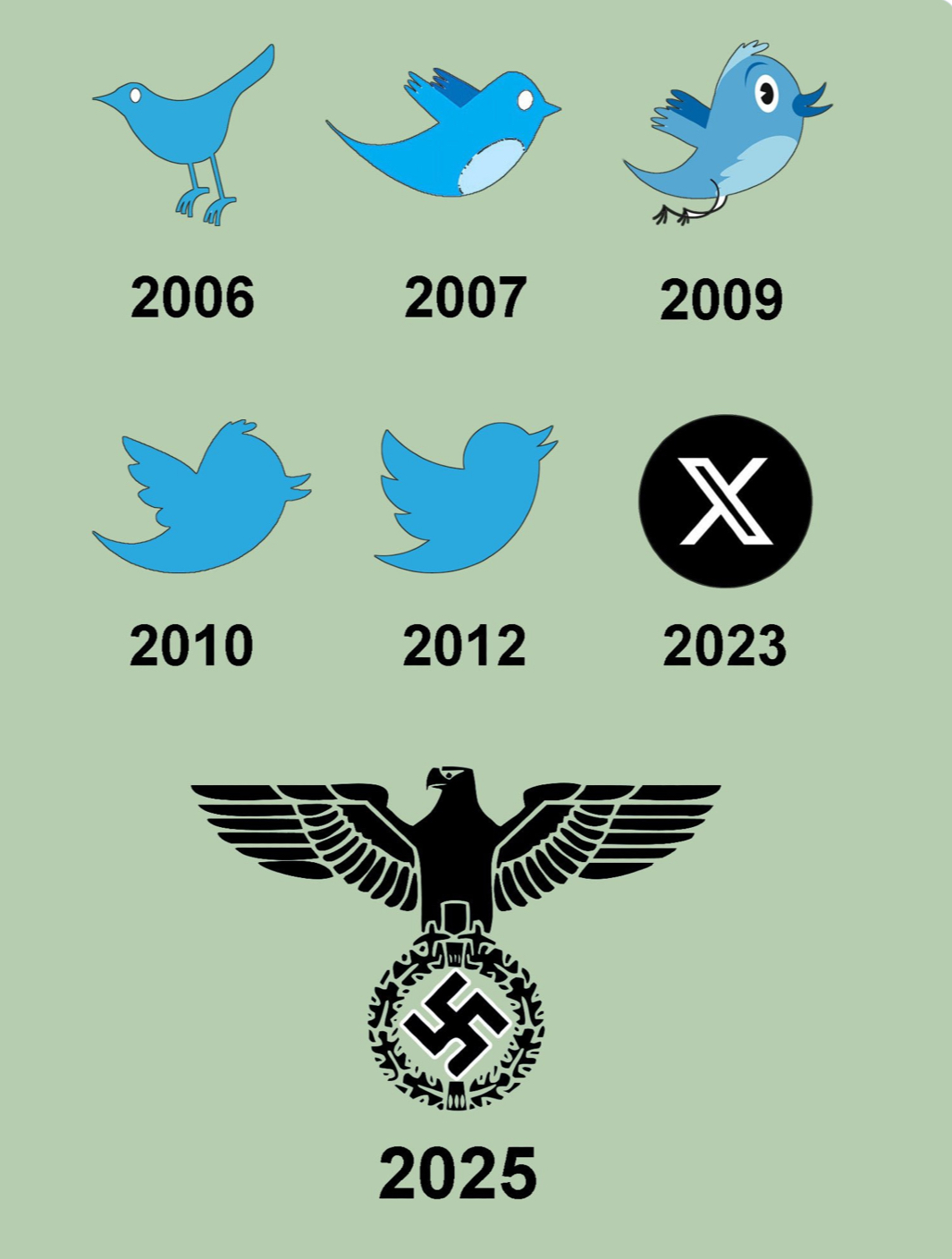

X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, features in this chapter in Contra Trump 2024. China Heritage registered a Twitter account in 2016 and it has been maintained ever since by Callum Smith, our webmaster. Elon Musk took control of Twitter in October 2022 and, in July 2023, it was rebranded as X (the domain name transitioned from Twitter.com to X.com in May 2024). Since then, Kara Swisher, the journalist of Burn Book: a Tech Love Story fame who featured in ‘You are garlic chives!’ — Trisolarans, Burn Book and China’s Men in Black, started referring to the site as a Nazi Porn Bar. Since the November 2024 presidential election, Swisher, like many others, has redirected her social media attention to other platforms. China Heritage has also signed up to BlueSky — see chinaheritage.bsky.social — although we maintain a presence on X, Nazis notwithstanding (see Trump Redux—Who Goes Nazi Now?).

Patrick Marlborough, aka Bang Bang Bart, can be found online at:

- @Cormac_McCafe (account suspended after Marlborough repeatedly suggested that Musk deserved a ‘final solution’ of his own

- https://cormacmccafe.bsky.social

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

22 November 2024

***

America’s Empire of Tedium

— Trump Redux 2024

- MAGADU — Kubla Khan, Xanadu & the 2024 American presidential election

- Waiting for the Barbarians in a Garbage Time of History

- Unless we ourselves are The Barbarians …

- What seeds can I plant in this muck?

- If you elect a cretin once, you’ve made a mistake. If you elect him twice, you’re the cretin.

- The Great Red Wall — A Remarkable Coalition of the Disgruntled

- A Political Monster Straight Out of Grendel

- Trump is cholera. His hate, his lies – it’s an infection that’s in the drinking water now.

- Trump Redux — Who Goes Nazi Now?

- An Elegiac Eulogy from Unf*cking The Republic

- The American Green Zone in Our Consciousness

- Rogue States — a Mao-Trump Ludibrium

***

I should be able to mute America

The rest of the world should not have to know the name Bari Weiss

Patrick Marlborough

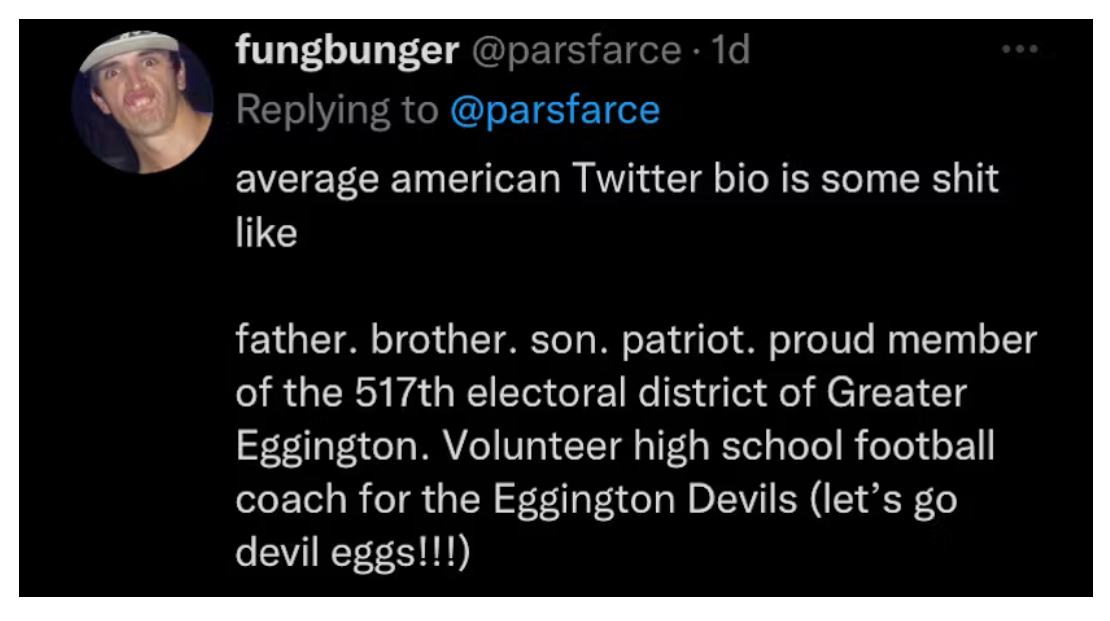

On June 2 [2022], Australian twitter account @parsfarce aka fungbunger (who has been referred to as Australia’s dril) tweeted out: “bloke at work who’s been here for like 6 years handed in 2 weeks notice last Friday & now he’s done the old Harold Holt. completely AWOL. managers goin off their heads. ghosting close work mates’ calls & texts. so fuckin good. the old scorched earth strategy for no fuckin reason.”

[Ed. Note: PM Harold Holt disappeared while swimming off the Victoria coast in December 1967. One theory held that he’d been spirited away by a Chinese submarine. See also Brad Esposito, An Interview With “Fungbunger,” The Funniest Man You’ve Never Heard Of, BuzzFeed, 28 October 2015.]

Australians joined fungbunger in celebration, a resounding chorus of you bloody ripper! and fucken oath, so good! and ol’ m8 livin the fucken dream! We were ecstatic, jubilant, and envious of what we recognized as a beautifully deft, and quintessentially Australian, act of get fukt dickheads, yeeeewwww!

If only we’d kept our joy private. If only we’d stayed humble! Instead, we caused the tweet to go viral and before we realized what was happening it drifted over to that foulest of places: American Twitter.

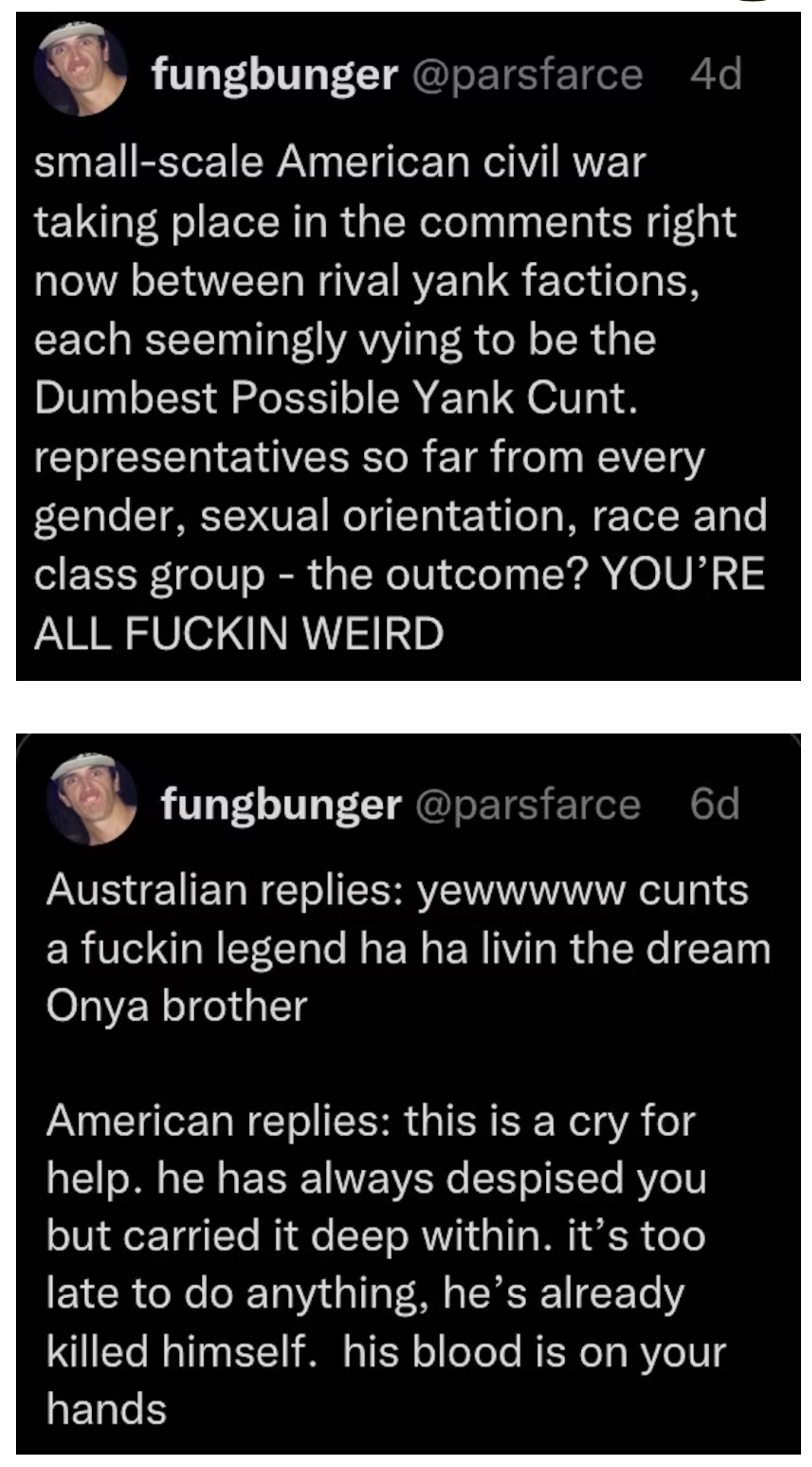

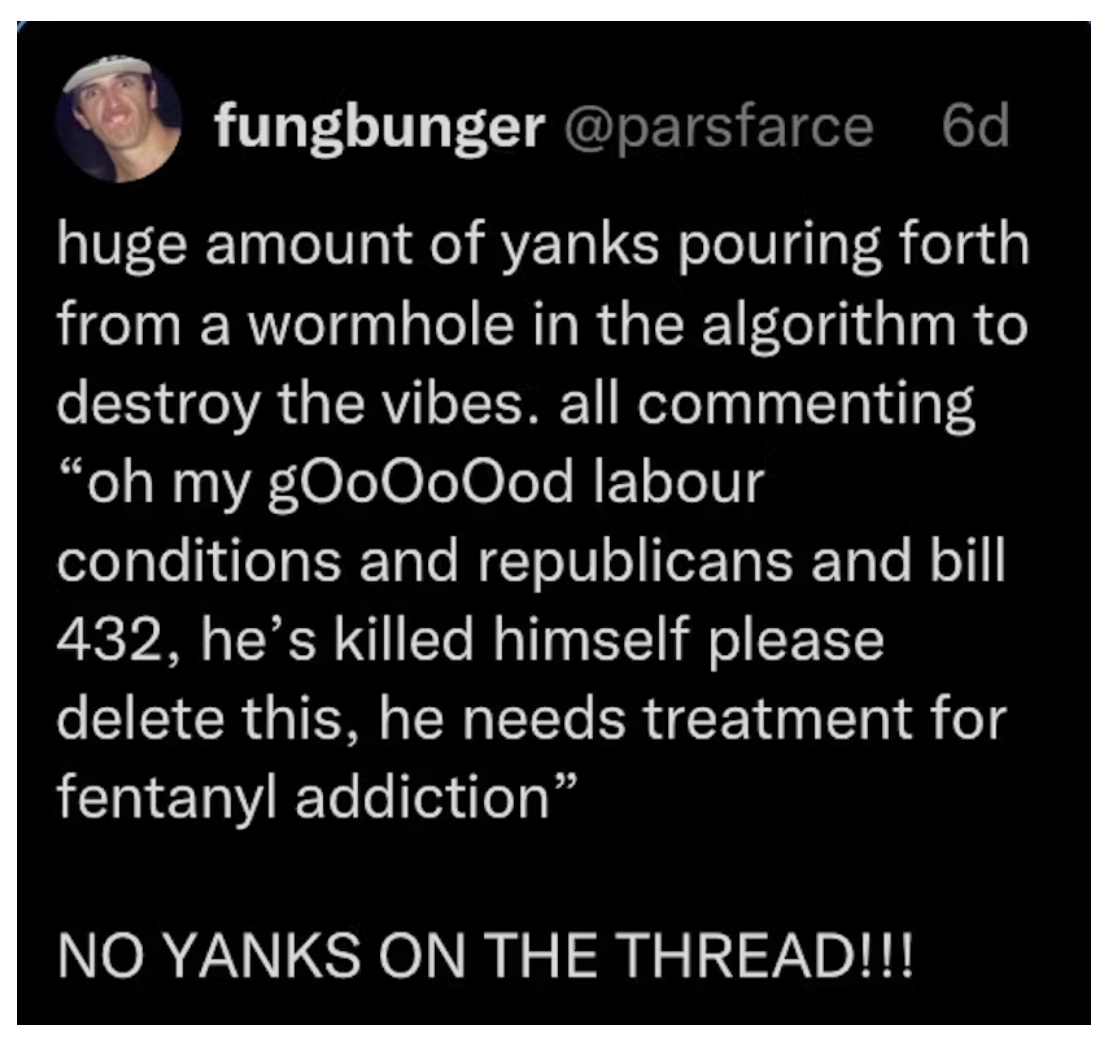

Soon, fungbunger was harpooned with replies from accounts with names like “PelotonMomForBiden,” “TeslaTerry,” and “JAGEnjoyer78.” They suggested that the man in question had killed himself, that he was a tortured soul, that this was actually the fault of our (their) failing healthcare system, that this was Governor so-and-so’s doing, that their wife’s friend had dramatically quit his job before shooting up the place, and so on. Worst yet were those boasting of how they had done something similar themselves, but in the grim, joyless way unique to residents of the 50 states.

Fungbunger plunged into his replies, laying waste to this plague of Americans like a bogan berserker.

“If this is to be my lot,” he tweeted, “an eternity of wrath, to slay the yank, to hunt its kind, then so be it. I shall walk into darkness and I shall cleanse it. I am the Yank Hunter.”

No yanks on the thread! came the rallying cry, NO YANKS ON THE THREAD!

For his courage, Twitter suspended fungbunger’s account.

The martyrdom of fungbunger has made it crystal clear in my mind: we need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. America is exhausting. America is incapable of letting something be simply funny instead of a dread portent of their apocalyptic present. America is ruining the internet.

America is the internet.

I’m a sandgroper from Perth, Western Australia, a place sometimes referred to as the most isolated city in the world. Perth is essentially one big gelatinous suburb with the temperament of a disgruntled stepfather and the drive of his dysfunctional failson. As such, it is a Facebook town.

But I am a Twitter tragic, tragically.

Australian Twitter is not unlike American Twitter in that it’s a collection of wonks and wankers who work in or around the arts, media, and politics. Because all our wonks leave for newspaper internships in Sydney, and our wankers leave to mount one-man shows in Melbourne, Perth Twitter contains the dregs and weirdos of Australia’s terminally online.

Being three hours behind the East Coast, late night Perth Twitter is a bit like the Night’s Watch in Game of Thrones: a rag-tag collection of rejects trudging along the great slippery ice wall of infinite scroll while the realm sleeps.

Unfortunately, this means that we’re the first to witness the awakening of that undead nightmare otherwise known as “American discourse.”

THE GREATEST TRICK AMERICA’S EVER PULLED ON THE SUBJECTS OF ITS VARIOUS VASSAL STATES IS MAKING US FEEL LIKE A PARTICIPANT IN ITS GRAND EXPERIMENT.

***

***

Before I sleep, I’m witness to many nightmares: Brooklynites are gutting each other over the sanctity of the bodega, Louisianan astro-poets are putting the wiccans to the torch because of their ongoing “amethyst erasure,” someone from Minnesota has gone viral claiming that it is an act of “class genocide” to know that drinking water keeps you hydrated, a Florida DSA chapter is publicly imploding over the contested value of feet pics, a Washington Post columnist is loudly pissing themselves over a petty workplace slight, the bassplayer from a long defunct hardcore band is begging people to share the gofundme page for a single mother made homeless by a twenty minute hospital visit, while armchair experts debate the value of mask mandates as #1milliondead and #bidenbts trend in your sidebar.

America insists that you bear witness to it tripping on its dick and slamming its face into an uncountable row of scalding hot pies. You do more than bear witness, because American Twitter has the same kind of magnetic pull as a garbage disposal unit. A sick part of you wants to shove your hand in. You want to let the blades cut into your knuckles, if just to see if you can slow them down a little.

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. My generation in particular is the first pure batch of Yankee-Yobbo mutoids: as much Hank Hill as we are Hills Hoist (look it up!), as familiar with the Supreme Court Justices as we are with the judges on Master Chef, as comfortable in Frasier’s Seattle or Seinfeld’s Upper West Side as we are in Ramsay Street or Summer Bay.

America has effectively built a Green Zone in our cultural consciousness, replete with the obligatory Maccas. Our imaginations, memories, and selves have been well and truly occupied, and the schizoid psychic agony of mainlining our nation’s duel nightmares is, more often than not, excruciating.

I should not know who Pete Buttigieg is. In a just world, the name Bari Weiss would mean as much to me as Nordic runes. This goes for people who actually might read Nordic runes too. No Swede deserves to be burdened with this knowledge. No Brazilian should have to regularly encounter the phrase “Dimes Square.” To the rest of the vast and varied world, My Pillow Guy and Papa John should be NPCs from a Nintendo DS Zelda title, not men of flesh and bone, pillow and pizza. Ted Cruz should be the name of an Italian pornstar in a Love Boat porn parody. Instead, I’m cursed to know that he is a senator from Texas who once stood next to a butter sculpture of a dairy cow and declared that his daughter’s first words were “I like butter.”

The irony is that so much of the rot at the heart of American discourse stems from a media empire founded by an Australian (Steve Irwin!!! [haha just kidding, it’s Rupert Murdoch]), and for that I apologize — you can take comfort in the fact that he’s stunk this place up like a backyard dunny too. But it would be great if we could stem the flow of poison that America sends our way, seeping, as it does, from that proverbial septic tank.

My nation’s finest lackwits have spent the better part of their lives trying to graft America’s culture wars onto our own. Just last week our new Opposition Leader Peter Dutton (imagine a young Barry Goldwater spliced with a mall cop and an orc) tried to get the “teachers are dangerous radicals” thing going here, right on the heels of his party crashing and burning in the recent federal election, alongside their version of American (and British, to be fair) electoral transphobia.

Oftentimes, it just seems easier to submit to the Americanization of self, nation, and internet — to meekly roll over and spell it “jail” instead of “gaol,” as in “the Seppos locked fungbunger up in twitter gaol.” Why fight the inevitable?

This is why funbunger’s thread was as cathartic as it was inspiring. There he was, pushing back against the American sensibilities that crawl their way into every last crevice of the internet, despite the platform, the users, and the algorithms insistence that he bend to them. A dial-up Breaker Morant staring down the barrel of a perma-ban and barking: oi you dog cunts, shut your Seppo gobs!

***

Source:

- Patrick Marlborough, I Should Be Able to Mute America, Gawker, 16 June 2022.

***

***

Lament of a Person with Autism

Patrick Marlborough

Where the not-too-distant internet of yore not only fostered but encouraged the kind of idiosyncrasies that autistics tend to have in spades, the internet of Elon Musk, Zuck, and whatever malevolent vulture capitalist is sure to one day buy and gut this website, is one with little time or room for the unclickably peculiar and difficult—not being trending-page friendly, we tend to be hard to make a buck off (unless a majority of your advertising revenue comes from companies like Bandai or the New York Review of Books). What spectrum-lite oddness persists is part run-off, part fluke, part carnival barker—the most vocal autistic voices operating somewhere between vaudevillian and huckster, thriving in that great medicine show that is the front-facing camera video circuit.

This lament is tired by now, but of all the social media platforms, losing Twitter hurts the most. The site now known as “X” was always the one with the most visible (and visibly) autistic community, and the one that ran on the most visible autistic logic: recursive, hyperactive, cumulative, hopscotched, and interlinked. It is a site built on the backs of the obsessive, the passionate, the goofy, the gullible, and the confused: a place where autists could disappear into the crowd while, perhaps, finding comfort in the innately illogical logic of Twitter’s shonky and digressive conversations—that intersection of fandom and weirdness and euphoric shitposting. For a time, the site achieved what I think “peak internet” can achieve when it’s at its best: the ability to make autistics of us all.

Under Musk—who, ironically, is autistic—it has more or less ceased functioning, like me at a rave with a strobe light. Musk, one could argue, is the final boss of toxic, autistic forum moderators: an isolated, awkward exile, vengefully venting his frustrations with his indelible himness by burning holes in the community he reigns over, like a self-anointed champion citing made-up rules before upturning the table at a Magic: The Gathering tournament. Twitter already felt like a place for autistic exiles and refugees from that old internet, functioning as a holding pen or zoo enclosure for an endangered species made migratory by circumstance, if reclusive by nature. For those of us tragically linked to Musk, that googoots soyjak, by diagnosis (and perhaps loneliness), his flipping of said table has left us adrift and grasping, bereft of what we once briefly thought of as ours.

— Twitter, blogs, and forums used to be a haven for people with autism. Not anymore., Slate, October 2023

***

Yeah, Nah

Seppos will never get a handle on drongos, I reckon. That is to say: I don’t believe Americans will ever be capable of fully understanding Australians, Australian culture, Australian attitudes, or Australian thought. And why would they? Americans are American, which means they aren’t obliged to understand anyone, even themselves. That’s the beauty of their version of “freedom,” after all.

Aussies, meanwhile, are up to our bottom lip in American culture, philosophy, politics, and—let’s call it what it is—psychosis from day dot, to the point where we’re both drowning in and drowned out by it. Your everyday drongo can parse, speak, and think seppo—maybe even pass themselves off as one, if they round out their vowels enough. For many Australian artists dreaming of making it big (or just making any money at all), to become American is to become powerful, heard (loud), omnipresent, and, most importantly, unashamed. This is the heady pipe dream of many an Aussie wanting to surpass the stunted heights offered by our flailing culture industry.

But even if this transformation is achieved, granting a ticket of leave from our roots, the fair-dinkum fact of our Australianness—our internal, eternal, undying drongo—can never be erased. There remains a crucial, seemingly irreconcilable difference between the two cultures: Americans are sincere to a fault, whereas Australians are insincere to a fault.

This distinction is crucial to understanding Hannah Gadsby, the Australian non-comedian who drew acclaim for their live stand-up turned Netflix special Nanette in 2018, and more recently derision for their new art exhibition, “It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum.

The exhibition consists of a small collection of Picasso’s work highlighted with Gadsby’s commentary and so-called jokes, as well as a seemingly random collection of works by female artists taken from the museum’s collection. “It’s Pablo-matic” is pitched as a denunciation of the man himself, his misogyny, and the misogynistic forces of history that elevated his genius. It is the manifestation of a call-out post, if one that’s one degree of separation from the Sacklers.

Since “It’s Pablo-matic” opened in early June, American critics from hallowed American institutions like the New York Times have torn Gadsby apart for the show’s apparent philistinism, condescension, and smug self-assuredness. Times critic Jason Farago, in one buzzy pan, wrote of the exhibition, “There’s little to see. … The ambitions here are at GIF level.”

Those critics may be right in their barbed assessments, but they are missing a fundamental piece of the puzzle: the innate Australianness at the center of Gadsby’s work and philosophy.

To make sense of this, allow me to explain the Australian cultural phenomenon that is the elegantly simple “yeah, nah.” For the baffled seppo: “Yeah, nahhh” is Aussie slang that essentially means “I understand, but I disagree.” Despite our reputation as pissed-up, muscle-bound brawlers, Australians are, at our core, an incredibly passive-aggressive people who prefer waving someone or something away over sucker-punching or shooting it. “Yeah, nah” embodies our reflexive dismissiveness of anything that we find even mildly disagreeable. Conversationally, it’s a neat little tool that lets you wave away the paranoid rantings of a black-pilled Facebook uncle, or skirt around a stranger at a bush doof who is insisting you try their “home-brewed black acid”; it’s also just a nice way of saying “you’re fine, ay” without causing offense.

Where seppo language and thought can be block-lettered, cemented, and literal, Australia’s is scratchy, mercurial, and tricky. I like to think of it as Americans thinking and talking like kazoos, and Australians thinking and talking like slide whistles. Drongo thinking can be so slippery that it passes through our own grip on it, so something as seemingly innocuous as “yeah, nah” can suddenly go from being a stock response to a poly couple seeking a unicorn on a dating app to a kind of internalized dismissiveness of society, culture, and life at large. Any idea that gets your goat, even slightly, can be swept away with a simple, subliminal slap of the big “YEAH/NAH” button that all Aussie drongos carry everywhere with us in our heart of hearts.

At the root of all this is something known as the “cultural cringe.” Coined by critic A. A. Phillips in a very cheeky essay in Meanjin (fantastic Aus lit journal, check it out) in 1950, the “cultural cringe” refers to the belief that your own national culture is inferior to that of other countries. In Australia, this originally manifested as a desperation to appear British, which eventually transformed into a desperation to appear American once your mob took over—a desire that social media and the ever-darkening shadow of U.S. global imperialism has rabidly fueled over the years.

For Australia, a country with about as many inferiority complexes as one that largely owes its existence to an orgy-loving occultist naturalist could have, the natural endpoint of cultural cringe is a distrust of culture at large, as the very idea of it—cinema, theater, literature, high art—has been made to feel, essentially, un-Australian. As a people, we tend to have a knee-jerk “yeah, nah” response to the very idea of “the arts” in general. Probably since the first British marine painted the first convict deported to Port Jackson for public exposure, Australians have seen art as something solely for “wankers.” And if there are two things that Australians are paranoid about being perceived as, it’s wankers or poofters. Art, to our unending terror, has the whiff of both. This paranoia has been the major motivator behind much of our culture and history, and was why the man who wrote the poem that became our unofficial national anthem, “Waltzing Matilda”—our Walt Whitman or Mark Twain, if you will—decided to take up the pen name “Banjo” (+5 wanker points, −65 poofter points).

We are a people whose love of making fun of everyone and everything—I’m sure I’ll be accused of perpetuating “tall poppy syndrome,” or tearing down someone who has found great success, for this essay—is only outweighed by our rabid hatred of being made fun of. Australians are naturally suspicious of art and its challenging ambiguity; by merely existing, it is often perceived to be mocking us.

This is the drongo undercurrent of Hannah Gadsby’s work—of everything that has culminated in “It’s Pablo-matic.”

Back in 2018, when Nanette fever was sweeping the world and Gadsby was performing the show on Broadway, I was living above a glue factory in Bushwick. I made several attempts to watch Nanette, but a combination of apathy and a lapsed Vyvanse script made this all but impossible. I eventually caught the majority of it when my roommate’s girlfriend played it on our loft’s wall via our projector. The only part that made me laugh was Gadsby’s riff about Picasso. This wasn’t because I found the jokes funny, or because their ideas created “the tension” (as they put it) that necessitate a laugh, but because Gadsby sounded like any one of the firmly middlebrow “Art is for pooftas” drongos I had left back in my hometown, the famously culture-phobic Perth.

In this notorious part of Nanette, which Times critic Farago describes as Gadsby “most bizarrely” condemning art as “an elite swindle,” we see a perfect distillation of Australia’s antagonistic relationship with art and culture as a whole. When I watched Gadsby mockingly enunciate “CUUUUU-bism” while mugging and rolling their eyes for a delighted Sydney audience, I was dumbstruck by sudden-onset homesickness. When I heard them say that Picasso just “put a kaleidoscope filter” on his penis to think up Cubism, I was instantly taken back to Australia’s public school system, where the failed artists turned substitute teachers had an ax to grind against anyone suspected of thinking themselves superior to that lot (I have vivid memories of a teacher who talked about Andy Warhol like he’d murdered the guy’s family).

“It’s Pablo-matic” shares this dropkick drongoism with Nanette. But what makes both performances special is their touch of seppo. In what may be the most successful merger of Australian and American culture to date, Gadsby deftly melds Australian insecurity with American certainty. Gadsby’s work sits at the intersection of Australia’s reflexive anti-intellectualism and America’s corporatized identity politics. Both phenomena find a common ground in the middlebrow, the natural resting place of attitudes that find anything outside their comfort zone suspect, degenerate, or both. Armed with the overbearing sincerity that allows American critics and commentators to function as culture cops—categorizing and cauterizing art so that it can be decried and denounced without the hassle of serious interrogation—Gadsby is able to equip their quintessentially Australian view of art as snobby rubbish with an identity-wrapped crutch that doubles as a bludgeon. In Nanette, they conflate Picasso with Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump. In “It’s Pablo-matic,” they write “weird flex” next to a Picasso print of a nude caressing a sculpture of a naked hunk, and their and the Brooklyn Museum curators’ response to criticism of the exhibition was to delight in getting “(male) critics’ knickers in a twist.”

The end goal is the same: to take this thing that angers or disquiets you, stamp it as “toxic,” shrug at it, and sweep it aside.

Australian culture is always five to 10 years behind the rest of the world, which is why someone like Gadsby, with their stuck-in-the-2010s sense of humor and social issues, can thrive stateside: They’ve drifted in from a lagging parallel timeline, as entrancing (in a ’50s-themed diner sort of way) as they are confusing to contemporary American critics. To those critics, “It’s Pablo-matic” may be an abomination, but I see it as something closer to a miracle of seppo–drongo relations, a perfect merger of American sincerity and Australian insincerity. Gadsby has managed to invert, export to the American market—the only market that matters—and profit from Australia’s cultural cringe and fear of “the wanker.” In doing so, Gadsby has blessed America with a slither of Australian enlightenment: that beautiful little head tilt and wave-off known simply as the “yeah, nah.” The fact that that seems to overwhelmingly be the critical response to “It’s Pablo-matic” is, in its own way, art.

***

Source:

- Patrick Marlborough, Yeah, Nah, Slate, 10 June 2023

***