Watching China Watching

以其昏昏 使人昭昭

In 1949, the civil war on mainland China entered its final phase. The People’s Liberation Army under the command of the Communist Party was on the march to overthrow the Republic of China under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party. On 5 August 1949, the eve of the Communist victory on mainland China, the American Department of State released United States Relations With China, With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949, known simply as the China White Paper.

Mao Zedong responded to the White Paper with a series of withering, latterly ‘canonical’, essays — canonical in that these writings remain an important part of China’s foreign policy vade mecum. In an editorial published by Xinhua News Agency and in five signed articles, Mao with the help of his chief propagandist Hu Qiaomu offered a Marxist-Leninist analysis of US China policy — and for that matter China watching. The White Paper might have been an attempt at an objective review of US-China policy, but for Mao and the Communists, it was a blatant admission of US imperial designs in China, as well as a blatant admission as to the extent Washington had bankrolled the now bankrupt Nationalist cause (over the coming decades, the Communists would observe America replicating this faulty strategy when meddling with countries as diverse as Vietnam and Iraq, to name only two). These six Maoist texts are lapidary in nature: many of Mao’s observations, formulations and comments — along with particular turns of phrase and his masterful use of sarcasm — were soon embedded in China’s evolving political discourse, what I call New China Newspeak. To this day, they continue to inflect the way that the People’s Republic speaks to and about itself.

Seventy-five years after they were published, the White Paper of 1949 and Mao’s response to it remain essential reading today. Mao’s essays on the White Paper, as well as his comments in subsequent speeches and writings, bolstered the rationale for the ideological and class-based purge of universities, publishers, the media and intellectual worlds. In the early 1950s, the effect on China’s intellectual and cultural life was devastating, the darkening effect of those years is more evident than ever under Xi Jinping.

Also relevant is the seventieth anniversary of the denunciation of Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962), his advocacy of Chinese Liberalism (‘idealism’), Westernisation and humanistic scholarship, orchestrated by Mao from December 1954 to March 1955. Among the limited official reevaluations of the Maoist past, the Communists have never stepped back from the sustained nationwide attack on Hu Shi, a campaign that presaged the Anti-Rightist Purge of 1957, which was stage-managed by none other than Deng Xiaoping.

In 2024, it remains incumbent upon those who would watch China today to have retrospective clarity regarding the long shadows of the past. For more on this topic, see White Paper, Red Menace — Watching China Watching (VII), China Heritage, 17 January 2018.

***

The series Watching China Watching features essays and reflections on studying the Chinese world and approaches to understanding the Chinese People’s Republic. Our method is underpinned by New Sinology.

The men and women who taught us to engage with the Chinese world and to appreciate things Chinese in a holistic fashion were motivated and inspired by many things: their personal histories, a diverse range of interests, as well as a pressing necessity to watch (and to watch out for) China. For many of them, Chinese and non-Chinese alike (after all, some of the greatest China Watchers are from China), China was not a distant subject for study but an essential part of lived reality. Their insights were generally based not on some crude social science or anthropological approach to observing The Other, or the result of dissecting an object rich in possibility as part of some ambitious career trajectory. Their understanding was based as much on entanglement, fraught questioning, a spirit of self-discovery and personal enrichment as the result of a lifelong effort to approach what is in fact an all-encompassing cultural-political world from a broad humanistic perspective.

In this chapter of Watching China Watching, we feature China’s Thickening Information Fog — Overcoming New Challenges in Analysis by Jonah Victor, extracts of which were published by Studies in Intelligence in September 2024.

Our thanks to Jean Christopher Mittelstaedt of the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS, University of London, for alerting China Heritage to Johan Victor’s work via X/Twitter.

***

The Chinese theme of this chapter is taken from Mencius, who famously observed that:

The wise know that to enlighten others requires clarity [oneself]; today, those befuddled by the dark presume to shed light.

賢者以其昭昭,使人昭昭;今以其昏昏,使人昭昭。《孟子 · 盡心下》

The use of the word ‘miasma’ in the title is a reference to Mao’s poem ‘Reply to Comrade Kuo Mo-jo’ 七律·和郭沫若同志 ‘Inscription on a Picture Taken by Comrade Li Chin — a lu shih’ (17 November 1961), in which the Chairman warned that 妖霧又重來, the official English translation of which is ‘a miasmal mist once more rising’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

6 October 2024

***

Further Reading in Watching China Watching

- Geremie R. Barmé, The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949

- Alice L. Miller, Analysing the Chinese Leadership in an Era of Sex, Money and Power

- Robert Conquest, The Kremlin Then, Zhongnanhai Now

- Charles Parton, China Watching — old skills honed for a ‘new era’

- Kathrin Hille, China Watching in the Xi Jinping Era of Blindness and Deafness

- Geremie R. Barmé, Eating watermelon with Wu Guoguang — a summer seminar in China watching

- Wu Guoguang, Lessons from the black box of Chinese politics

- Simon Leys, Recalling an Expert ‘China Expert’

- Simon Leys, et al, Han Suyin and Two-faced People

***

China’s Thickening Information Fog

Overcoming New Challenges in Analysis

Jonah Victor

The author is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute for National Strategic Studies of the National Defense University. He has served as a senior China analyst at the Department of Defense.

Introduction

China has been a “hard target” for the Intelligence Community (IC) since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Escalating demand for assessments of China since the 2010s has spurred the IC to expand its analytical and collection efforts. Last year, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines identified China as the IC’s “unparalleled priority.”1

CIA Director William Burns asserted this year that his agency has more than doubled its budget for China-related intelligence collection, analysis, and operations during his tenure, extending work on China to “every corner of the CIA.”2 Even as the IC buckles down on China work, warning signs are emerging that the world is changing in ways that could disrupt business as usual. Washington’s ability to anticipate developments in the US-China relationship and assess risks and threats to national security is likely to get harder.

Amid heightened tensions with Washington, Beijing has redoubled efforts to stiffen controls on information to prevent access by its potential adversaries. PRC authorities are mounting increasingly conspicuous counterintelligence activities, issuing public warnings of infiltration attempts by foreign spies and restricting the use of US technology, like iPhones and Teslas, due to purported surveillance threats.3 While heightened counterintelligence will concern operational elements of the IC, intelligence analysts are likely to be most aware of the mounting, problems they face in accessing open-source information. Open source, while usually easier and cheaper to obtain than other intelligence sources, has gotten harder to gather when it comes to China.

Notably, journalists are struggling to obtain PRC entry visas, US researchers are confronted with more scrutiny and hurdles in their field work, non-governmental analysts have faced police investigations and even detentions, and their access to several essential databases has been limited by the PRC government. China specialists warn that their ability to gather and evaluate information on China is constrained by Beijing’s growing restrictions on data dissemination and international access to China.4 In 2023, historian Odd Arne Westad judged that “insights into decision making in Beijing are harder to get than they have been for 50 years.”5

These developments are alarming, but in historical context, hardly comparable to conditions 50 or more years ago. American journalist Edgar Snow, favored by Mao Zedong and granted extraordinary access to the inner circle of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), wrote in 1962:

Gaps in our information on present-day China seem limitless. The true state of China’s industrial and agricultural economy, the general standard of living, rural and urban communes and the degree to which they may have added tension to her straining efforts to catch up, developments in science, education and cultural life, how China is governed and security measures used against anti-Communist opposition, the extent of China’s military preparedness and self-sufficiency, are all in dispute abroad.”6

The IC, lacking Snow’s access inside China, did not fare much better at the time. A study of declassified National Intelligence Estimates (NIEs) on China concluded that “in the early years of the PRC, intelligence analysts enjoyed few advantages over their academic and journalistic counterparts on the inner workings of the Chinese Communist Party.”7 Neither Snow nor the IC would anticipate the economic catastrophe resulting from Mao’s Great Leap Forward.8 Storied CIA officer James Lilley recounted that his agency relied on anecdotal accounts from PRC refugees fleeing to Hong Kong and smuggled PRC newspapers to assess the deteriorating conditions in China.9

While IC and public insight into China increased after Mao’s death in 1976, former State Department analysts Batke and Melton still observed in 2017 that “we know shockingly little about the men … making decisions in Beijing.”10

The IC, of course, is chartered to delve beyond publicly available information. The open-source world, albeit vast, will rarely provide insight on state secrets such as classified war plans and weapons systems or PRC activities in cyberspace, outer space, or underwater, activities that often require technical means to detect and evaluate. But for intelligence mysteries—those abstract puzzles without a concrete answer—open-source information usually contributes the foundational evidence for assessments. These include PRC leadership intentions, economic conditions, social-political trends, and military capabilities—the essential context for evaluating national security threats.” With the executive branch, armed forces, and Congress increasingly making high-stakes decisions on China issues, the need for this information to inform public debate is greater than ever.

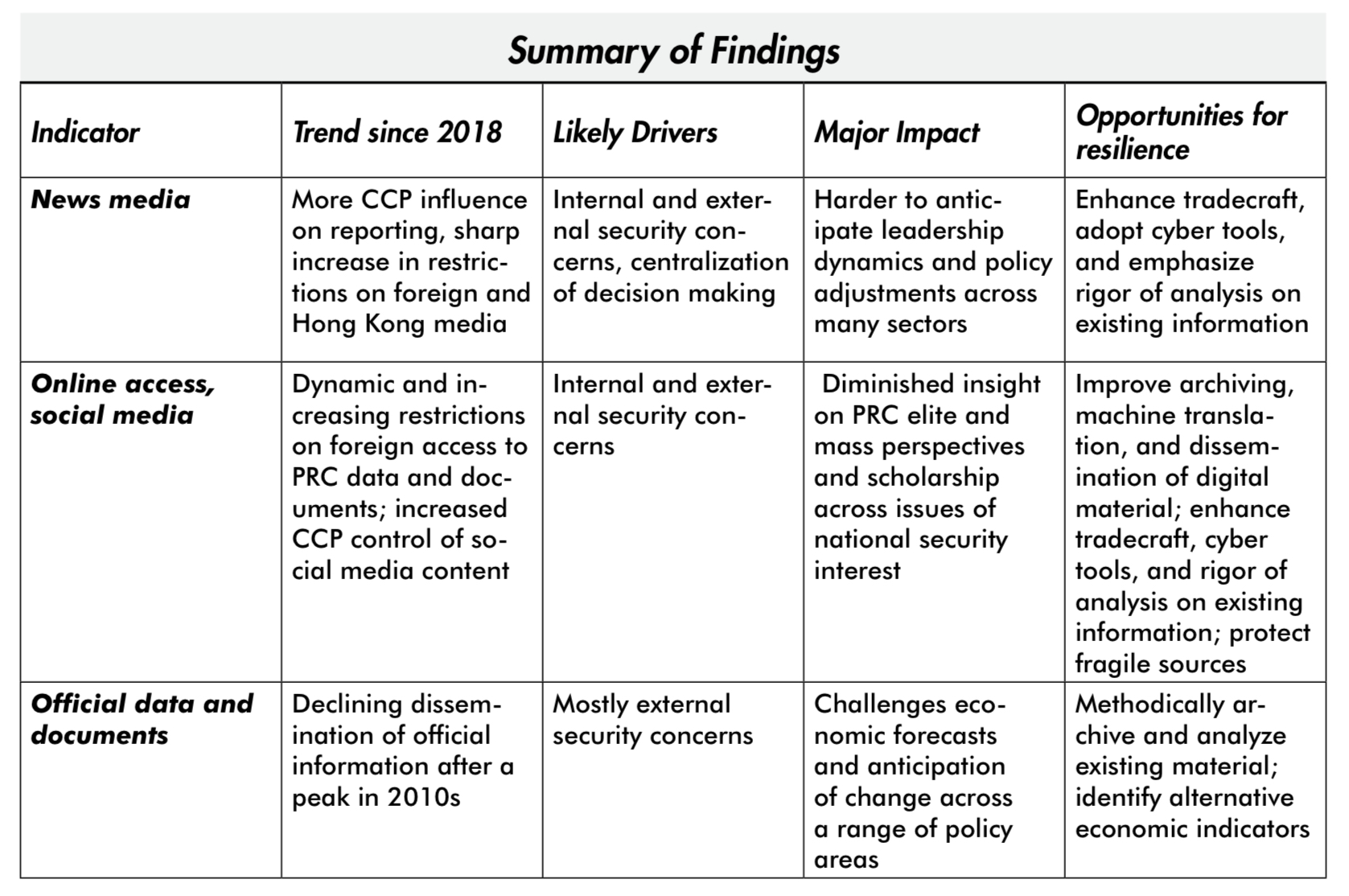

I argue here that China’s recent restrictions on open-source information are significant and likely to increase further, but near-term actions by individual analytic units and longterm efforts at the federal level could build resilience into US analytic capabilities. The following sections address:

- recent changes in information availability,

- drivers of further PRC restrictions,

- specific implications for IC analysis, and

- opportunities for analysts to thrive in changing conditions.

I interviewed specialists from federal agencies, nongovernmental organizations, news media, universities, and private sector firms. They included junior, senior, and veteran analysts with decades of experience and areas of expertise across PRC political, economic, technological, and military/security issues.

This article was informed by their experience and perspective, but it does not necessarily represent a consensus view.

***

***

Source:

- For a PDF of available material of the report, see China’s Thickening Information Fog, Studies in Intelligence 68, No. 3 (Excerpts, September 2024).

***

Notes to the Introduction:

1. Julian E. Barnes and Edward Wong, “U.S. Spy Agencies Warn of China’s Efforts to Expand Its Power.” The New York Times: March 8, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/08/us/politics/china-us-intelligence-report.html.

2. William J. Burns, “Spycraft and Statecraft.” Foreign Affairs: January 30, 2024. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/cia-spycraft-and-statecraft-william-burns. (February 22, 2024).

3. Yoko Kubota, “WSJ News Exclusive | China Bans IPhone Use for Government Officials at Work.” Wall Street Journal: September 6, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-bans-iphone-use-for-government-officials-at-work-635fe2f8; Keith Zhai, “WSJ News Exclusive | China to Restrict Tesla Use by Military and State Employees.” Wall Street Journal, March 19, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-to-restrict-tesla-usage-by-military-and-state-personnel-11616155643?mod=article_inline; “China Tells Its Citizens to Be on the Lookout for Spies,” The Economist: September 21, 2023. https://www.economist.

com/china/2023/09/21/china-tells-its-citizens-to-be-on-the-lookout-for-spies.

4. Wei Lingling, Yoko Kubota and Dan Strumpf, “China Locks Information on the Country inside a Black Box,” Wall Street Journal: 30 Apr. 2023, www.wsj.com/world/china/china-locks-information-on-the-country-inside-a-black-box-9c039928. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024; Scott Kennedy (ed.), U.S.-China Scholarly Recoupling (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2024). https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-china-scholarly-recoupling-advancing-mutual-understanding-era-intense-rivalry.

5. Odd Arne Westad, “What Does the West Really Know about Xi’s China?” Foreign Affairs: June 13, 2023. www.foreignaffairs.com/china/what-does-west-really-know-about-xis-china.

6. Edgar Snow, The Other Side of the River, Red China Today (Random House, 1962), 117.

7. National Intelligence Council, Tracking the Dragon: National Intelligence Estimates on China During the Era of Mao, 1948-1976 (National Intelligence Council, 2004). Hardcopies are no longer available. Most easily read online version is at

https://web.archive.org/web/20060619102912/http://www.dni.gov/nic/foia_china_content.html. Also available, but in individual files with no introductory material at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/collection/china-collection. U.S. Government Printing Office 2004. This specific reference to pages xii and xvi are in the introduction appearing in the web.archive.org version.

8. Ibid.

9. James R. Lilley and Jeffrey Lilley, China Hands (Public Affairs, 2009).

10. Jessica Batke and Oliver Melton, “Why Do We Keep Writing about Chinese Politics as If We Know More than We Do?” in ChinaFile: October 16, 2017. https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/viewpoint/why-do-we-keep-writing-about-chinese-politics-if-we-know-more-we-do.

11. Joseph S. Nye, “Peering into the Future.” Foreign Affairs 73 (4) (July–August 1994): 82. https://doi.org/10.2307/20046745; Peter Mattis, “How to Spy on China.” Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/how-to-spy-china-beijing-technology-mattis. April 28, 2023.

***