Translatio Imperii Sinici

I find you here …

Blindly recreating

A black dream-hole of history.

— P.K. Leung

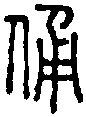

On 1 July 2017, China Heritage marked the twentieth anniversary of mainland China extending suzerainty over Hong Kong with a series of translations, commentaries and art works. We started that series with ‘Cauldron’ 鼎, a poem by the celebrated Hong Kong writer Leung Ping-kwan (梁秉鈞, 1949-2013, also known as P.K. Leung and Yasi 也斯, his pen name).

P.K.’s ‘Terracotta Warriors on the Rhine’ 萊茵河畔的兵馬俑, translated into English by John Minford, is the latest chapter in China Heritage 2019, the theme of which is Translatio Imperii Sinici. As ‘Cauldron’ 鼎 also resonates powerfully with the theme of the imperial, it is reproduced below. In this vein, we also recommend ‘The Great Palace of Ch’in — a Rhapsody’ 《阿房宮賦》 by the Tang-dynasty poet Du Mu 杜牧 and translated by John Minford.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

18 April 2019

A Note on Translatio Imperii Sinici

China’s First Emperor (始皇, Ying Zheng 嬴政, r.220-210 BCE), as well as what is known as ‘The Rule of the Qin’ 秦制, a shorthand expression that has long been used to characterise tyrannical government, frequently feature in China Heritage. The autocratic mindset and habits of China’s past, as well as the shadow that they cast over the People’s Republic today, are of particular concern to writers like Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, whose work has been appearing in these virtual pages since 1 August 2018.

As we noted in our description of Translatio Imperii Sinici when introducing China Heritage Annual 2019, the concept of ‘Empire’ has enjoyed renewed debate among historians and political scientists for over a decade, and it has featured in our own work since the launch of China Heritage Quarterly in 2005 and through our advocacy of New Sinology 後漢學.

In Drop Your Pants!, our five-part series on the Communist Party’s 2018 patriotic education campaign, we discussed the creation in the 1920s of the Chinese party-state 黨國, a Nationalist-era term revived in recent years to describe the People’s Republic. We also introduced the journalist Chu Anping’s observations on Party Empire 黨天下, a word he used to describe holistic Party control and one that re-entered China’s political vocabulary as a result of the investigative historian Dai Qing’s study of Chu, and China’s suppressed liberal political traditions, in 1989.

In light of developments during the first years of the Xi Jinping era (2012-), the political scientist Vivienne Shue has suggested the importance of discussing ‘the Sinic world’s singular experience of empire, imperial breakdown, and passage to political modernity’. Once more, it seems pressingly relevant to investigate the country’s 國體 — an ancient term revived for use in nineteenth-century Japan and subsequently ‘re-imported’ to China when thinkers were debating the nature of dynastic or, for that matter, post-dynastic government. 國體 is not merely about formal governance or the system of rule, or indeed limited to the ideological underpinnings of the state, it is also used to indicate ‘national essence’, that is those things which constitute a ruled territory, its mores and imagination, its identities and cultures, in fact, its total existential presence. In an essay titled ‘Party-state, nation, empire’, Shue asks: ‘What light … can reexamining China’s oddly intact transfiguration — from dynastic empire to people’s republic — shed on how the Party has governed since 1949?’

In China Heritage Annual 2019 we aim to contribute to this line of inquiry, although our interests range beyond the immediate academic concerns of political scientists. While mindful of the yearnings, or at least nostalgia, for empire redux in such diverse modern polities as Erdoğan’s Turkey, Putin’s Russia, Modi’s India and Abe’s Japan, as well as however one manages to characterise the United States of America under Donald Trump, we would posit that Translatio Imperii, is no recent fad in China; indeed, it has been unfolding since the Taiping Civil War (1850-1864) and the Tongzhi Restoration (同治中興, 1860-1874, also known as the Self-strengthening Movement). It reached a significant contemporary moment in 1997 when Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin used the old Qing dynastic-era expression — ‘restoration’ 中興— to describe the post-1978 and post-1989 restoration of his regime’s fortunes. Our concerns, therefore, are not merely with the incipient ‘Red Empire’ of the Xi Jinping era — something discussed at length by Tsinghua Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 — but also with the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which still powerfully influence the Chinese world, and will continue to do so.

P.K.’s ‘Terracotta Warriors on the Rhine’ gives voice to the poet’s unflinching encounter with a dark legacy.

Note:

- This poem appears in Translatio Imperii Sinici, as well as in the sections Nouvelle Chinoiserie and The Best China featured in China Heritage Projects.

In 1974, farmers in Lintong county not far from Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province 陝西省臨潼縣, discovered evidence of what turned out to be an army of terracotta warriors, horses, chariots and military equipment made as funerary objects that were buried in serried ranks in pits at the site of the tomb of the First Emperor. Since an initial exhibit in Melbourne in 1982, the ‘Terracotta Army’ 兵馬俑 has become arguably the most readily recognised symbol of China. For some, the vast array of ancient cultural artifacts is sullied by its associations both with Qin tyranny and Mao-era terror.

— GRB

***

Terracotta Warriors on the Rhine

萊茵河畔的兵馬俑

Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉鈞

Translated by John Minford

I thought to see you here

On the banks of the Rhine

Standing proudly to attention in the rain,

Lonely soldiers sent to guard distant frontiers,

Yearning for distant homes and the embraces of your wives.

Instead I find you here

In this lakeside park,

Surrounded by tawdry bunting,

Dragon-and-phoenix flags,

Huddled together in marquees,

Blindly recreating

A black dream-hole of history.

Lost in sombre unsmiling reflections,

Anger and indignation

Suppressed, dissipated, transformed

Beneath a gloomy

Carapace.

Excavated after long centuries of history,

Each of you no doubt once an individual,

But now to foreign eyes

No more than a host of

Expressionless Chinamen.

Your Emperor’s ambition,

His fear of being alone,

Froze you, buried you

In his chosen space.

Could you ever really breathe down there,

Could you hear the sea?

A blonde-haired girl passes by,

Looks you up and down,

Glancing at your broken left arm.

You’d never be able to understand

Her gentle wiles,

Her soft beguiling words.

How clumsy you are

In these civilised surroundings!

No words can hope to trace

Your twisted tale,

No words can tell

Your history,

So much bloodier than theirs –

A longer catalogue

Of famines and disasters!

And your Emperor,

Who buried so many men of letters,

So many books,

Who was so much more ruthless

Than theirs ever was.

You ancient lumps of clay!

You terracotta puppets,

Standing dumbly in expectant rows –

A product line awaiting

Market appreciation!

Go home!

Let your ghouls and monsters

Take you home!

You have no place here,

On the banks of this river,

In this land of fine wine.

You’ll never set in motion

A bloody revolution here!

Those swords in your frozen hands

Will never pierce men’s hearts here!

The gentle breeze

Wafting from the riverbank,

Will never heal your hearts,

Crushed and broken

Time and again!

The rays of the sun will never melt

The cruelty of your history,

Sealed fast so many thousands of years

In its deep mental tomb.

萊茵河畔的兵馬俑

梁秉鈞

原以為你們會在萊茵河畔

在微雨中肅穆地排開站崗

放逐到邊界戍守的寂寞士兵

懷念遠方家鄉妻子的臂彎

今日我來這兒尋找你們

卻尋見了繪畫龍鳳的旗幟

眾生擠在湖畔公園帳篷裏

夢想重塑一個千年的墓穴

你似在沉思,你收斂了笑容

許是把憤怒或激昂轉化

成一點淡淡的凝重

你的執著成了黏肉的盔甲

葬入深遠的歷史又再挖掘出來

不能說沒有各自的神貌

但是在異鄉觀看的眼中

怕都只是沒甚麼表情的中國人吧

由於帝王的野心,由於他恐懼

寂寞,把你們凝止在這樣一個空間裏

埋入泥土,你可更認識空氣

在墓穴裏,你可更清楚聆聽海洋?

金髮女子目光來回的掃視下

你的左臂粉碎了,你不理解

溫柔的戰略,那些婉轉的言詞

禮貌的周旋裏你顯得何等笨拙

沒有語言能夠敘述這些扭曲,難道可以

誇耀你經歷的歷史比別人更加血腥

說你有更多的飢荒與災禍,你的帝王

比別人埋葬更多儒士和書本?

遠古的赤泥塑成待價而沽的玩偶

連魅魉帶回家去。在佳釀的異鄉河畔

你會突然策動一場血腥的叛變嗎?

僵持的手有日會把刺刀戮向誰的心臟?

從河邊吹來的和風

可會熨貼你重重挫折的胸懷?

心中重重陵墓中扣藏的千年暴戾

可會有一日在陽光下融化?

Cauldron

鼎

Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉鈞

As the Zhou Dynasty rebuilt the Empire

and celebrated the unity of All-Under-Heaven,

courtiers were honoured, ceremonial music composed

metals melted, vessels cast, new injunctions set in bronze,

power revalidated.

The grand banquet commenced, noblemen and elders took the

places of honour;

while savage fauna bubbled restlessly in the cauldron,

a sober phoenix motif replaced the gruesome mask of the Beast.

Our humble bellies have ingested a surfeit of treachery, eaten their fill of history, wolfed down legends —

and still the banquet goes on, leaving

an unfilled void in an ever-changing structure.

Constantly we become food for our own consumption.

For fear of forgetting we swallow our loved ones,

we masticate our memories and our stomachs rumble

as we look outwards.

Creation’s aspirations are trussed,

caught tight by the luminous bronze.

In his campaign against the Chu, the southern state,

as the Emperor approached the wilderness beyond the Central Plain,

ten thousand bawled for the rustics beyond the pale,

to make their low bow of homage;

stone and metal engraved; vessels fashioned; tintinnabulations of history.

The proclamations sit heavy on the stomach,

destroy the appetite;

the table is altogether overdone.

May I abstain from the rich banquet menu,

eat my simple fare, my gruel, my wild vegetables,

cook them, share them with you?

Is there a chance

your pomp and circumstance could ever change,

evolve

slowly

into a new motif,

some new arabesque

of beauty?

— Translated by John Minford and Can Oi-sum

***

Note:

- This translation previously appeared in ‘Banquets of History’, the concluding chapter in Geremie R. Barmé, The Forbidden City, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univeristy Press, 2008, pp.190-191. China Heritage has also published P.K.’s poem ‘Leaf Contact’ 連葉, accompanied by the photographic work of Lois Conner.