Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter IV, Part I

1984年

We may well claim that the hair-raising world depicted in this novel has, fortunately, not yet been fully realised in our own, but there is no guarantee that it won’t be in the future. We should guard against the possibility that in, say 1994, or perhaps at some other point, it won’t be visited upon us.

I quoted these lines from the translator’s introduction to George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eight-Four in a publication note that I wrote for The Nineties Monthly, a Chinese-language current affairs journal in Hong Kong, the year after 1984.

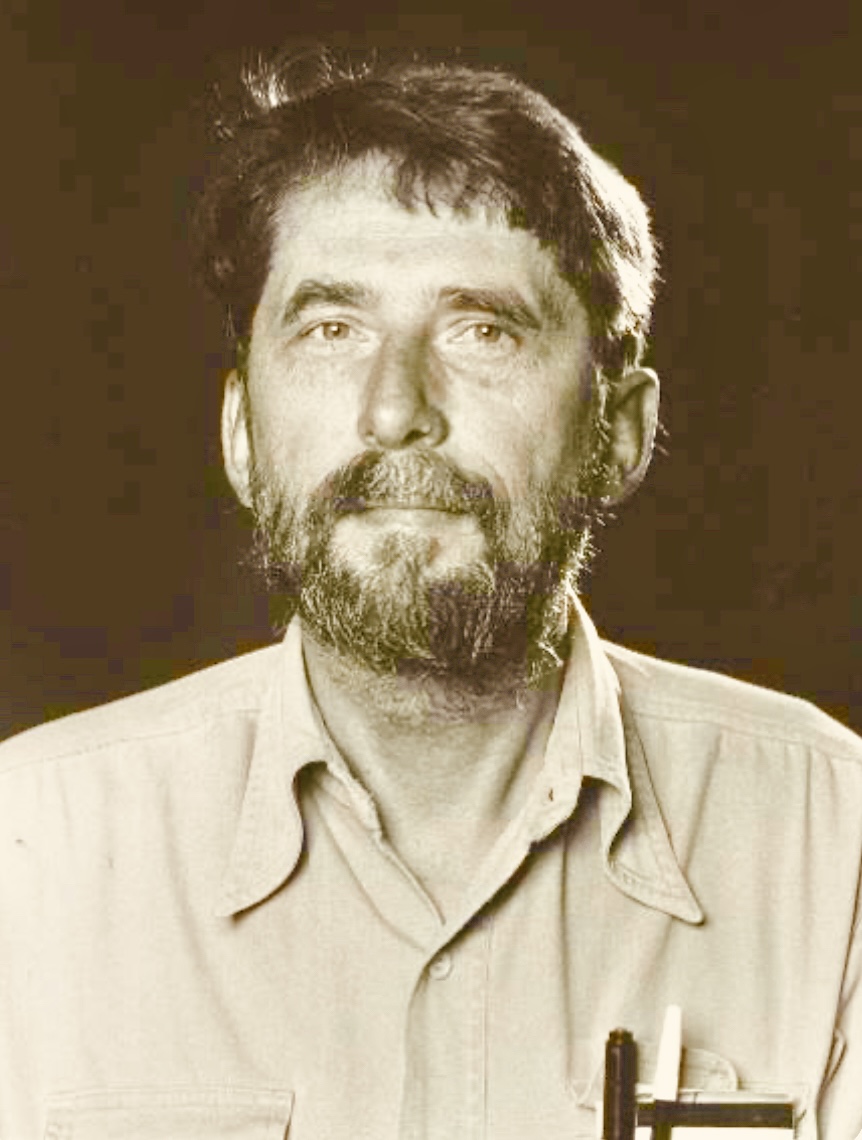

They were written by the translator Dong Leshan (董樂山, 1924-1999), a highly-regarded scholar and literary figure in Beijing. Gladys and Yang Xianyi, the Chinese-to-English literary translators I met in 1976, introduced me to Dong during the early heady days of post-Mao culture. I soon learned that he was one of the most prolific translators of modern China, his corpus included William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Edgar Snow’s Red Star Over China, The Humanist Tradition in the West by Alan Bullock, as well as Bullock’s seminal Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. He also translated The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972 by William Manchester and Isaac Stone’s The Trial of Socrates, which was published shortly before Dong’s death in 1999. Except for Manchester’s tome, many of these books had been a feature of my own adolescent reading history (I read Stone when it was published in 1989) and I was delighted to follow up Gladys and Xianyi’s introduction. I also learned that Leshan was the younger brother of Timothy Tung (董鼎山, 1922-2015), a member of the New York literary scene and a prolific contributor both to The Nineties and its predecessor, The Seventies Monthly, a journal edited by Lee Yee 李怡 under whom I had my literary apprenticeship, from 1977 to 1979.

I read Dong Leshan’s translator’s introduction to Nineteen-Eight Four as soon as he gave me a copy and we had one of those bitter-sweet discussions about the absurdity of it: China had only recently experienced the three-decade-long nineteen-eighty four of Big Brother, Newspeak and Doublethink and Facecrime. For two decades Leshan himself had been, to use Orwell’s expression, an Unperson, first denounced in the Anti-Rightist Campaign launched by Mao and stage-managed by Deng Xiaoping in 1957 and again during the decade-long Cultural Revolution. Now, despite the fact that the Communist Party was pursuing economic reforms, Leshan, like most of my older friends at the time, was wary of the lingering power of Maoism. They also knew the inescapable truth of one of Orwell’s most famous lines:

Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

***

The Chinese translation of Nineteen Eight-Four had originally been published during the tentative post-Mao cultural efflorescence of the late 1970s, although in a ‘restricted circulation’ edition. Leshan told me that despite the small print run and the fact that access to the book was supposedly limited to members of the political and academic nomenklatura, its instant popularity within the Party elite made it as widely read as any best seller of the day. Later, Huacheng Publishers in Guangzhou took advantage of their relative distance from Beijing to reissue the translation as part of a ‘dystopian trilogy’ 反烏托邦三部曲 that included Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World and We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, also translated by Dong Leshan, as was George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The ‘trilogy’ was also ‘restricted access’ and it was not until 1988 that Dong Leshan’s Nineteen Eight-four was reprinted for the open market.

[Note: For George Orwell’s review of Zamyatin’s We, see the postscript to ‘You are garlic chives!’ — Trisolarans, Burn Book and China’s Men in Black, China Heritage, 20 April 2024.]

I went to see Dong Leshan again in early 1984, this time to deliver a copy of ‘Orwell: The Horror of Politics’ by Pierre Ryckmans. Pierre, who had been my Chinese teacher in the early 1970s and was now my doctoral supervisor, had published his lengthy reconsideration of the English writer a few months earlier. It was the English version of a tract originally written in French. Pierre’s biographer explains the background to the essay in the following terms:

Deploring the fact that that great intellectual, for want of necessarily being a great writer, was largely unknown, or misunderstood, in France (maybe because of the ‘incurable cultural parochialism of that country’), he endeavoured, in seventy pages, to restore the diversity of Orwell’s oeuvre, focusing on certain books (Animal Farm, which Orwell considered his best book, and Homage to Catalonia), but especially on essays (most have remained unpublished in France) and extracts of correspondence. By also tracing the personal itinerary of a man who converted to socialism the way you embrace a religion, who came up against the most terrible realities (the suffering he endured in the boarding school he was sent to, the poverty in the industrial world of the North of England where he led his investigation, the miserable jobs of the British Empire in Burma, where he served in the colonial police, the murderous outbreak of fascism in Spain, where he fought), who strove no matter what to believe in the possibility of a victorious revolution (the sworn enemy of Soviet totalitarianism actually kept his faith in socialism right to the end) — Leys meant to underscore the fact that, with Orwell, the man and the work met and merged.

Pierre had read Orwell as a teenager but then, as his biographer notes:

He read him more assiduously after his experience in China. ‘Orwell seems to me to be a very profound reading guide in understanding China even though he never dealt with it’, he told Pierre Boncenne in 1983. ‘Paradoxically, his writings are more applicable to China than to the Soviet Union: the totalitarian project was most successful there, with the Chinese also being victims of the very refinement of their civilisation and of their highly subtle cultural equipment’. Already, in Chinese Shadows, he had claimed that ‘without ever dreaming of Mao’s China, Orwell succeeded in describing it, down to the concrete details of daily life, with more truth and accuracy than most researchers who come back from Peking to tell us the “real truth”.’

— Philippe Paquet, Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds, trans. Julie Rose, Black Ink Boosk, 2017, pp.413-415

Pierre ‘gleefully showed that the certainty that filled Orwell was “the very simplicity of the child who sees that the Emperor is naked”.’ Indeed, by then Pierre enjoyed renown in the literary and academic circles of Beijing for The Chairman’s New Clothes, his remorseless critique of the Cultural Revolution published in 1971 and surreptitiously read in Beijing even before Mao’s death.

In the days before I visited Leshan in the east of the city, I had delivered copies of Pierre’s essay on Orwell in the west, including to Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書 and Yang Jiang 楊絳, a couple who were emerging as post-Mao literary giants. As I noted in a review-essay of Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds, Philippe Paquet’s biography of Pierre:

When I met them in 1981 they immediately asked about my teacher, Li Keman (Pierre’s Chinese name). “He spoke out on our behalf when others were silent,” they told me. The famously caustic Qian, who had a photographic memory, gleefully quoted from Leys’s barbed and coruscating prose. He particularly appreciated a remark about China having a political system that “breaks eggs without ever making an omelette.”

Qian and Yang knew the costs of that system well. … He and Yang both applauded the searing indignation that coursed through Leys’s writing and his efforts to avenge “innocent victims.” The admiration was mutual… Leys called Yang Jiang “one of those subtle artists who know how to say less in order to express more.”

In 1984, Pierre asked me to bring Qian and Yang a copy of an essay he had just published called “Orwell: The Horror of Politics,” in which he noted the extent to which Orwell was “being secretly read” in China and under other totalitarian regimes (something confirmed by Dong Leshan, the Chinese translator of Orwell). A few days later, Zhongshu asked me to convey his admiration to Pierre. On a sheet of handmade Xuan paper, in his distinctive calligraphic hand, Qian congratulated Pierre that he had not “overturned the verdict”—fan’an [翻案], a classical expression made even more resonant following the Cultural Revolution—on Orwell but rather “made the case” (ding’an [定案]) for a new understanding of him. In particular, he appreciated Pierre’s observation about the “human dimension” of Orwell: “What ensures his superior originality as a political writer is the fact that he hated politics.” Leys also quoted Bernard Crick’s 1980 biography of Orwell: “He argued for the primacy of the political only to protect non-political values.”

— from Geremie R. Barmé, One Decent Man, The New York Review of Books, 28 June 2018

All of those encounters were overshadowed by the recent political drama of the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign. By early 1984, the purge of the humanist faction in the Party hierarchy and among its theoreticians and had been curtailed and its economic agenda was taking precedence once more. For sensitive writers like Dong Leshan, however, these developments did not augur well. Along with Pierre’s ‘Orwell: The Horror of Politics’, I gave him a copy of China Blames the West for “Cultural Pollution”, my journalistic analysis of the ‘mini-purge’ that had been published a few months earlier.

In ‘The Horror of Politics’ Pierre observed that ‘”The smelly little orthodoxies that compete for our souls” always have one thing in common: they deny the human dimension.’ This, too, was at the heart of the 1983 Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign, a political movement that continued the assault on human value, individual worth and humanity that had been the core of the Stalin-Maoist enterprise from the 1930s.

[Note: For more on the 1983 purge and its long-term significance, see The View from Maple Bridge 楓橋, Part I: Ah, Humanity!, 5 February 2023; Part III: An Old Tale Retold, 29 June 2023, Chapter Twenty-four of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium.]

***

The year 1984 is significant for me in a number of ways. Apart from the encounters described above, it was both the tenth year since I went to China to study, encouraged to do so by Pierre Ryckmans, as well as being my thirtieth year (I was born on 4 May 1954). Having returned to Australia in 1983, again encouraged to do so by Pierre, I was undertaking a PhD program supervised by him at my alma mater, The Australian National University in Canberra.

Forty years later, now that I am in my seventieth year, I look back at that time both with longing and gratitude, still surprised by the good fortune I had to learn about China guided by mentors, writers and translators like Pierre Ryckmans, Dong Leshan, Yang Xianyi, Gladys Yang, Qian Zhongshu and Yang Jiang.

This year also marks a decade since Pierre Ryckmans passed away on 11 August 2014. China Heritage is publishing ‘Orwell: The Horror of Politics’ both to celebrate his memory and to mark that moment forty years ago when the Communist Party revealed the limits of its reformist aspirations. I also recommend Phillip Adams, A Conversation with Pierre Ryckmans, (Late Night Live, 19 January 2012).

[Note: Phillip Adams hosted Late Night Live from 1991, his role taken up in June 2024 by David Marr, a writer and journalist who was the editor of The National Times in 1984 when that paper published my essay China Blames the West for “Cultural Pollution”.]

***

In Memory of Yvonne Preston

While celebrating the memory of Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) we also commemorate Yvonne Preston, journalist, writer and friend, who passed away in Sydney, Australia, on 17 June 2024.

Yvonne was the Beijing correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald from 1975 and she reported from and about China for the next three decades during which time she played a major role in helping Australians understand the momentous events, and their significance, unfolding in that country.

During my time in Maoist Beijing, and thereafter, Yvonne was a frequent host, a constant friend and an unfailingly insightful, and wisely skeptical, interlocutor. In 1975-1977 I saw a lot of Yvonne, and the kids. And since students like me had to bike to town (a trip of many kilometers), I was always taking showers and naps at their apartment in the foreigners compound. Her daughter Louise remembers that “Once, Mum was in Tiananmen Square and tried to take a photo of a soldier, who promptly confiscated the film, which upset us children because, as I recall, the film included a photo of [leading Australian China expert] Geremie Barme sleeping on our couch.”

Those years were even more of a battle for foreign correspondents in Beijing than now. “For a start, there was no phone book,” Yvonne recalled. “We had a single number we could ring outside the diplomatic compound for the ill-named Information Department of the Foreign Ministry. Our requests for help, answers, permission to travel, facts, news, confirmations were almost invariably met with a blank, ‘I will take note of your question’, ‘I think you know the answer to that question’. On one occasion, my ABC colleague was told, ‘We have no comment and you may not say that we have no comment’.”

‘Orwellian’ was part of our shared lexicon.

Twenty-five years later, when making Morning Sun, a history documentary about the Cultural Revolution, in Boston I convinced my fellow directors that we should frame the film around The East is Red. Yvonne is, quite literally, part of my own history.

In the following essay, Simon Leys praises the ‘unique authority’ of George Orwell, for

unlike licensed specialists and academic pundits, he could see the obvious; unlike shrewd politicians and trendy intellectuals, he was not afraid to spell it out; and unlike most political scientists and sociologists, he could do this in plain English.

I found echoes of this spirit in Yvonne’s character and in her work. They are as valuable, and as necessary, today as ever.

***

Four decades after the eponymous year of 1984, the visions both of George Orwell and of Aldous Huxley remain darkly relevant. An omnipresent Big Brother rules over societies addicted to dopamine — the modern-day soma — and which are engaged in a frenzy of boundless consumerism.

***

My thanks to Annie Ren 任路漫, Reader #1 and Richard Rigby.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 June 2024

***

Orwell has been smothered with cloying approbation by those who would have despised or ignored him when he was alive, and pelted with smug afterthoughts by those who (often unwittingly or reluctantly) shared the same trenches as he did. The present climate threatens to stifle him in one way or the other.

— Christopher Hitchens, Grand Street, winter 1984

***

Selected works by George Orwell

- Homage to Catalonia, 1938

- Animal Farm, 1944

- Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1950

- Politics and the English Language, April 1946

- The Collected Non-Fiction: Essays, Articles, Diaries and Letters, 1903-1950, Penguin, 2017

On Pierre Ryckmans

- Ian Buruma, The Man Who Got It Right, New York Review of Books, 15 August 2013

- A Year without Pierre, The China Story Journal, 11 August 2015

- An Educated Man is Not a Pot — On the University, China Heritage, March 2017

- In Memoriam — Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), China Heritage, 11 August 2021

Other Related Material

- 白杰明 (Geremie Barmé),大陸出版奧威爾的《一九八四》,《九十年代月刊》,1986年

- Pierre Ryckmans, View from the Bridge: Aspects of Culture, 1996

- Simon Leys, Misfit by Conviction, 2002, Los Angeles Times, 29 September 2002

- 馮翔, 董樂山在「1984」, 南風窗,2009年11月6日

- Phillip Adams, A Conversation with Pierre Ryckmans, Late Night Live, 19 January 2012

- ‘You are garlic chives!’ — Trisolarans, Burn Book and China’s Men in Black, 20 April 2024

- Captive Minds & Academic Angst on May Fourth 2024, 8 May 2024

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage (August 2018)-

***

Nineteen Eighty-four in 1984

The novel inspired television shows, films, plays, a David Bowie album (though Orwell’s widow, Sonia, turned down the artist’s offer to create a 1984 musical) and even a “Victory gin” based on the grim spirits described in the novel. It was cited in songs by John Lennon and Stevie Wonder and named by assassin Lee Harvey Oswald as one of his favorite books. And its imagery continues to inform the public’s perception of what might happen if 1984 weren’t fiction after all.

In January 1984, an Apple Macintosh ad directed by Ridley Scott aired during the Super Bowl. It depicted a maverick woman smashing a Big Brother-esque screen that was broadcasting to the subordinate masses, and it ended with the tagline, “You’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’” The implication was that buying Apple products would set people apart from the crowd. In an Orwellian twist, although the ad positioned Apple as the underdog against the dominant IBM, the company actually had a competitive market share, claiming 25 percent to IBM’s 24 percent at the end of 1983.

— Anne Wallentine, What Does George Orwell’s ‘1984’ Mean in 2024?,Smithsonian Magazine, 6 June 2024

***

Orwell: The Horror of Politics

Simon Leys

“There is no greater mystery than simplicity of the soul.”

— Abbe Bremond

It is hard to believe that Orwell has been dead for thirty years already. He still speaks to us with more vigour and clarity than most of the commentators and politicians whose prose can be read in today’s newspapers. Yet, it seems that many people still misunderstand him; this misunderstanding probably developed for political reasons not unlike those which, during the ‘fifties for instance, enabled Sartre and Beauvoir to excommunicate from the leftist intelligentsia, Camus and Koestler, who had been found guilty of a similar clear-sightedness.

Many readers approach Orwell from the same angle as the editors of Reader’s Digest: among all his works, they only retain Nineteen Eighty-Four, taking it out of context and arbitrarily reducing it to the dimensions of an anti-communist pamphlet. They conveniently ignore that the driving force which inspired Orwell’s antitotalitarian fight was his socialist commitment, and that, for him, socialism was not an abstract concept but a living cause which mobilised all his energies, and for which he nearly got killed during the Spanish war.

Orwell himself accurately observed:

When I feel that people like us understand the situation better than the so-called experts, it is not in any power to foretell specific events, but in the power to grasp what kind of world we are living in.

Indeed, it was this perception that vested him with a unique authority: unlike licensed specialists and academic pundits, he could see the obvious; unlike shrewd politicians and trendy intellectuals, he was not afraid to spell it out; and unlike most political scientists and sociologists, he could do this in plain English.

This rare ability equipped him with a certitude that was devoid of arrogance, even though, at times, it could prove ruthless and bruising. He was occasionally aware of his own “intellectual brutality”, but he considered its exercise to be a duty rather than a sin. He could indulge it in a way that was equally free from dogmatism and from self-righteousness, as the certitude which possessed him was not the product of an arbitrary simplification — it reflected a genuine simplicity, the very simplicity of the child who sees that the Emperor is naked (The Emperor’s New Clothes was a favourite story of his, and he even toyed with the idea of making a modern adaptation of Andersen’s tale). This aspect of his personality struck in his time a number of perceptive critics; thus, for instance, in a brilliant sketch, V.S. Pritchett concluded that he had “the innocence of a savage”.*

* The theme of ‘simplicity’ is a leit-motiv that runs through the testimonies of all those who knew him. Paul Potts: “There was something very innocent and terribly simple about him. He wasn’t a very good judge of character.” Julian Symon: “One of the most attractive features of his personality was a childlike simplicity.” Richard Rees: “Orwell had an essentially simple mind and was only able to see one point at a time.”

Simplicity and innocence are qualities that may come naturally enough to children and to savages; no civilised adult can reach them without first undergoing a rather severe discipline. In Orwell, these virtues were the crowning of a massive integrity that did not suffer the slightest gap between word and deed. He was true and clean; the writer and the man were one — and in this respect, he was the exact opposite of an homme de lettres. Here, by the way, may lie an explanation for his paradoxical, yet solid friendship with Henry Miller: apparently nothing could have been more unlikely than this close association between the gloomy prophet of totalitarian doom and the ribald prophet of liberated sex; actually, they recognised each other’s genuineness: both could back with their lives every word they wrote.

It is precisely for this reason that our wish to know the details of Orwell’s biography (a wish now fulfilled by Bernard Crick’s admirable and definitive study*) did not correspond to some idle curiosity. His life may not have been as important as his writings; yet, it vouchsafed for them.

* B. Crick, George Orwell: A Life, Secker & Warburg, London 1980.

The sympathetic admiration which Crick feels for his subject is never blind. His assessment of Orwell as “a man of near-genius” is fair, and typical of his sober approach. Neither does he try to gloss over less attractive aspects of Orwell’s personality; he went unhesitatingly to open his darkest and most secret closets. At the end of this very thorough exploration, what strikes the reader is that this man who protected so jealously his privacy, had after all nothing to hide. “Saintliness” is a word which earlier biographers and witnesses were often tempted to use on his subject; of course, for a scholar as conscientious and objective as Crick, such a notion appears rather distasteful. Orwell himself had a healthy distrust for saints, as he showed so well in his essay on Gandhi:

The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes it makes friendly intercourse impossible and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one’s love upon other human individuals.

Here, the striking paradox, of course, is that the fierce and extreme demands which he constantly imposed upon himself, were precisely akin to perfection-seeking; he actually “pushed asceticism” to a point which sometimes bordered on self-torture, and if not making “friendly intercourse impossible”, at least hastened his own death; life, in the end, could neither defeat nor break him, whereas one could perhaps not say the same concerning the brave woman who had accepted “to fasten her love” upon him, and who literally died of cancer under his very eyes without his noticing it, as he was kept busy by his concern for the ills and sufferings of mankind. Richard Rees who knew him intimately and had a deep affection for him, concluded:

If the raw material of heroism consists partly of a sort of refined and sublimated egoism, it is to be expected that progress through life of a man of superior character will leave behind it a more disturbing backwash than the sluggish progress of the average man.

For his close entourage, an innocent of Orwell’s calibre is obviously more to be feared than a cynic.

***

“When a writer chooses another name for his writing self, he is doing more than inventing a pseudonym: he is naming, and in a sense, creating, his imaginative identity.” This observation by Samuel Hynes (on Rebecca West) seems particularly fitting in Orwell’s case. The process by which Eric Blair became George Orwell was subtle and gradual; perhaps it was never fully completed, nor could it be, by very definition. Crick describes it well:

The Orwell part of himself was for Blair an ideal image to be lived up to: an image of integrity, honesty, simplicity, egalitarian conviction, plain living, plain writing and plain speaking, in all, a man with an almost reckless commitment to speaking unwelcome truths.

In his last will, Orwell expressed the wish that no biography be written of him. This interdiction did not simply reflect the belief which he had previously expressed: “every life viewed from the inside would be a series of defeats too humiliating and disgraceful to contemplate” — , more deeply perhaps, there was this fact that ‘George Orwell’ embodied for him an ethical and asthetical imperative by whose standards Eric Blair was necessarily to be found wanting. Thus, between the ideal abstraction of the public figure and the irrelevance of the private man, there was no ground on which a biographer could build.

In the full maturity of his talent, Orwell defined himself as “a political writer — with equal emphasis on the two words”. Yet, the odd thing is that, both in politics and in literature, he found his true way very late and after many detours. From the earliest age, he never doubted his literary vocation, but his first earnest creative attempts, in his late twenties, were dismal failures: not only did he write badly, but he did not even know what to write about. (These early manuscripts were all lost or destroyed.) It is only after years of obstinate and seemingly hopeless efforts that he finally began to develop his own voice and his own vision with Down and Out in Paris and London — even though he did not fully succeed in sustaining these consistently all through the book. Henry Miller thought that it was his best work; this judgment is very debatable, but there is no doubt that, for all its unevenness, Down and Out is of capital importance. It is in this book that Orwell discovered a new form which he was eventually to bring to perfection (in two books, the Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia, as well as in several short essays such as Shooting an Elephant and A Hanging) and which remains, from a purely literary point of view, his most original achievement: the transmutation of journalism into an art, the recreation of reality under the guise of factual, minutely precise and objective reporting (a quarter of a century later, Norman Mailer and Truman Capote wasted much time challenging each other’s claim to be the true inventor of the “non-fictional novel”: they forgot that Orwell had explored this area long before them).

The strange thing is that, instead of immediately developing and consolidating his successful new technique, Orwell veered away from it and reverted for a while towards traditional fiction. His four exercises in this more conventional art (Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, Coming up for Air) are not uninteresting; however, if we still read them, it is partly for the additional light which they can throw on Orwell’s mind and personality; had they been signed with another name, it is doubtful whether they would still be reprinted today.

If Orwell took a painstakingly long time to find his literary identity, he was even slower in discovering his political vocation. Actually, when we consider the very subject of his first book — a dive into the sub-proletarian depths to explore the condition of casual workers, tramps and beggars — Down and Out appears amazingly non-political. The same observation could be made of his early novels: for instance, Burmese Days is set in a colonial society and yet, it could not be described as a “political” novel any more than, let us say, A Passage to India (the equal severity with which Orwell treats both the British and the Burmese sides could directly paraphrase E.M. Forster’s conclusion: “Most Indians, like most English people, are shits”): politics figure in it merely as a natural component of the reality that is being observed.

Orwell’s conversion to socialism took place relatively late in his career, as he was already the author of four books which had achieved if not popular success, at least critical recognition. Rather by accident, in 1936, a left-wing publisher commissioned him to write at short notice a kind of inquiry on the workers’ conditions in the industrial north of England during the Depression. His journey lasted a few weeks only; yet this direct encounter with social injustice and human misery was for him a shattering revelation. His socialist “illumination” was as sudden and absolute as the satori experienced by a Zen adept, or one could say that The Road to Wigan Pier was his Way to Damascus. These metaphors may appear inappropriate when we consider his innate allergy to all norms of religion (and more particularly he felt an even stronger revulsion for a certain form of socialist mystique that used “to draw with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature-cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England”); and yet, it seems that only a reference to a religious experience could adequately account for the instantaneous, total and unshakeable character of his new commitment. To pursue with the Zen image which has just been suggested, it should be added that, although his conversion had a radical impact upon his whole life and personality, he always dispensed happily with all Scriptures and liturgies: sometimes even, to the dismay of his more conventional brethren, he showed that he was one of those inspired and iconoclastic monks who, on a cold winter night, would not hesitate to take an axe and chop a few holy statues into firewood.

In the Wigan Pier experience, he did not remain a mere spectator. His powers of empathy enabled him to live from inside what Simone Weil had called with a terrible simplicity “le malheur“, when she attempted to describe the radical devastation, the crushing of the soul which factory work inflicted upon her. By the way, this is not the only instance where Orwell reminds us of Simone Weil; as several critics have already pointed out, some striking comparisons could be established between these two figures: not only their development followed similar stages: decisive discovery of the condition of the working class, involvement with the Socialist movement, participation in the Spanish war, but most of all, they both burned with the same passion for justice, they both cultivated poverty and asceticism to a degree which bordered on self-punishment. (Yet, by contrast, these similarities strikingly underline their one essential divergence: “waiting for God” opens Weil’s writings into the infinite; the absence of God makes Orwell’s world oddly flat — devoid of mystery; it is somehow stunted, lacking vibrations and echoes; he aims at perfect clarity but excludes poetry in his attempt to reduce all things merely to what they are.)

One passage in Wigan Pier can summarise the lightning revelation that struck Orwell when, on his journey through the bleak land of the unemployed, he suddenly stared human misery in the face. A fleeting vision barely glimpsed for a few seconds from a train, acquires through his narrative, permanent and irrefutable truth:

The train bore me away, through the monstrous scenery of slag-heaps, chimneys, piled scrap-iron, foul canals, paths of cindery mud criss-crossed by the print of clogs. This was March, but the weather had been horribly cold and everywhere there were mounds of blackened snow. As we moved slowly through the outskirts of the town, we passed row after row of little grey slum-houses running at right angles to the embankment. At the back of one of the houses a young woman was kneeling on the stones, poking a stick up the leaden waste-pipe which ran from the sink inside and which I suppose was blocked. I had time to see everything about her — her sacking apron, her clumsy clogs, her arms reddened by the cold. She looked up as the train passed and I was almost near enough to catch her eye. She had a round, pale face, the usual exhausted face of the slum girl who is twenty-five and looks forty, thanks to miscarriages and drudgery; and it wore, for the second in which I saw it, the most desolate, hopeless expression I have ever seen. It struck me then that we are mistaken when we say that “It isn’t the same for them as it would be for us” and that people bred in the slums can imagine nothing but the slums. For what I saw in her face was not the ignorant suffering of an animal. She knew well enough what was happening to her — understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold, on the slimy stones of a slum backyard, poking a stick up a foul drainpipe.

We see Orwell developing here a style and a method that were to achieve classic perfection shortly afterwards in Shooting an Elephant. Crick has compared the final version of Wigan Pier with the notebooks which Orwell kept during his journey, and his analysis is fascinating; he shows that Orwell, far from reproducing the direct observations and raw impressions which he first recorded on the spot, carefully reconstructed, modified and reorganised his actual experiences — in other words, “the plain descriptive style of the documentary is indeed a very deliberate artistic creation“. This point is essential, and suggests far-reaching implications. What Orwell’s invisible, yet supremely efficient art illustrates is that, in writing, there can be no such thing as “factual truth”. Facts by themselves only offer a senseless chaos; artistic creation alone can endow them with meaning, by investing them with form and rhythm. Imagination does not merely perform an aesthetic function — its role is also ethic. Literally, truth must be invented.

This principle, first applied on the modest scale of a social inquiry in an industrial region of England, was progressively to reveal its vaster potential: eventually it came to inspire the prophetic vision of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Orwell who greatly admired D.H. Lawrence, once defined the latter’s creative genius as “the extraordinary power of knowing imaginatively something that he could not have known by observation”. In his humility, he considered that he himself was lacking such a talent: however, this was true only within the traditional area of the psychological novel. There indeed, when he had to invent characters, his creative imagination proved rather thin and limited. But his “sociological imagination” was eventually to enable him to extrapolate from tenuous fragments of experience, the massive, complete, coherent and truthful reality of the totalitarian abyss on the edge of which we are now so precariously tottering.

In this respect, Orwell’s literary method contains a lesson whose implications have broad political and moral relevance. Recent history has repeatedly shown how easily entire nations could suddenly find themselves plunged into the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four: all it needs is a mere handful of determined and well-organised scoundrels who simply derive their strength from the silence and blindness of the broad majority of decent people. Decent people say nothing because they see nothing. And they see nothing, not because they have no eyes; but because they have no imagination.

***

***

The experiences of childhood and youth may not strictly determine a man’s future; at least they sharpen — or blunt — certain facets of his sensitivity; they make him particularly receptive, or vulnerable, to certain encounters in later life; they lay the ground on which some seeds will more easily take root.

The six years which Orwell spent in boarding school, from age 8 till 13, were emotionally traumatic and played a decisive role in the moulding of his personality. The feeling of utter dereliction, the sense of inadequacy and failure (bordering sometimes on self-pity), the weight of unaccountable guilt that crushed him as a child, were never really to leave him in his mature years. On the one hand, these feelings instilled in him a kind of relentless, quasi-masochistic urge for self-punishment; on the other hand, they inspired his instinctive and permanent rebellion against all established authorities and they enabled him to empathise spontaneously with the weak and the downtrodden.

Crick attempts, somewhat unconvincingly (it is the only point on which I would venture to criticise his otherwise admirable book), to downplay the significance of these early experiences. He goes to great lengths to challenge the factual accuracy of Such, Such were the Joys — the posthumously published essay in which Orwell describes the nightmare of his schoolboy years. To me, it seems irrelevant — if not self-defeating — to question the veracity of this autobiographical account, on the grounds of its much later date. Actually, the very fact that these memories should have remained so vivid after an interval of more than thirty years testifies precisely for the genuine intensity of the pain and anger which suffuse them. It would be perfectly idle to investigate now whether this essay presents fictional elements, or to determine the exact amount of literary transposition that it may contain. With the sole exception of Homage to Catalonia, where he had to observe meticulous factual accuracy in order to ward off potential counter-attacks from Stalinist quarters, all of Orwell’s journalistic reports and narratives constitute an imaginative reinterpretation of reality. As we have just seen — and Crick himself underlined it — Orwell always subtly rearranges his facts, he modifies them with conscious and deliberate art, in order to reveal their inner truth. A Hanging and Shooting an Elephant have long been considered as models of objective, accurate reporting; yet, as we have now reached a subtler appreciation of his literary method, we are not so sure any more that he ever witnessed a hanging, or shot an elephant; at the same time, we also realise how little it matters to answer these questions, since the real import of these essays is obviously not dependent upon their factual accuracy. Why should we now adopt another attitude when looking at Such, Such were the Joys? Besides, the main question is not to determine whether his old school was actually as awful as he described it, but if his description truly reflects the impression it had left on him as a child. On this particular point, the long-lasting violence and bitterness of his resentment leave no room for doubt. After his old schoolmate Cyril Connolly published a book of reminiscences in which their school was painted in much milder colours, Orwell — then a man of thirty-five — reacted at once with characteristic vehemence: “I wonder how you can write about St. Cyprian’s. It’s all like an awful nightmare to me … People are wrecked by those filthy private schools.”

It may well be that he exaggerated certain aspects of his schoolboy’s misery, but these exaggerations themselves are meaningful — as Chesterton said: “It is right to exaggerate when one exaggerates the right thing.” I do not see why we should follow Crick in downplaying the view often expressed by Orwell’s friends, that the bullying and wretchedness of his early years at school prepared him to reject with indignation colonial injustice which he was to witness in Burma, and more generally to take forever afterwards the side of the underdog with passionate empathy. Furthermore, a parallel reading of Such, Such were the Joys and Nineteen Eighty-Four clearly reveals that, just as Chinese landscape painters create a big mountain from the observation of a small pebble, Orwell probably found in his old prep school a first microcosmic embryo of his huge cacopian [cacoptopian? — ed.] vision. On this particular point, I see no reason to doubt Tosco Fyvel’s testimony: “Orwell told me … that the sufferings of a misfit boy in a boarding school were probably the only English parallel to the isolation felt by an outsider in a totalitarian society.”

On a more concrete level, Fyvel also observes how various aspects of school life were to supply some of the sounds, sights and smells of Nineteen Eighty-Four. “… early in life, Orwell showed his quite unusual sensitivity towards ugly or hostile environments. This emerges in his description of the repellent sides of life at St Cyprian’s. As he recalls his impressions of the sour porridge constantly served up on unclean plates, the slimy water in the plunge baths, the hard, lumpy beds, the sweaty smell of the changing room, the lack of all privacy, the rows of filthy lavatories without locks, and he constant noise of the banging lavatory doors and the echoing sound of chamber pots in the dormitories — as he recalls this with that peculiar sensitivity of his, one can almost see Orwell using his description of St. Cyprian’s as a trial run for the shabbiness of Nineteen Eighty-Four”.

The natural wretchedness of boarding school life was further compounded for him by an additional distress: his family belonged to the upper layer of the middle-class, but did not have the financial resources needed to maintain its status. The Principal of the school made him suffer acute humiliation by revealing to him that he had been admitted out of charity. Long afterwards, he wrote on this subject:

Probably the greatest cruelty one can inflict on a child is to send it to a school among children richer than itself. A child conscious of poverty will suffer snobbish agonies such as a grown up person can scarcely imagine.

Even in Eton, where he finally found himself in a more congenial atmosphere, he still had to bear with the humiliation of being there on a scholarship among a majority of wealthy or aristocratic schoolmates. Some twenty-five years later, exchanging old school memories with him, Richard Rees was stunned to discover that this adolescent wound was still raw and bleeding in the adult Orwell.

Class-stratifications with their all-pervasive, invisible yet impassable barriers, poison English society to a degree that is not found anywhere else in Europe. Because of the trauma of his school years, Orwell developed an intense sensitivity to this evil; he came to feel visceral hatred and revulsion for the upper-class to which he belonged by birth and education, but in which he had been prevented by narrow family circumstances from occupying his natural place. On this subject, his anger never relented. In hospital, during his final illness, shortly before his death, he once heard aristocratic voices of visitors in the next room, and was immediately moved to jot down with furious energy in his note-book:

… What voices! A sort of over-fedness, a fatuous self-confidence, a constant bah-bahing of laughter about nothing, above all a sort of heaviness and richness combined with fundamental ill-will — people who, one instinctively feels, without even being able to see them, are the enemies of anything intelligent or sensitive or beautiful. No wonder everyone hates us so.

This accursed class-consciousness (he was cruelly aware that, for all his efforts, he still belonged to the odious upper-class, as it is denoted by his use of the pronoun “us” in the passage we just quoted) always interposed itself between him and the others. There was no hope for the old Etonian of ever becoming able to merge inconspicuously into a proletarian crowd. The warm reality of working-class brotherhood was inexorably denied to him. And yet, God knows how hard he tried, going through this rigmarole of “formalised cockney”, this painstaking charade of disguising himself as a tramp or a beggar. He repeatedly effected gruelling and dangerous dives into the lower depths of society, sharing the condition of outcasts, hoboes and other human wrecks. Although these expeditions yielded a remarkable literary harvest, they do not seem to have ever significantly helped him to overcome his native incapacity to establish a simple and natural communication with people belonging to a lower social standing — let alone to divest himself of his upper-class accent (he himself observed: “Englishmen are branded on the tongue.”) His sense of humour enabled him to confess the ludicrous, yet revealing, episode of his vain attempt to spend one Christmas in gaol. Masquerading once more as a vagrant, he methodically emptied a bottle of whisky, then went to abuse a policeman in the hope of getting himself arrested. The policeman, however, detected at once the true Etonian gentleman under those borrowed rags; he did not take the bait and paternally advised him to go home …

In the end, it is perhaps his niece who summarised the problem most neatly (in an interview which she granted Crick): “A lot of his hang-ups came from the fact that he thought he ought to love all his fellow men, and he could not even talk to them easily.”

After Eton, why did Eric Blair choose, of all possible careers, that of a colonial police officer in Burma? The experience was to prove instructive as it enabled him to witness at close range the dirty work which is entailed by the everyday running of a colonial empire — but this, of course, is hindsight wisdom, of which he could have had no inkling when he first volunteered; many more years would have to pass before he became a staunch opponent of British imperial policies.

Actually, the question we just asked is a false one. The idea that George Orwell could ever have volunteered for an outfit specifically geared to enforce colonial oppression would seem ludicrous, to say the least. However, there was nothing strange with a 19-year-old Eric Blair making such a move: having just graduated from a school that traditionally supplied the Empire with its best civil servants and soldiers, he could not go to Oxford or Cambridge for further studies: his family could not afford the fees and his final results at Eton had been too mediocre to warrant a scholarship. A colonial career appeared all the more suitable for him, as his family already had a strong Anglo-Indian background: his father had spent a lifetime in the Indian administration and his maternal grandparents had settled in Burma. Moreover, like many young men who had to sit out the First World War as they were still attending high school, and who had been fed with countless stories of the heroic deeds performed by their elders on the battlefields, there was in him a long-frustrated longing for adventure and action, an adolescent fascination with uniforms, guns and exotic horizons. Why indeed not join the Imperial Police in Burma?

The Burmese experience lasted five years, and was another decisive stage in his formation. It increased his guilt-feelings and may have contributed to foster in him a certain masochistic streak (which does recall, in a much milder form, the case of T.E. Lawrence). Finally, when he decided to leave the Imperial Police, he lucidly described his state of mind: “I was conscious of an immense weight of guilt that I had to expiate … I felt that I had to escape not merely from imperialism, but from every form of man’s dominion over man. I wanted to submerge myself, to get right down among the oppressed; to be one of them, and on their side against their tyrants… At that time failure seemed to me to be the only virtue. Every suspicion of self-advancement, even to succeed in life, to the extent of making a few hundred a year, seemed to me spiritually ugly, a species of bullying.”

His systematic experiments among the down-and-outers, as well as his determination always to side with the victims*, eventually led him to conduct his momentous inquiry among unemployed workers — which, in turn, triggered his conversion to socialism. As we can see, the chain-reaction that was to culminate in the most decisive commitment of his life, had thus originated in a wish to atone for his earlier colonial sins. Similarly, his deep and strong anarchist leanings (before calling himself a Socialist, he first defined himself as a “Tory anarchist” which is probably the most accurate description of his political temper) were also for him a radical way of rejecting his past association with Law-and-Order in one of its ugliest forms.

* “I had begun to have an indescribable loathing of the whole machinery of so-called justice. Say what you will, our criminal law is a horrible thing. It needs very insensitive people to administer it (…) I watched a man hanged once; it seemed to me worse than a thousand murders. I never went into a jail without feeling that my place was on the other side of the bars. I thought then — and I think now, for that matter — that the worst criminal who ever walked is morally superior to a hanging judge.” (The Road to Wigan Pier.)

Yet, the legacy of his Burmese period was far from being merely negative. First, it provided inspiration and material for a number of his works: it supplied the subject-matter and background of what can be considered the best of his four “conventional” novels, Burmese Days, as well as an important part of his journal-ism; more especially, his two most celebrated narrative essays were also directly based upon his colonial memories.

Even though he eventually became a fierce critic of the British imperial system and a forceful advocate of total decolonisation, he never disavowed his Burmese years.

He was able to integrate into his own complex world-view, the particular insights which he had derived from his colonial experience. For instance, he achieved an understanding of the actual realities of imperialism far more profound than that of his fellow-socialists, and on this subject, his nuanced perception stood in sharp contrast to the comfortable and conventional simplifications usually indulged by the Left. He had little patience with the sham of a certain type of fashionable anti-colonialism, and exposed its essential hypocrisy in one of his essays on Kipling (for whom he felt a revealing and ambivalent fascination):

… because Kipling identifies himself with the official class, he does possess one thing which “enlightened” people seldom or never possess, and that is a sense of responsibility. The middle-class Left hate him for this, quite as much as for his cruelty and vulgarity. All Left-wing parties in the highly industrialised countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life with which these aims are incompatible. We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are “enlightened” all maintain that those coolie ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our, and hence our “enlightenment” demands that the robbery shall continue. A humanitarian is always a hypocrite, and Kipling’s understanding of this is perhaps the central secret of his power to create telling phrases. It would be difficult to hit off the one-eyed pacifism of the English in fewer words than in the phrase “making mock of uniforms that guard you while you sleep”. It is true that Kipling does not understand the economic aspect of the relationship between the highbrow and the Blimp. He does not see that the map is painted red chiefly in order that the coolie may be exploited. Instead of the coolie, he sees the Indian civil servant, but even on that plane, his grasp of function, of who protects whom, is very sound. He sees clearly that men can only be highly civilised, while other men, inevitably less civilised, are there to guard and feed them.

Orwell himself briefly outlined his evolution after Burma:

I underwent poverty and a sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism; but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation… The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly against totalitarianism, and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.

Although this outline fails to mention the Wigan Pier experience, it is otherwise an accurate description of his development, in which the Spanish war came indeed to mark a crucial turn.

The conscious motivations that made him volunteer or the defence of the Spanish republic were simple, sincere, strong and sound. “I am going to Spain”, he announced to one of his editors. “Why?”, the other asked. “This fascism”, he said, “somebody’s got to stop it.”

***

***

Yet, other factors may have unconsciously compounded his decision. To mention these should not detract in the slightest from the nobility, the generosity and the courage of his commitment; still, it could contribute to throw some more light on one aspect of his psychology. Paradoxically, the impulse that determined Orwell to fight fascism in Spain, was perhaps not totally unlike the one which, earlier on, had inspired the young and politically ignorant Eric Blair to enlist in the Burmese colonial police. On this subject, it may be relevant to quote here a very significant confession which he once made to Richard Rees (oddly enough, Crick seems to have completely ignored it):

Orwell did once make a remark to me which seems to give a clue to the obscurer part of his character. Speaking of the First World War he said that his generation must be marked forever by the humiliation of not having taken part in it. He had of course been too young to take part. But the fact that several million men, some of them not much older than himself had been through an ordeal which he had not shared was apparently intolerable to him.

Besides, there is no doubt that Orwell was always fascinated with physical courage, guns, mateship, action (genuine values can be found there, which it would be foolish for intellectuals to deny). Actually he had developed a real competence in military affairs. Thus, in Spain, his experience as a former police officer was immediately put to good use in the training of young volunteers; later on, during the Second World War, he took the initiative to draft a highly professional project for the organisation of people’s militias to be used in case of German invasion (this original suggestion was submitted to the Ministry of Defence, but never drew any reply). Elsewhere, Crick pointedly remarked: “Orwell, like Churchill, was more of a Roman republican than a modern liberal: the hardships and excitements of war had some positive appeal to him … he scorned the pacific and the overscrupulous.” This trait was to show even more clearly at the beginning of the war, and inspired Cyril Connolly to comment:

Orwell slipped into the war as into an old tweed jacket … He felt enormously at home in the Blitz, among the bombs, the bravery, the rubble, the shortages, the homeless, the signs of rising revolutionary temper.

Eunuchs who preach chastity are never very convincing. Conversely, what gave Orwell’s crusades such a persuasive power was the feeling that he himself had actually experienced and understood from within the very ills which he attacked. Contrary to what was the case with too many orthodox Leftists, he literally knew what he was talking about. Thus, for instance, in the socialist camp, he was one of the very few people who always rejected the dogmatic simplification that described fascism as a form of “advanced capitalism”. On the contrary, he clearly perceived that “fascism was a perversion of socialism, a genuine mass-movement with an elitist philosophy but a popular appeal.” Furthermore, on a psychological level, he could even venture to state that “the people who have shown the best understanding of fascism are either those who have suffered under it, or those who have a fascist streak in themselves.” It should perhaps not be too difficult to find such a streak in Orwell himself; however, such a psychological analysis would not be very useful and could be misleading: what I wished to underline here is merely the admirable capacity which Orwell had to discover in himself, and to know from inside, the evils which he exposed and resisted. C.G. Jung observed that, in order to effect a cure, a good doctor ought, to some extent, to share his patient’s illness. “Only the wounded physician heals.” Orwell seems to have intuitively reached a similar conclusion — witness for instance his critical assessment of H.G. Wells’ limitations: “he is too sane to understand the modern world”. Conversely, if the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four succeeds in evoking such an unremitting terror, it is because we realise that the horror is not exterior to us: it echoes a horror which Orwell first identified in himself.

It is this human dimension that sets Orwell’s works apart in the political literature of our time. More specifically, what ensures his superior originality as a political writer, is the fact that he hated politics. Even people who were fairly close to him seem to have overlooked this paradox; thus for instance, Cyril Connolly who was his colleague in journalism (and had been his old schoolmate) could say: “Orwell was a political animal. He reduced everything to politics (…) He could not blow his nose without moralising on the conditions in the handkerchief industry.” Yet, on the other hand, his second wife whose understanding and knowledge of the private Orwell could hardly be doubted, would have us believe that his political commitment had been a historical accident; according to her, his true nature made him aspire to live in quiet retirement in the countryside, with the occasional company of one or two old friends for all society; had he been allowed to follow his own inclinations, he would only have written novels and looked after his vegetable garden. In a sense, both witnesses were right — each one simply missed the other half of the picture. Crick has an excellent formula that could actually reconcile both views: “He argued for the primacy of the political only to protect non-political values.” When he applied himself to growing turnips, to feeding his goat and to building clumsy furniture, he was not merely indulging some hobbies: he was illustrating a principle; similarly, when writing his regular column for a leftist journal, he would sometimes deliberately waste the precious space that should have been entirely devoted to the grave issues of the class-struggle, with a description of the life and habits of the common toad: the purpose of such deliberate provocations was to remind his readers that, in the proper order of priorities, the frivolous and the eternal should come before politics.

Politics should mobilise all our attention — like a mad dog that might jump at your throat, should you turn your eyes away from it for one second. It was in Spain that he discovered how ferocious the beast could be: after a fascist bullet had grievously wounded him, he was brought back from the battlefront only to find himself hunted by Stalinist thugs whose main preoccupation was not to defend the republic against the fascist enemies, but to exterminate their own anarchist allies. Back in England, when he attempted to tell how the Communists had betrayed the Spanish republic, he was immediately — and for a long time — surrounded with a double wall of silence and slander: every survivor and witness had to be similarly gagged, so as to enable the Comintern commissars and their Leftist auxiliaries to rewrite History without being challenged. Thus, for the first time, he was directly confronted with the totalitarian lie: “History stopped in 1936.”*

* “I remember saying once to Arthur Koestler, “History stopped in 1936”, at which he nodded in immediate understanding. We were both thinking of totalitarianism in general, but more particularly of the Spanish civil war. Early in life, I had noticed that no event is ever correctly reported in a newspaper, but in Spain, for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed. I saw troops who had fought bravely denounced as cowards and traitors, and others who had never seen a shot fired hailed as the heroes of imaginary victories; and I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies, and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that had never happened. I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various “party lines”. (Looking Back on the Spanish War)

He would never forget this lesson. His long political education which had started gropingly and haphazardly twenty years before, when he first joined the Burmese police, was finally completed. Now he could conclude: “What I saw in Spain, and what I have seen since of the inner workings of left-wing political parties, have given me a horror of politics.” This was to remain his fundamental stand till death; his three masterpieces would spring from it: Homage to Catalonia, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Primacy of the individual. Ideology kills. “The smelly little orthodoxies that compete for our souls” always have one thing in common: they deny the human dimension. Once you reject abstract categories, murder ceases to be easy. A post-scriptum from the Spanish front illustrates this discovery:

We were in a ditch, but behind us were two hundred yards of flat ground with hardly enough cover for a rabbit (…) A man jumped out of the [enemy] trench and ran along the top of the parapet in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him (. ..) I did not shoot partly because of that detail about the trousers. I had come here to shoot at “Fascists”; but a man who is holding up his trousers isn’t a “Fascist” visibly a fellow-creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t feel like shooting at him.

Later on, a similar impulse will, for instance, inspire his energetic debunking of Sartre’s essay on the Jewish question:

Antisemitism is obviously a subject that needs serious study, but it seems unlikely that it will get it in the near future. The trouble is that so long as antisemitism is regarded simply as a disgraceful aberration, almost a crime, anyone literate enough to have heard the word will naturally claim to be immune from it; with the result that books on antisemitism tend to be mere exercises in casting motes out of other people’s eyes (…) Part of what is wrong with M. Sartre’s approach is indicated by his title.* “The” antisemite, he seems to imply all through the book, is always the same kind of person, recognisable at a glance and, so to speak, in action the whole time. Actually one has only to use a little observation to see that antisemitism is extremely widespread, is not confined to any one class, and, above all, in any but the worst cases, is intermittent. But these facts would not square with M. Sartre’s atomised vision of society. There is, he comes near different, categories of men, such as the worker and “the” bourgeois, all classifiable in much the same way as insects. Another of these insect-like creatures is “the” Jew, who, it seems, can usually be distinguished by his physical appearance (. . .) It will be seen that this position is itself dangerously close to antisemitism. Race prejudice of any kind is a neurosis, and it is doubtful whether argument can either increase or diminish it, but the net effect of books of this kind, if they have any effect, is probably to make antisemitism slightly more prevalent than it was before. The first step towards serious study of antisemitism is to stop regarding it as a crime. Meanwhile, the less talk there is about “the” Jew or “the” antisemite, as a species of animal different from ourselves, the better.

* Portrait of the Antisemite.

His abhorrence of all abstract classifications and ideological masks, his endeavour to discover common human features even behind the most grotesquely distorted appearances, characterise Orwell’s humanism.

For him, even in its diseased, criminal or perverse manifestations, mankind remains irreducibly one. No political demonology could ever amputate any of its members. Thus, when he was war correspondent at the end of the Second World War, he drew this characteristic portrait of a sadistic SS prisoner convicted of hideous crimes:

Quite apart from the scrubby, unfed, unshaven look that a newly captured man generally has, he was a disgusting specimen. But he did not look brutal in any way frightening: merely neurotic, and in a low way, intellectual. His pale, shifty eyes were deformed by powerful spectacles. He could have been an unfrocked clergyman, an actor ruined by drink, or a spiritualist medium. I have seen similar types in London common lodging houses, and also in the Reading Room of the British Museum. Quite obviously he was mentally unbalanced — indeed, only doubtfully sane (…) So the Nazi torturer of one’s imagination, the monstrous figure against whom one had struggled for so many years, dwindled to this pitiful wretch, whose obvious need was not for punishment, but for some kind of psychological treatment.

Yet, this type of lay humanism fails probably to grasp effectively the mystery of evil; the attempt to reduce it to various forms of neurosis is not very convincing. In the end, the only absolute standards to which Orwell’s thought can refer are the deliberately vague notions of “sanity” and “decency” — largest common denominators of a civilised society, they provide the basis for a pragmatic consensus, whose very unanimity should dispense from further definition.

For Orwell, socialism provided the final solution of a very personal problem: how to communicate with the oppressed. Guilt-ridden after his service in the colonial police, he gropingly started to search for a brotherhood that could bridge the seemingly impassable chasm which separated him from the working class. It all began with a muddled attempt simply to drop out of “the respectable world” and to join the side of the victims. But eventually, at the end of his long quest, in the Spanish war, the impossible communion which he so desperately sought, suddenly became a reality. Orwell has recorded the successive stages of his itinerary not in the language of an intellectual, but with the intuitive economy of an artist: instead of developing a discursive analysis, he summarised his evolution by describing the two key-encounters that marked the beginning and the climax of his spiritual journey.

The first of these episodes took place in England, after he had disguised himself as a tramp to attempt his first “dive” :

At the start it was not easy. It meant masquerading and I have no talent for acting. I cannot, for instance, disguise my accent, at any rate not for more than a very few minutes (…) I got hold of the right kind of clothes and dirtied them in appropriate places (…) One evening, having made ready at a friend’s house, I set out and wandered eastward till I landed up at a common lodging house in Limehouse Causeway. It was a dark, dirty-looking place (.. ) Heavens, how I had to screw up my courage before I went in! It seems ridiculous now. But you see, I was still half afraid of the working class. I wanted to get in touch with them, I even wanted to become one of them, but I still thought of them as alien and dangerous; going into the dark doorway of that common lodging house seemed to me like going down into some dreadful subterranean place — a sewer full of rats for instance. I went in fully expecting a fight. The people would spot that I was not one of themselves and immediately infer that I had come to spy on them; and then they would set upon me and throw me out — that was what I expected (…) Inside the door (…) there were stevedores and navvies and a few sailors sitting about playing draughts and drinking tea. They barely glanced at me as I entered. But this was Saturday night and a hefty young stevedore was drunk and was reeling about the room. He turned, saw me, and lurched towards me with broad red face thrust out and a dangerous-looking fishy gleam in his eyes. I stiffened myself, so the fight was coming already! The next moment the stevedore collapsed on my chest and flung his arms round my neck. ‘ ’Ave a cup of tea, chum!’ he cried tearfully. ‘ ’ave a cup of tea!’

I had a cup of tea. It was a kind of baptism.

Yet, however much he multiplied these experiments, the encounters which they provided were irremediably vitiated by artifice: “it meant masquerading”. He could wear stinking rags: that did not turn him into a genuine proletarian; poverty and hunger were a condition he freely chose: these were not his fate. His forays into the lower depths of society could be gruelling sometimes, still he retained the possibility to come up for air at any moment: all he needed was a shower and a change of clothes, and he could be back among his friends, chatting about Joyce and Eliot. He could record the flavour, the colour and the smell of destitution — he himself was not chained into it, and his freedom as an observer condemned his endeavours to remain finally a kind of play-acting — like military exercises which, however professional and earnest, are always closer to the infantile games of boy-scouts, than to the horrors of war.

It is in the Spanish war that he finally was to find the true and total communion which he had been thirsting for. Homage to Catalonia opens with this scene:

In the Lenin barracks of Barcelona, the day before I joined the militia, I saw an Italian militiaman standing in front of the officers’ table. He was a tough looking youth of twenty-five or six, with reddish-yellow hair and powerful shoulders. His peaked leather cap was pulled fiercely over one eye (…) something in his face deeply moved me. It was the face of a man who would commit murder and throw away his life for a friend – the kind of face you would expect in an Anarchist, though as likely as not he was a Communist. There were both candour and ferocity in it; also the pathetic reverence that illiterate people have for their supposed superiors (…) I hardly know why, but I have seldom seen anyone — any man, I mean — to whom I have taken such an immediate liking. While they were talking round the table some remark brought it out that I was a foreigner. The Italian raised his head and said quickly: “Italiano?” I answered in my bad Spanish: “No, Inglès. Y tú?” “Italiano.” As we went out, he stepped across the room and gripped my hand very hard. Queer, the affection you can feel for a stranger! It was as though his spirit and mine had momentarily succeeded in bridging the gulf of language and tradition and meeting in utter intimacy. I hoped he liked me as well as I liked him. But I also knew that to retain my first impression of him, I must not see him again; and needless to say I never did see him again. One was always making contacts of that kind in Spain.

Thus, he who originally “could not talk easily to his fellow-men”, now did not even need a language to communicate with his revolutionary comrades. He could find full and natural acceptance in the workers’ brotherhood without having to go through the old, painstaking proletarian play-acting; there was no more need for disguise: it was enough that he be fighting the same fight.

The meeting with the young Italian militiaman was to remain for him the symbol of such a memorable revelation, that not only did he use this episode as the opening of Homage to Catalonia, but, six years later, he twice came back to it, finding in it the inspiration of his most accomplished poem — a piece of amazing emotional intensity, especially for a writer who usually kept his private feelings so carefully in check. (Needless to say, sagacious psychoanalysts and other profound idiots immediately smelled here the subtle traces of a subconscious and hidden homosexual inclination. To determine whether Orwell did actually harbour such a tendency in his subconscious, seems to me about as important as to find out whether he had flat feet.* Our age tries very hard to decipher symbols of sex everywhere — will it ever understand that sex is sometimes the symbol of something else?)

* Is it really necessary to add that Orwell did indeed love women very much — not only the two whom he successively married, but also a few more besides?

On his return from Spain, Orwell declared: “I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in socialism, which I never did before.” After his journey to Wigan Pier, when he first joined the socialist cause, he was merely devoting himself to a dream. But now, since Spain, he knew: socialism was actually feasible; for a short, unforgettable time, it had been a living reality, in which he took a direct part and found his place. However, together with this overwhelming discovery, he also met for the first time, face to face, with the totalitarian enemy: the Stalinists for whom the possibility of an authentic socialism was to be feared far more than the triumph of fascism, had hastened to wreck this revolutionary experiment and to massacre its participants — as a result, Orwell who had barely survived the wound he had received fighting the Fascists on the battlefront, was nearly assassinated by the agents of Moscow back in Barcelona!

It is in Spain that Orwell found decisive confirmation of his twofold commitment: for socialism, against totalitarianism. His formative years were over at last, he had found his definitive stand. From then on, his life became entirely subordinated to his writing, which death came prematurely to interrupt some twelve years later. (Contrary to common belief, Nineteen Eighty-Four is not Orwell’s spiritual testament: it became his last book only by a chronological accident. Death caught him by surprise; he knew that he was gravely ill, but still believed that he had at least a few more years ahead of him — actually, he felt so confident at the time that he remarried with a beautiful young woman and began to plan a new novel.)

Orwell’s antitotalitarian fight was the corollary of his socialist convictions. He believed that only the defeat of totalitarianism could secure the victory of socialism. This attitude which he constantly reaffirmed in his writings seems to have strangely escaped the attention of some of his admirers. For instance, in Europe and in America, we now see neo-conservatives who try to exploit his image for their own particular purposes; by making selective use of his writings they wish to show that, were he alive today, he would probably be the most eloquent spokesman of their movement (an outrageous example of this kind of manipulation can be provided by a recent article by N. Podhoretz*). Of course, this annexation of Orwell by the New Right does not reflect so much a conservative potential in his thought, as the persisting stupidity of the progressives, who, instead of applying themselves at last to reading and understanding him, are allowing the enemy to confiscate their best writer.

* Reprinted in Quadrant, October 1983. [China Heritage note: Originally published as If Orwell were alive today, Harper’s Magazine, January 1983, pp.30-37. See also Christopher Hitchens, For George Orwell, Grand Street, Vol.3, No.2 (Winter, 1984), pp.125-141; and, Christopher Hitchens and Norman Podhertz, An Exchange on Orwell, Harper’s Magazine, February 1984.]

Orwell, it is true, could be at his most ferocious when dealing with his own comrades. Should this make us conclude that, given the time, he would eventually have abandoned socialism? Actually, the very wrath with which he scourged the hypocrisy, the cowardice and the silliness of the Left, tellingly reveals the depth and sincerity of his own commitment. It is precisely because he took the socialist ideal in earnest, that he could not tolerate to see it betrayed by clowns and crooks. (Otherwise, if we were to follow the logic of the conservative commentators, should the anticlerical sarcasms of Pascal and Bloy make us question their religious faith?)

It is also true that, on some of the most urgent problems of our time — totalitarianism, pacifism — Orwell’s views are fairly close to those of the new conservatives. So what? How could this turn him into a right-winger? I can disapprove of cannibalism, or support vaccination against cholera — if it so happens that Fascists share my views on these particular issues, does this make me a Fascist?

Of course, no one could deny that Orwell’s socialism presented a few paradoxes. He entirely ignored Marxist theory; he had total (and fully justified) contempt for a large part of the socialist intelligentsia; he cursed the communist experiment in its entirety; he believed that “all revolutions are failures”. With all that, the fact that he persisted with such obstinacy in affirming that he was a “socialist” may indeed appear somewhat disconcerting; in a way, it seems akin to the attitude of some of our enlightened churchmen of today who deny Christ’s divine nature, who doubt the authority of the Scriptures, who question the existence of God — and yet insist that they should be called Christians.