The Best China

Pierre Ryckmans, better known to readers under the pen name of Simon Leys, valued Jacques Pimpaneau as ‘a colourful character, original, a non-conformity, an oddball, cultivated, generous.’ (As quoted in Philippe Paquet, Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds, p.230.)

Shortly after the young scholars first met in Hong Kong in 1969, Pimpeaneau introduced Ryckmans to René Viénet, a former student of his at the Institut national des langues et civilisation orientales in Paris. When recalling his friendship with the two men years later, Ryckmans observed that,

‘In their generosity, in their originality, their wit, their courage and their intelligence, they stood out sharply from the sad, drab nest of vipers of French sinology.’

On one occasion, Pimpaneau invited Ryckmans and Viénet to dinner at his home at which Pierre, who had been collecting a mass of material on the Cultural Revolution, showed them ‘bundles of carbon copies and manuscripts of notes from out of a vegetable crate’. Viénet immediately suggested that it could form the basis of a book that would debunk the romantic ideas about Maoism fashionable within the leftist cenacles of the French capital. The resulting work, The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution, appeared in 1971, as much to the consternation of Maoist zealots then as it would be edifying for wannabe academic Maoists today — a ‘sad, drab nest of vipers’ if there ever was one — if they took the trouble to read it.

Both Jacques Pimpaneau and Simon Leys contributed to Peking Duck Soup, a 1977 documentary film directed by René Viénet, also known under the title Chinois, encore un effort pour être révolutionnaires (Once again, people of China, if you really want to be revolutionaries!).

***

Below, John Minford remembers Jacques Pimpaneau, who passed away in Paris on 3 November 2021.

— The Editor

6 November 2021

***

- Pierre-Antoine Donnet, ‘Hommage à Jacques Pimpaneau, éminent sinologue, mort à 87 ans’, Asialyst

***

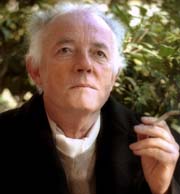

Jacques Pimpaneau (1934-2021)

John Minford

I learned today with great sadness that the wonderfully irreverent French ‘sinologue’ Jacques Pimpaneau died three days ago in Paris, after a long illness. I first knew Jacques in Oxford in 1970, when he was studying there with David Hawkes. Our children were the same age, and used to play together in the garden of his first wife Angharad’s family house on the Iffley Road. Over the intervening 50 years he has always been an inspiring example of how the study of China and the teaching of Chinese language, literature and culture can be a creative and exciting enterprise, despite the unrelentingly dreary and deadly efforts of university establishments and propaganda organisations across the world to imprint on that enterprise the kiss of academic death.

He himself saw among his predecessors in this lively, creative tradition the cultivated Swiss sinologue Paul Demiéville, and above all his own teacher at Oxford, the British scholar and translator David Hawkes. Among the students on whom he himself has had a profound influence must be ranked the prominent Swiss sinologue and art-critic Jean-François Billeter.

I last saw Jacques in April 2019 when I spent several hours chatting with him in a Montparnasse café, his wit and cultivation completely undiminished. I vividly remember wandering a few years earlier with him down the streets behind the church of St Germain des Prés, as he held forth with infectious enthusiasm, not about anything to do with China, but about Balzac and the house we were just passing where he had lived when writing La Comédie Humaine. Jacques was a most fascinating raconteur, his repertoire ranging from tales of the raffish French literary and artistic demi-monde of which he had often been a part during his life, to some of the more obscure byways of classical Chinese erotic fiction. (He co-translated the classic erotic novel The Carnal Prayer Mat 肉蒲團, using a pseudonym.) His skill as a teacher, and his ability to entertain and at the same instruct his students, were legendary in Paris. His sense of mischief can be seen in the delight he often had in telling his friends that his French surname derived from one of his shadier ancestors, who had been ‘a pimp’. He was unimpressed by the much-publicised attempts made by some of his more pretentious contemporaries to find in Chinese ‘philosophy’ a panacea for Western Aristotelian discourse. Of François Jullien he once remarked to me that his books might perhaps be of interest ‘if they were translated into French’…

In the summer of 2007 I visited him and his second wife Sylvie in their new home in Saint Rémy de Provence, and there I recorded a relaxed 40-minute interview with him in which he spoke (chain smoking as always) of his life as teacher and translator and in particular of his creation in Paris of the Kwok On Museum of Asian Puppetry and its later move to Lisbon. He not only collected and curated objects and costumes connected with all sorts of Asian puppet theatre, he loved to perform the plays himself, to keep them (and the culture they came from) alive. He was above all an artist.

During his lifetime, Jacques published countless works on Chinese literature and culture, mostly with the pioneering Arles publishing house of his friend Philippe Picquier, in which he passed on his wide reading and indefatigable scholarship with such joy and such a deceptively light touch. One of my personal favourites is the beautifully illustrated little book entitled Dans un Jardin de Chine (hardback edition, Picquier 2000), in which translated extracts from Chinese fiction, belles lettres and poetry, are woven together like a leisurely ramble round a Chinese garden.

Always at heart a true anarchist, Jacques sought above all to liberate himself from the constraints of the academic world, and to communicate in his own way to a younger readership his passion for all the good things Chinese, their literature, their theatre, art, joie de vivre, with never a nod to what might be considered politically or institutionally acceptable, either in Peking or in Paris. His unique voice and insight will be sorely missed, but an echo of his spirit will stay alive in his many wonderful books.