Dog Days (V)

As students struggle with the sounds and tones of Standard Chinese 普通話/ 國語, and learn about the linguistic variations of tone and pronunciation found in regional languages, they are often introduced to the work of Yuen Ren Chao (趙元任, 1892-1982), a noted linguist and grammarian.

‘An Account of Mr Shi Eating Lions’ (Shī Shì shí shī shǐ 施氏食獅史), which was composed in the mode of A New Account of Tales of the World 世說新語, has confounded, and entertained, generations of beginners. In writing this short anecdote Chao, a connoisseur of puns, played on the sound ‘shi’ while addressing the theme of ‘eating lions’ shí shī 食獅:

Shī Shì shí shī shǐ

Shíshì shīshì Shī Shì,

shì shī, shì shí shí shī.

Shì shíshí shì shì shì shī.

Shí shí, shì shí shī shì shì.

Shì shí, shì Shī Shì shì shì.

Shì shì shì shí shī, shì shǐ shì,

shǐ shì shí shī shìshì.

Shì shí shì shí shī shī, shì shíshì.

Shíshì shī, Shì shǐ shì shì shíshì.

Shíshì shì, Shì shǐ shì shí shì shí shī shī.

Shí shí, shǐ shí shì shí shī shī,

shí shí shí shī shī.

Shì shì shì shì.

《施氏食獅史》

石室詩士施氏,

嗜獅,誓食十獅。

氏時時適市視獅。

十時,適十獅適市。

是時,適施氏適市。

氏視是十獅,恃矢勢,

使是十獅逝世。

氏拾是十獅屍,適石室。

石室濕,氏使侍拭石室。

石室拭,氏始試食是十獅屍。

食時,始識是十獅屍,

實十石獅屍。

試釋是事。

An Account of Mr Shi Eating Lions

There was a poet by the name of Shi in a stone study. He had a liking for lions and resolved to eat ten of them. He often went to the market on the look out for lions. At ten o’clock one day, ten lions had just arrived at the market. At that time, Shi himself also arrived at the market. He saw the ten lions and, using his trusty arrows, he made all ten lions die. He gathered up the corpses of the ten lions and they reached the stone study. But the stone study was damp and Shi had his servants wipe it down. After the stone den was wiped, Shi set to eating the corpses of the ten lions. As he did so, he realised that the ten lions were in fact the corpses of ten stone lions. Try to explain this matter.

Chao’s sibilant tour de force is something of a minor linguistic classic. It was also used in arguments mounted against abandoning traditional orthography — that is, the Chinese character 漢字 — in favour of a romanised spelling system. Despite having been written in non-colloquial literary Chinese, ‘An Account of Mr Shi Eating Lions’ was supposed to demonstrate how romanisation of the language could lead to misunderstandings and mutual incomprehension.

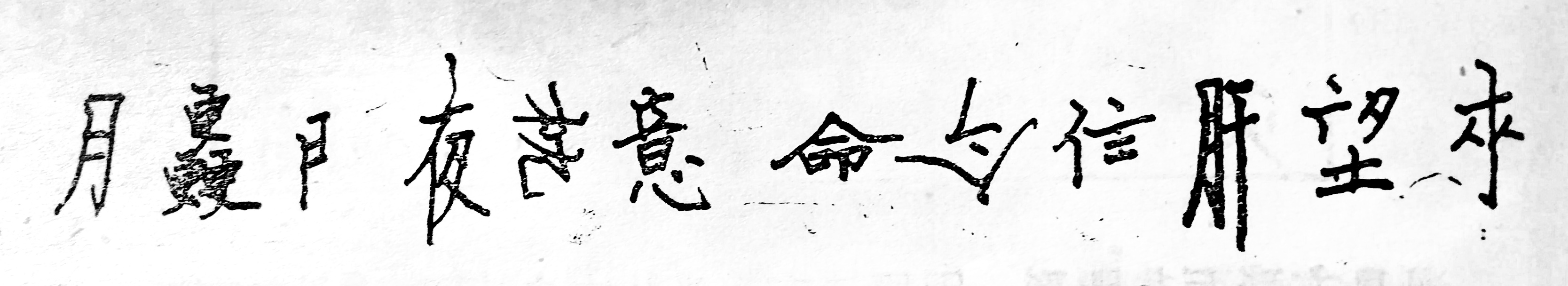

Chao’s composition belongs to a long tradition of word-play and literary games. Another example, one in a rather different vein, will have to suffice here. It is a well-known ‘rebus poem’ (神智體詩) by You Mengniang 尤孟娘:

The poem reads as follows:

斜月三更門半開,夜長橫枕意心歪。

短命到今無口信,肝長望斷無人來。

***

Pairs of stone lion-dogs are used as an architectural feature outside temples, burial places, princely mansions and even private residences. A major symbol of transvalued Chinoiserie today, they feature as entrance decorations cum-guardians at banks, public buildings and Chinese embassies.

Lions are thought to have been introduced into China during the Han dynasty; stylistic stone carvings of the creatures appeared during the ascendance of Buddhism: after his enlightenment Siddhārtha Gautama, that is, ‘Buddha’, was also known as Shakyasimha 釋迦獅子, ‘Lion of the Shakya’. (Another common appellation is Shakyamuni, ‘Sage of the Shakya clan’, 釋迦牟尼 or 釋尊 in Chinese.) The Buddha, and various bodhisattva, are often depicted seated on lion thrones.

Over time the sculptural form of the lion was further sinicised and the creature is said to have acquired some features of the dog. In Japanese temples stone guardian lions, which were thought to have been introduced from China via Korea, are known as ‘Korean dogs’ 狛犬 or 高麗犬. During later Chinese dynasties the creatures were also positioned to flank entrances to palaces, halls and mansions. The male lion-dog always on the left holds a woven ball under a claw, while on the right the female has a cub under paw. Both stone lions 石獅 and bronze lions 銅獅 are popular and, as we will see below, inflatable lions-dogs have also made an appearance.

Internationally, in particular in the United States of America, these beasts are also referred to as ‘Fu Dogs’, ‘Foo Dogs’, ‘Fu Lions’, ‘Lion Dogs’ and even ‘Peking Foo Dogs’. It is thought that the term ‘Foo Dog’ was inspired by either the word fó 佛, Buddha, or fú 福, ‘good fortune’, ‘prosperity’, as both were associated with the guardian lions of temples. Then again, the appearance of Chinese dog breeds such as the Chow 鬆獅犬 (literally, ‘puffy-lion dog’) or the Shih Tzu 獅子狗 (‘lion dog’, also known as 西施犬) may have contributed to the origins of the Foo Dog. Regardless, we include Foo Dogs here in our introduction to a gallery of photographs by Lois Conner, our long-term collaborator, to mark the Year of the Dog.

***

We further preface this photographic gallery with a quotation from ‘A Spectre Prowls Our Land’ 一個幽靈在中國大地遊蕩, a poem written in 1980 by Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒. We have frequently quoted Sun before; one stanza of his poem in particular resonates with the Year of Dog:

China, like a huge dragon, gobbles all in its path,

Like a huge vat, dyes all the same colour.

Have you not seen the lions of Africa,

the lions of America,

Fierce kings of the jungle?

When they enter our dragon’s lair

they become mere guard-gods,

rings through their pug nostrils,

standing guard at yamen and palace gate…

中國呵,像一條巨龍能吞噬一切

它能同化一切,

就象一個巨大的染缸

你不見非洲、

美洲的獅子麼?

它原本粗獷、勇猛,

是大森林的獸中之王

一旦到了龍的故土,

竟被銅環鎖住鼻孔像看家狗,

守侯在衙門、

宮殿的大門兩旁

— Sun Jingxuan, Chengdu, October 1980

trans. John Minford with Pang Bingjun 龎秉鈞

(from Geremie Barmé & John Minford, eds,

Seeds of Fire, 1986, pp.122, 128)

Note: The ‘huge vat’ is inspired by the writer Lu Xun’s observations concerning China’s ancient culture being like a ‘vat of black dye’ 染缸 that taints everything. In a speech delivered in 1981, later published under the title The Ugly Chinaman 醜陋的中國人 and translated by Don Cohn, the Taiwan-based essayist Bo Yang 柏楊 (郭衣洞, 1920-2008) extended Lu Xun’s metaphor and lambasted the ‘soy-sauce-vat culture’ 醬缸文化 that corrupts the country’s politics and social mores.

***

This is the fifth installment in the ‘Dog Days’ series, an addition to New Sinology Jottings.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

Twenty-ninth Day of the

First Month of 2018

Wuxu Year of the Dog

戊戌狗年正月廿九

16 March 2018

Dog Days 2018

- The Editor, Mondo Cane, The 2018 Year of the Dog 戊戌狗年, China Heritage, 16 February 2018

- Don J. Cohn, A Pride of Pekingese — Dog Days (I), China Heritage, 18 February 2018

- Pu Songling, The Dog Lover — Dog Days (II), China Heritage, 24 February 2018

- Lee Yee and The Editor, The Real Man of the Year of the Dog — Dog Days (III), China Heritage, 2 March 2018

- The Editor, Objecting — Dog Days (IV), China Heritage, 5 March 2018

A Gallery of Lions for

The Year of the Dog

Lois Conner

Lois Conner and Geremie R. Barmé collaborations

- The Garden of Perfect Brightness, a life in ruins, 1996

- China: The Photographs of Lois Conner, New York: Callaway, 2000 (essay)

- Lois Conner exhibition, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, 2001, catalogue

- Twirling the Lotus: Photographs from Tibet and China, 2007 (essay)

- Life in a Box, 2010 (essay)

- Beijing Building, London: Rossi & Rossi, 2011 (essay)

- Works by Lois Conner featured in the Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship Office, later the offices and corridor occupied by the nascent Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW), Coombs Building, Australian National University, 2006-2014

- China Heritage Quarterly: annual masthead images, 2009-2012

- China Heritage Quarterly: photographic essays in issues focussed on The Garden of Perfect Brightness; Beijing; Shanghai; and, West Lake

- Lois Conner’s review of Felice Beato — a Photographer on the Eastern Road for China Heritage Quarterly

- China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse, cover image

- The China Story Gallery, 2012-2014

- Beijing, contemporary and imperial, Princeton Architectural Press, 2014

- ‘Beijing, an unfolding landscape’, Inaugural CIW Exhibition, exhibition and catalogue, May 2014

- Works by Lois Conner in the Australian Centre on China in the World, 2014-2015

- A painting by Zhang Peili 張培力 donated to the Australian Centre on China in the World on 26 August 2016 by Lois Conner to celebrate the creation of the Centre

- China Heritage, masthead, 2016

- A New York Eye on The Rapa, China Heritage

- China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking, masthead, 2017

- 顛倒 Downside Up, exhibition title and essay, March 2017

- Exhibition at le Quartier Français, Featherston Booktown, South Wairarapa, 13-14 May 2017

- The Affinities of Art 藝海因緣 — to celebrate Lois Conner and Zhang Peili 張培力, China Heritage, 26 August 2017

- Lotus Leaves, poems by P.K. Leung, photographs by Lois Conner, launched at the Wairarapa Academy Symposium, February 2018

- New Sinology Reader, masthead, 2018