Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix V

迥

The GOP in the United States of America and the CCP in the People’s Republic of China have long demonstrated eerily similar traits: an obsession with distorted historical narratives coupled to delusional nostalgia; the heroic defense of patriotic education; destructive sectarian political behaviour; intolerance of dissent and enmity towards civil society; a proclivity for rule by secretive cabals of power-brokers; a crippled vision of individual rights and collective responsibilities; a worldview based on what in recent years has become known as ‘fake news’; a fixation on conspiracy theories and systemic paranoia; the promotion of hate and resentment; self-affirmation provided by a claque of toadies, ambitious politicians and unprincipled media figures; an admiration for and the cultivation of oligarchs both at home and abroad; an obsession with race and ideological rectitude shored up by glib sophistry; the targeting of minorities for political advantage; the drumbeat of militarism; an apocalyptic view of the world; and, a penchant for rhetorical warfare, among many others. These characteristics shared by both political organisations are at their core informed by a fundamental disdain for democracy, the rule of law, equality, independent critical thought and free speech.

During the presidency of Richard Nixon, the GOP’s Southern Strategy and the Powell Memorandum, commissioned in 1971, contributed significantly to the long-term drift in American politics. As we commemorate Nixon’s China trip in February 1972, we also remember the more baneful aspects of his legacy.

In 2022, the three great powers — the former Soviet Union, the United States and China’s People’s Republic — that clashed during the Cold War decades coexist in an uneasy new configuration. The Soviet Union is now the Russian Federation ruled by the autocrat Vladimir Putin; China is dominated by a willful strong man of its own, Xi Jinping; and, for its part America struggles with the virulent legacy of Donald J. Trump, the GOP’s despotic dotard. The three hegemons — two of which hold the reins of power while the third plots a second coming — hold sway over their respective ‘empires of lies’ and immense destructive potential.

***

I am grateful to Orville Schell, Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society in New York, for his kind permission to reprint ‘Dissing Dissent’, an essay by his late wife Liu Baifang, in our series ‘1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China’.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

26 February 2022

***

1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium Appendix V 朝 — Nixon in China, consisting of nine sections: 撼 — A Week That Changed The World; 見 — A storied Handshake, an excised Interpreter & a muted Anthem; 蒞 — Nixon’s Press Corps; 迓 — ‘Welcome to China, Mr. President!’; 有目共睹 — 1978-1979, Year One of the Xi Jinping Crisis with the West; 迥 — Dissing Dissent; 鞭 — The President & The Chairman in Retrospect; and, 書 — A 2012 Letter to the Chinese Embassy

***

Further Reading:

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix I 捌 — A Beijing Winter after the Summer Olympics, 4 February 2022

- Spectres & Souls — Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021

- Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, New York: Random House, 2018

- On the Eve — Watching China Watching (XIII), China Heritage, 29 January 2018

***

Liu Baifang Worries About America

Orville Schell

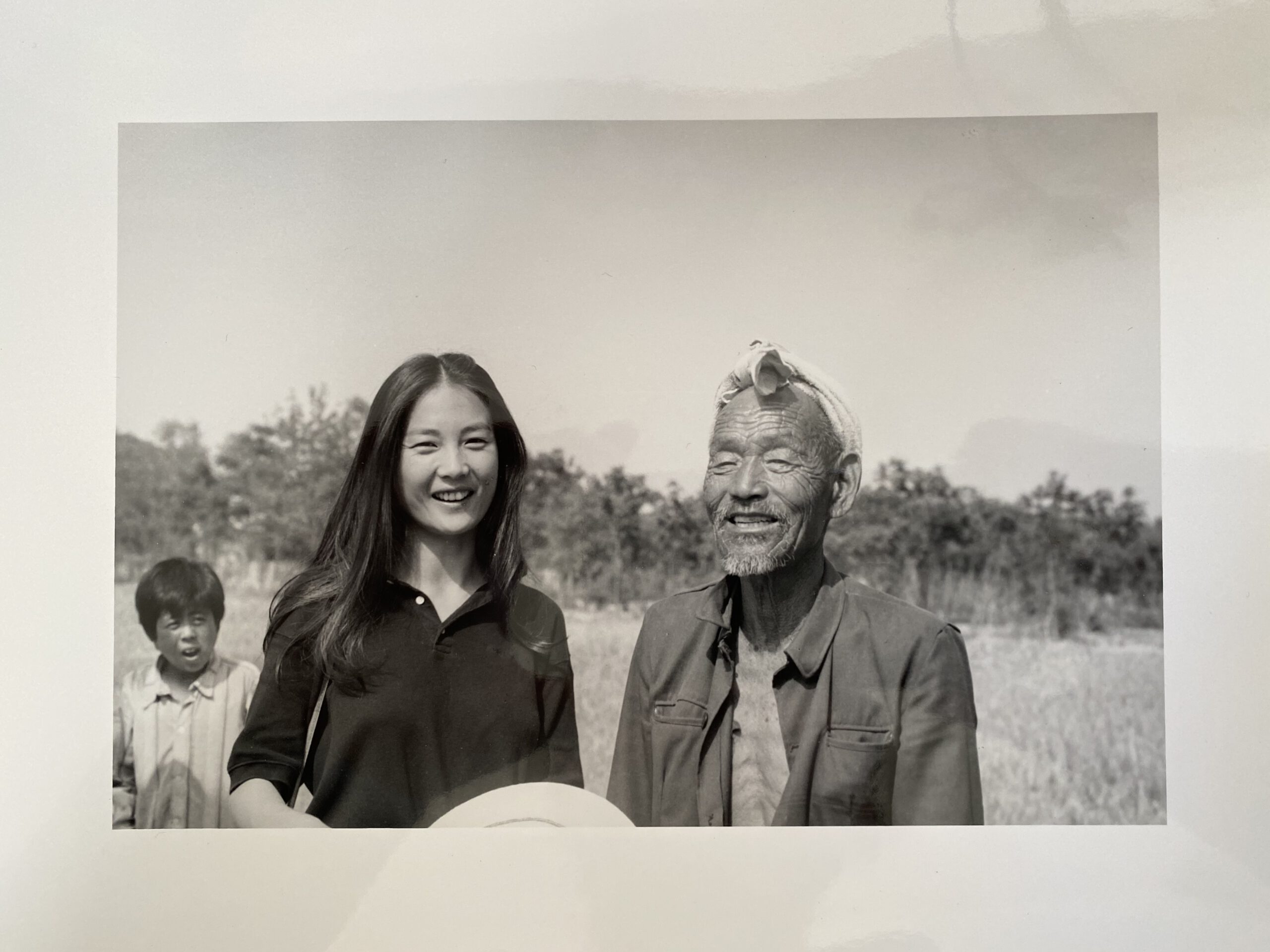

My now departed Beijing-born wife, Liu Baifang, grew up in Mao’s China as his most brutal political campaigns were sweeping the land during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. As a small child she almost died of starvation after Mao’s Great Leap Forward communized Chinese agriculture causing the deaths of some thirty to forty million people.

She arrived in the United States in the late 1970s just as “reform and opening” was being embraced by Deng Xiaoping and ultimately attended the University of California, Berkeley, where she felt only relief to at last be in a country where people were not imprisoned for speaking their minds.

However, in 2003 as she began observing the worrisome early signs of the Bush Administration’s attempts to suffocate political debate and create alternative realities when the real world collided with their own ideological positions, she began feeling a growing uneasiness. The thought that the very kind of political forces that she’d experienced in China during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, that she thought she’d vacated when she left China, were now proliferating in her new country left her uneasy. She often remarked on how dispiriting it was to observe the Republican Party evincing the same kinds of Leninist tendencies of group think, censorship of free speech, the manipulation of facts, and distortions of the historical record as she’d seen living under the Chinese Communist Party.

Despite her strong views, Baifang was one of the most un-self-promotional people I’ve known. She never sought the limelight, much less sought, or even accepted, invitations to publicize her own personal political views. Besides the article below that appeared in the Los Angeles Times in 2003, the only other time she ever expressed herself publicly was following the Beijing Massacre in 1989 when after returning home from Beijing, she consented to go on NBC’s Nightly News with Tom Brokaw to express her outrage over what had just happened in her natal city.

As numerous countries around the world are now once again moving toward authoritarianism, and as even the U.S. — especially under the administration of President Donald Trump – has shown that it, too, is no less vulnerable to autocratic tendencies than any other country, her editorial from almost two decades ago is perhaps worthy of reprise. For it reminds us that no nation – no matter how strong its democratic institutions – is exempt from the forces of nationalism, extremism, and even fascism; that there are always incipient forces in readiness just waiting to spring forth from the dark side of mankind’s experience to opportunistically take the political stage, just as we’ve recently seen these last few days in the Ukraine.

I thank Geremie Barmé for asking me to write these few introductory words in memory of my dear wife just a year to the day after her untimely death. I am proud to have her column reborn here in China Heritage.

Dissing Dissent

Liu Baifang

26 October 2003

Original editorial note: Liu Baifang, who emigrated from China in 1977, lives in Berkeley.

Lately, I find myself worrying about my adopted country, the United States. I’m alarmed that dissent is increasingly less tolerated, and that those in power seem unable to resist trying to intimidate those who speak their minds. I grew up in the People’s Republic of China, so I know how it is to live in a place where voicing opinions that differ from official orthodoxy can be dangerous, and I fear that model.

Like so many others, I arrived in the U.S. enormously relieved to have left my “socialist” homeland. During Mao Tse-tung’s “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” intellectuals were persecuted, physically intimidated, imprisoned and, all too frequently, killed. Educated people, known as “the stinking ninth category,” were terrified into political silence after witnessing the dire consequences of voicing any suggestion of dissenting views. My parents were engineers, educated people, and so my family was separated and then “sent down” to labor among peasants in the countryside. We were punished merely for being educated.

During this time, there was a dizzying succession of “correct political lines” and an endlessly changing kaleidoscope of labels used by the Communist Party and the state to isolate anyone who disagreed with official thinking. People who criticized the government were dubbed “counterrevolutionaries,” or “capitalist roaders” or “running dogs of American imperialism.” They were “bourgeois liberals” or “wholesale Westernizers.” People tarred with such labels lost friends, jobs and reputations — even spouses. Families were destroyed. When it came to politics, no room was left for ambiguity, doubt or disagreement. We had to pretend to believe that our leaders always knew best, and to toe the political line. With all criticism stifled, China lost the ability to examine and correct even its most abjectly self-defeating policies.

As students, we had to endlessly study the works of Marx, Lenin, Engels, Stalin and Mao. One of the main tenets of this totalitarian system was what Lenin called “democratic centralism,” which prescribed “full freedom in discussion, complete unity in action.” The Party hierarchy embraced the “unity in action” portion of the message, but true free discussion was out of the question. As Mao said: “The minority is subordinate to the majority, the lower level to the higher level, the part to the whole, and the entire membership to the Central Committee … . We must combat individualism and sectarianism so as to enable our whole party to march in step and fight for one common goal.”

Those courageous or foolish enough to dissent were marked and then ruthlessly hounded into submission. The suffocation of discussion and debate — never mind the suicides and killings — crippled every realm of life, from science and literature to politics, economics and even the most basic human interactions. Noted astrophysicist Fang Lizhi told me that he had been unable to teach the big-bang theory of cosmology during the Cultural Revolution because the notion of an expanding universe was a manifestation of “bourgeois idealism” that did not fit with Engels’ idea that the universe must be infinite in space and time. There were myriad other examples everywhere around us of the ways in which the nation’s ability to find the truth were affected by this savage intolerance.

So why are these 40-year-old stories of political rigidity in a faraway land relevant in America today? I’m certainly not suggesting an equivalence between the political climate in America now and China then. But I am getting a whiff of the Leninism with which I grew up in the air of today’s America, and it makes me feel increasingly uneasy.

I could not help but think about China recently during the flap over former State Department envoy Joseph C. Wilson IV, who angered the White House with his finding that documents suggesting Iraq had tried to acquire nuclear material from Niger were in all likelihood forged. The administration went ahead anyway in citing the documents as part of its justification for invading Iraq. After Wilson wrote an article for the New York Times calling attention to the deception, someone in the administration allegedly leaked information to the press that Wilson’s wife was an undercover CIA agent. In China, it was not just one official like Wilson who was targeted for retribution but countless individuals, many of whom spoke unwelcome truths about their country, only to be rewarded with public shaming or prison sentences.

When I hear our president, in this time of soaring deficits, continue to insist that tax cuts are the key to national prosperity, even though countless economists have warned against them, I cannot help but remember how Mao used to say that China didn’t really need “experts,” only people who were Red. Mao’s inner circle attacked anyone who questioned whether “class struggle” would ultimately solve all China’s problems.

I also worry about what I see happening to our media and freedom of the press. The Bush administration has repeatedly made clear that it does not welcome skeptical, penetrating questions. White House spokesmen have made it clear that they view the Washington press corps as a corrupting “filter” on the news. Reporters and publications seen as unsympathetic to the administration’s goals find it harder to get access to officials. Recently, Bush made an end run around the entire White House press corps by going directly to regional television outlets in the hopes of being better able to spin the news at the local level.

Indeed, Bush press conferences, which I enjoy watching, seem to me to have become more and more like those held by the Chinese Communist Party: Nothing but the official line is given, and probing questions from reporters, which are crucial to advancing the public’s understanding of the government’s actions, are often evaded or ignored. Moreover, as Hearst Newspapers columnist Helen Thomas, dean of the White House correspondents, recently learned, too-persistent questioning on sensitive issues means that the next time you are ignored, even relegated to the back row of the briefing.

Open inquiry, freedom of expression and debate are essential parts of a well-functioning democracy. When leaders disdain debate, ignore expert advice, deride the news media as unpatriotic and try to suppress opposing opinions, they are likely to lead their country into dangerous waters. Even China now seems to have learned how dangerous it is to completely control the press — witness the attempted cover-up of the SARS epidemic — and to be loosening up a bit.

Thus, it makes me all the more discouraged to find the U.S. moving backward. When honest government officials and outspoken citizens are ignored or, worse, marked for intimidation, it begins to seem that the Bush administration is acting more in keeping with Lenin’s notion of democratic centralism than with the founding fathers’ notion of the necessity for a sometimes inquisitive citizenry and a free press.

I am grateful to have become an American and to now belong to a country that has had an inspiring and enduring and true commitment to letting “a hundred flowers bloom,” as Mao, hypocritically, once said. What has made the U.S. such a beacon to people like me is that it has always been principled, confident and strong enough to let its people debate and criticize government policies without suggesting that the critics are somehow less than patriotic.

When our government loses its tolerance for a full range of views on national and world affairs, it is veering toward the authoritarian world that speaks in one voice, the very political model it has so often stood against — even fought against. I hope I will never again have to live in such a world.

***

Source:

- Liu Baifang, ‘Dissing Dissent’, Los Angeles Times, 26 October 2003

***