Spectres & Souls

Chapters in the 2021 issue of China Heritage Annual: Spectres & Souls, have appeared throughout the year, and which will overlap into 2022, we posited that many of the spectres and shades, as well as the enlivening souls and lofty inspirations, that assert themselves both in China and the United States in 2021 may present an even more compelling aspect when considered in the context of the 160-year period starting in 1861. In November that year, the successful Xinyou Coup 辛酉政變 at the court of the Manchu-Qing dynasty that had ruled China for two centuries ushered in a short-lived period of rapid reform, one that, in many respects continues to this day, even as it falters.

In February 1861, seven slave-owning states broke with the Union that had been established under the Constitution of 1787 resulting in a four-year civil war. The successful conclusion of that war saved the Union, but the failure of the subsequent era of Reconstruction had profound ramifications for the state of that union, and the United States of America generally.

The successes and failures of that era are, in January 2021, more relevant than they have been for 160 years as a new president appealed to ‘the better angels’ of the nation, echoing the words of Abraham Lincoln who, in his first inaugural address, delivered at The Capitol in Washington on 4 March 1861, declared:

‘We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.’

In early 2021, there were some who believed that the ‘better angels’ both of America and of China could possibly usher in a period of concord, if not amity. Readers of China Heritage will, however, be familiar with our view that simplistic yearnings for positivism ignore both human nature and human history.

Spectres & Souls began with a pair of introductory essays:

- ‘Better Angels, Persistent Demons — Part I’, China Heritage, 20 January 2021

- ‘Better Angels, Persistent Demons — Part II’, China Heritage, 31 January 2021

We conclude the year by reprinting an old essay by Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波, one of China’s better angels. His words echo with disturbing relevance, some thirty years after he wrote them, and reading them today the profound sense of loss resulting from his cruel death in custody murder overwhelms us anew (see ‘The Pity of It’, 14 July 2017).

***

We are, yet again, grateful to Lois Conner for her kind permission to use work from her series ‘Shooting 5th Avenue’ (2020-2021), a project supported by Robert Rosenkranz and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

New Years Eve

31 December 2021

***

More on and by Liu Xiaobo:

- Liu Xiaobo interview with Bai Jieming (Geremie Barmé), December 1986, subsequently published under the title 中國人的解放在自我覺醒——與個性派評論家劉曉波一席談 in The Nineties Monthly 九十年代月刊, March 1987

- G. Barmé, ‘Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989’, 1990 & in Chinese at: 忏悔、救赎与死亡:刘晓波与八九民运, 石默奇译

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Tragedy of a “Tragic Hero” ’ and ‘At the Gateway to Hell’, translated by Barmé in Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Random House, 1992

- G. Barmé, China’s Promise, China Beat, 10 January 2010

- Barmé interviewed by Philippe Grangereau on Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Prize, Libération, 8 October 2010

- Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems, Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, Liu Xia, eds., Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

- 劉曉波文選, 獨立中文筆會 (select essays by Liu Xiaobo, in Chinese)

- ‘Mourning’, 30 June 2017

- ‘The Pity of It’, 14 July 2017

- An Interview, 15 July 2017

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Specter of Mao Zedong’ (1994), reprinted in ‘Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong’, 20 September 2021

Further Reading:

- Liu Qing 刘擎, ‘Can China Think Without America? 离开美国我们就无法思考吗?’, The China Story Journal, 4 February 2013

- Less Velvet, More Prison, China Heritage, 26 June 2017

- Xu Zhiyuan, The Anaconda and the Elephant, China Heritage, 28 June 2017

- Václav Havel, ‘History as Boredom — Another Plenum, Another Resolution, Beijing, 11 November 2021’, China Heritage, 14 November 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty’, China Heritage, 1 October 2021

***

The Inspiration of Liu Xiaobo

Translator’s Introduction

Geremie R. Barmé

In March 1989, Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波, 1955-2017) was a visiting scholar at Columbia University when he wrote the following essay. It was composed as the conclusion to a series about Chinese intellectuals and China’s traditional autocracy that he worked on in New York. At the time of his death in a mainland Chinese jail in June 2017, some three decades later, he was China’s most famous political prisoner and a Nobel Prize laureate.

Raised in the northeast of the country, Liu first came to prominence in Beijing in 1986 when he was still working on his doctoral dissertation in philosophy. He courted controversy by publicly decrying the prevalent smug self-satisfaction about the cultural achievements that had been attained since the Cultural Revolution and he was one of the first members of a younger generation of intellectuals to argue publicly that the Chinese culture was in deep crisis and that none of the established figures writers, scholars, or critics would confront the fact.

Liu aimed virulent criticism at the traditional role of intellectuals in China; although at times he somewhat simplistically equated the ‘communised’ intellectuals of the post-1949 period with the literati and court scholars of imperial times. His acerbic critiques extended to contemporary intellectuals, literary figures of whom he became increasingly dismissive. He spared neither the reformist cultural establishment nor the cultural underground in his numerous speeches at forums and universities. He offended people across the political spectrum but gained an enthusiastic following among university students.

In August 1988, Liu made his first trip overseas. He initially accepted an invitation to go to Norway to give a series of lectures at the University of Oslo and to attend an academic conference. Three months later he was invited to the United States. During his stay in both Europe and the United States (Honolulu and New York), he moved away from his narrower literary concerns and began writing prolifically on Chinese politics. One of the essays he wrote during this time, Contemporary Chinese Politics and Chinese Intellectuals 中國當代政治與中國知識分子, was serialized in the Hong Kong publication Cheng Ming 爭鳴 in 1989-1990 and published in Taiwan as a book in mid-1990. The essay published here is the postscript to that work. It was written shortly before Liu became involved in the protest movement in early May 1989.

***

Liu’s stay in the West unsettled him deeply. As this essay shows, it helped inspire him to move from the relentless acerbity of his earlier work toward a more profound and self-critical reflection on the broader issues facing China. He also became convinced that only through action and sacrifice could a Chinese intellectual like himself find redemption for the ‘sins’ of his or her silent complicity in party rule.

Xiaobo was particularly outraged by the fawning posturing of some of China’s most prominent ‘intellectual dissidents’ when former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang died on 15 April 1989, an event that led directly to the mass protest movement of 1989, one that saw popular protests in dozens of Chinese cities.

Liu wrote that ‘The depth of sincerity of emotion [among the intellectuals mourning Hu’s passing] is redolent with an air of servitude normally seen only in the relationship between loyal mandarins and their emperor.’ He noted with irony that those who were mourning:

‘had always been extremely grateful to Hu for the way, directly and indirectly, he used his position and power to protect them or allow them greater freedom of speech. What developed was the ideal relationship between an enlightened ruler and his enlightened thinkers … a mutually beneficial relationship.’

He concluded his lambasting critique by declaring that ‘either you go back and take part in the student movement, or you should stop talking about it.’ He cut short his stay in America and returned to China just as many of the most prominent Chinese intellectual dissidents he had been talking about gathered in Bolinas, California, for a symposium (see On The Eve: China Symposium ’89, 27-29 April 1989).

***

Liu was highly critical of the movement in Beijing, even before he went back. He saw it as following the same, tired pattern of political agitation common in China since the 1910s — a period of street marches, sloganeering, and popular enthusiasm, invariably followed by exhaustion, silence, and despair. Nonetheless, he believed that it was important to support the protesters and stand by them. The concept of personal guilt and the need for redemption that become a feature of Liu’s thinking informed his actions during the movement. Apart from providing logistic support for the students, he also wrote a number of samizdat pamphlets, which are among the most sophisticated works of the period. (Elsewhere, I have written in detail about Liu’s involvement in the protest movement and its significance, see ‘Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989’, 1990).

The hunger strike Liu Xiaobo led on 2 June in support of the students occupying Tiananmen Square was brought to an abrupt end in the early hours of 4 June as the Chinese army crushed the six-week old protest movement with devastating violence. Liu joined his fellow hunger-strikers — Hou Dejian, Zhou Duo, and Gao Xin — in helping negotiate a peaceful withdrawal of the remaining students from the center of the square. He was detained by plainclothes policemen on 6 June. Following the Beijing massacre, the Chinese government denounced Liu Xiaobo as a leading ‘instigator of turmoil’. He was also accused of links with Hu Ping and the Chinese Democratic Alliance in the United States, and of being their agent in Beijing. (In the United States, he had certainly met Hu Ping and his fellow dissidents, but he had actually distanced himself from the Alliance, wary of its endless factional strife.) Liu was formally charged in late 1990 and tried in January 1991. Although the court found him guilty of ‘counter-revolutionary propaganda and instigation’, and of ‘attempting to overthrow the people’s government and the socialist system’, in view of his efforts to get the students to leave Tiananmen Square on the morning of 4 June it ordered his release.

Chinese government criticisms of Liu focussed above all on his supposed ‘national nihilism’, something for which earlier critics, many of whom are now in exile themselves, had previously condemned him. Such labels have always been standard issue for dissident intellectuals in the socialist world. The following essay can be read as Liu’s reply to these accusations. It is a succinct, if abstract, meditation on the question of nationalism, the abiding dilemmas of Chinese intellectuals in exile, and the nature of independent intellectual activity.

Liu’s comments on God and original sin may seem strange coming, as they do, from a mainland Chinese. However, the discussion of ultimate values, guilt, and redemption is by no means foreign to Chinese intellectuals or the modern Chinese intellectual tradition.

Liu is one of the few contemporary Chinese thinkers to see exile as an existential state, a condition of the 20th century, rather than the unfortunate fate of the Chinese alone. His awareness and self-doubt make him a rare figure; he has seen beyond mere intellectual debates and political strategies to the essence of the Chinese dilemma, which the June 1989 massacre and developments in the erstwhile international socialist camp have only tended to exacerbate. His was a powerful and unsettling voice, not only for the Chinese authorities, but even for his comrades.

***

Liu Xiaobo’s name along with his work, much of which is as relevant today as it was twenty or thirty years ago, have long been banned in the People’s Republic. In Xi Jinping’s China the latter-day scholar-official and ‘thought-leading’ courtiers — the kinds of contemporary ‘literati’ 文人 wén rén and 書生 shūshēng that Liu Xiaobo mocked decades ago — now presume to pass judgement on him and his achievements. In fact, those who dominate the academic and publishing worlds of Xi Jinping’s China, and many of those who still advertise themselves as ‘liberal thinkers’, do not even regard Liu as an bona-fide ‘Chinese intellectual’ 中國知識分子 (a specific category of ‘knowledge-producers’ best not confused with independent-minded thinkers found in other climes). As I have pointed out elsewhere, this is a particular caste; they are a ‘Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia’ 皮毛知識界 painstakingly nurtured by political fiat and a decades-long process of acculturation, one that melds seamlessly with post-Song-era practices (for more on this topic, see ‘Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty’, China Heritage, 1 October 2021). Readers who are interested in gleaning the sparse and unedifying fields of self-serving ratiocination can consult the excellent Reading the China Dream blog. Therein, and in China’s state media and academe more generally, one can observe what ‘intellectual diversity’ looks like when, to use Steve Bannon’s deathless expression, you ‘flood the zone with shit’.

(Some of the material in the above is based on my 1990 introduction to the following translation.)

***

The Inspiration of New York:

Meditations of an Iconoclast

Liu Xiaobo

translated by Geremie Barmé

During the cultural debate of the past years I have consistently maintained the stance of an anti-traditionalist. I always thought my theories were up to international standards; now l realize that I have been deluded by deep-seated arrogance. This trip overseas has forced me to wake up to myself.

There may be some merit in my anti-traditionalism, but only if it is considered within the context of China or with a view toward transforming China. That’s because China and her culture are truly moribund, ossified, decrepit, and corrupt. To find the determination, strength, and wisdom necessary for self-reform requires us to experience a deep-felt sense of shame over our backwardness, something which can only come from the threatening stimulation and challenge afforded by [contact with] an entirely different civilization. As a basis for comparison, Western culture clearly throws into relief the general nature and myriad weaknesses of Chinese culture. Against it we can measure our decrepitude. As a form of constructive wisdom, Western culture can inject a new life-force into China.

On the other hand, if your concern is with the fate of humanity as a whole or with the future of the world, or even with individual fulfillment, my anti-traditionalism seems completely meaningless. My concerns have been both narrow and superficial: those of a Chinese preoccupied with the problems of China. There is nothing in my work that reflects a concern for humanity as a whole or for the future of the world, let alone the tragic nature of existence itself; equally, [in my work] there has been no transcendental concern for the need of each individual to find self-fulfillment. The value of my anti-traditionalism exists only within the context of the worthless cultural rubble of China. My failings are all too obvious: narrow nationalism and a blind fawning before the West.

Since my involvement in the cultural debate, I have been labeled an advocate of “total Westernization” and a “cultural nihilist.” In fact, everything I have said about Chinese and Western culture has been as a nationalist wanting to reform China. It has had nothing to do with “total Westernization.” In my opinion, the most important feature of Western culture is its tradition of critical rationalism. Real “Westernization” would consist not only of a critique of Chinese culture, but a critical re-evaluation of Western culture as well, a concern with both the fate of mankind as a whole and that of the unfulfilled individual. It would be a critical re-evaluation based on a commitment to “knowledge for its own sake,” a commitment to a complete, self-sufficient ontological and value system that transcends mere utilitarian values. Because my use of Western culture has been solely aimed at transforming Chinese reality, I have remained a typically self-referential Chinese and not a “Westernizer.” This China-orientation has limited my interest in and consideration of higher questions (as it also limits the majority of Chinese intellectuals — it’s the reason why modern China has not produced great thinkers has a lot to do with this narrow nationalism.) I have been incapable of concerning myself with the fate of humanity and therefore of coming to grips with international Western culture; I have also been unable to achieve personal, religious transcendence based on self-realization, let alone reject all worldly inducements and engage in a pure exploration of knowledge. I am too utilitarian, too practical; I remain caught up in the vulgar concerns of the problems of Chinese reality.

This has led me to think of Lu Xun, a man whose tragedy lay in the absence of transcendental values, a tragedy of godlessness. His understanding of the tragic nature of the human condition went beyond an outward despair for the condition of society to become an internalized angst. We can chart the course of this development in Lu Xun from [the 1923 short story collection] The Cry to [the 1926 collection] Wandering. In [the 1927 volume of prose poems] Wild Grass, Lu Xun achieves a profundity unmatched by any of his other writings.

The Lu Xun of Wild Grass cannot be judged by any mundane standards. He had moved from his earlier penetrating criticisms of Chinese reality and culture toward self-examination. Only transcendental values could have helped him overcome the deep-seated and weighty burden of psychological disintegration and depression [expressed in this book]. He reveals his hopelessness, a sense that all that lies ahead is the grave. It is here that God’s direction is needed. Unable to find a standard that went beyond utilitarian worldly values, Lu Xun found it impossible to move beyond Wild Grass.

Indeed, Wild Grass represents both the high point of Lu Xun’s career and his final resting place. After this he could no longer tolerate the loneliness, solitude, and hopelessness. He couldn’t bear the endless intellectual doubt. In the end he struggled free, but not by finding some transcendental value. Returning to vulgar reality, he spent his time engaged in futile polemics with a pack of mediocrities. Having become thus entangled, he surrendered to the mediocre. Or to put it another way: after overcoming the limitations of Chinese reality and culture through his critiques, Lu Xun found himself alone. Yet he could not bear to face the unknown world by himself; he could not cope with the solitary terror of the grave. He did not wish to engage in a transcendental dialogue with his own soul under the gaze of God, and it was at this point that the traditional utilitarianism of the Chinese literati raised its ugly head. Bereft of transcendent values, Lu Xun could only regress. He only enjoyed “struggling with the dark” in the dark, but he could not overcome the darkness itself. Lu Xun had been profoundly influenced by Nietzsche, yet there was a great difference between him and Nietzsche: after having lost faith in man, Western culture, and himself, Nietzsche was able to use the reference of “superman” to achieve a personal sublimation. Lu Xun failed to find any transcendental values to help him continue, and so once more he fell back into the reality which he had previously rejected in disgust.

This brings me to another question: why have so many outstanding writers in exile from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe appeared in Western Europe, whereas there have been none from China? Why is it that famous Chinese cultural figures, once in exile, achieve nothing? Certainly, there are linguistic barriers, but I feel a more important reason is that Chinese cultural figures are blinkered. All they care about is the “China problem.” They are too utilitarian: all they are concerned about is practical values.

Chinese intellectuals lack the motivation to transcend themselves as well as the spirit that motivates individuals to pit themselves against society as a whole; they lack the internal fortitude required to cope with solitude and the courage and curiosity to face an unfamiliar and unknown world. Chinese intellectuals can only survive in their own, familiar surroundings, bathed in the limelight and applause provided by the ignorant masses. This is particularly so in the case of the famous, who cannot bear to abandon the fame they have achieved in China and start all over again in a foreign land. This “China-fixation” is virtually inescapable; its most outstanding feature is the absence of real individuality.

Thus, China’s leading cultural figures cling to nationalism with all their might. They do not see themselves as individuals confronting reality, they do not live for the realization of true self-worth. Their existence is determined by a false sense of worth that derives from an adoring and moronic mob, they live for the hallucinatory sense of superiority they get from playing the Messiah.

In China, their every action and word attracts the respectful attention of society. Overseas, they are alone, unable to attract doting gazes. Apart from the indulgence of a handful of foreigners with an interest in China, nobody else takes much interest in them. What it takes to be able to cope with a solitude bereft of applause and bouquets is not external support, but inner strength: the talent, wisdom, and creativity of the individual. No matter how famous or how important you were in China, the moment you are placed in this new and unfamiliar world you are forced to deal with the world as an ordinary individual.

This is why I have been such an energetic advocate of Western culture, and such a virulent critic of Chinese culture. Nonetheless, I am still nothing more than a “frog in the bottom of a well,” staring up at a small patch of blue sky. Theoretically speaking, you don’t need to be incredibly well informed to engage in a self-examination and criticism of Chinese culture. In fact, you don’t even need to be creative. That’s because the theoretical constructs of which I avail myself in examining Chinese culture are givens, ready-made, and do not require any new discoveries. These theories, which Chinese intellectuals treat as profound and innovative, have been clearly explicated by Westerners; they have been around for hundreds of years in the West and are regarded today as old-hat. They don’t need us to add any footnotes to them. I think I’ll be doing well if I can achieve a passably solid and accurate understanding of them.

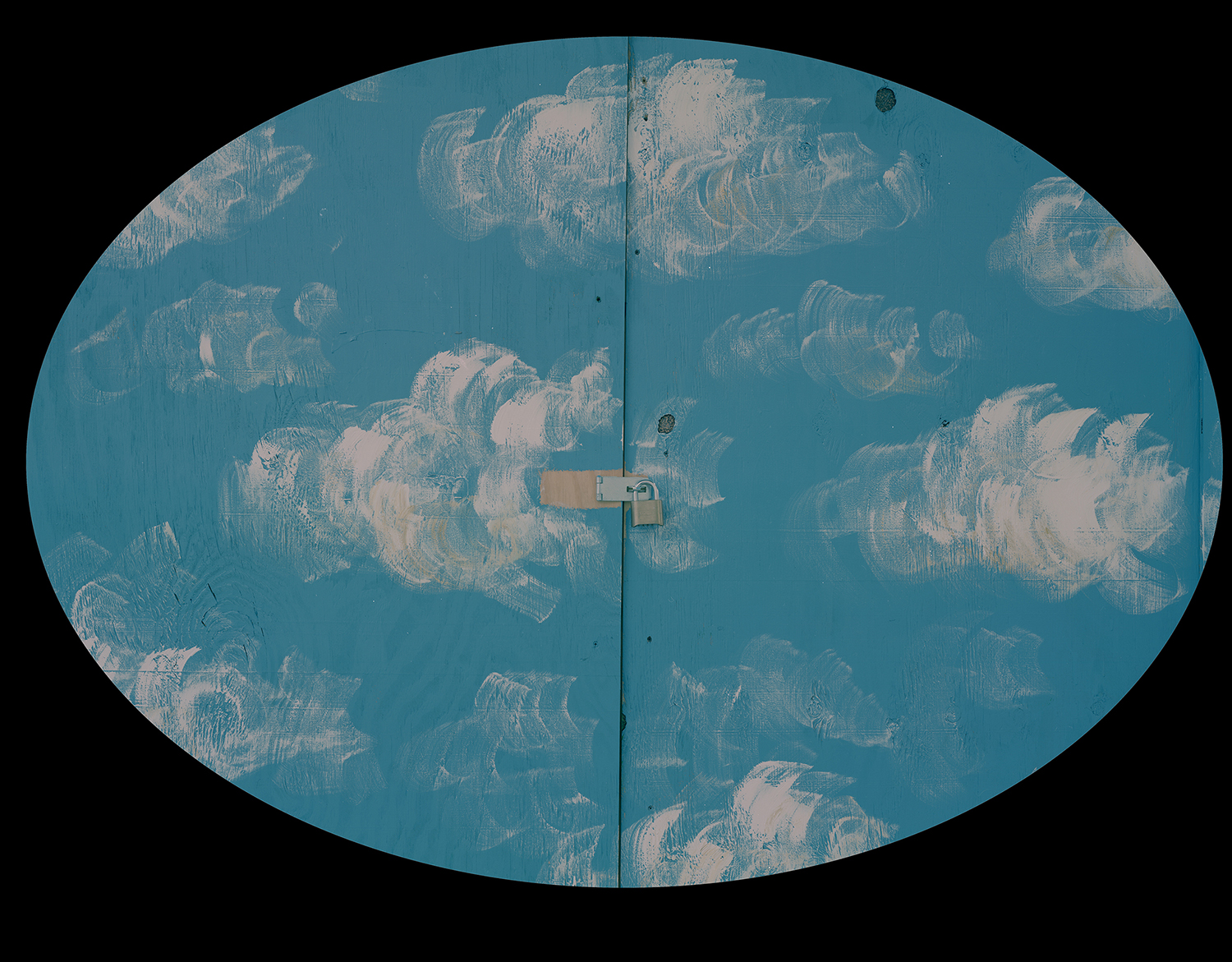

Wang Gongxin on a Batrachian Point of View

In ‘Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World’ at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, October 2017 to March 2018, the artist Wang Gongxin (王功新, 1960-) reconfigured an installation that he originally created in Beijing in 1995. At the Guggenheim he opened a skylight in the floor:

The original, Sky of Brooklyn—Digging a Hole in Beijing, consisted of a 3.5-meter “well” dug in the living room floor of the artist’s Beijing house. A television monitor at the bottom of the well showed footage of the sky of Brooklyn in a continuous loop. Wang added a soundtrack: “What are you looking at? What’s there to look at? There are a few clouds in the sky. What’s there to see?”

The artist imported his old floor tiles for the Guggenheim show and replicated the well. This time the work was called Sky of Beijing—Digging a Hole in New York, and the television monitor offered an unbroken view of the sky over the Chinese capital. Sotto voce, small-scale, discreet, Wang’s work is a welcome relief after the cacophony and bristling ambition of much of the rest of the exhibition. Wang’s bottomless well invites the viewer to reflect on two clichés: one is the notion that if you were to dig a hole straight through the earth you would end up in China; the other comes from Zhuangzi, the third-century BCE Taoist thinker who said that you can’t discuss the vast ocean with a frog at the bottom of a well for he only sees what is over his head.

— from Geremie R. Barmé, ‘China’s Art of Containment’

The New York Review of Books, 27 November 2017

When I visited the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I finally came to the realization that what l’d always considered my brilliant insights don’t really amount to much at all. Confronted by another world, I feel myself vanquished by it. For far too long I have lived cut off from the world in the barren and ignorant cultural atmosphere of China, where thought is superficial, and life itself stymied. Eyes that have grown accustomed to the darkness cannot instantly adjust to the daylight. When New York tore away all of the external embellishments and illusory fame that I had in China, I suddenly realized how weak I really was. I was incapable of immediately finding the courage to face myself; nor could I possibly engage in a dialogue with the upper strata of the international intellectual world. But defeat should be like this, thorough and pitiless; it was a far more significant experience than any of the empty accomplishments that I had achieved in China.

My position was that of a narrow nationalist trying to use Western culture to reform China. My critique of Chinese culture was based, however, on an idealized version of Western culture. I overlooked, or purposefully avoided, the limitations of the West, even those weaknesses of which I was already aware. I was therefore incapable of a higher level of critical examination of Western culture, which would focus on the weaknesses of mankind itself. All l could do was to “ingratiate myself” with Western culture glorifying it in a manner quite out of proportion to reality, as if it not only held the key to China’s salvation, but contained all the answers to the world’s problems. But now, looking beyond this, it is obvious that my idealization of the West was a way of making myself out to be a veritable Messiah. I always despised people who assumed the role of savior; now I realized that drunk on the notion of my own beneficence and power, I was playing — consciously or not — a role that I detested.

I know that Western culture can be used at present to change China, but it cannot save humanity in the long run. For the weaknesses of Western culture highlight the congenital defects of mankind. In the”Autumn Waters” chapter of Zhuangzi [the classical Taoist philosophical text] the point is made that no matter how large a river may be, it cannot be as vast as an ocean, and compared to the universe, even an ocean is minuscule. The self-confidence implied in the statement [at the beginning of that chapter) that “all beautiful things under heaven can be found in oneself” is nothing but an illusion. By pursuing this metaphor, we can say that China is backward compared to the West, while the West has its limitations within the context of humanity as a whole, and faced with the vast universe, humanity itself is but minuscule in turn. The overriding arrogance of mankind is reflected not only in the self-satisfied Ah Q spirit of China but also in the Western belief in the omnipotence of rationalism and science. No matter how strident in their criticism of rationalism those in the West may be, no matter how strenuously Western intellectuals try to negate colonial expansionism and the white man’s sense of superiority, when faced with other nations, Westerners cannot help feeling superior. Even when criticizing themselves, they become besotted with their own courage and sincerity. In the West, people can calmly, even proudly, accept the criticisms they make of themselves, but they find it difficult to put up with criticisms that come from elsewhere. They are not willing to admit that a rationalist critique of rationalism is a vicious cycle of self-deception. But then who can find a better critical tool?

***

***

As someone who has lived [nearly] all his thirty-odd years in China, I must be prepared to launch a two-pronged attack if l am to be able to reflect intelligently on larger questions. On the one hand, I must use a Western perspective to criticize Chinese culture and reality; on the other, I must rely on my own individual resources to make a critique of the West. Neither of these approaches can replace or override the other. So, while criticizing [the West for its] overemphasis on rationalism, science, and money that has led to the undervaluation of the individual, and criticizing the development of an international economic hierarchy and the weakening of opposition due to the homogenizing influence of technology and commercialization, as well as pointing out the ills of conspicuous, unreflective consumerism and the worship of wealth, along with the cowardly flight from freedom, it is vitally important to keep in mind that none of these criticisms is relevant to China. Rationalism, science, and money have only just begun to enter the Chinese consciousness, for the Chinese are still doubly handicapped by poverty and restrictions on their freedom. Just as the standards used to criticize the West are not relevant to China, equally the standards of Chinese culture cannot be used meaningfully in a critique of the West, for they would only drag the West down. Some Westerners, dissatisfied with their own culture and life, look to the East for a key to unlock the mysteries of the human condition. This is blind and misguided; it is wishful thinking. Chinese culture cannot even cope with the dilemmas facing China, let alone those of the West or mankind as a whole.

It is my belief that one of the greatest mistakes made by man in this century has been his attempt to rely on past accomplishments to overcome present problems. Neither the culture of the East nor the West, as they stand today, offers salvation. The superiority of Western culture can at most help the East achieve a modern lifestyle, but this form of progress brings with it its own tragedy. Mankind has yet to create a fresh form of civilization that can solve the population explosion, the energy crisis, the environmental crisis, and the increasing threat of nuclear war, much less overcome forever the pains and limitations of the human condition itself. No one can avoid the fact that the anxiety created by the possibility of nuclear holocaust is the subtext of all modern life. The finality of death makes a mockery of all. To be able to face this cold, hard fact while maintaining the courage to step into the chasm is the ultimate act of which man is capable.

Since the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, mankind has existed in a permanent state of exile. Western civilization is merely a stage in the course of this exile. Tragically, the “sense of original sin” that is so basic to Western culture is becoming increasingly weak, the confessional impetus increasingly atrophied. Religion has become but another form of entertainment, like rock ‘n roll. Since Jesus Christ was nailed to the cross, no one else has come forward to sacrifice himself for the sins of others. Mankind has lost its conscience. The gradual disappearance of [the sense of] original sin has set man loose from his moorings; today’s decadence represents a second fall from grace. How can a person who has no sense of sin ever hear the voice of God? From the early Middle Ages, when God was rationalized and was later made an adjunct of the power-holders, to the pre-modern period when God became humanized, to the 20th century when God has been increasingly vulgarized and commercialized, civilization has been in decline. Man has killed with his own hand the [symbol of] transcendental value. Is the transmogrification of the concept of God a proof of human advancement or its decline? If it is decline, then with the death of God does the fall of man retain any significance?

Thus I have come suddenly to the realization of impotence. I face an agonizing dilemma. I now know that in using Western values to criticize Chinese culture l have been attacking an ossified culture with only slightly less ossified weapons. I am like someone who, though partially paralyzed himself, mocks a paraplegic. Having transplanted myself into a completely open world, I am suddenly forced to acknowledge that not only am I no theoretician, but l’m not a famous person anymore. All I am is a normal person who has to start all over again from the beginning. In China, the backdrop of [general] ignorance highlighted my wisdom. My courage was thrown into relief by the cowardice of others. l appeared healthy in comparison with the congenital idiocy of my surroundings. Yet, in the United States, now that this backdrop of ignorance and failing has disappeared, so has my wisdom, courage, and vigor. I have become a weakling unable to face myself. In China, I had been living off a reputation of which 90 percent was hot air. In the West, for the first time in my life I have been faced with real and hard decisions. When a person falls from the peak of fantasy into the chasm of reality, only then does he discover that he has never climbed a peak at all, but has been struggling all along at the bottom of that chasm.

Tao Li, my wife, said the following in a letter to me:

‘Xiaobo, you may appear to be a famous Chinese rebel, but, in reality, you have made a sly pact with society. You are tolerated and forgiven. Our society envelopes you, even encourages you, while all along appearing to reject you. You are an adornment, a decoration; your very existence is a negative validation of the system.’

When I first read this passage, it left me cold. Now I realize how perceptive her comments are. I am grateful to Tao Li. She is not only my wife, she is also my most relentless critic.

There is no way back now. Either jump over the ravine to the other side, or dash myself to pieces in the effort. Faced with reality one must confront danger.

March 1989

New York

***

Source:

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘The Inspiration of New York: Meditations of an Iconoclast’, trans. Geremie Barmé, Problems of Communism, January-April 1990: 113-118. The translation is based on the version of Liu’s text published in the July 1990 issue of Ming Pao Monthly 明報月刊, it differs slightly from the version used as the postscript to his Contemporary Chinese Politics and Chinese Intellectuals 中國當代政治與中國知識分子, serialised in Cheng Ming 爭鳴 in 1989-1990 and published in Taiwan by Tangshan chubanshe in 1990. For the Chinese text, see 劉曉波,《中國政治與中國當代知識份子》後記 below

Chinese Text

The following revised text was published as the postscript of the book version of Contemporary Chinese Politics and Chinese Intellectuals 中國當代政治與中國知識分子.

***

《中國政治與中國當代知識份子》後記

劉曉波

站在中西比較的和改造中國的層次上看,這本書或許還有一定的價值,因為中國的現實和文化在世界的範圍內實在是太陳舊、太腐朽、太僵化、太衰老了,它需要一種強有力的異質文明所帶來的具有威脅性的刺激和挑戰,需要遼闊的、澎湃的汪洋大海來補托它的封閉與孤立、沈寂與渺小,需要用落伍的恥辱來激發它的自我改造的決心和鬥志。作為一種相互比較的參照系,西方文化能夠最鮮明地實現出中國文化的總體特徵和種種弱點;作為一種批判性的武器,西方文化可以有效地批判中國文化的老朽;作為一種建設性的智慧,西方文化能夠為中國輸入新鮮血液和改造中國的現實。然而,站在人類命運和焦慮世界的未來的高度上看,站在個體生命的自我完成的層次上看,這本書或許一文不值。因為它所關注的問題過於淺和狹隘──只是站在中國人的立場、基於對中國的關注,而非站在人類的立場上對世界前途的關注,更不是站在個體生存的悲劇性的立場上,對每個生命的自我完成的關注。所以,這本書的價值僅僅是相對於無任何價值的文化廢墟而言的,其低劣之處特別明顯地表現在以下兩個方面──陝隘的民族主義立場和盲目的西方文化獻媚。

一、

僅是這本書,也包括我曾經發表過的關於中國文化的所有言論,都是一種立足於中國的民族主義,而決非象有些人指責我的那樣是「全盤西化」。我認為,西方文化的最大特徵之一是批判理性的傳統,真正的「西化」不僅是對中國文化、更是對西方文化的批判性反省,是對全人類命運的關注,對個體生命的不完整的關注。而企圖借助於西方文化來重振中華民族,是典型的中國本位論而非「西化論」。這種以中國為本位的民族主義立場限制了我對更高層次的問題的思考(我想也限制了大多數中國知識份子的視野。近代中國出不了世界級的大師,也肯定有這種民族主義立場的限制)。我既不能在關懷全人類的命運的層次上與先進的、世界性文化展開對話,也不能在純個體的自我實現的層次上達至宗教性的超越。我太功利、太現實,仍然局限於落伍的中國現實和世俗性的問題。我的悲劇或許象當年魯迅的悲劇一樣,是沒有超越價值,也就是沒有上帝的悲劇。魯迅在對人生的悲劇性體驗上,已經達到了《野草》的深度,那種深刻的內心分裂需要一種超越性的價值來提升;那種無路可走、前面只有墳的絕望需要上帝的引導,《野草》時期的魯迅是任何世俗性價值也無法提升的。他已經由站在中國文化之上對中國現實的清醒批判和失望走向了對自身的批判和物望,如果沒有一種超越任何世俗利益的絕對價值的參照,魯迅的《野草》就只能既是他創造力的頂峰,也是他為自身開掘的不可跨過的墳墓。

事實正是如此,《野草》之後的魯迅再也忍受不了內心的寂寞、孤獨和絕望,走出了內心世界的掙扎,重新墜入庸俗的中國現實之中,和一群根本就構不成對手的凡夫俗子們進行了一場同樣庸俗的戰爭。結果是,與庸才作戰必然變成庸才。魯迅無法忍受隻身一人面對未知世界,面對墳墓時的恐懼,不願意在上帝的注視下與自己的心靈進行超越性的對話,傳統土大夫的功利化人格在魯迅身上筆活,於是,沒有上帝的魯迅只能墜落。魯迅深受尼採的影響,但是他與尼採的最大不同在於:尼採在對人類、對自身絕望之後,借助於「超人」的參照而走向個體生命的提升;而魯迅在對中國人、對自身絕望之後,沒有找到超越性的價值參照系,重新回到了被他徹底唾棄的現實之中。

由此我聯想到,為什麼在西歐諸國,甚至在蘇聯和東歐諸國,出現過一大批傑出的流亡作家、哲學家、科學家,而在中國沒有?為什麼中國的文化名人一流亡國外就會毫無成就?我認為,中國文化人的視野太狹隘,只關心中國的問題;中國人的思維太功利化,只關心現實人生的價值;中國知識份子的生命中缺乏一種超越性的衝動,缺乏面對陌生世界、未知世界的勇氣,缺乏承受孤獨、寂寞、以個體生命對抗整個社會的抗爭精神,而只能在他們所熟悉的土地上,在眾多愚昧者的襯托和掌聲中生活。他們很難放棄在中國的名望而在一片陌生的土地上從零開始。這是一種難以擺脫的中國情結。正是這種情結,使中國的文化名人們緊緊抓住愛國主義這根稻草不放。他們不是面對真實的自我,為了一種踏實的自我實現而活著;而是面對被愚昧者捧起來的虛名,為了一種幻覺中的救世主的良好感覺而活著。在中國,他們的每一個動作,每一種聲音都將引起全社會的注視和傾聽;而在國外,他們形單影隻,再也得不到那麼多崇拜者的仰視,除了幾個關心中國問題的老外的熱情之外,沒有人肯向他們致敬。要承受這種寂寞需要的不再是社會的力量,而是個體的力量,是生命的才華、智慧和創造力的較量。因此,無論在中國多麼有名、有地位,一旦置身在陌生的世界中,就必須從最真實的個體存在開始與整個世界的對話。

正是基於此種理由,無論我多麼不遺餘力地贊美西方文化,多麼徹底地批判中國文化,我仍然是個「井底之蛙」,眼中只有巴掌大的藍天。在理論層次上,反省和批判中國的現實和傳統,並不需要太高的智慧,甚至不需要獨特的創造性思考。我對中國之反省所借助的理論武器都是已知的、現成的,無需我的新發現。那些被中國人視為高深的、新奇的道理,已經被西方的文化人們講得明明白白,而且已經過幾百年了,在西方已經變成了普及的常識,在思想創造上已經變得陳舊了,根本就用不著我的畫蛇添足。如果我能夠比較準確而深入地把握住這一參照系,就算不錯了。當我走進紐約的「大都會博物館」,我才醒悟到我曾經討論過的諸種問題對於高層次的精神創造來說,是多麼的無意義。我才意識到,在一個愚昧的、近似於沙漠的文化中封閉了太久的我,其思維是多麼浮淺,其生命力是多麼萎縮。長期在黑暗中不見天日的眼睛,已經很難盡快地適應於突然打開的天窗,突然見到的陽光。我無法一下子就成為敢於面對自己的真實處境的人,更不可能在短時期內與世界的高層次進行對話。但是我希望自己能夠放棄過去的所有虛名,從零開始,在一片未知的世界中進行嘗試性的探索。這種探索不僅需要人類的智慧已經創造出的大量現成的知識,更需要開拓未知的領域,需要憑純個體的智慧和做一個真實的人的勇氣。但願我能夠承受住新的痛苦,不為任何人,只是為了在絕境中踏出自己的路。即使失敗,但我相信這種失敗是真實的。它要勝過我曾經得到過的無數次虛假的成功。

二、

正因為我的民族主義立場和企圖借助於西方文化來改造中國,所以我對中國的批判是以對西方文化的絕對理想化為前提的。我忽略了或故意回避了西方文化的種種弱點,甚至是我已經感覺到、意識到的弱點。這樣,我就無法站在更高的層次上對西方文化進行批判性的反省,對整個人類的弱點給予抨擊。而只能向西方文化文明「獻媚」,以一種誇張的態度來美化西方文明,同時也美化我自身,彷彿西方文化不但是中國的救星,而且是全人類的終極歸宿。而我借助於這種虛幻的理想主義把自己打扮成救世主。儘管我一向討厭救世主,但那只是針對他人,一旦面對自己,很難不有意無意地進入自己討厭的角色中,飄飄然於救世主的大慈大悲、大宏大願之中。我知道,西方文明只能在現階段用於改造中國,但是在未來,它無法拯救人類。站在超越性的高度上看,西方文明的種種弱點正好顯露出人類本身的弱點。這使我想起莊子寫過的《秋水》。河水再大,之於海洋也是有限的;海洋再廣,之於宇宙也是渺小的;「天下之美盡歸於己有」只是一場夢而已。由此類推,中國之於西方是落後的,西方之於全人類也是有限的,人類之於宇宙更是渺小的。人類的目空一切的狂妄不僅表現在中國式的道德自足和阿?式的自滿之中,也表現在西方人的理性萬能、科學萬能的信念之中。不論現代西方人怎樣對自己的理性主義進行批判,也不論西方的知識精英對自身的殖民擴張和白種人優越感進行過多麼嚴酷的否定,西方人仍然對其他民族有一種根深蒂固的優越感。他們仍然自豪於自我批判的勇氣和真誠。西方人能夠坦然地接受自己對自己的批判,但是他們很難接受來自西方之外的批判。我作為一個在中國的專制制度下生活了30幾年的人,要想從人類命運和純個體的自我實現的高度來反省人類、反省自身,就必須同時展開不同層次上的兩種批判:

(一)以西方文化為參照來批判中國的文化和現實;

(二)以自我的、個體的創造性來批判西方文化。

這兩個層次的批判決不能相互代替,也不能相互交融。我可以指出西方文化的理性至上、科學至上和金錢至上導致了個體生命的消失和一切反抗性的商品化,批判技術一體化所形成的世界性經濟等級秩序,否定高消費的生活方式使人患有一種沒有懷疑衝動的富裕的疾病和逃避自由的怯懦,但是這一切批判決不能用於沒有科學意識的貧困的中國。因此,必須警惕的是:批判西方文化的參照系不能用於批判中國,更不能以中國文化為參照來批判西方文化。如果是前者,就將是對牛彈琴,無的放矢;如果是後者(以中國文化為參照批判西方),將導致整個人類文明的退化。有些西方的智者因不滿於自己的現實而轉向東方,企圖在東方文化中找到解決人類困境的鑰匙,這是盲目的、臆斷的妄想狂。東方文化連自身的地域性危機都無能為力,怎麼能夠解決整個人類所面臨的困境呢?

我認為,20世紀的人類所犯下的最大錯誤之一,就是企圖用人類已經創造出的現有的文明來擺脫困境。但是,無論是現有的東方經典還是現有的西方文化,都沒有使人類能夠走出困境的回天之力。西方文化的優勢至多能夠把落後的東方帶入西方化的生存方式之中,但是西方化的生存方式仍然是悲劇性的。到目前為止,人類還沒有能力創造出一種全新的文明,以解決人口爆炸、能源危機、生態不平衡、核武器日增、享樂至上、商品化等問題,更沒有一種文化能夠幫助人類一勞永逸地消除精神上的痛苦和人自身的局限。人類面對著自己所製造的、足以在一瞬間毀滅自己的殺人武器,其焦慮是無法擺脫的,這種焦慮作為當今人類的生存背景是任何人無法回避的。死亡的致命界限會把人類的一切努力變成徒勞。能夠正視這一殘酷的事實,同時又勇敢地踏入深淵的人已經是人類的極限了。自從人類被上帝逐出伊甸園之後,便一直處在無家可歸的流放之中,這個流放沒有盡頭,西方文化不是它的歸宿,而只是一段路程而已。更可悲的是,西方文化中的「原罪感」成分越來越淡泊,懺悔意識越來越蒼白,宗教的聖潔有時與搖滾樂一樣,成為一種享受而非痛苦的自省。自從耶蘇被釘在十字架上以後,人類中再也沒有殉難者了,人類失去了自己的良知。「原罪感」的逐漸消失,使人的生命變得輕飄飄的,這對於人類來說,無疑是又一次墜落,亞當和夏娃的墜落是人類無法輓回的,沒有「原罪感」的人怎麼能聽到上帝的聲音。從中世紀初期的上帝理性化到中世紀後期的上帝權力化,從近代的上帝徹底理性化到現、當代的上帝漸漸世俗化,人類文明墜落了,人類親手殺死了自己心中的神聖價值。

因而,當我借助於西方文化對中國文化進行了批判性的反省之後,突然手足無措,陷入一種進退維谷的尷尬處境之中。我猛烈醒悟:我是在用已經陳舊的武器去批判另一種更為陳舊的文化,以一個半殘廢的自豪去嘲笑一個全癱的人。當我真正地置身於開放的世界之中時,驀然發現──我不是理論家、更不是名人,而是一個必須從零開始的凡人。在中國,愚昧的背景襯托出我的智慧,先天痴呆突現出我的半吊子健康;在西方,愚昧的背景一旦消失,我便不再是智慧;痴呆兒的烘托一旦倒塌,我便成了通身有病的人。而且我的周圍也站滿了各種病人。在中國,我為一個摻入了百分之九十的水分的虛名而活著;在西方,我才第一次面對真實的生命呈現和殘酷的人生抉擇。當一個人從虛幻的高峰一下子墜入真實的深淵,才發現自己始終沒有登上過高峰,而是一直在深淵中掙扎。這種大夢初醒之後無路可走的絕望,曾使我猶豫、動搖,並怯懦地嚮往那個我了如指掌的土地。如果不是「大都會博物館」,我真的就要重新與愚昧為伍了。

我的妻子曾在一封信中寫到:「曉波,表面上看,你是這個社會出名的逆子,但在實質上,你與這個社會有一種深層的認同,這個社會能夠以一種反對你的態度容納你、寬恕你、吹捧你,甚至慫恿你,你是這個社會的一種反面的點綴和裝飾。而我呢?一個默默無聞的人,我不屑於向這個社會要求什麼,甚至連罵的方式也不想,我與這個社會的一切才是格格不入,連你都無法理解我的冷漠,你都不能容納我。」這段話,我曾經毫無感覺,現在回想起來真是一針見血。我感謝她。她不僅是我的妻,更是我的最尖刻的批評者。在她的種種批評面前,我無地自容。

我再也沒有退路,要麼跳過懸崖,要麼粉身碎骨。想自由,就必須身臨絕境。

最後,我想就某些西方人對中國的獻媚說幾句不好聽的話。一些西方人對中國文化感興趣,贊美之情溢於言表,我以為是基於以下幾種心理:

(一)僅僅是出於純個人的性格、氣質、愛好和價值選擇而喜歡中國文化,在中國文化中找到了某種精神寄託和心靈安慰,這是一種真實的人生態度,無可厚非。可惜的是,這樣的只對自己負責的西方人太少了,極而言之,這樣的人太少了。

(二)出於對西方文化的不滿而轉向中國,企圖在中國文化中尋找改造西方文化的武器。因此,他們把一種落後的、封閉的文化思想作為參照系,用西方人的智慧來解釋中國文化。這決不是西方人的東方化,仍然是西方本位論。我認為,每一種文化都是排他的,除非有超越性的天才誕生,否則的話,無人能跳出自身文化的牢籠。西方人對中國文化的理想化,作為個人的選擇可以,但是作為解決人類困境的方法和武器,則只能使人類倒退。比把人類的未來希望寄託在西方文化之中更為荒謬。

(三)出於一種西方人的優越感,以俯視的貴族姿態對待中國文化。他們對中國文化的肯定,就象一個成年人誇獎一個孩子說話象大人,象一個高高在上的主人贊美奴隸的忠誠一樣,是一種恩賜加輕蔑的態度。我此次出國,經常聽到這樣的誇獎:「我第一次聽到一個中國人這樣說」或者「一個中國人能對西方哲學如此瞭解」或者「中國怎麼能出你這樣的逆子。」這些誇獎的潛台詞是:中國人一向是劣等的。每次聽到這種贊美,我就感到自己不是出國,而是被人放在皮箱中,拎上飛機,作為一件新奇的物品帶到異域,他們想你放在哪兒,你就必須在哪兒。由此可見,儘管有幾百年的民主化、平等化,但是人類難以根除的主人欲並沒有消失,一遇契機,立刻復活。當然,這樣的西方人大都是那些極為功利化的所謂漢學家。

(四)作為一個觀光客,出於對陌生事物的驚奇而贊美中國文化。那些已經享受過並且永遠不會放棄享受現代文明的西方人,需要一種調節,換一換味口。而中國在數十年封閉之後突然開放,肯定會為他們提供最好的觀光地。中國的愚昧、落後甚至原始是一種完全不同於西方文明的文化,能夠激起觀光客的好奇心、神秘感。他們贊美中國文化完全是出於自身好奇心的滿足。如果這些觀光客自己享受之後,便不再議論大是大非,也沒有什麼不好。關鍵在於,有些觀光客在自我享受過後,把這種享受提升為一種人類性的文化選擇,其荒謬性就太過分了。而且,他們只觀光,而決不會留下來。這樣,他們就更沒有理由告訴中國人:「你們的文明是第一流的,是人類的未來。」這種由觀光客到救世主的轉化,不只是荒謬,而且是殘酷。這使我想起古羅馬時時期的奴隸角鬥。坐在看台上的貴族們決不會親自嘗試角鬥,但卻狂熱地喜歡看角鬥。野蠻的、嗜血的場面確實富有新奇感和刺激性,可以成為一種享受。但是,對於角鬥著的奴隸們來說,這喝采聲太殘酷了。坐在飛機上欣賞原始的老牛耕地,確有田園風味,但是觀賞者決不應該在自己享受的同時,告訴被觀覺者永遠刀耕火種,永遠表演下去。看一幅原始味十足的繪畫可以如此,但是如果把活生生的生活和人當作審美對象,並要求審美對象的永恆性,這就太不公平、太殘酷了。用他人的痛苦來滿足自己的享受,這是人類的醜陋之最。作為一個中國人,我太清楚中國不會成為人類21世紀的希望。在一個已經分配得井井有條的等級世界中,在能源如此匱乏的地球上,十幾億人口的中國怎麼能夠成為21世紀的希望。即便中國的自我改造在短期內獲得成功,中國也無法達至美國和日本的經濟水平,地球已經承擔不起再出現一個超級大國的重負了。因而,我不企望藉助於任何民族的繁榮來提升自己,也不會把希望寄託在任何一個群體之中,更不指望社會的進步能夠解決我個人的前途;我只能靠自己,靠個體的奮鬥去與這個世界抗衡。

(五)還有極少數西方人,是從純學術的角度去看中國的,他們比較客觀、清醒,在一定的距離這外研究中國。中國的好壞與他們的切身利益無關,但是他們對中國的看法更真實,更具有理論價值。中國人最應該傾聽的是他們的聲音。

寫完這個後記,我感到很疲倦。

最後,我感謝夏威夷大學亞洲太平洋學院中國研究中心為我提供了寫作此書的時間和環境。感謝我的朋友Jon Solomon與我討論這本書以及他為此書的出版所付出的精力。

(1989年3月於紐約)