Translatio Imperii Sinici

In the speech translated below Wang Ke’er 王珂兒, a first-year student in senior high school, confronts the topic of 祖國 zǔguó, the ‘mother-/ fatherland’. The text of Wang’s speech was circulated online in October 2014, although assiduous official Net-Nazis scrubbed it from the Internet as quickly as it spread. It resurfaced again in early 2019. This translation has been made as part of China Heritage Annual 2019, the theme of which is Translatio Imperii Sinici, or ‘the inheritance of empire’.

In the 2019 China Heritage Annual we focus not merely on the incipient ‘Red Empire’ of the Xi Jinping era — a topic discussed at length by Tsinghua Professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 — but also on the ideas, habits, cultural expressions, as well as the burdens of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which still powerfully influence the Chinese world.

Here a high-school student, someone who gives voice to what we call ‘Other China’ — that is a world of ideas and hopes that is not entirely dominated by the Communist party-state, or Official China and its discursive habits — mulls over the malign influence of the dynastic past while addressing the future with a measure of optimism. In doing so, Wang Ke’er also confronts the ‘China Dream’, that grab-bag concept of Xi Jinping and his propagandists. Wang tells her audience that her dreams are of a different order; they have far more in common with outspoken thinkers like Xu Zhangrun than with the droves of Party hacks and their fellow-travelers in mainland China, Hong Kong and overseas who parrot official formulations. Wang’s comments make a mockery of the Communist Party’s risible, ahistorical claims about the longevity of ‘China’ and its supposedly millennia-long story of unity, peacefulness, abstract spiritual continuity, national pride and ethnic harmony.

By alluding to the dynastic past — and in choosing to discuss particular dynasties — the speaker also offers a subtle critique of ‘Snow’ 沁園春 · 雪, Mao Zedong’s most famous poem, the second stanza of which reads:

This land so rich in beauty

Has made countless heroes bow in homage.

But alas! Qin Shihuang and Han Wudi

Were lacking in literary grace,

And Tang Taizong and Song Taizu

Had little poetry in their souls;

And Genghis Khan,

Proud Son of Heaven for a day,

Knew only shooting eagles, bow outstretched

All are past and gone!

For truly great men

Look to this age alone.

江山如此多嬌,

引無數英雄競折腰。

惜秦皇漢武,

略輸文採;

唐宗宋祖,

稍遜風騷。

一代天驕,

成吉思汗,

只識彎弓射大雕。

俱往矣,

數風流人物,

還看今朝。

— ‘For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone’

China Heritage, 27 January 2018

In her remarks, Wang lists these dynasties and wonders how she should relate to them today. And, when she goes through a list of famous modern political thinkers and leaders, she even cheekily employs a line from Mao’s poem — ‘All are past and gone’ 俱往矣 — before telling her classmates that it is up to young people like her, and them, to challenge the past and change the future.

Some readers have questioned whether this succinct and sophisticated argument was really written by a seventeen-year old in the People’s Republic. We leave it to readers to judge for themselves, although our experience would indicate that such voices from The Other China — insightful, sardonic yet uplifting — are not particularly rare, nor should they be ignored.

Equally, it is worth noting the kinds of criticisms directed at Wang’s views. One critic commented:

Students like Wang Ke’er are proof of the failure of our educational system. They only learn historical data points and material that is useful when taking exams. These children learn scraps of information about historical personages and incidents, but they aren’t apprised of the background or significance of those historical events. In this particular case, Wang can’t even explain clearly [the meaning of] the term ‘Fatherland’. It’s little wonder that students are concerned about the kind of education they are receiving.

造成王珂兒這樣的學生,全在於教育的失敗。教育只教孩子歷史的知識點和考試的內容,孩子們只知道一些片面的斷章的事件和人物,而不知道歷史的背景和事件的意義。連祖國一詞都解釋不清楚,可見當今學生之學習是何等擔憂。

— 正成, ‘写给王珂儿并答《假如我活了两千岁,

我的祖国是谁?》’, 7 October 2015

***

祖國 zǔguó literally means ‘the land of one’s ancestors’ or ‘patria’. According to patriarchal tradition, ancestors were regarded specifically as belonging to the male line of a clan or family. Therefore the term 祖國 zǔguó — a modern expression adopted from Japan — should be rendered as ‘Fatherland’. Aware of the Nazi-era odium associated with ‘Fatherland/ Vaterland’, however, China’s state media has long preferred to use the word ‘Motherland’ when translating 祖國 zǔguó. This is a term that is useful in other ways, in particular as a result of its associations with the Russian родина rodina, which was widely employed in the Stalinist-infused propaganda that was common among the Chinese Communists from the 1940s.

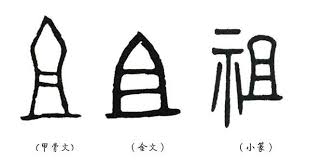

Although in English the word ‘Motherland’ enjoys positive associations related to the concepts of nurturing, birth and progeny, we would note that the primary element in 祖 zǔ, as in 祖國 zǔguó — ‘Father-/ Motherland’ — is 且, a stylised penis.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 June 2019

***

If I Were Two Thousand Years Old

What Would I Call My Motherland?

假如我活了兩千歲,我的祖國她是誰?

Wang Ke’er

王珂兒

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

This is the text of a speech made by a [seventeen-year-old] female student during a high-school speech day on the theme of ‘Our Deep Love for the Father- /Motherland’. This student’s understanding of things is far more sophisticated that that of the majority of her elders. Her remarks reflect positively on the youth of this country and offer hope for the future of China itself. 編者按:一所高中舉辦「熱愛祖國」的主題演講,這是一位少女的演講稿,其清醒認識超過我們大部分成年人,中國下一代有希望! 中國有希望!:

Teachers, Classmates: Salutations!

My name is Wang Ke’er and I’m in the first year of senior middle school, class #6. The topic I’ve chosen to address today is ‘If I Were Two Thousand Years Old, What Would I Call My Motherland??’

In my speech I will not resort to the kind of grandiloquent or emotive language that we have previously heard. I have my own ideas about what the word ‘Motherland’ means to me. I feel that our society doesn’t want for knowledgeable people, but there’s a scarcity of individuals who can think for themselves.

老師們、同學們、大家好:我是高一(6)班的王珂兒,我今天的演講題目是《假如我活了兩千歲,我的祖國她是誰?》我沒有他們慷慨的語調,也沒有他們激揚的熱情,對於「祖國」二字,我有的是我自己的思考,我覺得我們社會不缺有知識的頭腦,缺的是有頭腦的人。

And what I’ve been thinking is this: If I were two thousand years old, what would I call my Motherland?

— In the time of the Han dynasty [206 BCE-220 CE], for instance, it would be ‘Great Han’, a political power known by that famous line: ‘Regardless of how far flung they may be, any who dare encroach upon my territory, will perish at our hands’.

— If I lived in the Tang-era [from the seventh to the tenth centuries] my Motherland would be the ‘Great Tang’, a dynasty celebrated for being able to attract supplicant peoples from distant lands.

— In the Song [960-1279] my homeland would be the ‘Great Song’, a dynasty with advanced technical knowhow and a prosperous economy.

— If I was living in the time of the Yuan dynasty [1279-1368], which was ruled over by the Mongols, I’d be a low-caste underling eking out an existence under the iron hoof of the invaders. But would my Motherland have been the ‘Great Yuan’? Would I have loved it as my homeland?

— Or take the Qing dynasty [1644-1912]. The Manchus who established the Qing butchered their way through the Great Wall and executed [all male] subjects who refused to shave their forelocks and grow long queues [as a sign of their submission]. The Manchu-Qing rulers carried out the Ten-day Yangzhou Massacre [of 1645], one that puts the murderous Nanjing Massacre [of countless civilians in the Republican-era capital by the Imperial Japanese army in 1937] in the shade. Would the ‘Great Qing’ really have been my Motherland? And how would I have been able to love such a land?

I’ve gradually come to understand the fact that, regardless of who dominates your Mother by force, you’re expected to treat them as though they are your Father; but to do so, aren’t we just debasing ourselves? Classmates, sometimes it even occurs to me that if the Japanese invasion of our China had succeeded, wouldn’t we now all be chanting ‘Tennō banzai!‘ [Long Live the Emperor of Japan]?

我在想:假如我活了兩千歲,我的祖國她是誰?在漢朝,我的祖國是大漢,犯我強漢者雖遠必誅的大漢;在唐朝,我的祖國是大唐,萬邦來朝的大唐;在宋朝,我的祖國是大宋,那個科技領先,經濟繁榮的大宋。在元朝,蒙古鐵蹄把我們踐踏為四等公民,我的祖國是大元嗎?我應該愛她嗎?在清朝,滿人從關外殺入,留頭不留發,留發不留頭,揚州大屠殺讓南京大屠殺都黯然失色,我的祖國是大清嗎?我該如何去愛她?時間長了,漸漸地我們認了,誰霸佔了你的母親,你就認他做父親,我們犯賤嗎?有時候我在想,如果當初日本佔領了我們中國,同學們,今天我們會歡呼「天皇萬歲嗎」?

I’m truly confused: if I had really been alive over the past two thousand years, I honestly don’t know who or what my Motherland would be. However, in my heart of hearts, I do know there is a true Motherland, one in which people enjoy equality and justice; and it is a place where people don’t constantly feel aggrieved.

- This heartland of mine is one lets you both be a winner — for when you win you will be able to do so with confidence and peace of mind — as well as a loser — when you lose you could be allowed to do so with humble acceptance and honest acknowledgment;

- This heartland of mine can unfurl its wings and take you in its secure embrace whenever it is necessary;

- This heartland of mine fills you with hope, no matter how difficult your life may be.

Germany had its Karl Marx, while Russia produced Joseph Stalin. America boasts of George Washington and England too of Winston Churchill. All are past and gone. Today we, the young people of the world, have a responsibility. [For, as the Qing-era reformer Liang Qichao wrote in his ‘Paean to Youthful China’:]

Today’s responsibility lies with the youth. If the youth are wise, the country will be wise. If the youth are wealthy, the country will be wealthy. If the youth are strong, the country will be strong. If the youth are independent, the country will be independent. If the youth are free, the country will be free. […] If our young people are more heroic than the rest of the world, China will be more heroic than the rest of the world. [For more on this song and its place in official youth culture today, see Homo Xinensis Militant, China Heritage, 1 October 2018 — trans.]

On our watch, the watch of China’s youth, we must strive to build a country that is better than ever before; a country that truly deserves the deep love and reverence of each and every one of us; a country with a democracy that will be the envy of the Americans; a country possessed of technological knowhow that will be the envy of the Germans; a country of plenty that will be the envy of the Japanese; a country that is so honest and uncorrupt that even the Singaporeans will be impressed.

Ours will be a country that is a land of stunning achievement, a Motherland of which I can truly be proud, a place that is worthy of being a Fatherland that will never be forgotten no matter how many generations pass or how many descendants there may be trailing into the distant future.

如果我活了兩千歲,誰是我的祖國,真的讓我很迷茫。

我的心中有個祖國,那是一個公平、公正、沒有憋屈的地方;我的心中有個祖國,一個讓你贏,贏得坦坦蕩蕩,輸,輸得心服口服的地方;我的心中有個祖國,她隨時都可以展開翅膀給你保護的地方;我的心中有個祖國,無論你過的多艱難,都讓你心中充滿希望的地方。德國出產馬克思,俄國出產斯大林,美國出產華盛頓,英國出產丘吉爾,俱往矣,今日之責任,不在他人,而全在我少年。少年智則國智,少年強則國強,少年獨立則國獨立,少年雄於地球則國雄於地球。我等少年手裡必會有一個升級版的祖國,她讓每一個人都在心中深深地愛上她,她讓美國羨慕我們的民主,讓德國羨慕我們的技術,讓日本羨慕我們的民富,讓新加坡羡慕我们的清廉。看他日,我的祖国,必是一个朗朗的乾坤,一个让后世子孙千秋万载也忘不掉的祖国!

The China Dream? In the past, the Chinese had Three Old Dreams:

- They dreamed of having a Decent Ruler — a Good Emperor — one who had a meaningful and positive response to the problems they faced. A ruler who was beneficent to all;

- They dreamed of Untainted Officials. Even if they couldn’t have a truly Good Emperor, they would dream about there being at least one unsullied official, one who was clean and who had the personal daring to give voice to the concerns of the common people when addressing the ruler; an official who had the courage to challenge the Emperor;

- They dreamed that if there was no hope for even one Untainted Official there would be a heroic Knight-errant, someone who could seek revenge on their behalf.

中國夢,中國人的三個舊夢:第一個夢叫明君夢,就是希望有個好皇帝,希望一切問題有現成的解答,一切好事有統治者恩賜;第二個夢叫清官夢,如果皇帝指望不上了,就希望有一位清官,兩袖清風,還能犯言直諫,敢於在太歲頭上動土;第三個叫俠客夢,如果清官也指望不上了,就希望有一個俠客來報仇雪恨。

Today, the Chinese have Three New Dreams:

- The First Dream is for Freedom, to be freed from the oppression of monolithic state power and the burden of autocratic rule, along with the repressive behaviour of the New Nobility;

- The Second Dream is for Human Rights, that is to enjoy equal rights and an environment without some privileged group that lords it over everyone, creating impotent resentment; and,

- The Third Dream is for Constitutional Government, a kind of political arrangement that is underwritten by a constitutional order in the interests of all of the people; a constitutional rule that is a true expression of the will of the whole people which allows all to participate in politics equally; a constitutional order that will determine just how things can and should be done.

中國人的三個新夢:第一個夢叫自由夢,就是從一元化高壓下解脫出來,不再受專制統治、權貴橫行的壓迫。第二個夢叫人權夢,就是人人都能享有平等的權利,不再有任何高居普通民眾之上的特權叫人恨而無奈。第三個夢叫憲政夢,就是全民制憲,全體國民一起來制定基於人人平等基礎上的根本大法,並且一切依此辦事。

The Three Old Dreams were fantasies embraced both by [dynastic-era] officials and subjects alike; they were a kind of self-stupefaction, reflecting the stuff of nightmares that haunted everyone for millennia. Their effect was to pacify the people, to make them submit meekly thereby allowing the power-holders to do as they pleased, to enjoy things as they wished, to kill and maim at random while vouchsafing their eternal right to rule.

三個舊夢是臣民消極被動的黃粱美夢,是愚民政策給臣民帶來的千年噩夢,只會使民眾變成溫順的綿羊,任憑統治者作威作福,宰割屠殺,永遠統治。

The Three New Dreams are the inevitable product of modern mercantile civilisation. They are an expression of social enlightenment, a symptom of a popular awakening, the result of the struggle and sacrifices of people of conscience and hope. They are dreams that will, one day, be our woken reality.

三個新夢是商業文明的必然要求,是社會啓蒙的體認,是全民大覺醒的表現,是志士仁人浴血奮戰的結果,而且一定會到來。

***

***

Source:

- 王珂儿, ‘假如如我活了两千岁,我的祖国她是谁?’, CND (China News Digest), 2015年2月26日 (reprint)

Critique:

- 正成, ‘写给王珂儿并答《假如我活了两千岁,我的祖国是谁?》’, 7 October 2015