Spectres & Souls

The annual Double Tenth Day 雙十節 on 10 October commemorates the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, which led to the abdication of the ruling house of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China. Since 1912, it has been the national day of the Chinese republic.

In 2021, China Heritage marks the Double Tenth by publishing a translation of ‘As if to Break Free of the Autocratic Gloom’ 走出專制統治黑暗, a speech delivered by Dai Qing 戴晴 in March 2011. In her remarks, Dai commemorated the centennial of a revolution that promised an end to China’s millennia-old autocracy. As things turned out, however, for most of the twentieth century new forms of despotism dominated China’s political landscape, both on the Mainland and on Taiwan. From the late 1980s, the clash between two ideologically disparate forms of Chinese authoritarianism transmogrified into a contest between the one-party Communist state of the People’s Republic and the market-oriented constitutional democracy of the Republic of China.

The civil war that broke out in 1927 following a short period of Nationalist-Communist collaboration continues to this day. On Taiwan, although the promise of the Xinhai Revolution was only realised some eighty years after 1911, it is now under constant external threat. On the Mainland, a reinvigorated monocracy that is heir to a dark past holds sway. The People’s Republic claims that it is the legitimate successor regime both to dynastic China and the ‘bourgeois revolution’ of 1911. As a successful modern autocracy it affirms the orthodox lineage of rulership — 正統 zhèngtǒng and 道統 dàotǒng — while betraying the original promise of fundamentally revolutionary political change with which the country’s revolutionary century began. On the opposite shore of the Taiwan Straits, the Republic of China has inherited the mantle of the Xinhai Revolution to become a constitutional democracy of a kind that was envisaged by the foes of the Qing and millennia of autocratic rule. In 2021, Taiwan poses an existential threat to Beijing. To validate the historical mandate of one-party rule under the Communists, Taiwan must be subjugated.

Dai Qing’s speech is also a corrective to Xi-era amnesia, a befuddled condition that encourages a belief that the Xi Jinping Restoration represents a radical break with the past rather than sharing an internal logic with its predecessor ‘administrations’ (in this regard, see also ‘Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’, China Heritage, 13 July 2021).

***

‘Over One Hundred Years’, of which this is a chapter, is a series of essays and translations focussed on the 2021 centenary of the Chinese Communist Party and the 110th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution. They are part of our China Heritage Annual, the theme of which is Spectres & Souls.

This chapter is divided into the following sections (click on a subheading to read):

- When Exactly Did the ‘Light Return’ 光復?

- Peace on the Edge 偏安一隅

- A Symposium on the Xinhai Revolution

- As if to Break Free of the Autocratic Gloom

- Mao Wanted the Last Word First

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 October 2021

***

The Path Less Travelled

‘We hope for an easing of cross-strait relations and will not act rashly, but there should be absolutely no illusions that the Taiwanese people will bow to pressure. We will continue to bolster our national defense and demonstrate our determination to defend ourselves in order to ensure that nobody can force Taiwan to take the path China has laid out for us. This is because the path that China has laid out offers neither a free and democratic way of life for Taiwan, nor sovereignty for our 23 million people.’

我們期待兩岸關係和緩,我們不會冒進,但絕對不要認為台灣人民會在壓力下屈服。我們會持續充實國防,展現自我防衛的決心,確保沒有人能逼迫我們走向中國所設定的路徑。因為中國所設定的路徑裡頭,不會有台灣民主自由的生活方式,更不會有兩千三百萬人的主權。

— Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文, 10 October 2021

***

Tsai Ing-wen & Xi Jinping —

Two Leaders, Conflicting Visions

- 蔡英文, ‘共識化分歧 團結守台灣 總統發表國慶演說’, 2021年10月10日; ‘Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen’s National Day speech’, Central News Agency, 10 October 2021

- 習近平, ‘在纪念辛亥革命110周年大会上的讲话’, 2021年10月9日

Further Reading:

- Chris Buckley and Steven Lee Meyers, ‘Starting a Fire’: U.S. and China Enter Dangerous Territory over Taiwan, The New York Times, 9 October 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty’, China Heritage, 1 October 2021

- Peter Zarrow et al, ‘Light Returns 光復’, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking

- ‘1911: the Xinhai Year of Revolution 辛亥革命’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 27 (September 2011)

- Geremie Barmé, ‘Using the Past to Save the Present — Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent’, East Asian History, Issue 1 (June 1991): 141-181

***

When Exactly Did the ‘Light Return’ 光復?

October 10, 1911? January 1, 1912? February 12, 1912? March 10, 1912? When was the Republic of China founded? Did a revolutionary act create a new state de novo, a form of self-legitimating violence as the people through its representatives formed a new state? Or did the Qing create the new state through its generous abdication?

— Peter Zarrow, After Empire: The Conceptual Transformation of the Chinese State, 1885-1924, 2012, p.213

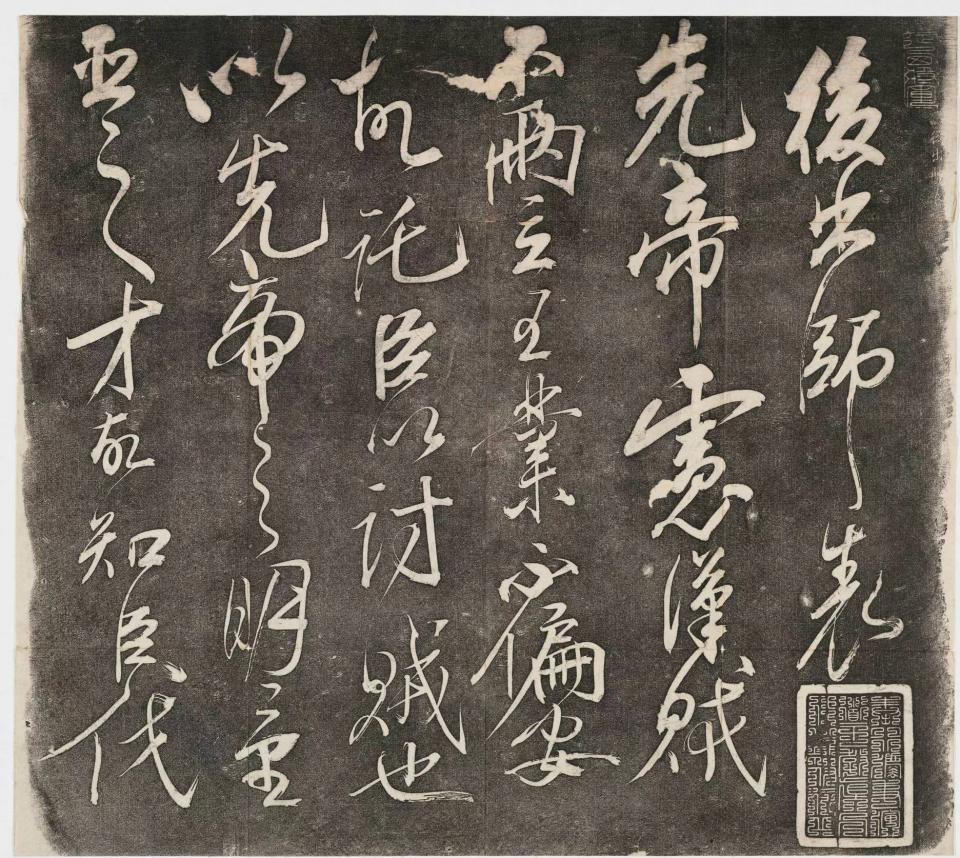

Setting the Tone for the Great Revival of the China Race

‘Often in history has our noble Chinese race been enslaved by petty frontier barbarians from the North. Never have such glorious triumphs been won over them as Your Majesty achieved. But your descendants were degenerate and failed to carry on your glorious heritage … … 蓋中夏見制於邊境小夷數矣,其驅除光復之勳,未有能及太祖之偉碩者也。後世子孫不肖,不能敪厥武 … …

‘The Tartar savages were able to take advantage of the presence of rebels to invade and possess themselves of your sacred capital. From a bad eminence of glory basely won, they lorded it over this most holy soil, and our beloved China’s rivers and hills were defiled by their corrupting touch, while the people fell victims to the headman’s axe or the avenging sword … … 因緣盜亂,入據神京。憑肆淫威,宰割赤縣,山川被其瑕穢,人民供其刀俎… …

‘Today it has at last restored the Government to the Chinese people and the five races of China may dwell together in peace and mutual trust. Let us joyfully give thanks. How could we have attained this measure of victory had not Your Majesty’s soul in heaven bestowed upon us your protecting influence? … … 北方既協,攜手歸來,虜廷震懼,莫知所為,奉茲大柄,還我漢人,皇漢民族,既壽永昌。嗚呼休哉!非我太祖在天之靈 … …

— from President Sun Yat-sen’s prayer at the tomb of Zhu Yuanzhang [founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, r.1368-1398] on 15 February 1912, published in The Times on 3 April 1912

Peace on the Edge

偏安一隅

In the Editorial Introduction to the September 2011 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, the theme of which was ‘1911: the Xinhai Year of Revolution 辛亥革命’, I wrote that:

‘Since the 1990s in particular discussions have reemerged over whether China’s century of mass revolution (geming 革命) was misbegotten, and whether the ethos of systemic rupture and radical totalizing change led to a series of historical miscalculations and disasters that favoured the ambitious and unscrupulous while doing little to realize the promise of the ideologues. In revolution’s stead gradual top-down reform (gaige 改革), essayed but unsuccessful in the late-Qing era, and renewed again from the 1970s, is seen as providing the only sustainable formula for such a complex and restive country to remain stable while essential and fundamental changes are wrought. Among some a nostalgia for empire reaffirms such timely and useful revisionism. Such waves of nostalgia are as much a result of China’s relative socio-political stability and economic reemergence as they are of commercially manufactured mass memory and local identity politics. A ‘Chinese story’ is being developed that uses a cultural and intellectual pastiche fed by various visions of greatness dating from the eras of the dynastic past, the republican period as well as people’s republic. It is a story that turns the jostling variety of China’s pasts into a modulated account; it well serves the needs of a party-state an overwhelming priority of which is to maintain stability under its tutelage.’

I also observed that:

‘The year 2011 started with [President] Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 in Taiwan lauding the Xinhai centenary for providing an occasion to celebrate democracy, modernity and social progress. On the other side of the Taiwan Strait reflections are not quite as sanguine. The previous official monopoly over the interpretation of history has long since been undermined. At least for the engaged public, the intelligentsia and the web-savvy, online forums provide unprecedented outlets for semi-public debate over the state of the country and its future. In these, as well as in the confines of more covert deliberation, the promise of the past continues to haunt the present. Despite the realities of unflagging one-party rule, groups with widely different political agendas gather, talk and plan for an uncertain future. The agendas of the brutalists, party reformers, neo-liberals, abstract social democrats, Maoists, born-again Warring States fascists (or those with views reminiscent of the war-era Zhanguoce pai 战国策派) and so on have little in common, yet they share a profound unease over the fact that the very reforms that have transformed life for countless people have also given license to egregious official behaviour. While there are those who want to see an ever stronger state willing to forswear the lure of global capital, those of a more liberal bent argue that substantive political and legal reforms are, today as in the past, urgently required to limit the party’s control over social life. For them only such changes could hope to ameliorate rising social tensions, iniquities and abuses of power in the long run. Even the top echelons of the party-state cannot ignore these discussions; all are aware that when it comes to the country’s political future, the past is not a foreign country. They know that when people speak of the political stagnation, corruption and mismanagement rife in China today they are hearing eerie echoes of another era—that of the late Qing (wan Qing 晚清).’

— 1911: the Xinhai Year of Revolution

China Heritage Quarterly, September 2011

In the New Year’s Presidential Proclamation delivered on 1 January 2011 to celebrate the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution, Ma Yingjiu had declared that the political, social and economic reforms undertaken since the 1980s had ‘thoroughly discredited the biased idea that democracy and Chinese society are incompatible’ 徹底破除了民主不適合華人社會的偏見。

Looking to the second century since the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, Ma said that as guardian of a Chinese culture that had not been subjected to the destructive politics of the Mainland, Taiwan was the global exemplar of Chinese aesthetics, creativity, moral values and a flourishing and open civil society. Furthermore, ‘We hope that all of the Children of the Yellow Emperor would, like the people of Taiwan, eventually enjoy life based on freedom, democracy and the rule of law’ 我們希望有一天,所有炎黃子孫都能和臺灣人民一樣,享有自由、民主與法治的多元生活方式。After all, Ma continued, ‘These values are not the monopoly of the West for they have been put into practice on Taiwan and I believe that, in the future, our experience should be emulated on the Chinese Mainland’ 因為這些價值在臺灣都已經實現,不是西方人的專利,臺灣經驗應可作為中國大陸未來發展的借鏡。

Commentators summed up the message of Ma’s presidential address as celebrating ‘a global China flourishing politically to one side’ 文化中華, 政治偏安。The expression 偏安 piān ān, ‘to survive peaceably to one side’, had haunted Chiang Kai-shek from the time his government retreated to the island of Taiwan in late 1949.

Over the following quarter of a century, Chiang was steadfast in his belief that the Republic of China would retake the Mainland. In the meantime, his policy was that ‘We can never co-exist with the Usurpers’ 漢賊不兩立. This was a reference to the first line of the ‘Second Memorial on Dispatching the Troops’ 後出師表 by the ancient strategist Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮, 181-234 CE) which reads:

‘The Late Emperor [Liu Bei] was of the considered view that our state and the Usurpers will never be able to coexist; a Superior Enterprise such as ours cannot be content merely to survive on limited territory.’

先帝慮,漢賊不兩立,王業不偏安。

Chiang’s rejection of the idea that his government, a ‘Superior Enterprise’ 王業 wáng yè, should content itself with ‘surviving peaceably to one side’ 偏安 piān ān also related to a history of militant defiance that dated back nearly a millennium:

‘… the Song court fled south following the Jin 金 invasion to set up a temporary capital at Hangzhou [in 1127 CE], which they renamed “Lin’an” (Lin’an 臨安), “temporary refuge”. General Yue Fei 岳飛 bristled at the suggestion that the Song had to be satisfied with an empire thus reduced and forced to “survive on limited territory” (pian’an 偏安). He derided this expression, one that dated back to the Han dynasty, but he eventually fell victim to his “patriotic” ambition to lead the Song to retake its lost northern territories. No such illusions exist for those who have used the term pian’an 偏安 in recent times.’

— from ‘The Tides of West Lake’, China Heritage Quarterly, December 2011

When, in January 2011, Ma Ying-jeou announced his vision, he was reaffirming the unique position that Taiwan had in relation to Chinese history but also within the global environment. It neatly summed up the existential and historical threat that Taiwan poses to the People’s Republic of China. For, as Ma noted in 2011, Taiwan is a validation of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution; its constitutional norms and rule of law are an affront to the centralised top-down rule of the party-state; its civil society is a rebuttal of the Communist claim that the peoples of China can only flourish under a hierarchical, repressive, one-party system that limits their basic rights and denies meaningful opportunities for political participation; while Beijing glorifies its perversion of historical knowledge, hamstrings academic inquiry and public debate corrupting thereby the minds and befuddling the souls of both the complicit and the servile, Taiwan nurtures ‘independent minds and free spirits’ 獨立之精神 自由之思想; furthermore, its global perspective is a daily provocation to the xenophobic rabble on the Mainland.

As the Republic of China / Taiwan celebrated the 110th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution on 10 October 2021, the ancient expression 漢賊不兩立, ‘we will never be able to coexist’, had a new resonance, both for Taiwan and for those countries that support its democracy against the pressing threat of Beijing domination.

On 10 October 2021, Tsai Ing-wen articulated the old expression by means of a new and provocative formulation. Declaring that neither the Republic of China nor the People’s Republic ‘should be subordinate to each other’ 互不隸屬 Tsai announced ‘Four Commitments’ 四個堅持:

‘Let us here renew with one another our enduring commitment to a free and democratic constitutional system, our commitment that the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China should not be subordinate to each other, our commitment to resist annexation or encroachment upon our sovereignty, and our commitment that the future of the Republic of China (Taiwan) must be decided in accordance with the will of the Taiwanese people.

‘These four commitments are the bottom line and common denominator that the people of Taiwan have given us. On the basis of this shared foundation, we have a responsibility to seek an even broader consensus, so that we can be united in the face of future challenges. We all share the responsibility to ensure that the young people and future generations of this land can continue to live free.’

所以,我們必須彼此約定,永遠要堅持自由民主的憲政體制,堅持中華民國與中華人民共和國互不隸屬,堅持主權不容侵犯併吞,堅持中華民國台灣的前途,必須要遵循全體台灣人民的意志。

這四個堅持,是台灣人民給我們的底線,也是我們最大的公約數,站在公約數的共同基礎之上,我們有責任累積更多的共識,以團結的姿態,來面對未來的挑戰。

我們身上有一個共同的責任,要確保這塊土地上的年輕人,可以世世代代,繼續自由奔放下去。

— Tsai Ing-wen, ‘Forging a stronger consensus: Standing united to protect Taiwan’, 10 October 2021

Unsurprisingly, Beijing’s response was fast and furious and a spokesman for the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council denounced Tsai for:

‘Trumpeting “Taiwan independence”, encouraging division, perverting history and distorting the facts. So-called “consensus and unity” are nothing but a sham formulated to hijack popular opinion and collaborate with foreign forces in a provocative move to an “independence gambit”.’

這篇「講話」鼓吹「台獨」、煽動對立,割裂歷史、扭曲事實,以所謂「共識、團結」為幌子圖謀綁架台灣民意,勾連外部勢力,為其謀「獨」挑釁張目。

***

In the memorial that he composed in 228 CE urging his ruler to go to war, Zhuge Liang also offered a warning:

‘No one can predict how things will unfold. … Events are unpredictable. Nonetheless, I shall bend my energies to the task until I can do no more; I will persist until my last breath. However, I do not have the gift of foresight and there is no knowing what the future holds: be it a smooth progress or an arduous journey, and whether we will be successful or not.’

夫難平者事也。… 凡事如是,難可逆見。臣鞠躬盡力,死而後已;至於成敗利鈍,非臣之明所能逆睹也。

In 1276, Mongol forces captured the Southern Song capital of Lin’an (Hangzhou) and in 1279 they defeated what was left of the Song army at the Battle of Yamen.

***

Introducing a Symposium on

The Forgotten Xinhai Revolution

San Francisco, March 2011

The ‘Symposium on Historical Figures of the Xinhai Revolution’ was held on 26-27 March 2011 in one of the main cities where Sun Yat-sen and his comrades raised funds to support what would eventually be an epoch-making uprising. Over one hundred scholars and specialists gathered to re-examine that history, discuss and analyse the stories of leading figures of the Xinhai Uprising whose histories have been distorted in or eliminated from the public record. Chen Kuide (陳奎德, 1946-) of the Princeton China Initiative and chair organiser of the event described the gathering in the following way:

‘Sixty years of the past century have been a vast wasteland. The achievements of far too many outstanding individuals were submerged in the torrent of events leaving mere flotsam and jetsam in their wake. It is a pressing duty therefore to recuperate that lost history and to construct a truthful narrative. No longer can we as survivors avoid our responsibility; we must elucidate the stories of those hidden spectres for they are powerless to claim their rightful place in history.

這100多年,同時也是大洪荒時期,特別是後面的60年,眾多的卓絕風華的人物,在滔滔的洪荒中被吞沒了,剩下了一些垃圾在洪水上面飄蕩。這就給我們提出一個搶救歷史和重建歷史的任務,我們無法回避幸存者的責任,我們必須去彰顯那些逝去的精靈,因為他們已經不能為自己伸張正義了。

Dai Qing travelled to San Francisco to attend the symposium and delivered the opening address (see below) in which, among other things, she noted that despite their different perspectives participants shared ‘a determination to free ourselves from the gloom of autocracy and greet a dawn of intellectual and spiritual independence.’ 起码有一点是共同的:冲出专制统治的黑暗,迎接精神自由的黎明。

— from C.K., ‘臧啓芳追思研討會在舊金山舉行’, 《自由亞洲電台》2011年2月28日

The symposium was also a commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Chang Chi-fang (臧啟芳, 1893-1961) who, among other things, had been an editor of Counterattack Magazine《反攻》on Taiwan. Returning to China in 1923 having completed his studies in America, Chang had a career as a professor of economics, university administrator, editor and government official. Apart from his prominent role in the Three Principles Youth Core of the Nationalist Party, members of which were later rigorously persecuted by the post-1949 Communist government, Chang is known as a translator of The American Municipal Government. His granddaughter, Ramona Sheng (盛雪, aka 臧錫紅, 1962-), a journalist and democracy activist based in Canada, was one of the moving forces behind the symposium.

***

Related Material:

- 萬毅忠, ‘追尋逝去的民族魂——籌辦辛亥百年風雲人物紀念活動側記’, 《萬毅忠的博客》, 2010年12月1日

- 盛雪, ‘千古啓芳 傲立蒼茫——《千古人傳頌》前言’, 《縱覽中國》, 2011年11月11日

As if to Break Free of the Autocratic Gloom

走出專制統治黑暗

Dai Qing 戴晴

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Opening address at the Symposium on Historical Figures of the Xinhai Revolution and the

Memorial Meeting to Commemorate Chang Chi-fang, 26 February 2011, San Francisco

《辛亥百年風雲人物學術研討會暨先賢臧啟芳追思會》開幕辭

The following speech is a lament as well as being a reaffirmation of its author’s unwavering belief in individual and collective acts of resistance. However, even as others were swept up in what I call the ‘China hopioid crisis’ of the first decade of the new millennium, Dai Qing remained scathing in her assessment of China’s ‘rise’.

The concerted efforts of independent actors, businesses and groups, be they in journalism, the arts or academia, seemed for a time to be bolstered by promising changes in the Chinese publishing and intellectual worlds at the time. The state publishing industry in particular had, as recently as January 2010, announced significant reforms in publishing that recognised and encouraged new possibilities for non-state enterprises. This translation of Dai Qing’s March 2011 speech is, by contrast, appearing just as new bans on non-state funds/ capital (i.e. businesses) involved in news-related activities were announced.

Restrictions on independent or non-conforming ideas and information were a key aspect of the Xi Jinping Restoration even before his rise to power in 2012; in the years since the internal announcement of bans on academic freedom in April 2013 they have only accelerated.

Stifling limits on China’s intellectual, cultural and social life will likely persist during the reign of Xi Jinping, even as a myriad of actors work to undermine them. As was the case of Mao-era obscurantism, however, they will likely prove to be co-terminus with their author’s pusillanimous existence.

— The Editor

***

***

In the century that has passed since the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 undertook to ‘bury imperial politics’, China remains incapable of freeing itself from the caliginous spectre of autocracy and totalitarianism.

從「埋葬帝制」的辛亥革命到今天,一百年過去——中國還沒有走出專制極權統治的黑暗。

For me this tenebrous presence has appeared in various guises, including:

- Engineered political repression. Starting with the political movements launched in the early 1950s — such as, ‘the suppression of reactionaries’ and the ‘elimination of counter-revolutionaries’, as well as the nationwide imposition of a ‘class classification system’ — this has continued up to the present day when critics of the system are silenced on spurious charges of sedition; and,

- Economic exploitation by the state. This began with the land reforms of the late 1940s and early 1950s; it continued during the ‘socialist transformation of capitalist industries and enterprises’ [from 1953 to 1956]; proceeded as part of the rural communisation movement of the Great Leap Forward era [in the late 1950s]; and, it continues in the guise of state-imposed rules and regulations governing the rental of private housing and extends to the present-day encroachment of the state on private business, not to mention the state’s monopoly practices and the predatory fiscal policies governing agricultural land.

Even more relevant to my point, however, is what I regard as China’s self-imposed civilisational darkness, in particular the country’s ‘manufactured ignorance’, that is, the state-sponsored beclouding of understanding and the despoliation of education. These both serve to aid and abet the asphyxiation of the spirit.

The country’s leaders willfully and knowingly engaging in policies aimed at national nescience and sciolism. This enterprise is engineered in such as way as to make it impossible for the Chinese to understand their history and the historical figures who have played an essential role in it.

這裡所說黑暗,除了政治壓迫(建政初期的「鎮反、肅反」、「階級成分劃分」……到今天的「意圖顛覆國家罪」)、經濟盤剝(從建政初期的土改、「資本主義工商改造」、人民公社化、城市私房出租規定……直到今天的國進民退、行業壟斷、土地財政),在今天的會上,這「黑暗」,特別指「文明的黑暗」,指「認知的黑暗」,指「教育剝奪和精神窒息」,指在政客的暗算下,蓄意製造的全民性蒙昧——對本民族歷史,對活躍其間歷史人物。

It is remarkable that in an era that has witnessed an explosion of all kinds of media and means of communication China’s government has chosen to employ a claque of unproductive and obscurantist hacks who are devoted to keeping the country and its vast population in the dark.

One marvels at the tenacity and inventiveness of the power holders and, for that matter, at the complicity of those over whom they rule, that is, the Chinese people themselves who perversely take pride in their self-serving accommodation with the status quo. In their mute compliance and twisted view of ‘common sense’ they are co-creators of a ‘modern political discipline’ which has led to a society wide lack of tolerance, let alone respect, for different opinions. It rejects the idea of a public sphere in which people broadly agree on the rules of engagement yet fosters rather an unwillingness to engage in the art of compromise … .

Integral to the tireless pursuit of self-legitimation, China’s rulers have developed a well-honed talent for bowdlerising and repackaging history. Since they enjoy a monopoly over the country’s assets, as well as political power, they are in an unrivaled position to devote as many resources as necessary to achieving their purpose.

在人類知性活動、特別傳播手段爆發的20世紀與21世紀,一個國家、一屆政府,依仗一批不事生產的文痞,依舊得以在如此廣泛的人群與如此長的時段維持黑暗,權柄執掌者的手腕固然曠古少有,更重要的,是被統治者的機巧、麻木、馴順、常識欠缺與「現代政治訓練」不足——對不同意見的容忍與尊重;對共同規定的遵守;懂得並且實踐妥協……。

為標榜其統治的合法性,當局打出相當奏效的一手:篡改並且重新包裝歷史——以絕對不容挑戰的公權力、以它掌控的全部資源。

It was back in the early 1980s that I happened upon a slim volume that, on the surface, shouldn’t have been of any interest. The Order of Battle of the Chinese Army During the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance was compiled and published by the Museum of History in Beijing. Only when I read it did I realise that, despite everything we had been taught, China’s eight-year-long sacred war with Japan [of 1937-1945] could not possibly have been led by the Chinese Communist Party.

[Note: See, for example, 1937年國民革命軍戰鬥序列.]

The armies and campaigns that we had been taught about — including accounts of the campaigns of the Eighth Route Army, the New Fourth Army, the victory at Pingxing Guan and tunnel warfare — were, in fact, only a minuscule part of a vast theatre of military operations under the command of the National Army [of the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek], which far outnumbered the Communist forces. In fact, the National Army persecuted military campaigns that were far more important, more noble and far bloodier [than those we knew about]. The efforts of the National Army that was so much larger than that of the Communists were the crucial factor in protecting the nation.

The National Revolutionary Army — not counting the air force or the various ground forces engaged on Burma, India or the far northwest — consisted of forty field armies. The much-vaunted Eighteenth Field Army under the command of Zhu De and Peng Dehuai was merely one of forty! Then there are the absurdly distorted accounts of the ‘Victory at Pingxingguan’ [although heavily promoted by the Communists, it was little more than a minor battle involving minimal losses on both the side of the Communist forces and the Japanese. The Reds captured 100 trucks full of supplies and they promoted the victory as a major achievement although it was the only division-size battle they fought during the entire war]. As for the celebrated role played by Lin Biao’s forces during the melée, they were little more than logistical backup that played a minor role after the Communist army had ambushed the Japanese [a tactic crucially supported from the air by the Nationalists].

At the time [I read that booklet] I had already passed ‘the age of confusion’ [as Confucius put it; that is, over forty years old. Dai Qing was born in 1941]. Moreover, I had reached my forties without ever having suffered political persecution and I had never gone hungry. I was completely educated by and within our system. Yet, here I was, completely ‘confused’ by what proved to be basic historical facts.

[Note: Dai Qing’s shock at learning about the actual role of the National Army was all the more profound because she had grown up with the family of Ye Jianying (葉劍英, 1897-1986), a military leader in the Communist Party who, along with Zhou Enlai, had been a senior Communist liaison officer who worked closely with the National government during the war]

Since China has long instituted policies of open-door economic reform, added to by the impact on the everyday lives of normal people of online culture, more fact-based accounts of past events, more believable depictions of historical figures should by all rights be appearing in dedicated publications, in the mainstream media, in online forums and in popular discussions and debate. Tragically, however, political repression is ever present and the lure of money overshadows everything, so much so that the Chinese who ‘have no need to fret over their basic livelihood’, there is an unspoken consensus that it’s best if you keep your mouth shut. Mindless spoofs of historical events produced for mass media consumption are the preferred fodder of the masses, including on such public platforms as the radio, TV, in commercial books and in school texts … … all weapons in the armory deployed by the rulers to maintain their political dominance.

我本人直到1980年代初,才在一個偶然機會下,看到一本毫無「趣味性」可言的、薄薄的史料編纂:歷史博物館出版的《抗日戰爭時期中國軍隊的作戰序列》。

我第一次知道,原來八年民族聖戰,根本沒有可能如歷來被教導那樣,是共產黨領導的;我第一次知道,原來除了八路軍、新四軍、平型關大捷、地道戰地雷戰之外,還有別的中國軍隊;還有各個戰區和其他路軍;還有更大規模、更加慘烈與驚天地泣鬼神的保國守土。

「國民革命軍」,不說空軍,以及諸如「中國入緬遠徵軍」、「中國駐印軍」、傅作義指揮下的「綏西抗日部隊」等陸軍,單單冠以「集團軍」稱號的,就40個,而朱德、彭德懷任正副總指揮的第18集團軍,不過其中之一。當然,還有那個破綻百出竟無人嚴正點破的「平型關大捷」:投入八個軍的平型關戰役,林彪115師所擔負的,僅是在喬溝伏擊日軍後勤補給隊。

那年,我已過「不惑」,而且是在屬於既沒有受到政治壓迫,也沒有餓飯,即在所謂「受足基本教育」之下進入「不惑」的。然而,就基本歷史常識而言,「惑」到如此地步。

當然,今天,由於中國已經對外部世界開放,更由於網絡已經無可阻擋地滲入普通百姓的日常生活,真實的歷史場面、生動可信的歷史人物,本應越來越多地出現在專著、傳媒、博文和眾人的議論中,可悲的是,政治壓迫無所不在;金錢誘惑如影隨形,在已然「衣食無虞」的中國人裡邊,緘口變成共識,戲說變成受眾的自主選擇,更何況本屬於公共資源的廣播電視、報刊書籍、教科書……仍被執政黨視為「坐天下」利器。

Today, in this great power that is ‘rising in global prominence’ — a ginormous, corruptly indulgent cesspit of a place — to walk free of the stygian gloom of ignorance and strip the politicians of their deceptive camouflage — regardless of whether those disguises are grandly carved in marble or printed in lavish volumes with gold lettering on their covers — there are those who would doggedly pursue the truth, who would work to unearth those buried historical truths, for in China today, there are any number of feeble serpentine streams flowing and in their discreet fashion they describe a course through the vast desiccated earth despite all of the garbage that would distract.

There is no way of knowing at present which of those streams will end up drying up; nobody is paying attention to which feed off themselves, and just happen to find a course through stands of trees and over tracts of grassland. There is no way of knowing when or how they will be joined by their fellows and how those disparate bubbling streams may course through the mountains and valleys flooding towards the open plains to become a vast torrent which will bring with it the awakening of an entire nation.

The true revival of China will not be marked by a landing on the moon, or by some claim that the nation’s GDP is the second largest in the world. Nor will it be signified by smiling handshakes at the White House. China’s true advent as a modern nation will only become a reality when the Chinese can finally discard ignorance and cast aside the enveloping darkness.

The renaissance of a culture is like a mighty torrent — will we live long enough to see it, I wonder? Can you imagine it: after millennia of authoritarianism a China with truly independent media; publishers who can decide for themselves what they can and will publish; schools that are free to set their own curricula and select their own text books … …

When that day finally comes there will be lecture halls in which people can engage in free and open discussion; films that touch the soul and are truly part of an international culture, rather than works that reflect an insipid imaginary peopled by concubines to murderers.

On that day, China will be able to boast of pianists who can do more than simply play the right keys…. … Korean War that the boss behind it all was going to be the hegemon of Asia and the leader of the Third World. They’ll know about the countless loyal patriots who were eliminated during the movement to ‘suppress counter-revolutionaries’ [from 1950 to 1953 during which an estimated 1 to 5 million people were eliminated]… … Okay, even if people don’t learn about any of that, in primary school they should have been taught that ‘green means go and red means stop’; they should at least know how to behave in diplomatic settings and that, even though they might feel self-important for a time, in reality their bluster is but a thin disguise for the sense of impotence they secretly feel.

在今天這個龐然、奢靡、渾渾噩噩地撈世界的「崛起」大國,走出蒙昧暗夜,撕去政客偽飾——無論雕在花崗岩上還是印在燙金文集里——堅持理性探索,發掘歷史真實,在中國,像條條細弱的涓流,正幽幽地蜿蜒在紙醉金迷下的荒漠國土。沒有誰知道哪一條小溪怎麼艱難地流,怎麼默默地乾涸;沒有誰在乎它們以自己生命滋潤的,不過是偶然流經的幾株樹木、幾片草灘;沒有誰知道,要到哪一天才能大家能呼朋引類——潺潺的泉流匯成小溪,衝出山谷、流向原野,匯成民族覺醒的大河。中國的崛起,不在登月、不在GDP老二、不在白宮的微笑握手,只在國民走出蒙昧與黑暗。

文化復興的奔湧啊——我們還能活到那一天麼:歷經千年專制的中國,傳媒得以獨立播出,出版社能自己決定出版計劃,學校終於能自主選擇教科書……我們終於有可以自由討論的講堂,有了與世界溝通的心靈震撼的電影,而不是如今天這樣,除了妾婦奴才就是喊打喊殺;我們的鋼琴家也不再只能熟練地敲鍵盤,而知道冷戰中的強權如何火中取栗、知道志願軍出境作戰,不過因為操縱他們命運的人得到老闆首肯要做亞洲和第三世界領袖、知道傷及無數忠忱愛國之士的「鎮壓反革命」如何終於有了立即推進的名目……就算這些都不知道,也應該通過一個國家最最基本的初小教育,知道「紅燈停綠燈行」;知道外交場合小動作,雖得意於一時,反映的其實是內心虛弱。

Starting with that booklet I began to search out people and to interrogate history for myself — not merely to satisfy a momentary curiosity but rather because I could not bear to live any longer in the fog of ignorance. If, as the authorities presumed, you could be satiated by what the government fed you, then you’d certainly be happy enough to applaud moronically the dreck that was served up by CCTV, like the Spring Festival Extravaganza. … But that would be no better than to live a life of shame.

There were countless young people like me, as well as the not-so young — thousands, tens of thousands, no, millions if not hundreds of millions, of fellow Chinese who were not satisfied with being merely the ‘useful tools’ [of the party-state], living out their lives as little more than mindless zombies. We are the custodians of Chinese culture in the information age, one in which there are not many opportunities left [to record the past]. And so, we take upon ourselves the task to make an effort, one step at a time, to break free of the party committees in our schools and the propaganda departments. We have used our own resources — such as taking heed of the stories told to us by our grandparents; collecting memorabilia and antiques; by using our own eyes and relying on our own hearts; employing our sense of belonging and responsibility to the land of our birth — to re-examine history itself.

It is over thirty years now since I held that little booklet as I sat on the steps of the History Museum on the eastern flank of Tiananmen Square. I recall the sense of being completely dumbstruck as I looked through those lines of unadorned statistics.

How often over the years have people tried to break through the ideological obduracy that suffocates China? Think of all the blood, sweat and tears!

從那本小冊子起步,我開始尋訪前人、叩問歷史——不為滿足一時的好奇心,只為不甘生活在蒙昧之中。如果如當局所說,政府把你餵飽了,就該樂呵呵地在滿是垃圾的央視春晚上拍巴掌……無異於做人的恥辱。想來和我一樣,成百上千、成千上萬、上十萬百萬千萬,乃至上億的不甘為「工具」、不甘為行屍走肉的年輕和不再年輕的同胞——我們中華文明在信息時代所剩機會不多的傳承人——正以自己一步復一步的努力,擺脫校黨委、中宣部;以自己的資源,比方說,祖父講的故事;比方說,一點一滴的文物收藏;以自己的眼光、心胸;以自己對吾國吾土的責任,重新審度歷史。

我至今記得,當時怎麼手握小冊子,怔怔地坐在天安門東側廣場歷史博物館台階上;記得怎麼在一行行簡單的數字面前歷經的震撼——那已經是近乎30年前的事了。30年過去,在這片板結的土地上,我們掘下幾鎬?撒下幾滴血汗?

Today, we are gathered here as a result of the generosity of the Chang family and, over the following two days, we will at this hard-to-come-by place, learn about the profoundly moving and dramatic stories involved in the Xinhai Revolution and the development of modern China, stories related and analyzed. We will appreciate anew the extraordinary amounts of effort that people made and how significant the sacrifices… We will travel through space and time to visit our ancestors, not only as part of our quest to affirm our own sense of a spiritual civilization — after all, how many of those present have the blood of Xinhai revolutionaries coursing through your veins. How many of you are the genetic descendants of that generation?

- Over the next two days, we will revisit the military rebellion that later generations would hail as a ‘revolution’;

- The speakers will tell us about the efforts devoted to drawing up the Provisional Constitution of 1912 and the struggles over revisions to that document and how the groundwork for meaningful elections, that most basic act of modern political life, also involved the struggle by women who demand the right of political participation; [Note: Women did not get the vote until 1947, shortly before the Communist takeover in 1949. See Ono Kazuko, Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, 1988]

- The speakers will tell us about the efforts of [the human rights activist and social democrat] Carson Chang [張君勱, 1886-1969] and discuss whether academics should become involved in politics. By discussing the lives of the jurist Zhang Yaozeng [張耀曾, 1885-1938] and the lawyer Li Zhaofu [李肇甫, 1887-1851, who starved himself to death in protest at his arrest by the Communists] — both senior ‘republican bureaucrats’ — we will better appreciate their frustrations; we will learn about their unblemished and frugal lives and understand how different were their values and morals from later leaders who claimed that they were ‘serving the people’; [Note: For a discussion of other Republican-era luminaries — Wang Ch’ung-hui 王寵惠, John Ching Hsiung Wu 吳經熊, Chao Lung Yang 楊兆龍, Ken-sheng Chou 周鯁生, Wang Shih-chieh 王世傑, Tuan-Sheng Ch’ien 錢端升 and Li Hao-p’ei 李浩培 — see Gong Renren 龔刃韌, ‘How the Humanities and Social Sciences Are Holding China Back’, China Heritage, 28 June 2019; and, Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘I Will Not Submit, I Will Not Be Cowed’, China Heritage, 10 October 2019]

- The speakers will base their remarks on their personal experience and share with us the view that the ‘great traitor’ described in textbooks was in fact an unassuming and moderate individual loyal to his country. And we will encounter the greatest unsolved case in China today — that of the village head Qian Yunhui [錢雲會] — and the local worthies of his village who, for the past century, have made sacrifices for a cause greater than themselves.

今天,難卻臧家盛情,我們聚集到這裡。在接下來的兩天,將在這個極為難得的場合,通過一個個故事展現和分析,知道由辛亥而開啓的現代中國,曾經有過多少驚心動魄的奮鬥,曾經有過多少契而不捨的努力,曾經有過多少壯烈的犧牲……我們跨越時空、追訪先賢,不僅為找尋已成社會公器的精神文明——在座者,你們多少人是辛亥先賢血脈、基因直接承繼人啊!

兩天的會議,將把我們帶回到百年前因為「兵變」——或者後世通稱的「革命」——而開啓的那段日子;

演講者將告訴我們,在對《臨時約法》的修訂乃至抗議中,「選舉」這一民主政治最基本生長點,怎麼在婦女平權上閃亮;

演講者將透過張君勱的奮發與頓挫,探討學者到底該不該從政;透過張耀曾、李肇甫這樣「民國高官」如何忠忱為國而「求不得」;透過他們潔淨、清貧的生活,看出與「為人民服務」之領導決然有別的宗旨德行;

演講者將以自己的切身經歷告訴我們,教科書上的「第一大奸」,如何平樸、謙和、公忠體國;還有而今中國第一重大疑案——浙江樂清民選村長錢雲會——的前輩鄉賢,百年以來不曾間斷的壯烈與忠勇。

And then there is Mr Chang Chi-fang, a man who passed away half a century ago but whose life was the inspiration for this gathering .

The speakers will present unpublished work about the life and activities of Professor Chang — academic, mayor, government supervisor, university president. A man who, regardless of the duties that he took upon himself, was a model of consistence, wisdom in practice and responsibility. When, having been forced to ‘find peace on the edge’ [偏居一隅, a reference to 偏安一隅, see ‘Peace on the Edge’ above], the economist and expert on government finances Chang Chi-fang devoted his energies to the magazine Counter-offensive for the last ten years of his life.

‘Counter-offensive!’ — the very word used to send shivers of terror through us, for it conveyed a sense of hate and fearful doubt. How could such a word be compatible with a man who had been the president of Northeastern University during the war years when it relocated to West China? How does it relate to the violent decade of the 1920s, or the encirclement campaigns and aerial bombing [of the Communists] in the 1930s? Let alone the blood-soaked war years of the 1940s… … Over the two days of this symposium scholars will tell us how Chang Chi-fang maintained his ‘counter-offensive’, a resolute stance that in fact reflected love for his nation, its people and his family; a resolute stance born of his clear-headed critique of Leninism, an ideology that perverted ideals in the service of its political program and his fervent wish to ‘regain the lost mountains and rivers’ 從頭收拾舊山河 [of China].

[Note: ‘從頭收拾舊山河’ is the last line in a famous ci-lyric poem attributed to Yue Fei (岳飛, 1103-1142), the celebrated ‘loyal general’ of the Southern Song dynasty who was killed by pacifist politicians opposed to his bellicosity. Yue Fei is China’s model ‘patriot’]

更有本次研討會之磨心,五十年前離世的臧啓芳先生。

演講者將以他們尚未發表的一手資料,給出離亂與動蕩之中,非高官、遠豪門,僅以自己的學識膽略,接受國家委任的臧教授、臧市長、臧督察、臧校長,如何在一個又一個崗位上表現出的堅韌、智睿與責任;而到隔海偏居一隅之際,這位經濟與財政專門家,慨然主政《反攻》雜誌十年。「反攻」!這個曾讓我們驚怵不已、並且傳遞著仇恨、疑懼的「反攻」,如何與西遷東北大學校長切合?二十年代的濺血拼殺麼?三十年代的飛機大炮剿滅?更遑論四十年代沃野千里的隆隆戰火……在這兩天的會里,研究者將告訴我們,臧啓芳堅持「反攻」——飽含著對國土、百姓,乃至他親生骨血的摯愛,飽含對邪惡的洞悉、對偷盜理想之列寧主義的清醒批判,飽含著「從頭收拾舊山河」的堅定渴想。

On the mainland internet at the moment a hot topic of discussion is the fact that the painting ‘Valour Lives On’ [ 浩氣長流, which depicts anti Japanese war heroes of the National government and army long vilified and ignored by the Communist Party’s court historians] has been exhibited on Taiwan. This 100-metre-long work which took eight years to make is concrete evidence that the most valid way to discuss the ‘Sacred War of the Nation’ is best determined by those thinkers, artists and activists who retain grassroots independence. Such acts of representation belong to all Chinese people and not merely the power-holders who control archival materials.

The spirit that informs our symposium is the same as that which motivated the efforts of Wang Kang [王康, 1949-2020] and the other artists who created ‘Valour Lives On’. Although different they employ a shared language. This is the first time in many years that a single family and a small group of devoted grassroots activists have been able to take the lead like you here today. You have come together from different professional backgrounds, from different perspectives, and different strategies, as well as different value systems, to reveal, explain and discuss events despite whatever our differences may be. Who is to say that an endeavour like this might not provide a practical model for others who wish to engage in historical investigations not bound by officialdom?

The ‘Century of Xinhai’ has been subject to political persecution and willful ignorance, not to mention premeditated attempts to banish altogether. Such efforts if successful would result in an irreparable loss to the Chinese nation.

[Note: See Rana Mitter, China’s War With Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival, 2013]

今天在大陸,網上正熱傳台灣首展的「浩氣長流」。這幅費時八年、長八百米的長卷告訴我們,對「民族聖戰」表達,屬於堅守民間立場的思想家、畫家、活動家;屬於全體中國人,而非手握資源的當局。我們的「辛亥百年風雲人物學術研討」,和王康他們在精神與原理上遙相呼應。多少年來,第一次,一個家族與一小批民間志士走在了前頭。他們集合起不同專業、不同視角、不同方略認同、甚至不同價值取向的各路人馬,揭示解說、撞擊切磋。誰能說,這一努力,不會開啓一個民間問史的可行模式?

「辛亥百年」精神財富所遭遇的或無知、或居心叵測棄置,是中華民族最大損失。

We have come together today to investigate an historical gold mine. Our approach and our understanding may well differ, but we share one thing in common: a determination to free ourselves from the gloom of autocracy and greet a dawn of intellectual and spiritual independence.

My thanks to the Chang family; my thanks to all of you worthy men and women here today; and my best wishes to you all for the success of this symposium.

我們今天走在一起,發掘這座金礦——可能有不同的見解包括立場,但起碼在一點上是共同的:衝出專制統治黑暗,迎接精神自由的黎明。

謝謝臧家。謝謝諸位志士。祝會議成功。

***

Source:

- 戴晴, ‘走出专制统治黑暗――《辛亥百年風雲人物學術研討會暨先賢臧啟芳追思會》开幕辞’, 《新世紀》, 2011年10月3日

‘In his final years, Sun Yat-sen was nothing more than a Soviet-Russian puppet; he was completely under their thumb.’

孫文晚年已整個做了蘇俄傀儡,沒有絲毫自由。

— Liang Qichao 梁启超 writing to his daughter, 5 May 1927

***

***

Mao Wanted the Last Word First

Let us pay tribute to our great revolutionary forerunner, Dr. Sun Yat-sen!

We pay tribute to him for the intense struggle he waged in the preparatory period of our democratic revolution against the Chinese reformists, taking the clear-cut stand of a Chinese revolutionary democrat. In this struggle he was the standard-bearer of China’s revolutionary democrats.

We pay tribute to him for the signal contribution he made in the period of the Revolution of 1911 when he led the people in overthrowing the monarchy and founding the republic.

We pay tribute to him for his signal contribution in developing the new Three People’s Principles from the old Three People’s Principles in the first period of co-operation between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party.

He bequeathed to us much that is useful in the sphere of political thought.

Save for a handful of reactionaries, the people of contemporary China are all successors in the revolutionary cause to which Dr. Sun Yat-sen dedicated himself.

We have completed the democratic revolution left unfinished by Dr. Sun Yat-sen and developed it into a socialist revolution. We are now in the midst of this revolution.

It is only forty-five years since the Revolution of 1911, but the face of China has entirely changed. In another forty-five years, that is, by the year 2001, at the beginning of the 21st century, China will have undergone an even greater change. It will have become a powerful industrial socialist country. And that is as it should be. China is a land with an area of 9,600,000 square kilometres and a population of 600 million, and it ought to make a greater contribution to humanity. But for a long time in the past its contribution was far too small. For this we are regretful.

However, we should be modest — not only now, but forty-five years hence and indeed always. In international relations, the Chinese people should rid themselves of great-nation chauvinism resolutely, thoroughly, wholly and completely.

— from Mao Zedong, ‘In Commemoration of Dr Sun Yat-sen’, 12 November 1956

***