Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Appendix XIX

臺上臺下

In ‘China’s Political Silly Season’ we quoted an anonymous petition calling on Xi Jinping to retire at the Twentieth Party Congress. It read in part:

From the Eighteenth Party Congress [in November 2012, the former Party General Secretary] Hu Jintao magnanimously ceded all of his positions and handed control over the party-state-army to you holus-bolus. At the time you were moved enough by Mr Hu’s gesture to praise him for his ‘outstanding political virtue’. Well, why can’t you demonstrate a similar political probity this time around?

The whole world has got wind of just what kind of smelly farts had been building up in that paunch of yours the moment you pushed through the revision of the Chinese Constitution [in early 2017, allowing for a state leader to serve more than two consecutive terms in office]. It is an unspoken rule within the Party’s Politburo that leaders should retire before they reach their sixty-eighth year, not to mention the end of their term in power. Since you criticise others for not following guidelines set down by the Party, why don’t you take a good look at yourself? By promoting a cult of personality you are in flagrant breach of the Party Constitution.

You have been quick to criticise people for forming factions and cliques but you have made a practice of appointing your own favourites; you have surrounded yourself with your own gang; and, you have been more than willing to reward shameless sycophants with positions of power. Take a good look at your ‘Zhejiang Army’, your Fujian Faction and your Shaanxi Clique, not to mention the old buddies and classmates who’ve enjoyed favour during your tenure. How many members of this mob of toadies really have the ability to serve the nation meaningfully or really have sufficient talent to be appointed to lofty office?

The ancient classic I Ching says:

‘Disaster attends upon those whose personal virtue does not match their office. If their ambition exceeds their intelligence, if their abilities are meagre and their responsibilities weighty, no good can possibly come of it.’

The ancient philosophers could see far into the future and these lines from I Ching suit you to a T.

— from China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season (Part III)

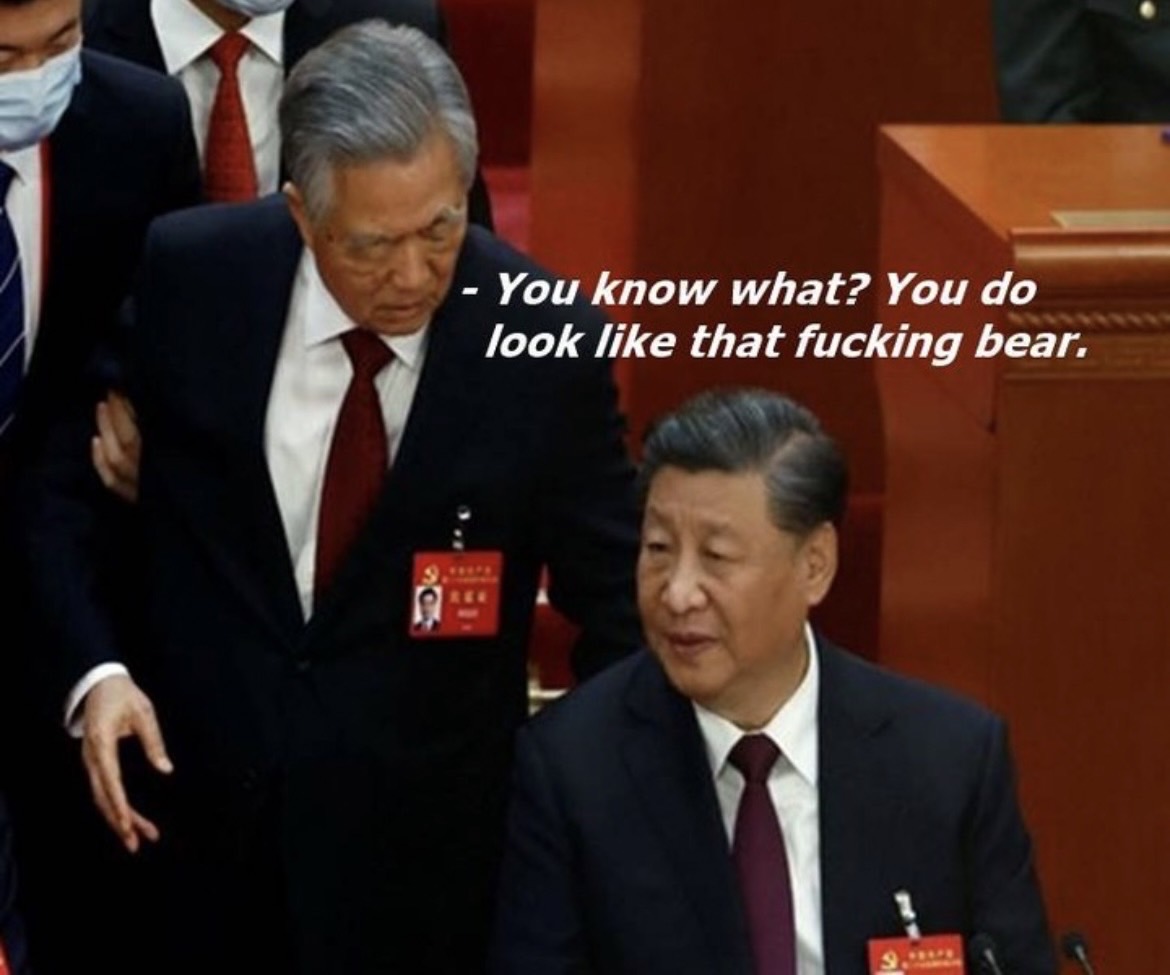

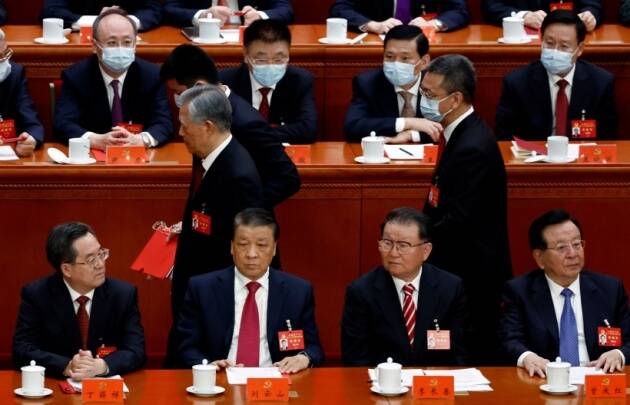

There were media reports that, on 16 October 2022, the first day of the Twentieth Congress of China’s Communist Party, Hu Jintao had failed to applaud Xi Jinping’s two-hour long report to the convocation as custom would usually demand. There was immediate speculation as to whether this was a gesture of disapproval, a sign of disrespect or merely a reflection of Hu’s waning health.

On 22 October, the final day of the congress, further conjecture regarding the relationship between the former and regnant Party General Secretaries was sparked by the fact that Hu Jintao was escorted out of the meeting. Was it ill health? Or, as many guessed, Hu Jintao was urged/ hijacked after attempting to raise a voice of protest. One popular story postulated that Hu had not been informed in advance that none of the leading comrades formerly associated with him as part of the so-called ‘China Youth League faction’ would be elected to the new leading presidium of the Party’s Central Committee. Another popular account holds that Hu was ‘triggered’ by the unexpected absence of the name of his son, Hu Haifeng, on the list of new Central Committee members.

It is presumed that Hu only became aware of this when he caught sight of the name lists for the new Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee. Before he could make a peep, Hu was bundled out of the Great Hall of the People.

Hu Jintao, former president of the People’s Republic of China, Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Liberation Army and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party was effectively ‘de-platformed’ in front of delegates to the Twentieth National Party Congress and representatives of the international media, who caught the whole exposure on camera.

***

A video recording of the ‘Will He Stay or Will He Go’ Incident at the closing session of the Twentieth National Congress of China’s Communist Party, Great Hall of the People, Beijing, 22 October 2022

And:

- Agnes Chang, Vivian Wang, Isabelle Qian and Ang Li, What Happened to Hu Jintao?The former Chinese leader was abruptly escorted out of a highly choreographed meeting of the Communist Party elite. Here’s what the videos show., New York Times, 27 October 2022

***

Here we offer some observations on this dramatic incident by Wu Guoguang 吳國光, a Senior Research Scholar at the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions. Wu is also a Senior Fellow on Chinese Politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis and the author of China’s Party Congress: Power, Legitimacy, and Institutional Manipulation (Cambridge University Press, 2015). On 23 October 2022, the day after the Twentieth Party Congress concluded, Wu discussed Hu Jintao’s exit with Li Yuan 袁莉, a noted journalist, author of the New New World column for The New York Times and the creator of ‘Who Gets It’ 不明白播客, a Chinese-language podcast.

We are grateful to Li Yuan for permission to translate and publish material from her conversation with Wu Guoguang (吳國光, 20大結局與中國未來走向, Episode Twenty-two in the ‘20th Party Congress Special’ of ‘Who Gets It’, 23 October 2022).

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

23 October 2022

***

From Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season: Part I; Part II; and, Part III, China Heritage, 6, 14 & 16 October 2022

- ‘The Unseating Incident’ — a letter to Xi Jinping, my fellow Tsinghua alumnus, about our elder, Hu Jintao, China Heritage, 26 October 2022

Related Material:

- A former Chinese leader was ushered out, leaving many questions., The New York Times, 23 October 2022

- Predecessor’s Sudden Ejection Highlights Xi’s Power, Asia Sentinel, 23 October 2022

- 二十大換了人間,習近平執行團隊天下驚色;政治局怎麼少了一個人?操控意外,差額差了差?,華爾街論壇二十大特別節目, 2022年10月23日

- 中國研究院(王軍濤,鄧聿文,馮勝平,何頻), 習近平怎麼做到獨攬大權?政治局委員與常委:執行團隊;胡錦濤退場,李克強裸退,胡春華失局:團派團滅;李強的國務院之變;軍委班子的作戰傾向, 明鏡電視, 2022年10月23日

- Evan Osnos, Xi Jinping’s Historic Bid at the Communist Party Congress, The New Yorker, 23 October 2022

- 吳國光, 習近平一人獨大 但新派系隱現,自由要州電台,2022年10月24日

- Who’s on First? — China’s Successive Failures, China Heritage, 20 November 2017

- China’s Highly Consequential Political Silly Season: Part I; Part II; and, Part III in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

- Li Yuan 袁莉, ‘20th Party Congress Special’ in ‘Who Gets It’ 不明白播客 —— 20大特輯, a Chinese-language podcast with links to transcripts of the conversations. See: Episode 16, Xu Chenggang on hopes for China’s economy; Episode 17, Jin Dongyan on Zero-Covid; Episode 18, Victor Shih on Party power struggles; Episode 19, Jiang Xue and Zhang Jieping on the media; and, Episode 20, Wu Guoguang on resistance in a totalitarian age

***

China’s Political Puppet Theatre

Wu Guoguang

Politics is often compared to a drama; this book will examine a theater in which dramas of political power are performed for the purpose of fabricating, ritualizing, and displaying the legitimacy of undemocratic leaderships. The chapters that follow provide an institutional analysis of how this theater stages, operates, and crystalizes the drama while, simultaneously and even more significantly, various behind-the-scenes manipulations drive, craft, and define the performance in every aspect, including, to continue the use of theatrical metaphor, personas, plots, tones, gestures, and even audiences. Together these create a hypocrisy called legitimacy, in which political power is readily accepted by all who are involved and, to a lesser degree, by those who are engaged to watch. This is the story of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party; an investigation of its politics and institutions shall be the focus of this book.

… [T]he fascinating secret of the Party Congress lies in its strange combination of political hollowness and institutional holiness; it is such institutional duality, incongruity, and self-contradiction that all rest at the center of both the empirical and the theoretical inquiries of this monograph. It shall highlight the institutional inconsistency of politics between norms and games, between principles and practices, and between constitutional stipulations and power operations. By investigating the institutional details within the running of the Party Congress, the book argues that institutional manipulations are manifested in a variety of ways, specifically by arising within this institutional inconsistency; by harnessing and maneuvering various norms, rules, and procedures; by actualizing power dominance of “puppet” participations; and by demanding the pompous display of so-called “confirmative legitimacy” in which elite consensus and the political loyalty of those who are involved overwhelm the participants’ autonomous articulation of various interests and substantial representation of constituencies. Conceptually, it suggests a theory of authoritarian legitimization that focuses on power domination, institutional manipulation, and symbolic performance in a political and institutional context that differs greatly from a democratic one but “steals the beauty,” so to speak, from democracy in order to legitimize contemporary authoritarianism. The book, therefore, shall decode and explain the myth of China’s Party Congress by revealing its institutional hypocrisy in the form of its blending of political rehearsals and public display together for the purpose of legitimizing the leaders who have already come to power as well as those who are designated to come into power to the degree that their well-tailored political platforms and personnel plans are well accepted, adopted, and applauded.

— from Wu Guoguang, Introduction: China’s Party Congress as the theater of power in China’s Party Congress: Power, Legitimacy, and Institutional Manipulation, Cambridge University Press, 2015

***

***

The Theatrical Denouement of a One-man Show

an excerpt from Wu Guoguang 吳國光 and Li Yuan 袁莉

‘The Upshot of the Twentieth Party Congress and China’s Future’

20大結局與中國未來走向

23 October 2022

Yuan Li: Can we talk about Hu Jintao leaving the stage? It was undoubtedly the most dramatic episode of the Twentieth Party Congress. You remarked in a tweet that the drama as well as the political significance of this moment might possibly be even greater than Mao Zedong’s performance at the Ninth Party Congress [in April 1969]. Hu’s departure became a focal point of the whole congress. What the heck do you think was really going on?

Wu Guoguang: In the process of writing China’s Party Congress: Power, Legitimacy, and Institutional Manipulation I looked at a lot of historical material, including some old videos. In particular, I took note of two episodes at the time that Mao Zedong convened the presidium during the Party’s Ninth Congress.

The first was when delegates voted in the members of the new presidium. Mao called for a show of hands by those who supported the candidates whose names had just been read out. He then said: ‘The successful candidates should now take their seats on the stage [in the ranked seats behind Mao and the other members of the Politburo].’ The thing was, however, that they were sitting up there from even before the vote was taken. That was because they all knew that the formal process of electing them was merely for show. Turning around Mao saw them all sitting there behind him. Compared to Xi Jinping at least Mao had a rather sardonic sense of humour — though, in the scheme of things it was only a minor virtue. Anyway, after a moment’s awkwardness he jokingly remarked: ‘It would appear that my comrades are all one step ahead of me!’ And that was the end of that.

But that was followed by a second, even more revealing, act: the gathering then had to elect a chair of the presidium. As Mao was presiding over the meeting he spoke up: ‘I think Comrade Lin Biao should be the chair, don’t you all agree?’. Everyone was stunned and Lin Biao was nonplussed. He immediately jumped up and declared: ‘That won’t do at all: our Great Leader Chairman Mao will, of course, be the chairman of the presidium.’ Lin then bellowed at everyone in the hall: ‘Don’t you all agree, comrades?’ Naturally, this was followed by universal acclamation and applause.

What so enthralled me about this particular scene — after all, everyone said that all those Party officials simply did what Chairman Mao told them to do — was why didn’t they simply snap to and do what he suggested? Chairman Mao moved that Comrade Lin Biao should be the chair, so why didn’t they all chorus ‘Yes!’? In fact, each and everyone of them were more than capable of making a judgment call; they instinctively knew the right thing to do on each and every occasion. So, at this juncture, they knew that although Chairman Mao said Lin Biao should be the chair of the congress, he was quite possibly having a poke at Lin, or making fools of all of them. Either way, Mao was known to be quite a trickster so, when he made that suggestion, everyone present knew that if they hesitated they would not be judged as being disloyal to the Chairman. After all, they knew full well that Mao wanted the position of chair for himself and the power that came with it. From the video recording of the scene you can see just how flustered Lin Biao was. He knew full well that Mao was tormenting him and that he was enjoying playing him for a fool.

[Note: For more on the Ninth Party Congress, see The Ayes Have It, China Heritage, 18 October 2017.]

In fact, theatrical scenes like this have happened at just about every congress of the Communist Party, although back then they were much better at keeping things under wraps. That added to the fact that there wasn’t the kind of media access you have today, not to mention all these recording devices. Take a meeting the Party held in the Yan’an era [in the early 1940s], for example. Representatives at that Party gathering complained that although they were constantly told that they had to denounce Wang Ming [a former Party leader purged by Mao who was being denounced for his dogmatism] they had never laid eyes on him. Since Wang was incapacitated by illness, Mao had him brought up on the presidium on a stretcher so all the representatives could take a gander at him for a few minutes. Some even remarked that Wang was a strikingly handsome fellow. Of course, it was all pure theatre, but back then there were no video cameras.

袁莉:… 我們談談一下20大最戲劇性的一刻,胡錦濤離場。您在推特上寫道,其戲劇性與政治含義可能超越了九大上毛澤東表演的那一幕。他們究竟在搞些什麼?這成了中共20大的最大熱點。您能解釋一下嗎?

吳國光:我在寫黨代會這本書的時候,看到一些資料,包括一段錄像。毛澤東在九大主席團開會的時候,有兩個場景讓我覺得很有意思。第一個,毛澤東組織會議,讓大家選舉主席團委員,念完名單,毛澤東就說,同意的舉手,大家舉手了,主席團委員就選出來了,毛澤東就說,「現在請主席團委員上主席台就座」,但實際這些主席團委員已經在主席台坐好了,還沒選,他們都坐好了,因為他們都知道這個選舉本來就是瞎胡鬧的,本來就是走個過場。所以毛澤東轉臉一看,主席台坐得滿滿的,毛澤東覺得有點尷尬,但是毛澤東和習近平相比,有一個小小的優點,他有點玩世不恭、有點幽默感,他就說,「哎呀,看來同志們都是趕早不趕晚啊!」這個事情就過去了。接下來這一幕,更有意思。接下來要選主席團主席,毛澤東組織會議,他說,「我提議林彪同志當主席好不好?」這下全場都傻了。這時候最緊張的就是林彪,林彪一下子站起來說,「不好不好,偉大領袖毛主席,當(主席團)主席!」然後對著底下喊,「同志們說好不好啊?」大家都說好,嘩啦啦鼓掌。

我為什麼對這個場景特別有興趣,大家都說,這些黨的官員什麼時候都聽毛主席的話,但為什麼這時候怎麼不聽毛主席話呢?毛主席說選林彪同志當主席,他們怎麼不說好?實際上,這些人是有自己判斷力的,他們知道在什麼場合做什麼事情是正確的,所以這時候即使毛澤東說讓林彪當主席,他們也知道毛澤東可能在調戲林彪,可能在戲弄代表,總而言之,毛澤東玩世不恭給你來這麼一下子,不是代表的政治不忠誠,不同意毛澤東讓林彪當主席,他們都知道毛澤東想要當主席、要有權力。從來錄像上看,林彪是最慌張的,他知道毛澤東把他架在火上烤,毛澤東要調戲他、戲弄他。

其實幾乎每一次黨代會上都有一些戲劇性場面,但是過去保密保得更好,沒有那麼多信息傳輸渠道,也沒有那麼多的錄像。比如在延安那個開會,把王明用擔架抬到主席台上,因為代表們說,老讓我們批王明,王明長什麼樣我們都不知道,能不能讓我們看一眼?那時候王明已經病了,不能走了,就用擔架把王明抬到主席台,放了幾分鐘,每個代表看一眼王明長什麼樣,有人還說王明長得真清秀。這個很有戲劇性,但是當時沒有錄像。

***

***

The thing about Hu Jintao’s ‘de-platforming’ is that, regardless of the video evidence of the incident there is no way of knowing what really happened. Needless to say, social media platforms have been abuzz with speculation. Although I don’t want to be overly critical of anyone who wants to offer an explanation, I must admit that despite everything I’ve seen, I remain unconvinced. I really don’t like all of these instant attempts to offer a definitive judgement of an event on the basis of the most scanty evidence. For my part I prefer not to indulge in that kind of speculation. What I did see was that two people approached Hu Jintao to escort him out and that Hu obviously did not want to leave, or rather Hu’s repeated attempts to stay seated. That’s what the video shows, though when I say that Hu Jintao ‘did not want to leave’, I’m speculating about his real intentions and I may well be overstating things. What we do see in the video, however, is that Li Zhanshu [Politburo member and head of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress] tried to stand up, maybe to offer a hand to Hu Jintao, or a word of advice or caution, though we can’t be sure. What we do know is that Wang Huning [a Politburo member and Xi’s ideological guide] pulled Li Zhanshu back down so that he remained seated.

Furthermore, as Hu Jintao was leaving we could see that he said something to Xi Jinping after which he patted [Premier] Li Keqiang on the shoulder. On Twitter people have been asking if anyone can lip read. My response was to say that the bar for studying Chinese politics really is being raised pretty high: up until now people were supposed to be expert in facial micro expressions, now that was no longer enough — you need to be able to lip read, too. If this trend continues I’ll soon be out of a job.

Regardless of the fact that there’s no way we can know what actually took place, there is no doubt that for such a vignette to unfold during the closing ceremony of the Communist Party’s Twentieth Congress was quite out of the ordinary. For a former Party leader to leave the congress in such a manner — regardless of whether it was for a legitimate health reason or due to some political disagreement — what was truly extraordinary was the fact that neither Xi Jinping nor Li Keqiang made any effort to extend even the most rudimentary courtesy to their former superior. Neither said anything to Hu Jintao, nor for that matter did they make any attempt to explain to congress representatives what was happening. Nothing like: ‘Comrade Hu Jintao is taking a leave of absence due to ill health and we should all express our best wishes’, or the like. Even if they were unwilling to offer a few kind words, at least they could have come up with some explanation. To do so is nothing more than a matter of basic decency.

Instead, what we saw was all those men who had been elevated to power by Hu Jintao like Li Keqiang, Wang Yang and Hu Chunhua, as well as many others, sitting there nervously — no expressions on their faces, no sign of understanding for Hu or sympathy. It was just this clutch of wooden men, frozen and dumbfounded, witnessing it all in stony silence.

[Note: See Ye Kuangzheng, Hollow Men, Wooden People, China Heritage, 24 December, 2017]

Li Zhanshu was the only one who was mentioned in a favourable light on Chinese social media. Of course, we have no ideas as to what his motives were, but at least he responded to the situation like a normal human being. Maybe he was trying to give Hu Jintao a hand?

Yuan Li: And he wiped his own brow…

我看到胡錦濤的錄像,要害是,我們不瞭解到底發生了什麼。當然社交媒體上有各種各樣推測。我對做推測的人沒有任何批評,我也不偏向於任何一種推測。但我對這種看到一分東西,馬上得出100分結論的斷言,我是很不喜歡這麼做,我個人是絕對不會這麼去做任何推測。我只是看到了,那兩個人要架胡錦濤走,胡錦濤在那裡不想走,至少胡錦濤一而再再而三要坐下,這是我們看到的。我說「胡錦濤不想走」,這是我推測他內心,那這可能是有點過分了。但我們也看到了,栗戰書試圖站起來,好像要扶一下胡錦濤,也可能是勸說,都不知道,但是我們看到了王滬寧在後邊拉了栗戰書一把,讓他坐下;我們也看到了胡錦濤離開的時候,給習近平講了一句話,然後拍了一下李克強的肩膀。推特上有人留言說,有人會讀唇語嗎?我還回了一句,研究中國政治的門檻越來越高了,前一段時間是相面,現在要讀唇語,再這樣搞下去我肯定沒飯吃了。這個事情到底是在做什麼,我們不知道,但不管怎麼樣,在中共黨代會全體大會閉幕這一天發生這一幕,無論如何,所有人都感覺,這是不尋常的。前任黨魁被這樣離場,無論是善意還是惡意、無論是政治原因還是健康原因,這樣離開會場,習近平也好、李克強也好,最低限度可以說兩句客氣話,或者向會場的代表解釋一下,「胡錦濤同志現在由於健康原因不得不離開會場,我們大家對他表示歡送」。或者你不歡送,解釋這麼一句,「很遺憾胡錦濤同志不能如何如何」,這是人之常情吧。但是,我們看到這一幕,那些胡錦濤過去重用的人,李克強也好、汪洋也好、胡春華也好,還有很多人都高度緊張地坐在那裡,沒有任何表示同情,沒有任何表示安慰,都像木頭人石頭人一樣,呆若木雞地看著那一幕。栗戰書這次倒是在社交媒體上看到很多好評,不管他什麼用意,他至少表現出了一個人本能的反應,動了一下,想去(扶一下胡錦濤)。

袁莉:他還擦了把汗。

Wu Guoguang: What was glaringly obvious was the fact that the elite of the Communist Party was gathered in one place and we could see just what kind of people they really are. They lack basic humanity, the most rudimentary kind of empathy. Here was Hu Jintao, the former highest leader of your Party and a man who had given so many of you political opportunities. And how do you treat him now? You can go on and on about how you think about and work for the Chinese masses as much as you like. You can regurgitate all that prattle about The People, but [having witnessed this scene] who’ll believe anything you say? Don’t any of you have even a skerrick of humanity left in you?

This incident demonstrated the tragic reality of Chinese politics and the fundamental lack of human decency in the Communist Party.

Yuan Li: It really was a chilling display. Regardless of what you think of Hu Jintao he is nonetheless a fellow human being, someone who should be treated with basic civility. There was no sign of that.

[Note: Our sympathy for Hu Jintao is limited to this distasteful episode. Hu is remembered for the brutal suppression of dissenters during his dark reign in Tibet (1988-1990) and, among many other things, the attack on Charter 08 and the murderous incarceration of Liu Xiaobo. See You Should Look Back, 1 February 2022.]

Wu Guoguang: In the case of an elderly person, or someone who is old and frail (maybe Hu really wasn’t ill [as the official Xinhua News Agency would have it], although everyone knows that he is quite sickly), let’s set aside the fact that he is a former Party leader and all considerations of personal advantage — if any of us were to come across an elderly person who was obviously ailing, wouldn’t we evince sympathy or compassion? If that person was incapacitated or was having difficulty moving around, wouldn’t we all volunteer to give them a hand?

To anyone who has any illusions about the leadership of the Chinese Communists — people who still think that they really want to pursue meaningful reform, or even democratic change — let me say this: you are as lacking in basic humanity as they are. I say that because you are placing your hope for meaningful human outcomes in China on a group of people who fundamentally lack humanity. Think about how illogical your approach is. I’m sure I’ll get attacked online for saying that; in fact, you might want to delete this remark. Anyway, I’ll take whatever criticism anyone wants to make of me.

Yuan Li: I really appreciate the fact that [in your book] you describe party congresses as ‘the theatre of power’. Every aspect of these meetings, right down to the pouring of tea for delegates, is carefully scripted and painstakingly rehearsed. Then, suddenly, something like the Hu Jintao incident occurs and from the way that they all respond you get a fleeting glimpse of what is really going on deep down inside them all.

Wu Guoguang: We usually expect to be enthralled and entertained by a theatrical production, but in the case of the Communists the performances are wooden. I should have called my book ‘The Puppet Theater of Power’.

吳國光:可以看得出來,會場里,這些中共最精英的人,都是些什麼人啊?還有人性嗎?還有基本的人情嗎?這是你們自己的前最高黨魁,很多人,你們的政治生涯是在他手裡得到很大好處的。現在,你還說對老百姓如何如何,對人民怎麼怎麼樣,還有人信嗎?你們這些人還有一點點人味兒嗎?這暴露了中國政治最大的一點,從基本人性來看,多麼的可悲。

袁莉:冷酷到了極點。不管胡錦濤是一個什麼樣的人,但作為基本的人,應該表現出來的一點點起碼的關懷都沒有。

吳國光:作為一個老人,作為一個病人,(也許這次不是因為病而離場,但是他身體不好大家都知道),我們不講他是前黨魁,不講各種各樣的利益考慮,我們所有人見到一個陌生的老人,一個病人,我們都會對他表示同情的啊?他如果有動作不方便的話,我們都可能上去扶他一把。

如果還有人對這個黨的領導層報有各種各樣的自以為是的要求改革、要求民主的幻想,我只能講,你也和他們一樣沒有多少人性,因為你把這些有人性的東西寄託在這些沒有人性的人身上,你想想這是什麼邏輯?我講這話我就等挨罵,你可以把這句話剪出去,我等著挨罵。

袁莉:所以我覺得您那本書《權力的劇場,中共黨代會的制度運作》,我覺得「權力的劇場」取得特別好,它就是一個權力的劇場,political theater,每一步包括倒茶都是被高度訓練過排演過的,然後出了這麼一個事情,然後這些人表現出來的,其實是他們內心深處最真實的想法嗎?

吳國光:其實我應該用「權力的木偶劇」。我們一般講,劇場里表演很生動活潑很有吸引力的,但是我看他們是一場木偶劇。….

***

Source:

- 吳國光, 20大結局與中國未來走向, Episode Twenty-two in the ‘20th Party Congress Special’ of Li Yuan’s 袁莉 podcast series ‘Who Gets It’ 不明白播客 —— 20大特輯, 23 October 2022

Wrong Way, Turn Back

An excerpt from an interview with Joerg Wuttke in which the President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China sums up the 20th Party Congress and shares his views on the future economic and foreign policy under Xi Jinping.

Interviewer: Would you say that the growth model that has driven China over the last three to four decades is dead?

Jörg Wuttke: Yes. That was brought home to us symbolically with the forced departure of ex-president Hu Jintao.

Interviewer: How did you interpret this moment when Hu Jintao was led out of the Great Hall of the People on Saturday?

Jörg Wuttke: For me, it was the symbolic end of the old era. This also means that the old model, which was based on consensus between the different Party factions, is dead. Now the President has set his direction and he no longer tolerates dissent. The removal of Hu is symbolic of the fact that Xi has done away with the old politics and that de facto only he is in charge now. No senior Party official budged, no one supported Hu Jintao. Everyone sat there with a petrified expression. This was not a case of ill health on Hu’s part. I guess you have to get used to the fact that everything will become much more autocratic in China.

Sie würden also sagen, dass das Wachstumsmodell, das China in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrzehnten angetrieben hat, tot ist?

Ja, das wurde uns geradezu symbolisch mit dem forcierten Abgang von Ex-Präsident Hu Jintao vor Augen geführt.

Wie interpretieren Sie diesen Moment, als Hu am Samstag aus der Grossen Halle des Volkes geführt wurde?

Für mich war es das symbolische Ende der alten Ära. Dazu gehört auch, dass das alte, auf Konsens zwischen den verschiedenen Fraktionen innerhalb der Partei ausgelegte Modell tot ist. Jetzt hat der Präsident seine Richtung vorgegeben, und er duldet keine Widerworte mehr. Die Entfernung von Hu steht symbolisch dafür, dass Xi die alte Politik abgeschafft hat und dass nur noch er das Sagen hat. Kein hoher Parteifunktionär hat sich geregt, keiner hat Hu Jintao geholfen. Alle sassen mit versteinerter Miene da. Das war kein Krankheitsfall von Hu, er wollte wahrscheinlich Einspruch erheben und seine Politik und seine alten Weggefährten schützen. Man muss sich wohl damit anfreunden, dass in China alles sehr viel autokratischer wird.

— from ‘China Used to be a One-Way Street of Happiness and Rising Prosperity, But That’s Over Now’, The Market, 25 October 2022

***