The Best China

In the first installment of The Best China, a China Heritage series focussed on Hong Kong launched on 1 July 2017, we introduced readers to recent commentaries written by the veteran journalist Lee Yee 李怡 (李秉堯).

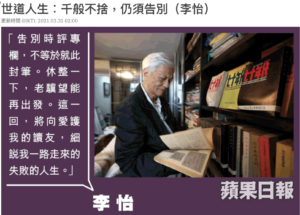

Founding editor of The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊 (later renamed The Nineties Monthly) Lee Yee has been a prominent commentator on Chinese, Hong Kong and Taiwan politics, as well as the global scene, for over fifty years. His position has gone from that of being a sympathetic interlocutor with the People’s Republic during the 1970s to that of outspoken rebel and man of conscience from the early 1980s. For decades, Lee has analysed Hong Kong politics and society with a clarity of vision, and in a clarion voice, rare among the territory’s writers. The essays by Lee Yee that we translated in China Heritage are from ‘Ways of the World’ 世道人生, the regular column Lee wrote for Jimmy Lai’s Apple Daily 蘋果日報.

On 31 March 2021, Lee Yee told his readers that the changed circumstances in Hong Kong, and his advanced age, had led him to decide to cease publication of ‘Ways of the World’. From mid April, Lee began publishing a new series of interconnected essays under the title Reminiscences of One of the Defeated 失敗者回憶錄.

In mid April, Margaret Ng 吳靄儀, an old friend of Lee Yee’s, a former Hong Kong lawmaker, barrister and veteran Civic Party member, was one of the nine democrats convicted of organising and participating in a peaceful protest on 18 August 2019. She was given a twelve-month sentence, which was suspended for twenty-four months.

The mitigation plea that Ng addressed to the court has been widely circulated internationally. Sebastian Veg suggested that China Heritage should publish a translation of Lee Yee’s farewell essay, and we do so with a heavy heart.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

24 April 2021

***

Related Material:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The Road Not Taken by Margaret Ng 吳靄儀, China Heritage, 24 April 2020

- Margaret Ng 吳靄儀, ‘Hong Kong 攬炒 — Burning Down the House’, China Heritage, 1 May 2020

- Margaret Ng’s Mitigation Plea, Hong Kong Free Press, 16 April 2021

Selected Essays by Lee Yee in China Heritage:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Endgame Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 5 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Young Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 16 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Hong Kong Goes Grey for a Day’, China Heritage, 20 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘This is Who We Are — We Are Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 22 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Living and Learning in Hong Kong 2019’, China Heritage, 29 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984’, China Heritage, 31 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Restoring Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’, China Heritage, 6 August 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The Mission of Our Times in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 28 August 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Superfluous Words’, China Heritage, 20 November 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘The End of Hong Kong’s Third Way’, China Heritage, 22 April 2020

- Lee Yee 李怡 & The Editor, ‘Jimmy Lai, the Twilight of Freedom & the Dawn of “Legalistic-Fascist-Stalinism” 法日斯 in Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 12 August 2020

***

On Reaching Eighty Five

On 14 April 2021, Lee Yee celebrated his eighty-fifth birthday. He marked the occasion by quoting passages from some of his old essays, including one published on the occasion of his eightieth birthday in April 2019. In it he said that the birthday gift that had the greatest impact on his life was The Complete Works of Lu Xun, which his father had given to him on his sixteenth birthday. He then quoted the following passage from ‘Random Thoughts: Thirty Eight’, an essay that Lu Xun published in 1918:

The Chinese have always tended towards self-importance, sadly, it has manifested as a kind of ‘collective patriotic afflatus’ rather than being a sense of the individual’s self-worth. This is why in the wake of the country’s failure to compete culturally with outsiders, it has proved itself to be unequal to the task of being able to get a grip and make noteworthy advances.

中國人向來有點自大。——只可惜沒有「個人的自大」,都是「合群的愛國的自大」。這便是文化競爭失敗之後,不能再見振拔改進的原因。

A true sense of self-worth is a form of individualism that is nothing less than a unilateral declaration of war on the common crowd. Apart from those with what the psychologists call delusions of grandeur, the kind of self-importance I’m speaking about here is the reflection of a particular kind of genius. —— According to physicians like Max Simon Nordau, one symptom is a measure of sublime arrogance. Individuals thus possessed are convinced that their ideas are superior to yet misunderstood by the common herd. That’s why they display a contempt for the world and its ways. Over time they become habituated to such a disposition and may well end up being regarded as ‘Enemies of the People’. The truth of the matter, however, is that they are the source of all truly innovative ideas; all reforms, be they in the political or religious realm, originate with them. That’s why a nation that can boast many such self-important individualists is truly fortunate.

「個人的自大」,就是獨異,是對庸眾宣戰。除精神病學上的誇大狂外,這種自大的人,大抵有幾分天才,——照Nordau等說,也可說就是幾分狂氣。他們必定自己覺得思想見識高出庸眾之上,又為庸眾所不懂,所以憤世疾俗,漸漸變成厭世家,或「國民之敵」。但一切新思想,多從他們出來,政治上宗教上道德上的改革,也從他們發端。所以多有這「個人的自大」的國民,真是多福氣!多幸運!

Conversely, the ‘self-importance of the crowd’, as well as the ‘afflatus of patriots’ reflects a demeanor that demands compliance and outlaws difference. It is one that declares war on the small number of uniquely gifted individuals in their midst. —— & it’s something that takes precedence over declaring war on the civilisations of other nations. They lack any talent worthy of boasting about to others, and so they use this country as a shadow, a feint: they raise a great hue and cry about the so-called ingrained habits and system of this place, heaping them with praise. Since their ‘national essence’ is so wondrous they naturally bask in its reflected glory! When they encounter an attack they feel no need to take up cudgels for they conceal their vulgar gesture in the shadow; they have countless stratagems at their disposal and the wiles of the mob which, under the guise of distracting clamour, they lay claim to a pyrrhic victory.

Victory is ours, because I am part of the crowd. Even if we are defeated, since there are so many of us, I won’t necessarily lose out myself and, when a mob creates one of those inevitable disturbances, that’s exactly how everyone thinks. It’s a collective and individual mindset. It may, for all intents and purposes, appear as if they are launching a furious action, but they are really cowards. As for what comes of all the hubbub — a restoration of the past, a newly discovered adulation of autocrats, support for the stricken empire and a desire to obliterate foreigners, and so on and so forth — we’ve all seen just where that leads. That’s why a country that boasts about its crowds of ‘patriotic masses’ is but a pitiable place and a most unfortunate nation!

「合群的自大」,「愛國的自大」,是黨同伐異,是對少數的天才宣戰;——至於對別國文明宣戰,卻尚在其次。他們自己毫無特別才能,可以誇示於人,所以把這國拿來做個影子;他們把國裡的習慣制度抬得很高,讚美的了不得;他們的國粹,既然這樣有榮光,他們自然也有榮光了!倘若遇見攻擊,他們也不必自去應戰,因為這種蹲在影子裡張目搖舌的人,數目極多,只須用Mob的長技,一陣亂噪,便可制勝。勝了,我是一群中的人,自然也勝了;若敗了時,一群中有許多人,未必是我受虧:大凡聚眾滋事時,多具這種心理,也就是他們的心理。他們舉動,看似猛烈,其實卻很卑怯。至於所生結果,則復古,尊王,扶清滅洋等等,已領教得多了。所以多有這「合群的愛國的自大」的國民,真是可哀,真是不幸!」

— 魯迅,《隨感錄三十八》

Are these the words of some contemporary writer? No: they were written over a century ago, by Lu Xun on 15 November 1918, and published under the title ‘Random Thoughts: Thirty Five’, one of the essays collected in the volume Hot Air.

I quote this passage here to illustrate the fact that a commentary by Lu Xun like this is as relevant today as it was a century ago It also illustrates why the essays and fiction of a writer who was praised by Mao Zedong in Yan’an [in the early 1940s] are now gradually being excised from high-school textbooks in China. The roots of Chinese autocracy past and present grow out of what Lu Xun called here ‘collective patriotic afflatus’. It’s a form of hubris that the power-holders manipulate in order to maintain the support of the supine majority. Thus it was before and so it continues to be today.

這是現代人寫的文章嗎?不。這是100年前,1918年11月15日魯迅發表在《新青年》的文章〈隨感錄三十八〉,後收入他的文集《熱風》中。

摘錄這小段文字,就明白為甚麼魯迅的時論文章在今天讀來都不覺過時,也明白為甚麼這位在延安時期備受毛澤東稱道的作家,他的小說、雜文近年在中共國的教科書中不斷被剔除了。中國歷代的專制政權,都是植根於這種「合群的愛國的自大」中,也利用這種「自大」去凝聚⺠眾的奴性,經久不息,延綿至今。

***

The Sweet Sorrow of Parting

千般不捨,仍須告別

Lee Yee 李怡

translated & annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

I am hereby bidding farewell to ‘Ways of the World’, the series of essays that I started writing for Apple Daily in 2016. While I am loath to take my leave of all of the readers who have supported my column over the years, I fear that the time has come for me to bid you all adieu. Given the unpredictable state of human affairs there’s no telling whether we might be able to meet again in this way. The undeniable reality for a person in their eighties like me is that it’s doubtful that many new opportunities to write commentaries on current affairs will readily present themselves.

這是「世道人生」專欄的告別篇。懷着對愛護這專欄讀友的千般不捨,仍須告別。是否後會有期,儘管世事難料,但耄耋之年,寫時評的機會怕不多了。

Given that we are living at a time in which all kinds of conspiracy theories flourish, I feel I must make it absolutely clear that last year when I reduced the number of commentaries I wrote each week from five to three, I was doing so entirely of my own volition. Apple Daily didn’t pressure me to do so nor, for that matter, was it a response to the slings and arrows of those who wished me ill. After all, in a writing career that has spanned some sixty years, I’ve never been in want of critics. Having said that, I should add that, nonetheless, I am now confronted by another, undeniable and implacable pressure. With the imposition of the Hong Kong National Security Law on 1 July 2020, political commentators like me can no longer expect to enjoy the protection of the law. This has been truly an unprecedented development.

在陰謀論盛行下,首先要澄清的,從每周五篇到三篇到告別,都是出自我自己的意向,不是《蘋果》的意思,也不是因為受到明槍暗箭攻擊。寫作60多年,這樣的事還遇得少嗎?但香 港國安法的實施,使論政失去了法律保護,卻是我寫作60多年來沒有遇到過的,是實實在在的壓力。

In my previous essay [‘Why I Love Martha Gellhorn’ 愛上何桂藍, Apple Daily, 29 March 2021], I observed that this is an age in which ‘everyone can say everything about some things, while other matters have become completely unspeakable’. We are living with absurdity; we have witnessed a Hong Kong that always enjoyed the benefits of the rule of law and rational civic life disappear before our very eyes. The nature and meaning of what has been happening is obvious to all, and everyone is equally a critic of the realities of our situation, no matter how minuscule.

[As Lee Yee wrote in that earlier essay:

‘You don’t need to be a specialist or a political commentator to be able to analyse what’s really going on. Everyone can tell you just how farcical things have become; everyone knows that even the women and men in power don’t believe the grandiose things they say.’

人人可以講,意思是不需要專家,不需要評論家,任何人都可以告訴你社會多麼荒謬,都懂得批評那些掌權的大人先生女士們一本正經地講些自己都不相信的道理。]

Given this situation, what good is a commentator like me?

The very fabric of our society has been rent; pro-Beijing and pro-Hong Kong camps remain at loggerheads. Meanwhile, in the United States, conservatives and members of the liberal elite are as divided as ever. The political commentariat and the witterings of those known as ‘key opinion leaders’ continue to flourish and they circulate entirely independently of one another, garnering droves of partisan likes and followers in the process. Warring camps endlessly find fault with each other and reject things despite being presented with incontrovertible evidence to the contrary. Rational exchange between differing parties is well nigh impossible and all attempts at persuasion have become futile.

Even when I went to considerable lengths to back up arguments with historical facts in the essays I wrote for ‘Ways of the World’ I did, at best, only manage to bolster the views of people who already agree with me and was powerless to influence the intransigent in any way. These days, everyone has an opinion about just about everything, and they are unstinting with their criticism.

前日拙文提到我們所處的時代特點,就是「人人可以講,又人人不可以講」。世界太荒謬,法治和理性管治在香港光速淪喪,任何人都看得到這變化,多麼小的事情,也人人懂得批評,這樣,還要評論家來做甚麼? 社會撕裂下,香港黃藍對立,美國保守與左膠對立,論政文章和KOL談話各自在同溫層流動,認同的紛紛認同,不認同的紛紛挑剔,明擺的事實也會被否定,理性的交流與說服變得沒有意義。近年我發現,我查找歷史實例,提出理論根據,也只是加強同溫層人們的已有觀念而已,並不能改變不同意見者的固執。而絕大部份的現象,人人都可以講一通,都忍不住要批評。

Then there’s all the things that people simply can’t talk about anymore. Here in Hong Kong people are afraid of a legal system that they know will no long protect basic civic rights. America, along with the West as a whole, is now regularly decried as being ‘politically incorrect’. What in the past would be thought of as being a statement of the obvious is now regarded as positively daring here in Hong Kong, while in America it is decried as being ‘discriminatory’.

[In the essay ‘Why I Love Martha Gellhorn’ Lee Yee remarked that:

‘The reality about “those things that can no longer be said” affects both what appears in the mainstream media as well as on social media. The vagaries of the National Security Law can be deployed and the proliferation of red lines that cannot be crossed means that no one can be sure how things might be dealt with either by the police or by the law courts. The taboos are not limited to the print media for even the arts are now embroiled, as has been the case with the contemporary art museum M+ which has been accused of “insulting national dignity”. And the official pro-Beijing media has decried the [award-winning] documentary film “Inside the Red Brick Wall” for “disseminating sentiments invidious to the state”, leading to the film being banned. ….

‘Then there are all the words and expressions that have now been rendered unsayable, like “Restore Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Time” and “Bring Back the Glory of Hong Kong”. Even the rallying cry people use at sports events like “Go For It, Hong Kong!” is verboten. If, over time, Hong Kong is reduced to the level of the Mainland then such things as freedom, democracy, the rule of law, the Communist Party, Winnie the Pooh and Cuicui [both lampooning references to Xi Jinping] will also become taboo, and new homophones and strange expressions will crop up all the time, none of which most Hong Kong people can understand. Banning what can be said is a wilful form of self-delusion; after all, not only will the things that people really want to say still exist, they will surge mightily in people’s hearts and minds regardless of all attempts to suppress them. …’

但現實是「人人不可以講」,是指不能在媒體上講,哪怕只是社交媒體。國安法太多任憑解釋的模糊地帶,執法和司法太難以預期,越來越多看不見的紅線。禁忌從文字談話延伸到藝術,M+藝術館被指「侮辱國家尊嚴」、《理大圍城》紀錄片被官媒指「散播仇視國家情緒」,無法上映。…

許多語詞都不能說,「光復香港,時代革命」「願榮光歸於香港」不能說,連「香港加油」也不能說。若向中國大陸看齊,連自由、民主、法治、共產黨、小熊維尼、翠翠等都是禁忌,許多香港人或看不懂的諧音、怪字頻頻出現。「不可以說」只是掩耳盜鈴,自欺欺人,而「人人要說」的話不僅存在,而且會因禁言而在人們心中更澎拜。…

— 世道人生:愛上何桂藍, 29 March 2021]

Over the decades I have always done my level best to write the truth, to express my views clearly and in terms of what could be appreciated as a common sense approach. Now, however, what I have to say can no longer be said. In fact, I recently re-read the four essays by the philosopher Hsü Fu-kuan on the topic of ‘the greatness of normality’ [which he wrote some forty years ago shortly before his death]. I appreciate more than ever his view that when societies oppose tradition in their quest for the ‘extraordinary’ they invariably fall prey to ‘abnormality’. [This is a play on the words 正常,非常,反常.]

[For Hsü’s essays, see here]

但「又人人不可以講」,香港是怕觸犯了已經不再是保護市⺠權利的法律,美國和⻄方則是動輒被指為「政治不正確」,過去只是常識的一句話,在香港變成「最勇敢」,在美國被指為「歧視」。我寫了幾十年的真話、大白話、常識話,變成「人人不可以講」。最近重讀徐復觀在40年前寫的幾篇《正常即偉大》,深深體念到人類社會在反傳統中,由於追求「非常」而必然跌入「反常」的道理。

Apart from the things that are allowed to be said, the nature of the authoritarianism that I’ve been writing about for all of these decades is the same as it ever was, and what I have to say about it all pretty much amounts to the same thing. To keep on writing in this vein is boring, even for me. As for those things that are ‘no longer allowed to be said’, whatever one writes or says in Hong Kong now can suddenly end up with you falling foul of the law, or it may well lead your being ‘ensnared in the net of words’.

「人人可以講」之外,作為論政對象的強權數十年還是老樣子,提出議論的觀點來來去去都是這些,我再寫連自己都覺得無意義;而「人人不可以講」,白紙黑字寫出來或公開出來,徒然罹法網,又或者罹文網。

Another equally cogent reason for my decision to stop writing commentaries on current affairs is that I am, after all, eighty-five years old. In the past, I could dash off a piece in one go, but these days even searching through reference materials has become a struggle; moreover, I’m constantly worried that I’ll end up repeating what I’ve said before. The truth of the matter is that neither my mind nor my body are up to it any more.

It’s three years since I announced that I was going to cut back on the time I spent writing about current affairs so that I could focus on writing my memoirs. But that plan was frustrated by the unfolding situation in Hong Kong, one which inspired me to write about the here and now. That, in turn, forced me to reflect on and reconsider my previous stance regarding a number of things. [See, for example, Lee Yee, ‘Restoring Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’, China Heritage, 6 August 2019.]

During 2020, the pandemic and the presidential election in America became a new focus of my attention and both had an impact on my writing, right up to the point that a value system [that underpinned free speech] that I had always sought to defend was completely undone. The media freedom that I had so valued in America proved to be unable to withstand the depredations of elite liberal currents of thought [that advocate a ‘cancel culture’] and corporate politics. Although I had devoted myself to supporting the ‘conservatism of the normal’, left-leaning simpletons disparaged my efforts, despite what I was really trying to say.

My credo has always been to engage actively with contemporary life even while maintaining an overall pessimistic outlook on how things would turn out. Now my pessimism has soured into hopelessness and I am confronted by the fact that the concept of freedom of speech that I have supported and pursued throughout my writing career has been undone by brute shamelessness.

You see, there is a breed of self-appointed leftist that rejects the idea that we should stand up for the rights of those with whom we disagree. Daresay, people of that ilk will be delighted to learn of the demise of my column ‘Ways of the World’.

另一個原因當然就是已屆85高齡,很老了。以前寫作常常一揮而就,現在翻查資料就要老半天,加上不想重複自己講過的觀點,因而精神體力都倍感不足。前年3月,已表示過決定在這個專欄減少寫時評,較多寫過往的人生,但接着就被社會發生的事情牽動着關注,不能不寫自己對當前時世的感受和評論,也無時無刻不因時局變化而產生對自己既有觀念的審視。

去年疫情和美國大選,我仍然無法不受感情牽引而繼續關注時局,直到我努力要維護的價值系統徹底崩壞,我崇信的美國新聞自由,竟在左膠思潮和錢權侵擾下不堪一擊。我努力想維護的保守主義正常社會價值,被不顧文意的左膠大潑髒水。悲觀而積極,是我的人生信條。但悲觀到一個絕望點,就不能不承認一生追尋的言論自由,被無恥打敗了。左膠學棍公開宣揚不支持「維護不同意見的表達權利」,他看到我這專欄的告別,應該很高興吧。

Bidding farewell to this column does not, however, mean that I am giving up writing altogether. After a short period of adjustment, I plan to sally forth again. I will compose a series of essays in which I will present to my devoted readers an account of what has proven to be a lifetime of failure.

告別時評專欄,不等於就此封筆。休整一下,老驥望能再出發。這一回,將向愛護我的讀友,細說我一路走來的失敗的人生。

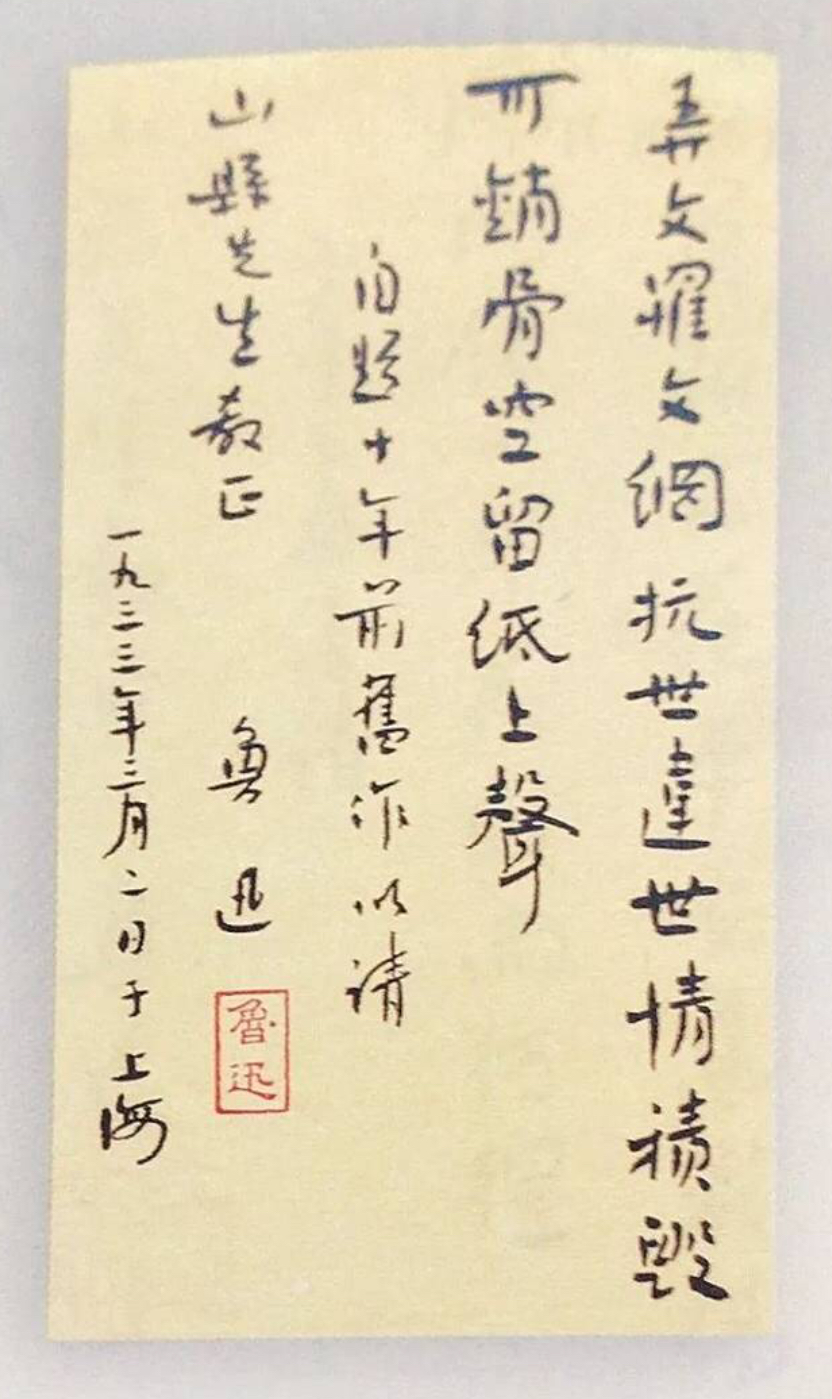

But here I will conclude by drawing once more on Lu Xun who provides an apt epitaph for this, the final essay in ‘Ways of the World’:

Through my literary efforts I became ensnared in the net of words;

Defying the commonplace I offended prevailing sentiment.

Their slanders might threaten to dissolve the marrow of my being;

I voiced my thoughts regardless, albeit as a vainglorious gesture.引魯迅詩作為專欄告別語:

弄文罹文網,抗世違世情。

積毀可銷骨,空留紙上聲。

***

Source:

- 李怡,’千般不捨,仍須告別’,《蘋果日報》,2021年3月31日

***